Abstract

The germination protease (GPR) of Bacillus megaterium initiates the degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. Trypsin treatment of the 46-kDa GPR zymogen (termed P46) removes an ∼15-kDa C-terminal domain generating a 30-kDa species (P30) which is stable against further digestion. While P30 is not active, it does autoprocess to a smaller form by cleavage of the same bond cleaved in conversion of P46 to the active 41-kDa form of GPR (P41). Trypsin treatment of P41 cleaves the same bond in the C-terminal part of the protein as is cleaved in the P46→P30 conversion. While the ∼29-kDa species generated by trypsin treatment of P41 is active, it is rapidly degraded further by trypsin to small inactive fragments. These results, as well as a thermal melting temperature for P41 which is 13°C lower than that for P46 and the unfolding of P41 at significantly lower concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride than for P46, are further evidence for a difference in tertiary structure between P46 and P41, with P46 presumably having a more compact stable structure. However, circular dichroism spectroscopy revealed no significant difference in the secondary structure content of P46 and P41. The removal of ∼30% of P46 or P41 without significant loss in enzyme activity localized GPR’s catalytic residues to the N-terminal two-thirds of the molecule. This finding, as well as comparison of the amino acid sequences of GPR from three different species, analysis of several site-directed GPR mutants, determination of the metal ion content of purified GPR, and lack of inhibition of P41 by a number of protease inhibitors, suggests that GPR is not a member of a previously described class of protease.

Between 10 and 20% of total spore protein is degraded to amino acids in the first minutes of germination of spores of Bacillus species (30). The proteins degraded are a group of small, acid-soluble proteins (SASP) unique to the spore stage of the life cycle. The α/β-type SASP, which are coded for by a multigene family, are bound to the dormant spore’s DNA and provide a significant component of spore resistance to heat, hydrogen peroxide, and UV radiation (28, 30, 31). The γ-type SASP, which are coded for by a single gene, are also in the spore core (the site of spore DNA) but are not bound to any macromolecule. SASP degradation at the beginning of spore germination both frees up the DNA for transcription and provides amino acids that are used for protein synthesis during subsequent development (22, 30).

SASP degradation during spore germination is initiated by one or two endoproteolytic cleavages catalyzed by a sequence specific germination protease termed GPR which is synthesized during sporulation at about the same time as its SASP substrates (30). GPR is synthesized as a protein of 46 kDa as measured by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE); this species, termed P46, is inactive (13). Two hours later in sporulation, P46 undergoes intramolecular autoprocessing which removes an N-terminal propeptide of 15 (Bacillus megaterium) or 16 (B. subtilis) amino acids; the new, fully active form of GPR is called P41 (13, 24). Both P46 and P41 are tetramers, and only the tetrameric form of P41 is active (12). The autoprocessing of P46 to P41 is triggered both in vivo and in vitro by low pH, dipicolinic acid, and dehydration (8). Although active in vitro, P41 carries out no SASP degradation during sporulation because the conditions inside the developing and dormant spore (in particular the dehydration and mineralization) are not favorable for enzymatic action. However, in the first minutes of spore germination, the spore core rehydrates, allowing rapid attack of GPR on SASP. Synthesis of GPR in an inactive form and its autoprocessing at the correct time in sporulation are essential to generate a fully resistant spore; a strain with a GPR variant that autoprocesses P46 to P41 ∼1 h earlier during sporulation produces spores that are more sensitive than wild-type spores to a variety of treatments, because the α/β-type SASP content of the mutant spores is reduced (6).

In addition to the autoprocessing reaction converting P46 to P41, the P41 of B. megaterium also undergoes an additional autoprocessing to P39 with loss of an additional seven N-terminal residues (8). The enzymatic activities of P39 and P41 are identical, and P39 is not generated from P41 of B. subtilis. Consequently, the generation of P39 with B. megaterium GPR may not have any functional significance.

While the role played by GPR in SASP degradation as well as its autoprocessing are reasonably well understood, little is known of the structural differences between P46 and P41 and the nature of GPR’s active site(s). Indeed, the precise class of protease to which GPR belongs has not been established. To obtain more information on these latter topics, we have analyzed the trypsin digestion products generated from P46 and P41 and have used a variety of techniques in an attempt to determine the class of protease to which GPR belongs. The latter data suggest that GPR is not a member of a previously described class of proteases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and plasmids used and isolation of DNA.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were routinely grown at 37°C in 2× YT medium (5 g of NaCl, 16 g of tryptone, and 10 g of yeast extract per liter). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| JM83 | ||

| UT481 | lacIq | |

| PS2479 | UT481 pPS2479 Ampra | This work |

| PS2524 | UT481 pPS2524 Ampr | This work |

| PS2569 | UT481 pPS2569 Ampr | This work |

| PS2577 | UT481 pPS2577 Ampr | This work |

| PS 2578 | UT481 pPS2578 Ampr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPS740 | pUC12 with B. megaterium wild-type gpr; Ampr | 32 |

| pPS1907 | pTZ19U with B. megaterium gpr from which all propeptide residues are deleted; Ampr | 32 |

| pPS1910 | pUC12 with B. megaterium gpr from which all propeptide residues are deleted; Ampr | 6 |

| pPS2339 | pUC12 with B. megaterium gpr lacking propeptide residues 2 to 4; Ampr | 17 |

| pPS2340 | pUC12 with B. megaterium gpr lacking propeptide residues 2 to 7; Ampr | 17 |

| pPS2341 | pUC12 with B. megaterium gpr lacking propeptide residues 2 to 10; Ampr | 17 |

| pPS2342 | pUC12 with B. megaterium gpr lacking propeptide residues 2 to 13; Ampr | 17 |

| pPS2479 | pPS1910 with B. megaterium gpr with KDALAN instead of KDIALEN in the P41→P39 cleavage site; Ampr | This work |

| pPS2524 | pPS1910 with B. megaterium gpr C115A; Ampr | This work |

| pPS2569 | pPS1910 with B. megaterium gpr S274A S276A; Ampr | This work |

| pPS2577 | pPS1910 with B. megaterium gpr S219A; Ampr | This work |

| pPS2578 | pPS1910 with B. megaterium gpr S229A; Ampr | This work |

Ampr, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) resistant.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

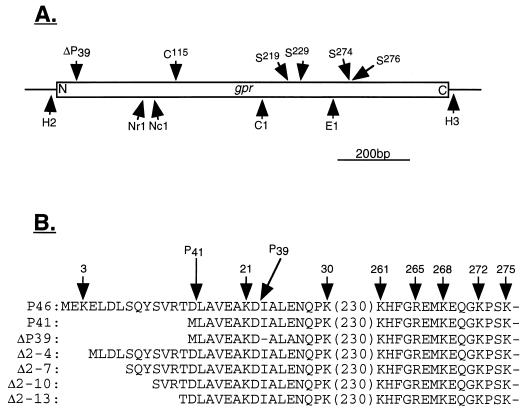

We used the megaprimer-based PCR method (26) to make mutations in B. megaterium gpr in which Ser219 or Ser229 is replaced by Ala (Fig. 1A). The oligonucleotide primers used for the first round of PCR were A (5′-CAAGCTCTAATACGACTCAC-3′), B (5′-CATCCGGGGGCTGGGGTTGGAAAC-3′), and C (5′-GCGTAAAGAAATCGCTATGAAACACTTG GC-3′). Oligonucleotide A is in the T7 promoter of the pTZ19U portion of pPS1907 (Table 1); oligonucleotide B begins at nucleotide (nt) 753 and ends at nt 776 and oligonucleotide C begins at nt 779 and ends at nt 809 of the coding sequence of B. megaterium gpr. Oligonucleotides B and C are complementary to the gpr sequence except for the underlined nucleotides. In the first round of PCR, the reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 100 pmol of primer B or C and 100 pmol of primer A, 1.5 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 ng of template (plasmid pPS1907), and 10 μl of 10× Vent DNA polymerase buffer. Reaction mixtures were overlaid with mineral oil and heated for 8 min at 94°C, 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase was added, and samples were subjected to 35 cycles of PCR (1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C) and incubated for 10 min at 72°C at the end of the last cycle. The synthesized megaprimers were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel to verify that they were of the expected sizes and then used for the second round of PCR. The second round of PCR was carried out in 50 μl containing ∼50 ng of one of the megaprimers, 500 pmol of primer D (5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTG-3′), which is complementary to the sequence of pTZ19U in pPS1907 downstream of the multiple cloning site, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 ng of HindIII-linearized pPS1907 purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and 5 μl of 10× Taq DNA polymerase buffer. Samples were treated as described above, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase was added, and PCR was performed as described above. The final PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis; fragments with the expected sizes were excised and ligated into plasmid pCRII (Invitrogen). The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli INVαF′ cells (Invitrogen), and transformants were selected on 2×YT agar plates containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (40 μg/ml). Plasmids were isolated from white colonies, and digestion with HincII and HindIII identified plasmids with the appropriate ∼1.5-kb insert. DNA sequence analysis confirmed the presence of the desired mutations and that they were the only mutations present in the 211-bp ClaI-EagI fragment of B. megaterium gpr (Fig. 1A). This ClaI-EagI fragment was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and ligated to ClaI-EagI-digested pPS1910 which had been purified to obtain the large fragment. The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli UT481 to ampicillin resistance, and plasmid DNA from several clones was isolated and sequenced to ensure that gpr had acquired the desired mutation. E. coli UT481 strains carrying plasmids with the gpr S219A mutation and the gpr S229A mutation were called PS2577 and PS2578, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Locations of restriction sites in B. megaterium gpr and possible catalytic residues in B. megaterium GPR (A) and amino acid sequences of B. megaterium GPR variants (B). (A) The locations of restriction sites and codons for possible catalytic residues in B. megaterium gpr were taken from reference 30. The locations of codons for possible catalytic residues are given above the gene (open box), and restriction sites (C1, ClaI; E1, EagI; H2, HincII; H3, HindIII; NcI, NcoI; NrI, NruI) are indicated below the gene. N and C denote the N- and C-terminal coding regions, respectively. Note that the HincII and HindIII sites are outside the gpr gene’s coding sequence. The arrow labeled ΔP39 denotes the region in which P41 autoprocesses to P39. (B) Amino acid sequences (in one-letter code) of various forms of GPR. The sequences of P46 and P41 (note that this is P41 overexpressed in E. coli) are from references 6 and 24. The sequence of ΔP39 is from this work, and those of the variants lacking 3 to 12 propeptide residues are from reference 17. The numbers above the sequences are the positions of lysine or arginine residues in P46; arrows labeled P41 and P39 denote the sites of cleavage generating P41 and P39, respectively.

The mutations in B. megaterium GPR in which both Ser274 and Ser276 are replaced by Ala, in which the single Cys is replaced by Ala, and in which the P41→P39 autoprocessing site is modified to prevent P41→P39 conversion (ΔP39) (Fig. 1) were generated with a Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The template used was pPS1907, and the phosphorylated primers were D (5′-GACGGCCAGTGAACGAGCTCGGTAC-3′; the selection primer which abolishes the unique EcoRI site in the multiple cloning site), F (5′-CAGGGAAAGCCGGCTAAGGCTCTGCTTCCGTCC-3′; used to change [underlined residues] Ser274 and Ser276 to Ala), G (5′-GATGATGCTAGCGCACTTGTAGTGGG-3′; used to change [underlined residues] Cys115 to Ala), and H (5′-CGAAGCAAAAGACGCGTTAGCAAATCAGCC-3′; used to change [underlined residues] the sequence coding for KDIALEN in the P41→P39 autoprocessing site to one coding for KDALAN). Given GPR’s sequence specificity, the latter change should eliminate P41→P39 conversion (6, 8). The presence of the desired mutations in the plasmids obtained was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis, and the EagI-HindIII fragment (double mutant), the NruI-ClaI fragment (Cys-to-Ala mutation), and the HincII-NcoI fragment (mutation in the P41→P39 autoprocessing site) were excised and ligated to EagI-HindIII-digested pPS1910, NruI-ClaI-digested pPS1910, and HincII-NcoI-digested pPS1910, respectively (Fig. 1A). The ligation mixtures were used to transform E. coli UT481 to ampicillin resistance, and plasmid DNA from several clones was isolated and sequenced to confirm the presence of the desired mutations. The E. coli UT481 strains carrying plasmids generated with gpr S274A S276A, gpr C115A, and ΔP39 (lacking the P41→P39 cleavage site) were named PS2569, PS2524, and PS2479, respectively.

Protein overexpression and purification.

B. megaterium P46, P41, and the GPR variants lacking 3, 6, 9, or 12 propeptide residues were purified, respectively, from E. coli JM83 carrying plasmid pPS740, pPS1910, pPS2339, pPS2340, or pPS2341 and from E. coli UT481 with plasmid pPS2342 as described previously (6, 17). All other strains for overexpression of GPR were grown at 37°C in 2×YT medium plus ampicillin (50 μg/ml). At an optical density at 600 nm of 0.9, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to 1 mM, and the cells were harvested after 2 h of further growth at 37°C. GPR was routinely purified from these cells as described (6, 17).

The procedure used to purify GPR for analysis of metal ions was a modified version of the published procedure that gives a higher yield and better purity. Cells from 2 liters of culture of either PS2479 or E. coli JM83 carrying pPS740 obtained as described above were broken by sonication in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM CaCl2, 20% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol), the mixture was centrifuged, and nucleic acids were precipitated from the supernatant fluid with streptomycin sulfate (20 mg/ml) essentially as described elsewhere (24). After centrifugation, the proteins in the supernatant fluid were precipitated with 60% ammonium sulfate, resuspended in buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM CaCl2, 20% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl), and dialyzed overnight at 10°C against 2 liters of buffer B. The protein was loaded on a DEAE-Sephadex A-50 column (5 by 15 cm) equilibrated with buffer B and eluted with a 1-liter linear gradient from 100 to 500 mM NaCl in buffer B. The fractions containing GPR were pooled, precipitated with 70% ammonium sulfate, dissolved in 10 ml of buffer B, and dialyzed overnight against 1 liter of the same buffer. The protein was then loaded on a 12-ml anion-exchange column (UNO Q-12 column; Bio-Rad) on a BioLogic FPLC system (Bio-Rad) and eluted as described above but with a total gradient volume of 180 ml. The fractions containing GPR were pooled, precipitated with 70% ammonium sulfate, dissolved in 10 ml of buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM CaCl2, 20% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl), and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer. The dialyzed protein (5 to 10 ml) was finally run through a 340-ml Sephacryl S-200 26/60 gel filtration column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer C. The fractions containing GPR were pooled, precipitated with 70% ammonium sulfate, resuspended, and dialyzed overnight against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–20% glycerol. The protein was concentrated in Centricon-30 concentrators (Amicon) to ∼20 mg/ml and stored at −20°C.

Limited proteolytic digestion.

GPR (0.5 to 1 mg/ml) was incubated at 37°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–20% glycerol–5 mM CaCl2 with tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Worthington) at a GPR/trypsin ratio of 1,000:1 (wt/wt). The inclusion of glycerol in the digestion buffer was essential to obtain stable functional products, as in the absence of glycerol, both P46 and P41 were rapidly degraded to small fragments. Reactions were stopped by addition of 2× electrophoresis sample buffer and boiling for 5 min, and aliquots were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 15% gel. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and stained with Coomassie blue; protein bands were analyzed by automated amino acid sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) as described elsewhere (11, 17).

GPR assay and autoprocessing.

GPR was assayed as described previously (12). When trypsin-digested P46 or P41 was assayed, soybean trypsin inhibitor was added to digests in a 2:1 molar ratio with trypsin prior to GPR assays. When crude extracts were to be assayed, GPR was overexpressed as described above and the cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cells from ∼50 ml of culture were resuspended in 2 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–20% glycerol, disrupted by sonication, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The protein concentration of the supernatant fluid was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (14).

The autoprocessing of the stable trypsin digestion product of P46 (termed P30) was for 3 h at 37°C with 50 μg of protein in 100 μl of 250 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (pH 6.2)–10 mM dipicolinic acid–20 mM CaCl2–40% polyethylene glycol 8000 (molecular grade; Sigma) as described previously (17). To ensure complete inactivation of trypsin in P30, a twofold excess of soybean trypsin inhibitor over trypsin was added prior to initiation of autoprocessing.

Effect of protease inhibitors on GPR activity.

Two different procedures were used to test the effects of protease inhibitors on the activity of purified P41. To test the effect of 1,10-orthophenanthroline (Ophen), P41 (0.2 mg/ml) was dialyzed overnight at 10°C against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–20% glycerol–2 mM Ophen prior to enzyme assays (1). To test the effects of 250 μM N-acetylimidazole (NAI), 1 mM 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin (DCI), 10 mM disopropylfluorophosphate (DFP), 10 mM 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid (HQSA), 1 mM iodoacetic acid (IAA), 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 10 μM pepstatin, and 3 or 10 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), the inhibitors were routinely incubated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–20% glycerol with 20 to 200 μg of purified P41 per ml. Incubation was for 4 h at 23°C for NAI (the buffer used was 25 mM MOPS [pH 7.4]), 2 h at 4°C for DCI (with no glycerol in the incubation), 45 min at 37°C for DFP [50 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (pH 10) was used with this inhibitor in addition to Tris-HCl], 30 min at 37°C for HQSA, 1 h at 23°C for IAA, overnight at 23°C for NEM, 1 h at 23°C for pepstatin (with 20 μg of P41 per ml), and 45 min at 23°C for PMSF. Aliquots of the incubation mixtures were assayed for GPR activity as described above both before and after incubation, and in parallel with P41 samples incubated similarly but without inhibitors. In some cases the discontinuous colorimetric assay for GPR (12, 29) was used, as some inhibitors inhibit the aminopeptidase used in the GPR assay.

Metal analysis.

GPR for metal analysis was purified and concentrated as described above and then dialyzed exhaustively against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–10% glycerol–1 mM CaCl2 in otherwise metal-free water (Milli-Q); this dialysis buffer had <2 μM Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+, or Fe2+. Standard solutions were made with the dialysis buffer as the diluent, and metal analyses were carried out on a Leeman PS 1000 ICP atomic absorption spectrometer. The instrument was calibrated, and standards were checked to verify the calibration.

CD spectroscopy, thermal melting, and guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) denaturation.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded with an AVIV 62DS spectropolarimeter interfaced to a personal computer. Spectra were collected at 20°C for solutions containing 1.9 mg of P41 or 1.6 mg of P46 per ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–10% glycerol–2 mM EDTA. The glycerol and CaCl2 were present to ensure protein stability. The CD spectra were measured every 0.5 nm with 2-s averaging per point and a 2-nm bandwidth; a 0.01-cm-path-length cell was used. Spectra were signal averaged by adding five scans, and the baseline was corrected by subtracting a spectrum for the buffer obtained under identical conditions. The temperature was maintained by a Lauda RS2 circulating water bath, and the cell temperature was measured with a thermosensor. The protein concentration in this experiment was determined from the UV absorption at 280 nm, using calculated molar absorption coefficients of 5,960 mol−1 cm−1 for P41 and 7,450 mol−1 cm−1 for P46 (14).

For CD analysis of thermal melting, proteins were at 0.2 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–20% glycerol. Measurements were at 220 nm, using a 3-nm bandwidth and a 1-cm cell. Data points were determined every 0.5°C, and the measured signal was averaged 10 s per point. The temperature of the cell holder was controlled and monitored as described above, and the temperature of the sample inside the cell was measured with a Bailey Instruments Bat 8 digital thermometer with a Sensotreck thermistor. The CD data at each temperature were converted to ellipticity in millidegrees, and the data were fit to thermodynamic models by a standard strategy (10). The melting temperature of each protein was defined as the midpoint of the thermal unfolding process.

For measurement of unfolding by GuHCl, the ellipticity at 220 nm was measured at 20°C essentially as described above. P46 or P41 (5 mg/ml) was diluted 1/100 in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM CaCl2–20% glycerol containing various concentrations of GuHCl (ultrapure; ICN). The ellipticity was measured after both 15 min and 2 h of incubation to ensure that the unfolding process was complete.

RESULTS

Proteolytic digestion of GPR.

Previous work has indicated that the only covalent change in conversion of P46 to P41 is removal of 15 (B. megaterium) or 16 (B. subtilis) amino-terminal residues (24). To further probe the structures of both P46 and P41, we digested these proteins with trypsin and analyzed both the sequences and the activities of the digestion products. Trypsin rapidly converted P46 to a 30-kDa species (termed P30) (Fig. 2) that exhibited no further degradation after 24 h (data not shown). The amino-terminal sequence of P30 was ELDLS, and its molecular mass measured by MALDI-TOF was 28,798.1 Da. These data indicate that P30 is generated by trypsin cleavage after K3 and K268 (Fig. 1A), giving a polypeptide with a calculated mass of 28,756.9 Da, in good agreement with the value determined experimentally.

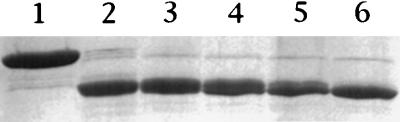

FIG. 2.

Digestion of P46 with trypsin. Purified P46 was incubated with trypsin as described in Materials and Methods. At various times, aliquots (∼10 μg of protein) were withdrawn and subjected to SDS-PAGE (15% gel), and the proteins were stained with Coomassie blue. The GPR samples run in lanes 1 to 6 were digested for 0, 2, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively. Molecular weight markers run in parallel (not shown) indicated that the major band in lane 6 is ∼30 kDa, and this band was analyzed for both molecular weight and N-terminal amino acid sequence.

Given the stability of P30, it was of obvious interest to compare some of its properties to those of P46. Analysis by gel filtration indicated that P30 is tetrameric (data not shown), as is P46 (12). In common with P46, P30 could autoprocess to a slightly smaller form when incubated under the conditions previously shown to promote P46→P41 conversion (Fig. 3). This smaller form was tetrameric (data not shown), and its N-terminal sequence (Fig. 3, band b) was LAVEA, which is that expected for cleavage of P30 at the site of P46→P41 conversion (6, 24). However, we could not detect GPR activity in the processed P30 presumably because of the instability of the active form of P30 (see below) and the conditions used for autoprocessing (pH 6.2 and no glycerol).

FIG. 3.

Autoprocessing of the stable P30 domain of trypsin-digested P46. P30 was generated and incubated under autoprocessing conditions as described in Materials and Methods; an aliquot (10 μg) was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid, resuspended in SDS sample buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE (12% gel). Lane 1, unprocessed P30; lane 2, autoprocessed P30. Arrows a and b denote the migration positions of P30 and the autoprocessed product, respectively.

In addition to gaining enzymatic activity, another change occurring upon conversion of P46 to P41 is an increase in the reactivity of the protein’s single sulfhydryl group with 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) (7). However, the sulfhydryl group in P30 was less reactive than that of P41 and exhibited a reactivity similar to that in P46 (data not shown). This is further evidence that the increased reactivity of the sulfhydryl group in P41 is caused only by the loss of the propeptide, as was suggested by previous work (7, 17), and further, that loss of the C terminus of P46 does not unfold the protein. If the latter was the case, we would most likely have seen an increase in the reactivity of the sulfhydryl group in P30, as is observed in P41 (7).

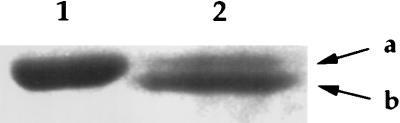

The results of trypsin digestion of P41 were quite different from those with P46, as P41 was much less resistant to trypsin and was degraded to fragments of less than 10 kDa in ∼30 min; however, short-lived active intermediates of ∼27 and ∼29 kDa were generated (Fig. 4). Analysis of the N-terminal sequences of these two species gave MLAVE for the larger intermediate and DALAN for the smaller one (note that this experiment used ΔP39). While the first sequence is of intact P41, the second is generated by cleavage after K21 (Fig. 1B). The molecular masses of the two species as determined by MALDI-TOF were 27,302.9 and 26,760.8 Da, respectively, in fairly good agreement with the molecular masses calculated (27,309.4 and 26,566.4 Da), assuming that a second tryptic cleavage takes place after K268 as in generation of P30 from P46. While these two fragments were active (Fig. 4), their activity was lost within at most a few hours, even if samples were frozen (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Digestion of P41 with trypsin. Purified P41 was incubated with trypsin as described in Materials and Methods, and at various times aliquots (10 μg of protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (15% gel). The numbers below the lanes give the percentages of the initial activity of the enzyme assayed as described in Materials and Methods; the value for undigested P41 was set at 100%. The GPR samples in lanes 1 to 6 run were digested for 0, 2, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively. The two bands in lane 4 were taken for analysis of molecular weight and N-terminal protein sequence. Molecular weight markers run in parallel (not shown) indicated that the latter two bands ran at 29 and 27 kDa.

In previous studies, we showed that deletion of up to nine residues of the B. megaterium GPR propeptide did not result in a protein with significant activity, while deletion of 12 of the propeptide residues gave a protein with 30% of the activity of P41 (17). Digestion of GPR variants lacking three or six propeptide residues with trypsin gave essentially the same result as did digestion of P46; i.e., a stable inactive species of ∼30 kDa was generated (data not shown). In contrast, digestion of the variants lacking 9 and 12 propeptide residues with trypsin gave results similar to those with P41, i.e., rapid digestion of the proteins with generation of short-lived active intermediates (data not shown).

Analysis of P46 and P41 structures.

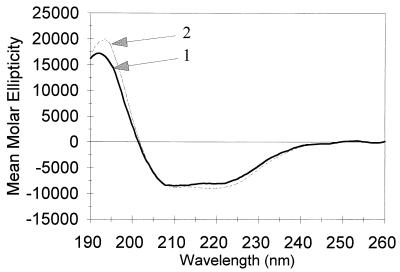

The differences in sulfhydryl reactivity and trypsin sensitivity of P46 and P41 (7) indicate that these proteins differ somewhat in structure; this variance could reflect a difference in secondary structure, in tertiary structure, or in both. We used CD spectroscopy to assess the secondary structure content of P41 and P46. The two proteins had very similar far-UV CD spectra, including characteristics found in proteins with α helices (Fig. 5). Analysis of the spectra between 190 and 260 nm by the method of Chang et al. (3) indicated that P41 contained 21% ± 5% α-helix structure, 58% ± 5% β sheet, and 21% ± 5% random coil; for P46, the corresponding values were 19% ± 5%, 51% ± 5%, and 28% ± 5%.

FIG. 5.

CD spectra of P41 and P46. The far-UV spectra of P41 (1.9 mg/ml) and P46 (1.6 mg/ml) were recorded and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows 1 and 2 denote the spectra of P46 and P41, respectively.

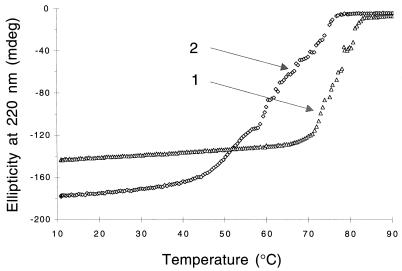

Although the CD spectroscopy would not have detected small differences in secondary structure between P46 and P41, the foregoing data indicate that these proteins have very similar secondary structures. This finding further suggests that the differences in trypsin sensitivity and sulfhydryl group reactivity of P41 and P46 are due to difference in the tertiary structures of these two proteins. To study this point further, we measured the thermal melting of P41 and P46 as described in Materials and Methods and found that P41 was significantly less stable than P46, their melting temperatures being 63 and 76°C, respectively (Fig. 6). The profile of the thermal unfolding of P41, as seen by CD analysis, was quite different and more irregular than that of P46, and P41 unfolding was initiated at a significantly lower temperature. Using another method to compare the stabilities of P46 and P41, we calculated that the GuHCl concentrations needed for 50% unfolding of P41 and P46 (determined as described in Materials and Methods) were 1.4 M for P41 and 2 M for P46 (data not shown). These additional experiments further indicate that P46 has a significantly more stable, and presumably more compact, structure than P41.

FIG. 6.

Thermal unfolding of P46 and P41. The thermal unfolding of P46 and P41 was determined by analysis of CD at 220 nm as described in Materials and Methods. Curves 1 and 2 denote the melting points of P46 and P41, respectively.

Analysis of GPR residues essential for catalysis.

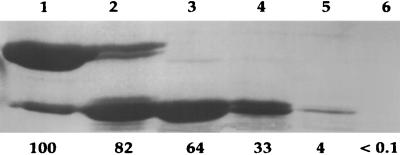

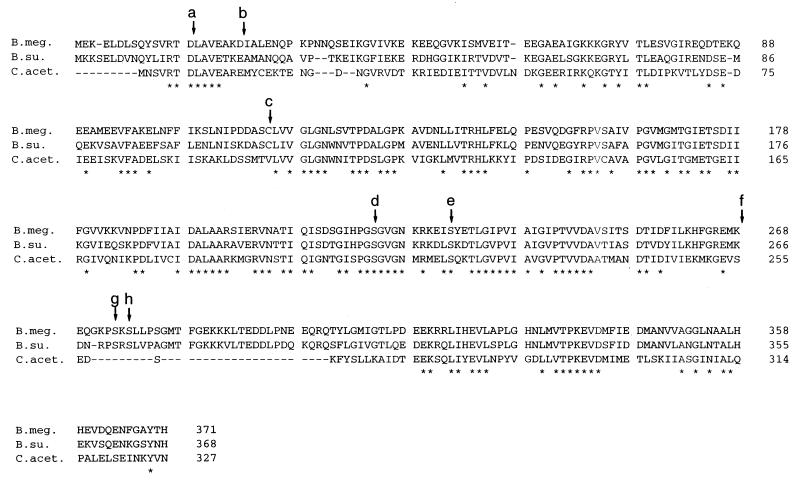

The removal of ∼30% of GPR residues without loss of enzyme activity or the capacity for autoprocessing indicates that the residues essential for GPR catalysis must reside in the remaining 70% of the protein. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of GPR from B. megaterium and B. subtilis has previously failed to reveal any consensus sequence for any known class of protease (32). This analysis can now be extended further (Fig. 7), as the sequence of GPR from Clostridium acetobutylicium has recently become available from Genome Therapeutics Corporation (Waltham, Mass.) through the Internet at www.cric.com. Analysis of these three protein sequences shows that the sequence in the P46→P41 cleavage site is the same in all three proteins, but the clostridial protein has a much shorter propeptide. Again, there are no conserved signature consensus sequences for aspartic or cysteine proteases, metalloproteases, or serine proteases, the four main classes of proteases (2, 19–21). However, comparison of these three sequences does give information on residues that may or may not play a role in catalysis. Thus, the single cysteine residue conserved in the GPR of the two Bacillus species is replaced by a valine in the clostridial enzyme, although the latter protein contains a cysteine residue at position 147. There are also two serines that are conserved in the three GPRs; these residues are Ser219 and Ser229 in B. megaterium GPR. Ser274 and Ser276 of B. megaterium GPR are also conserved in B. subtilis GPR but not in the C. acetobutylicum protein. While the latter enzyme has Ser258 in the same region which might substitute for either Ser274 or Ser276, these more carboxyl-terminal serines seem unlikely to be essential for catalysis, as they are probably removed by the trypsin digestion, generating P30 and the analogous active forms generated from P41.

FIG. 7.

Amino acid sequence alignment of GPRs from various species. The protein sequences were aligned by using the ClustalW program. Gaps introduced into the sequences are indicated by dashes. Positions at which identical residues are present in proteins from all three species are indicated by asterisks below the sequence. Numbers at the right indicate the last residue in that row for each protein. The labeled arrows denote the site cleaved in the generation of P41 (a), the site cleaved in generation of P39 (b), the single cysteine in GPR from Bacillus species (c), two serine residues conserved in all three proteins (d and e), the likely site of trypsin cleavage generating P30 from P46 (f), and serine residues conserved in the Bacillus proteins (g and h). Sources of the sequences: Bacillus megaterium (B. meg) (32), Bacillus subtilis (B. su) (32), and Clostridium acetobutilycum (C. acet) (the Internet at www.cric.com).

Previous work suggested that GPR might indeed be a serine protease, as the enzyme’s activity was inhibited by PMSF (29). We have confirmed this finding for purified P41, as the enzyme was inhibited completely by incubation as described in Materials and Methods with 10 mM PMSF and ∼60% by incubation with 3 mM PMSF (data not shown). However, P41 was not inhibited by treatment with DCI or DFP as described in Materials and Methods (the latter inhibitor at both pH 7.4 and 10), conversion of P41 to P39 was not inhibited by 10 mM PMSF, and incubation of P46 overnight with 10 mM PMSF did not inhibit significant autoprocessing of P46 to P41 (data not shown). These findings call into question the identification of GPR as a serine protease. The enzyme was also not inhibited by treatment with pepstatin, IAA, and NEM as described in Materials and Methods, suggesting that GPR is neither an aspartic nor a cysteine protease, nor was it inhibited by NAI (data not shown).

To definitively establish or rule out a role for various residues in GPR catalysis, we made a number of site-directed mutants of B. megaterium P41. All of these GPR variants were overexpressed to very similar high levels in E. coli (data not shown), and assay of their enzymatic activities showed conclusively that the sulfhydryl and serine residues discussed above do not play an essential role in GPR catalysis (Table 2). Consequently, GPR is neither a cysteine nor a serine protease. We also assayed a variant of P41 in which the site at which P41 autoprocesses to P39 was altered to a sequence different from that recognized by P41. As expected, this variant, ΔP39, did not exhibit detectable conversion to P39 under conditions in which P41 exhibited >70% conversion to P39 (data not shown). The ΔP39 variant also had essentially the same specific activity as P41, indicating that the P41→P39 conversion likely has no role in GPR activity.

TABLE 2.

Enzymatic activities of GPR variantsa

| GPR variant | GPR sp actb |

|---|---|

| P41 S219A | 85 |

| P41 S229A | 103 |

| P41 S274A S276A | 70 |

| P41 C115A | 120 |

| ΔP39 | 97 |

The specific activities of the GPR variants in crude extracts were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Note that all GPR variants were overexpressed to approximately the same level.

The specific activity of the crude extract containing wild-type P41 was set at 100%, and the specific activities of the variants are expressed relative to this value.

Analyses of metal ions in GPR.

Previous work has shown that Ca2+ is required for P41 stability, although Ca2+ is likely not required for catalytic activity (29). However, incubation of P41 as described in Materials and Methods with chelators such as Ophen and HQSA, which have a low affinity for Ca2+ but a high affinity for other divalent cations (i.e., Zn2+), gave no inhibition of GPR activity (data not shown). These results suggest that GPR is not a metalloprotease, which is consistent with the absence of the classical HEXXH motif of metalloproteases from GPR (21, 32). However, it is still possible that GPR is an unusual metalloprotease with a very tightly bound divalent cation. To test this point directly, we dialyzed concentrated GPR solutions against metal-free buffer (except for the stabilizing Ca2+ ions) and analyzed the protein for metal ions by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Analysis of both P41 and P46 showed that Cd2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ were present at <0.03 mol/mol of enzyme subunits, while Zn2+ was present at <0.05 mol/mol of enzyme subunits (data not shown). These data effectively rule out the possibility that GPR is a metalloprotease.

DISCUSSION

Proteases include enzymes that have been classified into four families—aspartic and cysteine proteases, metalloproteases, and serine proteases—as well as a number of unclassified enzymes (2, 18–21). The data in this communication clearly show that GPR is not a cysteine protease, metalloprotease, or serine protease. Presumably, the inhibition of GPR by PMSF was due to reaction with some amino acid residue other than a serine or with a serine residue essential for protein stability but not catalysis. One catalytic residue other than serine that might react with PMSF is threonine, and recently the catalytic residue in the proteasome has been identified as an N-terminal threonine residue (27). While P41 does not have an N-terminal threonine residue, there are nine threonine residues that are conserved in the three known GPR sequences (Fig. 7). Thus, it is formally possible that GPR could utilize a threonine residue for catalysis. However, the proteasome is inhibited by DCI (4), and this inhibitor had no effect on P41. While the latter finding suggests that GPR is not a threonine protease, it remains possible that the highly specific P41 is a threonine protease; further mutagenesis will be required to test this possibility.

The facts that GPR’s pH optimum is ∼8 (28) and that the enzyme is not inhibited by pepstatin also suggest that GPR is not an aspartic protease, as these enzymes are generally active at much lower pH values and are inhibited by pepstatin (20). However, it is formally possible that GPR is an aspartic protease that is active at neutral pH, possibly because of the environment around the active-site aspartates, as has been suggested for several aspartic proteases (5, 25), and perhaps the high specificity of GPR’s active site precludes inhibition by pepstatin. Indeed, while GPRs lack the conserved motifs found in many aspartic proteases, the sequences of GPR from the three species examined do contain seven conserved aspartate residues.

Examination of the GPR sequences for other conserved residues that might be nucleophiles in GPR catalysis reveals one conserved tyrosine, one conserved histidine, one conserved lysine, and five conserved arginines. Although none of these amino acids have been reported to be the direct catalytic residues in proteases, several (e.g., histidine and lysine) participate in catalysis, in particular in serine proteases (19). The lack of inhibition of GPR by NAI suggests that a tyrosine residue does not participate in catalysis (22), but we have as yet no direct proof of the involvement (or lack of involvement) of the other residues. Again, further mutagensis will be required to examine the role of these other residues and to definitively identify the catalytic residues in GPR.

Recently, a substrate-specific protease has been identified in the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis (9). This protease, termed EUO, appears specific for the histone-like proteins which cause chromatin condensation late in this organism’s life cycle, and in this regard EUO displays some similarity to GPR in its biological action. However, EUO differs tremendously from GPR in size, sequence, and inhibition by both pepstatin and a serine protease inhibitor (9).

The present work shows clearly that only the N-terminal two-thirds of GPR is required for both catalytic activity of P41 and autoprocessing of P46 to P41. This is shown not only by the activity and autoprocessing of the 27- to 30-kDa forms generated from P41 and P46 by trypsin digestion but also by the absence of 30 of the C-terminal residues in the Bacillus GPRs from the clostridial enzyme. However, the C-terminal third of the molecule is needed to impart stability at least to P41. It is striking that the C-terminal regions of both P46 and P41 are removed by trypsin cleavage at the same bond (K268). The trypsin sensitivity of the bond between K268 and E269 suggests that these residues are a part of a structure, possibly a loop, that is exposed to the solvent. The loss of the 102 C-terminal residues from P46 without loss of the autoprocessing activity of P30 further suggests that these C-terminal residues form a domain (or domains) which is distinct from the catalytic domain of the enzyme, although the C-terminal domain may be important in stabilizing the intact enzyme. The resistance of P30 to further trypsin digestion is in contrast to the lability of the 27- and 29-kDa forms generated from P41 by trypsin. The degradation and instability of the latter species, the lack of reactivity of the SH group in P30 (in contrast to the SH group in P41), the much greater trypsin sensitivity of P41 than of P46, the lower melting temperature for P41 than for P46, and the greater susceptibility of P41 than of P46 to unfolding by GuHCl are further evidence for a significant difference in tertiary structure between P46 and P41, with the latter presumably having a less compact structure which is less stable and more accessible to DTNB and trypsin. Such a difference in the structure and stability of zymogen and active enzyme has been seen with a number of other proteases, as the zymogen’s propeptide not only helps maintain the enzyme in an inactive state but also assists in the compact folding and stabilization of the protein (15). However, this difference in tertiary structure between these two forms of GPR is not reflected in any significant difference in secondary structure content.

The only major difference between P30 and the larger of the two active forms of P41 generated by trypsin is the presence of most of the propeptide residues in P30. Previous work has shown that removal of 3, 6, or 9 propeptide residues from P46 does not result in an active enzyme and does not cause an increase in the reactivity of the enzyme’s SH group, while removal of 12 residues gives an active enzyme with a more reactive SH group (17). Our new data largely reinforce these earlier results, as (i) the clostridial GPR has only five propeptide residues (analogous to the Δ2-10 variant of B. megaterium GPR), which presumably are sufficient to maintain the enzyme as a zymogen; and (ii) trypsin digestion of the GPR variants lacking 3 or 6 propeptide residues gave results similar to those obtained upon digestion of P46, while trypsin digestion of the variant lacking 12 propeptide residues was like that of P41. In contrast, the Δ2-10 variant has essentially no enzymatic activity (17), as is the case for P46, but trypsin digestion of the Δ2-10 variant gave results similar to those with the active P41. While we cannot explain this discrepancy completely, we note that there is an arginine three residues after the N terminus of the Δ2-10 variant (Fig. 1B). Possibly the propeptide region in the Δ2-10 region is unstable enough that trypsin can cleave at this arginine residue, generating an enzyme that is identical to the Δ2-13 variant that is rapidly degraded by trypsin.

While these results provide further support for the importance of the propeptide in determining GPR structure, they also suggest that most of the propeptide is unlikely to be freely accessible to the solvent, as it is only in the Δ2-10 variant that there may have been significant internal trypsin cleavage in the propeptide. However, the N-terminal region of the propeptide must be solvent accessible, as trypsin does cleave adjacent to K3. This result, as well as the relative stability of the Δ2-7 variant to trypsin and a propeptide of only five residues in the clostridial GPR, indicates that only a few propeptide residues are needed to maintain GPR in the zymogen conformation. Since there is no large conformational change in the P46→P41 conversion, a clear challenge for future work will be to elucidate the precise nature of this conformational change.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are extremely grateful to Douglas Smith of Genome Therapeutics Corporation for providing unpublished genome sequence data. We also thank Donald D. Muccio and Marta Ferraroni for their help with collecting and interpreting the CD spectra and Barbara Setlow for assistance with some experiments.

The AVIV 62DS spectropolarimeter was obtained with funds from NSF grant DIR 8820511. This work was supported by grant GM19698 from the National Institutes of Health (P.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Auld S D. Removal and replacement of metal ions in metallopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:228–242. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett A J. Classification of peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1994;244:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang C T, Wu G-S C, Yang J T. Circular dichroic analysis of protein conformation: inclusion of the β-turns. Anal Biochem. 1978;91:13–31. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg A L. Structure and function of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;65:801–848. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ido E, Han H-P, Kezdy F J, Tang J. Kinetic studies of human immunodeficiency virus type I protease and its active-site hydrogen bond mutant A28S. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24359–24366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. Studies of the processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of spores of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2788–2795. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2788-2795.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. The zymogen of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins of spores of Bacillus species can rapidly autoprocess to the active enzyme in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5571–5573. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5571-5573.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. Autoprocessing of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins of spores of Bacillus species is triggered by low pH, dehydration, and dipicolinic acid. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7032–7037. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7032-7037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaul R, Hoang A, Yan P, Bradbury E M, Wenman W M. The chlamydial EUO gene encodes a histone H1-specific protease. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5928–5934. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5928-5934.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan A R, James M N G. Molecular mechanisms for the conversion of zymogens to active proteolytic enzymes. Protein Sci. 1998;7:815–836. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang X, Bai J, Liu Y, Lubman D M. Characterization of SDS-PAGE-separated proteins by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1996;68:1012–1018. doi: 10.1021/ac950685z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loshon C A, Setlow P. Bacillus megaterium spore protease: purification, radioimmunoassay, and analysis of antigen level and localization during growth, sporulation, and spore germination. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:303–311. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.303-311.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loshon C A, Swerdlow B M, Setlow P. Bacillus megaterium spore protease: synthesis and processing of precursor forms during sporulation and germination. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:10838–10845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muccio D E, Waterhous D V, Fish F, Bronillette C G. Analysis of the two-state behavior of the thermal unfolding of the serum retinol binding protein containing a single retinol ligand. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5560–5567. doi: 10.1021/bi00139a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pace C N, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen L B, Nessi C, Setlow P. Most of the propeptide is dispensable for the stability and autoprocessing of the zymogen of the germination protease of spores of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1824–1827. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1824-1827.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philipps M A, Fletterick R J. Proteases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1992;2:713–720. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawlings N D, Barrett A J. Families of serine peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1994;244:19–61. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rawlings N D, Barrett A J. Families of aspartic peptidases, and those of unknown catalytic mechanism. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:105–120. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rawlings N D, Barrett A J. Evolutionary families of metallopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:183–228. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riordan J F, Vallee B L. O-acetyltyrosine. Methods Enzymol. 1967;11:570–576. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(72)25046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Salas J-L, Santiago-Lara M L, Setlow B, Sussman M D, Setlow P. Properties of mutants of Bacillus megaterium and Bacillus subtilis which lack the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:807–814. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.807-814.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez-Salas J-L, Setlow P. Proteolytic processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2568–2577. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2568-2577.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sankaran K, Wu H C. Bacterial prolipoprotein signal peptidase. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar G, Sommer S S. The “megaprimer” method of site-directed mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1990;8:404–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seemuller E, Lupas A, Stock D, Lowe J, Huber R, Baumeister W. Proteasome from Thermoplasma acidophilum: a threonine protease. Science. 1995;268:579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.7725107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Setlow B, Setlow P. Binding of small, acid-soluble spore proteins to DNA plays a significant role in the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to hydrogen peroxide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3418–3423. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3418-3423.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setlow P. Purification and properties of a specific proteolytic enzyme present in spores of Bacillus megaterium. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:7853–7862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setlow P. Small acid-soluble, spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function and degradation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:319–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setlow P. I will survive: protecting and repairing spore DNA. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2737–2741. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2737-2741.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sussman M D, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis gpr gene, which codes for the protease that initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of spores of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:291–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.291-300.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]