Abstract

In advancing our understanding of tinnitus, some of the more impactful contributions in the past two decades have come from human brain imaging studies, specifically the idea of both auditory and extra-auditory neural networks that mediate tinnitus. These networks subserve both the perception of tinnitus and the psychological reaction to chronic, continuous tinnitus. In this article, we review particular studies that report on the nodes and links of such neural networks and their inter-network connections. Innovative neuroimaging tools have contributed significantly to the increased understanding of anatomical and functional connections of attention, emotion-processing, and default mode networks in adults with tinnitus. We differentiate between the neural correlates of tinnitus and those of comorbid hearing loss; surprisingly, tinnitus and hearing loss when they co-occur are not necessarily additive in their impact and, in rare cases, additional tinnitus may act to mitigate the consequences of hearing loss alone on the brain. The scale of tinnitus severity also appears to have an impact on brain networks, with some of the alterations typically attributed to tinnitus reaching significance only in the case of bothersome tinnitus. As we learn more about comorbid conditions of tinnitus, such as depression, anxiety, hyperacusis, or even aging, their contributions to the network-level changes observed in tinnitus will need to be parsed out in a manner similar to what is currently being done for hearing loss or severity. Together, such studies advance our understanding of the heterogeneity of tinnitus and will lead to individualized treatment plans.

Keywords: Tinnitus, Brain imaging, fMRI, MRI, PET, Neural networks, VBM, Hearing loss

Introduction

Tinnitus is the perception of sound in the absence of an external source, occurring in approximately 10–15% of the general population [1]. The most widespread form of tinnitus is chronic and subjective; the other forms are intermittent and temporary subjective tinnitus and, rarely, “objective” where another person can also hear the tinnitus sounds [2]. Clinicians also differentiate between a “neural” or primary tinnitus and somatic or secondary tinnitus, with the origin of tinnitus in the former being in the auditory pathways, while in the latter, the sounds are related to respiratory, musculo-skeletal, or vascular factors [3].

Subjective tinnitus, mostly chronic and continuous, has not been amenable to a mechanistic-level exploration in humans until recently. Much of what we know of the neural mechanisms of tinnitus is based on animal studies. With the advent of safe brain imaging in humans, some of the mystery of tinnitus is being revealed. These insights are often specific to human brain imaging and different from what has previously been understood from animal studies of tinnitus. For instance, having control groups matched for degree of hearing loss and sex is common in human brain imaging studies, but not so in animal studies [4, 5], and has allowed us to differentiate the correlates of tinnitus and hearing loss from hearing loss alone.

The perception of tinnitus varies among individuals, both in the number (one or more) and type of sounds (hissing, broadband noise, etc., and with respect to the sounds’ location) being perceived. Often, the determination of the neural sources or correlates of pitch is both to identify a mechanism (e.g., tonotopy) and to determine suitable therapy, such as masking, but pitch has not been found to correlate with severity of symptoms as yet. Few studies have attempted to correlate different types of tinnitus sounds with neuroimaging measures. In functional MRI (fMRI) studies where any perceptual aspects of tinnitus have been considered, it has primarily been modulating loudness of tinnitus sounds by external masking sounds [6, 7]. This modulation of the perceived loudness has been localized to inferior colliculus but may also be attributable to enhanced sound-evoked activity in the presence of the masker [7]. Unlike fMRI and PET studies, variations in the pitch of the percept have been more frequently studied using electroencephalography (EEG) [8] and magnetoencephalography (MEG) [9], but with equivocal findings.

Perceiving tinnitus, especially continuously, causes a psychological reaction in a proportion of individuals, which ranges from mild to severe [10, 11]. About 10–20% of individuals who report tinnitus seek medical help for their tinnitus-related impairments, and 1 to 3% indicate that their tinnitus is severe enough to cause significant disability [12, 13]. Such impairments include difficulties with sleeping, concentration, and communication. Anxiety and depression can also occur as part of this reaction [14, 15].

Unlike the perception of tinnitus, the reaction to it (often measured as varying severity of symptoms) has proven to be fertile ground for identifying neural correlates. To determine severity, any of the readily available validated questionnaires of tinnitus can be used. Of the available options, some prominent tinnitus severity questionnaires include the Tinnitus Questionnaire [16], Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [17], Tinnitus Functional Index [18], and Tinnitus Primary Function Questionnaire [19], among others. These measures, either in isolation or occasionally in conjunction, are commonly implemented by researchers and clinicians around the world. As one might imagine for a condition which is poorly understood, each measure has its own strengths and weaknesses. No single questionnaire appears to fully capture the entire experience of tinnitus—they are typically designed to be brief and it can be challenging to capture the multi-dimensional experience of tinnitus from just a few self-report questions. There is still, however, general agreement that tinnitus severity falls in a spectrum from mild to severe, and that this self-reported severity varies with each individual and possibly over time. Despite the highly heterogeneous and dynamic nature of tinnitus, there is general agreement on facets of daily life impacted by tinnitus, such as sleep, mood, and hearing difficulties, although there is no universal agreement on these facets across all questionnaires. A composite severity score, as obtained from the questionnaires, remains the most effective way to understand an individual’s handicap associated with the tinnitus experience and is likely to be the most effective endpoint in the development of therapies. Varying in terms of severity, subgroups within the tinnitus population may have different neural underpinnings. This heterogeneity may explain discrepant findings in literature regarding neural correlates and the efficacy of tinnitus therapies.

Other comorbid conditions of tinnitus are sound tolerance disorders (most commonly hyperacusis [20]), or more rarely, traumatic brain injury [21] or posttraumatic stress disorder [22, 23]. These may also contribute to the neural signatures of tinnitus, although the exact mechanisms remain unknown. While it could be argued that the strong correlation between these comorbid conditions and tinnitus severity could make them a component of tinnitus, there are reasons to think that these may be differentiated from severe symptoms, at least in some cases. For instance, some individuals may have high severity scores and yet may not have depression or anxiety (as is reported in Carpenter-Thompson et al. [24]). Correlates of hearing loss have been shown to differ from those of tinnitus in a number of studies, from our lab and others (e.g., Boyen et al. [25]; Schmidt et al. [26]). But in most cases, these conditions correlate strongly with severe tinnitus, making the task of the researcher and clinician difficult. We unpack some of these issues in this paper.

Findings from MRI and PET Studies

Anatomical Bases of Tinnitus

There has been considerable effort to understand neural plasticity of neural anatomy as it relates to tinnitus and hearing loss. Much of this research in humans has been conducted using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) to investigate plasticity in gray matter, and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to assess plasticity in white matter architecture.

VBM is an MRI technique which compares gray matter volume on a voxel-level between scans. Using a high-resolution structural T1-weighted image as input, gray matter volumes of either the whole brain or selected regions of interest (ROIs) are computed and assessed. White matter volume can also be compared using VBM, but this is done less commonly. VBM employs statistical tests across all voxels in the image to identify volume differences between the groups. Within-subjects, this can be conducted both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, or comparisons can be conducted across patient and control populations to investigate group differences. In addition to volume, VBM can also be used to observe changes or differences in gray matter thickness and concentration. VBM can be helpful in the study of tinnitus as it can demonstrate cross-sectionally how brain volume may differ between tinnitus and control groups in terms of gray matter. Longitudinally, VBM may be used to observe how brain volume may change over the course of tinnitus development or due to an intervention (e.g., Husain et al. [27]). VBM can be especially powerful if researchers have a specific hypothesis for a study, as it is possible to restrict the region of interest to specific regions of the brain.

DWI on the other hand uses the diffusion of water molecules to model the underlying organization and structure of neural white matter, while DTI is used to calculate metrics pertaining to the microstructural organization of white matter [28]. Within DTI, the most commonly assessed metric include axial and radial diffusivity (AD and RD respectively), the magnitude of water diffusion parallel to and perpendicular to the estimated white matter tracts respectively; fractional anisotropy (FA), the isotopic movement of water molecules in the strongest direction of movement in a given voxel; and mean diffusivity (MD), which is the average of magnitudes of diffusion in all directions within a voxel [29]. Reductions in FA and increases in RD can indicate reductions in white matter integrity. DWI also lends itself to more sophisticated analysis techniques, such as fixel-based analysis (FBA), which helps account for multiple fibers within a voxel by reporting metrics such as fiber density and fiber-bundle cross section [30]. While FBA is less commonly applied than other DWI metrics, there has been an increase in the use of FBA to study tinnitus populations in recent years. Diffusion imaging methods can help develop an understanding of how tinnitus may be associated with changes in the white matter architecture of the brain. However, these findings can sometimes be non-specific in their localization, given that many white matter tracts are quite long and widely connected.

Research has shown that hearing loss can have an impact on brain volume, especially in auditory regions, but also in extra-auditory regions of the brain. Peelle et al. [31] reported decreases in the right auditory cortex (but not in the left) volume associated with decreases in hearing acuity at 1, 2, and 4 kHz, and a non-significant correlation in the same direction in the right auditory cortex. Importantly, this relationship survived corrections for age-related morphological changes. Similarly, Eckert et al. [32] investigated gray matter volume as it related to a binary classification of low (< 2 kHz) or high (> = 2 kHz) frequency hearing loss, finding that high-frequency hearing loss was correlated with gray matter volume loss in bilateral auditory cortex. Again, this relationship was robust to corrections for healthy age-related changes in brain volume. The authors suggest that this highlights the primary auditory cortex as a particular region of interest when evaluating interventions for hearing loss. In a sample of participants with unilateral hearing loss, Yang et al. [33] found reduced volume in bilateral posterior cingulate gyrus, precuneus, and temporal gyri, as well as the right lingual and parahippocampal gyri, while Qi et al. [34] found reduced volume in the right temporal lobe and middle occipital gyrus associated with sensorineural hearing loss.

VBM studies of hearing loss have revealed gray matter differences with controls in non-auditory regions as well. Husain et al. [35] compared the gray matter volume of a group with hearing loss and tinnitus to a group with hearing loss without tinnitus, finding decreased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate and frontal regions, in addition to auditory regions (superior temporal gyri) for the hearing loss group without tinnitus compared to the group that also had tinnitus. This was a particularly interesting finding, suggesting a type of protective effect from the hyperactivity of the tinnitus, reducing the detrimental effects of hearing loss on brain volume. Similarly, Koops et al. [36] evaluated gray matter volume in a hearing loss group and a hearing loss-matched control group who also had tinnitus, finding that while atrophy was seen in both groups compared to controls, the hearing loss only group had more pronounced gray matter loss than the tinnitus group. Findings in VBM studies of hearing loss are not, however, always consistent. Boyen et al. [37] found both a hearing loss group and a hearing loss with tinnitus group to have increases, rather than decreases, in gray matter volume in superior and medial temporal lobes, entorhinal, and limbic regions compared to controls. They did find decreases associated with both patient groups in frontal and occipital lobes. Altogether, VBM studies of tinnitus and hearing loss have yet to ascertain a replicable pattern of findings, although all nearly point a differential effect of these conditions.

There is a similarly inconsistent pattern of findings in VBM studies of tinnitus in the context of normal hearing sensitivity [38]. In the first study of its kind, Mühlau et al. [39] found tinnitus-related decreases in the subcallosal area. Since then, tinnitus-related decreases in gray matter volume have been seen in the primary auditory cortex [37] and ventromedial prefrontal cortex [40]. Schecklmann et al. [41] found gray matter volume in the auditory cortex to be negatively correlated with TQ scores of tinnitus distress, suggesting a meaningful relationship between auditory cortex volume and tinnitus severity. However, null effects have also been reported [35, 42, 43]. In a large-scale study of 154 participants with tinnitus but no control group, Vanneste et al. [44] found that only the cerebellum showed statistically significant change in gray matter volume that could be attributed to tinnitus. A major source of complication in such studies has been inefficient control for hearing acuity. Given the independent effect of hearing loss on neural architecture, it can be challenging to extract the impact of tinnitus alone on gray matter volume. A recent meta-analysis accounted for this by investigating 931 participants from 15 studies divided into groups with and without tinnitus, and with and without hearing loss. They report a difference in gray matter volumes for the tinnitus group with normal hearing and the tinnitus group with hearing loss compared to hearing-matched controls. The tinnitus group with normal hearing demonstrated reduced gray matter volume in the left inferior temporal gyrus compared to hearing-matched controls. Interestingly, the tinnitus group with hearing loss showed increased gray matter volume in the lingual gyri and precuneus. Overall, the authors concluded that hearing loss appears to have a larger impact on gray matter architecture than does tinnitus, and that this should be a consideration in the design of future studies [45].

DTI studies of tinnitus and hearing loss have faced similar challenges, but some consistent findings have emerged. As per a comprehensive review [46], the auditory cortex and inferior colliculus have been most consistently shown to have reduced FA associated with hearing loss. Hearing loss has been shown to be associated with reduced FA in the lateral lemniscus and inferior colliculus [47, 48], as well as with reductions in FA in the trapezoid body, superior olivary nucleus, medial geniculate body, auditory radiation, and Heschl’s gyrus [47], all of which constitute the length of the auditory pathway. Hearing loss-related FA reductions have also been seen in association tracts such as the superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, anterior thalamic radiation, and uncinate fasciculus [35, 49], while increased MD in the uncinate fasciculus has also been noted [49].

FA, typically the most widely used diffusion metric used to evaluate tract integrity has been shown to have tinnitus-related reductions in the arcuate fasciculus [50], inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus [51, 52], corpus callosum [51–53], superior longitudinal fasciculus [51–53], inferior longitudinal fasciculus [51, 52], anterior thalamic radiation [51, 52], inferior colliculus [54], medial geniculate body [54], thalamic reticular nucleus [54], amygdala [54, 55], cingulum [53], forceps minor [52], and anterior and superior corona radiata [52]. Conversely, however, FA increases have also been seen in the auditory cortex [56], inferior colliculus [56], superior longitudinal fasciculus [57], superior and anterior corona radiata [57], internal capsule [57], and hippocampus [57]. A further source of complication is provided by studies investigating tinnitus-related FA which found no significant group differences [35, 58, 59]. These findings vary in how consistent and reproducible they are, with oppositional findings across different studies (e.g., the superior longitudinal fasciculus, where both increases [57] and decreases [51–53] in FA have been noted) making it challenging to hypothesize the exact relationship between these FA differences and the tinnitus condition.MD, which represents non-vectorized water diffusion, has been studied to a lesser extent, with Ryu et al. [58] finding tinnitus-related reductions in MD in superior, middle, and inferior temporal cortex, superior temporal sulcus, internal capsule, forinix stria terminalis, and sagittal stratum, and Chen et al. [53] found increased MD in the body of the corpus callosum. Koops et al. [60] found increased MD in the MD in the acoustic radiation of those with tinnitus and hearing loss compared to healthy controls. Overall, while the pattern of findings appears largely heterogenous, there are some useful takeaways from this body of work. Khan et al. [52] used MD as a supplementary measure to FA, finding considerable overlap between regions of reduced FA and increased MD in tinnitus participants. We can have added confidence that regions with this pattern of findings (reduced FA and increased MD) may have disrupted fiber tracts, as diffusion is less vectorized in a given direction. Using FBA, Koops et al. [60] found tinnitus-related atrophy in a section of the left acoustic radiation, near the medial geniculate body, overlapping with observed increases in MD, as described above, and collectively these findings may suggest myelination. This finding was seen in a group with both tinnitus and hearing loss compared to controls, and not in a hearing loss-only group or in when the tinnitus group and hearing loss-only group were compared. Since this is the only published manuscript to use this technique in tinnitus research, we have not yet established how well this finding replicates, but this finding suggests that further work is needed in this area.

Altogether, results suggest that hearing loss has a larger impact on neural plasticity than does tinnitus, although the exact plasticity that occurs appears to be different when hearing loss alone occurs compared to when hearing loss is comorbid with tinnitus [52, 54, 57]. This is analogous to findings in gray matter using VBM, where there appears to be almost a protective effect of tinnitus on brain volume loss. This may be associated with the specific plasticity seen in those with tinnitus and hearing loss in diffusion imaging studies, although the few studies to have implemented both techniques have failed to find overlap [35, 53]. This also leads to methodological considerations—many DWI studies of tinnitus do not adequately account for hearing loss or lack an appropriate control group. Furthermore, while the subject groups are age-matched in many cases, age is not regressed out of the statistical model. Both aging and hearing loss are known to impact FA values, and so may be affecting some of the results reported. One DWI metric rarely employed in the field of tinnitus research is fiber tractography. Tractography maps the white matter architecture of the brain and allows for close inspection of node-to-node connectivity. Using tractography, Crippa et al. [55] reported stronger connectivity between the amygdala and auditory cortex in a tinnitus group compared to a control group, while Khan et al. (2021) report altered structural connectivity metrics in a tinnitus and hearing loss group compared to a control group in the precuneus and the temporal lobes. Interestingly, Khan et al. [52] did not find differences between controls and a hearing loss only, or tinnitus-only groups, suggesting that their findings are specific to tinnitus when comorbid with hearing loss. These results hint at an underlying biological basis for findings in functional connectivity, discussed below.

Functional Bases of Tinnitus

EEG studies of tinnitus have preceded those using positron emission tomography (PET) and fMRI. EEG allows for quieter presentation of sounds and provides more detailed analysis of the timeline of activation but is poorer in terms of spatial resolution. Tinnitus correlates from EEG studies have been noted in the form of both evoked responses and bands of waveforms from spectral analysis. The evoked responses related to tinnitus and noted in several studies have been of the N1/P2 complex, which occurs within 100–200 ms after the sound presentation, often a 1 kHz tone. Here, the evoked potentials are estimated to be decreased in individuals with tinnitus compared to controls [61]. The effect of hearing loss is often not discussed in these articles and the findings remain equivocal [62]. Similar to EEG, MEG studies have focused on M100/M200 complex with similar unreplicated findings. Spectral analyses, especially of spontaneous activity, have proven useful in differentiating large groups of patients from controls [63]. The focus of this review being on fMRI and PET studies, we refer the reader to previously published comprehensive reviews of the techniques of EEG and MEG and their findings to a comprehensive review by Adjamian [64], and a forthcoming one in this same special issue of JARO.

Task-Based fMRI and PET

Functional MRI identifies blood-oxygenated level-dependent signal in the brain, a correlated of neuronal activity. PET imaging, as used in tinnitus studies, employs a radioactive tracer to determine blood flow either in a task condition and compares it to a rest or control condition, or is used in a rest condition exclusively. Task-based fMRI and PET studies have been used primarily to contrast masked conditions (when tinnitus is not perceived due to the external sound being played) and an unmasked condition. The first study of this type showed that the conditions of perceiving or not perceiving their own tinnitus resulted in different brain regions being engaged [65]. Both sound-based masking and lidocaine conditions were used to momentarily suppress the perception of tinnitus, and when contrasted with the perception of tinnitus condition, similar regions were observed to be engaged. These regions were the superior and middle frontal gyri, middle temporal gyrus, amygdala, anterior cingulate, and superior parietal lobule.

Approximately 10 years later, Leaver and colleagues designed a study, somewhat similar to the one by Mirz and colleagues by employing sounds that matched the tinnitus frequency and in a separate set were an octave above and below the matched frequency [40]. They used fMRI and compared the activation in the tinnitus group against a control group of subjects. They found an increased response in the auditory cortices and in the nucleus accumbens located in the ventral striatum, leading the authors to conclude a disruption of the auditory-limbic connections, although this study did not employ functional connectivity measures.

Another manner in which task-based fMRI studies have been useful has been in the employment of affective stimuli to identify any differences in emotion-processing between tinnitus and control groups. In a companion study to their 2000 paper, Mirz et al. presented 24 unpleasant sounds that mimicked tinnitus to healthy volunteers without tinnitus [66]. They found that primary and secondary auditory processing centers were more active compared to a null condition, contrasting with what they found in the tinnitus study (i.e., a lack of such activation in the study with tinnitus participants). However, there was a similar engagement of attention processing centers in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior and middle frontal cortex, and inferior parietal cortex as well as in the limbic areas.

In a series of two studies, Carpenter-Thompson et al. [24, 67] used sounds from the international affective digital sounds (IADS [68]) to directly probe the engagement of emotio-processing areas of the brain. In the first study, individuals with mild tinnitus and hearing loss were compared with hearing loss and normal hearing controls in the processing of unpleasant, pleasant, and neutral sounds, with similar arousal levels [67]. The tinnitus group had greater engagement of the bilateral parahippocampus and right insula compared to the non-tinnitus group, and left parahippocampus compared to hearing loss controls for pleasant relative to neutral sounds. But more interestingly, in the focused analysis of the amygdala, there was an increased response in the right amygdala for the normal hearing controls when processing affective sounds compared to neutral sounds; such engagement was missing both from the tinnitus and the hearing loss groups. However, the behavioral responses captured showed that there was no difference in ratings of sounds, but there was a difference in timing—those with hearing loss and tinnitus were as fast as those in the hearing control group; it was the control group with only hearing loss that was the slowest. In a follow-up study, the investigators contrasted a group with mild tinnitus with a group with more bothersome tinnitus [24]. Here, the bothersome group showed robust activation in bilateral amygdala, whereas the mild tinnitus group did not. Instead, they showed greater engagement of the insula and the frontal cortices. Both groups, however, completed the task and had similar ratings of the stimuli. This led the authors to propose the idea of top-down, cognitive regulation of emotion processing (linked to emotional regulation in general) that facilitates habituation and leads to milder tinnitus.

Resting-State fMRI and PET

Resting-state fMRI and PET have been more fruitful than task-based fMRI in delineating the neural bases of tinnitus. In resting-state studies, the participant is asked to focus on a “ + ” on screen or to keep their eyes closed; they are instructed to let their mind wander and are given no specific goal or task to focus on. Analysis ascertains correlated spontaneous activity between two or more brain regions, termed as “functional connectivity.” Whereas we might assume a functional connectivity difference between people with tinnitus and controls due to the differences in their “rest” states (i.e. perceiving the tinnitus sound vs. not), it should be considered the fMRI is a loud procedure, and it is not clear how much people with tinnitus perceive their tinnitus over the noise of the scanner. This should be considered when designing future resting-state fMRI studies, as some people with tinnitus may perceive the sound in the scanner, while others may not. If we assume, however, that this difference in resting state is due to the “trait” of having chronic continuous tinnitus, such studies are conducive to revealing differences between groups without the need for complicated experimental setups [69]. Another factor to consider is whether tinnitus is considered as a state or a trait while the images are being acquired. While resting-state studies are typically used to investigate trait conditions rather than state, tinnitus is a unique experience which can be investigated as either a state or a trait. In this regard, if tinnitus is considered a trait, masking by the scanner noise may have a lesser impact on resting-state images acquired, but if considered a state, masking matters more. This should be considered when designing future resting-state fMRI studies, as some people with tinnitus may perceive the sound in the scanner, while others may not. For these reasons, it is important for researchers in this area to begin collecting this information from participants, something that we have started to do in our own lab [70].

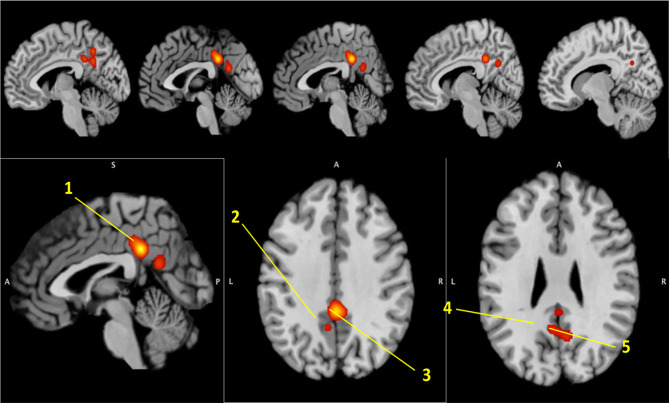

Several recent reviews have evaluated amalgamated evidence obtained from fMRI studies of tinnitus [38, 71]. Overall evidence suggests resting-state alterations primarily in the default-mode, auditory, and attention resting-state networks, as well as the visual network. Specific findings, however, such as exact loci of these alterations and directionality of the results (whether connectivity increases or decreases) often show conflicting or oppositional findings and lead to inconsistent conclusions. One may suspect that this might be an inherent flaw within the tool itself, but recent work has shown resting-state fMRI (specifically seed-to-seed resting state functional connectivity) to be a robust measure, both within people with tinnitus and controls, on both a short-term as well as a long-term [70]. This naturally suggests another source for this variability, which is commonly thought to be both the inherent heterogeneity in the tinnitus population, as well as variance in the study populations due to poor controls or insufficient power. Various neuroimaging studies of tinnitus do not sufficiently control for comorbid factors of the tinnitus experience (such as hearing loss, aging, or other hearing conditions such as hyperacusis) and often contain relatively small sample sizes. PET studies were one of the first brain imaging studies to identify large-scale neural networks subserving tinnitus. Over the years, the number of PET studies has been overtaken by the more ubiquitous fMRI tool, but nevertheless, the pioneering PET studies have paved the way for our understanding of tinnitus in humans. The initial rest-based studies using PET often had few participants or focused on specific regions such as the auditory cortex. A few studies attempted to estimate any asymmetry in regional cerebral blood flow measures (estimate of neural activity) in the auditory cortices [72–75] but found some contradictory results. While earlier studies noted an asymmetry in the auditory cortex regional cerebral blood flow in tinnitus patients, Geven et al. [73] also noted a similar asymmetry in controls. Thus, a promising lead on hyperactivity in the auditory cortex as a neural correlate of tinnitus did not pan out. In recent work from our lab [76], we estimated the global perfusion in the brain of 10 tinnitus patients and controls using arterial spin labeling, an analog of PET’s regional cerebral blood flow measure using MRI. The global cerebral blood flow was found to be reduced in tinnitus, with this reduction correlated with severity of tinnitus symptoms. A ROI analysis also saw reduction in the blood flow in the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex, but not in the posterior superior temporal gyrus or the dorsomedial frontal gyrus, other regions tested, in the tinnitus group compared to controls. This reduction was separately correlated with both hearing loss and tinnitus severity. In an innovative effort to integrate both structural and functional bases of tinnitus, a recent meta-analysis implemented activation likelihood estimation (ALE) on a total of 17 resting-state fMRI and 7 VBM studies of tinnitus [77]. The authors found a significant cluster comprising the posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus (Fig. 1 in this paper). This led the authors to conclude that tinnitus likely impacts a wide range of neural connections, and is not simply limited to auditory processing regions.

Fig. 1.

Regions identified by corrected ALE. Note: 1, cingulate gyrus; 2, precuneus; 3, cingulate gyrus/precuneus; 4, posterior cingulate/precuneus; 5, posterior cingulate/precuneus. From Moring JC, Husain FT, Gray J, Franklin C, Peterson AL, Resick PA, Fox PT (2022) Invariant structural and functional brain regions associated with tinnitus: A meta-analysis. PloS ONE 17(10):e0276140; Figure 2 [77]

Networks of Tinnitus

Often studies, perhaps in service of expediency, ignore one or more of the confounding factors (e.g., not controlling for age or hearing loss) or not having sufficient control groups (e.g., comparing a group with both tinnitus and hearing loss with normal hearing controls), or they may err on the side of selecting a homogenous group for better interpretable findings, with the result that such findings (e.g., of mild, lateralized tinnitus in adults with normal hearing thresholds) are often not generalizable to the larger tinnitus population. The solution to this conundrum necessarily lies in the execution of multiple studies and collation of data thereof. In a meta-analysis of resting-state fMRI and VBM studies [78], 17 resting-state fMRI and 8 VBM reports of tinnitus-associated regional alterations were analyzed using activation likelihood estimation. The authors found that the only regions that survived the threshold for the activation likelihood estimation (ALE) after multiple comparison corrections were the posterior cingulate gyrus and precuneus. Additional regions within auditory and cognitive processing networks were only identified at a looser, uncorrected threshold. This data-driven approach underscores both that tinnitus correlates are often networks that span the brain and are not localized to within the auditory pathways, and that such approaches are necessary to handle the vast heterogeneity of the patient population. Fortunately, the field of brain imaging and tinnitus has matured enough and has produced sufficient robust studies such that these data-driven approaches are feasible.

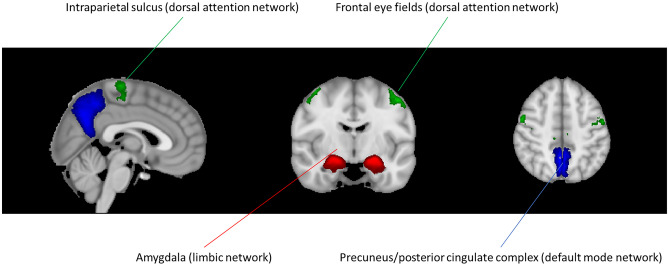

Consolidating the pieces of evidence across functional and anatomical studies, using varying methodology has revealed not only what networks are possibly mediating tinnitus, but also which networks do not. It becomes evident that, surprisingly, the auditory cortices and their connections do not play as prominent a role in mediating tinnitus as was originally hypothesized. Instead, inter- and intra-network connectivity in the attention network (primarily dorsal, comprising of frontal eye fields and intraparietal sulcus), the emotion processing network (consisting of nodes in the limbic system such as the amygdala, parahipppocampal gyrus, and insula), the default mode network (posterior cingulate, including the precuneus, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the angular gyrus/lateral parietal cortex), and more recently the salience network (anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex) appear to be significantly altered in the presence of tinnitus.

The dorsal attention network (DAN) and default mode network (DMN) are seen to be anticorrelated, in that when activity in one of the networks increases, activity in the other is seen to decrease [79]. In tinnitus, most fMRI investigations into these networks suggest decreased DMN activity at rest and increased DAN activity compared to controls [38, 69]. As described earlier, this may suggest the cognitive demands of attending to the tinnitus percept as being similar to processing a task. A possible biological correlate for this finding may be seen in tractography studies where alterations in precuneus structural connectivity have been reported [52]. However, the salience network may also be involved in this process. The salience network is heavily involved in the orienting and maintenance of attention to salient stimuli [79], and its disruption has been suggested as being vital in bringing the tinnitus percept to consciousness [80]. As noted in a review [81], increased activity in the anterior cingulate has been noted in fMRI, PET, and EEG studies of tinnitus. Using a novel resting-music fMRI paradigm, Shahsavarani et al. [82] found interactive DAN-DMN-salience alterations in connectivity for people with tinnitus compared to controls, suggesting that the relationship previously described may be moderated by salience network connectivity. In their conceptualization of tinnitus and its related distress, De Ridder et al. [83] describe a triple-network tinnitus model, wherein alterations in connectivity between the salience, DMN, and central executive networks underlie bothersome or severe tinnitus. If processing of the tinnitus percept can be considered a “task” (requiring cognitive or neural resources), we might expect a differentiated state between someone who has tinnitus and someone who does not when evaluating fMRI activity. Indeed, the strongest evidence suggests altered connectivity within the default mode network (typically most active at rest), as well as between the default mode and attentional or auditory networks. The default mode network is seen to be heavily involved in organizing cognitive resources [69], and a consistent increase in activity in this network could underlie some of the cognitive challenges faced by people with tinnitus, lending a behavioral explanation to these findings.

Alterations to Tinnitus Networks

Typically, the alterations to networks of established tinnitus have been due to interventions or other disruptions of the tinnitus signal. In the earlier days, this was done to contrast the tinnitus condition with the non-tinnitus condition, achieved by say a masker or by an agent such as lidocaine [65]. In the more recent past, longitudinal assessment of changes to neural networks over the period of the intervention has allowed us to better understand the evolution of short-term habituation to tinnitus and its neural correlates. In this section, we highlight a few treatment studies where the assessment tool was either fMRI or PET and which exemplify how changes to neural networks may follow the reduction in tinnitus handicap.

In a recent PET study employing hearing aids as an intervention, the authors used resting-state PET to measure differences in changes over the period of interventions in both individuals with tinnitus and hearing loss and a control group with hearing loss alone [84]. The glycolytic metabolism measured indicated increases in the left orbitofrontal cortex, right temporal lobe, and right hippocampus, and decreases in glycolytic metabolism in the left cerebellum and inferior parietal lobe within the tinnitus group, over the 6-month intervention, mirroring a decline in tinnitus handicap. In contrast, the hearing loss control group did not show any significant metabolic changes over the same period of intervention. An important consideration for this study is that hearing aids are intended for restoration and improvement of hearing, and that this amplification of external sounds may serve to mask the internal tinnitus percept. In order to better generalize these findings, additional studies, particularly replications with larger sample sizes, are needed to establish an understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

In a series of articles using the Heidelberg music therapy [85, 86], cortical reorganization was seen in the anatomical and functional connectivity changes of several neural networks, mirroring a decline in tinnitus handicap. The intervention consists of nine consecutive 50-min sessions of individualized music-based therapy that occur over 1 week. The changes in the gray matter were noted in precuneus (part of the default mode network), medial superior frontal areas, and in the auditory cortex [85]. The research group also found that the intervention resulted in increased default-mode activity by about 25%.

Recent work has shown the efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in reducing tinnitus severity [87–89]. MBCT is a form of psychotherapy which uses a combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness meditative practices to help clients better deal with their stressors. In the first study of this type, Roland et al. [90] showed robust declines in tinnitus handicap after an 8-week regimen of mindfulness-based stress reduction classes. A separate analysis of the resting state fMRI data showed increased functional connectivity of the attention network but not the default network when the post-treatment measures were compared to the baseline measures. In a study from our lab [27], we conducted a similar study but using a stereotypical MBCT instead of a customized mindfulness-based stress reduction as in the Roland et al. [90] study, with somewhat more elaborate analyses. Fifteen participants underwent audiological and behavioral screening (establishing a baseline) prior to MBCT, in addition to three subsequent assessments: pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up (8 weeks after completion of training). Eight participants also underwent three MRI tests at pre- and post-intervention, and at follow-up. In terms of self-reported questionnaires, we found both statistically and clinically significant reductions in tinnitus distress over the course of the intervention and at the follow-up period. We found significant decreases in functional connectivity among the DMN, salience network, and amygdala across the intervention, but no differences were seen in connectivity with seeds in the DAN and the rest of the brain. Furthermore, only the connectivity between the ROIs and the amygdala, DAN, and fronto-parietal network significantly predicted TFI [91]. These results point to a mostly differentiated landscape of functional brain measures related to tinnitus severity on the one hand and MBCT on the other. However, overlapping results of decreased amygdala connectivity with parietal areas and the negative correlation between amygdala-parietal connectivity and TFI are suggestive of a brain imaging marker of successful treatment.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive method which uses electromagnetic energy to induce electrical currents in the brain and has been found to provide temporary relief to a certain fraction of the tinnitus population [92]. Poeppl et al. [93] conducted a VBM study of rTMS, where stimulation was focused on the left dorsolateral prefrontal and temporal cortex, investigating volume changes in both responders and non-responders. The authors observed gray matter decreases over the period of the intervention in responders in the left dorsolateral prefontal cortex (DLPFC), left operculo-insular cortex, and right inferior temporal cortex, but not in the brains of the non-responders. The authors further noted a lack of effect of age, sex, hearing loss, or tinnitus features such as laterality, duration, and severity at baseline on these changes. These findings may suggest a potential mechanism for tinnitus relief provided by rTMS.

Overall, there are currently too few treatment studies whose effectiveness has been assessed by resting-state fMRI methods to identify any consistent patterns of findings across treatments that could be attributed to alterations in tinnitus networks. More studies are needed in this area to develop a wider perspective on the neural impacts of these treatments. Based on findings thus far, we hypothesize that were a reliably effective treatment to be developed, the largest impacts would likely on the auditory network, and any network that may underlie the perception of tinnitus.

Is There a Benefit to Tinnitus in Some Cases?

A surprising fact emerging over the past several years has been the lack of consistent findings (and, sometimes, null findings) regarding anatomical changes, either in the gray matter or white matter, when hearing loss is accounted for. This is striking when we contrast tinnitus-related network alterations with those of hearing loss, especially when we focus on anatomy. One interpretation of such lack of changes is that neuroanatomical changes due to mild tinnitus (having a chronic sound) may be oppositional to those due to hearing loss (sensory deprivation), either in maintaining gray matter or neuronal tracts. This is, nevertheless, not the only explanation, but it points to directions for future research and to unpacking an unexpected benefit to tinnitus persistence.

In the case of mild tinnitus, the response time to processing affective sounds is faster than when considering hearing loss alone, and more closely aligning with those in the control population with normal hearing sensitivity [67]. Recent behavioral studies have noted a cognitive benefit that can be attributed to having tinnitus in addition to hearing loss over those with hearing loss alone, at least in certain ethnic groups [94]. Studies of speech-in-noise performance had previously noted a reduced ability in individuals with tinnitus [95]. More recent studies have shown that this is not necessarily the case [96] and the effect, if any, remains small once hearing loss is accounted for [97]. Tai and colleagues [98] noted that in a tinnitus group with normal hearing, their performance on speech-in-noise task was significantly correlated with reduced gray matter volumes in the left cerebellum and left superior temporal gyrus; no such association was noted in a control group without tinnitus and both groups had comparable accuracy.

However, these studies did not report on severity of tinnitus, or did not include subgroups with more bothersome tinnitus; the latter may have an effect that may be markedly different than that of mild tinnitus in cognitive tasks.

Our own brain imaging work has shown that there is an engagement of the attention system in individuals with mild tinnitus and hearing loss that may be modality specific [99] and still present when hearing loss was accounted for [100]. Areas in the superior and dorsomedial frontal cortex and the intraparietal sulcus are implicated in these differences, primarily attributed to the case of divided attention occurring in such tasks due to chronic tinnitus and the need to process externally relevant sounds or visual stimuli. Interestingly, there were no differences in performance measures of accuracy or response time in either of the studies, despite a difference in engagement of brain regions when mild tinnitus group was compared to hearing loss alone or normal hearing control groups. This suggests that at least in the case of mild tinnitus and hearing loss, overt performance may not differ from those of control groups, and in some cases may be better, but the brain regions subserving such behavior may differ. We have attributed some of such benefits in the case of mild tinnitus to better cognitive control of emotions, leading to better habituation to chronic tinnitus [69, 101]. Future large-scale studies focusing on more severe symptoms of tinnitus are necessary to elucidate the burdens on this tinnitus subgroup and their associated neural mechanisms.

Limitations

Despite advances in the understanding of tinnitus, driven by technological innovations in neuroimaging, there remain several limitations to tinnitus studies discussed in this article that need to be addressed. These limitations contribute to the discrepant findings and delay a better understanding of the neural mechanisms and subsequently of the therapies needed to help patients with bothersome tinnitus.

One major limitation is study sample sizes as discussed earlier, but also the limit on external validity of findings from these studies due to selection bias—participants in these studies largely tend to be well-educated, Caucasian or white ethnicity, medium-to-high socio-economic status (SES) individuals, and studies are typically conducted in college towns or around college campuses. The lack of racial, ethnic, geographic, and SES diversity severely limit researchers’ ability to apply their findings to the wider tinnitus population. This also impacts how treatment options may affect interventions and how perceived handicap is assessed.

As we have begun to better understand the interaction between cognitive abilities and chronic tinnitus, a gap in the field is the lack of rigorous, widespread neuropsychological testing to assess such cognitive abilities beyond psychoacoustic tasks. Recent studies [102] have begun to remedy this oversight. More such studies are needed, extending beyond the normal hearing subgroup of the Sharma et al. study and linking to brain imaging correlates.

Barring a few exceptions, human imaging studies have mostly not focused on the subcortical structures in the central auditory pathways that may be the originating sources of tinnitus [103]. Here, the large body of evidence comes from mostly rodent studies of tinnitus [104, 105], which drives the conventional scientific wisdom on how we view the origin of tinnitus. A large factor in the lack of understanding of the brain bases of tinnitus also stems from some fundamental differences between animal and human studies [4, 5]. Typically, animal studies do not account for the degree of hearing loss and do not include representation from both sexes; this is as opposed to human studies, where hearing loss is comorbid with up to 90% of the population and both men and women report having tinnitus in somewhat equal numbers [106].

Because this review has largely ignored animal studies and EEG/MEG studies, it has also not fully considered the role of auditory cortex or the thalamus and processes such as gating of sensory input. As a recent review [107] makes clear, there is value to further consideration of these sources of tinnitus, which may also serve as a bridge between animal and human studies.

Conclusion

A valid question to ask is, do we know more about the neural bases and mechanisms of tinnitus than we did before human brain imaging became ubiquitous in the study of tinnitus? The answer is a resounding yes. Brain imaging has allowed us to have an expansive, holistic view of tinnitus beyond finding its correlate within one brain region; we can now non-invasively view the entire brain and associate the activity and connectivity of these region with particular symptoms or composite score of the handicap.

Findings in the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex complex highlight both the progress made and the challenges we continue to face in the study of the neural bases of tinnitus. In cross-sectional studies [26, 108], intervention studies [85, 91], a perfusion study [76], diffusion and tractography investigations [52], and a quantitative meta-analysis of cross-sectional resting state and VBM studies [77], these two regions were seen to be altered either in terms of their neural organization or in their connectivity with other networks and regions in the brain. However, while this has been the most consistent finding in this field, it is not universally replicated (e.g., Roland et al. [90]), which does not lend itself to a coherent narrative about neural bases of tinnitus. Nevertheless, the preponderance of evidence suggests a direct involvement of these regions, as part of the default mode network, or possibly in their direct connection with the dorsal attention network.

Currently, the most consistent findings of neural patterns associated with tinnitus have been observed when using the tool of resting-state fMRI. Results in structural imaging literature appear to be inconsistent, possibly due to the more profound impact of any comorbid hearing loss. Given that the most common findings in resting-state fMRI studies of tinnitus show alterations in intra- and inter-network functional connectivity in the limbic, dorsal attention, and default mode networks of people with tinnitus, we hypothesize that these networks would also be likely candidates for exhibiting alterations in activity and connectivity patterns if an individual with tinnitus underwent effective treatment (Fig. 2). As evidence accumulates, we will have a multitude of studies explaining a particular subgroup and will be able to consistently delineate the neural mechanisms that subserve several such subgroups of tinnitus. The mechanisms of tinnitus appear to be manifold, akin to the neural correlates which may be multiple, and both are likely influenced by comorbid conditions like hearing loss and depression. Overall, a holistic explanation of tinnitus (both percept and reaction) is more attainable using the neural measures and correlates afforded to us by brain imaging studies. Even if mechanisms of tinnitus were to be completely mapped, brain imaging will continue to play an important role in the development and testing of effective treatments for tinnitus, especially with potential future technological breakthroughs in imaging.

Fig. 2.

Alterations in functional networks when tinnitus is present. These regions (and their networks) have been observed to show the most consistent alterations of functional connectivity in the presence of tinnitus. We hypothesize that these same regions would show alterations of functional connectivity as a results of effective treatment due to significant changes in tinnitus distress

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jarach CM, Lugo A, Scala M, et al. Global prevalence and incidence of tinnitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(9):888–900. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry JA, Griest S, Austin D, Helt W, Gordon J, Thielman E, Carlson K. Tinnitus screener: results from the first 100 participants in an epidemiology study. Am J Audiol. 2016;25(2):153–160. doi: 10.1044/2016_AJA-15-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry JA. “Measurement” of tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(8):e276–e285. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggermont JJ. Hearing loss, hyperacusis, or tinnitus: what is modeled in animal research? Hear Res. 2013;295:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lobarinas E, Hayes SH, Allman BL. The gap-startle paradigm for tinnitus screening in animal models: limitations and optimization. Hear Res. 2013;295:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melcher JR, Sigalovsky IS, Guinan JJ, Jr, Levine RA. Lateralized tinnitus studied with functional magnetic resonance imaging: abnormal inferior colliculus activation. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83(2):1058–1072. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melcher JR, Levine RA, Bergevin C, Norris B. The auditory midbrain of people with tinnitus: abnormal sound-evoked activity revisited. Hear Res. 2009;257(1–2):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wienbruch C, Paul I, Weisz N, Elbert T, Roberts LE. Frequency organization of the 40-Hz auditory steady-state response in normal hearing and in tinnitus. Neuroimage. 2006;33(1):180–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mühlnickel W, Elbert T, Taub E, Flor H. Reorganization of auditory cortex in tinnitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95(17):10340–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning C, Thielman EJ, Grush L, Henry JA. Perception versus reaction: comparison of tinnitus psychoacoustic measures and Tinnitus Functional Index scores. Am J Audiol. 2019;28:174–180. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJA-TTR17-18-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyler R, Coelho C, Tao P, Ji H, Noble W, Gehringer A, Gogel S. Identifying tinnitus subgroups with cluster analysis. Am J Audiol. 2008;17(2):S176–S184. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/07-0044). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochkin S, Tyler R. Tinnitus treatment and the effectiveness of hearing aids: hearing care professional perceptions. Hear Rev. 2008;15(13):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unterrainer J, Greimel KV, Leibetseder M, Koller T. Experiencing tinnitus: which factors are important for perceived severity of the symptom? Int Tinnitus J. 2009;9:130–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartels H, Middel BL, van der Laan BF, Staal MJ, Albers FW. The additive effect of co-occurring anxiety and depression on health status, quality of life and coping strategies in help-seeking tinnitus sufferers. Ear Hear. 2008;29(6):947–956. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181888f83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husain FT. Perception of, and reaction to, tinnitus: the depression factor. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2020;53(4):555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallam RS, Jakes SC, Hinchcliffe R. Cognitive variables in tinnitus annoyance. Br J Clin Psychol. 1988;27(3):213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1988.tb00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122(2):143–148. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, Stewart BJ, Abrams HB, McArdle R, et al. The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2012;33(2):153–176. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyler R, Ji H, Perreau A, Witt S, Noble W, Coelho C. Development and validation of the tinnitus primary function questionnaire. Am J Audiol. 2014;23(3):260–272. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-13-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cederroth CR, Lugo A, Edvall NK, Lazar A, Lopez-Escamez JA, Bulla J, Gallus S. Association between hyperacusis and tinnitus. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2412. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clifford RE, Ryan AF. The interrelationship of tinnitus and hearing loss secondary to age, noise exposure, and traumatic brain injury. Ear Hear. 2022;43(4):1114–1124. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moring JC, Resick PA, Peterson AL, Husain FT, Esquivel C, Young-McCaughan S, Granato E, Fox PT, STRONG STAR Consortium Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder alleviates tinnitus-related distress among veterans: a pilot study. Am J Audiol. 2022;31(4):1293–1298. doi: 10.1044/2022_AJA-21-00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moring JC, Peterson AL, Kanzler KE. Tinnitus, traumatic brain injury, and posttraumatic stress disorder in the military. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25:312–321. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9702-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carpenter-Thompson JR, Schmidt S, McAuley E, Husain FT. Increased frontal response may underlie decreased tinnitus severity. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyen K, de Kleine E, van Dijk P, Langers DR. Tinnitus-related dissociation between cortical and subcortical neural activity in humans with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss. Hear Res. 2014;312:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt SA, Akrofi K, Carpenter-Thompson JR, Husain FT. Default mode, dorsal attention and auditory resting state networks exhibit differential functional connectivity in tinnitus and hearing loss. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Husain FT, Zimmerman B, Tai Y, Finnegan MK, Kay E, Khan F, Gobin RL. Assessing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy intervention for tinnitus using behavioural measures and structural MRI: a pilot study. Int J Audiol. 2019;58(12):889–901. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2019.1629655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baliyan V, Das CJ, Sharma R, Gupta AK. Diffusion weighted imaging: technique and applications. World J Radiol. 2016;8(9):785–789. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v8.i9.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soares JM, Marques P, Alves V, Sousa N. A hitchhiker’s guide to diffusion tensor imaging. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:31. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raffelt DA, Tournier JD, Smith RE, Vaughan DN, Jackson G, Ridgway GR, Connelly A. Investigating white matter fibre density and morphology using fixel-based analysis. Neuroimage. 2017;144:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peelle JE, Troiani V, Grossman M, Wingfield A. Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension. J Neurosci. 2011;31(35):12638–12643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2559-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eckert MA, Cute SL, Vaden KI, Kuchinsky SE, Dubno JR. Auditory cortex signs of age-related hearing loss. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2012;13:703–713. doi: 10.1007/s10162-012-0332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang M, Chen HJ, Liu B, Huang ZC, Feng Y, Li J, Teng GJ. Brain structural and functional alterations in patients with unilateral hearing loss. Hear Res. 2014;316:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi R, Su L, Zou L, Yang J, Zheng S. Altered gray matter volume and white matter integrity in sensorineural hearing loss patients: a VBM and TBSS study. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(6):e569–e574. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Husain FT, Medina RE, Davis CW, Szymko-Bennett Y, Simonyan K, Pajor NM, Horwitz B. Neuroanatomical changes due to hearing loss and chronic tinnitus: a combined VBM and DTI study. Brain Res. 2011;1369:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koops EA, de Kleine E, van Dijk P. Gray matter declines with age and hearing loss, but is partially maintained in tinnitus. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21801. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78571-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyen K, Langers DR, de Kleine E, van Dijk P. Gray matter in the brain: differences associated with tinnitus and hearing loss. Hear Res. 2013;295:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahsavarani S, Khan RA, Husain FT. Tinnitus and the brain: a review of functional and anatomical magnetic resonance imaging studies. Perspect ASHA SIGs. 2019;4(5):896–909. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mühlau M, Rauschecker JP, Oestreicher E, Gaser C, Röttinger M, Wohlschläger AM, Simon F, Etgen T, Conrad B, Sander D. Structural brain changes in tinnitus. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(9):1283–1288. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leaver AM, Renier L, Chevillet MA, Morgan S, Kim HJ, Rauschecker JP. Dysregulation of limbic and auditory networks in tinnitus. Neuron. 2011;69(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schecklmann M, Lehner A, Poeppl TB, Kreuzer PM, Rupprecht R, Rackl J, Burger J, Frank E, Hajak G, Langguth B, Landgrebe M. Auditory cortex is implicated in tinnitus distress: a voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;218:1061–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0520-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landgrebe M, Langguth B, Rosengarth K, Braun S, Koch A, Kleinjung T, May A, de Ridder D, Hajak G. Structural brain changes in tinnitus: grey matter decrease in auditory and non-auditory brain areas. Neuroimage. 2009;46(1):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melcher JR, Knudson IM, Levine RA. Subcallosal brain structure: correlation with hearing threshold at supra-clinical frequencies (> 8 kHz), but not with tinnitus. Hear Res. 2013;295:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanneste S, Van De Heyning P, De Ridder D. Tinnitus: a large VBM-EEG correlational study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0115122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makani P, Thioux M, Pyott SJ, van Dijk P. A combined image- and coordinate-based meta-analysis of whole-brain voxel-based morphometry studies investigating subjective tinnitus. Brain Sci. 2022;12(9):1192. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12091192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarabichi O, Kozin ED, Kanumuri VV, Barber S, Ghosh S, Sitek KR, Reinshagen K, Herrmann B, Remenschneider AK, Lee DJ. Diffusion tensor imaging of central auditory pathways in patients with sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(3):432–442. doi: 10.1177/0194599817739838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang L, Zheng W, Wu C, Wei X, Wu X, Wang Y, Zheng H. Diffusion tensor imaging of the auditory neural pathway for clinical outcome of cochlear implantation in pediatric congenital sensorineural hearing loss patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0140643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Y, Wang J, Wu C, Wai Y, Yu J, Ng S. Diffusion tensor imaging of the auditory pathway in sensorineural hearing loss: changes in radial diffusivity and diffusion anisotropy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(3):598–603. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rigters SC, Cremers LG, Ikram MA, van der Schroeff MP, De Groot M, Roshchupkin GV, Vernooij MW, Niessen WJN, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Goedegebure A. White-matter microstructure and hearing acuity in older adults: a population-based cross-sectional DTI study. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;61:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee YJ, Bae SJ, Lee SH, Lee JJ, Lee KY, Kim MN, Chang Y. Evaluation of white matter structures in patients with tinnitus using diffusion tensor imaging. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(6):515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aldhafeeri FM, Mackenzie I, Kay T, Alghamdi J, Sluming V. Neuroanatomical correlates of tinnitus revealed by cortical thickness analysis and diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroradiology. 2012;54:883–892. doi: 10.1007/s00234-012-1044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan RA, Sutton BP, Tai Y, Schmidt SA, Shahsavarani S, Husain FT. A large-scale diffusion imaging study of tinnitus and hearing loss. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23395. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02908-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Q, Wang Z, Lv H, Zhao P, Yang Z, Gong S, Wang Z. Reorganization of brain white matter in persistent idiopathic tinnitus patients without hearing loss: evidence from baseline data. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:591. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gunbey HP, Gunbey E, Aslan K, Bulut T, Unal A, Incesu L. Limbic-auditory interactions of tinnitus: an evaluation using diffusion tensor imaging. Clin Neuroradiol. 2017;27:221–230. doi: 10.1007/s00062-015-0473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crippa A, Lanting CP, van Dijk P, Roerdink JB. A diffusion tensor imaging study on the auditory system and tinnitus. Open Neuroimag J. 2010;4:16–25. doi: 10.2174/1874440001004010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seydell-Greenwald A, Raven EP, Leaver AM, Turesky TK, Rauschecker JP. Diffusion imaging of auditory and auditory-limbic connectivity in tinnitus: preliminary evidence and methodological challenges. Neural Plast. 2014;2014:145943. doi: 10.1155/2014/145943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benson RR, Gattu R, Cacace AT. Left hemisphere fractional anisotropy increase in noise-induced tinnitus: a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study of white matter tracts in the brain. Hear Res. 2014;309:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryu CW, Park MS, Byun JY, Jahng GH, Park S. White matter integrity associated with clinical symptoms in tinnitus patients: a tract-based spatial statistics study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:2223–2232. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt SA, Zimmerman B, Medina ROB, Carpenter-Thompson JR, Husain FT. Changes in gray and white matter in subgroups within the tinnitus population. Brain Res. 2018;1679:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koops EA, Haykal S, van Dijk P. Macrostructural changes of the acoustic radiation in humans with hearing loss and tinnitus revealed with fixel-based analysis. J Neurosci. 2021;41(18):3958–3965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2996-20.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacobson GP, McCaslin DL. A reexamination of the long latency N1 response in patients with tinnitus. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14(07):393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Melcher JR. Human brain imaging of tinnitus. In: Eggermont J, Zeng FG, Popper A, Fay R, editors. Tinnitus. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piarulli A, Vanneste S, Nemirovsky IE, Kandeepan S, Maudoux A, Gemignani A, De Ridder D, Soddu A. Tinnitus and distress: an electroencephalography classification study. Brain Commun. 2023;5(1):fcad018. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcad018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adjamian P. The application of electro-and magneto-encephalography in tinnitus research–methods and interpretations. Front Neurol. 2014;5:228. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mirz F. Cortical networks subserving the perception of tinnitus-a PET study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120(543):241–243. doi: 10.1080/000164800454503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mirz F, Gjedde A, Sdkilde-Jrgensen H, Pedersen CB. Functional brain imaging of tinnitus-like perception induced by aversive auditory stimuli. NeuroReport. 2000;11(3):633–637. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carpenter-Thompson JR, Akrofi K, Schmidt SA, Dolcos F, Husain FT. Alterations of the emotional processing system may underlie preserved rapid reaction time in tinnitus. Brain Res. 2014;1567:28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bradley MM, Lang PJ. The International Affective Digitized Sounds (IADS-2): Affective ratings of sounds and instruction manual. Tech Rep B-3. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khan RA, Husain FT. Tinnitus and cognition: can load theory help us refine our understanding? Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1197–1204. doi: 10.1002/lio2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmidt SA, Shahsavarani S, Khan RA, Tai Y, Granato EC, Willson CM, et al. An examination of the reliability of seed-to-seed resting state functional connectivity in tinnitus patients. Neuroimage Rep. 2023;3(1):100158. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kok TE, Domingo D, Hassan J, Vuong A, Hordacre B, Clark C, Shekhawat GS. Resting-state networks in tinnitus: a scoping review. Clin Neuroradiol. 2022;32(4):903–922. doi: 10.1007/s00062-022-01170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arnold W, Bartenstein P, Oestreicher E, Römer W, Schwaiger M. Focal metabolic activation in the predominant left auditory cortex in patients suffering from tinnitus: a PET study with [18F] deoxyglucose. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1996;58(4):195–199. doi: 10.1159/000276835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Geven LI, De Kleine E, Willemsen ATM, Van Dijk P. Asymmetry in primary auditory cortex activity in tinnitus patients and controls. Neuroscience. 2014;256:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Langguth B, Eichhammer P, Kreutzer A, Maenner P, Marienhagen J, Kleinjung T, Hajak G. The impact of auditory cortex activity on characterizing and treating patients with chronic tinnitus–first results from a PET study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126(sup556):84–88. doi: 10.1080/03655230600895317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schecklmann M, Landgrebe M, Poeppl TB, Kreuzer P, Männer P, Marienhagen J, Langguth B. Neural correlates of tinnitus duration and distress: a positron emission tomography study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(1):233–240. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zimmerman BJ, Schmidt SA, Khan RA, Tai Y, Shahsavarani S, Husain FT. Decreased resting perfusion in precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex predicts tinnitus severity. Curr Res Neurobiol. 2021;2:100010. doi: 10.1016/j.crneur.2021.100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moring JC, Husain FT, Gray J, Franklin C, Peterson AL, Resick PA, Garrett A, Esquivel PT, Fox PT. Invariant structural and functional brain regions associated with tinnitus: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0276140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fransson P. Spontaneous low-frequency BOLD signal fluctuations: An fMRI investigation of the resting-state default mode of brain function hypothesis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;26(1):15–29. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(34):12569–12574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.De Ridder D, Elgoyhen AB, Romo R, Langguth B. Phantom percepts: tinnitus and pain as persisting aversive memory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(20):8075–8080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018466108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elgoyhen AB, Langguth B, De Ridder D, Vanneste S. Tinnitus: perspectives from human neuroimaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(10):632–642. doi: 10.1038/nrn4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shahsavarani S, Schmidt SA, Khan RA, Tai Y, Husain FT. Salience, emotion, and attention: the neural networks underlying tinnitus distress revealed using music and rest. Brain Res. 2021;1755:147277. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Song JJ, Adhia D. Tinnitus and the triple network model: a perspective. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;15(3):205–212. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2022.00815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Simonetti P, Ono CR, de Godoi Carneiro C, Khan RA, Shahsavarani S, Husain FT, Oiticica J. Evaluating the efficacy of hearing aids for tinnitus therapy–a positron emission tomography study. Brain Res. 2022;1775:147728. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Krick CM, Grapp M, Daneshvar-Talebi J, Reith W, Plinkert PK, Bolay HV. Cortical reorganization in recent-onset tinnitus patients by the Heidelberg Model of Music Therapy. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:49. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krick CM, Argstatter H, Grapp M, Plinkert PK, Reith W. Heidelberg neuro-music therapy enhances task-negative activity in tinnitus patients. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McKenna L, Marks EM, Hallsworth CA, Schaette R. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a treatment for chronic tinnitus: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(6):351–361. doi: 10.1159/000478267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McKenna L, Marks EM, Vogt F. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for chronic tinnitus: evaluation of benefits in a large sample of patients attending a tinnitus clinic. Ear Hear. 2018;39(2):359–366. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Philippot P, Nef F, Clauw L, de Romrée M, Segal Z. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for treating tinnitus. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19(5):411–419. doi: 10.1002/cpp.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roland LT, Lenze EJ, Hardin FM, Kallogjeri D, Nicklaus J, Wineland AM, Piccirillo JF. Effects of mindfulness based stress reduction therapy on subjective bother and neural connectivity in chronic tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(5):919–926. doi: 10.1177/0194599815571556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zimmerman B, Finnegan M, Paul S, Schmidt S, Tai Y, Roth K, Husain FT. Functional brain changes during mindfulness-based cognitive therapy associated with tinnitus severity. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:747. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kleinjung T, Steffens T, Londero A, Langguth B. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for treatment of chronic tinnitus: clinical effects. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:359–551. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Poeppl TB, Langguth B, Lehner A, Frodl T, Rupprecht R, Kreuzer PM, Schecklmann M. Brain stimulation-induced neuroplasticity underlying therapeutic response in phantom sounds. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(1):554–562. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hamza Y, Zeng FG. Tinnitus is associated with improved cognitive performance in non-Hispanic elderly with hearing loss. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:735950. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.735950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ivansic D, Guntinas-Lichius O, Müller B, Volk GF, Schneider G, Dobel C. Impairments of speech comprehension in patients with tinnitus—a review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:224. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]