Abstract

There is an ongoing unmet need of early identification and discussion regarding the sexual and urinary dysfunction in the peri-operative period to improve the quality of life (QoL), particularly in young rectal cancer survivors. Retrospective analysis of prospectively maintained database was done. Male patients less than 60 years who underwent nerve preserving, sphincter sparing rectal cancer surgery between January 2013 and December 2019, were screened. International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) questionnaire was given to assess erectile dysfunction (ED). Patients were asked questions regarding their sexual and urinary function from the EORTC-QL CRC 38 questionnaire, and responses were recorded. Patients were also asked to report any retrograde ejaculation in post-operative period. Sixty-two patients were included in the study. Fifty-four patients (87.1%) received a diversion stoma. Sixteen patients (29.6%) felt stoma was interfering with their sexual function. Six patients (9.7%) reported retrograde ejaculation. Only 5 patients (8.06%) had moderate to severe ED, and the rest had none to mild ED. On univariate and multivariate analysis, only age predicted the development of clinically significant ED. Ten patients (16.1%) had significantly reduced sexual urges, and 23 patients (37.1%) had significant decrease in sexual satisfaction after surgery. Five patients (8.06%) reported having minor urinary complaints. No patient reported having major complaint pertaining to urinary health. While long-term urinary complaints are infrequent, almost half the patient suffered from erectile dysfunction in some form. There is a weak but significant association of age and ED. Follow-up clinic visits provide an ideal opportunity to counsel patients and provide any medical intervention, when necessary.

Keywords: Nerve sparing surgery, Rectal cancer, Functional outcomes, Erectile dysfunction

Background

Over the last two decades, survival statistics in rectal cancer have reached a plateau with continued improvement in the neoadjuvant treatment, MRI-based staging, and enhanced understanding of planes of rectal surgery. The 5-year overall survival in locally advanced cancers is around 75% with a distant metastases rate as low as 7.5% at 5 years [1] [2] [3]. There is a growing focus on survivorship issues, with an aim to reducing the treatment related toxicity and ensuring superior functional outcomes [4] [5]. Sexual and urinary dysfunction comprises the chief long-term treatment related sequelae because of close proximity of the autonomic nervous system with the pelvic viscera within narrow confines of the bony pelvis [6] [7] [8]. Early identification of sexual and urinary dysfunctions and discussion with patient regarding their incidence and management is now considered a necessary part of the effort to improve QoL outcomes especially among young rectal cancer survivors. In this study, we analyze the incidence and prevalence of sexual and urinary dysfunctions following surgery for rectal cancer in a developing country with a younger median age of incidence.

Aim

To analyze the patient reported outcomes with regard to urinary and sexual dysfunction following surgery for rectal adenocarcinoma.

Material and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of the prospectively maintained database in Colorectal Division, Department of GI and HPB Surgery at Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai. A cross-sectional study design was adopted, surveying the eligible patients presenting in follow-up OPD. Patients who underwent rectal cancer surgery between January 2013 and December 2019 were screened. Patients satisfying the criteria listed below were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria:

Male patients less than 60 years of age who underwent treatment for rectal adenocarcinoma

Patients undergoing standard TME

Patients who underwent sphincter preserving surgery

Patients who had preservation of autonomic nerves as per operative notes

Exclusion criteria:

Patients who underwent extended (eTME) or beyond total mesorectal excision (bTME)

Patients who received permanent stoma

Patients who developed clinically significant anastomotic leak.

Patients who underwent cytoreductive surgery with or without intra-peritoneal chemotherapy

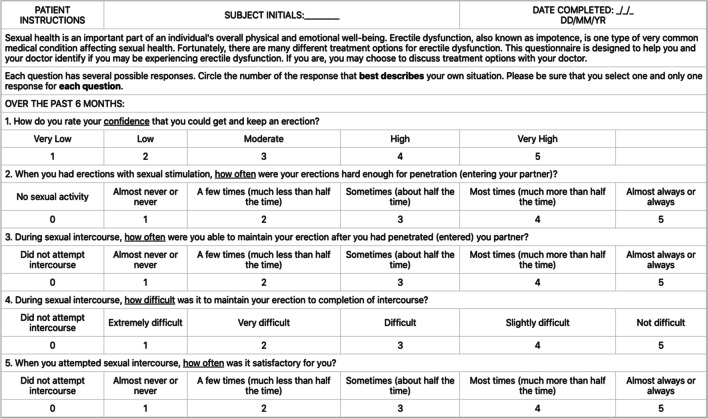

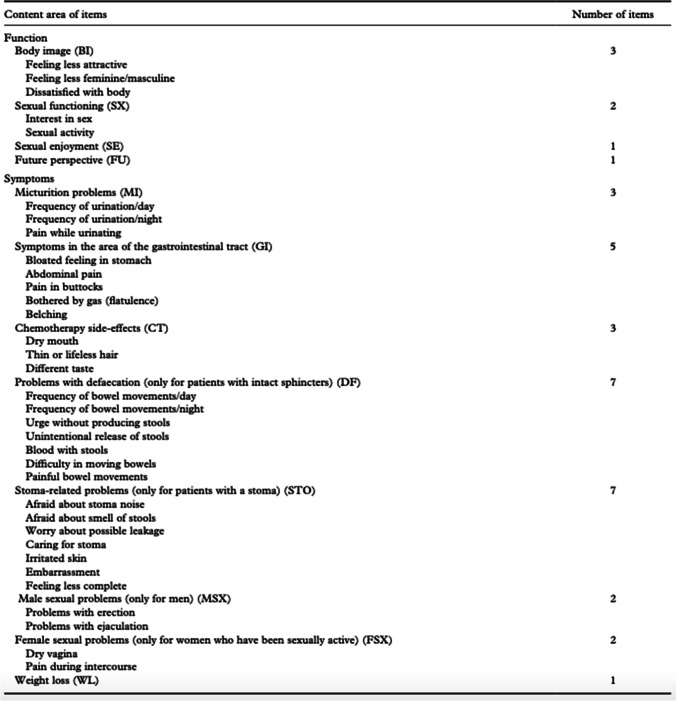

Eligible patients were presented with study questionnaire on their scheduled follow-up visit to the OPD. These were administered at least 6 months after ostomy reversal to be able to assess the impact of temporary ostomy on the functional well-being. Also, they were administered at least 1 year after completion of oncological treatment (surgery-radiation-chemotherapy) to rule out very early recurrence and allow time for stabilization of acute treatment-related changes. Appropriate informed consent from the patients was obtained to permit the use of the information for the study. The study questionnaire included queries from the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) pertaining to assessment of erectile dysfunction (ED) [9] [10] [Fig. 1] as well as the EORTC QLQ-CR38 questionnaire[Fig. 2] focusing on the sexual and urinary health in patients of colo-rectal cancer (CRC). In addition, the study questionnaire included questions discussing retrograde ejaculation and impact of the diversion stoma on the sexual life. The compiled study questionnaire can be found in the supplement. The questionnaire was presented by a doctor who was blinded to the operative details, in the follow-up clinic. Appropriate on-spot translation of the questionnaire to the regional dialect of the patient was done by the concerned doctor.

Fig. 1.

Abridged 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5)

Fig. 2.

EORTC QLQ CR-38 questionnaire

Treatment Protocol

All patients are discussed in a multi-disciplinary joint clinic prior to treatment initiation. Patients with locally advanced rectal cancers receive either neoadjuvant long-course chemoradiation (50.4 Gy external beam radiation with concurrent capecitabine) or short course radiation therapy (25 Gy in 5 fractions) with or without chemotherapy followed by a delayed surgery between 6 and 8 weeks. The technique of nerve preservation during the conduct of a standard TME rectal cancer surgery has been published by the authors [11].

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS (version 25) software. Student t-test was used for nominal data, while Chi square test used for comparing continuous variables. Informed consent was obtained, and procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional or regional) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983.

Results

Sixty-two patients who were eligible and who responded to the questionnaires were included in the study. The mean age of the cohort was 44 years (range 24–60 years). Fifty-seven patients (91.9%) were married, and 56 (90.3%) had at least one child, prior to starting treatment for rectal cancer. The mean body mass index of the cohort was 23.8 kg/m2. Analyzing the comorbidity profile of patients, 50 patients (80.6%) had no known comorbidities, while 12 patients (19.4%) had either diabetes or hypertension or both.

The mean duration between the surgery for primary tumor and the interview was 29.5 months (12–110 months). The mean duration between the date of reversal of diversion stoma and the interview was 11.6 months (range 7–45 months).

The mean distance of tumor from the anal verge was 6 cm (range 1–20 cm). Fifty-one patients (82.3%) received neoadjuvant radiation therapy with median duration between the end of radiation therapy to the surgery being 7 weeks. The surgical procedures performed were anterior resection in 12 patients (19.4%), low anterior resection in 30 patients (48.4%), and inter-sphincteric resections in 20 patients (32.3%). Of these, 54 patients (87.1%) received a diversion stoma. Majority of the surgeries (98.4%) were performed using minimally invasive approach.

Analysis of Response of Questionnaire

-

A.

Sexual Dysfunction

Based on calculated SHIM score from IIEF-5 questionnaire, only 5 patients (8.06%) had moderate to severe ED, and the rest had none to mild ED only. Patients were divided on basis of reporting of clinically significant ED (SHIM score 1–16) or clinically non-significant ED (SHIM score >/16), and baseline characteristics such as age, presence of comorbidities, BMI, distance of tumor from anal verge, neoadjuvant radiation therapy, and surgical procedure as well as approach were noted (Table 1). The distribution of the SHIM scores is shown in Table 2.

Patients with clinically significant ED were likely to be older. On univariate analysis, age was found to be significant predictor of clinically significant ED (OR 1.072 (95% CI 1.008–1.139); p value 0.026). Even on multivariate analysis, patient age alone predicted the development of clinically significant ED (OR 1.074 (95% CI: 1.008–1.145); p 0.028). There is a weak but significant association of age and development of erectile dysfunction in post-operative period in our study (Table 3)

Table 1.

Distribution of baseline characteristics between groups of patients with and without clinically significant erectile dysfunction (ED)

| Clinically significant ED(n=20) | Not significant ED(n=20) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46 yeasrs | 42 years | 0.028 | |

| Comorbidities | 30% | 14.3% | 0.143 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.35 | 23.75 | 0.316 | |

| Distance from AV | 5cm | 6cm | 0.152 | |

| Peoperative RT | 85% | 81% | 0.698 | |

| Surgical procedure | AR | 5% | 26.2% | 0.33 |

| LAR | 60% | 42.9% | ||

| ISR | 35% | 31% | ||

| Surgical Approach | Open | 0 | 2.4% | 0.757 |

| Laparoscopic | 75% | 76.2% | ||

| Robotic | 25% | 21.4% | ||

Table 3.

Distribution of SHIM scores based on IIEF-5 questionnaire

| Degree of dysfunction (SHIM score) | Number of patients | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| No ED [22–25] | 29 | 46.8 |

| Mild ED [17–21] | 13 | 21.0 |

| Mild–moderate ED [12–16] | 15 | 24.2 |

| Moderate ED [8–11] | 3 | 4.8 |

| Severe ED [1–7] | 2 | 3.2 |

| Total | 62 | 100.0 |

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for factors influencing clinically significant erectile dysfunction

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Age | 1.072 | 1.008–1.139 | 0.026 | 1.074 | 1.008–1.145 | 0.028 | |

| BMI | 1.055 | 0.918–1.212 | 0.453 | ||||

| Distance from AV | 0.893 | 0.761–1.048 | 0.165 | ||||

| Preoperative radiation | 1.333 | 0.313–5.679 | 0.697 | ||||

| Surgery | AR | Reference | Reference | ||||

| LAR | 7.333 | 0.834–64.454 | 0.073 | 7.017 | 0.765–64.396 | 0.084 | |

| ISR | 5.923 | 0.628–55.853 | 0.120 | 7.549 | 0.748–76.212 | 0.086 | |

| Surgical approach | Lap | Reference | |||||

| Robotic | 1.185 | 0.338–4.151 | 0.790 | ||||

Based on a odds ratio calculations, the predicted value for significant ED from given dataset increases from 15% chance at age 30 up to 72.6% chance at age 70 ( Table 4).

Table 4.

Predicted value of clinically significant ED in given dataset (based on odds ratio calculation)

| Patient age (years) | Chance of ED |

|---|---|

| 30 | 15% |

| 40 | 25% |

| 50 | 40% |

| 60 | 57% |

| 70 | 72.6% |

Six patients (9.1%) reported retrograde ejaculation, while 3 (4.8%) patients reported painful ejaculation. Sixteen patients (29.6%) felt stoma was interfering with their sexual function. Among them, 12 patients (19.4%) never attempted sexual intercourse after the index surgery. Six of them reported similar or increased sexual desire, while the remaining 6 reported significant decrease in desire. As per the questions on sexual function from the EORTC QLQ CR-38 questionnaire, 10 patients (16.1%) had significantly reduced sexual urges, and 23 patients (37.1%) had significant decrease in sexual satisfaction after surgery.

-

2

Urinary Dysfunction

Within 30 days of surgery, 10 patients (16.13%) reported urinary incontinence, and 14 patients reported (22.58%) increased urinary frequency. Most patients reported self-improvement with time. Beyond 30 days after surgery, only 3 patients (4.8%) complained of persistent urinary incontinence, and 4 patients (6.4%) had increased urinary frequency particularly at night. Overall, 5 patients (8.06%) reported having minor urinary complaints. No patient reported having major complaint pertaining to urinary health.

Discussion

Significant breakthroughs in treatment protocols for management of adenocarcinoma of rectum have led to a substantial improvement in survival outcomes. Patient reported outcome measures assessing quality of life parameters pertaining to sexual and urinary health have gained importance while evaluating and reporting post-operative outcomes [12] [13].

Functional problems are quite common, multi-factorial, often ignored or left untreated and under-reported, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The rate of uro-genital dysfunction ranges from 30 to 70%. This is attributed to both effects of radiotherapy and surgical dissection [14] [15] [16] [17]. Reports from developing nations have shown that nearly 77% of cases of colorectal malignancies are less than 60 years old, 44% cases in age group of 40–60 years, and 33% below the age of 40 years [18]. Given this preponderance of CRC in young patient population, optimization of sexual and urinary function is a highly desired outcome.

Control of sexual and urinary function is governed by a delicate balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic nervous system. Definitive treatment of rectal cancer is known to put these autonomic nerves at risk of damage within the close confines of the pelvic cavity [7]. Dysfunction can occur following a direct injury to either superior hypogastric nerves or the inferior hypogastric nerve plexus or following vascular damage to the vasa nervosa. These structures are prone to injury by traction, devascularization, or thermal damage [19] [6].

Surgical technique of nerve preservation during rectal cancer surgery can help improve the rates of functional preservation [11] [20]. These techniques, however, may not be applicable in every patient. Both open and minimally invasive surgical approach have shown equivocal results with respect to functional outcomes [21] [22]. On a similar note, no clinically relevant difference has been seen between laparoscopic and robotic platforms [23]. Functional disturbances are reported to increase after pelvic radiotherapy RT to pelvic organs, and it may have both short-term and long-term sequalae [24] [25].

Clinicians often face questions regarding the survivorship issues in follow-up outpatient clinic. These hospital visits in the peri-operative period and even after treatment completion provide an opportunity to address and respond to such queries with a correct knowledge-attitude-practice schema [26]. Discussion on sexual health with the patients along with reassurance can often help patients overcome self-imposed restrictions on sexual life, especially patients with an ostomy [27]. In the current study, 16 patients (29.6%) reported the temporary stoma to be interfering with the sexual functions. Twelve patients (19.4%) out of these 16 never attempted sexual intercourse post-surgery, 6 of whom reported a normal libido. Authors excluded patients with permanent ostomy from the study to provide an opportunity to assess and highlight the stigmata and impact of temporary stoma on the sexual health, prior to ostomy reversal. Patients with permanent ostomy form an entirely different problem statement in a diverse country like India with many social and functional limitations. It is challenging to record these issues with the currently validated Western questionnaires.

Pre-operative counselling regarding possible sexual and urinary dysfunction in post-operative period was done in all patients but in high volume centers in low–middle-income countries though keeping record of counselling in high volume centers in LMICs is not always possible. Discussion regarding the sexual outcomes should begin at treatment initiation and continue during the course of treatment [28]. Often, patients report urogenital dysfunction even prior to the surgery, drawing attention to need of discussion in the pre-operative period regarding patient expectations in the peri-operative period [29]. Published data suggests this is often ignored or underplayed while discussing the management of disease with patient [30] [31].

Anatomically, there are four key areas where the nerves are at a higher risk of injury during surgery.

-

A)

Dissection and ligation of inferior mesenteric artery flush to the aorta causes injury to the superior hypogastric plexus.

-

B)

The sympathetic hypogastric nerves may be damaged while doing the posterior pelvic dissection. These nerves lie just outside the “Holy Plane of Heald”.

-

C)

Lateral dissection may injure the inferior hypogastric nerve plexus, especially associated with excess traction during surgery. Injury to sympathetic system is mainly associated with problems in ejaculation.

-

D)

Injury to the cavernous nerves during the anterior dissection of the rectum away from prostate and seminal vesicles can damage the parasympathetic nerves, being more often associated with impotence. Patients undergoing APR for low rectal cancer require manipulation and disruption of these nerves. Hence, those undergoing this procedure were excluded.

In the current study, only 5 patients (8%) had moderate to severe ED, while 6 patients (9.1%) reported retrograde ejaculation. Age alone was found to be a predictor of clinically significant erectile dysfunction (SHIM score International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) pertaining to assessment of erectile dysfunction (ED) [9] [10] [Fig. 1] </16)

Urinary dysfunction depends on the site of damage to pelvic autonomic nervous system. Patients may develop reduced bladder capacity with urge incontinence or overdistension of bladder with overflow incontinence or difficulty in bladder emptying with urinary retention. Normally, the sympathetic system is associated with retention of urine caused by contraction of the smooth muscles in trigone and urethra which co-ordinates with contraction of external urethral sphincter. It stays activated until bladder pressure triggers a micturition reflex. Parasympathetic system triggers voiding by causing detrusor contraction, relaxation of urethra, and coordinated inhibition of external urethral sphincter. While temporary dysfunction of urinary function may be common, long-term dysfunction requires significant damage (usually bilaterally) to autonomic nerves. In the current study, 22.58% patients reported urinary dysfunction within 30 days of surgery. Beyond the 30-day period, only 8.06% reported having minor urinary complaints. No patient reported having major complaint pertaining to the urinary health.

Early identification of the problem provides an opportunity for timely intervention. In our set up, patients with erectile dysfunction in the post-operative period are referred to an andrologist and those with urinary dysfunctions to urologist for further investigations and management following appropriate discussion regarding expectations [32]. Patients troubled with refractory and persistent long-term urinary and sexual complaints can be candidates for experimental treatment options like post-operative sacral neuromodulation [33] [34].

Strengths of study lie in the fact of it being a single-center experience in the modern era of management which ensures uniform up-to-date treatment practice across all patients. It is the first report on the subject coming from a tertiary care center in a developing nation where health infrastructure is often inadequate to cater to QoL and survivorship issues. The overall rate of erectile dysfunction was 53.2% along with a very low long-term urinary dysfunction, which is comparable with available literature from other high volume centers.

Drawbacks of the study include a retrospective analysis in a small cohort of patients. The sexual and urinary function of patients at baseline prior to initiation of treatment is not available. Objective comparison with the pre-operative sexual and urinary functions would add more meaning to the results. Patients analyzed here were included based on the operative notes which suggested preservation of the hypogastric nerves. It would be better in future studies to have an accountability of integrity of inferior hypogastric nerve plexus.

In summary, almost 25% of the patients’ attribute ostomy to interfere with sexual life while one in five never resumes their sexual function. Almost half the patient suffered from erectile dysfunction in some form. Persistent long-term urinary complaints are infrequent

The authors look forward to the results from larger prospective studies like the PROCaRe study, a multi-center prospective observational study to shed further light on this subject [35].

Conclusion

Our analysis revealed increasing age as a predictor of significant erectile dysfunction among patients undergoing sphincter saving surgery for rectal cancer

This snapshot audit reveals good outcomes in terms of urinary and sexual dysfunction after minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancers. There are lacunae in system with regard to optimal counselling in patients’ post-surgery. A specialist nurse to monitor outcomes in survivorship program and to refer to specialist as needed is recommended.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of the study are available upon request from the authors.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EM-K, Putter H, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):575–582. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Putter H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):638–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CAM, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM-K, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;1:29–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li K, He X, Tong S, Zheng Y. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery in 948 consecutive patients: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(8):2087–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.03.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attaallah W, Ertekin C, Tinay I, Yegen C. High rate of sexual dysfunction following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2014;30(5):210. doi: 10.3393/ac.2014.30.5.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moszkowicz D, Alsaid B, Bessede T, Penna C, Nordlinger B, Benoît G, et al. Where does pelvic nerve injury occur during rectal surgery for cancer?: pelvic nerve injury during rectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(12):1326–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsey I, Guy RJ, Warren BF, Mortensen NJMcC. Anatomy of Denonvilliers’ fascia and pelvic nerves, impotence, and implications for the colorectal surgeon: Denonvilliers’ fascia and impotence after rectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2000;87(10):1288–1299. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baader B, Herrmann M. Topography of the pelvic autonomic nervous system and its potential impact on surgical intervention in the pelvis. Clin Anat. 2003;16(2):119–130. doi: 10.1002/ca.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sprangers MAG, te Velde A, Aaronson NK. The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38) Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(2):238–247. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen R, Cappelleri J, Smith M, Lipsky J, Peña B. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the international index of erectile function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11(6):319–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel S, Sukumar V, Kazi M, Mohan A, Bankar S, Desouza AL, et al. Nerve sparing Laparoscopic Low anterior rectal resection – a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2021;codi:15648. doi: 10.1111/codi.15648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besson A, Deftereos I, Chan S, Faragher IG, Kinsella R, Yeung JM. Understanding patient-reported outcome measures in colorectal cancer. Future Oncol. 2019;15(10):1135–1146. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins AT, Rothman RL, Geiger TM, Canedo JR, Edwards-Hollingsworth K, LaNeve DC, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in colon and rectal surgery: a systematic review and quality assessment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(8):1156–1167. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriya Y. Function preservation in rectal cancer surgery. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11(5):339–343. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0608-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack J, Holm T, Cedermark B, Altman D, Holmström B, Glimelius B, et al. Late adverse effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93(12):1519–1525. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junginger T, Kneist W, Heintz A. Influence of identification and preservation of pelvic autonomic nerves in rectal cancer surgery on bladder dysfunction after total mesorectal excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(5):621–628. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange MM, Maas CP, Marijnen CAM, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, Kranenbarg EK, et al. Urinary dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment is mainly caused by surgery. Br J Surg. 2008;95(8):1020–1028. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patil PS, Saklani A, Gambhire P, Mehta S, Engineer R, De’Souza A, et al. Colorectal cancer in India: an audit from a tertiary center in a low prevalence area. Indian. J Surg Oncol. 2017;8(4):484–490. doi: 10.1007/s13193-017-0655-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bissett I, Zarkovic A, Hamilton P, Al-Ali S. Localisation of hypogastric nerves and pelvic plexus in relation to rectal cancer surgery. Eur J Anat. 2007;8:111. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celentano V, Fabbrocile G, Luglio G, Antonelli G, Tarquini R, Bucci L. Prospective study of sexual dysfunction in men with rectal cancer: feasibility and results of nerve sparing surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(12):1441–1445. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0995-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vennix S, Pelzers L, Bouvy N, Beets GL, Pierie J-P, Wiggers T, et al. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2014 Apr 15 [cited 2021 Aug 19]; Available from: https://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD005200.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Jayne DG, Brown JM, Thorpe H, Walker J, Quirke P, Guillou PJ. Bladder and sexual function following resection for rectal cancer in a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open technique. Br J Surg. 2005;92(9):1124–1132. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Annibale A, Pernazza G, Monsellato I, Pende V, Lucandri G, Mazzocchi P, et al. Total mesorectal excision: a comparison of oncological and functional outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(6):1887–1895. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Contin P, Kulu Y, Bruckner T, Sturm M, Welsch T, Müller-Stich BP, et al. Comparative analysis of late functional outcome following preoperative radiation therapy or chemoradiotherapy and surgery or surgery alone in rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(2):165–175. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1780-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiltink LM, Chen TYT, Nout RA, Kranenbarg EM-K, Fiocco M, Laurberg S, et al. Health-related quality of life 14years after preoperative short-term radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(14):2390–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sibert NT, Kowalski C, Pfaff H, Wesselmann S, Breidenbach C. Clinicians’ knowledge and attitudes towards patient reported outcomes in colorectal cancer care – insights from qualitative interviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):366. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06361-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.García-Rodríguez MT, Barreiro-Trillo A, Seijo-Bestilleiro R, González-Martin C. Sexual dysfunction in ostomized patients: a systematized review. Healthcare. 2021;9(5):520. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva GM, Hull T, Roberts PL, Ruiz DE, Wexner SD, Weiss EG, et al. The effect of colorectal surgery in female sexual function, body image, self-esteem and general health: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2008;248(2):266–272. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181820cf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dulskas A, Samalavicius NE. A prospective study of sexual and urinary function before and after total mesorectal excision. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(6):1125–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2549-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanoff H, Morris W, Mitcheltree A-L, Wilson S, Lund J. Lack of support and information regarding long-term negative effects in survivors of rectal cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):444–448. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.444-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leon-Carlyle M, Schmocker S, Victor JC, Maier B-A, O’Connor BI, Baxter NN, et al. Prevalence of physiologic sexual dysfunction is high following treatment for rectal cancer: but is it the only thing that matters? Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(8):736–742. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Notarnicola M, Celentano V, Gavriilidis P, Abdi B, Beghdadi N, Sommacale D, et al. PDE-5i management of erectile dysfunction after rectal surgery: a systematic review focusing on treatment efficacy. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14(5):155798832096906. doi: 10.1177/1557988320969061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nocera F, Angehrn F, von Flüe M, Steinemann DC. Optimising functional outcomes in rectal cancer surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406(2):233–250. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-01937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbera L, Zwaal C, Elterman D, McPherson K, Wolfman W, Katz A, et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(3):192–200. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patient reported outcomes following cancer of the rectum (PROCaRe). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04936581 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of the study are available upon request from the authors.