Abstract

Introduction

We report a rare case of an aggressive large-cell neuroendocrine lung tumour, which presented with ocular metastasis.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old lady presented with a 4-week history of left eye pain and photophobia. Ocular examination revealed left-sided episcleritis and she was treated with topical lubricants and steroids. However, she re-presented 6 months later with recurrent left eye symptoms and was found to have an iris stroma amelanotic lesion, posterior synechiae, 360-degrees rubeosis iridis, raised intraocular pressure, and trace vitreous inflammation. Ultrasound biomicroscopy revealed a left thickened iris with an associated ciliary body lesion. Sarcoid-related ocular inflammation was suspected, but a computed tomography (CT) scan of the lung revealed an incidental right upper lobe lesion. Histology from a transcorneal iris biopsy showed a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, and the diagnosis of metastatic lung large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma was confirmed via high-resolution CT scan, positron emission tomography scan, and CT-guided lung biopsy. She was given multiple courses of different chemotherapy regimens along with palliative radiotherapy. However, the tumour and its metastases continued to progress and she passed away 4 years after her initial presentation.

Conclusion

Ocular metastatic large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is rare, and the first presentation with ocular metastasis is even rarer. This case highlights the importance of early detection of ocular metastases in order to hasten oncological treatment. A low threshold for systemic investigations and ophthalmology referral in cases of unexplained, refractory ocular symptomatology is essential, given the heterogeneous presentation, rarity, and poor prognosis of these tumours, even with maximal treatment.

Keywords: Large-cell neuroendocrine tumour, Ocular metastases, Ocular oncology

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of epithelial tumours with neuroendocrine differentiation. They arise from specialized cells known as enterochromaffin (Kulchitsky) cells, which are mostly found in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, along with the thymus, parotid, breast, ovary, and testis. Due to the presence of these cells in the orbit, primary orbital NETs can occur [1]. However, most orbital or ocular NETs are metastatic from a primary elsewhere, and these are nevertheless extremely rare, with less than 40 reported cases to date as summarized by Mehta et al. [2]. We report here an even rarer case of an aggressive, fast-growing, and poorly differentiated type of neuroendocrine lung tumour, which presented with ocular metastasis. The CARE Checklist has also been completed by the authors and is attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000535233).

Case Report

A 70-year-old Afro-Caribbean lady presented with a 4-week history of left eye pain and photophobia. She had a 20-pack-year history of smoking, and she was a glaucoma suspect, with a central corneal thickness of 519 µm on the right eye and 497 µm on the left eye. On examination, she was found to have a right visual acuity (VA) of 6/4 and a left VA of 6/9, with either intraocular pressure (IOP) found to be within normal range. She was diagnosed with left-sided episcleritis and was started on preservative-free 0.2% sodium hyaluronate (Hylo-forte®) four times a day and a tailing-down regimen of preserved dexamethasone 0.1% eye drops (four times a day for 1 week, three times a day for 1 week, once daily for 1 week, and then stop). She was not given any further follow-up.

Six months later, whilst visiting family in Jamaica, she presented to a local ophthalmology unit with recurrent left eye pain and severe photophobia. In view of new iris vessels and an IOP of 32 mm Hg, she was treated for possible rubeotic glaucoma and was started on a combination eye drop of brimonidine tartrate 2 mg/mL and timolol maleate 5 mg/mL twice daily and preservative-free bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution once daily, both to the left eye. She was initially also started on acetazolamide 250 mg tablets once a day, along with a course of high-dose oral prednisolone, which was stopped after a week due to intolerable gastrointestinal side effects.

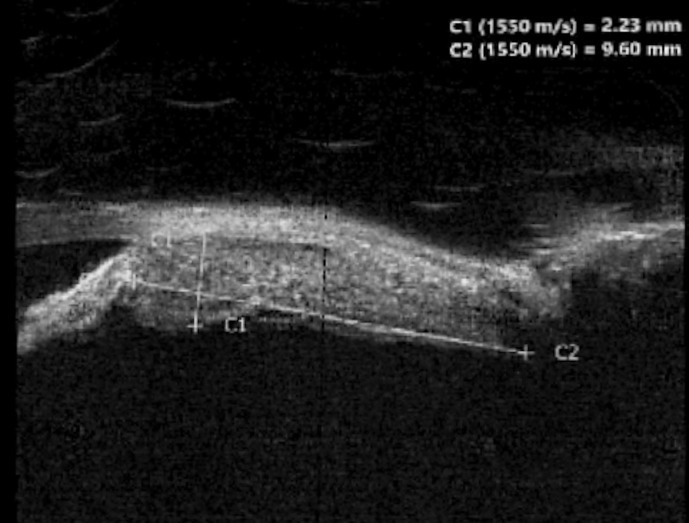

Upon arriving back in the UK 2 weeks later, she re-presented to eye casualty to check her treatment progress. Since her first visit, the left VA had dropped to 6/24 improving to 6/12 with pinhole (right VA 6/9). Clinical findings in the left eye included diffuse hyperaemia, a clear anterior chamber, an irregular iris surface with an amelanotic lesion of iris stroma between 2 and 5 o’clock, posterior synechiae, 360-degrees rubeosis iridis, and an IOP of 24 mm Hg. There were also an early nuclear sclerotic cataract and a trace of vitreous inflammation, along with a healthy optic disc. Pupils were both equal and reactive, and right ocular examination was within normal limits, with an IOP of 18 mm Hg. Ultrasound (US) biomicroscopy was done, which revealed a left thickened iris with an associated ciliary body lesion, 2.2 mm thick and 9.6 mm long, shown in Figure 1. In view of the symptomatology and the examination findings, sarcoid-related ocular inflammation was suspected, and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the lung was organized. This revealed an incidental right upper lobe lesion and she was promptly referred to the Ocular Oncology service and to the respiratory team.

Fig. 1.

US biomicroscopy showing the iris and ciliary body lesion.

A transcorneal iris biopsy was done. Histopathological examination showed a tumour composed of small round blue cells with nuclear moulding, conspicuous nucleoli, and occasional discernible cytoplasm. Immunohistochemistry was positive for anticytokeratin monoclonal antibodies AE1/AE3, with pancytoplasmic cytokeratin (CK) and CK7 staining. The tumour also exhibited focal positivity for CD56, focal nuclear positivity for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1), and strong positivity throughout for synaptophysin. The proliferation fraction was about 50–60%, CK CAM5.2, chromogranin, SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX10), the melanoma markers MelanA and Human Melanoma Black 45 (HMB45) were all negative. In view of these findings, a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma with cytological features not supporting a small cell subtype, likely metastatic from a lung primary, was suspected. The diagnosis of high-grade metastatic large cell neuroendocrine lung carcinoma was confirmed via a high-resolution CT scan, positron emission tomography scan, and CT-guided lung biopsy, 1 year after her initial presentation. A further CT scan of the abdomen revealed an indeterminate 9 mm left adrenal nodule, but no other metastases were identified.

Treatment options were discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting, and 4 months after her iris biopsy, she was started on palliative chemotherapy, namely a combination of carboplatin and etoposide, with a plan of eventually doing consolidation thoracic radiotherapy. From the ocular perspective, she was kept on topical cyclopentolate 1% once daily, dexamethasone 0.1% four times a day, dorzolamide hydrochloride and timolol maleate twice a day, preservative-free 0.15% sodium hyaluronate (Hyabak®) as required, and retinol palmitate ointment (VitA-POS®) once at night, all in the left eye. She was also kept on oral acetazolamide 250 mg twice daily, when required.

Around 1 month into her chemotherapy, she reported increased left eye pain. The left VA had deteriorated to 5/60 (right 6/6) and examination of the left eye revealed diffuse hyperaemia, 1+ anterior chamber cells, new posterior synechiae, a raised IOP of 40 mm Hg, and a dense white cataract with no fundal view, on top of the previous findings of rubeosis iridis and iris metastatic deposit. Furthermore, a scleral nodule was noted to have developed at the transcorneal biopsy site, thought to be seeding from the metastatic iris deposits. Because of these findings, she was started on once daily preservative-free latanoprost eye drops in the left eye and advised to use acetazolamide 250 mg twice daily on a regular basis.

She then started to improve, as the left IOP decreased to 22 mm Hg within 3 days, and a restaging CT scan showed a decrease in the size of the lung adenocarcinoma. She was therefore kept on the same topical ocular treatment, oral acetazolamide was stopped 1 week after starting, and the chemotherapy course was continued.

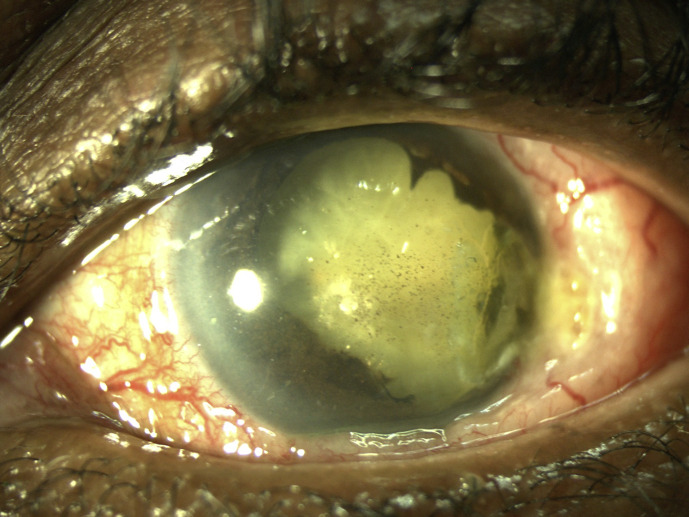

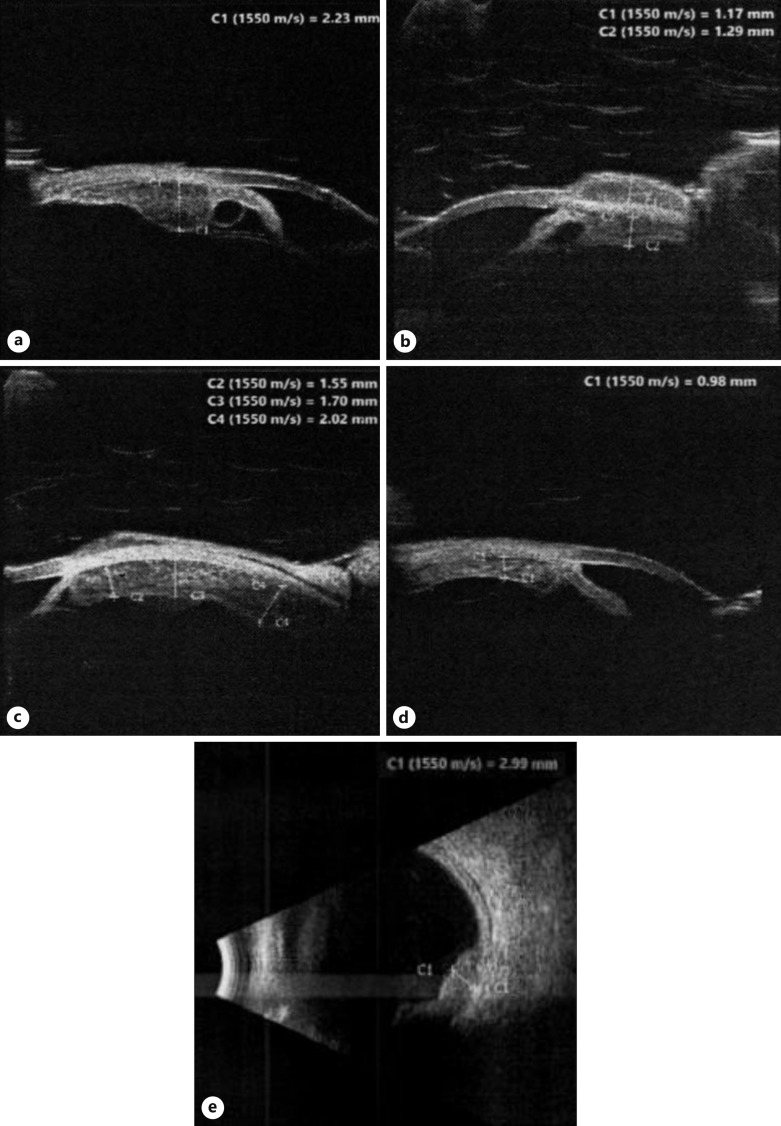

After six chemotherapy cycles, the limbal scleral nodule regressed and US biomicroscopy and B-scan US showed regression of the ciliary body metastatic lesion. There was no evidence of intraocular inflammation and her left IOP was 34 mm Hg. In view of her good response to chemotherapy, radiotherapy was deemed unnecessary. Unfortunately, 3 months after finishing her chemotherapy, the scleral nodule at the previous biopsy site was noted to have recurred and was larger and more prominent than before, shown in Figure 2. Her left VA was now counting fingers. US biomicroscopy confirmed the progression of the left eye metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, with 360-degree involvement of the left ciliary body, shown in Figure 3a–d. Furthermore, US B-scan revealed a bi-lobed inferotemporal choroidal lesion (3 mm thick) with adjacent retinal detachment shown in Figure 3e. In view of this progression, a restaging CT scan was done, which showed doubling in the size of her lung primary with no other distant metastases. Other than some generalized muscle aches, she remained asymptomatic, with no respiratory issues. Second-line chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine was started, 5 months after completing her platinum-based chemotherapy course. However, vincristine was dropped after her first cycle as she developed vincristine-related peripheral neuropathy, with severe right foot pain affecting her mobility.

Fig. 2.

Anterior segment photo showing a more prominent nodule at the biopsy site (temporal limbus), dense white cataract, posterior synechiae, pigmented keratic precipitates, and an irregular, atrophic iris.

Fig. 3.

US biomicroscopy showing 360-degree extension of the left ciliary body lesion, with snapshots at the (a) 9 o’clock position, (b) 12 o’clock position, (c) 3 o’clock position, and (d) 6 o’clock position. e US B-scan showing a bi-lobed inferotemporal choroidal lesion with adjacent retinal detachment.

Unfortunately, despite this, the tumour continued to worsen with an increase in the size of the lung primary along with the iris and choroidal deposits. A restaging CT scan revealed new right enlarged nasopharyngeal lymph nodes, which were histologically confirmed to be metastases through an US-guided fine needle aspiration. A chemotherapy rechallenge with carboplatin and etoposide did not stop progression, and palliative radiotherapy (30 Gy in 10 fractions) to the iris, nasopharyngeal nodes, and lung primary was given. However, the ocular and nasopharyngeal lymph node metastases continued to worsen, and after discussion with the patient and her family, supportive palliative care was started. She passed away 6 months later, a bit less than 4 years since her initial presentation.

Discussion

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is a rare, aggressive, and fast-growing form of NETs, arising predominantly in the lung and prostate. Its incidence worldwide is increasing, representing 2–3.5% of all lung cancers [3]. It is a high grade and poorly differentiated (grade 3) subtype of NETs, which carries a poor prognosis. Patients typically present with widely metastatic disease, with a 20% 5-year survival rate [4]. However, LCNEC metastasis to the eye is rare and, in fact, there are only 3 other cases of ocular metastasis reported [5].

In our patient, eye pain and photophobia due to the uveal metastasis were the first presenting features. These masquerade features were initially diagnosed as episcleritis. However, repeated presentations with progressive features such as intractable hyperaemia, rubeotic glaucoma, rapidly developing cataract, deteriorating vision, and development of a lesion in the iris stroma and ciliary body raised suspicion of a more sinister cause. It was only when a lung CT scan was performed that the incidental right upper lobe lesion was picked up, raising the possibility of a metastatic neoplasm. In fact, there was a 12-month delay in making the definitive diagnosis of LCNEC with ocular metastasis from her initial presentation. This emphasizes the importance of understanding the heterogeneity in the presentation and behaviour of NETs, especially high-grade LCNECs; when these are picked up, they are often already advanced and metastatic.

As mentioned previously, LCNEC ocular metastasis is extremely rare, with our case being the fourth reported in the literature. Most NET metastases to the orbit seem to arise from the gastrointestinal tract, whilst intraocular uveal metastases mostly owe their origins to bronchopulmonary tumours, as in our case [2]. The commonest presenting features of orbital metastatic NETs are a mass and diplopia, with inflammatory symptoms and visual failure being less common [2]. On the other hand, uveal metastatic NET most frequently present with decreased vision [6]. It is not common for NETs to present with ocular symptomatology before symptoms or signs from the primary site. From the limited literature available, only 22–30% of patients present with ocular or orbital disease first [2]. This heterogeneity in presentation and metastatic pattern emphasizes the importance of having a low threshold for referral to ophthalmology and for systemic investigation in cases of unexplained, refractory ocular symptomatology. It also underlines the integral role of multidisciplinary management in complex cases. Early recognition of suspicious symptoms and signs would allow prompt investigation of the patient.

Unfortunately, no clinical sign or radiological feature is diagnostic for metastatic NETs. Imaging techniques aid identification and localization, but rarely shed light on the tumour composition. On CT scan, orbital metastatic NETs usually appear as contrast-enhancing soft tissue masses, with similar density to extraocular muscles on magnetic resonance imaging [7]. Scintigraphy with Iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) or with the somatostatin analogue Indium-111 octreotide is also useful, with a reported sensitivity of 60–70% [2]. However, the gold standard for diagnosis remains histopathological analysis and immunohistochemistry via biopsy of the tumour, with subsequent localization of any systemic metastases with radionucleotide scans. In patients in whom the identification of the orbital or ocular NET metastasis precedes the diagnosis of the primary tumour, as in our patient, biopsy of the ocular lesion might give a definitive diagnosis or direct investigations. It should also be considered in patients in whom there is no other lesion amenable to biopsy. Of note, investigations for a familial syndrome, possibly including genetic testing, should also be considered in NETs as these can form part of multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome 1 or 2 (10% of cases), von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and type 1 neurofibromatosis [2]. A detailed discussion of the immunohistochemistry features of NETs is beyond the scope of this report. However, it is worth mentioning that TTF1, which was positive in our case, has been reported to be a highly specific marker for primary lung adenocarcinomas and is useful in differentiating this from adenocarcinoma lung metastases [8].

The treatment of metastatic orbital or ocular NETs depends on the patient’s systemic disease, the status of the eye, and the histological diagnosis. There is currently no universally accepted guideline for treatment due to disease rarity; however, the available literature suggests that for orbital NETs, local excision might be enough when small, whilst excision with palliative external beam radiotherapy should be considered for larger orbital metastases [2, 9]. Additional systemic chemotherapy may also be used. In the case of intraocular NETs, systemic chemotherapy is often given first line, with further radiotherapy if needed. If the ocular or orbital metastases are unresponsive to the other forms of treatment, exenteration or enucleation might be ultimately required.

With regard to chemotherapy, whilst a variety of options are available, streptozotocin-based regimens are generally used for well-to-moderately differentiated NETs (grade 1 or 2), with platinum-based chemotherapy used for poorly differentiated NETs (grade 3) [10]. In LCNEC, the first-line systemic treatment is etoposide-platinum chemotherapy, as given in our patient. Due to the lack of guidelines about second-line treatment, patients who experience treatment failure would have a poor prognosis. The FOLFIRI chemotherapy regimen, which includes leucovorin calcium, 5-fluorouracil, and irinotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, has been shown to be effective in grade 3 NETs [11]. Intravitreal topotecan has also been used with good success by Ip et al. [5] in 1 case of LCNEC with intraocular metastases, alongside systemic FOLFIRI chemotherapy. In addition, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents have been used in LCNEC iris metastases with some success [5]. However, even though promising, more data on the effectiveness of these treatments are needed. With regard to radiotherapy, there are conflicting reports on its effectiveness with some authors labelling NETs as radioresistant, whilst others maintain that it may still have a role to play in some cases [2]. Furthermore, the use of radiotherapy must be weighed against the risk of radiation injury to the ocular and surrounding orbital tissues. In our patient, in view of her good initial response to chemotherapy, radiotherapy was deemed unnecessary, as were cataract surgery and intravitreal bevacizumab injections due to the risk of further tumour seeding. Cyclodiode laser to circumvent the raised IOP was also thought to be unwise in view of the potential risk of scleritis and hypotony, which could have potentially led to a painful eye requiring enucleation.

Our experience shows that even though effective, systemic chemotherapy only temporarily decreases the NET load. Whilst both the primary LCNEC and the ocular metastasis initially improved with the etoposide-platinum chemotherapy, when this course finished, they both worsened with further choroidal spread. Furthermore, even after two further courses of chemotherapy and one full course of radiotherapy, these continued to worsen possibly showing some element of resistance. This corroborates with published reports and emphasizes the need for further research and development of a treatment guideline [2, 9]. This case also highlights the importance of a good, exhaustive examination and inclusive of an ophthalmological examination. First, the tumour was only picked up when the ocular metastasis was noted, and therefore, early detection of the ocular metastases might hasten the treatment of the primary tumour. Secondly, the regular examination of the ocular metastasis helped gauge tumour response to the systemic chemotherapy; when the systemic condition worsened, so did the ocular disease. A low threshold for referral to ophthalmology and for systemic investigation in cases of unexplained, refractory ocular symptomatology is recommended, given the heterogeneous presentation, rarity, and poor prognosis of these tumours.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all allied health professionals at Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre and Sheffield Ocular Oncology Service for their unending dedication and care towards the patient in this case report.

Statement of Ethics

This case report was written in accordance with guidelines for human studies and conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective review of patient data did not require ethical approval in accordance with local/national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images, prior to their passing away. We have taken steps to ensure that information revealing the subject’s identity is avoided and the patient is not identified by their real name.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors have no additional funding resource and are self-funding this publication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.J.C., M.A., S.M.S., and S.S. Writing and original draft preparation: Y.J.C., M.A., and B.N. Writing, review, and editing: Y.J.C., M.A., B.N., S.M.S., and S.S. Image acquisition: Y.J.C. and M.A. Supervision: S.M.S. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors have no additional funding resource and are self-funding this publication.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data have been included in this case report. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Zimmerman LE, Stangl R, Riddle PJ. Primary carcinoid tumor of the orbit: a clinicopathologic study with histochemical and electron microscopic observations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101(9):1395–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehta JS, Abou-Rayyah Y, Rose GE. Orbital carcinoid metastases. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(3):466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Battafarano RJ, Fernandez FG, Ritter J, Meyers BF, Guthrie TJ, Cooper JD, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: an aggressive form of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(1):166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao L, Li ZW, Wang M, Zhang TT, Bao B, Liu YP. Clinicopathological characteristics, treatment and survival of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: a SEER population-based study. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ip CS, Raizen Y, Goldfarb D, Kegley E, Munoz J, Schefler AC. Peripapillary neuroendocrine carcinoma metastasis: a novel approach to treatment. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2021;7(5):316–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fan JT, Buettner H, Bartley GB, Bolling JP. Clinical features and treatment of seven patients with carcinoid tumor metastatic to the eye and orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119(2):211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC, Peyster RG, Conner BE, Green HA. Orbital metastasis from a carcinoid tumor: computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and electron microscopic findings. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105(7):968–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reis-Filho JS, Carrilho C, Valenti C, Leitão D, Ribeiro CA, Ribeiro SG, et al. Is TTF1 a good immunohistochemical marker to distinguish primary from metastatic lung adenocarcinomas? Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196(12):835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen A, Haghighi A, Liang T, Lee OT, Gange W, DeBoer C, et al. Metastatic neuroendocrine tumors mimicking as primary ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2022;26:101425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Angelousi A, Kaltsas G, Koumarianou A, Weickert MO, Grossman A. Chemotherapy in NETs: when and how. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(4):485–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hentic O, Hammel P, Couvelard A, Rebours V, Zappa M, Palazzo M, et al. FOLFIRI regimen: an effective second-line chemotherapy after failure of etoposide: platinum combination in patients with neuroendocrine carcinomas grade 3. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19(6):751–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data have been included in this case report. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.