Abstract

Purpose

To examine the mediating effect of attitudes towards dementia on the relationship between dementia knowledge and behaviors towards persons with dementia.

Participants and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 313 adults (age ≤ 20 years). Participants were recruited using non-probability convenience sampling from medical clinics, community centers, and supermarkets located in the Wanhua District of Taipei City. Data were collected with the following self-report questionnaires: a demographic survey, validated instruments for dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia (assessed using the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale and the Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire, respectively), and a researcher-developed survey on unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia.

Results

Pearson’s correlation and multiple linear regression analysis indicated that higher scores for dementia knowledge and more positive attitudes about dementia were significantly associated with lower levels of unfriendly behaviors towards persons living with dementia. Mediation analysis using a robust bootstrap test with 5000 samples indicated that attitudes toward dementia had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that increasing public awareness and knowledge about dementia could help the general population develop better attitudes towards dementia, which could subsequently help improve behaviors towards persons living with dementia.

Keywords: attitudes towards dementia, behaviors towards dementia, dementia knowledge, persons with dementia

Introduction

Globally, the number of older adults aged ≥65 years has grown rapidly due to the increasing longevity resulting from improved medical care. Population aging has become a common phenomenon especially in developed countries and cognitive ability declines with age, leading to an increased risk of dementia among older adults. According to Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) and the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2020 there were approximately 55 million persons living with dementia worldwide, with the number growing at a rate of 10 million new cases every year, implying an average of one new case every 3 seconds.1,2 Taiwan has entered the stage of an aged society. In 2022, there were nearly 320,000 persons living with dementia in Taiwan, accounting for 7.64% of the population above 65 years of age; the number is expected to rise to 800,000 by 2051, which will be approximately 10.67% of the over-65 population.3

Dementia is a cognitive impairment with progressive deterioration of brain function that involves a range of symptoms such as memory loss, difficulties with concentrating, planning, and communicating, as well as problems with visual perception and orientation. Persons living with dementia are often faced with mental and physical impairments that cause decreases in functional abilities and increases in physical and psychological challenges, which can result in conduct from others that discriminates and violates their human rights.

A global survey conducted by ADI in 2019 found that between 35% and 57% of persons living with dementia had experienced unfair treatment by another in social or intimate relationships, which included being avoided, ignored, neglected, and excluded because of the stigma associated with dementia.4 The stigma of dementia has been shown to be associated with depression, anxiety and low self-esteem, which can also delay help-seeking and in turn affects the quality of life and disease adaptation of persons living with dementia.5,6 The stigma of dementia affects not only persons with dementia but also how caregivers respond to a family member with dementia. A study conducted in Japan by Aihara et al in 2020 found that half of older adults would feel ashamed of a family member with dementia.7 This stigma of dementia is global, with over 35% of caregivers worldwide reporting that they have hidden a family member’s diagnosis of dementia from others.4

In 2017, the WHO called for national public health agendas to highlight dementia as a priority and to better respond to the needs of the rapidly rising population with dementia.8 The need for building dementia-friendly communities is increasingly important as the concern and awareness of dementia grows in many countries around the world. Dementia-friendly communities provide support that allows persons living with dementia to actively engaged and regarded as valued citizens.9 Attitudes and behaviors of the public towards persons with dementia that encourage inclusivity are the key factors in building a dementia-friendly community. Although two previous studies showed that dementia knowledge was significantly associated with attitudes towards persons with dementia,10,11 two studies found an insignificant association between dementia knowledge and attitudes towards persons with dementia,12,13 making the association inconclusive. A recent study in South Korea on the relationship between dementia knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors found knowledge of dementia reduced negative behaviors indirectly, whereas a negative attitude towards dementia indirectly increased negative behaviors,14 indicating a significant effect of attitude on dementia knowledge and behavioral intention.

Previous studies showed that healthcare professionals’ knowledge and attitudes are important in providing optimum dementia care.11,15,16 However, there is limited research about dementia knowledge, attitudes and behaviors in the context of the general population in the community. Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare initiated an active response to the global action plan of the WHO in 2018 by formulating guidelines for building dementia-friendly communities.17 However, there are limited data on the relationship between dementia knowledge, attitudes and behaviors towards persons with dementia in the Taiwanese community. Understanding how knowledge and attitudes affect behaviors towards persons with dementia can provide information that will enable communities to become dementia-friendly. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the relationships and examine the potential mediating effect of attitudes towards dementia on the relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. Results from this research may help to better target public health messaging campaigns designed to reduce the stigma for persons living with dementia. The following hypotheses were tested: (1) dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia would be significantly negatively correlated with unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia and (2) controlling for covariates, attitudes towards dementia would have a mediating effect on the relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a cross-sectional study reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations.18 Residents were recruited from the Wanhua District of Taipei City from hospital family medicine clinics, community service centers, and supermarkets using a non-probability convenience sampling method. Wanhua District is not only the oldest developed area in Taipei City but is also the district with the largest number of older adults and low-income households. The number of residents living with dementia in this district is estimated to be one of the highest in Taipei City. The continued growth of this population indicates the urgent need to build a community that is dementia-friendly.

Participants and Procedure

Residents of Taiwan were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) currently living in Wanhua District, Taipei City; (2) age ≥20 years; and (3) able to communicate in Chinese or Taiwanese. Residents were excluded if they had severe hearing impairment, had difficulty communicating with the researcher, or could not understand the content of the questions. The researchers explained the purpose of the research and the time required for the survey to each resident. Residents willing to participate provided written informed consent before data were collected.

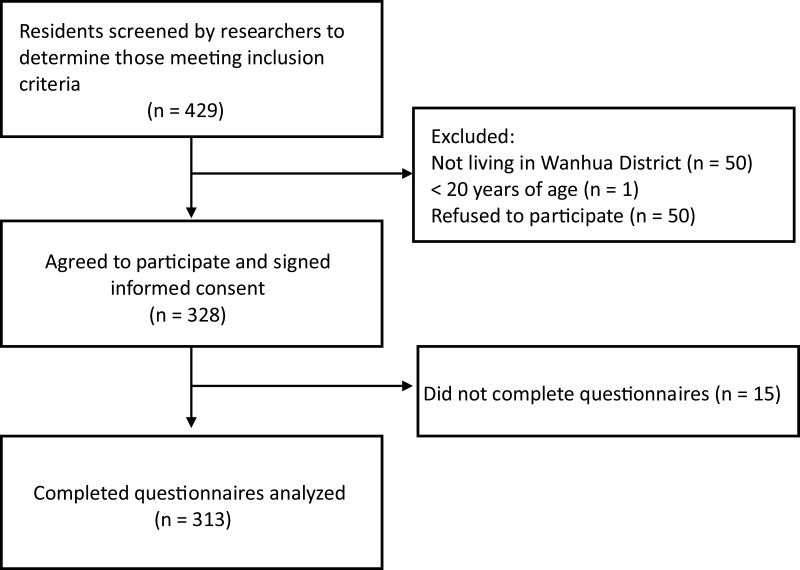

The sample size was estimated using G-power version 3.1, assuming a power of 0.90, and the α level set at 0.05. The effect size was set at a minimum value of 0.14 in reference to the correlation coefficient of 0.14 between attitude scores and care approach scores in community health professionals.11 The research framework of this study included ten independent variables. Therefore, the minimum sample size was estimated to be 157. During the study period, 429 potentially eligible participants were contacted and invited to be screened to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria for the study; of those, 328 fit the inclusion criteria, provided informed consent, and agreed to fill out the questionnaires. Among the 328 participants, 15 did not complete the questionnaires due to lack of time or interest. Consequently, 313 participants who met the inclusion criteria provided completed questionnaires for this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant screening and recruitment.

Measures

A self-administered survey questionnaire collected information on participants’ demographic characteristics, which included gender, age, educational level, employment status, living arrangement, health status and experience with caregiving for persons with dementia.10,11 Validated instruments collected participants’ self-perceived levels of dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia; two researcher-developed questions were used to evaluate unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. Details are provided below.

Assessment of Dementia Knowledge

Knowledge of dementia was assessed using a Taiwanese version of the 30-item Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS) developed by Carpenter et al.19 The ADKS is a self-rated questionnaire originally developed for assessing knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease and has been shown to be a reliable instrument for assessing knowledge of dementia.10,20–22 The scale items assess seven key areas of knowledge about the disease: risk factors, assessments and diagnoses, the course of the disease, symptoms, life impact, caregiving, treatment, and management. Each item is answered true or false (1 or 0). In the present study, total scores were obtained by summing the number of correct responses, scores ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating a greater level of knowledge about dementia. The Taiwanese version of the scale for adults of various ages had a Cronbach’s α of 0.78.10 In this study, the Cronbach’s α for reliability of the ADKS was 0.87.

Assessment of Attitudes Towards Dementia

Participants’ attitudes towards dementia were assessed with the Chinese version of the 19-item self-report Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire (ADQ).15 The ADQ is comprised of the domains of hopefulness and person-centeredness.23,24 Each item is a statement, which is rated on 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Eight items ask the participant about their attitude towards hopefulness, which addresses the degree of hope for persons living with dementia; the 11 items on person-centeredness assess the degree the participant endorses person-centered care as opposed to considering that all persons living with dementia have the same strengths and limitations. The total score ranges between 19 and 95, with higher total scores indicating a more positive attitude towards persons with dementia. The ADQ has been shown to have good reliability (Cronbach’s α of 0.76 for hopefulness and 0.85 for person-centeredness) for residential caregivers in Hong Kong.15 In this study, the Cronbach’s a for hopefulness was 0.67, and person-centeredness was 0.68.

Assessment of Unfriendly Behaviors Towards Persons with Dementia

The unfriendly behavior survey was developed by the research team of this study. A focus group comprised people living with dementia and caregivers developed six statements about attitudes of adults in the community towards persons living with dementia. These six statements were used to assess participant’s unfriendly behaviors: (1) “Once a person has dementia, he doesn’t know anything”; (2) “If a family member is diagnosed with dementia, it is better to keep it a secret from friends and other family members”; (3) “Persons living with dementia should stay at home and avoid social interactions”; (4) “Persons living with dementia are dangerous most of the time and they may harm others or themselves”; (5) “If I were given a choice, I would prefer not to interact or participate in activities together with a person living with dementia”; and (6) “Institutional care is the best arrangement for people living with dementia”. Respondents were instructed to rate each statement on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = uncertain; 4 = agree; and 5 = strongly agree. Total scores ranged from 6 to 30; higher total scores indicated a greater likelihood of unfriendly behavior towards persons with dementia. The content validity of the questionnaire was verified by five experts in the field of long-term care. The content validity index was 0.98, and the Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency reliability was 0.70.

Data Collection

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee National Taiwan University prior to data collection (IRB case number: 202005EM056). Data were collected from September 2020 to December 2020 by three research assistants trained in interviewing participants. A researcher explained the study objective, research process, and assurance that anonymity of their data would be maintained to the residents in detail after initiating contact. After obtaining informed consent, participants could choose to fill out the survey by themselves or via a face-to-face interview with one of the research assistants. Each survey interview took between 15 and 20 minutes to complete. The surveys were coded to maintain anonymity and protect patient privacy.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Descriptive statistics were used to report the socio-demographic characteristic of the respondents, which included frequency (percentage), mean, and standard deviation. Independent sample t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to examine the differences in behaviors towards persons with dementia among participants with different demographic characteristics. We also performed Pearson’s correlation analysis to measure the strength of the linear relationship between dementia knowledge, attitudes and behaviors towards persons with dementia. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify predictors of behaviors towards persons living with dementia and investigate the association between dementia knowledge and behaviors towards persons living with dementia. The SPSS PROCESS procedure was applied to test the mediation model with the model-4 setup.25 In examining the mediating effect of attitudes towards dementia, the indirect effect of dementia knowledge on behaviors towards people living with dementia was also tested using a bootstrapping test with 5000 bootstrap samples, to confirm the mediation effect of attitudes towards persons living with dementia.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Demographic characteristics of the 313 respondents are shown in Table 1. A total of 108 participants (34.5%) were male and 205 (65.5%) were female. The mean age of all participants was 53.24 years (SD = 17.20); most (66.1%) were ≤64 years of age. Most participants had an educational level of college or greater (60.7%); more than half were unemployed (56.2%) and 41.0% were living with an adult ≥65 years old. Most participants perceived their health status as normal (58.8%) and had no dementia caregiving experience (61.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants (N = 313)

| Variable | n | % | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 313 | 53.24 | 17.20 | 20–90 | |

| 20–40 | 87 | 27.8 | |||

| 41–64 | 120 | 38.3 | |||

| ≥ 65 | 106 | 33.9 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 108 | 34.5 | |||

| Female | 205 | 65.5 | |||

| Education | |||||

| ≤ Senior high school | 123 | 39.3 | |||

| College or above | 190 | 60.7 | |||

| Chronic diseases | 0.78 | 0.97 | 0–6 | ||

| No | 162 | 51.8 | |||

| Yes | 151 | 48.2 | |||

| Perceived health status | 3.22 | 0.76 | 1–5 | ||

| Poor or very poor | 37 | 11.8 | |||

| Normal | 184 | 58.8 | |||

| Good or very good | 92 | 29.4 | |||

| Employment status | |||||

| Unemployed | 176 | 56.2 | |||

| Employed | 137 | 43.8 | |||

| Living with an adult ≥ 65 years old | |||||

| No | 184 | 59.0 | |||

| Yes | 128 | 41.0 | |||

| Experience with dementia caregiving | |||||

| No | 192 | 61.5 | |||

| Yes | 120 | 38.5 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Unfriendly Behaviors Related to Dementia

Participants’ responses to the self-report questionnaires and unfriendly behaviors survey are shown in Table 2. The mean score for dementia knowledge was 15.15 (SD = 5.40), showing an average of 50% correct responses to the 30 questions on the ADKS. The mean score for attitudes towards dementia was 66.65 (SD = 7.13), indicating a somewhat positive attitude towards persons living with dementia. The mean total score on the Unfriendly Behaviors Survey was 13.12 (SD = 1.28).

Table 2.

Responses to Questionnaires About Dementia and the Unfriendly Behaviors Survey (N = 313)

| Variable | n | % | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia knowledge | 15.15 | 5.40 | 0–27 | ||

| Attitudes towards dementia | 66.66 | 7.13 | 44–89 | ||

| Unfriendly Behaviors Survey, Total score | 13.59 | 3.20 | 6–24 | ||

| Items for Unfriendly Behaviors Survey, grouped score rating | |||||

| Persons with dementia do not know anything | |||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 207 | 66.1 | |||

| Uncertain | 73 | 23.3 | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 33 | 10.5 | |||

| A family member’s diagnosis of dementia should be hidden | |||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 284 | 90.7 | |||

| Uncertain | 19 | 6.1 | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 10 | 3.2 | |||

| Persons living with dementia should stay at home | |||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 262 | 83.7 | |||

| Uncertain | 33 | 10.5 | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 18 | 5.8 | |||

| Prefer not to interact with persons living with dementia | |||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 220 | 70.3 | |||

| Uncertain | 51 | 16.3 | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 42 | 13.4 | |||

| Persons living with dementia are dangerous most of the time | |||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 167 | 53.4 | |||

| Uncertain | 84 | 26.8 | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 62 | 19.8 | |||

| Institutional care is the best arrangement | |||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 162 | 51.8 | |||

| Uncertain | 102 | 32.6 | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 49 | 15.7 |

Notes: Unfriendly Behaviors Survey = unfriendly behaviors towards persons living with dementia; Dementia knowledge = score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale; Attitudes towards dementia = score on the Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

When item scores for unfriendly behaviors were grouped into three categories (disagree or strongly disagree, uncertain, and agree or strongly agree; Table 2), most participants reported they disagreed with the idea of hiding a family member’s diagnosis of dementia (90.7%), that persons living with dementia should stay at home (83.7%), and that they prefer not to interact with persons living with dementia (70.3%). Nearly one in five participants reported they thought persons living with dementia are dangerous (19.8%) and 15.7% thought persons living with dementia should be institutionalized.

Factors Correlated with Scores for Unfriendly Behaviors Towards Persons with Dementia

We examined if there were associations between demographic characteristics as well as scores for dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia for participants and scores for unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Characteristics, Knowledge, and Attitudes About Dementia and Unfriendly Behaviors Towards Persons Living with Dementia

| Variable | Total UBS score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | F/t | p | r | p | |

| Characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 20.89 | < 0.001 | 0.34 | <0.001 | |

| (1) 20–40 | 12.54 (2.84) | ||||

| (2) 41–64 | 13.01 (2.98) | ||||

| (3) ≥ 65 | 15.10 (3.19) | ||||

| Post hoc test | (1) < (3) | ||||

| Gender | −0.43 | 0.670 | |||

| Male | 13.48 (3.01) | ||||

| Female | 13.64 (3.30) | ||||

| Education | 4.70 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤ Senior high school | 14.61 (3.29) | ||||

| ≥ College | 12.93 (2.96) | ||||

| Chronic diseases | 1.83 | 0.068 | 0.11 | 0.047 | |

| No | 13.90 (3.34) | ||||

| Yes | 13.24 (3.03) | ||||

| Perceived health status | 0.22 | 0.805 | 0.04 | 0.523 | |

| Poor or very poor | 13.38 (3.58) | ||||

| Normal | 13.68 (3.11) | ||||

| Good or very good | 13.48 (3.25) | ||||

| Employment status | 3.84 | < 0.001 | |||

| Unemployed | 14.18 (3.35) | ||||

| Employed | 12.83 (2.83) | ||||

| Living with an adult ≥ 65 years old | 2.26 | 0.024 | |||

| No | 13.91 (3.06) | ||||

| Yes | 13.09 (3.33) | ||||

| Experience with dementia caregiving | 0.82 | 0.417 | |||

| No | 13.70 (3.31) | ||||

| Yes | 13.40 (3.04) | ||||

| Dementia knowledge | −0.25 | <0.001 | |||

| Attitudes towards dementia | −0.54 | <0.001 | |||

Notes: Total UBS score = total score on the Unfriendly Behavior Survey; Dementia knowledge = score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale; Attitudes towards dementia = score on the Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire.

Analysis indicated age, education and employment status were significantly associated with scores for unfriendly behaviors. Participants ≥65 years of age had higher USB total scores than participants 20–40 and 41–64 years of age; post hoc analysis indicated that total scores for those ≥65 years of age were significantly higher compared with participants aged 20–40 years (F = 20.89, p < 0.001). In terms of educational level, respondents who completed high school or below had higher scores for unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia (t = 4.70, p <0.001) compared with those holding a college degree or above.

Pearson’s correlation demonstrated that scores for dementia knowledge were negatively correlated with scores for unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia (r = −0.25, p < 0.001). A negative correlation was also observed between scores for attitudes and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia (r = −0.54, p < 0.001).

Factors Correlated with Scores for Dementia Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Persons with Dementia

We examined the relationship between scores for dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia and found a positive and significant correlation (r = 0.16, p = 0.006), suggesting that community dwelling adults with greater knowledge about dementia were likely to have a positive attitude towards persons living with dementia. When we examined if there were characteristics associated with scores for dementia knowledge and attitudes, we found that participants with less than a high-school education had significantly lower scores for knowledge (t = −3.55, p < 0.001) and attitude (t = −4.07, p < 0.001) than those with a college education or above. Participants with experience caring for persons with dementia had higher knowledge scores (t = −2.25, p = 0.025), but not significantly higher scores for attitude (t = 0.61, p = 0.542) compared with participants with no dementia caregiving experience.

Factors Associated with Unfriendly Behaviors Towards Persons with Dementia

Analysis with multiple linear regressions also showed a significant negative association between scores for unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia and dementia knowledge (β = −0.08, p = 0.003), after adjusting for the potential confounding factors of gender, age, educational level, employment status, and living arrangement (Table 4). Participants with higher scores for dementia knowledge were more likely to have lower scores for unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. Other significant predictors of scores for unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia included age ≥65 years old (β = 1.16, p = 0.004), living with an older adult (β = −1.17, p < 0.001) and attitudes towards dementia (β = −0.20, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression Demonstrating Relationships Between Scores for Behaviors Towards Persons with Dementia, Demographics, Dementia Knowledge, and Attitudes Towards Dementia

| Variable | Scores for Unfriendly Behaviors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | |

| Age (vs 41–64 years old) | |||

| 20–40 years old | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.56 |

| ≥ 65 years old | 1.16 | 0.40 | 0.004 |

| Education (vs ≤ Senior High school) | |||

| College | −0.53 | 0.33 | 0.111 |

| Employment status (vs Unemployed) | |||

| Employed | −0.31 | 0.35 | 0.385 |

| Living with older adults (vs No) | |||

| Yes | −1.17 | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Dementia knowledge | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.003 |

| Attitudes towards dementia | −0.20 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

Mediating Effect of Attitudes Towards Dementia

The mediating effect of attitudes towards dementia was examined using a bootstrap test (Table 5). Model 1 indicated that the association between dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia was significant (β = 0.15, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.01–0.30). Model 2 showed that attitudes towards dementia were a significant predictor of unfriendly behaviors towards people living with dementia (β = −0.21, 95% CI: −0.26, −0.17).

Table 5.

Mediation Analysis of Attitudes Towards Dementia and Unfriendly Behaviors Towards Persons Living with Dementia

| Variable | Attitudes Towards Dementia | Unfriendly Behaviors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |||

| Dementia knowledge | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.039 | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | ||

| Attitudes towards dementia | −0.21 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Education (vs ≤ Senior High school) | 3.99 | 0.83 | < 0.001 | −0.86 | 0.32 | 0.007 | ||

| Living with older adults (vs Not) | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.334 | −0.90 | 0.30 | 0.003 | ||

| R2 = 0.25 | R2 = 0.35 | |||||||

| F = 7.12 | p < 0.001 | F = 41.13 | p <0.001 | |||||

| Effect | SE | p | 95% CI, lower, upper | % | ||||

| Total effect | −0.13 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | −0.191, −0.065 | 100.0 | |||

| Direct effect | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | −0.149, −0.040 | 74.2 | |||

| Indirect effect a | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.060, −0.040 | 25.8 | ||||

Note: aTested with 5000 bootstrapping samples.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Dementia knowledge was also a significant predictor of behavior towards people living with dementia (β = −0.09, 95% CI: −0.15, −0.04) after controlling for the mediator (attitudes towards dementia). The predictors accounted for approximately 35% of the variance in behavior towards people with dementia (R2 = 0.35). The indirect effect of dementia knowledge on behavior towards people with dementia was tested using 5000 bootstrapping samples. The results indicated that the indirect effect of dementia knowledge on behavior towards people with dementia was significant (β = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.06, −0.04), indicating that attitudes towards dementia had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between dementia knowledge and behavior towards people living with dementia.

Discussion

We examined the mediating effect of attitudes towards dementia on the relationship between dementia knowledge and behaviors towards persons with dementia. Analysis of the data demonstrated that dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia were significantly negatively correlated with unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia; attitudes towards dementia had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors. These findings support both hypotheses, which suggest there is a need to provide additional education to facilitate dementia-friendly communities.

Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare began encouraging dementia-friendly communities in 2018 with the Dementia Prevention and Care Policy and Action Plan 2.0.26 However, despite several years of promoting dementia-friendly behaviors, people in Taiwanese communities continue to have varying degrees of prejudice and unfriendly behaviors towards persons living with dementia, which is in line with the ADI global survey of 2019.4 Nearly one in five of respondents in our study believed that people living with dementia are dangerous and should be institutionalized. One in ten thought that once a person has developed dementia, they do not know anything. These dementia stigmas may result in delayed access to diagnosis and care and put a person living with dementia at a disadvantage.

Our findings showed that less than one-tenth of the participants was either uncertain or inclined to hide the diagnosis of dementia from a family member. This result is in line with the ADI global survey of 2019, which reported that about 91% of survey respondents thought a diagnosis of dementia should not be concealed.4 However, our findings are in contrast to surveys from residents of Kobe, Japan and Shanghai, China that showed half of respondents would feel ashamed of a family member with dementia and would be inclined to hide the diagnosis from others.7,27 Despite the low proportion of our participants who reported that they were likely to conceal a family member’s diagnosis of dementia, it is distant from the goal of the ADI, which is zero concealment.4

Nearly one-third of participants in this study were uncertain or agreed that they would choose not to interact with persons living with dementia. This result is slightly less than the ADI global survey, which reported about 43% of respondents avoided or shunned persons living with dementia.4 The low level of willingness to interact with people with dementia by community residents may be due to the false perception that people with dementia are violent or dangerous and avoidance of people with dementia may also be due to an inability to interact with people with dementia. Therefore, removing stigma associated with dementia and providing community members with skills to increase positive interactions with people living with dementia should be incorporated into plans for a dementia-friendly community.

The mean scores for knowledge and attitudes towards dementia in this study were lower than the mean scores obtained in most previous studies that used the ADKS to measure dementia knowledge11,19,20,28–30 and ADQ to measure attitudes towards dementia.31–33 One explanation for the lower scores in this study may be the older age of the respondents, which may make it more likely that these participants have retained negative feelings towards dementia because of the stigma associated with the disease.4 However, our findings are similar to previous studies, which have shown older adults are more likely to have lower scores for knowledge and a more negative attitude about dementia compared with younger adults.32,34,35

One other explanation for the lower scores for knowledge and attitudes in our study compared with others is that many previous studies included a partial or total sample of health professionals.11,16,19,20,29,30 All participants in our study were from the general population in the community, whose scores for knowledge are more likely to be lower. Compared with health professionals, a lay person, especially one who has never taken care of a person with dementia, has more difficulty empathizing with a person with dementia, or having a “hopefulness” and “person-centeredness” attitude, which is due to a lack of knowledge and skills one would obtain from providing support for a person with dementia.15,16,33

Finally, the lower scores for knowledge and attitude towards dementia might be due to cultural or socioeconomic factors.4,5,34 The Wanhua District has a relatively low socioeconomic status compared to other districts in Taipei city.

The influence of age on unfriendly behaviors was demonstrated in our regression model. Participants 20–40 years of age had significantly lower scores for unfriendly behaviors than those ≥65 years. Life experiences might explain this finding. Individuals 20–40 years of age are less likely to have experience interacting with persons living with dementia compared with those ≥65, who are often partners of individuals with dementia.

In contrast with previous studies indicating personal experience with dementia is significantly associated with attitudes and behaviors towards dementia,32,35 our analysis showed no association between experience and higher scores on the ADQ or UBS, which suggests that personal experience may not necessarily lead to positive attitudes and behaviors. Our findings are similar to those of Chang and Hsu (2020) who demonstrated that participants who had cared for persons with dementia were more likely to experience negative attitudes due to feelings of being ashamed,10 which often stems from the stigma associated with dementia36,37 and can increase caregiver burden.38 In addition, frailty can accelerate the course of dementia, which may further increase the burden on caregivers and affect their caregiving experience.39 Therefore, additional interventions4,35,36 should be provided to increase dementia knowledge and reduce stigma towards dementia.37,38 Finally, assessments of frailty for persons with dementia should also be provided.

Relationship Between Dementia Knowledge, Attitudes and Unfriendly Behaviors Towards Persons with Dementia

Our data indicated that higher dementia knowledge and positive attitude were significantly associated with lower levels of unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. Participants with higher scores for knowledge and a more positive attitude about dementia were less likely to want to hide the diagnosis of dementia of a family member from others and were more willing to have social interactions with persons living with dementia. The finding is partially consistent with a recent study, which found that participants with less knowledge of dementia were more likely to feel ashamed of persons with dementia.10 However, the same study showed no significant relationship between knowledge of dementia and avoidance of persons with dementia. A study by Lim in 2020 revealed an insignificant direct effect of dementia knowledge on behavioral intention.14

The present study found a significant association between dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia. Our result is in line with a previous study that also showed professional staff with poor dementia knowledge tended not to use a person-centered care approach,11,16 suggesting a negative attitude about dementia. However, an online and paper survey in the UK found that having had contact with persons with dementia was associated with a positive attitude about dementia, and the level of dementia knowledge was not significant.40 However, one study indicated knowledge about dementia was not positively correlated with attitudes. When a sample of citizens of Cambodia, the Philippines, and Fiji were surveyed, attitudes towards persons with dementia were positive despite low levels of dementia knowledge, and predictors of positive attitudes were country specific.41 Therefore, knowledge and attitude might be independent domains in certain social and cultural environments.10

Mediating Effect of Attitudes Towards Dementia

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine the mediating effect of attitudes towards dementia on the relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors towards persons living with dementia in Taiwan. The mediation effect of attitudes towards dementia was significant in this study using the bootstrap test for mediation analysis.

Our results are consistent with a recent study in South Korea, which showed that dementia knowledge reduced a negative behavioral intention through a positive cognitive attitude.14 However, dementia knowledge was also shown to increase the negative behavioral intention through a negative affection and behavioral attitude towards dementia after controlling the variables in some studies.10,14,35 This indicates that an intervention that simply provides knowledge about dementia will not necessarily be beneficial for reducing unfriendly behaviors, and there may even be a negative relationship between awareness and unfriendliness. Therefore, interventions that increase contact with persons with dementia to allow them to be viewed with a positive, hopeful attitude could encourage a willingness to interact, thus increasing person-centeredness, which could help develop dementia friendly behaviors.

Therefore, interventions should not only be focused on disease-related knowledge but also on assisting in understanding how to interact with persons with dementia. Understanding can help to resolve fear and provide experiences of successfully coexisting with persons with dementia through various virtual simulation methods or with actual in-person contact,30,42 which can help improve positive attitudes and increase the willingness to interact with persons with dementia. Future studies that survey caregivers who have had positive experiences with dementia care could also improve perceptions of persons with dementia. In addition, providing adequate post-diagnosis support and friendly service can help reduce the desire to conceal a family member’s diagnosis of dementia.

Limitations and Future Research

First, the present study was a cross-sectional survey design, which prevents determining the causal relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. Second, the study participants were collected from the Wanhua District through convenience sampling, and thus the findings may not be generalizable to other regions of Taiwan. Third, the ADKS was used to assess dementia knowledge of the participants. Dementia is a general term used to describe a number of symptoms affecting the brain. Alzheimer’s disease is a common type of dementia but not the only one. Other types of dementia include vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia. The ADKS was developed to assess the knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease and thus may not reflect the real level of dementia knowledge of the respondents in this study. In addition, although the ADQ is a validated instrument, it may not be suitable for assessing attitudes of the population in Taiwan towards dementia. A localized assessment tool is needed in future studies to measure the attitudes towards dementia of Taiwanese people, who have cultural differences from other Asian countries. Fourth, our findings are limited by the quantitative nature of the study in assessing the participants’ attitudes and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. A qualitative study should be conducted in the future to explore perceptions, attitudes and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia, which would strengthen the findings of this study. Fifth, we did not collect data about participants’ socio-economic status, which could also influence attitudes towards dementia. Thus, we recommend this information be part of the survey data in future studies. Finally, the results obtained need to be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. Thus, future studies with a larger sample size are warranted to support these findings.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of differential treatment or discrimination still exists in many communities, including Taiwan, thus advocating dementia-friendly communities should be emphasized. Dementia knowledge was significantly associated with attitudes and behaviors towards persons with dementia. Attitude towards dementia was a significant mediator in the relationship between dementia knowledge and unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. It is recommended that the general publics’ level of dementia knowledge be increased to improve attitudes and reduce unfriendly behaviors towards persons with dementia. Changes in these variables could help create a more dementia-friendly community and diminish the stigma of dementia, allowing persons with dementia to be accepted, respected and supported in their life. However, more research is needed to establish effective strategies to increase knowledge and attitude towards dementia and increase contact among the general population and persons with dementia.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who took part in the study.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 109-2813-C-227-005-B) and Ministry of Education (109EH02-2).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia statistics. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2022. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/dementia-statistics/. Accessed May 21, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Dementia. World Health Organization; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Accessed December 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taiwan Alzheimer Disease Association. Estimation of dementia population in Taiwan. Taiwan Alzheimer Disease Association; 2022. Available from: http://www.tada2002.org.tw/About/IsntDementia. Accessed May 30, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer report 2019: attitudes to dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2019. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low L-F, Purwaningrum F. Negative stereotypes, fear and social distance: a systematic review of depictions of dementia in popular culture in the context of stigma. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):477. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01754-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillipson L, Magee C, Jones S, Reis S, Skladzien E. Dementia attitudes and help-seeking intentions: an investigation of responses to two scenarios of an experience of the early signs of dementia. Aging Mental Health. 2015;19(11):968–977. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.995588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aihara Y, Kato H, Sugiyama T, Ishi K, Goto Y. Public attitudes towards people living with dementia: a cross-sectional study in urban Japan (innovative practice). Dementia. 2020;19(2):438–446. doi: 10.1177/1471301216682118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487-eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed June 20, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darlington N, Arthur A, Woodward M, et al. A survey of the experience of living with dementia in a dementia-friendly community. Dementia. 2021;20(5):1711–1722. doi: 10.1177/1471301220965552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang CY, Hsu HC. Relationship between knowledge and types of attitudes towards people living with dementia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11). doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Xiao LD, Luo Y, Xiao SY, Whitehead C, Davies O. Community health professionals’ dementia knowledge, attitudes and care approach: a cross-sectional survey in Changsha, China. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0821-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khonje V, Milligan C, Yako Y, Mabelane M, Borochowitz KE, de Jager CA. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about dementia in an urban Xhosa-Speaking Community in South Africa. Adv Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015;4:21–36. doi: 10.4236/aad.2015.42004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulyani S, Artanti ER, Saifullah AD. Knowledge and attitudes towards people with dementia among general population in Yogyakarta. Proceed Third Inter Conf Sustain Innovat. 2019;15:230–235. doi: 10.2991/icosihsn-19.2019.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim YO. The relationship among dementia knowledge, attitude and behavioral intention of residents. Crisisonomy. 2020;16(4):17–32. doi: 10.14251/crisisonomy.2020.16.4.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung JLM, Sezto NW, Chan WC, Cheng SP, Tang SH, Lam LCW. Attitudes and perceived competence of residential care homes staff about dementia care. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;8(1):21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao W, Moyle W, Wu M-LW, Petsky H. Hospital healthcare professionals’ knowledge of dementia and attitudes towards dementia care: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31(13–14):1786–1799. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dementia prevention and care policy and action plan 2.0 2018–2025. Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2019. Available from: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-139-541-2.html. Accessed April 18, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carpenter BD, Balsis S, Otilingam PG, Hanson PK, Gatz M. The Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale: development and psychometric properties. Gerontologist. 2009;49(2):236–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amano T, Yamanaka K, Carpenter BD. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale. Dementia. 2019;18(2):599–612. doi: 10.1177/1471301216685943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EJ, Jung JY. Psychometric properties of the Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale--Korean version. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2015;45(1):107–117. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2015.45.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yilmaz F, Çolak M. The validity and reliability of a Turkish Version of the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS). Turkiye Klin J Health Sci. 2020;5:594–602. doi: 10.5336/healthsci.2020-74195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerritsen DL, van Beek APA, Woods RT. Relationship of care staff attitudes with social well-being and challenging behavior of nursing home residents with dementia: a cross sectional study. Aging Mental Health. 2019;23(11):1517–1523. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1506737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lintern T, Woods B, Phair L. Before and after training: a case study of intervention. J Dementia Care. 2000;8:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dementia friendly Taiwan by 2025. Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2022. Available from: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/dl-65822-72e148a6-d18e-4248-a4e7-43472e02353d.html. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Fang W, Su N, Liu Y, Xiao S, Xiao Z. Survey in Shanghai communities: the public awareness of and attitude towards dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11(2):83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2010.00349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorge C, Cetó M, Arias A, et al. Level of understanding of Alzheimer disease among caregivers and the general population. Neurología. 2021;36(6):426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kada S. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease among Norwegian undergraduate health and social care students: a survey study. Educ Gerontol. 2015;41(6):428–439. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2014.982009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimzey M, Mastel-Smith B, Alfred D. The impact of educational experiences on nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes toward people with Alzheimer’s disease: a mixed method study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;46:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter G, Brown Wilson C, Mitchell G. The effectiveness of a digital game to improve public perception of dementia: a pretest-posttest evaluation. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0257337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheston R, Hancock J, White P. A cross-sectional investigation of public attitudes toward dementia in Bristol and South Gloucestershire using the approaches to dementia questionnaire. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(10):1717–1724. doi: 10.1017/s1041610216000843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Vries K, Drury-Ruddlesden J, McGill G. Investigation into attitudes towards older people with dementia in acute hospital using the Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire. Dementia. 2020;19(8):2761–2779. doi: 10.1177/1471301219857577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Anstey KJ, Mortby ME. Who displays dementia-related stigma and what does the general public know about dementia? Findings from a nationally representative survey. Aging Mental Health. 2022;1–9. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2022.2040428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosato M, Leavey G, Cooper J, De Cock P, Devine P. Factors associated with public knowledge of and attitudes to dementia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0210543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang -C-C, J-A S, Lin C-Y. Using the affiliate stigma scale with caregivers of people with dementia: psychometric evaluation. Alzheimer’s ResTher. 2016;8(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0213-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu YL, Chang CC, Lee CH, et al. Associations between affiliate stigma and quality of life among caregivers of individuals with dementia: mediated roles of caregiving burden and psychological distress. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2023;6(2):64–71. doi: 10.4103/shb.shb_67_23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Werner P, Mittelman MS, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Family stigma and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontologist. 2011;52(1):89–97. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koch G, Belli L, Giudice TL, et al. Frailty among Alzheimer’s disease patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12(4):507–511. doi: 10.2174/1871527311312040010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung AYM, Leung SF, Ho GW, et al. Dementia literacy in Western Pacific countries: a mixed methods study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(12):1815–1825. doi: 10.1002/gps.5197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton C, Hadjistavropoulos T, Gallant NL, MacNab YC. Age differences in attitudes about older adults with dementia. Ageing Soc. 2021;41(1):121–136. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X19000965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Richardson A, Werner P, Anstey KJ. Dementia stigma reduction (DESeRvE) through education and virtual contact in the general public: a multi-arm factorial randomised controlled trial. Dementia. 2021;20(6):2152–2169. doi: 10.1177/1471301220987374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]