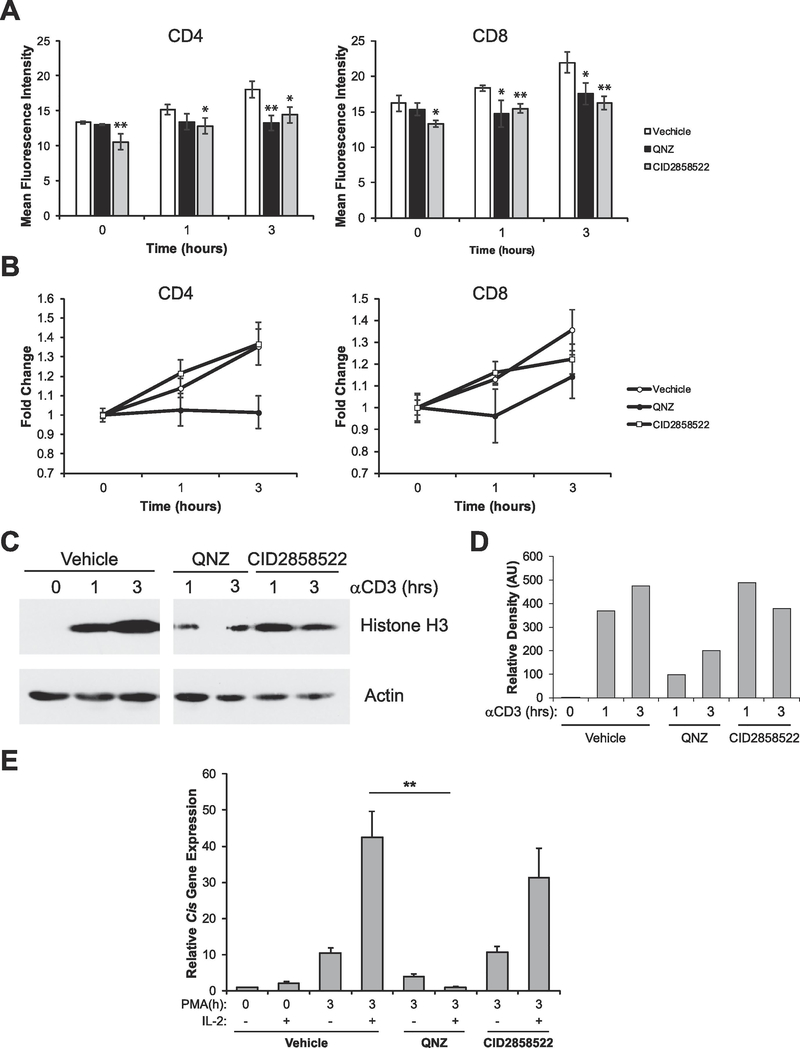

Fig. 5.

NFκB signaling contributes to activation-induced chromatin decondensation but does not contribute to acquisition of competence to respond to IL-2. (A) Splenocytes were treated with vehicle (DMSO), 100 nM QNZ, or 1 mM CID2858522 for 30 min. Cells were then stimulated with 1 μg/mL anti-CD3ε antibodies for the times indicated. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry to determine chromatin accessibility in CD4+ and CD8+ cells by intracellular staining for H3K4me1. Data are the means ± SD of triplicates and are presented as the mean fluorescence intensity of H3K4me1 staining. (B) Data from A was calibrated to the 0 h time point to show fold change in chromatin decondensation over time. (C) Sorted naïve (CD25-) T-cells were left untreated or stimulated with vehicle (DMSO), 100 nM QNZ, or 1 mM CID2858522 for 30 min. Cells were then stimulated with 1 μg/mL anti-CD3ε antibodies for the times indicated. Proteins were resolved via SDS-PAGE and histone solubility was measured via detection of histone H3 as assayed by Western blot. Detection of Actin serves as a loading control. (D) Sorted naive (CD25-) T cells were left untreated (naïve) or treated with vehicle (DMSO), 100 nM QNZ, or 1 mM CID2858522 for 30 min, then cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL PMA for the times indicated. Each sample was then divided in half and either left untreated or stimulated with 1000U/mL of IL-2 for 1 h. Total RNA was isolated and expression of the STAT5 target gene Cis was determined by qRT-PCR relative to the housekeeping gene CD3ε. All data are calibrated to the naïve 0 h control. **p < 0.001 (Student’s t-test) compared with vehicle control. All data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.