Abstract

Aims:

Transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TCMS) is successful in decreasing pain in several neurologic conditions. This multicenter parallel double-blind phase II clinical trial is a follow up to a pilot study that demonstrated pain relief in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) treated with TCMS.

Methods:

Thirty-four participants with confirmed DPN and baseline pain score ≥5 were randomized to treatment at two sites. Participants were treated with either TCMS (n=18) or sham (n=16) applied to each foot once a week for four weeks. Pain scores using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale after 10 steps on a hard floor surface and answers to Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System pain questions were recorded by participants daily for 28 days.

Results:

Thirty-one participants completed the study and were analyzed. Average pain scores decreased from baseline in both groups. The difference in pain scores between TCMS and sham treatments was −0.52 and +0.24 for left foot morning and evening and −0.25 and −0.41 for right foot morning and evening. Moderate adverse events that resolved spontaneously were experienced in both treatment arms.

Conclusion:

In this two-arm trial, TCMS failed to demonstrate a significant benefit over sham in patient reported pain suggesting a substantial placebo effect in our previous pilot study.

Keywords: Transcutaneous magnetic stimulation, Diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Pain, Type 2 diabetes, Type 1 diabetes

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic disorders worldwide affecting approximately 537 million people according to the International Diabetes Federation1. Complications due to diabetes result in substantial morbidity and mortality for patients. The most prevalent complication in individuals with diabetes is peripheral neuropathy. It develops in approximately 50% of patients with diabetes and typically affects distal nerve endings in the hands, feet, and legs2. In addition to being the most common complication of diabetes, diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) significantly affects patients’ quality of life with pain, hindered activities of daily living3, increased fall risk4, disrupted sleep5,6, and negative effects on mental health7,8. Further, peripheral neuropathy is undermanaged, in part, due to the dearth of safe and effective treatments. There are no approved disease modifying therapies9 and sustained pain relief only occurs in a small percentage of patients. Pharmacologic treatment achieves greater than 50% pain relief in less than one third of individuals with painful DPN10. In addition, pharmacotherapy is often limited due to the side effect profile, contraindications, and concerns for misuse11. Current strategies focus on symptomatic management with analgesia and tight glycemic control, which has limited benefit and slows the progression of neuropathy in some patients, mainly individuals with type 1 diabetes12. There is an unmet need for treatment of DPN that can better address pain and enhance quality of life.

Transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TCMS) is a treatment modality that has gained recognition in recent years for pain management. TCMS delivers magnetic pulses across the skin to induce the electrical stimulation of nerves and can be delivered centrally to the brain, as is the case in transcranial magnetic stimulation, or peripherally at target sites. The means by which repetitive magnetic stimulation alters pain sensation is not well understood13. Centrally delivered magnetic stimulation alters cortical excitability14 while peripherally directed therapy is thought to modulate both peripheral and central neural excitability15,16. Despite its unclear mechanism, TCMS has shown efficacy in providing analgesia for migraines17, fibromyalgia18, osteoarthritis19, and various types of neuropathic pain20. In the context of diabetes, transcranial magnetic stimulation demonstrated relief of lower limb pain following five consecutive days of treatment21. When targeted to the feet, however, TCMS has so far utilized low intensity magnetic fields (50–10,000x lower than transcranial magnetic stimulation) and has displayed mixed results in terms of pain and quality of life improvement22–26. A pilot study demonstrated significant pain relief utilizing high intensity TCMS, similar in magnitude to transcranial magnetic stimulation, for treatment of DPN27. The aim of this study was to assess the effect of high intensity (1.2 Telsa) TCMS vs. sham control in treating foot pain due to DPN.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The trial tested the safety and efficacy of recurrent TCMS on patient-reported foot pain caused by DPN at two sites in the United States, using a randomized double blind parallel two-arm study design. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both sites, and informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

The TCMS treatment plan was based on preliminary data, which demonstrated significant decreases in pain lasting one week after a one-time TCMS treatment to the feet28. Treatments were administered on days 0, 7, 14, and 21 by study investigators utilizing the Pulse V1.0 device (Figure 1). TCMS treatment consisted of four weekly sessions of 1.2 Tesla magnetic pulses delivered to the plantar surface of the foot. The anterior and posterior halves of each foot were treated separately such that each half foot received 50 pulses with a 6 second pulse interval over 5 minutes. This was done to ensure consistency in treatment received between participants with different foot sizes. Sham treatments were administered using the same device. When the device was switched to sham mode, a treatment sound was produced every 6 seconds without delivering magnetic pulses. The device automatically ended treatment after 5 minutes and treatment duration was recorded to ensure consistency. Following TCMS or sham treatment, participants waited 5 minutes before assessment of pain.

Figure 1. Pulse V1.0 Device.

(A) TCMS and sham treatments were administered using the device. Participants placed their feet, one at a time on the device platform. Each foot received two 5-minute treatments with the foot positioned over the anterior blue dot followed by the posterior blue dot. (B) Electrical pulses are delivered to the foot via a magnetic coil.

Participants were randomly assigned to treatment groups using block randomization with a block size of 20 at each of the two sites. Assignments were placed in sealed envelopes by an independent statistician. Envelopes were opened prior to the first treatment session by the investigator administering treatment. Separate investigators enrolled patients/recorded responses and administered treatments in accordance with a double-blind study design.

Pain was measured using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) (0 to 10, 0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain) after 10 steps in stocking feet on a hard floor surface, which was termed the Standard Pain Measurement Walk (SPMW). Following treatment, pain scores were collected from each foot. Medication usage, non-drug treatments, and functional status over the prior week were also noted. Prior to enrollment and between treatments, participants recorded daily morning/evening (within 2 hours of waking and sleeping) NPRS pain scores and answered Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain questions (Supplemental 1) regarding pain interfering with daily activities, social activities, and sleep. Data was recorded in a logbook by participants daily and reported to blinded investigators over the phone weekly. Logbooks were compared to phone reported scores by blinded investigators weekly prior to treatment sessions. Adverse events were recorded between and following treatments.

2.2. Eligibility

Volunteers who were at least 18 years of age who had pain associated with chronic bilateral DPN located in the feet were enrolled. For inclusion, the pain could not be explained by central anatomic nerve compression and needed to clearly correlate with the participant’s history of diabetes. Additionally, volunteers needed to have a baseline pain intensity ≥ 5 on SPMW for 3 days at the time of enrollment and the pain had to occur daily for more than one month. The SPMW was explained to participants by study investigators, performed and recorded by participants at home, and reported to study investigators to determine baseline pain intensity. Volunteers who were unable to undergo an MRI (due to potential effects of magnetic pulses on any implanted hardware), walk 10 steps, or independently complete study assessments were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included a life expectancy ≤ 6 months, another pain condition that might confound results, open wound/ulcer on either foot, metal hardware in either ankle or foot, uncontrolled psychological comorbidities, use of opioid, benzodiazepine, or psychotropic medication for treatment of foot pain, pregnancy, and a recent change in the class or the dose (≥ 20%) of pain medication.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the average difference in NPRS pain score from baseline in TCMS and sham treated individuals over time. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of responders, individuals who achieved a pain reduction of 2 or more points within the first week of treatment, as well as the change in PROMIS quality of life scores. Study success was defined as a statistically significant reduction in pain between TCMS and sham groups that has a clinically relevant difference of 2 or more points. Adverse events were closely followed throughout the duration of the trial.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The mean change in pain scores and PROMIS quality of life scores were compared between TCMS and sham treatment groups using a mixed models repeated measures analysis of variance. Differences in the percentage of responders were evaluated using a Fisher’s exact test. Baseline characteristics were assessed with Fisher’s exact and t-tests. A sample size of 40 was determined based on power analysis calculations using data from the pilot study and an estimated placebo effect of 35% (alpha = 0.05, beta = 0.2, enrollment ratio = 1:1, effect size = 2, standard deviation = 2.11). Placebo effect was estimated based on previous studies of DPN24,25.

2.5. Funding

Funding for the TCMS device was provided by Zygood, LLC. Study data were independently collected and analyzed by investigators.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

Between February 2020 to December 2021, a total of 60 participants were screened between the two sites, of which 34 were randomly assigned to receive TCMS (18 participants) or sham (16 participants) treatment, and 31 completed the study (Figure 2). All participants who completed the study were present for all four treatment sessions outside of one participant who missed one treatment session. Three participants did not complete the study; two due to Covid-19 infection and one due to early termination of the trial. Baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the two treatment groups (Table 1). Only one participant in the TCMS group had a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes; all other participants had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. The mean duration of diabetes was over ten years with an average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (within the last three months) of 8.09% for the TCMS arm and 8.69% for the sham arm. At least three fourths of the participants in both groups were taking neuropathic pain medications during the trial.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population (Mean ± SD)

| Participant Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Sham Group (N = 14) | TCMS Group (N = 17) | P-Value | |

| Age (yr) | 58.08 ± 13.61 | 57.94 ± 8.31 | 0.975 |

| BMI | 29.47 ± 3.89 | 31.07 ± 7.65 | 0.495 |

| Female sex (%) | 57.14 | 52.94 | 1.000 |

| Race (%)a | 0.691 | ||

| Black | 57.14 | 62.50 | |

| White | 35.71 | 18.75 | |

| Asian | 7.14 | 12.50 | |

| Other | 0.00 | 6.25 | |

| Type 2 DM (%) | 100 | 94.12 | 0.9213 |

| HbA1cb | 8.69 ± 2.31 | 8.092 ± 2.10 | 0.495 |

| Years since DM diagnosisc | 11.58 ± 6.88 | 17.11 ± 11.74 | 0.1537 |

| Current neuropathic pain medications (%) | 78.57 | 76.47 | 1.00 |

Race was not reported for one TCMS participant.

HbA1c was not available for four TCMS participants and one sham participant.

Years since diabetes diagnosis was not reported from one sham participant.

3.2. Primary outcome

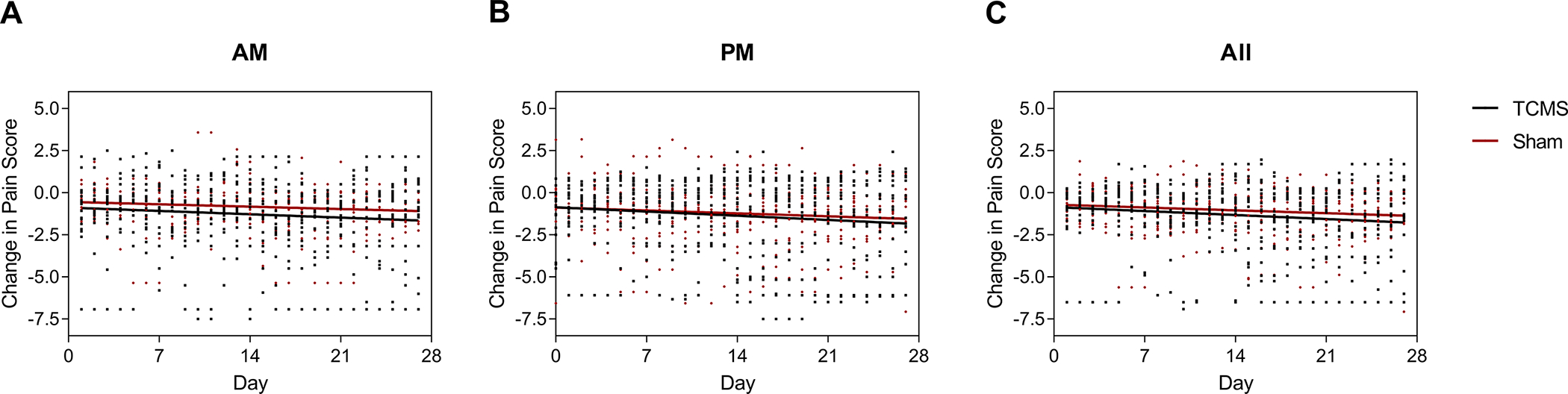

Prior to treatment, the baseline pain score in each foot was measured in the morning and evening for at least three days. Mean baseline pain scores were significantly lower in the morning (p=0.002), but did not differ between feet (p=0.89), and there was no interaction between the two variables (p=0.93). Importantly, baseline pain scores were similar between treatment groups (Table 2). Over the 28-day trial period, mean right and left foot pain scores in the morning and evening were separately compared between treatments. Average pain scores decreased from baseline in all conditions regardless of side, time, or treatment (Figure 3). The decrease in pain score with TCMS treatment compared to sham was not significantly different between treatments for morning (p=0.37), evening (p=0.90), or overall pain scores (p=0.62).

Table 2.

Mean NPRS Scores by Time

| Treatment Group | AM | PM | Overall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Sham | 6.79 ± 1.92 | 7.69 ± 1.53 | 7.24 ± 1.48 | |

| TCMS | 6.87 ± 1.87 | 7.86 ± 1.43 | 7.36 ± 1.22 | ||

| P-Value | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.80 | ||

| Final | Sham | 6.00 ± 1.97 | 6.23 ± 2.09 | 6.12 ± 1.95 | |

| TCMS | 5.53 ± 3.34 | 6.28 ± 3.25 | 5.90 ± 3.21 | ||

| P-Value | 0.65 | 0.96 | 0.83 | ||

| Sham Subtracted Change | −0.55 | −0.13 | −0.34 | ||

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Figure 3.

Mean Pain Scores for TCMS vs. Sham Treatments. Pain scores (n=31) were recorded on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) following a Standard Pain Measurement Walk (SPMW). Pain scores over time of participants receiving TCMS or sham therapy are displayed for morning (A), evening (B), overall (C). Each symbol (circle or square) represents a daily pain score for one participant. Trend lines are also displayed.

The study was halted after an interim analysis showed that criteria for study success were not met. No comparison displayed a pain reduction difference of at least two points between TCMS and sham regimens. In the TCMS group, the mean change in pain score from baseline across all days was −1.34 (95% CI, −2.56 to −0.12) for morning, −1.58 (95% CI, −2.84 to −0.32) for evening, and −1.46 (95% CI, −2.62 to −0.30) overall. With sham treatment, the mean change in pain score from baseline across all days was −0.79 (95% CI, −1.31 to −0.27) for morning, −1.45 (95% CI, −2.79 to −0.12) for evening, and −1.12 (95% CI, −1.86 to −0.38) overall. This amounts to a sham subtracted TCMS effect of −0.55 for morning, −0.13 for evening, and −0.34 overall. Mean pain scores on the final day of the study also did not differ between treatment groups (Table 2).

3.3. Secondary outcomes

The percentage of responders and the change in PROMIS quality of life scores did not differ between TCMS and sham treated participants. In the TCMS arm, 63.16% of participants responded to the first treatment compared to 36.84% in the sham arm (p=0.70). Likewise, TCMS treatment did not improve pain quality of life scores as related to daily activities (p=0.33), social activities (p=0.38), or sleep (p=0.29) relative to sham. Additionally, the immediate effect of TCMS treatment was quantified. The average difference in pain score before and 5 minutes after TCMS treatment was −1.90, which constitutes a −0.85 sham subtracted TCMS effect (p=0.13). This difference in pain score following TCMS treatment decreased over time (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Difference in pain score before and 5 minutes after treatment. The average difference in pain score between the morning before and 5 minutes after treatment is displayed for participants treated with TCMS or sham. Pain scores for each foot were recorded on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) following a Standard Pain Measurement Walk (SPMW) and then averaged.

3.4. Safety

A total of ten mild to moderate adverse events possibly related to treatment were experienced by six participants, four TCMS and two sham treated. These events were mainly itching or twitching sensations and increases in pain (Table 3). All adverse events resolved spontaneously, outside of one TCMS treated patient who had persistently increased pain in both feet.

Table 3.

Adverse Events

| Treatment | Days after treatment | Duration (days) | Severity | Outcome | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sham | 3 | 5 | mild | Resolved | Tingling |

|

| |||||

| TCMS | 5 | 1 | mild | Resolved | Itching |

| 0 | 0 | mild | Resolved | Itching | |

| 4 | 5 | mild | Resolved | Twitching | |

|

| |||||

| TCMS | 0 | 0 | moderate | Resolved | Sharp pain |

|

| |||||

| TCMS | 0 | 0 | mild | Resolved | Tingling |

| 1 | 0 | mild | Resolved | Sharp pain | |

|

| |||||

| Sham | 0 | 0 | mild | Resolved | Tightness |

|

| |||||

| TCMS | 0 | 0 | moderate | Resolved | Increased pain |

| 0 | 28 | mild | Not resolved | Worsened peripheral neuropathy | |

4. Discussion

Non-pharmacologic treatments for painful DPN are being developed to provide improved efficacy with lower risk of adverse events. This trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of TCMS in the treatment of DPN using a randomized double blind two-arm study design at two outpatient centers. Peripherally delivered TCMS appears to be a safe treatment modality for DPN. The TCMS device used in this study shares technology with an FDA FDA transcranial magnetic stimulation device for migraine treatment in which no notable adverse events have been observed28. As expected, no significant adverse events related to TCMS treatment were detected in this trial during the 28 day follow up period.

In terms of efficacy, neither the primary nor secondary outcomes were achieved in this study. The sham subtracted improvements in TCMS treated individuals were minimal (−0.55 to −0.13). Interestingly, the sham subtracted TCMS effect on left foot pain scores increased over time (data not shown), which suggests that a clinically important difference may be observed with increased frequency/duration of treatment. However, a similar effect would be expected for right foot pain scores and was not seen in this study. It is unclear why differential effects are observed between feet, although the overall effect size was small and likely due to chance. The sham subtracted TCMS effect was also variable with respect to time of day. Our finding that baseline pain scores are greater in the evening than morning is a well-documented observation for diabetic neuropathy29,30. Given participant’s greater baseline pain score at night, it is plausible that time of day influences a person’s perception of pain as well as the effect of TCMS treatment.

Another remarkable finding was the sustained drop in pain score following the first treatment session. The first treatment was administered prior to measuring daily AM and PM pain scores. Relative to baseline pain, the first recorded daily pain score decreased by approximately one point for all time, side, and treatment groups indicating a considerable placebo effect. Previous studies investigating the effect of magnetic stimulation on neuropathic pain have also detected placebo effects of varying magnitude. The placebo effect has been reported to account for between 4 and 41% reduction in pain immediately following repetitive treatment of at least three weeks in duration23–25. In this study, the average placebo effect across all days was 11.5% and 14.5% immediately following treatment.

The findings from this study are in stark contrast to those from our previous pilot study28. Although the preceding pilot study did not include a placebo arm, there was a 78% pain reduction immediately following TCMS therapy. This is much greater than the 34% reduction observed in this study. Possible explanations for this decreased effect include differences in the study population and methodology. Compared to the population in the pilot study, participants in this study had greater average baseline pain scores (7.34 ± 1.25 vs. 5.72 ± 0.97, p=0.0025). It seems reasonable that later in the disease process, individuals are less likely to benefit from TCMS as the damage to the nervous system becomes irreversible31,32. To our knowledge, no clinical studies to date have compared the effect of TCMS in individuals with early and late stage DPN. Another major difference between the two studies was the site at which treatment was administered to the feet of participants. In the pilot study, treatment was administered to both the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the foot while only the plantar surface was treated in this study. The reasoning behind this change was based on our own observations that treatment of the dorsal surface of the foot had minimal effects on pain score.

Our pilot also demonstrated that the greatest pain reduction occurred soon after TCMS administration. As such, in this trial, we compared changes in pain scores the morning prior to TCMS therapy and 5 minutes after therapy for each of the four weekly treatment sessions. While the average decrease in pain score did not differ significantly from sham treatment, the effect of TCMS appeared to wane across the four treatment sessions. The sham effect across these sessions was constant. This decreased effect of TCMS over time suggests either an improvement in participants’ reported pain or physiologic compensation. In support of an improvement in pain is the increased variation of pain score in the TCMS group at the end of the study. The standard deviation in pain score in the TCMS group at the beginning of the study, the sham group at the beginning of the study, and the sham group at the end of the study are all similar. In contrast, the standard deviation of the TCMS group at the end of the study is approximately two times larger. This indicates a potential subset of patients who responded to therapy. Unfortunately, our study was not powered for subgroup analyses. Future studies may provide more insight.

4.1. Study Limitations

This study was stopped prematurely after a preliminary analysis did not show a clinically significant decrease in pain with TCMS treatment. The decision to perform a preliminary analysis was made due to slow patient accrual during the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, the actual study size was below the estimated sample size, though this is very unlikely to have changed the study findings. A much larger sample size would have allowed for subsequent subgroup analyses. Additionally, more frequent treatment or a longer study duration may have been beneficial in uncovering small effects of TCMS treatment. Another shortcoming of this study was that the quality of pain was not assessed. A complimentary questionnaire such as the neuropathic pain scale may have been helpful in this regard. Lastly, although we believe the placebo effect was appropriately controlled for in this study, magnetic stimulation may have been felt by individuals. It is unclear whether participants knew which treatment they received and if this affected their pain scores, however, a greater reduction in pain may be anticipated if individuals believed they were in the active treatment arm.

5. Conclusions

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy remains a challenging condition to manage. TCMS has previously shown potential benefit in the treatment of DPN related pain in a small single arm study. However, this two-arm study comparing TCMS to sham failed to demonstrate a significant between-group difference in the reported pain reduction, suggesting a significant placebo effect in the previous study. Additional studies designed for subgroup analyses may identify specific populations that would benefit from TCMS treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Kathleen Palmer for coordinating treatment visits, David Lear for assisting in treatment administration, and Devon Nwaba enrolling participants and collecting patient reported outcomes.

Funding:

This study was funded by Zygood, LLC. NIH Fellowship Grant F30DK124986 supported VPR.

Abbreviations:

- DPN

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

- TCMS

Transcutaneous Magnetic Stimulation

- TMS

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

- NPRS

Numeric Pain Rating Scale

- SPMW

Standard Pain Measurement Walk

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Disclosures: No authors have any competing interests.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and Georgetown-MedStar Institutional Review Board and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Availability of data and material: Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code availability: Not applicable

Consent for publication: The manuscript is approved by all named authors and the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all authors.

Trial registration: TCMS for the Treatment of Foot Pain Caused By Diabetic Neuropathy, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03596203, ID- NCT03596203

Contributor Information

Vishnu P. Rao, University of Maryland, School of Medicine, 800 Linden Avenue, altimore, MD, 21201, 443-682-6800.

Yoon Kook Kim, University of Maryland, School of Medicine, 800 Linden Avenue, Baltimore, MD 21201, 443-682-6800.

Anahita Ghazi, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science Medical Sciences, 3333 Green Bay Road, North Chicago, IL 60064, 847-578-3000.

Jean Y. Park, MedStar Medical Group, 5601 Loch Raven Blvd., Floor 3, Baltimore, MD, 21239, 443-444-5663.

Kashif M. Munir, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, Address: 800 Linden Avenue, 8th floor, Division of Endocrinology, Baltimore, Maryland, 21201.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyck PJ, Kratz KM, Karnes JL, et al. The prevalence by staged severity of various types of diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy in a population-based cohort: The Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study. Neurology. 1993;43(4):817–817. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.4.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Win MMTM, Fukai K, Nyunt HH, Hyodo Y, Linn K. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy and its impact on activities of daily living in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nurs Health Sci. 2019;21(4):445–453. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson JK, Hurvitz EA. Peripheral Neuropathy: A True Risk Factor for Falls. J Gerontol Ser A. 1995;50A(4):M211–M215. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50A.4.M211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gore M, Brandenburg NA, Dukes E, Hoffman DL, Tai KS, Stacey B. Pain Severity in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy is Associated with Patient Functioning, Symptom Levels of Anxiety and Depression, and Sleep. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(4):374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zelman DC, Brandenburg NA, Gore M. Sleep Impairment in Patients With Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(8):681–685. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210910.49923.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dermanovic Dobrota V, Hrabac P, Skegro D, et al. The impact of neuropathic pain and other comorbidities on the quality of life in patients with diabetes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0171-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vileikyte L, Leventhal H, Gonzalez JS, et al. Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy and Depressive Symptoms: The association revisited. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(10):2378–2383. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136–154. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen TS, Backonja MM, Jiménez SH, Tesfaye S, Valensi P, Ziegler D. New perspectives on the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3(2):108–119. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovaguimian A, Gibbons CH. Clinical Approach to the Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2011;2(1):27–38. doi: 10.1177/2042018810391900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang L, Jaiswal M, Martin C, Pop-Busui R. Glucose Control and Diabetic Neuropathy: Lessons from Recent Large Clinical Trials. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(9):528. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0528-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnerup NB, Kuner R, Jensen TS. Neuropathic Pain: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(1):259–301. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S, Chang MC. Effect of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Pain Management: A Systematic Narrative Review. Front Neurol. 2020;11. Accessed December 7, 2022. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin T, Gargya A, Singh H, Sivanesan E, Gulati A. Mechanism of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation in Chronic Pain. Pain Med Off J Am Acad Pain Med. 2020;21(Suppl 1):S6–S12. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Struppler A, Binkofski F, Angerer B, et al. A fronto-parietal network is mediating improvement of motor function related to repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation: A PET-H2O15 study. NeuroImage. 2007;36 Suppl 2:T174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhola R, Kinsella E, Giffin N, et al. Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (sTMS) for the acute treatment of migraine: evaluation of outcome data for the UK post market pilot program. J Headache Pain. 2015;16. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0535-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nizard J, Lefaucheur JP, Helbert M, Chauvigny E de, Nguyen JP. Non-invasive Stimulation Therapies for the Treatment of Refractory Pain. Discov Med. 2012;14(74):21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagnato GL, Miceli G, Marino N, Sciortino D, Bagnato GF. Pulsed electromagnetic fields in knee osteoarthritis: a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2016;55(4):755–762. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefaucheur JP, Aleman A, Baeken C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014–2018). Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(2):474–528. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onesti E, Gabriele M, Cambieri C, et al. H-coil repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for pain relief in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(9):1347–1356. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdelkader AA, El Gohary AM, Mourad HS, El Salmawy DA. Repetitive TMS in treatment of resistant diabetic neuropathic pain. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2019;55(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s41983-019-0075-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weintraub MI, Wolfe GI, Barohn RA, et al. Static magnetic field therapy for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(5):736–746. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wróbel MP, Szymborska-Kajanek A, Wystrychowski G, et al. Impact of low frequency pulsed magnetic fields on pain intensity, quality of life and sleep disturbances in patients with painful diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34(4, Part 1):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weintraub MI, Herrmann DN, Smith AG, Backonja MM, Cole SP. Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields to Reduce Diabetic Neuropathic Pain and Stimulate Neuronal Repair: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(7):1102–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musaev AV, Guseinova SG, Imamverdieva SS. The Use of Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields with Complex Modulation in the Treatment of Patients with Diabetic Polyneuropathy. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2003;33(8):745–752. doi: 10.1023/A:1025184912494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federal Register, Volume 79 Issue 130 (Tuesday, July 8, 2014). Accessed March 14, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2014-07-08/html/2014-15876.htm [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao VP, Satyarengga M, Lamos EM, Munir KM. The Use of Transcutaneous Magnetic Stimulation to Treat Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15(6):1406–1407. doi: 10.1177/19322968211026943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argoff CE, Cole BE, Fishbain DA, Irving GA. Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: Clinical and Quality-of-Life Issues. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(4, Supplement):S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61474-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benbow SJ, Wallymahmed ME, MacFarlane IA. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy and quality of life. QJM Int J Med. 1998;91(11):733–737. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.11.733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boucek P Advanced Diabetic Neuropathy: A Point of no Return? Rev Diabet Stud. 2006;3(3):143–150. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2006.3.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sloan G, Selvarajah D, Tesfaye S. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management of diabetic sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(7):400–420. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00496-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.