ABSTRACT

Kamila Hawthorne, chair of the Royal College of General Practioners Council, and Bola Owolabi, director of the National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme, offer a personal perspective on how their professional experiences have led them to see health inequality as urgent priority, and introduce initiatives that can help general practitioners make a difference individually and collectively.

KEYWORDS: health inequality, healthcare inequality, general practice, Core20PLUS5, Deep End, integrated care

Recognising the challenge of health inequalities

A perspective from Kamila Hawthorne, chair of RCGP Council

In 2018, I moved from inner-city Cardiff to Mountain Ash, in the South Wales valleys. Having been a GP for 35 years in suburban Nottingham, inner-city Manchester, and inner-city Cardiff, I was not expecting to be as surprised as I was by the clear demonstration of poverty's effects on health that I found there. Sited in a beautiful Welsh valley, with the Cynon River running along its course, a walk down Mountain Ash's high street shows a line of fast-food outlets, nail and tattoo bars, betting shops and beauty parlours. The Post Office closed last year, there are no banks, greengrocers, bakeries, or butchers' shops. Many of my patients have BMIs well over 35, and the concomitant list of chronic diseases that go with that. Two weeks in, I said to my new partners over coffee: ‘Aren't we missing a trick here? Although we have treatments for these chronic conditions, wouldn't it have been better to have helped patients avoid getting them in the first place?’ They looked at me in horror and said that there was far too much that needed to be done within the surgery walls for time to be spent in schools, community centres, sports centres trying to prevent the development of chronic disease, with outcomes that were uncertain and difficult to measure. Many GPs would agree with that, and certainly our current workload does not leave much headspace for anything more than the patient in front of us (the latest statistics from 23 June show that workload in England alone has grown by 24.5% since 2019, while the GP workforce has reduced by 977 full time equivalent (FTE) GPs over the same period of time1,2).

So, is that correct? Should we be keeping our noses to the appointment grindstone, day after day, mopping up the problems created by unhealthy lifestyles and adverse childhood events? In South Wales, our health legacy includes (as well as Aneurin Bevan, the father of the NHS) the amazing Dr Julian Tudor-Hart. Julian was a GP who spent his life serving a small Welsh Valleys town and conducting seminal research with that community on blood pressure management, salt and dietary intake, among other trials. In 1971, he coined the famous and widely quoted ‘Inverse care law’3 – that those who need care the most are the ones least likely to get it. 50 years later, we see that happening today, across the globe, but also in our own practices. Julian also said that ‘medicine without social justice, is not medicine at all’ – would we agree? And he said that research was important – not only to help us decide what the best treatments and management plans were, but also because that data brought power with it. Power to demonstrate to those who make the funding and planning decisions what effect their decisions will have on the lives of the communities that make up the UK.

Why should we worry about the health inequalities gap? In addition to knowing that poorer communities and vulnerable groups have a shorter lifespan4 and more chronic illness,5 we also know that those countries where the gap between rich and poor is wider have worse outcomes in eleven different health and social problems, including physical and mental health, drug abuse, education, imprisonment, obesity, trust and community life, teenage pregnancies and child wellbeing.6 And this affects both rich and poor in these countries. In the UK, the health inequalities gap has been widening since the publication of the Black Report in August 1980,7 so we should be worrying about what is happening in the UK. And as Sir Michael Marmot says so succinctly in his book ‘The Health Gap’,8 ‘What is the sense of sending people back to the same conditions that made them sick in the first place?’

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, it cast a harsh light on the health and wider inequalities that persist in our communities. The virus and efforts to mitigate its impact had a disproportionate effect on certain sections of the population, including ethnic minority communities, the most socio-economically deprived communities, people with learning disabilities, those with severe mental illness and inclusion health groups.

Even before the pandemic, the issue of health inequality had already been identified as major issue to be addressed across the NHS and the Long-Term Plan9 made tackling health inequalities a clear national priority. Black women in the UK are four times more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth,10 the healthy life expectancy gap between the most and least deprived communities of England is 19 years4 and the disparity between average age at death in people with learning disability and the general population is 22 years for males and 26 years for females.11 Given this context, our health inequalities work does not stop with the COVID-19 response.

While GPs can't individually influence the social and economic factors that result in the health inequalities, there is plenty we can be doing in our own surgeries and practice areas. GPs in Scotland banded together in 2009 to form the ‘Deep End’ movement – covering the 100 practices that served the most deprived communities. Deep End GPs work together to advocate on behalf of their patients across a wide range of issues, using a swimming pool analogy as its title. Since then, the movement has grown across the UK and internationally, with 14 Deep End groups across seven countries. Developing that supportive network has proved valuable to individual practices who are otherwise struggling with their workload and complexity of patients they are seeing.

And we don't have to do it all ourselves! As we explain below, there is much that can be done across professional boundaries and in integrated care systems.

A perspective from Bola Owolabi, director of the National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme

Kamila's experience mirrors mine as a GP working in one of the ex-mining villages in Northeast Derbyshire. I see first-hand how socio-economic deprivation drives the incidence, prevalence and impact of long-term conditions (LTCs) and how other risk factors that cause and exacerbate some of these LTCs, such as smoking rates, have remained stubbornly persistent in poorer areas despite significant declines more generally.12

When I started in my role as director for the National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme in NHS England just over 2 years ago, I made it my mission to speak extensively with people and organisations across the country to gain insights into why, despite decades of publications on health inequalities, measurable progress remained elusive. I was struck by the refrain ‘Don't boil the ocean’. In essence, there was a general view that in an effort to tackle all the causes and manifestations of health inequalities at the same time, energy and resources were being distributed too thinly to be able to make demonstrable impact on any dimension. I surmised from these discussions that we needed focus. Focus, in service of gaining traction and making demonstrable impact within a reasonable time frame. My mantra therefore became – focus, traction, impact.

With wider conversations with fellow GPs and many other groups, and further reflection, I began to see the real value of distinguishing between ‘health inequalities’ and ‘healthcare inequalities’. The former are unfair and avoidable differences in health across the population, and between different groups within society. These include how long people are likely to live, the health conditions they may experience and the care that is available to them. The conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age can impact our health and wellbeing. These are sometimes referred to as wider determinants of health.13 Healthcare inequalities by contrast are indicated by unequal rates of access to healthcare services (relative to need), and inequalities in the experience and outcomes that different social groups obtain from those services. Action to address these inequalities falls squarely under the NHS's control.14

This distinction is a powerful enabler for us as GPs. It liberates us from the paralysis that arises from a feeling of helplessness in effecting improvements to the wider determinants of health (including housing, education, employment, and household income). A focus on healthcare inequalities means we can work within our sphere of influence – healthcare access, experience, and outcomes. We can lean into our role as clinical and professional leaders focusing on quality improvement as a tool with a real emphasis on data for improvement, strengths-based approaches and co-production with communities, patients, and service users.

Addressing the challenge of health inequalities in general practice

Core20PLUS5

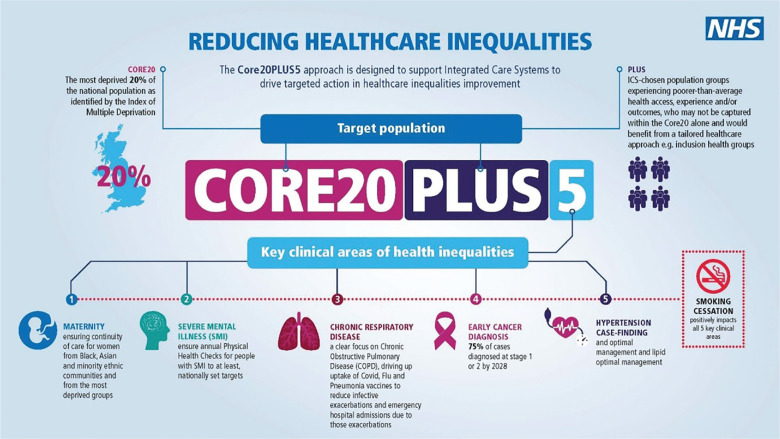

The Core20PLUS5 approach (Fig 1, Fig 2) was developed to help frame and streamline our actions in tackling healthcare inequalities. As an approach, it does not purport to be a silver-bullet solution to the enduring challenge of health inequalities. To use a mechanical analogy, I often describe Core20PLUS5 as a chassis: a structural framework which supports our efforts in taking specific and targeted action to narrow the healthcare inequalities gap.

Fig 1.

Core20PLUS5 approach for adults.

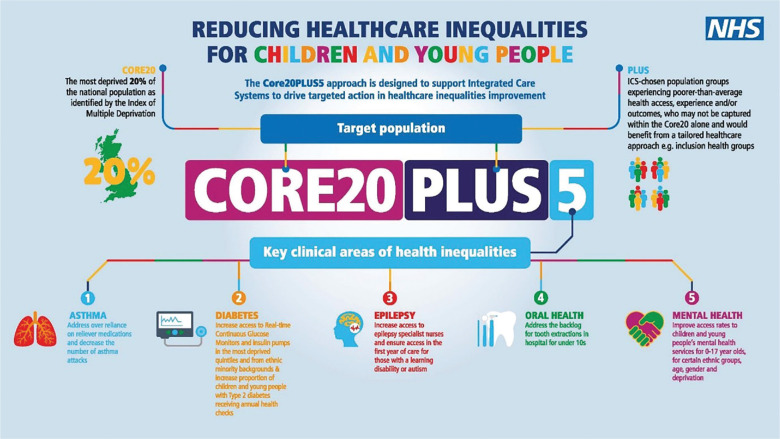

Fig 2.

Core20PLUS5 approach for children and young people.

Core20PLUS5 offers each integrated care system (ICS) in England (including the primary care networks within them) a focused approach to enable prioritisation of energies and resources as they address health inequalities. We present this approach as the NHS contribution to a wider system effort by local authorities, communities and the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector to tackling healthcare inequalities – and it aims to complement and enhance existing work in this area.

It defines a target population cohort – the ‘Core20PLUS’ – and identifies ‘5’ focus clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement. There is an adult version as well as one for children and young people.

Core20PLUS5 (adults)

The approach has three components (Fig 1).

Core20: The most deprived 20% of the national population as identified by the national Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). The IMD has seven domains with indicators accounting for a wide range of social determinants of health.

PLUS: ICS-determined population groups experiencing poorer than average health access, experience, or outcomes, but not captured in the ‘Core20’ alone. This should be based on ICS population health data and will typically include ethnic minority communities, other groups that share protected characteristic groups, coastal communities, people with multiple health conditions, inclusion health groups such as people experiencing homelessness, drug and alcohol dependence, vulnerable migrants, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, sex workers, people in contact with the justice system, victims of modern slavery and other socially excluded groups.

5: The final part sets out five clinical areas of focus, with smoking cessation as a cross cutting theme given the strong social gradient associated with smoking prevalence and the impact of smoking on the severity and impact of the 5 other clinical areas defined. These clinical areas and the specific interventions related to them are:

Maternity: ensuring continuity of care for 75% of women from BAME communities and from the most deprived groups.

Severe mental illness (SMI): ensuring annual health checks for people living with serious mental illness (SMI), bringing SMI in line with the success seen in learning disabilities.

Chronic respiratory disease: a clear focus on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) driving up uptake of covid, flu and pneumonia vaccines to reduce infective exacerbations and emergency hospital admissions due to those exacerbations.

Early cancer diagnosis: driving towards 75% of cases diagnosed at stage 1 or 2 by 2028.

Hypertension case-finding, optimal management and lipid optimal management: to minimise the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke

Core20PLUS5 for children and young people (Core20PLUS5CYP)

The approach for children and young people has a similar structure, again with three components (Fig 2).

Core20: the most deprived 20% of the national population as identified by the national Index of multiple deprivation (IMD). The IMD has seven domains with indicators accounting for a wide range of social determinants of health.

PLUS: the PLUS population groups includes children and young people from ethnic minority communities, coastal communities, inclusion health groups and protected characteristic groups and children and young people with learning disabilities, autism and multiple health conditions, amongst others. Specific consideration should be taken for the inclusion of young carers, looked after children/care leavers and those in contact with the justice system.

5: the final part sets out five clinical areas of focus. The five areas of focus are part of wider actions for ISCs and integrated care partnerships to achieve system change and improve care for children and young people. Governance for these five focus areas sits with national programmes; national and regional teams coordinate local systems to achieve aims.

Asthma: address over-reliance on reliever medications and decrease the number of asthma attacks.

Diabetes: increase access to real-time continuous glucose monitors and insulin pumps across the most deprived quintiles and children and young people from ethnic minority backgrounds; and increase proportion of those with Type 2 diabetes receiving recommended NICE care processes.

Epilepsy: increase access to epilepsy specialist nurses and ensure access in the first year of care for those with a learning disability or autism.

Oral health: reduce tooth extractions due to decay for children admitted as inpatients in hospital aged 10 years and under.

Mental health: improve access rates to children and young people's mental health services for 0–17-year-olds, for certain groups related to ethnicity, age, gender and deprivation.

The hope is that, by differentially focusing our efforts and energies on those experiencing the most disadvantage and those clinical areas making the most contribution to both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy gaps between the rich and poor and across other domains of disadvantage, we can gain some traction and demonstrate measurable impact within a reasonable timeframe. Our communities are justifiably impatient to see this happen.

Beyond the scope of healthcare inequalities, we can be influential members within the ICS and make meaningful contributions to materially improve the lot of our patients and communities through closer links with colleagues in local authorities, the VCSE sector, and faith and other community outreach organisations. This is where our social prescriber link workers and other roles coming under the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme can play a bridging role between general practice and those responsible for the wider determinants, such as housing liaison officers. In doing so, we will be expanding our sphere of influence beyond healthcare inequalities and reducing our sphere of concern in relation to the social determinants.

Health inequality as a strategic priority for the Royal College of General Practitioners

There is more that we can all do collectively. As chair of the RCGP, I [KH] have had the privilege of selecting four strategic priorities for my 3-year term of office.15 With my working background, you won't be surprised to know that one of these is indeed health inequalities. We are a large membership body with over 54,000 members and there is much happening across the UK that we need to share so that we are not all re-inventing the wheel. I've designed our RCGP approach in three tiers:

What we can all be doing in our individual practices – we will collect examples of good practice and design a toolkit to help practices work out what they feel able to do in their own contexts. Practices vary hugely across the UK in terms of their list sizes, types of communities they serve, and urbanisation/rurality. Each must find its own level to work in comfortably. All information will be posted on our Health Inequalities Hub online, free to access by anyone.

What we can be doing in groups of practices, working across teams in both health and social care, with third sector organisations, local councils and local community groups. Again, there are many examples of innovative and exciting work that is proving successful on a locality level and again, the RCGP will be showcasing as many as we can find.

What we should be doing at a national level, in our daily work with other national bodies (such as the Kings Fund, Nuffield Trust, Health Foundation etc), the other royal medical colleges, academics with special interest in health inequalities, and the NHS. This includes gathering best evidence and best practice and using the data (as advocated by Julian Tudor Hart) to lobby government and political parties to influence their thinking and planning for the years ahead. This is especially important and urgent as we come up to a general election in 2024.

As GPs, it is surprising how often you might find yourself in the local or even national spotlight, and able to put your lived experience of health inequalities and its human effects on people to a wide audience. So be prepared! Think about what you might want to say, as your patients' advocates, if you get the chance. If you have experience of working on health inequalities in your communities, be prepared to speak up about the work, to reach the widest possible audience. Together we are much stronger than when we are working alone.

References

- 1.NHS Digital . Appointments in general practice. NHS Digital, 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/appointments-in-general-practice [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS Digital . General Practice Workforce. NHS Digital, 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;297:405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office for National Statistics . Health state life expectancies by national deprivation deciles, England and Wales: 2018 to 2020. ONS, 2022. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthinequalities/bullet.ins/healthstatelifeexpectanciesbyindexofmultipledeprivationimd/2018to2020 [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinson A. Living in poverty was bad for your health long before Covid 19. Health Foundation, 2020. www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/living-in-poverty-was-bad-for-your-health-long-before-COVID-19 [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The spirit level: why more equal societies almost always do better. Bloomsbury Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black D. The Black Report: Report of the Working Group on Inequalities in Health. Department of Health and Social Security, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marmot M. The health gap: the challenge of an unequal world. Bloomsbury Press. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS England . The NHS Long Term Plan. NHSE, 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ [Accessed 20 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.MBRACE UK. Maternal mortality 2019–2021. The National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, 2023. www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/data-brief/maternal-mortality-2019-2021 [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.White A, Sheehan R, Ding J, et al. Learning from lives and deaths – People with a learning disability and autistic people (LeDeR) report for 2021. King's College London, 2022. www.kcl.ac.uk/research/leder [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan J. The Khan review: making smoking obsolete: Independent review into smokefree 2030 policies. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022. www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-khan-review-making-smoking-obsolete [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS England . What are healthcare inequalities? www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/what-are-healthcare-inequalities [Accessed 10 October 2023].

- 14.Gainsbury S, Hutchings R. Review of the Mayor of London's Health Inequalities Test. The Nuffield Trust, 2022. www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/review-of-the-mayor-of-london-s-health-inequalities-test [Accessed 10 October 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of General Practitioners . Strategic plan 2023 to 2026: Building a sustainable future for general practice. Available at www.rcgp.org.uk/about [Accessed 10 October 2023].