Abstract

HIV disproportionately impacts US racial and ethnic minorities but they participate in treatment and vaccine clinical trials at a lower rate than whites. To summarize barriers and facilitators to this participation we conducted a scoping review of the literature guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Studies published from January 2007 and September 2019 were reviewed. Thirty-one articles were identified from an initial pool of 325 records using three coders. All records were then assessed for barriers and facilitators and summarized. Results indicate that while racial and ethnic minority participation in these trials has increased over the past 10 years, rates still do not proportionately reflect their burden of HIV infection. While many of the barriers mirror those found in other disease clinical trials (e.g., cancer), HIV stigma is a unique and important barrier to participating in HIV clinical trials. Recommendations to improve recruitment and retention of racial and ethnic minorities include training health care providers on the importance of recruiting diverse participants, creating interdisciplinary research teams that better represent who is being recruited, and providing culturally competent trial designs. Despite the knowledge of how to better recruit racial and ethnic minorities, few interventions have been documented using these strategies. Based on the findings of this review, we recommend that future clinical trials engage community stakeholders in all stages of the research process through community-based participatory research approaches and promote culturally and linguistically appropriate recruitment and retention strategies for marginalized populations overly impacted by HIV.

Keywords: HIV clinical trials, ethnic and racial minorities, barriers to participation, scoping review

Introduction

HIV continues to be a significant public health issue in the United States, with an estimated 1.1 million infected adults and adolescents. While the overall prevalence and incidence of HIV has stayed relatively steady over the past decade,1 racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected and have, in fact, seen an increase in infection rates. In 2017 African Americans/blacks comprised 43% of the total number of new HIV infections, with a rate per 100,000 of 41.1. Hispanics/Latinx are also disproportionately affected, with a rate of 16.2, compared with just 4.9/100,000 in whites.2 This disparity is also seen in HIV mortality rates. The overall HIV mortality rate in 2017 was 1.7/100,000, but despite significant advances in HIV treatment, which lessen negative health outcomes, African Americans’/blacks’ HIV mortality rate was 17.4/100,000, Hispanics’/Latinx’ 4.4, and multiple races was 15.3/100,000.2 Within racial and ethnic groups there are also subpopulations of those at even higher HIV risk. African American/black men who have sex with men are estimated to be at least 40 times more likely to be living with HIV than other men; they comprise 26% of all new HIV infections in the United States and 37% of all new diagnoses among gay and bisexual men.3 They are also less likely to have health care visits, are less likely to be on antiretroviral therapies (ART) and have less viral suppression.4 Similar issues are seen in low-income Hispanic/Latinx.5

The goal of ART is to both prolong life and maintain its quality by significantly lowering morbidity and mortality. More recently, it has also been used as a potential preventative through the “U = U” strategy, meaning undetectable equals untransmissible.6 In all cases, however, treatment effectiveness requires high adherence. Thus, while use and adherence to antiretroviral medications has been a significant factor in falling HIV-related mortality overall, issues such as drug resistance, long-term complications, barriers to adherence, and dosing schedules justify the need to continue research and development of new, effective alternatives,7 especially in those most vulnerable. Similarly, while the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis medication is a new and important HIV prevention tool, challenges with long-term adherence have shown the importance of the continued study of potential vaccines, especially given recent breakthroughs in understanding how to optimize antibody response to HIV.8 Vaccines could significantly reduce the number of those infected in high-risk communities, thus reducing the large reservoirs of HIV that can increase risk of infection in certain geographies.9,10

Because HIV so disproportionately affects minority communities, clinical research, both for new treatment modalities and vaccine trials, is largely contingent upon successfully enrolling minority participants in clinical research to adequately understand how these biomedical interventions affect all physiologies.11 Despite this priority, racial and ethnic minorities still do not have proportional representation in any type of clinical research. The National Institutes of Health,12 the Food and Drug Administration,13 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services14 have all developed national-level initiatives to address racial and ethnic underrepresentation in clinical research. However, clinical trial participation by racial and ethnic minorities, for any type of disease treatment, has continued to be low. Evelyn et al. reported that minorities comprised just 17% of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clinical trial participants in 185 studies.15 A more recent study showed only 7.4% of participants were African American/black and ~13.3% were Hispanic/Latinx.16

These disparities are also seen in HIV-related clinical research. Using results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study, Gifford et al.17 determined that just 14 percent of HIV-infected individuals who were receiving care reported participating in an HIV clinical trial. African Americans/blacks represent 12% of the US population, but only 5% of clinical trial participants, while Hispanic/Latinx account for 16% of the population, but represent just 1% of clinical trial participants.18,19 Minorities are also less likely to participate in vaccine trials, with whites often comprising over 70% of the participants. A systematic review of HIV vaccine trials illustrates that HIV clinical trial participants tend to be white males who have higher levels of education and income, are older, and have been diagnosed with HIV for longer periods of time.20 Recent analysis of racial and ethnic enrollment in early phase HIV vaccine clinical trials between 2002 and 2016 shows that though enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities increased from 17% to 32.7% of the total number enrolled in that time frame, new HIV diagnoses in African Americans/blacks and Hispanics/Latinx were still two to six times greater than the number proportionately represented in those trials.21 This nonproportional representation is an important disparity that could potentially lead to vaccines that are not biomedically effective for all populations.

A lack of diversity in clinical trials can have significant implications. A number of studies have found differences in drug metabolism and toxicity by race and ethnicity, including in antiretroviral drugs,22–24 immunosuppressant drugs,25 and chemotherapy.26 Examining differences between men and women and between races for certain types of grade-4 adverse events in an antiretroviral initiation trial, Tedaldi et al.27 found that women are at greater risk of developing anemia, African Americans/blacks are at greater risk of having cardiovascular or renal events, and African American/black men are at greater risk of experiencing psychiatric events. Differences by biological sex have also been observed in response to many drugs, including HIV anti-retrovirals.28 Women have been found to have a 1.5 to 1.7 times greater risk of having an adverse drug reaction compared with men, leading some drugs to have been removed from the market as a result of these sex-based adverse incidents.29 These effects may be exacerbated in women of color, who also have higher rates of chronic stress due to HIV specific stressors as well as broader environmental and sociodemographic characteristics, which may affect treatment use and effects.30

Results from HIV vaccine trials show a similar pattern. Dhalla and Poole looked at North American HIV vaccine preparedness studies and found that underrepresentation of ethnic minority communities limits the generalizability of HIV vaccine trial results.31 There is also some evidence of potential biomedical differences in vaccine effectiveness32; analyses indicate that African Americans/blacks have different levels of titers for neutralizing antibodies than whites33,34 when provided a vaccine. How these differences could affect groups is difficult to know, however, because too few African Americans/blacks and Hispanics/Latinx are participating in these trials to complete subgroup analyses.35

Importantly, there is evidence that racial and ethnic minorities do see benefit in clinical trials but are often not told about the research. Castillo-Mancilla et al.36 analyzed 2175 surveys of a racially diverse group of individuals living with HIV and found that African Americans/blacks and Hispanics/Latinx had adjusted odds ratios of 0.70 and 0.69, respectively, compared with whites when asked if they had been talked to about participating in an HIV clinical trial. Hispanics/Latinx were also less likely to know about HIV studies compared with whites and African Americans/blacks (67% vs. 74% and 76%). Several studies that have assessed patient perceptions, as well as measured the number of HIV-infected minorities who participated in research studies, found comparable rates of participation17,37–40 if they had been informed about the trials. Thus, some evidence indicates that when clinical trials are explained and offered to minorities, they consent at close to the same rates as whites.41 But understanding what barriers still exist to address in conversations, and whether interventions aimed at increasing rates of participation have been effective, has not been revisited in the literature in the past decade despite the continued disparity in participation.

The purpose of this scoping review is to expand understanding of minority participation in HIV clinical medication or vaccine trials as presented in current literature to assess how things have changed, or not, since the call by national groups to increase minority representation. Clearly, ensuring representation of racial and ethnic minorities in HIV clinical research is a public health priority and understanding why these patients do not participate is important to informing the development of interventions, as well as addressing lingering health disparities.

Methods

We conducted our scoping review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.42 This approach directs researchers to conduct a broad initial search for potentially relevant material, and then narrow results in several subsequent stages based on specific and replicable inclusion criteria.

Initially, we searched the PubMed, and Embase databases for articles published between January 2007 and September 2019. The decision to use PubMed and Embase as our primary article sources was based on their large quantity of highly relevant content and ability to apply precise and replicable search commands. Using a 12-year publication window from the last search date was intended to narrow our selection to the largest number of contemporary studies. The search strategy was built around key database indexed terms such as “HIV clinical trial” and related MeSH terms such as “minority groups” under the guidance of a trained research librarian (for complete search strategy see Appendix 1). This yielded a total of 158 articles from PubMed and 167 articles in Embase. After comparing the two search results and identifying and removing duplicates, 223 unique records were included; two were then excluded as they consisted of either a review or a brief report. Titles and abstracts of the 221 records were then screened by three of the authors based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) appeared in peer-reviewed sources; (2) included participants; (3) emphasized perceptions or participation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for HIV treatment or vaccines; and (4) racial and ethnic minorities were the majority in the sample. Records were either included or eliminated by each reviewer and questionable records were left to be determined by consensus with final determinations to be made by the primary investigator.

To assess the degree of consensus among the three reviewers, percent agreement as well as Fleiss’ Kappa were determined.43 Initial agreement was 82.0% (Kappa = 0.61). Most disagreement occurred on the basis of whether studies were addressing HIV prevention versus treatment trials. After further refining inclusion parameters, articles were again reviewed and agreement among reviewers was k = 0.89. The final sample consisted of 31 total articles that were a mixture of quantitative cross-sectional or qualitative studies on factors affecting clinical trial participation in treatment or vaccine research, or were behavioral interventions intended to increase minority intention or participation in clinical trials (see Fig. 1 for complete article inclusion flow chart). Once the final selections were made, a fourth member of the research team coded each article on the basis of trial population (percentage of each minority group represented, primary outcome measured, and barriers and facilitators assessed) (Tables 1 and 2) and then quantified the identified barriers and facilitators to provide visual representation (Figs. 2 and 3).

FIG. 1.

Inclusion flow chart.

Table 1.

Reviewed Studies on Barriers and Facilitators to Minority Participation in Clinical Trials (Treatment or Vaccine)

| Study | Findings | Barriers | Facilitators | Location | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies on perceptions of treatment clinical trials in minorities (n = 9) | |||||

| Adeyemi et al.44 |

|

Treated like guinea pig; loss of privacy; time consuming; dealing with complicated research protocols; mistrust; health problems; complicated consent | Being asked to participate; recommended by PCP | Chicago | n = 417 HIV+ patients; surveys (60% male; 40% female; 64% AA; 21% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Bass et al.45 |

|

Men: Distrust of medical system; HIV conspiracy; knew less about research implementation. Women: Medication issues (losing meds; instability; meds not working, fearing placebo; side effects) |

Men: Knowledge that more meds are not required; recommendation from family or friend; incentives Women: Safety-and-trust focused (meds safe and tested; doc recommend; knowing trusted doc in the trial) | Philadelphia | n = 50 HIV+ patients; survey (44% men; 56% women; 94% AA; 6% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Castillo-Mancilla et al.36 |

|

Study not friendly to their race; Worry about confidentiality; study complicated; do not want to be treated like guinea pig |

Belief that they might receive better health care; belief that they will be representing their race; doc recommended; incentives | 47 sites in United States and Puerto Rico | n = 2175 HIV+ patients; surveys (71% male; 26% female; 1% transgender; 40% AA; 20% Hispanic/Latinx; 6% Other/Mixed) |

| DeFreitas46 |

|

Mistrust; side effects outweigh gains; stigma | Incentives; understanding of research; if addiction could be addressed | Sacramento | n = 144 HIV+ patients; surveys (86% men; 14% women; 16% AA; 13% Hispanic/Latinx; 14% Other) |

| Floyd et al47 |

|

Research is intrusive and burdensome; fear of government; belief there is no benefit to community | Benefits to self and community; monetary compensation; own Dr. being a part of research team; past participation; family involvement | New York City | n = 622 HIV+ patients; interviews (61% male; 39% female; 66% AA; 4% American Indian/Native American; 6% multiracial/other; 29% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Garber et al.48 |

|

Never asked to participate | Prior research participation; offer the opportunity | Pittsburgh | n= 197 HIV+ patients; surveys (56% male; 44% female; 100% A A) |

| Slomka et al.49 |

|

Worried about being treated like a guinea pig | Current use of HIV medication; confidence in ability to make appointments | Urban clinic specializing in the care of lowincome persons living with HIV | n= 162 HIV+ patients; interviews (64% male; 36% female; 73.5% AA) |

| Sullivan et al.50 |

|

Unaware of available studies; never asked to participate; treated like a guinea pig; access issues | Not evaluated | National surveillance data | n = 6892 HIV+ persons; surveys (72% men; 28% women; 55% AA; 19% Hispanic/Latinx; 4% Other) |

| Zuniga et al.51 |

|

Fear; stigma; lack of transportation; lack of language-appropriate services; not understanding disease | Self-help; access to health care; conducted in clinic where they normally receive care | San Diego | n = 40 HIV+ patients; surveys (100% women; 2% trans women; 100% Hispanic/Latinx) n = 14 Providers/Staff; surveys |

| Frew et al.59 |

|

Not discussed. | Neighborhood-based organizations offering HIV medical and treatment programs, support groups, and services (e.g., food, shelter, and clothing); favorable beliefs and attitudes toward participation; favorable social norms; perceived sense of inclusion | Atlanta |

n = 427 Individuals with unknown HIV status; surveys (43% male; 56% female; 1% transgender; 56% AA; 2% Hispanic/Latinx; 4% Asian; 1% Native American; 8% Multiracial) |

| Newman et al.60 |

|

Risk of vaccine-induced infection; risk of HIV false positivity | Shorter trial duration; provision of free medication | Los Angeles | n= 123 Individuals with unknown HIV status; interviews (69% male; 31% female; 14% AA; 37% Hispanic/Latinx; 15% Asian Pacific Islander, Native American, and others) |

| Richardson et al.61 |

|

Fear of side effects; concerns about testing positive; limited knowledge of research trials; stigma | Cash compensation; confidentiality of participation; public transportation, and food/grocery vouchers | Online sample | n=189 Individuals with unknown HIV status; surveys (100% men or trans women; 100% AA) |

| Westergaard et al.62 |

|

Conspiracy; medical mistrust (although not significant with willingness to participate) | Belief that racial/ethnic groups are at greater risk for HIV infection | Chicago | n = 601 Individuals with unknown HIV status; surveys (32.5% Mexican American; 34.5% AA) |

| Corbie-Smith et al.52*Formative work for intervention (Table 2) |

|

Not discussed | Integrating HIV trials with existing community services, organizations, and structures, engaging various segments of the community; conducting research using a personal approach | Rural Communities in Eastern North Carolina | n = 76 community leaders and service providers; focus groups (27% male; 73% female; 41% AA; 9% Hispanic/Latinx; 3% multiracial) n = 35 HIV+ Individuals; interviews (60% male; 40% female; 86% AA; 14% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Isler et al.53 *Secondary analysis of Corbie-Smith et al.52 study (see above) |

|

Not discussed | Balancing accessibility and confidentiality, establishing credibility, and facilitating community control of MHU implementation important to success | Rural Communities in Eastern North Carolina | n = 76 community leaders and service providers; focus groups (27% male; 73% female; 41% AA; 9% Hispanic/Latinx; 3% multiracial) n = 35 HIV+ Individuals; interviews (60% male; 40% female; 86% AA; 14% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Moutsiakis and Chin54 |

|

Misinformation; stigma; fear; medical mistrust; limited knowledge of clinical trials | Being “single”; having close friends with HIV; being gay | Unspecified Midsized US city | n= 11 HIV− or Unknown HIV status; Interviews (55% male, 45% female; 100% AA) |

| Rivera-Goba et al.55 |

|

Stigma; treated like a guinea Pig | Understanding the purpose of the research; altruism | Bethesda | n = 35 HIV+ minorities; focus Group and Interviews (63% male; 37% female; 54% AA; 3% American Indian/Alaska Native; 8.6% multiracial) |

| Slomka et al.56 |

|

Time consuming; having to travel; being treated like a guinea pig; mistrust due to lack of adequate information and/or medical care and monitoring within a study; conspiracy theories | Monetary compensation; help medical science; help oneself or one’s family, especially if affected by the diseases being studied; access to health care; access to new, better and/or free medications; learning about the risks associated with HIV and drug use; provided with necessary information and acknowledgement of their contribution to the study | Houston | n = 37 HIV+ and HIV− drug using minority patients; interviews (54% male; 56% female; 97% AA) |

| Toledo et al.57 |

|

Limited awareness about HIV research; stigma; medication side effects | Altruism; personal gain; trustworthy trial staff; convenient location and schedules; involvement of CBOs | San Francisco | n = 36 HIV+ and HIV− participants; interviews (56% male; 44% female; 50% AA; 50% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Wolak et al.58 |

|

Lack of understanding about clinical research; fear of changing medication regimen; disclosure of HIV status; distrust of medical system; HIV conspiracy theories | Extra medical attention; helping others with HIV/AIDS; doctor recommendation and trust; acquiring more information about HIV clinical trials | Philadelphia | n = 26 HIV+ patients; focus groups (46% male; 54% female; 92% AA; 4% Hispanic/Latinx; 4% Native American) |

| Qualitative studies on perceptions of vaccine clinical trials (n = 4) | |||||

| Andrasik et al.63 |

|

Absence of existing relationships between research organizations and AA MSM; poverty; lack of resources; lack of science literacy; medical mistrust; stigma | Compensation; CBOs as partners; investment in the AA community; efforts to educate the black community | Four urban areas (Atlanta, Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco) | n= 15 Individuals of unknown HIV status; focus Groups (100% men; 93% AA, 7% Afro-Latino; 7% multirace) (continued) |

| Brooks et al.64 |

|

Mistrust and fear of government; conspiracy theories (i.e., responsible for epidemic); fear of vaccine-induced infection; stigma; physical side effects; false induced HIV− positive results | Monetary compensation; convenience of study; sufficient and appropriate study information; personal benefits; altruism | Los Angeles | n = 32 Patients of unknown HIV status; focus groups (58% male; 42% female; 100% Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Newman et al.65 |

|

Fear of vaccine-induced HIV infection; physical side effects; uncertainty about vaccine efficacy; uncertainty about other vaccines; mistrust of government-sponsored research; low perceived HIV risk; study demands; HIV stigma. | Protection against HIV infection; free insurance and medical care; altruism; monetary incentives | Los Angeles | n = 58 Individuals of unknown HIV status; focus group participants (63% male; 37% female; 35% AA, 56% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Voytek et al.66 |

|

Needles; medical distrust; side effects; treated like a guinea pig | Monetary compensation; personal benefits; protection from HIV; altruism | Philadelphia | n= 17 Individuals of unknown HIV status; interviews (100% women; 100% AA) |

AA, African American; CBOs, community based organizations; MHU, mobile health units; MSM, men who have sex with men; PCP, primary care physician.

Table 2.

Reviewed Interventions to Increase Minority Participation in Treatment or Vaccine Clinical Trials

| Intervention | Author(s) | Summary | Outcomes | Location | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Community Liaison Program | Kelley et al.67 |

|

High acceptance of participatory engagement and HIV vaccine messaging Process data indicate participants had increased awareness and many were willing to share information on vaccine trials with their community | National, United States | Seven volunteer liaisons (71% women, 28% male; 71% AA, 14% white; 14% Latina) reached n = 644 (demographics not provided) |

| EAST | Corbie-Smith et al.68 |

|

Materials developed were based on the Theory of Reasoned Action, Social Cognitive Theory, the concept of social support | South Eastern United States (rural) | Formative work was qualitative. See above: Corbie-Smith et al.52 No intervention results |

| Pilot Intervention *Pilot intervention for ACT2; no peer education (see below. Gwadz et al.76) | Gwadz et al.69 |

|

Use of pre/posttest study design Patients who attended more group intervention sessions/health education were more likely to progress to screening for CTs Variables predicted moving through the stages of screening: Older age; Medicaid ineligibility; antiviral use; previous screening consideration; consideration after intervention for screening: Willingness to participate in ACT | New York | n = 342 HIV+ individuals; (66% men; 44% women; 65% AA; 27% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| ACT2 | Gwadz et al.70 |

|

Brief, peer-driven interventions increased screening rates compared with control Structured intervention sessions increased odds of screening; most screened (71.7%) recruited/educated peers | New York City | n = 342 HIV+ individuals; (66% men; 44% women; 65% AA; 27% Hispanic/Latinx) |

| Leonard et al.71 | Same as: Gwadz et al.70 | Providing safe forum for discussing enhanced credibility of researchers/study Promotes trust/openness to screening Trained facilitators were necessary for emotional discussions on racism, etc. |

New York City | Same as: Gwadz Leonard et al.70 | |

| Gwadz et al.72 | Same as: Gwadz et al.70 | Intervention participants were 30x more likely to be screened than controls Of those screened, 55.5% were eligible for HIV/AIDS medical studies 91.7% of eligible intervention participants enrolled into observational studies vs. no controls |

New York City | Same as: Gwadz et al.70 | |

| Ritchie et al.73 | Same as: Gwadz et al.70 | Qualitative exploration of experiences with intervention Intervention improved knowledge and positive attitudes toward ACTs, increased facilitators of altruism, positive social norms Components that had utility: Cultural/historical barriers to ACT discussion; session on ACT research unit; motivational interviewing Involving social network members was not a facilitator |

New York City | Sub-sample of above: Gwadz et al.70 n = 37 HIV+ persons (51.4% male; 48.6% female; 62.2% AA; 27% Hispanic/Latinx; 10.8% White/bi- or multiracial) |

ACT, AIDS clinical trials; CT, clinical trial; EAST, Education and Access to Services and Testing; PLWHA, people living with HIV/AIDS; RCT, randomized control trial.

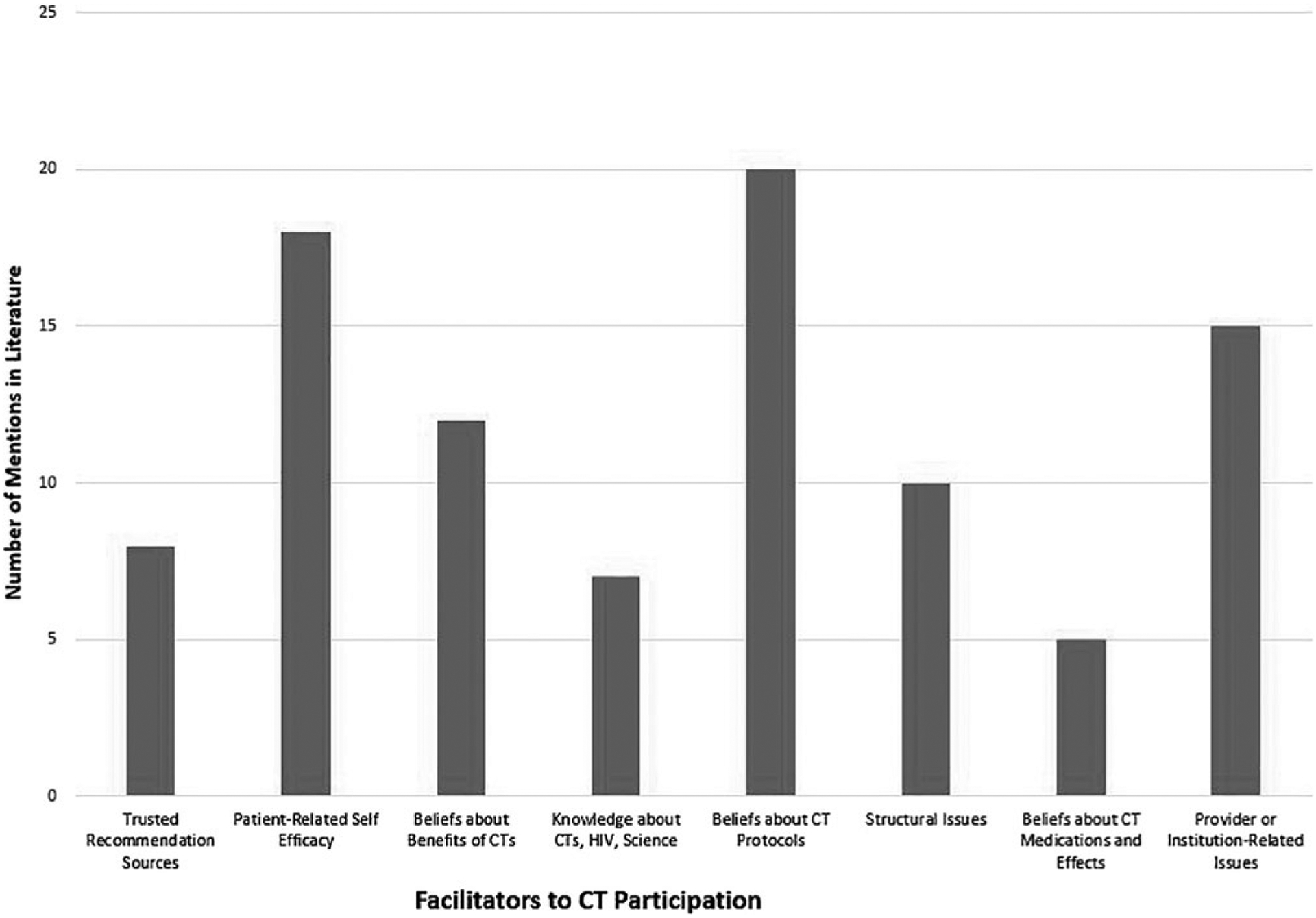

FIG. 2.

Summary of barriers to HIV-related CT participation (treatment or vaccine) in minority patients. CT, clinical trial.

FIG. 3.

Summary of facilitators to HIV-related CT participation (treatment or vaccine) in minority patients. CT, clinical trial.

Results

All 31 studies were conducted between 2007and 2019. Most occurred in major urban cities across the United States, including Atlanta, Boston, Los Angeles, New York City, and Philadelphia, and participants were recruited at health care centers or AIDS service organizations. Sixteen of the studies explored perceptions of racial and ethnic minorities living with HIV about participating in treatment clinical trials.

Of these, nine were cross-sectional surveys36,44–51 and seven were qualitative assessments.52–58 Another eight studies addressed factors to participating specifically in a vaccine trial (four cross-sectional,59–62 four qualitative63–66). The remaining studies reported on small pilot or full randomized behavioral interventions aimed at increasing intention to or actual participation in a clinical trial. In total, four behavioral interventions have been developed or tested to increase participation.67–70 One reviewed is a pilot test for a larger randomized intervention but was sufficiently different in content and implementation that it was reviewed separately.69 There were also three subanalyses71–73 done for one intervention70 and they are also included (Tables 1 and 2).

Cross-sectional and qualitative studies of medication and vaccine clinical trials

Barriers to participation.

Some common themes emerged from the studies focusing on barriers to clinical trial participation among racial and ethnic minorities in both treatment and vaccine studies. Specifically, mistrust of medical institutions and fears of being used as guinea pigs, stigma, cost, side effects, accessibility, and importantly, not being asked to participate were seen across a number of studies.36,44–51

Among black participants, the worry of being a “guinea pig” emerged frequently as many people are concerned about “being experimented on.”36,44,45,49,50,54–56,58,61,66 In fact, when Rivera-Goba et al.55 asked racial and ethnic minorities with HIV about barriers to participation, some participants specifically cited the Tuskegee Syphilis experiments. Wolak et al.58 also found that “being a guinea pig” was a significant reason, especially for minority men, to not participate. As such, the past unethical actions of the medical community are still in the minds of today’s patients when making decisions about participating in clinical trials. A number of studies also found conspiracy beliefs about the origins of HIV or how the government was responsible for its spread.44,55,57,60,63 This general distrust of the medical system and government overall were pervasive throughout the studies for both medication and vaccine clinical trials. This might be further exacerbated in vaccine trials where you are asking a healthy person to try a medication they may have negative interactions to. As a result, many felt these studies were not “friendly” to their race36 or would not benefit their community.47

Importantly, stigma is an important consideration in HIV clinical trials, which is a unique barrier not seen in other types of clinical trial disparities (e.g., cancer). HIV stigma is important to patients who may be concerned about disclosure of their status or being seen taking part in an HIV-related treatment or vaccine trial.46,51,54,55,57,58,61,63,64,65 For example, Brooks et al.64 did focus groups among Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinx in Los Angeles to discuss barriers to vaccine trial participation. HIV stigma emerged as a major barrier, with participants noting that negative community beliefs about HIV and AIDS are still prevalent and that many may only participate in a trial if it was “secret” and other people would not know about their participation.

Medication barriers were also frequently noted. Many individuals were concerned that they would be placed in a placebo group and consequently derive no medical benefit from participation.45 On the other hand, if they did receive the trial medication there was fear that it would not work on them or that the new medication would lead to negative side effects, both short-term and long-term.50,54,57,60,61,63,66 Many people were also concerned about losing the stability of their current medication regime. These issues were found in at least one study to be especially salient for minority women.45 It should be noted, though, that many studies indicated little participant awareness of the clinical trial process. Bass et al.45 noted that most participants answering questions about clinical trial participation barriers did not understand or had never heard of placebos or randomization. A brief tutorial on the clinical trial process was developed for that project to ensure equal understanding among participants. This lack of knowledge about clinical research was also noted in a number of other studies, especially those related to vaccine trials, where concerns about becoming infected with HIV were an important barrier.60–63

Moving beyond psychosocial barriers, logistical barriers were also important to racial and ethnic minorities. For example, accessibility was a key barrier to participation in clinical trials, as were the time it takes to participate and the perception that they are only for English-speaking patients. Individuals reported that they were less likely to participate in clinical trials if they did not live close to the clinical trial sites or could not easily access the sites by public transportation.44,51,56 Newman et al.65 noted that the study demands were also important, including increased doctor’s visits and time to do assessments. In addition, individuals who were primarily Spanish-speaking cited language as a major barrier to participation in clinical trials.64

Surprisingly, awareness of trials is a major barrier to clinical trial participation among many racial/ethnic minorities; many report they are simply not being asked to participate. For example, Adeyemi et al.44 found that in a group of racial/ethnic minority HIV patients, only 29% had ever been asked to participate in a clinical trial. Likewise, Garber et al.48 surveyed 200 African Americans/blacks living with HIV and found that only 57% had ever been asked to participate in a treatment trial; of those who were, 86% agreed to participate. They found having been asked to participate was also more closely correlated with future participation, compared with barriers such as medical mistrust or negative beliefs about researchers.

Motivators of participation.

Importantly, numerous factors that increase participation of racial/ethnic minority patients in clinical trials have also been identified. Participants have expressed the importance of being sufficiently informed about clinical trials and what participation entails, as well as what the appropriate steps are should adverse effects occur.44,46,48,52 Corbie-Smith et al.52 found that if research is conducted with a personal approach and integrated in existing trusted community agencies, racial and ethnic minorities would be more inclined to participate. Other studies have indicated that participation is more likely if it is convenient for them and if there are incentives, including money, the provision of health care, and access to new or better medications.36,45,46,51,58,60,61 Being treated with respect, made comfortable by the researcher, trusting the researcher, feeling a sense of partnership, and receiving culturally appropriate services were also noted as motivators of participation.44,36,56,57 For example, Rivera-Goba et al.55 found that Hispanic/Latinx and African American/black individuals were more likely to participate in trials if they felt like they were in a partnership. Particularly, they found that individuals preferred to be approached by someone from a similar background that made them feel like they were helping, rather than just being given instructions.

Beliefs about participation.

Beliefs about participation are the result of participants’ life experiences that affect their decision to participate in research. Both altruism and the understanding of the purpose of research are key factors in the decision to participate in a clinical trial.55 Some people feel it is their duty to participate in a trial if they have the opportunity because it can benefit people beyond themselves in the larger community who may not have the chance to participate or may be fearful to participate.55,64 Some studies noted that these beliefs about civic responsibility may be important to some individuals.47,55,59 Slomka et al.56 noted that discussing how participation might help not only themselves but family or friends affected by HIV was important to the participation decision. Being optimistic about finding a cure for HIV and feeling that their participation can make a difference were also significant beliefs associated with willingness to participate. This was especially seen in the vaccine trial studies, where the benefits of being protected from HIV was a significant motivator65,66 for individual reasons but also as a community-level reason that may protect others from HIV. Overall, studies noted that participants understand that clinical research is necessary for advancing the knowledge and treatments for HIV, and if that benefit can be framed in the context of one’s community, they are more open to participating.

Interventions aimed at increasing minority participation in clinical trials

Although increasing recruitment of minorities into HIV treatment or vaccine clinical trials has been articulated as an important priority, very few behavioral interventions have been initiated to increase enrollment. To date, only four interventions have been identified with the express outcome of enrolling more racial/ethnic minorities or increasing decision making around clinical trial participation. Only one—ACT2-was a large randomized trial.70 In this study, intervention participants received 6 h of small group educational activities that were led by peer educators. Results indicated that a multicomponent peer-driven intervention did increase rates of screening for and enrollment in treatment clinical trials in New York City. Subanalysis of the intervention data indicates that intervention participants were 30 times more likely to be screened for clinical trials and of those screened, 55% were eligible.71,72 A qualitative study with participants also indicated the intervention improved knowledge and positive attitudes toward clinical trials as well as increased a sense of altruism.73

A pilot intervention, which served to inform the ACT2 study, used a similar small group format but was not conducted with peer educators.69 Another study reports on the development of a community-based participatory engagement intervention,67 but intervention details and results are not discussed. The last is a small pilot testing specialized materials to increase understanding of clinical trials.68 Overall, although small in number, results indicate that interventions focused on the needs of racial and ethnic minorities do have positive effects on intention and enrollment in clinical trials.

Discussion

Although there are historical and cultural barriers to racial and ethnic minority participation in HIV clinical trials, this review indicates that much of the work to understand those barriers has been done. This work, however, has not been translated to better recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities over the past decade; they still participate at lower levels than whites despite being disproportionately affected by HIV. It is clear that there is a need for culturally and linguistically relevant recruitment, outreach, and retention, as well as interventions that address the unique barrier of HIV stigma and the complex relationship racial and ethnic minorities have with the health care system. Specifically, mistrust of medical institutions and fears of being used as guinea pigs must be considered when developing interventions and programs for the engagement of racial and ethnic minorities in HIV clinical trials. Extra efforts must be made to establish trust within these communities, including the meaningful engagement of community members and heavily impacted communities in all stages of the research process. Community-based participatory action research,74 as an evidenced-based partnership approach to research that equitably involves community members, practitioners, and academic researchers in all aspects of the process, can address some of these structural barriers to engagement and participation in HIV clinical trials.75

New work in establishing how best to recruit racial and ethnic minorities in vaccine trials is increasingly important as we focus research dollars on the development of an effective vaccine. While many of the studies reviewed here were cross-sectional in nature, some of the new research in vaccine participation is attempting to understand barriers through a theoretical lens. For example, Frew et al.76 applied an extended model of reasoned action with black/African Americans to understand how sociopsychological issues (e.g., beliefs about benefits to themselves or communities) and network issues (e.g., beliefs about the mission of the research or the organization carrying it out) might influence participation in vaccine trails. They found that significant effects demonstrated the importance of positive attitudes toward HIV vaccine research and health research, perceived social support for participation, engagement with HIV as a health issue, and the perceived relevance of the research site were all critical to whether participants would be amenable to being part of a vaccine trial. This interplay of personal and more global influences is crucial to understanding how best to intervene with racial and ethnic minorities in that it goes beyond just offering a trial or providing information on the trial. Instead, interventions that address a more social ecological approach may be more effective in recruitment efforts, as they have in other HIV studies on prevention and HIV testing.77,78

This was seen in a number of the qualitative studies in which community and the need for trust of those doing the research and engagement with their community were reported.52–58,63 This coincides with the one large randomized control trial (RCT) aimed at increasing racial and ethnic participation in clinical trials70 that used community peer educators to deliver educational activities. More interventions like this should be used by clinical sites to increase participation in these harder-to-reach groups. But no new interventions have been reported in the literature since 2011, despite the continued problem of recruiting racial and ethnic minorities.

Importantly, the troubled history between medical research and racial and ethnic communities places the burden of change on the health care community. That is, it is the duty of health care providers to make efforts to include members of racial and ethnic minorities in all HIV studies so the trials more closely represent the population of people living with HIV. Current studies continue to show the stigma experienced or anticipated by minorities and women with HIV in the health care system,79 illustrating the need for designing studies to increase participant in clinical trials that address this stigma. Polanco et al.80 suggest that building interdisciplinary teams that include researchers with racial and ethnic diversity can help build an infrastructure that makes it easier to not only recruit these populations but to have them agree to participate. They developed a team called “Adelante” (Spanish for “forward”) to address four key attributes—having concordant researchers to the populations they were recruiting, providing an atmosphere that fosters participatory decision making, empowering the team by increasing their involvement in recruiting, and creating cohesiveness among team members. This strategy could be essential to clinical and medical settings being more successful at recruiting racial and ethnic individuals and is a model that could be easily replicable.

In the end, some key changes in recruitment strategies and implementation of salient interventions that address the unique needs of racial and ethnic minorities living with HIV could substantively change the look of those participating in medication and vaccine clinical trials. A recent innovative example used community advisory boards and “crowdsourcing” to engage communities by getting them to solve a problem and sharing solutions through both in person and social media channels.81 This could be applied specifically to minority patients with HIV. Clearly, receiving culturally relevant services, being respected by the researcher, and trusting the researcher or research team all help to make participants more comfortable and thereby increase the likelihood of their engaging in future research. Many individuals also want to feel that their participation is serving a greater purpose—that it will help others. Finally, studies need to be easy for participants to engage in. Physical access to studies and lack of transportation have consistently been reported as barriers to participation. Locating studies near the people with whom they recruit would help ease the difficulty that prevents many people from participating in HIV research studies. By and large, strategies to effectively engage minority populations in HIV research studies have been identified. It is necessary, however, for researchers to take the appropriate steps to address these barriers.

Limitations

Although the present study did a thorough analysis of the current literature, there are some limitations. First, there were very few studies with a majority of racial and ethnic minority participants. In fact, most of the studies found during our search either had a majority of white participants or did not report participants’ race or ethnicity. Second, our search was limited to two databases and one language. It is possible that our narrow search criteria excluded applicable reports outside of our search area. Third, although we used a thorough search strategy, we were invariably constrained by search terms and our specific emphasis on recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials; therefore, we may have inadvertently missed some relevant work on recruitment and engagement in clinical trials. Fourth, the decision to exclude reports or studies published at web sites or gray literature such as conference proceedings or institutional publications resulted from our strict inclusion criteria to include only peer-reviewed articles. This might have limited access to relevant information published in clinical trial websites and AIDS service organizations engaged in recruitment of minorities in clinical trials.

To effectively test new and emerging HIV treatments and preventive strategies, clinical trials must reflect the communities most affected. While participation in these trials has increased over the past 10 years, rates still do not proportionately reflect racial and ethnic minorities. Previous research highlights changes that can be made in trial recruitment to address this disparity. Training health care providers on the importance of recruiting diverse participants, creating interdisciplinary research teams that better represent who is being recruited, and providing culturally competent trial designs can go a long way in addressing the stark racial and ethnic disparities in HIV trials, as well as repairing the harmful past unethical practices that have created a negative relationship between racial and ethnic minorities and the medical community. Our review of the literature points to the need for health care providers and researchers to address these unique barriers as well as emphasize the motivators to understand how to better engage these populations in clinical research. The use of community-based participatory action research approaches could help alleviate some of the structural barriers identified, including stigma, by building trust with highly impacted communities and addressing community trauma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephanie Roth, Biomedical and Research Services Librarian at the Ginsburg Health Sciences Library at Temple University, for her expertise and assistance in the scoping review search.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Appendix

Search Plan

Research question

The extent of participation in HIV treatment research is suboptimal among HIV-infected racial/ethnic minority populations, notably African American, Latino, Asian, and Pacific Islander. To what degree have specific barriers been accounted for that inhibit participation in treatment research among HIV-infected racial/ethnic minorities, and have interventions targeted at increasing minority participation in HIV treatment research been successful?

List of keywords/search strings for database search

Research participation, clinical trial participation, willingness to participate in research, treatment research, HIV treatment research, willingness to participate in clinical trials, barriers, facilitators, health research study, clinical research, HIV infected, HIV positive and participation, racial/ethnic minority population and participation, African American (black) and participation, Latino (Hispanic) and participation, Asian (i.e., Chinese and other Asian derivatives) and participation, Pacific Islander (i.e., Native Hawaiian and other PI derivatives) and participation

Databases

PubMed Web of Science

Restrictions

Published dates: 2007–September 2019

Language: English

Country: United States

Subjects/age: Human adults (19+)

Example of search process on PubMed

(“minority groups”[MeSH Terms] OR (“minority”[All Fields] AND “groups”[All Fields]) OR “minority groups”[All Fields] OR “minority”[All Fields]) AND participation[All Fields] AND (“hiv”[MeSH Terms] OR “hiv”[All Fields]) AND (“therapeutic human experimentation”[MeSH Terms] OR (“therapeutic”[All Fields] AND “human”[All Fields] AND “experimentation”[All Fields]) OR “therapeutic human experimentation”[All Fields] OR (“treatment”[All Fields] AND “research”[All Fields]) OR “treatment research”[All Fields])

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016; vol. 28. 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html (Last accessed May 24, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Preliminary). 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017. 2018. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- 4.Millett G, Peterson J, Flores S, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vissman AT, Young AM, Wilkin AM, Rhodes S. Correlates of HAART adherence among immigrant Latinos in the southeastern United States. AIDS Care 2013;25:356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas GS, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA 2019;321:844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbaro G, Scozzafava A, Mastrolorenzo A, Supuran C. Highly active antiretroviral therapy: Current state of the art, new agents and their pharmacological interactions useful for improving therapeutic outcome. Curr Pharm Des 2005;11:1805–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisinger RW, Fauci AS. Ending the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauci AS. An HIV vaccine is essential for ending the HIV/AIDS pandemic. JAMA 2017;318:1535–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low MSY, Tarlinton D. HIV Vaccines: One step closer. Trends Mol Med 2017;23:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cargill VA, Stone VE, Robinson MR. HIV treatment in African Americans: Challenges and opportunities. J Black Psychol 2004;30:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health. Amendment: NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. 2017. Available at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-18-014.html

- 13.White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. 2015. Available at: https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Clinical Trial Policies. 2007. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/ClinicalTrialPolicies/index

- 15.Evelyn B, Toigo T, Banks D, et al. Participation of racial/ethnic groups in clinical trials and race-related labeling: A review of new molecular entitites approved 1995–1999. J Natl Med Assoc 2001;93:18S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downing NS, Shah ND, Neiman JH, et al. Participation of the elderly, women, and minorities in pivotal trials supporting 2011–2013 U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals. Trials 2016;17:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gifford AL, Cunningham WE, Heslin KC, et al. Participation in research and access to experimental treatments by HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1373–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Society for Women’s Health Research, United States Food and Drug Administration, Office of Women’s Health. Dialogues on Diversifying Clinical Trials; Successful Strategies for Engaging Women and Minorities in Clinical Trials. 2007. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/WomensHealthResearch/UCM334959.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Clark LT, Watkins L, Piña IL, et al. Increasing diversity in clinical trials: Overcoming critical barriers. Curr Probl Cardiol 2019;44:148–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills E, Cooper C, Guyatt G, et al. Barriers to participating in an HIV vaccine trial: A systematic review. AIDS 2004; 18:2235–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huamani KF, Metch B, Broder G, Andrasik M. A demographic analysis of racial/ethnic minority enrollment into HVTN preventive early phase HIV vaccine clinical trials conducted in the United States, 2002–2016. Public Health Rep 2019;134:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotger M, Csajka C, Telenti A. Genetic, ethnic, and gender differences in the pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral agents. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2006;3:118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Csajka C, Marzolini C, Fattinger K, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and effects of efavirenz in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003;73:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfister M, Labbé L, Hammer SM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of efavirenz, nelfinavir, and indinavir: Adult AIDS Clinical Trial Group Study 398. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dirks NL, Huth B, Yates CR, Meibohm B. Pharmacokinetics of immunosuppressants: A perspective on ethnic differences. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;42:701–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phan VH, Moore MM, McLachlan AJ, et al. Ethnic differences in drug metabolism and toxicity from chemo-therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2009;5:243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tedaldi EM, Absalon J, Thomas AJ, et al. Ethnicity, race, and gender. Differences in serious adverse events among participants in an antiretroviral initiation trial: Results of CPCRA 058 (FIRST Study). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson GD. Sex and racial differences in pharmacological response: Where is the evidence? Pharmacogenetics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. J Womens Health 2005;14:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zopf Y,Rabe C,Neubert A,et al. WomenencounterADRsmore often than do men. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:999–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JL, Littlewood RA, Vanable P Social-cognitive correlates of antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-infected individuals receiving infectious disease care in a medium-sized northeastern US city. AIDS Care 2013;25: 1149–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhalla S, Poole G. Barriers of enrolment in HIV vaccine trials: A review of HIV vaccine preparedness studies. Vaccine 2011;29:5850–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, et al. Efficacy trial of a DNA/rAd5 HIV-1 preventive vaccine. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2083–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1275–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montefiori DC, Metch B, McElrath MJ, et al. Demographic factors that influence the neutralizing antibody response in recipients of recombinant HIV-1 gp120 vaccines. J Infect Dis 2004;190:1962–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobieszczyk ME, Xu G, Goodman K, et al. Engaging members of African American and Latino communities in preventive HIV vaccine trials. JAIDS 2009;51:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Cohn SE, Krishnan S, et al. Minorities remain underrepresented in HIV/AIDS research despite access to clinical trials. HIV Clin Trials 2014;15:14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan PS, McNaghten AD, Begley E, et al. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. J Natl Med Assoc 2007; 99:242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gwadz MV, Leonard NR, Nakagawa A, et al. Gender differences in attitudes toward AIDS clinical trials among urban HIV-infected individuals from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. AIDS Care 2006;18:786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heumann C, Cohn S, Supriya K, et al. Regional variation in HIV clinical trials participation in the United States. South Med J 2015;108:107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Priddy FH, Cheng AC, Salazar LF, Frew PM. Racial and ethnic differences in knowledge and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in an urban population in the Southeastern US. Int J STD AIDS 2006;17:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gandhi M, Ameli N, Bacchetti P, et al. Eligibility criteria for HIV clinical trials and generalizability of results: The gap between published reports and study protocols. AIDS 2005;19:1885–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med 2005;3:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moher D Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleiss JL. Cohen J The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas 1973;33:613–619. [Google Scholar]; 44. Adeyemi OF, Evans AT, Bahk M. HIV-infected adults from minority ethnic groups are willing to participate in research if asked. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23:859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bass SB, Wolak C, Greener J, et al. Using perceptual mapping methods to understand gender differences in perceived barriers and benefits of clinical research participation in urban minority HIV+ patients. AIDS Care 2016; 28:528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeFreitas D Race and HIV clinical trial participation. J Natl Med Assoc 2010;102:493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Floyd T, Patel S, Weiss E, et al. Beliefs about participating in research among a sample of minority persons living with HIV/AIDS in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010;24:373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garber M, Hanusa B, Switzer G, et al. HIV-infected African Americans are willing to participat in HIV treatment trials. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:17–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slomka J, Kypriotakis G, Atkinson J, et al. Factors associated with past research participation among low-income persons living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26:496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan P, McNaghten AD, Begley E, et al. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. J Natl Med Assoc 2007; 99:242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zúñiga ML, Blanco E, Martínez P, et al. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators to participation in clinical trials in HIV-positive Latinas: A pilot study. J Womens Health 2007;16:1322–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corbie-Smith G, Isler MR, Miles MS, Banks B. Community-based HIV clinical trials: An integrated approach to underserved, rural, minority communities. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2012;6.2:121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Isler MR, Miles MS, Banks B, Corbie-Smith G. Acceptability of a mobile health unit for rural HIV clinical trial enrollment and participation. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1895–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moutsiakis D, Chin NP. Why blacks do not take part in HIV vaccine trials. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:254–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rivera-Goba MV, Dominguez DC, Stoll P, et al. Exploring decision-making of HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans participating in clinical trials. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2011;22:295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slomka J, Ratliff ER, McCurdy SA, et al. Decisions to participate in research: Views of underserved minority drug users with or at risk for HIV. AIDS Care 2008;20:1224– 1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toledo L, McLellan-Lemal E, Arreola S, et al. African-American and Hispanic perceptions of HIV vaccine clinical research: A qualitative study. Am J Health Promot 2014;29: e82–e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolak C, Bass SB, Tedaldi E, et al. Minority HIV patients’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to participation in clinical research. Curr HIV Res 2012;10:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frew P, Archibald M, Hixson B, del Rio C. Socioecological influences on community involvement in HIV vaccine research. Vaccine 2011;29:6136–6143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newman P, Duan N, Lee S, et al. Willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials: The impact of trial attributes. Prev Med 2007;44:554–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richardson S, Seekaew P, Koblin B, et al. Barriers and facilitators of HIV vaccine and prevention study participation among young black MSM and transwomen in New York City. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westergaard RP, Beach MC, Saha S, Jacobs EA. Racial/ethnic differences in trust of health care: HIV conspiracy beliefs and vaccine research participation. J Gen Intern Med 2013;29:140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andrasik MP, Chandler C, Powell B, et al. Bridging the divide: HIV prevention research and black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2014;104:708–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brooks RA, Newman PA, Duan N, Ortiz DJ. HIV vaccine trial preparedness among Spanish-speaking Latinos in the US. AIDS Care 2007;19:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, et al. HIV vaccine trial participation among ethnic minority communities: Barriers, motivators, and implications for recruitment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;41:210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voytek CD, Jones KT, Metzger DS. Selectively willing and conditionally able: HIV vaccine trial participation among women at “high risk” of HIV infection. Vaccine 2011;29: 6130–6135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelley RT, Hannans A, Kreps GL, Johnson K. The Community Liaison Program: A health education pilot program to increase minority awareness of HIV and acceptance of HIV vaccine trials. Health Educ Res 2012;27:746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Corbie-Smith G, Odeneye E, Banks B, et al. Development of a multilevel intervention to increase HIV clinical trial participation among rural minorities. Health Educ Behav 2013;40:274–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gwadz MV, Cylar K, Leonard NR, et al. An exploratory behavioral intervention trial to improve rates of screening for AIDS clinical trials among racial/ethnic minority and female persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 2010; 14:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gwadz MV, Leonard NR, Cleland CM, et al. The effect of a peer-driven intervention on rates of screening for AIDS clinical trials among African Americans and Hispanics. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1096–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leonard NR, Banfield A, Riedel M, et al. Description of an efficacious behavioral peer-driven intervention to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS clinical trials. Health Educ Res 2013;28:574–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gwadz M, Cleland CM, Belkin M, et al. ACT2 peer-driven intervention increases enrollment into HIV/AIDS medical studies among African-Americans/Blacks and Hispanics: A cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav 2014;18: 2409–2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ritchie A, Gwadz MV, Perlman D, et al. Eliminating racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS clinical trials in the United States: A qualitative exploration of an efficacious social/behavioral intervention. J AIDS Clin Res 2017;8:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ivankova NV. Applying mixed methods in community-based participatory action research: A framework for engaging stakeholders with research as a means for promoting patient-centeredness. J Res Nurs 2017;22:282–294. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez O, Lopez N, Woodard T, et al. Transhealth information project: A peer-led HIV prevention intervention to promote HIV protection for individuals of transgender experience. Health Soc Work 2019;44:104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Frew P, Archibald M, Diallo DD, et al. An extended model of reasoned action to understand the influence of individual and network level factors on African Americans’ participation in HIV vaccine research. Prev Sci 2010;11:207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martinez O, Wu E, Frasca T, et al. Adaptation of a couple-based HIV/STI prevention intervention for Latino men who have sex with men in New York City. Am J Mens Health 2017;11:181–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dyson YD, Mobley Y, Harris G, Randolph SD. Using the social-ecological model of HIV prevention to explore HIV testing behaviors of young Black college women. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2018;29:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rice WS, Turan B, Fletcher FE, et al. A mixed methods study of anticipated and experienced stigma in health care settings among women living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2019;33:184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Polanco DC, Dominquez D, Grady C, et al. Conducting HIV research in racial and ethnic minority communities: Building a successful interdisciplinary research team. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2011;22:388–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Day S, Mathews A, Blumberg M, et al. Expanding community engagement in HIV clinical trials: A pilot study using crowdsourcing. AIDS 2020;34:1195–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]