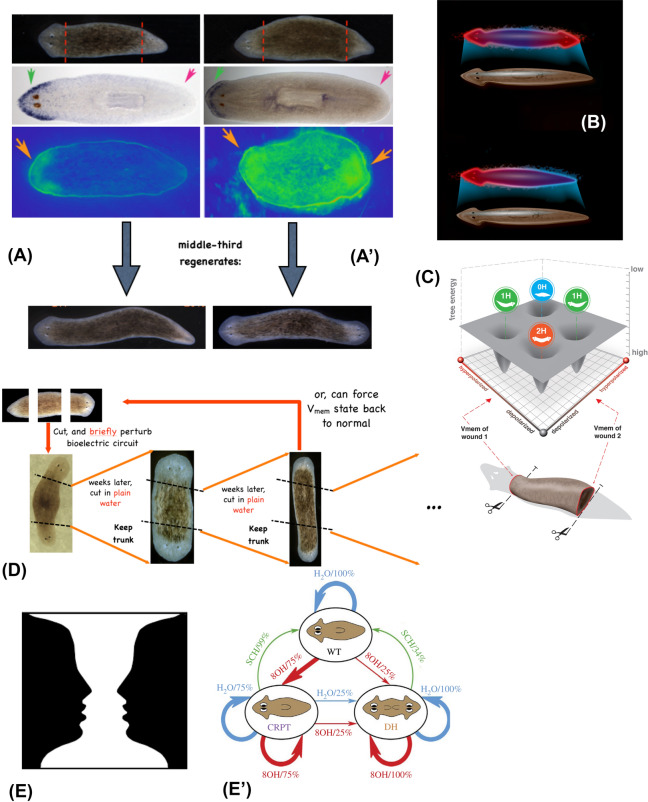

Fig. 9.

Morphogenetic memory can be re-written non-genetically. A Normal planaria (left column) exhibit anterior gene expression in the head, and when cut into three fragments, produce normal one-headed worms. In contrast (A’), planaria in which the normal bioelectric pattern has been re-written by brief pharmacological targeting of ion channels (blue panels, green indicates depolarized regions on the voltage map) give rise to two-headed animals. Note that the bioelectrical map shown is a map of the animal pre-cutting. B Thus, a normal planarian body can store one of 2 (at least) representations of what a correct planarian should look like. Much as in the nervous system, somatic bioelectricity enables changes in how systems navigate morphospace based on experience, not only genetic rewiring. C Bioelectric circuit dynamics enable the planarian fragments to navigate a morphospace which contains attractors for 0, 1, or 2 heads as the target state which each fragment seeks to achieve. D Ability to reliably reach the right morphogenetic state is indeed a kind of memory which is stable but re-writable. Two-headed animals continue to give rise to two-headed animals upon further rounds of amputation (deviation into an incorrect region of morphospace), without changing the genetics of the cells. The two-headed state can be reversed by the same kind of technique, targeting ion flux to re-set the target morphology representation back to a one-headed configuration. E Kind of perceptual bistability seen in ambiguous images (such as this famous “2 faces vs. vase” example) is also seen in morphogenetic systems: so-called Cryptic Worms have a destabilized target morphology memory, producing stochastically one-head or two-head forms upon each round of cutting. WT wild type, CRPT cryptic state, DH double-head. This ethnogram, applied to morphogenetic experiments, shows the transition probabilities when cut in water (H2O) or octanol (8OH, a gap junction blocker) or SCH28080 (SCH, a proton–potassium exchanger inhibitor). Images in panels B, C are by Jeremy Guay of Peregrine Creative. Others are used with permission from (Durant et al. 2017; Levin 2021a)