Abstract

Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) printing technology has been used in orthopaedic surgery in recent years to manufacture customized surgical cutting jigs. However, there is scarcity of literature and information regarding the optimal parameters of an ideal jig. Our study aims to determine the optimum parameters to design surgical jigs that can produce accurate cuts, and remain practical for use, to serve as a guide for jig creation in future.

Methods and materials

A biomechanical lab study was designed to investigate whether the thickness of a jig and the height of its cutting slot can significantly affect cutting accuracy. Surgical jigs were 3D printed in medical grade, and an oscillating sawblade was used to mimic intraoperative surgical cuts through the cutting slots onto wooden blocks, which were then analysed to determine the accuracy of cuts.

Results

Statistical analysis was performed on a total of 72 cuts. The cutting accuracy increased when the thickness of the jig increased, at all slot heights. The cutting accuracy also increased as the slot height decreased, at all jig thicknesses. Overall, the parameters for jig construction that yielded the most accurate cuts were a jig thickness of 15 mm, in combination with a slot height of 100 % of the width of the sawblade. Additionally, at a jig thickness of 15 mm, there was no statistically significant difference in cutting accuracy when increasing the slot height to 120 %.

Conclusion

This study is the first to propose tangible parameters that can be applied to surgical jig construction to obtain reproducible accurate cuts. Provided that a jig of 15 mm thickness can be accommodated by the size of the wound, the ideal surgical jig with a superior balance of accuracy and useability is 15 mm thick, with a cutting slot height of 120 % of the sawblade thickness.

Keywords: Three-dimensional, Printing, Surgical jig, Patient-specific, Biomechanics

1. Introduction

Utilisation of Three-dimensional (3D) printing in orthopaedic surgery has grown in recent years as its technology becomes increasingly accessible and affordable.1 Apart from manufacturing anatomical models for pre-operative planning and customised implants, 3D-printing can also be used to develop devices to guide surgical tools also known as jigs. Surgical jigs are used to improve the accuracy of bone resection so as to optimise the alignment and fixation of implants and prosthesis.2 The use of 3D-printing technology within Orthopaedic surgery has demonstrated several advantages such as a shorter operative time and reduced blood loss and fluoroscopy use.1 These surgical jigs are also patient specific and allow either accurate and precise cuts with a sawblade, or placement of screws or wires intraoperatively.3

However, despite surgeons being the end-users of 3D-printed surgical jigs, the design and fabrication of patient-specific instruments have largely been left to engineers. This is possibly due to the presumed complexity and intricacies of their construction. The economic and time costs of manufacturing patient-specific instruments in countries that do not have the technology or resources to manufacture them locally would be barriers to their utilisation as well.4 These factors, in addition to the surgeons’ limited knowledge of 3D-printed jig creation and the paucity of literature on the parameters of an ideal surgical jig, reduce the applicability of 3D-printed jigs in the clinical setting.

The aim of this study was therefore to determine the optimum dimensions of the cutting slot of 3D-printed surgical jigs that can produce accurate cuts, while maintaining their practicality in surgery.

We chose to investigate whether the thickness of a jig and the height of its cutting slot can significantly affect cutting accuracy. We chose these two factors because the dimensions of the jig together with its cutting slot form the fundamental parameters of a jig. The primary aim of the study was to identify tangible jig parameters that can be used in future as a guideline for surgeons who plan to create their own 3D-printed surgical jigs.

2. Materials and methods

A biomechanical lab study was performed to mimic actual intra-operative surgical cuts. 72 customized surgical guide jigs were designed and printed using our institution's in-house 3D printers (Formlabs3B®) in surgical grade resin. The length and width of every jig was kept uniform at 40.0 mm length by 30.0 mm width. Each jig was designed with one cutting slot in the middle, and two holes of 2.0 mm diameter (superior and inferior) to allow for placement of 2.0 mm Kirschner wires. The jigs were varied in terms of their individual thickness as well as height of the cutting slots - the two key variables of the study. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

3D-printed surgical guide jigs of varying thickness and cutting slot heights. Each jig measures 40.0 mm length by 30.0 mm width, with 2 holes of 2.0 mm diameter superior and inferior to each cutting slot.

The first variable was the thickness of each jig. The jigs were designed in three different levels of thickness, at 5.0 mm, 10.0 mm and 15.0 mm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

3D-printed jigs of varying thicknesses.

The second variable was the height of the cutting slot. A Dupuy Synthes Colibri II® oscillating sawblade (Warsaw, Indiana, United States) was used as the reference for the height of the cutting slot. The dimensions of the sawblade used were 0.6 mm thickness by 50.0 mm length by 14.0 mm width. At each height of the jigs, using the thickness of the sawblade as reference, the cutting slots were designed in four different heights, at 100 %, 105 %, 110 % and 120 %, in relation to the 0.6 mm thickness of the sawblade (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

3D-printed jigs with increasing cutting slot heights (annotated with arrows). Increasing slot heights (a) 0.60 mm, (b) 0.63 mm, and (c) 0.72 mm are equivalent to 100 %, 105 % and 120 % of the thickness of the sawblade respectively.

72 machine cut wooden blocks made of 100 % pine wood were then obtained. They were all uniform dimensions, measuring 50.0 mm length by 50.0 mm width by 50.0 mm height (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Uniform wooden blocks on which cuts were performed.

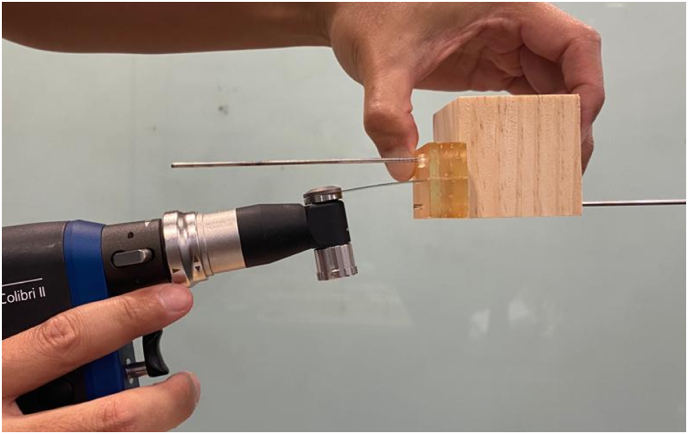

The jigs were then mounted to each wooden block using two Kirschner wires of 2.0 mm (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Jig mounted to wooden block with Kirschner wires, with demonstration of position of sawblade for actual cuts.

An experienced consultant Orthopaedic surgeon and a junior resident then performed the cuts. The oscillating sawblade was mounted to the Colibri II® power tool, and cuts were made in the wooden blocks through the cutting slots of the jigs, using the entire length of the sawblade. The sawblades were angled maximally within the confines of the cutting slot while the cuts were performed, in order to elicit the greatest degree of deviation from the perpendicular of 90° (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A standardised approach was used to perform cuts through jig cutting slots – sawblade inserted into jig and wooden block construct that was mounted onto the table.

A total of 72 cuts were performed, with the Orthopaedic surgeon and the resident performing 36 cuts each. On each wooden block, the degree of deviation from the original perpendicular angle of 90° was then measured and recorded.

2.1. Statistical analysis

For continuous data variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported and we utilised the Student t-test to analyse the mean differences between groups. The two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test was performed on the 72 measured data points to determine the effects of the cutting jig variables. A two tailed significance level of 0.05 was used for all the tests. All statistical analysis was conducted using STATA 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

The measurements were recorded. We defined the mean error as the mean deviation (in degrees) obtained for each jig. The results were compiled as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compilation of measurements of mean error (in degrees).

| Thickness |

5 mm |

10 mm |

15 mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slot height | Mean (Standard deviation) | Mean (Standard deviation) | Mean (Standard deviation) |

| 100 % | 0.66 (SD 0.52) | 0.58 (SD 0.58) | 0.42 (SD 0.49) |

| 105 % | 1.67 (SD 0.82) | 1.16 (SD 0.41) | 0.83 (SD 0.52) |

| 110 % | 4.92 (SD 0.80) | 1.25 (SD 1.13) | 0.75 (SD 0.82) |

| 120 % | 4.50 (SD 1.41) | 1.83 (SD 0.88) | 1.08 (SD 0.86) |

SD = Standard deviation.

The mean deviation decreased when the thickness of the jig increased, at all slot heights. For example, at a slot height of 100 %, the amount of deviation that resulted from using a 15 mm thick jig was 0.42 mm as compared to 0.60 mm when using a 5 mm thick jig.

There was a similar trend of increasing mean deviation, as the slot height increases. The lowest slot height of 100 % yielded the lowest mean deviation, regardless of the jig thickness. The greatest slot heights of 110 % and 120 % yielded the greatest mean deviations, at all jig thicknesses.

Overall, the parameters for jig construction that yielded the lowest mean deviation were a jig thickness of 15 mm, in combination with a slot height of 100 % of the width of the sawblade.

The greatest mean deviations were obtained with the thinnest jig of 5 mm with the largest cutting slot heights of 110 % and 120 %, at 4.92 and 4.50° of mean error respectively.

At a jig thickness of 5 mm, a slot height of 100 % produced the lowest mean deviation, This was statistically significant, when compared with 105 % (p < 0.05), 110 % (p < 0.001) and 120 % (p < 0.001).(Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of increasing slot height at 5 mm jig thickness.

| Thickness |

5 mm |

P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Slot height | Mean (Standard deviation) | |

| 100 % | 0.67 (SD 0.51) | – |

| 105 % | 1.67 (SD 0.82) | <0.05 |

| 110 % | 4.92 (SD 0.80) | <0.001 |

| 120 % | 4.5 (SD 1.41) | <0.001 |

At a jig thickness of 10 mm, there was no statistically significant difference in cutting accuracy when comparing slot heights of 100 %, 105 % (p = 0.07), or 110 % (p = 0.22). At a slot height of 120 %, there was a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in mean deviation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of increasing slot height at 10 mm jig thickness.

| Thickness |

10 mm |

P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Slot height | Mean (Standard deviation) | |

| 100 % | 0.58 (SD 0.58) | – |

| 105 % | 1.16 (SD 0.41) | 0.07 |

| 110 % | 1.25 (SD 1.13) | 0.22 |

| 120 % | 1.83 (SD 0.88) | <0.05 |

At a jig thickness of 15 mm, there was no statistically significant difference in cutting accuracy at all slot heights (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of increasing slot height at 15 mm jig thickness.

| Thickness |

15 mm |

P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Slot height | Mean (Standard deviation) | |

| 100 % | 0.42 (SD 0.49) | – |

| 105 % | 0.83 (SD 0.52) | 0.18 |

| 110 % | 0.75 (SD 0.82) | 0.41 |

| 120 % | 1.08 (SD 0.86) | 0.13 |

4. Discussion

The accuracy of bone cuts is crucial in orthopaedic surgery. In cases of tumour resection, a safe margin should obtained precisely whilst maximising the preservation of normal tissue.5 In total knee arthroplasties, inaccurate bone cuts may contribute to malalignment of the implant and in turn significant consequences such as early aseptic loosening.6 In complex anatomical regions such as the shoulder or pelvis, it is prudent to make accurate cuts to avoid damaging surrounding anatomical structures. Deviations to the intended trajectory of a cut can lead to significant consequences, such as cutting into the tumour resulting in local recurrence, or an ill-fitting implant causing poor functional outcomes.7,8 A surgical jig aims to guide the cutting tool to make accurate and reproducible cuts. Studies have shown the accuracy conferred by 3D-printed patient specific surgical jigs is similar to that of navigation.9 However, the ideal design and dimensions of 3D-printed cutting jigs have not yet been studied.

The thickness of a jig as well as its cutting slots are fundamental parameters of jig construction. If the optimal parameters are obtained, jigs that reliably produce accurate cuts can be produced easily. Studies have reported better accuracy using thicker sawblades with low slots heights. Ohmori et al. used a slot height that was 110 % of the sawblade's thickness to minimise motion between the saw and the cutting guide and achieved a cutting error of no more than 2°.10 Wong et al. used a slot height that was 120 % of the sawblade's thickness, and found using a navigation system that the planned and actual bone resection differed by less than 1 mm.11

There are challenges with the use of a thicker cutting jig however. With a thicker jig, the cutting slot will be deeper, allowing for reduced angular deviation of a sawblade and subsequently a more accurate cut, as illustrated in Fig. 7. However, thicker jigs may be difficult to use in confined spaces and smaller incisions, impinging on surrounding tissues and resulting in improper seating on anatomical landmarks. There is also increased friction with the saw, leading to heat issues and reduced manoeuvrability.

Fig. 7.

Pictorial representation showing reduced angular deviation of sawblade with a thick jig compared to a thin jig.

Secondly, a cutting slot of lower height will allow for the least amount of deviation of a sawblade, giving more accurate cuts (Fig. 8). However, it is difficult to insert a sawblade into a small slot. The saw will also be difficult to manoeuvre, and may get stuck within the slot. There is hence a delicate balance between achieving accurate cuts versus a greater useability of the jig.

Fig. 8.

Pictorial representation showing reduced angular deviation of sawblade with a cutting slot of lower height, compared to a greater height.

There is no general guideline regarding the acceptable degree of deviation when making surgical cuts. However, it has been reported that a deviation of around 3° is acceptable in studies on knee arthroplasty.12, 13, 14 An anatomical alignment outside this range of tolerance can affect patient outcomes including rehabilitation, range of motion, stability and implant durability.12 In our study, we deemed a mean deviation of more than 3° to be inaccurate.

Our study found that when using the thinnest 5 mm jig, a slot height of the exact same thickness as the sawblade (100 %) gave the most accurate cuts. However, using the next height of 105 % provided cuts with only a mean error of 1.67°, which still remains accurate by our definition, using a mean deviation of 3° as a cut-off. Although the 105 % slot is significantly less accurate than 100 %, we found it more comfortable to use, in terms of smoother insertion and movements, and also rarely getting stuck within the slot. When the slot height was further increased to 110 % and 120 %, the mean error was established to be 4.50° and greater. This is likely from the high amount of angular motion allowed during cutting due to a combination of a thin jig with a lower height slot, which will have clinically significant risks of making inaccurate cuts. Therefore, if a thin jig of 5 mm is required for surgery, we recommend the use of a 105 % slot height if cutting accuracy is not of paramount importance. Additionally, we do not recommend to increase the slot height to 110 % or greater when using a jig of 5 mm thickness.

Crucially, our study demonstrates that the overall lowest absolute mean error was achieved using the thickest jig of 15 mm in combination with the cutting slot of lowest height of 100 %. This is likely because a combination of a thick jig with a cutting slot of low height allows for the least angular motion of the sawblade. However, when the jig thickness is 15 mm, we found that there is no statistically significant difference in cutting accuracy, even when increasing the slot height to 120 % (Table 4). Additionally, at a jig thickness of 15 mm, our experience with the use of a slot of greater height of 120 % is more positive, with smoother insertion and movements, as compared with the 100 % slot, where manoeuvrability is low, leading to the occasional stuck sawblade. Hence, we recommend that if surgical space allows for a thicker jig of 15 mm, it is possible to maintain accuracy while maximising comfort and useability for the surgeon by making the slot height wider, even up to 120 % of the saw's width.

The recommendations on the optimum jig parameters for surgeons intending to design surgical jigs based on our study results are summarized below (Fig. 9). First and foremost, if a 15 mm thickness jig can be placed easily within the wound, it should be chosen as it produces the most accurate cuts. Additionally, since the slot height can be increased up to 120 % of the sawblade's thickness without a statistical significant effect on cut accuracy (Table 4), the use of a 120 % slot is recommended as it allows an additional advantage of surgeon comfort and useability. Secondly, if only a smaller jig can be used, such as 5 mm, designing a slot height of not more than 105 % is recommended, since the larger slots will produce inaccurate cuts. The choice of using a 100 % or 105 % slot size would ultimately depend on the margin of error of that the surgical procedure allows, as 100 % demonstrates statistical significance in producing more accurate cuts (Table 2), but will be difficult to use due to the tighter slot. Finally, if a 10 mm jig is chosen, a slot height of 120 % is recommended, as none of the different slot heights show superiority in accuracy that is statistically significant (Table 3).

Fig. 9.

Pictorial - Summary of recommendation.

The infrastructure to utilise 3D-printing technology is already in place in many technologically-advanced societies.15 Surgeons should take the lead to design and develop 3D-printed jigs based on the needs of their procedures, with a goal of improving surgical outcomes while at a low cost. Our team was able to fabricate the 3D-printed jigs easily in our hospital as an in-house 3D-printer was readily accessible. Furthermore, the cost price for consumables needed to manufacture the jigs was low at 50 Singapore Dollars (SGD) per jig, which is significantly more affordable than alternative technology such as navigation.4 Navigation is also only available for a selected number of procedures currently and the equipment required is more elaborate. This makes 3D-printed cutting jigs a more cost effective option to increase the accuracy of surgical cuts.

In summary, as 3D-printing technology continues to develop, we foresee the application of 3D-printed jigs in a growing number of surgeries in the future. With a greater understanding of the design and using reproducible parameters of 3D-printed jigs, surgical outcomes can be optimized with the use of the low cost 3D-printed jigs. Further studies can be performed to further explore different parameters of jig construction that can lead to greater improvements in accuracy.

5. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small number of variables investigated, as materials were limited, and obtaining multiple cuts for each single variable was prioritized to obtain more reliable results. Future larger scale studies can be undertaken to investigate whether further increasing jig thickness or changing slot heights can improve cutting accuracy further.

Secondly, due to the scarcity of cadaveric bone samples in our country, wooden blocks were used instead of human bone to make the cuts in spite of using a sawblade designed for cutting human bone. Wood was selected as its properties are more similar to that of bone than other materials such as polyurethane foam.16 However, it is possible that a bony surface, especially if irregular or curved, may result in a different degree of vibration or ease of cutting as compared to a wood surface. Future biomechanical studies with human bone should be performed to evaluate if the results are reproducible.

6. Conclusion

This study is the first to propose tangible parameters that can be applied to surgical jig construction to obtain reproducible accurate cuts. Specifically, in confined wounds whereby only a 5 mm thickness jig can be used, a cutting slot height of no greater than 110 % of the sawblade thickness must be used in order to control sawblade deviation to ensure accurate cuts. Otherwise, the use of a 15 mm thickness jig with a cutting slot height 100 % of the sawblade thickness is shown to produce the most accurate cuts overall. Additionally, unique only to 15 mm, increasing the slot height to 120 % improves surgeon comfort whilst still demonstrating reliably accurate cuts with low angles of deviation of less than 3°. The ideal surgical jig with a superior balance of accuracy and useability is therefore 15 mm thick, with a cutting slot height of 120 % of the sawblade thickness.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yiu Hin Kwan: Validation, Visualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, preparation, Writing – review & editing. Dean Owyang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Sean Wei Loong Ho: Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Michael Gui Jie Yam: Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Levesque J.N., Shah A., Ekhtiari S., Yan J.R., Thornley P., Williams D.S. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: a scoping review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5(7):430–441. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.190024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Syed S.A., Gaur B., Sagar S., et al. In: Chakrabarti A., Poovaiah R., Bokil P., Kant V., editors. vol. 223. Springer; Singapore: 2021. Guidelines to design custom 3D printed jig for orthopaedic surgery; pp. 585–594. (Design for Tomorrow—Volume 3. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wixted C.M., Peterson J.R., Kadakia R.J., Adams S.B. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4) doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yam M.G.J., Chao J.Y.Y., Leong C., Tan C.H. 3D printed patient specific customised surgical jig for reverse shoulder arthroplasty, a cost effective and accurate solution. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;21 doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2021.101503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiba H., Spazzoli B., Tsukamoto S., et al. Current concepts in the resection of bone tumors using a patient-specific three-dimensional printed cutting guide. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(4):3859–3870. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30040292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajuied A., Smith C., Carlos A., et al. Saw cut accuracy in knee arthroplasty - an experimental case-control study. J Arthritis. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.4172/2167-7921.1000144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchi G., Frisoni T., Spazzoli B., Lucchese A., Donati D. Computer assisted surgery and 3D printing in orthopaedic oncology: a lesson learned by cranio-maxillo-facial surgery. Appl Sci. 2021;11(18):8584. doi: 10.3390/app11188584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan F.A., Lipman J.D., Pearle A.D., Boland P.J., Healey J.H. Surgical technique: computer-generated custom jigs improve accuracy of wide resection of bone tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(6):2007–2016. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2769-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDessi S.J., Jang B., Harris I.A., Wheatley E., Bryant C., Chen D.B. A comparison of alignment using patient specific guides, computer navigation and conventional instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2014;21(2):406–409. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohmori T., Maeda T., Kabata T., Kajino Y., Iwai S., Tsuchiya H. The accuracy of initial bone cutting in total knee arthroplasty. Open Journal of Orthopaedics. 2015;5(10):297–304. doi: 10.4236/ojo.2015.510040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong K.C., Kumta S.M., Sze K.Y., Wong C.M. Use of a patient-specific CAD/CAM surgical jig in extremity bone tumor resection and custom prosthetic reconstruction. Comput Aided Surg. 2012;17(6):284–293. doi: 10.3109/10929088.2012.725771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardakos N.V., Lilikakis A.K. Customised jigs in primary total knee replacement. Orthop Muscular Syst. 2014;S2:7. doi: 10.4172/2161-0533.S2-007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh D., Patel K.C., Singh R.D. Achieving coronal plane alignment in total knee arthroplasty through modified preoperative planning based on long-leg radiographs: a prospective study. J Exp Orthop. 2021;8(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s40634-021-00418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yau W.P., Chiu K.Y. Cutting errors in total knee replacement: assessment by computer assisted surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(7):670–673. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shine K.M., Schlegel L., Ho M., Boyd K., Pugliese R. From the ground up: understanding the developing infrastructure and resources of 3D printing facilities in hospital-based settings. 3D Printing in Medicine. 2022;8:21. doi: 10.1186/s41205-022-00147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naylor A. Can wood be used as a bio-mechanical substitute for bone during evaluation of surgical machining tools? Bioresources. 2014;9(4):5778–5781. [Google Scholar]