Extended Data Figure 2: PFNd tuning properties.

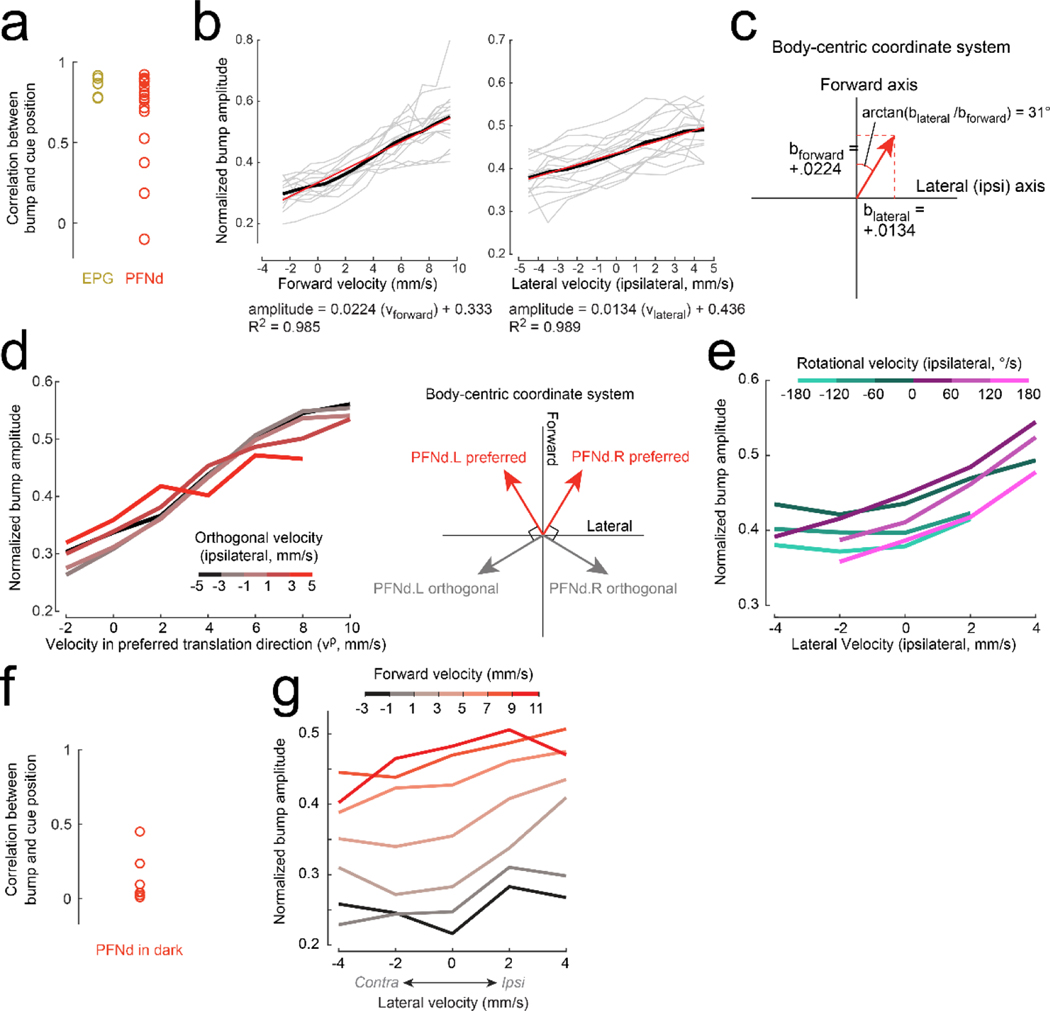

a. Circular correlation between bump and cue position for PFNd (n=16 flies) and EPG neurons (n=5 flies). Note that PFNd bump position is not as correlated with heading as EPG activity is. This is because PFNd neurons conjunctively encode velocity and heading, whereas EPG neurons encode only heading. For example, when the fly walks forward right, the PFNd bump on the left diminishes in amplitude, and vice versa. When the left and right bumps have different amplitudes, this diminishes the accuracy of our estimate of the bump position. Moreover, when the fly steps backward, both PFNd bumps diminish in amplitude, which again makes it difficult to accurately estimate bump position.

b. Normalized PFNd PB bump amplitude versus forward velocity (left), and lateral velocity (right). Gray lines are individual flies and the black line is the mean across flies (n=16 flies). Data from the right and left PB are combined, and lateral velocity is computed in the ipsilateral direction (so that, for PFNd.L neurons, leftward lateral velocity is positive and rightward lateral velocity is negative). The red line shows the linear fit to the mean line, with the fitted equation below each plot.

c. Computation of preferred translational direction angle using the linear regression slopes for forward and lateral velocity. We used the ratio of the slopes of the linear fits to lateral and forward velocity to calculate the angle of preferred translational direction.

d. PFNd data from Fig. 1g, re-plotted in polar coordinates. Here, normalized bump amplitude is displayed as a function of body-centric translation direction and binned by speed.

e. Normalized PFNd bump amplitude versus velocity in the preferred translational direction (vp). Data from the right and left PB are combined and binned by the fly’s velocity orthogonal to the preferred translational direction (see schematic at right). Shown is the mean across flies (n=16 flies). Note that a positive value in the orthogonal axis is in the ipsilateral direction. Whereas there is a significant effect of velocity in the preferred direction (2-way ANCOVA, P<10−10), there is no significant effect of velocity in the orthogonal direction (p=0.97).

f. Normalized PFNd bump amplitude versus lateral velocity in the ipsilateral direction. Data from the right and left PB are combined, binned by ipsilateral rotational velocity, and averaged across flies (n=16 flies). Whereas there is a significant effect of lateral velocity (2-way ANCOVA, P<10−10), there is no significant effect of rotational velocity (p=0.59). This analysis shows that there is little or no systematic relationship between PFNd activity and rotational velocity once we account for the effect of lateral velocity. Note that, because rotational and lateral velocity are correlated, rotational velocity bins are asymmetrically populated.

g. Circular correlation between bump and cue position for PFNd neurons when the fly walks in darkness (n=7 flies).

h. Normalized bump amplitude versus lateral velocity in the ipsilateral direction, binned and color-coded by forward velocity, for PFNd neurons when the fly walks in darkness (n=7 flies). Lateral velocity is measured in the ipsilateral direction, and data from the right and left PB are combined and then averaged across flies. Both forward and lateral velocity have a significant effect (2-way ANCOVA, P<10−10 and P<10−5).