Summary

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) can mimic almost all other liver disorders. A phenotype increasingly ascribed to drugs is autoimmune-like hepatitis (ALH). This article summarises the major topics discussed at a joint International Conference held between the Drug-Induced Liver Injury consortium and the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. DI-ALH is a liver injury with laboratory and/or histological features that may be indistinguishable from those of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). Previous studies have revealed that patients with DI-ALH and those with idiopathic AIH have very similar clinical, biochemical, immunological and histological features. Differentiating DI-ALH from AIH is important as patients with DI-ALH rarely require long-term immunosuppression and the condition often resolves spontaneously after withdrawal of the implicated drug, whereas patients with AIH mostly require long-term immunosuppression. Therefore, revision of the diagnosis on long-term follow-up may be necessary in some cases. More than 40 different drugs including nitrofurantoin, methyldopa, hydralazine, minocycline, infliximab, herbal and dietary supplements (such as Khat and Tinospora cordifolia) have been implicated in DI-ALH. Understanding of DI-ALH is limited by the lack of specific markers of the disease that could allow for a precise diagnosis, while there is similarly no single feature which is diagnostic of AIH. We propose a management algorithm for patients with liver injury and an autoimmune phenotype. There is an urgent need to prospectively evaluate patients with DI-ALH systematically to enable definitive characterisation of this condition.

Keywords: Liver injury, hepatotoxicity, drug-induced liver injury, DILI, autoimmune hepatitis, AIH, DI-ALH, Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis, epidemiology, diagnosis, management, outcome

Foreword

The European Cooperation in Science & Technology (COST Action CA17112), ‘Prospective European Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network’ was established in 2018; and during a joint meeting with the International AIH Group (IAIHG) at the International Liver Congress, the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), it was decided to hold an International Expert Conference on drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH). The goals were to harmonise case definitions, revisit the approach to diagnosis, and debate the merit of interventions with immunosuppressive therapy in circumstances where a drug is suspected of causing immune-mediated liver injury resembling autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). This article summarises the major topics discussed at the Conference, in March 2022 in Nerja, close to Malaga, Spain. This meeting is expected to expand collaborations between experts in AIH and DILI, and address the identified gaps in knowledge by proposing a high-quality research programme. EASL has endorsed both the DHILI (Drug and Herbal & Dietary Supplement-Induced Liver Injury) consortium and the IAIHG as official EASL consortia. This consensus report is timely due to the growing use of biologicals in the treatment of immune-mediated diseases.

Introduction

Drugs, herbals, and dietary supplements can cause a variety of acute and chronic liver injuries in susceptible individuals, resulting in a variety of phenotypes that mimic almost all liver disorders.1 One of the phenotypes increasingly ascribed to drugs was hitherto frequently referred to as “drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis” in the literature, and will be termed “drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH)” in this article.2 ALH events are characterised by histological features highly overlapping with ‘idiopathic’ (classical) AIH and often associated with the presence of serum liver autoantibodies and elevated IgG levels.3 Currently, there are no specific pathognomonic findings or individual biomarkers that can be used to establish a diagnosis of idiopathic AIH. Diagnosis of AIH is based on clinical, biochemical, serological and histological features. These are often overlapping with those identified in patients with drug-induced ALH.4–6 Whether a given case of acute liver injury with an autoimmune phenotype is the drug-induced unmasking of subclinical AIH or de novo drug-induced liver injury (DILI) accompanied by autoimmune features may be difficult to distinguish (Box 1).7 It is notable that several drugs and vaccines - including COVID-19 vaccines more recently – have been identified as triggers for the onset of AIH.8

Box 1. Key challenges faced in detecting, assessing, and managing suspected acute DI-ALH and distinguishing it from idiopathic AIH.

The literature surrounding DILI with an autoimmune phenotype is scarce, but awareness of the condition is increasing.

There are no regulatory guidelines or society position papers that systematically address case definitions, diagnostic approaches and management in patients with suspected DI-ALH. It is difficult to differentiate between different phenotypes with certainty.

Both diagnoses are reliant on a number of overlapping clinical features. Diagnosis of DILI as well as AIH are dependent upon the systematic evaluation of clinical, laboratory and histological features. While increasing evidence points to the involvement of immune mechanisms in DILI, drugs and HDS with positive autoantibody titres exhibit a pattern of injury closely simulating AIH, presenting many or all of the features of classical AIH.

In a few patients, episodes of DILI have developed from multiple drugs (recurrent DILI) and second episodes of DILI were more likely to be associated with features of AIH.

It is plausible that drugs and vaccines can trigger AIH and yet, there are not sufficiently robustly designed studies to identify particular agents that induce such an event. For some drugs the link to DI-ALH is well documented, whereas some suspected agents are probably innocent bystanders, but the process of identifying/determining such links is dynamic.

It is unknown if DI-ALH tends to resolve spontaneously or if it can even evolve to acute liver failure as idiopathic AIH occasionally does.

Liver biochemical monitoring and stopping criteria that are utilised for patients with no underlying liver disease who develop a hepatocellular or cholestatic DILI signal in the setting of a clinical trial may not apply to those with DILI and an autoimmune phenotype.

Management of DI-ALH with immunosuppressants is controversial and not evidence-based. It is questionable how long the clinician should wait before initiating immunosuppression (usually corticosteroids) when liver tests do not improve and even worsen after the discontinuation of the implicated agent. There is no guidance on when to start immunosuppressive therapy, which dose, how long it should be maintained, or if and when it needs to be discontinued.

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; DI-ALH, drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; HDS, herbals and dietary supplements.

In contrast to a recognised high potential for chronicity or recurrence of hepatitis in AIH that requires long-term immunosuppressive therapy, ALH often resolves or improves upon withdrawal of the offending drug. Nonetheless, some patients with ALH may develop acute liver failure (ALF) or clinically significant chronic injury for whom long-term clinical follow-up may be warranted. Currently, there are no predictive markers that identify such individuals. With high rates of lasting resolution of liver injury in most patients with ALH after drug discontinuation, optimal management and requirement of immunosuppressants for this condition have yet to be elucidated. Defining optimal treatment regimens, including duration and dosage protocols, for the management of ALH remains an unmet challenge. Optimising such practices could reduce the risk of adverse effects from immunosuppressive medications and associated healthcare costs.9

The International AIH Group (IAIHG) has sought to improve methods for the diagnosis and management of AIH and AIH-related conditions.5 In partnership, the Prospective European Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network10 and the IAIHG convened a conference to establish a consensus for standardised nomenclature surrounding drug-induced ALH, to determine best practices in management and to identify key requirements of new diagnostic and mechanistic biomarkers. This article provides an overview of the major topics that were discussed at the workshop, including an assessment of currently used terminologies, management strategies, and future directions for research.

Terminology, case definition and phenotypic presentation

AIH is thought to be caused by a loss of immunological tolerance in liver tissue resulting in immune-mediated damage of the hepatic parenchyma.6,11,12 In genetically predisposed individuals, environmental factors, such as infections, are thought to initiate the self-perpetuating disease, but a definitive trigger has not been identified.5,6,12

Idiosyncratic DILI affects only susceptible individuals and is less related to the drug dose.13 Since idiosyncratic DILI can, albeit rarely, manifest with clinical, biochemical, immunological, and histological features resembling the phenotype of AIH, the two entities must be distinguished. Four terms denoting such a DILI phenotype have been used in the published literature: “drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis (DI-AIH)”,14–18 “immune-mediated DILI”,19 “drug-induced liver injury with autoimmune features”20 and “drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH)”.4,21

Nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for DI-ALH lack specificity. There is compelling evidence that idiosyncratic DILI is typically an immune-mediated disorder. The term “immune-mediated DILI” is also associated with many drugs that are not associated with well recognised autoimmune features.19,22,23

Because autoantibodies can be found in many other liver disorders, DILI with “autoimmune features” is a descriptive and non-specific term. For these reasons, DI-ALH4 was chosen by many experts as the preferred term to specifically denote this condition. In the literature, DI-ALH is referred to as liver injury with laboratory and/or histological evidence of autoimmunity, high IgG levels, positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody. The liver damage in DI-ALH usually manifests clinically within 3 months of drug exposure, but can appear after more prolonged latency.14,15,19,21,24 The majority of DI-ALH cases present with an acute hepatocellular injury pattern but in rare instances a cholestatic pattern is observed.21 Evidence of features of hypersensitivity like eosinophilia, fever, or rash are usually absent (Table 1). DI-ALH has been well documented for minocycline, nitrofurantoin, hydralazine, methyldopa, interferon, imatinib, adalimumab and infliximab.21,24 After withdrawal of the causal drug, the liver injury resolves in the vast majority,14,21 either spontaneously within 6 months or with corticosteroids.14,21 The lack of a reliable diagnostic biomarker and evidence-based treatment paradigm has resulted in limited guidance on how to manage this aspect of DILI.2,5,6,25–27

Table 1.

Summary of case series of patients with DI-ALH and response to treatment.

| Observational studies | Björnsson 201014 | Ghabril 201335 | Rodrig. | De Boer 201724 | Björnsson | Björnsson | García-Cortés |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 24) | (n = 6) | 201534 (n = 8) | (n = 88) | 201717 (n = 15) | 202250 (n = 36) | 202351 (n = 33) | |

| Drugs implicated (number of patients) | Nitrourantoin (10) Minocycline (10) Cephalexin (1) Prometrium (1) |

Infliximab (3) Etanercept(2) Adalimumab |

Infliximab (7) Adalimumab |

Nitrofurantoin (42) Minocycline (28) Methyldopa (10) Hydralazine (7) |

Infliximab (10) Nitrofurantoin (3) Imatinib |

Infliximab (31) | Statins (8) Nitrofurantoin (5) Minocycline (4) Amox-Clav (2) Cyproterone (2) Others (11) |

| Age (years), median (range) | 53 (24–61)¥ | 35 (28–54) | 40 (34–69) | Nitrofurantoin 65 (36–84) Minocycline 19 (16–61) Methyldopa 29 (18–43) Hydralazine 60 (42–76) |

55 (20–91) | 46 (32–54)¥ | Mean 53 (15–86) |

| Females % | 92% | 83% | 63% | 91% | 93% | 78% | 58% |

| Autoimmune comorbidities, % | — | 100% | 100% | — | 73% | — | 27% |

| Acute onset, % | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Treatment duration (days), median (range) | — | — | — | — | 116 (84–1,320) | — | 92 (40–312)¥ |

| Time to onset (days), median (range) | — | 112 (14–364) | — | 277 (8–7,032) 100 (13–1572)* |

— | 110 (94–144)¥ | 94 (42–255)¥ |

| Jaundice, % | 50% | 50% | — | 59% | 53% | 11% | 58% |

| Type of liver injury, % | — | HC: 83% Mix: 17% Chol: 0% |

— | HC: 74% Mix: 17% Chol: 9% |

HC: 93% Mix: 7% Chol: 0% |

HC: 64% Mix: 33% Chol: 3% |

HC: 84% Mix: 9.7% Chol: 6.3% |

| Hypersensivity features, % | — | Fever: 16% | — | Fever: 25% Rash: 26%. At least two features: 17% |

— | No fever, no rash | Fever: 6% Rash: 3% |

| % with peripheral eosinophilia | — | 0% | — | 4.5% | — | 8% | 18% |

| % with autoimmune features | 100% | 50% | 100% | 72% | 93% | 69% | 100% |

| High IgG values, % | 90% | — | 75% | 39% | 40% | 17% | 58%† |

| Corticosteroids: dose/duration | 20–40 mg × 8 weeks | — | — | — | 20–40 mg × 8 weeks | 20–40 mg × 8 weeks | — |

| Response to suspension of drug and | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| steroids (number) | Spontaneous (14) | Spontaneous (1) | Steroids (8) | Spontaneous (47) | Spontaneous (6) | Spontaneous (19) | Spontaneous (13) |

| Steroids (12) | Steroids (5) | Steroids (41) | Steroids (9) | Steroids (17) | Steroids (20) | ||

| Relapse after corticosteroid withdrawal | 0% | 0% | 0% | — | 0% | 0% | 12% |

| Cirrhosis at presentation | 0% | 16% | 13% | 4.5%, at follow-up | 0% | — | 6% |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis. Amox/Clav, amoxicillin/clavulanate; Chol, cholestatic; HC, hepatocellular; Mix, mixed.

Patients with and without autoimmune features, respectively.

Based on available data.

Interquartile range (IQR).

Epidemiology

Idiopathic AIH is characterised by a chronic progressive course resulting in fibrosis, liver failure and death if left untreated.28 A recent meta-analysis shows a pooled worldwide annual incidence and prevalence of AIH of 1.37 and 17.4 per 100,000 persons.29 In prospective studies, the crude incidence of DILI was estimated to be 14–19 cases per 100,000 inhabitants annually, respectively.30,31 Among 261 patients with AIH, 24 (9.2%) were diagnosed retrospectively as cases of DI-ALH.17 Among DILI cohorts, 3–8.8% can be classified as DI-ALH cases.18,24,32 In the Spanish DILI Registry, 1.2% of patients had two DILI episodes caused by different drugs, and these patients were more likely to present with autoimmune features in the second episode.7

Drugs linked to DI-ALH

More than 40 different agents have been implicated in the development of ALH.3 Metabolites from dihydralazine and tienilic acid coupled with cellular proteins can form neoantigens4 inducing immune reactions and causing DI-ALH.18,33 A summary of drugs suspected of causing DI-ALH is presented in Table 2. Previous studies comparing patients with DI-ALH to those with AIH found similar clinical, biochemical, immunological, and histological features, with the exception of cirrhosis being less common in the DI-ALH group, and no recurrence after discontinuation of immunosuppression.14 Several studies have observed the absence of relapse in patients with DI-ALH,14,17,34,35 whereas the vast majority of patients with AIH relapse after stopping immunosuppressive therapy.36 Minocycline, nitrofurantoin, methyldopa, and infliximab are the most commonly implicated drugs,4,14,24,32,37 alongside emerging reports of vaccine-induced immune hepatitis.8 Other reported causative agents of DI-ALH include interferon, statins, methylprednisolone, adalimumab, imatinib, diclofenac, Tinospora cordifolia and Khat.21

Table 2.

A summary of drugs suspected of causing DILI.

| Highly probable drug and HDS association (n = 18) | Possible drug association (n = 4) | Reported but unproven (n = 21) | Reported only in the 1970s and 1980s (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrofurantoin14 | Etanercept21 | Cephalexin14 | Halothane4 |

| Minocycline14 | Efalizumab21 | Clometacine4 | Tienilic cacid4 |

| Methyldopa20 | Atovaquone/Proguanil84 | Echinacea4 | Oxiphensation4 |

| Hydralazine20 | Turmeric21 | Pemoline4 | Sulfonamide4 |

| Infliximab35 | Ma Huang21 | Propylthiouracil4 | |

| Interferon-α & β 21 | Prometrium14 | Isoniazid4 | |

| Atorvastatin20 | Hydroxycut4 | Dantrolene4 | |

| Simvastatin20 | Meloxicam4 | Perhexiline maleate4 | |

| Fluvastatin20 | Methotrexate4 | Amiodarone4 | |

| Rosuvastatin20 | N-Nitroso-fenfluramine4 | Papaverine4 | |

| Imatinib21 | Ambrisentan4 | Benzarone4 | |

| Masitinib21 | Glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate4 | Terbinafine4 | |

| Adalimumab21 | Camostat/benzbromarone4 | Methylphenidate4 | |

| Diclofenac21 | Xiang-tian-guo4 | Bupropion4 | |

| Methylprednisolone21 | Indometacin4 | Olmesartan4 | |

| Cyproterone4 | Varenicline21 | ||

| Khat21 | Menotrophin21 | ||

| Tinospora cordifola21,83 | Indometacin4 | ||

| Fenofibrate4 | |||

| Pazopanib4 | |||

| Phenprocoumon4 |

Drugs with well documented DI-ALH (strong association), with convincing reports, that have been analysed and undergone causality assessment; possible DI-ALH with several reports that suggest a relationship but do not fulfil criteria proposed in a recent paper on DI-ALH,24 those that have been reported, mostly in single reports, with short follow-up and/or important clinical information lacking. Finally, drugs suspected to have induced DI-ALH but only in the 1970s and 1980s, before the detection of hepatitis C and with competing causes often not excluded. References are in parentheses.

Checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury

Checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury (ChILI) is accounting for an increasing proportion of recent DILI cohort studies.10,38 The pattern of injury is hepatocellular in around 60% of cases, though checkpoint inhibitor therapy-related cholangiopathy with progression to bile duct loss has also been reported.39

In a retrospective study comparing the serological profile of ChILI cases with AIH, 94% of ChILI cases had normal IgG. ANA and ASMA positivity was detected in both conditions, but was more common in AIH (84%) than in ChILI (32%).40 Liver biopsy can improve diagnostic certainty as well as avoid unnecessary immunosuppression in a proportion of cases. In 11% of patients with suspected ChILI, histology suggested an alternative pathology, such as malignancy or DILI due to another concomitant drug.41 ChILI shows less severe confluent necrosis and plasma cell infiltration, fewer CD4+ and more CD8+ infiltrating lymphocytes than classical AIH on liver biopsies.42 Consistent with current practice, steroids were administered in 59% of patients before performing a liver biopsy according to clinical guidelines, but some patients’ conditions improved without the need for immunosuppression.38,43

Autoimmune-like hepatitis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Shortly after vaccination campaigns started, the first case of possible AIH related to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was published.44 Several case reports and case series followed, with an autoimmune phenotype observed in all cases.45 Liver tests showed a hepatocellular pattern in the vast majority of cases (84%). Most affected patients were females (63%) and liver disease was diagnosed a median of 15 days after vaccination.45 The liver injury was symptomatic in most patients, with a single patient evolving to ALF requiring a liver transplantation. An immune phenotype, as defined by positivity for autoantibodies and elevated IgG levels, was detected in 57% of cases. Overall, 75% tested positive for ANA, while polyreactive IgG with reactivity against BSA/HIP1R (a new biomarker for AIH with a reportedly higher specificity than conventional autoantibodies) was detected in almost half of patients.8 Histology showed lobular hepatitis (76%) and portal hepatitis (17%), with fibrosis being more prominent in the latter, which favoured the diagnosis of DI-ALH rather than AIH, despite the fact that 82% of patients had typical or probable AIH on simplified IAIHG scoring46 and that 92% of patients had likely or possible AIH based on the ERN histology system.3 The majority of patients received immunosuppression with steroids, and liver enzymes normalised in two-thirds after 6 months. The vast majority of cases did not experience a relapse of liver injury, although follow-up was not prolonged in many cases. This is consistent with a DI-ALH phenotype, rather than an unmasking of genuine AIH. The temporal relationship between vaccination and the appearance of the liver injury, and the fact that hepatitis was diagnosed after the 2nd vaccine dose in the majority of cases8 suggested causality. In contrast, relapse of liver injury after a new dose of vaccine occurred in only 25% of cases, which challenges the causal relationship or reflects adaptation to the vaccine.8

Clinical phenotypes

A frequent challenge is to differentiate the clinical presentation of DILI from AIH, since there is no differentiating biomarker between the two entities.47 In a recent study,21 five criteria were proposed to define DI-ALH based on cases of suspected DI-ALH published in the literature. Histological characteristics do not seem to enable distinction between these entities.14,16,17 Whilst a greater degree of fibrosis has been reported in AIH,14,16,48 this may be a reflection of disease chronicity rather than reflective of aetiology.

Different case series of patients with DI-ALH describing the response to immunosuppressant therapy are presented in Table 1. Corticosteroid responsiveness was similar in both the DI-ALH and AIH groups.14 Discontinuation of immunosuppression was successful in all DI-ALH cases, whereas 65% of patients with AIH had a relapse after withdrawal of immunosuppression,14 as observed in other studies.34,35 No relapses were observed after short-term immunosuppression in the studies by Rodrigues et al. (infliximab and adalimumab)34 and by Björnsson et al. (infliximab).49,50 Interestingly, in the recent analysis of DI-ALH in the Spanish and the Latin-American registries, the probability of a relapse in patients grouped as having DI-ALH increased with time, being 17% at 6 months and 50% after 4 years of follow-up after remission.51 In a retrospective longitudinal cohort of patients with drug-induced jaundice (n = 685), 3.4% (n = 23) of patients were hospitalised (during a mean follow-up of 10 years) of whom 22% (n = 5) developed AIH at 1.5 months to 6 years from the initial event and another five developed cryptogenic cirrhosis.52 This highlights the challenges of distinguishing between DI-ALH and AIH, as well as providing evidence for the potential chronicity of DI-ALH and therefore the need for long-term follow-up.

Diagnosis

Differentiating DI-ALH from AIH is crucial since most published studies suggest that DI-ALH often resolves spontaneously after withdrawal of the causative drug and affected patients rarely require long-term immunosuppression. Timing of the diagnosis is critical for the management of both DI-ALH and AIH. Failure or late diagnosis in both cases can result in poor clinical outcomes.24

Autoantibodies

ANA and other autoantibodies are frequently associated with DI-ALH. A limitation in using ANA and ASMA is their variability among different populations, since they are absent or present at lower frequencies in some ethnicities.53 ANA and ASMA positivity is common in the general population, particularly in older individuals.54 Low ANA and ASMA titres are present in 40–65% of patients with extrahepatic autoimmunity, in the absence of liver disease.55 The presence of autoantibodies in DI-ALH is usually related to specific drug types such as methyldopa, hydralazine, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, statins and infliximab.19,56 Autoantibodies are frequently present in DILI, regardless of the causative drug.57,58 Therefore, the presence of ANA might, at least in some patients, represent an epiphenomenon of the acute DILI episode, rather than constituting a specific disease entity or DILI phenotype. Table 3 shows the prevalence of these autoantibodies in the healthy population compared to their prevalence in patients diagnosed with AIH. This evidence also highlights the limitations of these markers in distinguishing DI-ALH from AIH.

Table 3.

Proportion of patients with AIH with positive autoantibodies compared with their prevalence among healthy population.

| Test: antibodies | % positive in AIH cases | % positive in ‘normal’ population |

|---|---|---|

| ANA 1:60 | 68%–75% | 15% (<40 ♀) – 24% (>40 ♀) |

| ASMA | 52%–59% | Up to 43% |

| IgG >1,600 mg/dl | 86% | 5% |

| Anti-LKM | 4%–20% | 1% |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; anti-LKM, anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody; ASMA, anti-smooth muscle antibody; DILI, drug-induced liver injury. Adapted from reference 2.

Liver biopsy

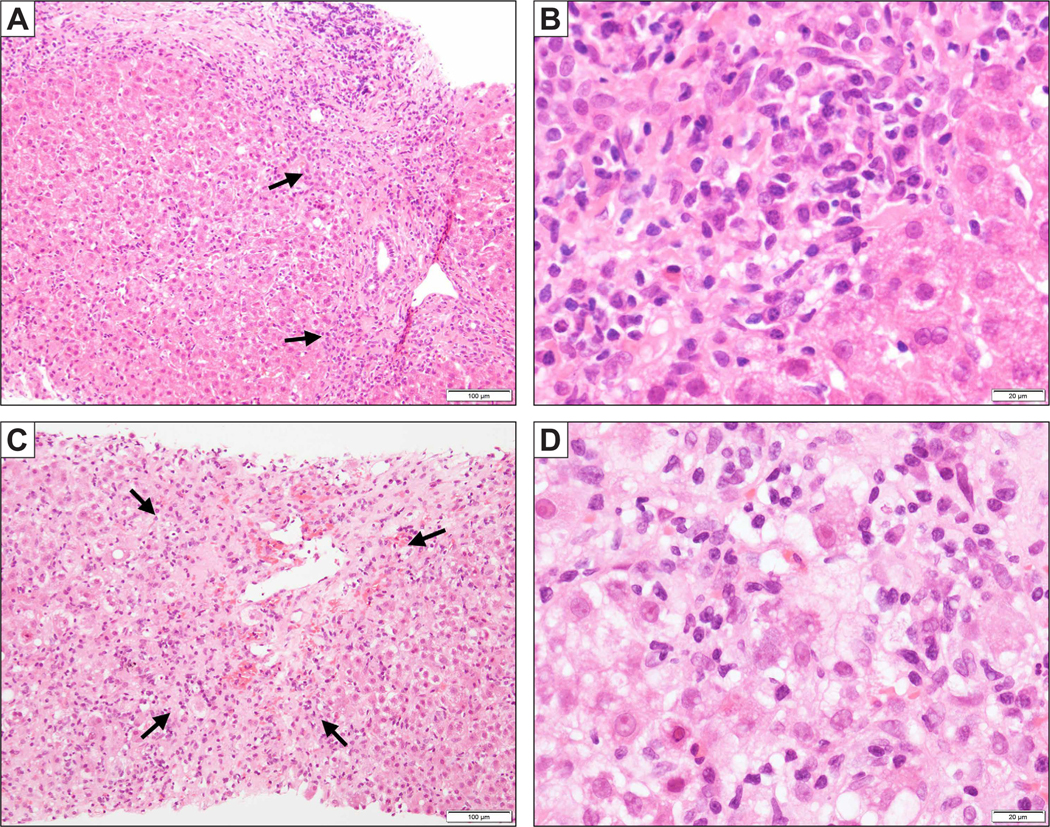

Liver biopsy has been recommended as a diagnostic test when DI-ALH is suspected, if AIH remains a competing aetiology46,59 and if immunosuppressive therapy is being considered.4,19 Liver biopsy is useful for confirmation of AIH-like histology and exclusion of other potential diagnoses (e.g., steatohepatitis). Histological features of AIH are infiltration with lymphocytes and plasma cells, interface hepatitis, rosette formation and emperipolesis.60 The specificity of emperipolesis and rosette formation for AIH has been questioned and might reflect disease severity rather than aetiology of liver injury.3 DI-ALH mimics the morphological pattern of AIH, including the prominent lympho-plasmocytic infiltrates in portal spaces and interface hepatitis.16 The parenchyma is also inflamed, and variable degrees of confluent necrosis (e.g., perivenular or panacinar necrosis) can occur. The spectrum of injury is variable and plasma cells are only increased in two-thirds of biopsies, while either an acute- or chronic-hepatitis pattern of injury can develop (Fig. 1). A limited number of studies comparing liver histology between DI-ALH and AIH have been undertaken.14,17,48 The microscopic findings that might help to discriminate between the two conditions are largely unknown, except for advanced fibrosis (i.e., cirrhosis), which is observed only in AIH, but not DI-ALH.14,16,48 Thus, liver injury associated with DI-ALH is clinically and histologically indistinguishable from that linked to AIH. Thus far, studies comparing DILI with AIH have included DILI cases more broadly and have not focused on the comparison between AIH and DI-ALH.61

Fig. 1. Liver biopsy findings in DI-ALH.

(A) A biopsy of minocycline-related DI-ALH shows a chronic hepatitis pattern of injury with predominantly portal based inflammation and periportal fibrosis. Interface hepatitis is noted (arrows). (B) Higher magnification shows plasma cells aggregated at the interface. (C) A biopsy of nitrofurantoin-related DI-ALH demonstrates an acute hepatitis pattern of injury with predominantly lobular inflammation and perivenular confluent necrosis (arrow). (D) High magnification shows enlarged hepatocytes with cytoplasmic vacuolation, multinucleation and emperipolesis, against the background of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. DI-ALH, drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis.

DILI causality assessment methods

Among the causality assessment methods used for the diagnosis of DILI, Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) has previously been the most used in clinical research worldwide.62 However, concerns have been raised regarding its poor reliability, validity and the lack of clinical evidence for the domain criteria.63 Recently, a revised electronic version of RUCAM was developed, coined the Revised Electronic Causality Assessment Method (RECAM), using data from two large prospective DILI registries, the DILIN (Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network) and the Spanish DILI Registry.64 RECAM seems to lead to improved case identification, earlier diagnosis, and medical management of DILI cases.64 However, RECAM, like RUCAM, was not designed to consider specific emerging phenotypes like DI-ALH. The original IAIHG scoring system59 was initially developed to define cohorts of patients with AIH for clinical trials and in difficult cases, but the new simplified version is more applicable to clinical practice.60 The use of the IAIHG scoring system57 in patients with DI-ALH should be further evaluated and compared with the new simplified criteria.60

New biomarkers and approaches

The use of autoantibody profiling has been explored to investigate and develop diagnostic tests that may help distinguish DI-ALH from AIH. Lammert et al., demonstrated that AIH was characterised by a group of both IgG and IgM autoantibodies while DI-ALH was only characterised by IgM, which could be used as a feature to distinguish DI-ALH from AIH.63 Four IgM autoantibodies directed at double-stranded DNA (SCL-70, ssDNA, U1-snRNP-BB) were able to differentiate DI-ALH from DILI (AUC 0.87).65 This study was limited by less than strict criteria for DI-ALH and the fact that the implicated drugs were not definitively associated with DILI with autoimmune features. In another study by Taubert et al., protein microarrays were used to identify polyreactive IgG, which is elevated in AIH.66 According to the authors, polyreactive lgG might be a new marker that could facilitate diagnosis and help to preselect patients with liver disease for biopsy, because of higher specificity and overall accuracy than routine autoantibodies (e.g. ANA, SMA, and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibodies).66

Management and treatment of DI-ALH

Information is scarce on the management of DI-ALH and comes mainly from retrospective studies. Treatment decisions are often based on experience gained from case reports or expert opinion.14,16,34,35,48,50,51 The most important initial step in terms of management of any suspected case of DILI is to discontinue the implicated agent. Delays in withdrawal of the suspected drug may impact both the severity of injury and responsiveness to therapy. Published DI-ALH cases reported high rates of spontaneous recovery after discontinuation. Resolution may not appear immediately and ongoing or even worsening liver injury can occur despite the withdrawal of the implicated drug.24,50 The type of liver injury should be assessed because steroid therapy may be necessary in the case of persistent hepatocellular or mixed type liver injury.47

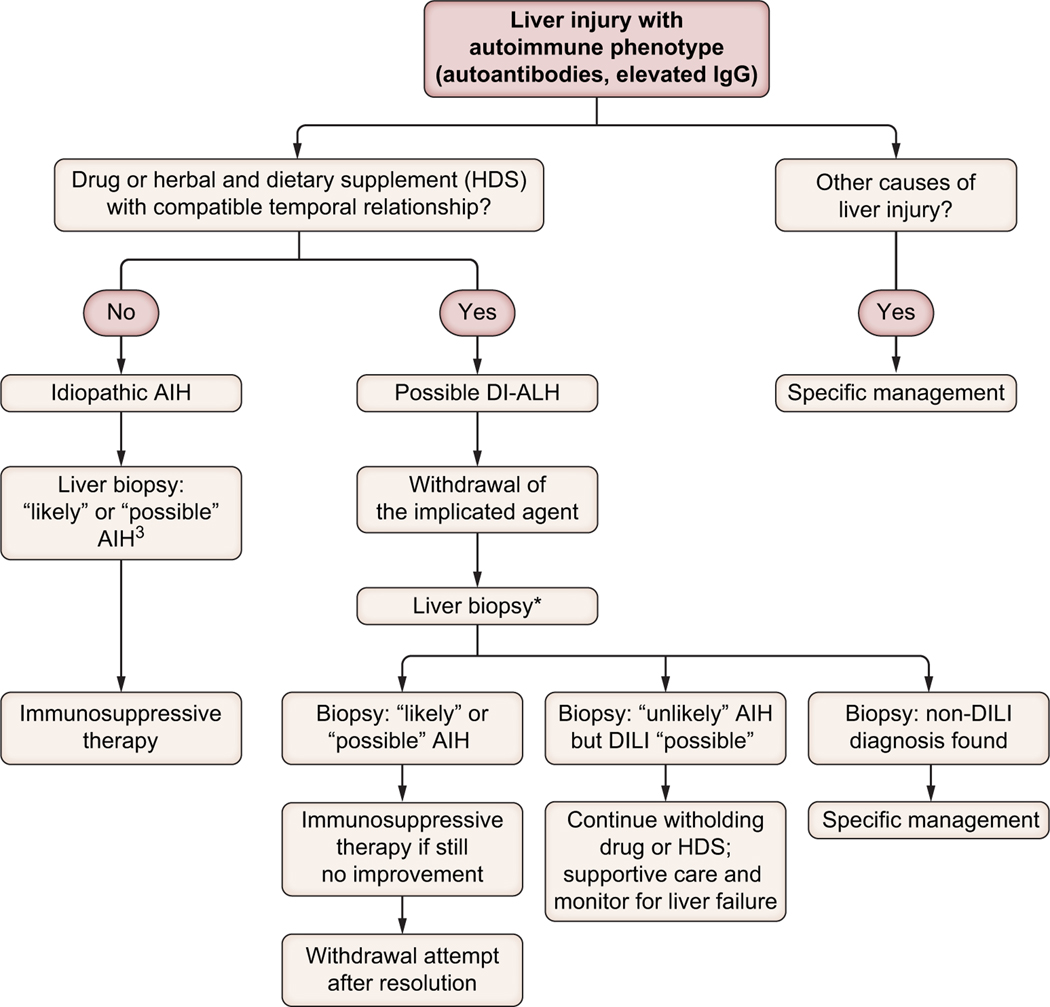

A management algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 3. EASL guidelines suggest that a multidisciplinary approach that considers the patient’s clinical and histological features should be followed when deciding on whether to initiate steroid treatment.2 Patients with suspected DI-ALH should undergo detailed evaluation including a liver biopsy in most cases. Concerning histology, the validation cohort of the new simplified criteria did not include patients with DI-ALH.46 It is not clear if the results of histology, lack of improvement of liver tests after stopping the implicated drug or both should be used as the indication for corticosteroids in patients with DI-ALH. An international collaborative study of all DILI cases retrieved from two prospective DILI registries using propensity score-matching analysis found that the benefit from steroid therapy (increase in the normalisation rate of liver biochemistry) was more evident in patients with severe DILI (nR-based Hy’s law) without disease resolution within 30 days of stopping the implicated drug.67

Fig. 3. An algorithm to approach suspected DI-ALH in clinical practice.

*Alternatively, in mild cases associated with specific drugs known to induce this phenotype (i.e. infliximab), which show clinical/biochemical improvement following drug withdrawal, a liver biopsy is not always necessary. DI-ALH, drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis.

Although corticosteroids are often used to treat DI-ALH,68 the decision to institute corticosteroid therapy should ideally be individualised.69 Corticosteroids should be used in symptomatic patients if there is no improvement or worsening in liver tests after stopping the implicated agent. A short course of corticosteroids (1–2 months) could be considered in cases of protracted or increasing abnormalities in aminotransferases.21 It is not clear how long the clinician should wait for improvement and this is currently based on clinical judgment. Corticosteroids may also be considered when rapid improvement in liver tests is desired in order to substitute the offending agent with an alternative drug.50 Recovery time was reported to be longer for DI-ALH than for DILI (8–10 weeks vs. 5–7 weeks, p <0.05).70 However, the response to immunosuppressive treatment was found to be significantly faster in patients with DI-ALH than in those with AIH (2 months vs. 16.8 months).71 A faster response or decrease in serum ALT within 1 week after initiation of corticosteroid treatment was observed in patients with DILI compared to those with AIH.72 There is very limited data on the dose of corticosteroids used to treat DI-ALH in the published literature.17,31,32,34,35 In a recent study of patients with DI-ALH associated with infliximab, the median dose of prednisolone used was 30 mg, or 40 mg for patients with jaundice.50 While different studies have reported distinct protocols and doses of steroids in AIH, there are still some uncertainties about the optimal management of these patients. Different authors agree that further work is still required to determine the optimal steroid induction protocol in patients with severe AIH.73 In the case of DI-ALH, steroid dosage is usually determined based on the principal investigator’s personal experience.74

Rechallenge (re-administration of a drug suspected to have caused DILI) is currently the strongest proof of causality in the adjudication process of suspected DILI. However, drug rechallenge in DILI cases is potentially dangerous2,75 and is associated with risk of death or requirement for liver transplant.2,15,76 Despite the known risks, positive rechallenge can be considered if the patient has shown important benefits from the drug and other options are not available.76 The definition of positive rechallenge is currently defined as alanine transaminase (ALT) levels >3–5x the upper limit of normal after re-administration of the suspect drug, in a patient with normal baseline ALT.75 Information about positive or negative rechallenges in DI-ALH is very limited and restricted to individual cases. Therefore, additional data are needed from controlled clinical trials, prospective registries, and large health care databases.

Natural history

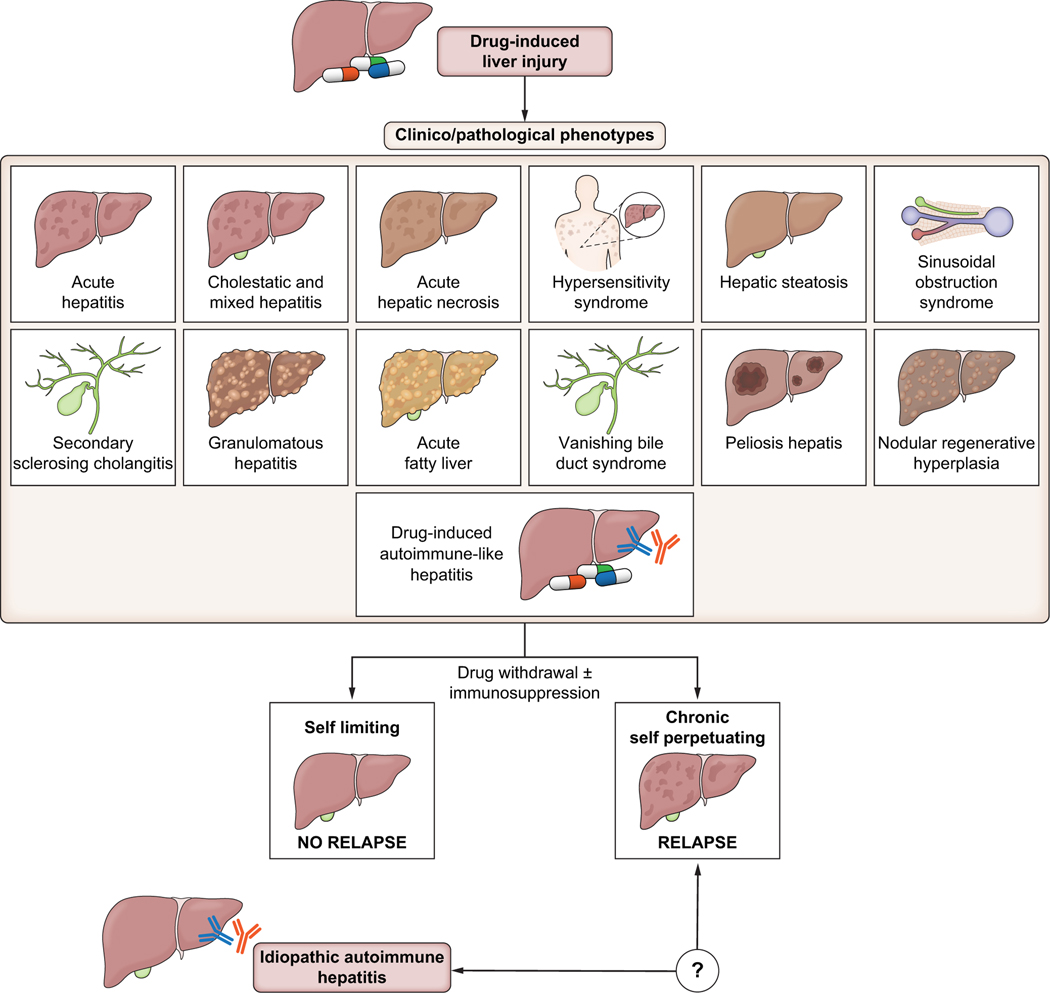

After the withdrawal of the causative agent and with institution of immunosuppression, the outcome in DI-ALH is generally good in most cases, with a low risk of relapse or progression to chronic liver injury, as reported in different studies with heterogeneous follow-up (Table 1).14,17,34,35,50 Interestingly, however, in a long-term follow-up of DI-ALH cases collected in two prospective DILI registries, the likelihood of relapse increased over time, reaching 50% after more than 4 years of follow-up.51 Thus, DI-AHL presents as a “self-limited” phenotype that resolves or becomes quiescent when the drug is removed, but in some cases, liver injury does progress to chronicity and a “self-perpetuating” autoimmune liver disease ensues (Fig. 2).22,51,52

Fig. 2. Overlap between drug-induced liver injury, drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis, and idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis.

Limited number of patients with drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis progress to chronicity and evolve a disease phenotype more like that of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis.

Normalisation of liver tests, either spontaneously or after the use of immunosuppression, in patients with DILI does not always guarantee a benign course, highlighting the need for prolonged follow-up in case of AIH development after the resolution of DILI.52,77 Additionally, early identification of patients with DI-ALH who might progress to ALF is still challenging.78 An algorithm developed by the Spanish DILI Registry to identify patients at higher risk of ALF at DILI recognition showed 82% specificity and 80% sensitivity.79 However, this has not been replicated and it is unknown if this algorithm applies to DI-ALH.

Implications for drug development

DILI is a major cause of the withdrawal of potentially valuable therapies post-marketing.80 Current methods have not been shown to be helpful in predicting DILI or DI-ALH in clinical studies.81 Due to the lack of effective biomarkers, Hy’s law is currently the most used tool to assess a drug’s potential to cause severe DILI. Therefore, the most specific indicator that a drug is hepatotoxic is the occurrence of drug-induced hepatocellular injury with jaundice, and/or an increased international normalised ratio.82 Labelling cases as potential DI-ALH in clinical trials may trigger follow-up actions, including: determining liver-specific autoantibodies in patients with elevated aminotransferases, administering steroids according to current recommendations for treatment of AIH, and long-term follow-up of study participants to monitor for possible flares of AIH in either the presence or absence of study drug. For this reason, caution should be exercised in classifying a case of suspected DILI as DI-ALH, since this can have a profound impact on the workup of these patients, the decision to interrupt or discontinue treatment and the overall safety assessment of the developmental compound. A comprehensive identification of potential DI-AILH cases in clinical studies would require a dedicated initiative, for instance in the frame of a public-private partnership that specifically addresses this question and allows partner companies to share samples and data.

A much better understanding of the mechanisms underlying DILI and DI-ALH is essential to design improved predictive models.82 Thus, future research should focus on applying new technological advances and constructing a systematic biological approach to understand the mechanism and identify initial pathways. This will enable the identification of new treatment targets and other environmental and genetic factors that also have a profound impact on the risk of an individual patient developing overt liver disease. This would allow physicians to stratify patients according to their environmental and genetic factors and to adopt a personalised approach to the treatment of DI-ALH.

Current gaps and future directions to improve the analysis and management of DI-ALH

Several gaps were identified in terms of clinical diagnosis and management, which would benefit from future research on the mechanisms of prevention and treatment of DI-ALH. The participants reached a consensus regarding existing gaps in the field that should prompt more research.

To define the precise epidemiology of DI-ALH, a correct diagnosis of the (auto)immune phenotype of DILI is necessary. Comprehensive identification of potential DI-ALH cases in clinical studies will require a dedicated initiative, preferably including prospective studies that specifically address this question and allow for partner companies to share samples and data.

The use of a consensus definition of DI-ALH will enable analyses of larger populations based on the same criteria, helping to define the different classes of drugs/agents that can cause DI-ALH as an entity and guiding outcome prediction and patient management.

There is a lack of data and specific biomarkers to characterise and discriminate DILI vs. AIH vs. DI-ALH. It is imperative to improve liver histology evaluation to better characterise the patterns of DI-ALH. The experts agree on the need to develop a tool for diagnosing DI-ALH before the initiation of therapy.

A systematic investigation of the type and pattern of autoantibodies detected in DI-ALH, adhering to dedicated methodological guidelines, with comparison to AIH is warranted to investigate whether they can serve as specific biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and response to treatment.

The experts agree that information on the morphologic evaluation of liver biopsy can be augmented by using immunohistochemical and molecular techniques. Future studies incorporating immune cell phenotyping may help identify immunohistochemical markers useful for the diagnosis of DI-ALH. A properly designed biopsy study and the discovery of new molecular markers may help to provide clarity on the differences between DI-ALH and AIH.

Testing for carriage of particular HLA alleles in selected cases will assist in the diagnosis of DILI or AIH. Further studies are needed to clarify the genetic heterogeneity and pathogenesis of AIH and DI-ALH. Moreover, there is a clear need to evaluate the use and effectiveness of genetic tests for the diagnosis of AIH vs. DI-ALH and for decision-making in this clinical context.

The current identified gaps in the management of DI-AILH are: 1) which patients require immunosuppression, 2) standardisation of treatment regimens (e.g. dose and duration of therapy) in the event immunosuppression is administered, and 3) when to withdraw therapy. Thus, a set of criteria for DI-ALH assessment including tests and follow-up that should be performed in prospective studies was generated during the workshop (Table 4).

A prospective assessment of predictors of positive rechallenge, with the same or with a different drug, and outcomes should be performed.

Conducting spatial profiling of gene signatures on liver biopsies should help to highlight the differences between DI-ALH and AIH, allowing for future fine-tuning of nomenclature. Future research involving comparative analysis using distinct “omics” technologies may enable the categorisation of DI-ALH cases, allowing us to better predict their progression, spontaneous resolution, response to therapy and outcomes.

The experts agreed that larger prospective studies with relevant follow-up information on immunosuppression are needed to properly characterise the natural history of DI-ALH. Moreover, since the progression of DI-ALH to ALF is uncommon, and there are no biomarkers predictive of disease progression, the experts recommend that patients with an acute severe presentation should be referred and managed in centres with advanced hepatology care.

Table 4.

Recommended data for proper assessement of a suspected case of drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis.

| Basic assessment criteria | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | • Age, sex, weight, BMI, ethnicity |

| Clinical data | • Comorbid conditions, autoimmune disorders, underlying liver disease (e.g. steatosis) • Toxic habits: alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, over the counter drugs • Type of liver injury (aminotransferases, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase) • Signs and symptoms: jaundice, hypersensitivity features (rash, peripheral eosinophilia, lymphopenia), encephalopathy, ascites, hospitalisation |

| Drug exposure history | • Take a thorough pharmacological history with exposure to drugs/vaccines/herbal remedies with doses and start-stop dates • Excluded exposure to immune-checkpoint inhibitors |

| Temporal relationship* | • Treatment duration, days • Latency, days |

| Meet criteria definition for DILI | • ALT exceeding 5x ULN • ALP exceeding 2x ULN • ALT exceeding 3x ULN and bilirubin exceeding 2x ULN |

| Exclusion of alternative diagnoses# | • Viral hepatitis A, B, C, and E, biliary obstruction, AIH, alcohol-related hepatitis, ischaemic hepatitis, malignancy |

| Biochemical parameters¶ | • Liver profile at onset, on remission, when worsening, relapse (ALT, AST, ALP, total bilirubin, INR) • Autoantibodies: ANA, ASMA with pattern on kidney tissue, Anti-LKM1, anti-SLA/LP • IgG levels |

| Histological features | Date. Description of the following features recommended: • Pattern of injury (portal or lobular based hepatitis) • Degree of necroinflammatory changes and fibrosis according to Ishak’s grading and staging system85 • Plasma cell infiltration or clusters. • Documentation of other histological features of significance: hepatocellular or canalicular cholestasis, chronic cholestasis changes, eosinophils, confluent necrosis, steatosis, vascular injury) • Exclusion of other diseases (e.g., steatohepatitis, cholangiopathy) • Overall assessment based on the revised AIH scoring system, simplified criteria, and histological criteria3 |

| HLA data | • Specific HLA for given drugs and general AIH-related HLA |

| Severity** | • As recommended for DILI • nR-based Hy’s law |

| Treatment | • Steroid Therapy (when initiated) • Other immunosuppressant needed • Still on immunosuppressant |

| Outcome | • Remission achieved • Worsening of the disease • Relapse • Liver-related death • Liver transplant |

| Follow-up | • 2–4 weeks, 1–3-6–12-18–24 months after diagnosis and once a year thereafter for 5 years |

| Causality assessment tools | • The RUCAM/CIOMS and its recently improved version RECAM. • The revised and the simplified AIH scoring systems issued by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; anti-LKM1, anti-liver-kidney microsomal type 1 antibody; anti-SLA/LP, anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas antigen; ASMA, anti-smooth muscle/anti-actin antibody; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; INR, international normalised ratio; RUCAM/CIOMS, Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method/Council of International Organization of Medical Sciences; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Between drug exposure and injury onset and improvement.

Imaging studies needed.

Measured at different times of follow-up.

As recommended by Aithal et al.85

DI-ALH management: developing guidelines

The lack of reliable diagnostic biomarkers and an evidence-based treatment paradigm has resulted in limited guidance on how to manage this aspect of DILI.2,25–27 DI-ALH was defined in the EASL Clinical Practice Guideline as “acute DILI with serological and/or histological markers of idiopathic AIH”.2

Conclusions

In summary, DI-ALH as a clinical phenotype is poorly characterised. Establishing new collaborative initiatives will allow for a better understanding of the various DILI signatures. Better characterisation of the different phenotypes of DILI should be the primary focus of future collaborative research, with the ultimate goal of developing novel targeted risk management and therapeutic strategies to optimally manage DILI, AIH and DI-ALH, using precision medicine approaches.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH) is considered a liver injury with laboratory and/or histological features that may be indistinguishable from those of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

Understanding of DI-ALH is limited by the lack of specific markers, while there are no specific pathognomonic findings or individual biomarkers that can be used to establish a diagnosis of idiopathic AIH.

Distinguishing DI-ALH from AIH is crucial since patients with DI-ALH rarely require long-term immunosuppression and the condition often resolves spontaneously after stopping the implicated drug.

The absence of relapse on long-term follow-up without immunosuppressive therapy is an important feature of DI-ALH.

Further evaluation is needed to evaluate the utility of new biomarkers for the diagnosis and definitive characterisation of DI-ALH.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognise the important contributions of all the speakers and participants at this meeting for their valuable insights, questions, and discussion. Participants include the following: Fernando Bessone (Facultad de Ciencias Medicas, Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Hospital Provincial del Centenario, Argentina), Raymundo Paraná (Universidad Federal de Bahía, Brasil), Gideon M. Hirschfield (Toronto Centre for Liver Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), Jack Uetrecht (Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy and Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada), Alessio Gerussi (Division of Gastroenterology, Centre for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy; European Reference Network on Hepatological Diseases (ERN RARE-LIVER), San Gerardo Hospital, Italy), Ana Lleo (Division of Internal Medicine and Hepatology, Department of Gastroenterology, IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Humanitas University, Pieve Emanuele, Milan, Italy), Annarosa Floreani (Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padova, Italy; Scientific Institute for Research, Hospitalization and Healthcare, Verona, Italy), Federica Invernizzi (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Maggiore Policlinico Hospital and Ca’ Granda IRCCS Foundation, Milano, Italy), Federica Pedica (Pathology Unit, Department of Experimental Oncology, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute,Milan, Italy.), Marco Carbone (Division of Gastroenterology, Centre for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca; European Reference Network on Hepatological Diseases (ERN RARE-LIVER), Italy), Massimo Colombo (Liver Centre, San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy), Jose Pinazo, Aida Ortega-Alonso, Judith Sanabria-Cabrera, Camilla Stephens, Ismael Alvarez-Alvarez, Hao Niu, Marina Villanueva, Daniel di Zeo, Antonio Segovia, Gonzalo Matilla, Alejandro Cueto, Enrique del Campo (Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga y Plataforma en Nanomedicina-IBIMA Plataforma BIONAND; UGC de Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd), Málaga, Spain.), Agustin Castiella (Gastroenterology Department, Donostia University Hospital, San Sebastian, Spain), Mar Riveiro-Barciela & Maria Buti (Liver Unit, Internal Medicine Department, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain), Dermot Gleeson (Liver Unit, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK), Jessica Dyson (Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), London, UK), Rosa Miquel (Institute of Liver Studies, Kings College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London, UK), Amber Bozward (Center for Liver and Gastro Research & National Institute of Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, University of Birmingham; Centre for Rare Disease and ERN Rare Liver Centre, Liver Transplant and Hepatobiliary Unit, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, UK.), Nelia Hernandez (Hospital de Clinicas, Montevideo, Uruguay), Averell H. Sherker, Jay H. Hoofnagle, Katrina Loh (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), Ayako Suzuki (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA), John M. Vierling (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA), Mariana Cardoso (Johns Hopkins HospitaL, USA), Yimin Mao (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Disease, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China), Elena Gómez Dominguez (Servicio de Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain).

Ye Htun Oo is funded by The Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust.

Financial support

The present study has been supported by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) cofounded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional-FEDER (contract numbers: PI21/01248; PI19/00883; Clinical research platform of the Carlos III Health Institute: PT20/00127). SCReN and CIBERehd are funded by ISCIII (PI21/01248; PI19/00883; PT20/00127). This publication is based upon work from COST Action “CA17112—Prospective European Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network” supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology, Cost Action CA-17112); www.cost.eu. The following authors are members of CA17112: RJA, ESB, MIL, GPA, GK-U, MR-D, MG-C, EA, AL, SW, AG, HD, MCL, GS, EDM. Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Wiley. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Málaga/CBUA.

Abbreviations

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- ALF

acute liver failure

- ALH

autoimmune-like hepatitis

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ANA

anti-nuclear antibody

- ASMA

anti-smooth muscle antibody

- ChILI

checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury

- DILI

drug-induced liver injury

- DILIN

Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network

- EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- ERN

European Reference Network

- IAIHG

International AIH Group

- RECAM

Revised Electronic Causality Assessment Method

- RUCAM

Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose in relation with this topic. Arie Regev is employee of Eli Lilly, but has no conflict of interest in relation to this topic.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Disclaimer

This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent the US FDA’s views or policies or that of other regulatory agencies.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.033.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

- [1].Andrade RJ, Chalasani N, Björnsson ES, Suzuki A, Kullak-Ublick GA, Watkins PB, et al. Drug-induced liver injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5(1):58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2019;70(6):1222–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lohse AW, Sebode M, Bhathal PS, Clouston AD, Dienes HP, Jain D, et al. Consensus recommendations for histological criteria of autoimmune hepatitis from the international AIH pathology group: results of a workshop on AIH histology hosted by the European reference network on hepatological diseases and the European society of pathology: results of a workshop on AIH histology hosted by the European reference network on hepatological diseases and the European society of pathology. Liver Int 2022;42(5):1058–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Czaja AJ. Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56(4):958–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N, Manns MP, Mayo MJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis in adults and children: 2019 practice guidance and guidelines from the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2020;72(2):671–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 2015;63(4):971–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, Hallal H, Castiella A, Garcia-Bengoechea M, Otazua P, et al. Recurrent drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with different drugs in the Spanish Registry: the dilemma of the relationship to autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 2011;55(4):820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Codoni G, Kirchner T, Engel B, Villamil AM, Efe C, Stattermayer AF, et al. Histological and serological features of acute liver injury after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. JHEP Rep 2023;5(1):100605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sharma R, Verna EC, Simon TG, Soderling J, Hagstrom H, Green PHR, et al. Cancer risk in patients with autoimmune hepatitis: a nationwide population-based cohort study with histopathology. Am J Epidemiol 2022;191(2):298–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Björnsson ES, Stephens C, Atallah E, Robles-Diaz M, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Gerbes A, et al. A new framework for advancing in drug-induced liver injury research. The Prospective European DILI Registry. Liver Int 2023;43(1):115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pape S, Snijders R, Gevers TJG, Chazouilleres O, Dalekos GN, Hirschfield GM, et al. Systematic review of response criteria and endpoints in autoimmune hepatitis by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol 2022;76(4):841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lammert C, Chalasani SN, Atkinson EJ, McCauley BM, Lazaridis KN. Environmental risk factors are associated with autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int 2021;41(10):2396–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hoofnagle JH, Björnsson ES. Drug-induced liver injury - types and phenotypes. N Engl J Med 2019;381(3):264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, et al. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology 2010;51(6):2040–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Andrade RJ, Robles-Diaz M, Castiella A. Characterizing drug-induced liver injury with autoimmune features. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14(12):1844–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Suzuki A, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Miquel R, Smyrk TC, Andrade RJ, et al. The use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 2011;54(3):931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Björnsson ES, Bergmann O, Jonasson JG, Grondal G, Gudbjornsson B, Olafsson S. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: response to corticosteroids and lack of relapse after cessation of steroids. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15(10):1635–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stephens C, Robles-Diaz M, Medina-Caliz I, Garcia-Cortes M, Ortega-Alonso A, Sanabria-Cabrera J, et al. Comprehensive analysis and insights gained from long-term experience of the Spanish DILI Registry. J Hepatol 2021;75(1):86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weiler-Normann C, Schramm C. Drug induced liver injury and its relationship to autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 2011;55(4):747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].deLemos AS, Foureau DM, Jacobs C, Ahrens W, Russo MW, Bonkovsky HL. Drug-induced liver injury with autoimmune features. Semin Liver Dis 2014;34(2):194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Björnsson ES, Medina-Cádiz I, Andrade RJ, Lucena ML. Setting up criteria for drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis through a systematic analysis of published report. Hepatol Commun 2022;6(8):1895–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Immune-mediated drug-induced liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2002;6(3):755–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vuppalanchi R, Gould RJ, Wilson LA, Unalp-Arida A, Cummings OW, Chalasani N, et al. Clinical significance of serum autoantibodies in patients with NAFLD: results from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatol Int 2012;6(1):379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].de Boer YS, Kosinski AS, Urban TJ, Zhao Z, Long N, Chalasani N, et al. Features of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15(1):103–112 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Devarbhavi H, Aithal G, Treeprasertsuk S, Takikawa H, Mao Y, Shasthry SM, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: asia pacific association of study of liver consensus guidelines. Hepatol Int 2021;15(2):258–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chalasani NP, Maddur H, Russo MW, Wong RJ, Reddy KR. Practice parameters committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116(5):878–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fontana RJ, Liou I, Reuben A, Suzuki A, Fiel MI, Lee W, et al. AASLD practice guidance on drug, herbal, and dietary supplement-induced liver injury. Hepatology 2023;77(3):1036–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kirstein MM, Metzler F, Geiger E, Heinrich E, Hallensleben M, Manns MP, et al. Prediction of short- and long-term outcome in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2015;62(5):1524–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lv T, Li M, Zeng N, Zhang J, Li S, Chen S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the incidence and prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis in Asian, European, and American population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34(10):1676–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, Chanay H, Allard C, Guilleminet C, et al. Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology 2002;36(2):451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology 2013;144(7):1419–1425. 25 e1-e1425;quiz e19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Licata A, Maida M, Cabibi D, Butera G, Macaluso FS, Alessi N, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46(12):1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Babany G, Larrey D, Pessayre D, Degott C, Rueff B, Benhamou JP. Chronic active hepatitis caused by benzarone. J Hepatol 1987;5(3):332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rodrigues S, Lopes S, Magro F, Cardoso H, Horta e Vale AM, Marques M, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy: a single center report of 8 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21(24):7584–7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ghabril M, Bonkovsky HL, Kum C, Davern T, Hayashi PH, Kleiner DE, et al. Liver injury from tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists: analysis of thirty-four cases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11(5):558–564 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].van Gerven NM, Verwer BJ, Witte BI, van Erpecum KJ, van Buuren HR, Maijers I, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of autoimmune hepatitis in The Netherlands. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014;49(10):1245–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zimmerman HJ. Drug-induced liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2000;4(1):73–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Atallah E, Oshaughnessy A, Igboin D, Moore Y, Ntata J, Rao A, et al. Prescription event monitoring of checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury and outcomes of rechallenge: a 10-year experience. EMJ Hepatol 2022;10(32). [Google Scholar]

- [39].Berry P, Kotha S, Zen Y, Papa S, El Menabawey T, Webster G, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related cholangiopathy: novel clinicopathological description of a multi-centre cohort. Liver Int 2023;43(1):147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Riveiro-Barciela M, Barreira-Diaz A, Vidal-Gonzalez J, Munoz-Couselo E, Martinez-Valle F, Viladomiu L, et al. Immune-related hepatitis related to checkpoint inhibitors: clinical and prognostic factors. Liver Int 2020;40(8):1906–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li M, Sack JS, Bell P, Rahma OE, Srivastava A, Grover S, et al. Utility of liver biopsy in diagnosis and management of high-grade immune checkpoint inhibitor hepatitis in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 2021;7(11):1711–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zen Y, Yeh MM. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a histology study of seven cases in comparison with autoimmune hepatitis and idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Mod Pathol 2018;31(6):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].De Martin E, Michot JM, Papouin B, Champiat S, Mateus C, Lambotte O, et al. Characterization of liver injury induced by cancer immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Hepatol 2018;68(6):1181–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bril F, Al Diffalha S, Dean M, Fettig DM. Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine: causality or casualty? J Hepatol 2021;75(1):222–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Efe C, Kulkarni AV, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Magro B, Stättermayer A, Cengiz M, et al. Liver injury after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: features of immune-mediated hepatitis, role of corticosteroid therapy and outcome. Hepatology 2022;76(6):1576–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Pares A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2008;48(1):169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Castiella A, Zapata E, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Drug-induced autoimmune liver disease: a diagnostic dilemma of an increasingly reported disease. World J Hepatol 2014;6(4):160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Febres-Aldana CA, Alghamdi S, Krishnamurthy K, Poppiti RJ. Liver fibrosis helps to distinguish autoimmune hepatitis from DILI with autoimmune features: a review of twenty cases. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2019;7(1):21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Björnsson ES, Gunnarsson BI, Grondal G, Jonasson JG, Einarsdottir R, Ludviksson BR, et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury from tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13(3):602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Björnsson HK, Gudbjornsson B, Björnsson ES. Infliximab-induced liver injury: clinical phenotypes, autoimmunity and the role of corticosteroid treatment. J Hepatol 2022;76(1):86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].García-Cortés M, Ortega-Alonso A, Matilla-Cabello G, Medina-Cáliz I, Castiella A, Bonilla-Toyos E, et al. Clinical presentation, causative drugs, and outcome of patients with autoimmune features in the Spanish DILI Regsitry and the Latin American DILI Network. Liver Int 2023. 10.1111/liv.15623. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Björnsson E, Davidsdottir L. The long-term follow-up after idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury with jaundice. J Hepatol 2009;50(3):511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. The clinical usage and definition of autoantibodies in immune-mediated liver disease: a comprehensive overview. J Autoimmun 2018;95:144–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tan EM, Feltkamp TE, Smolen JS, Butcher B, Dawkins R, Fritzler MJ, et al. Range of antinuclear antibodies in “healthy” individuals. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40(9):1601–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zeman MV, Hirschfield GM. Autoantibodies and liver disease: uses and abuses. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24(4):225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sebode M, Schulz L, Lohse AW. “Autoimmune(-Like)” drug and herb induced liver injury: new insights into molecular pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Stephens C, Castiella A, Gomez-Moreno EM, Otazua P, Lopez-Nevot MA, Zapata E, et al. Autoantibody presentation in drug-induced liver injury and idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis: the influence of human leucocyte antigen alleles. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2016;26(9):414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Weber S, Benesic A, Buchholtz ML, Rotter I, Gerbes AL. Antimitochondrial rather than antinuclear antibodies correlate with severe drug-induced liver injury. Dig Dis 2021;39(3):275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;31(5):929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].de Boer YS, van Nieuwkerk CM, Witte BI, Mulder CJ, Bouma G, Bloemena E. Assessment of the histopathological key features in autoimmune hepatitis. Histopathology 2015;66(3):351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, et al. Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology 2014;59(2):661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs–I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46(11):1323–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Garcia-Cortes M, Stephens C, Lucena MI, Fernandez-Castaner A, Andrade RJ. Causality assessment methods in drug induced liver injury: strengths and weaknesses. J Hepatol 2011;55(3):683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hayashi PH, Lucena MI, Fontana RJ, Björnsson ES, Aithal GP, Barnhart H, et al. A revised electronic version of RUCAM for the diagnosis of DILI. Hepatology 2022;76(1):18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lammert C, Zhu C, Lian Y, Raman I, Eckert G, Li QZ, et al. Exploratory study of autoantibody profiling in drug-induced liver injury with an autoimmune phenotype. Hepatol Commun 2020;4(11):1651–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Taubert R, Engel B, Diestelhorst J, Hupa-Breier KL, Behrendt P, Baerlecken NT, et al. Quantification of polyreactive immunoglobulin G facilitates the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2022;75(1):13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Niu H, Ma J, Medina-Caliz I, Robles-Diaz M, Bonilla-Toyos E, Ghabril M, et al. Potential benefit and lack of serious risk from corticosteroids in drug-induced liver injury: an international, multicentre, propensity score-matched analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2023;57(8): 886–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Björnsson ES, Vucic V, Stirnimann G, Robles-Diaz M. Role of corticosteroids in drug-induced liver injury. A systematic review. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:820724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bessone F, Hernandez N, Tagle M, Arrese M, Parana R, Mendez-Sanchez N, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: a management position paper from the Latin American Association for Study of the liver. Ann Hepatol 2021;24:100321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kuzu UB, Oztas E, Turhan N, Saygili F, Suna N, Yildiz H, et al. Clinical and histological features of idiosyncratic liver injury: dilemma in diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res 2016;46(4):277–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Martinez-Casas OY, Diaz-Ramirez GS, Marin-Zuluaga JI, Munoz-Maya O, Santos O, Donado-Gomez JH, et al. Differential characteristics in drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis. JGH Open 2018;2(3):97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Weber S, Benesic A, Rotter I, Gerbes AL. Early ALT response to corticosteroid treatment distinguishes idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury from autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int 2019;39(10):1906–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Liberal R, Macedo G. Acute severe autoimmune hepatitis - timing for steroids and role of other immunosuppressive agents. J Hepatol 2021;75(2):494–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hu PF, Xie WF. Corticosteroid therapy in drug-induced liver injury: pros and cons. J Dig Dis 2019;20(3):122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Andrade RJ, Robles M, Lucena MI. Rechallenge in drug-induced liver injury: the attractive hazard. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2009;8(6):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hunt CM, Papay JI, Stanulovic V, Regev A. Drug rechallenge following drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 2017;66(2):646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sugimoto K, Ito T, Yamamoto N, Shiraki K. Seven cases of autoimmune hepatitis that developed after drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 2011;54(5):1892–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practical Guidelines on the management of acute (fulminant) liver failure. J Hepatol 2017;66(5):1047–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Robles-Diaz M, Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, Stephens C, Medina-Caliz I, Gonzalez-Jimenez A, et al. Use of Hy’s law and a new composite algorithm to predict acute liver failure in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology 2014;147(1):109–118 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kullak-Ublick GA, Andrade RJ, Merz M, End P, Benesic A, Gerbes AL, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: recent advances in diagnosis and risk assessment. Gut 2017;66(6):1154–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Stevens JL, Baker TK. The future of drug safety testing: expanding the view and narrowing the focus. Drug Discov Today 2009;14(3–4):162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Regev A. Drug-induced liver injury and drug development: industry perspective. Semin Liver Dis 2014;34(2):227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Nagral A, Adhyaru K, Rudra OS, Gharat A, Bhandare S. Herbal immune booster-induced liver injury in the COVID-19 pandemic-A case series. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2021;11(6):732–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mieli-Vergani G, Bertoli R, Mazzucchelli L, Nofziger C, Paulmichl M, et al. Atovaquone/proguanil-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis. Hepatol Commun 2017;1(4):293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Aithal GP, Watkins PB, Andrade RJ, Larrey M, Molokhia H, Takikawa H, et al. Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89(6):806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.