ABSTRACT

Background:

Dissociative disorder is a stress-related disorder usually present in adolescents and younger age groups. It is also accompanied by significant impairment in activity of daily living and family relations. Family environment and use of dysfunctional coping strategies play important roles in the initiation and maintenance of symptoms and this puts a considerable burden on the family.

Objectives:

This study aims to study the presence of stressors, the role of family environment, the role of family burden, and the use of coping mechanisms in persons with dissociative disorder.

Materials and Method:

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study in which 100 persons with a dissociative disorder were included after fulfilling inclusion and exclusion criteria from the outpatient department (OPD) of psychiatry.

Results:

In this study, the major part of the sample were women (87%), most were educated up to 12th standard or less than 12 years of formal education. According to stressors, 44% had family stress/problems. 77% (mostly women) had dissociative stupor. The dissociative disorder caused a considerable degree of burden on the other family members. There was a significant difference in financial burden among caregivers of persons who were married, belonging to rural areas, joint families, and from lower socio-economic classes. There was a significant difference in disruption of routine family activities, and burden in persons having a longer duration of illness. There was a significant difference found in conflict, achievement orientation, and dimensions of family environment between males and females. A significant difference in the venting of emotions, behavioral disengagement, and restraint as a coping strategy between males and females was found.

Conclusion:

Present study showed dissociative disorder patients cause a considerable degree of burden on family members in terms of leisure, physical, mental, financial, and routine family interrelationship domains. In personal growth and relationship dimensions, the use of dysfunctional coping strategies in the family environment has a causal effect on the symptoms of dissociative disorder patients.

Keywords: Conversion disorder, coping pattern, dissociative disorder, family environment, family burden, stressor

Dissociative (conversion) disorder is precipitated by stressful life events or psychological trauma and has a sudden onset.[1] Younger women are mostly affected by this. Various symptoms include convulsions, aphonia, amnesia, and sensory and trans-possession symptoms. Various precipitating factors leading to the occurrence of dissociative disorder include childhood physical or sexual abuse, adulthood trauma, examination stress, conflict with peers or spouse, conflicts in interpersonal relationships, and problems in daily life.[2-4]

Dissociation is related to abusive experiences associated with family environment characteristics. Inflexibility, poor cohesion, dissatisfaction within the family, and difficulties in communication within the family environment are usually associated with the symptomatic group.[5] Clinical characteristics of dissociative disorder patients cause significant burdens on family members. Fazal et al.[6] stated that patients use a variety of coping mechanisms to solve personal and interpersonal problems by seeking to master, minimize, or tolerate stress and conflict. Previous studies have mostly looked into socio-demographic and clinical profiles of persons with dissociative disorders. The current study deals with various dimensions like coping patterns of persons with dissociative disorders, family environment, and family burden.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients selected for the study were after conforming to the diagnosis of dissociative disorder based on the International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 criteria attending the outpatient facility (OPD) in the department of psychiatry at an urban center. Ethics committee approval- 18 Dec 2020.

Sample

A hundred persons with dissociative disorder were recruited for the purpose of the study after taking informed consent. Socio-demographic variables, clinical variables, family environment, family burden, and coping pattern dimensions were assessed using various scales mentioned infra.

Inclusion criteria

Persons of either sex (15–35 age groups) from OPD with a diagnosis of dissociative (conversion) disorder according to ICD-10.

Exclusion criteria

Persons with a seizure disorder, organic brain syndrome, intellectual disability, severe cognitive impairment, substance dependence, learning disabilities, language deficits, severe physical illness, and other syndromal psychiatric comorbidities were excluded.

Tools

Self-designed Proforma

For recording socio-demographic variables.

Clinical profile Proforma

For recording clinical presentation of patients.

Family environment scale

To measure the family environment, the Family Environment Scale (FES) of Moos has been adopted.[7] Joshi and Vyas adopted and standardized it for use in Indian conditions.[8] The original FES questionnaire consists of 90 statements. This scale aims to assess the interpersonal environmental characteristics of families and their perception of the family environment.

Family burden interview schedule (FBIS)

Pai and Kapur, Chakrabarti, Nasr, and others measured the extent pattern of the burden experienced, in relation to the disruption of family leisure, family interaction, and the effect on the physical and mental health of others by family or primary caregivers of patients. Each item is rated on a three-point scale, in which zero is no burden and two is a severe burden.[9-11]

COPE inventory[12]

Coping strategies vary from emotion-focused to problem-focused and from adaptive to less adaptive. It includes 15 different coping patterns, which consist of a 60-item questionnaire based on a four-point scale focusing on the usual frequency of the use of described reactions to stressful events.

RESULTS

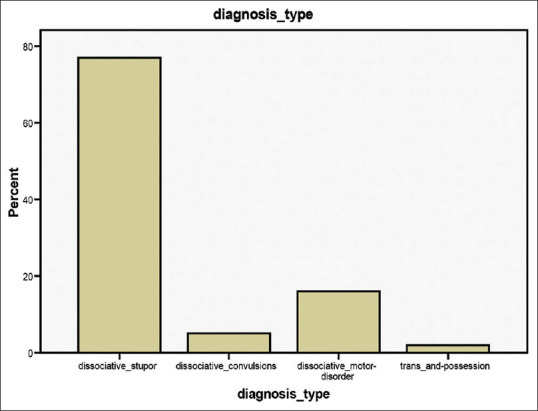

The socio-demographic profile showed that the majority 87 (87%) were females compared to 13 (13%) males. About 54 persons were unmarried and 45 were married, most of them (94%) unemployed. Also, the majority of the patients were educated up to secondary school (59%) out of 100 persons and most of them were from rural backgrounds (59%) [Table 1]. The majority (77%) of patients presented with dissociative stupor, 5% presented with dissociative convulsions, 16% had a dissociative motor disorder, and 2% presented with trans and possession states out of 100 persons with the dissociative disorder [Figure 1]. Of various stressors present, maximum (44) persons presented with stress due to family conflict, 18 persons presented with examination stress, and so on [Table 2]. There was a significant difference between socio-demographic variables locality, employment status, socio-economic class, family type, marital status, duration of illness, and family burden dimensions [Table 3], a significant difference between gender and locality and family environment dimensions [Table 4], a significant difference between gender, age group, duration of illness, and coping patterns [Table 5].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of the dissociative disorder patients

| Demographic variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13 | 13 |

| Female | 87 | 87 |

| Educational status | ||

| Primary | 25 | 25 |

| Secondary | 59 | 59 |

| Graduate-PG | 12 | 12 |

| Illiterate | 4 | 4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 54 | 54 |

| Married | 45 | 45 |

| Living separate | 1 | 1 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 6 | 6 |

| Unemployed | 94 | 94 |

| Place of Residence | ||

| Rural | 59 | 59 |

| Urban | 41 | 41 |

Figure 1.

Diagnostic subcategories

Table 2.

Stressors reported by patients with dissociative disorder

| Stressors | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Family conflict | 44 | 44 |

| Exam academic stress | 18 | 18 |

| Financial stress | 9 | 9 |

| Broken relationship | 9 | 9 |

| Marital discord | 4 | 4 |

| Death of loved ones, loved persons leaving home | 6 | 6 |

| Conflict at school with peers, hostile attitude of teachers | 4 | 4 |

| Stress due to infertility | 2 | 2 |

| No stressor found | 1 | 1 |

| Stress due to fear after seeing last rites of a close person | 1 | 1 |

| Stress due to severe pain during delivery | 1 | 1 |

| Stress due to fear from serious medical condition | 1 | 1 |

Table 3.

Relationship between family burden dimensions and various socio-demographic variables

| Family burden | Place of residence | Mean | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial burden | Rural | 9.01 | 0.012 |

| Urban | 6.60 | ||

| Subjective burden | Rural | 1.86 | 0.002 |

| Urban | 1.70 | ||

|

| |||

| Family burden | Occupation | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| Financial burden | Employed | 11.16 | 0.003 |

| Unemployed | 7.82 | ||

| Subjective burden | Employed | 2.00 | 0.003 |

| Unemployed | 1.78 | ||

|

| |||

| Family burden | Socio-economic class | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| Financial burden | Lower | 9.65 | 0.007 |

| upper | 4.42 | ||

| Subjective burden | Lower | 1.90 | 0.001 |

| Upper | 1.73 | ||

|

| |||

| Family burden | Family type | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| Financial burden | Nuclear | 6.72 | 0.029 |

| Joint | 8.79 | ||

|

| |||

| Family burden dimensions | Marital status | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| Financial burden | Unmarried | 7.16 | 0.001 |

| Married | 8.97 | ||

| Subjective burden | Unmarried Married | 1.74 1.86 | 0.003 |

|

| |||

| Family burden dimensions | Duration of illness | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| Disruption of routine family activities burden | <1 Month | 4.72 | 0.000 |

| >1 Month | 7.38 | ||

| Disruption of family leisure burden | <1 Month | 3.45 | 0.006 |

| >1 Month | 5.19 | ||

| Physical health burden | <1 Month | 0.72 | 0.001 |

| >1 Month | 2.17 | ||

| Mental health burden | <1 Month | 1.31 | 0.000 |

| >1 Month | 2.53 | ||

Table 4.

Relationship between family environment dimensions and socio-demographic profile

| Family environment dimensions | Place of residence | Mean | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Rural | 29.22 | 0.005 |

| Urban | 25.17 | ||

|

| |||

| Family environment dimensions | Gender | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| Conflict score | |||

| Male | 13 | 24.9231 | 0.021 |

| Female | 87 | 24.4023 | |

| Achievement orientation score | |||

| Male | 13 | 13.0769 | 0.039 |

| Female | 87 | 11.0460 | |

| Organization score | |||

| Male | 13 | 29.8462 | 0.012 |

| Female | 87 | 26.2069 | |

| Cohesion score | |||

| Male | 13 | 17.3077 | 0.965 |

| Female | 87 | 14.0575 | |

| Expressiveness score | |||

| Male | 13 | 10.3077 | 0.213 |

| female | 87 | 7.6092 | |

Table 5.

Relationship between coping pattern and socio-demographic profiles

| Coping pattern | Gender | Mean | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venting of emotions | |||

| Male | 13 | 12.0769 | 0.009 |

| Female | 87 | 13.6207 | |

| Behavioral disengagement | |||

| Male | 13 | 7.4615 | 0.009 |

| Female | 87 | 10.2989 | |

| Restraint | |||

| Male | 13 | 4.4615 | 0.002 |

| Female | 87 | 5.8276 | |

|

| |||

| Coping pattern | Age category | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| 1. Positive interpretation and growth | >=24 | 4.11 | 0.023 |

| <24 | 4.00 | ||

| 2. Religious coping | >=24 | 13.28 | 0.021 |

| <24 | 10.37 | ||

| 3. Restraint | >=24 | 6.09 | 0.011 |

| <24 | 5.32 | ||

| 4. Acceptance | >=24 | 11.73 | 0.016 |

| <24 | 9.22 | ||

|

| |||

| Coping pattern | Duration of illness | Mean | P |

|

| |||

| 1. Positive interpretation and growth | < 1 Month | 4.31 | 0.001 |

| >1 Month | 3.97 | ||

| 2. Acceptance | <1 Month | 9.04 | 0.019 |

| >1 Month | 10.62 | ||

DISCUSSION

In this study, the majority of persons were females (87%) than males (13%) similar to the studies by Vyas, Bagadia, and Choudhury et al.[13-15] Literacy level was 96% in most of the subjects as they had completed 12th or less than 12 years of formal education in spite of being literate. The detailed inquiry as to why they did not pursue their education was not inquired into. Unmarried persons constitute the majority of our sample (54%), in contrast with the findings of Verma and Jain.[16] and Choudhury et al.[15] who found the majority of married persons in their studies. As many as 59% of subjects were from rural backgrounds which is not consistent with the work of Deveci et al.[17] 63% of subjects are from joint families, which is in agreement with the study by Vyas et al.[13] The majority of our subjects are from middle and lower socio-economic status (81%) and the majority of them are unemployed (94%). Irrespective of literacy level or community status, the majority of our subjects presented with dissociative stupor (77%). This is in contrast to the findings of Roelfs et al.[18] study in which the commonest clinical presentation was paresis/paralysis.

The critical focus of this study was the presence of stressors, family environment, and family burden. Stressors were present in the majority of dissociative disorder patients which is consistent with the findings by Dar and Hasan (2018).[19] It was found the majority of patients (44%) presented with some family stress/problems. Females were in majority as compared to male subjects in our study, which is similar to findings in other studies.[20] As far as the family environment is concerned, it was found that males scored significantly higher in conflict and organization dimensions as compared to females in the present study; this indicated that the organizational skills of the family members of the male dissociative patients were found to be better. The subjects scored average in the organization dimension, which shows to have a balanced organization and less conflict in the family environment, which in turn indicated that subjects were more comfortable with family members. The family of dissociative disorder patients scored below average in cohesion and expressiveness dimensions, whereas conflict was found to be above average. Dissociative disorder patients scored below average in achievement orientation and independence.[21] Control in dissociative disorder patients is very intellectual and strong, i.e., the rigidity of family rules, the extent to which the family activities are organized hierarchically, etc., In the present study, control was significantly higher among the family environment of persons belonging to rural areas. Conflict, achievement orientation, and organization were higher among the male group of patients.

The findings in this study could be because women are not allowed to interact and socialize in society, particularly because of the cultural and religious orientation of our society. Although many previous studies were conducted in India and elsewhere, the findings of the present study cannot be comparable because of the lack of similar work in this area. In this study, there was no statistically significant difference between the caregivers of male and female groups in terms of family burden dimensions. A study assessed the burden of care among caregivers and substance use groups (opioids and alcohol). There was no significant difference between the groups, however, the result was severe in all domains.[22]

It is well established that a high degree of burden is associated with women, old age, low-educational level, those who are unemployed, and caregivers of younger persons.[23] A significantly higher degree of financial and subjective burden among caregivers in persons belonging to rural areas, those who are employed, from lower socio-economic classes, belonging to joint families, and those who were married was found in this study. Disruption of routine family activities, family leisure burden, and physical and mental health burden were significantly higher with the duration of illness >1 month among caregivers were the other findings. Hence, it can be said that there is some kind of burden over the family, be it a financial burden, a burden on the physical or mental health of another family member, or family leisure burden, or a disturbance in the relationship between the family members of persons with dissociative disorder.

Females most commonly used venting of emotions, behavioral disengagement, and restraint as coping mechanisms in this study. Persons with age >24 years used positive interpretation, religious coping, restraint, and acceptance as the most common coping mechanisms. Persons with a duration of illness >1 month used most commonly acceptance as a coping mechanism when compared to a study by Ahmed and Bokharey where it was found that dissociative conversion disorder had low trait resilience and used a greater number of dysfunctional coping strategies.[24]

As per the gender difference, there were no differences between sexes in competitive propensities in many other studies.[25] According to a study by Riffin et al., 2017,[26] women scored significantly higher in cohesion and conflict dimensions. In addition, females scored significantly higher in recreational and moral orientation as compared to males. In our study, the expressiveness mean score was 7.96 which was found below average and the difference was not found to be statistically significant between either sex in another study by Grant.[27] This indicates that subjects feel more comfortable with their family members in expressiveness, which gives them motivation towards better accomplishment in their work environment. The independence mean score in our study was 13.23 in males and 12.71 in the female group. Findings by Horai and Tedeschi revealed that there was no difference between gender.[28] As per the independence dimension, those who scored less in independence dimensions ultimately feel more psychologically better in dealing with day-to-day stress in work and family situations. According to another supportive study by Monin and Schulz, multiplied responsibility for the suffering of a loved one may place family members at greater risk of adverse outcomes, above and beyond the physical demands of care provision which indicates a lower level of independence.[29]

Another FES dimension was the moral emphasis. The mean score was 29.84 in males and 27.21 in females which indicates better in happiness, truthfulness, and peace among family members. A study by Riffin et al.[26] showed females scored significantly higher in moral and recreational orientation. Similar findings were found by Watson and Hoffman who found that no differences were there between male and female groups which is similar to the finding in the present study.[25] Nature and qualitative orientation of the personnel may account for these. Moral issues in the family are enhanced by deep-rooted support for the family members, which helps them to work productively.

Limitations

The small sample size, purposive sampling technique, and cross-sectional design were some of the limitations of the study.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of dissociative symptoms is related to low cohesion, expressiveness, and negative conflicts in the family in addition achievement orientation, organization played an important role in persons with dissociative disorder leading to the occurrence of dissociative symptoms. Persons with dissociative disorder cause a considerable degree of burden on the family in terms of leisure, physical, mental, financial, and family relationship domains. The use of dysfunctional coping strategies leads to the maintenance of symptoms of persons with dissociative disorder. An understanding of the precipitating psychosocial factors that overwhelm the patients coping abilities has implications for treatment and enables clinicians to devise specific strategies for early intervention and prevention. Future studies should be conducted with large sample sizes and prospective study designs with a comparison group.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tessner KD, Mittal V, Walker EF. Longitudinal study of stressful life events and daily stressors among adolescents at high risk for psychotic disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:432–41. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sajid WB, Rashid S, Jehangir S. Hysteria: A symptom or a syndrome. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2005;55:175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foote B, Smolin Y, Kaplan M, Legatt ME, Lipschitz D. Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:623–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman ES, Markand ON. Psychodynamics and psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:57–63. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MNS, Ahmad S, Arshad N. Birth order, family size and its association with conversion disorders. Pak J Med Sci. 2006;22:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazal S, Vivek K, Dollen H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in the western country: Systematic review and metaregression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moos RH. Conceptual and empirical approaches to developing family-based assessment procedures: Resolving the case of the Family Environment Scale. Fam Process. 1990;29:199–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1990.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi MC, Vyas OP. Hindi adaptation of Family Environment Scale: rupa psychological centre, Varanasi. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pai S, Kapur RL. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: Development of an interview schedule. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:332–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakrabarti S, Raj L, Kulhara P, Avasthi A, Verma SK. Comparison of the extent and pattern of family burden in affective disorders and schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 1995;37:105–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasr T, Kausar R. Psychoeducation and the family burden in schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–83. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vyas JN, Bhardwaj PK. A study of hysteria- AN analysis of 304 patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagadia VN, Shastri PC, Shah JP. Hysteria: A study of demographic factors. Indian J Psychiatry. 1973;5:179. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choudhury S, Bhatia MS, Mallick SC. Hysteria in female hospital: Paper presented at 48th Annual National conference of Indian Psychiatric Society, 1996. :3225. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma KK, Jain A. Is hysteria still prevailing?“A retrospective study”Paper Presented in 52nd Annual Conference of Indian Psychiatric Society, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deveci A, Taskin O, Dinc G, Yilmaz H, Demet MM, Dundar P, et al. Prevalence of pseudo neurologic conversion disorder in an urban community in Manisa, Turkey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:857–64. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roelfs K, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin KA, Naring GW, Moene FC. Childhood abuse in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1908–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dar LK, Hasan S. Traumatic experiences and dissociation in patients with conversion disorder. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68:1776–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi JK, Singh H, Sinha PK. A clinical study of hysteria in children and adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:70–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinter M, Boss PG, Johnson N. The relationship between dysfunctional family environments and family member food intake. J Marriage Farm. 1981;43:633–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shareef N, Srivastava M, Tiwari R. Burden of care and quality of life (QOL) in opioid and alcohol abusing subjects. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;2:880–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh K, Kumar R, Sharma N, Nehra DK. Study of burden in parents of children with mental retardation. J Indian Health Psychol. 2014;8:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad QA, Bokharey IZ. Resilience and coping strategies in the patients with conversion disorder and general medical conditions: A comparative study. Malays J Psychiatry. 2013;22:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson C, Hoffman LR. Managers as negotiators: A test of power versus gender as predictors of feelings, behavior, and outcomes. Leaders Q. 1996;7:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riffin C, Fried T, Pillemer K. Impact of pain on family members and caregivers of geriatric patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:663–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant MJ, Sermat V. Status and sex of other as determinants of behavior in a mixed-motive game. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1969;12:151–7. doi: 10.1037/h0027573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horai J, Tedeschi JT. Compliance and the use of threats and promises after a power reversal. Behav Sci. 1975;20:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monin JK, Schulz R. Interpersonal effects of suffering in older adult caregiving relationships. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:681–95. doi: 10.1037/a0016355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]