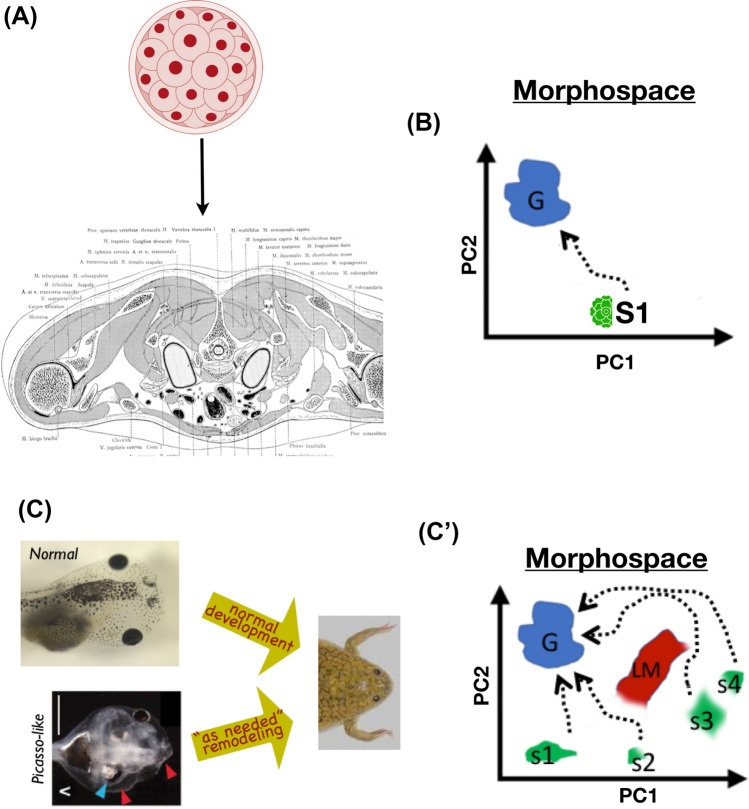

Fig. 7.

Morphogenesis as competent behavioral navigation. A Animals begin life as a single cell and then a ball of embryonic blastomeres, which eventually gives rise to the incredible complexity of the body (cross section of the human torso is shown here). B Viewing anatomical structure as a morphospace of parameters describing possible configurations (here simplified to 2 dimensions, principal components (PC) 1 and 2), one can imagine this process as a hardwired transition from a starting state (S1) to an ensemble of states corresponding to viable adult organisms (goal states G). C However, when probed by perturbation (as any novel animal’s behavior is studied), traversals of morphospace are revealed to exhibit considerable flexibility. Here is shown an example of metamorphosis in the frog Xenopus laevis. Not only do normal tadpoles (starting from a standard, correct state) become frogs by rearranging the components of their face, but so do “Picasso tadpoles” in which all the organ positions have been scrambled. This is because the organs then move in novel paths and different distances, as needed, to achieve a normal frog craniofacial morphology, thus showing the capacity (C’) to move to the right region of morphospace from diverse starting positions (S1–S4) and despite various obstacles (local minima LM, in which less competent navigational agents would get stuck). Panels A,B,C’ by Jeremy Guay of Peregrine Creative; C courtesy of Douglas Blackiston and Erin Switzer, and taken with permission from (Vandenberg et al. 2011)