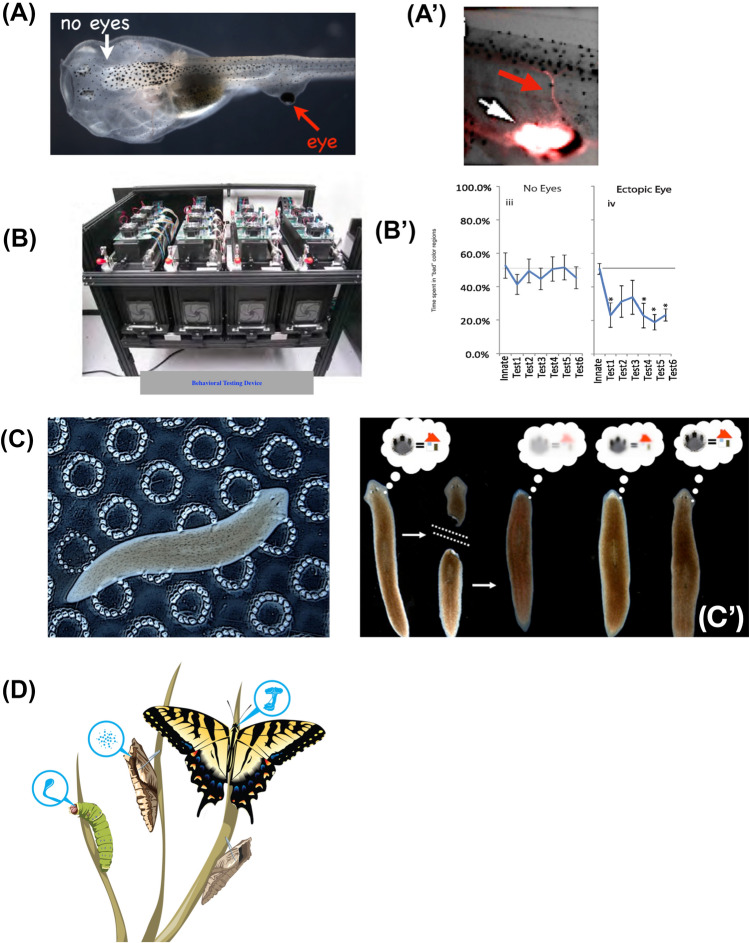

Fig. 3.

Unconventional agents: plasticity and robustness to change. A Tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis can be made to have no primary eyes (white arrow), but instead have an ectopic eye on its tail (red arrow). A’ These ectopic eyes (white arrow) can connect to the spinal cord (red arrow). B Using an automated behavioral training and testing apparatus, these animals can be shown to be able to see out of those eyes in a color vision training assay (B’) despite a novel visual system architecture that had no evolutionary adaptation—a remarkable example of functional plasticity despite wild-type genetics. C Planarian flatworms can be trained to associate laser-etched circular regions (bumps) in a petri dish surface with food. When their heads are amputated (C’), their behavior shows recall of the original information (place conditioning), showing the ability of memory to be stored outside the head and imprinted on newly produced brain tissue (showing how functional, behavioral memories are dynamically integrated with the tissue-level patterning processes that create specific shapes in anatomical morphospace). D Caterpillars (and other insect larvae) metamorphose into very different forms, which requires extensive disassembly and rebuilding of the brain. Despite this, their memories persist, showing that individual agents change during their lifetime not only due to experiences and learning, but also can radically change with respect to anatomical structure. Panel D created by Jeremy Guay of Peregrine Creative. Panels A–C used by permission from (Blackiston et al. 2010; Blackiston and Levin 2013; Levin 2022; Shomrat and Levin 2013); C’,D used by permission from (Levin 2022). (color figure online)