Abstract

The prevailing notion that reduced cofactors NADH and FADH2 transfer electrons from the tricarboxylic acid cycle to the mitochondrial electron transfer system creates ambiguities regarding respiratory Complex II (CII). CII is the only membrane-bound enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and is part of the electron transfer system of the mitochondrial inner membrane feeding electrons into the coenzyme Q-junction. The succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHA of CII oxidizes succinate and reduces the covalently bound prosthetic group FAD to FADH2 in the canonical forward tricarboxylic acid cycle. However, several graphical representations of the electron transfer system depict FADH2 in the mitochondrial matrix as a substrate to be oxidized by CII. This leads to the false conclusion that FADH2 from the β-oxidation cycle in fatty acid oxidation feeds electrons into CII. In reality, dehydrogenases of fatty acid oxidation channel electrons to the Q-junction but not through CII. The ambiguities surrounding Complex II in the literature and educational resources call for quality control, to secure scientific standards in current communications of bioenergetics, and ultimately support adequate clinical applications. This review aims to raise awareness of the inherent ambiguity crisis, complementing efforts to address the well-acknowledged issues of credibility and reproducibility.

Keywords: coenzyme Q, Complex II, electron transfer system, fatty acid oxidation, flavin adenine dinucleotide, succinate dehydrogenase, tricarboxylic acid cycle

Current studies on cellular and mitochondrial bioenergetics sparked a new interest in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle also known as the citric acid cycle or Krebs cycle (1, 2, 3, 4). TCA cycle metabolites are oxidized while reducing NAD+ to NADH+H+ in the forward cycle or are transported into the cytosol mainly by passive diffusion dependent on concentration differences across the mitochondrial membranes (5, 6). Respiratory Complex II (CII, succinate dehydrogenase SDH; succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase SQR; EC 1.3.5.1)—discovered in 1909 (7, 8)—has a unique position in both the TCA cycle and the mitochondrial membrane-bound electron transfer system (membrane-ETS). All genes for CII are nuclear-encoded, with exceptions in some red algae and land plants (9, 10). SQRs favor the oxidation of succinate and reduction of quinone in the canonical forward direction of the TCA cycle (11). Operating in the reverse direction, quinol:fumarate reductases (QFRs, fumarate reductases) reduce fumarate and oxidize quinol (12, 13). The reverse TCA cycle has gained interest in studies ranging from metabolism in anaerobic animals (14, 15), thermodynamic efficiency of anaerobic and aerobic ATP production (16), reverse electron transfer and production of reactive oxygen species (17, 18, 19), hypoxia and ischemia-reperfusion injury (20), to evolution of metabolic pathways (21, 22). In cancer tissues, CII plays a key role in metabolic remodeling (23, 24). Beyond its role in electron transfer in the TCA cycle and the membrane-ETS, CII and succinate serve multiple functions in metabolic signaling (25, 26, 27). CII is thus a target of current pharmacological developments (28, 29).

The pyridine derivative NAD+ is reduced to NADH+H+ during the oxidation of pyruvate and through redox reactions catalyzed by TCA cycle dehydrogenases (DH) including isocitrate DH, oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) DH, and malate DH. In turn, NADH+H+ are the substrates in the oxidation reaction catalyzed by Complex I (CI; NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase; EC 1.6.5.3) which is linked to the reduction of the prosthetic group flavin mononucleotide FMN to FMNH2 and regeneration of NAD+. Likewise, the prosthetic group flavin adenine dinucleotide FAD is reduced to FADH2 during the oxidation of succinate by CII (succinate DH). Confusion emerges, however, when NADH and FADH2 are considered as the reduced substrates feeding electrons from the TCA cycle into the “respiratory chain”—rather than NADH and succinate. This “Complex II ambiguity” has deeply penetrated the scientific literature on bioenergetics without sufficient quality control. Therefore, a critical literature survey is needed to ensure scientific standards in communications on bioenergetics. By drawing attention to widespread CII ambiguities, subsequent erroneous portrayal and misinformation are revealed on the position of CII in pathways of energy metabolism, particularly in graphical representations of the mitochondrial electron transfer system.

While ambiguity is linked to relevant issues of reproducibility, it extends to the communications space of terminological and graphical representations of concepts (30). Type 1 ambiguities are the inevitable consequence of conceptual evolution, in the process of which ambiguities are replaced by experimentally and theoretically supported paradigm shifts to clear-cut theorems. In contrast, type 2 ambiguities are traced in publications that reflect merely a disregard and ignorance of established concepts without any attempt to justify the inherent deviations from high-quality science. There are many shades of grey between these types of ambiguity. The Cambridge Dictionary defines ambiguity as “the fact of something having more than one possible meaning and therefore possibly causing confusion” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/ambiguity (retrieved 2023–09–23). This is opposite to “productive ambiguity” (30) used in the sense of various isomorphic or complementary representations, describing a concept from different points of view. The word relates etymologically to “double meaning” and “equivocalness,” from ambi (around, on both sides).

Ambiguities regarding Complex II (CII) emerge on several fronts. First, they arise when portraying FADH2 within the mitochondrial matrix as both a product of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and a substrate of CII. Although misconstrued, this may be seen as an electron transfer from FADH2 in the SDHA subunit of CII to ubiquinone. Second, numerous publications introduce ambiguity through the presentation of incorrect figures, depicting FADH2 instead of succinate as the substrate for CII. Third, this confusion extends to the representation of the reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) in various misconstrued forms, such as FADH or FADH+, or the oxidized form FAD as FAD+. Fourth, when illustrating the oxidation of FADH2, several figures show reactions like FADH2 → FAD + H+ or FADH2 → FAD + 2H+. These hydrogen ions H+ introduce a spectrum of uncertainties and blur the line between ambiguous interpretations and indisputable misinformation. Aiming at an open frame for discussion, the term ambiguity is used here in a collegial manner rather than a punctilious one. Nevertheless, these ambiguities have been a source of confusion even among established authors of specialized research reports, highly cited reviews, and editorials in leading journals. CII ambiguities have led to erroneous conclusions as will be discussed below.

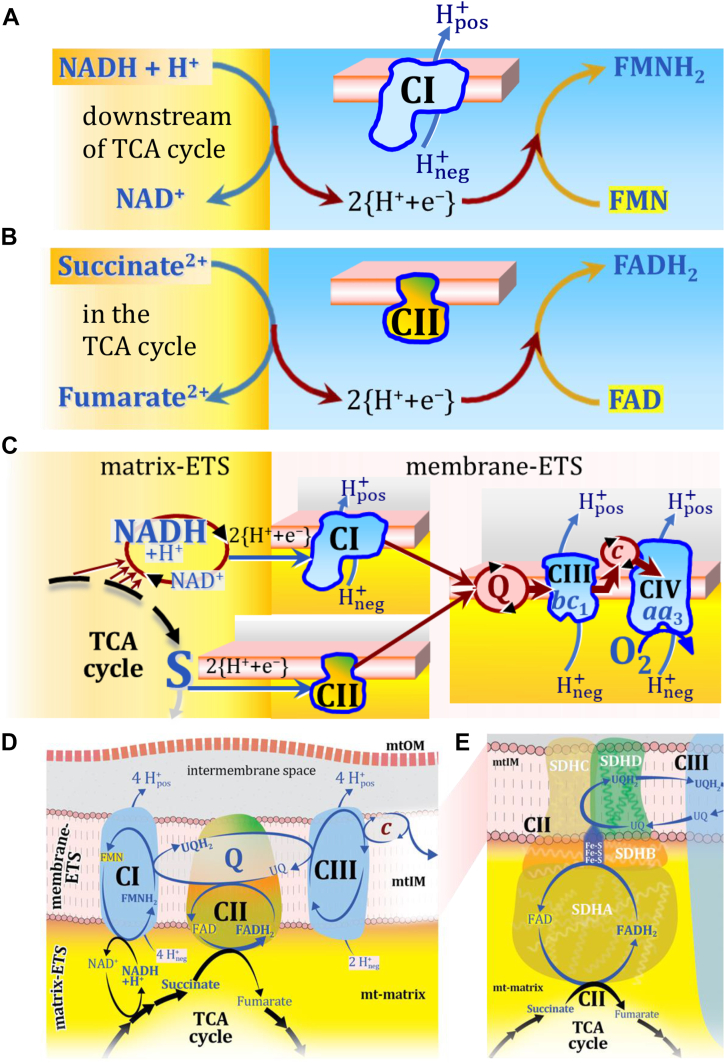

Electron flow through CI and CII to the coenzyme Q junction

The reduced flavin groups FMNH2 of flavin mononucleotide and FADH2 of flavin adenine dinucleotide are at functionally comparable levels in the electron transfer through CI and CII, respectively (Fig. 1, A and B). FMNH2 and FADH2 are reoxidized downstream in CI and CII, respectively, by electron transfer or more explicitly by transfer of 2{H+ + e-} to the ETS-reactive coenzyme Q (Q) (31), reducing ubiquinone (UQ) to ubiquinol (UQH2). The convergent architecture of the electron transfer system (ETS; in contrast to a linear electron transfer chain ETC; a chain's length used to be a linear measure) with multiple branches feeding into the Q-junction is emphasized in Figure 1, C and D (6, 32). Comparable to CII, several respiratory Complexes are localized in the mitochondrial inner membrane (mtIM) which catalyze electron transfer converging at the Q-junction, including electron transferring flavoprotein DH Complex in fatty acid oxidation, glycerophosphate DH Complex, sulfide-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, choline DH, dihydro-orotate DH, and proline DH (3, 6, 32, 33, 34). Electron transfer and corresponding capacities of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are classically studied in mitochondrial preparations as oxygen consumption supported by various fuel substrates undergoing partial oxidation in the mt-matrix, such as pyruvate, malate, succinate, and others (6). Therefore, the matrix component of the ETS (matrix-ETS) is distinguished from the ETS bound to the mtIM (membrane-ETS; Fig. 1C) (2).

Figure 1.

Complex II (SDH) integrates H+-linked electron transfer in the TCA cycle (matrix-ETS) and the electron transfer system (membrane-ETS) of the mt-inner membrane (mtIM). A, NADH+H+ and (B) Succinate are substrates of 2{H+ + e-} transfer to the prosthetic groups FMN and FAD as the corresponding electron acceptors in CI and CII, respectively. C, symbolic representation of ETS pathway architecture. Electron flow converges at the N-junction, NAD++2{H+ + e-} → NADH+H+, and from NADH+H+ and succinate S at the Q-junction, UQ+2{H+ + e-} → UQH2. CIII passes electrons to cytochrome c and in CIV to molecular O2, 2{H+ + e-}+0.5 O2 ⇢ H2O. D, NADH and NAD+ cycle between different matrix-dehydrogenases and CI, whereas FAD and FADH2 remain permanently bound within the same CII-enzyme molecule during the catalytic cycle. Succinate and fumarate indicate the chemical entities irrespective of ionization, whereas charges are shown in NADH (uncharged), NAD+, and H+. Joint pairs of half-circular arrows distinguish the chemical reaction of electron transfer 2{H+ + e-} to CI and CII from vectorial H+ translocation across the mtIM (H+neg → H+pos). CI, CIII, and CIV pump hydrogen ions from the negatively (neg; yellow, mt-matrix) to the positively charged compartment (pos; grey, intermembrane space). E, Iconic representation of SDH subunits. SDHA catalyzes the oxidation succinate → fumarate + 2{H+ + e-} and reduction FAD+2{H+ + e-} → FADH2 in the soluble domain of CII. The iron–sulfur protein SDHB transfers electrons through Fe-S clusters to the mtIM domain where ubiquinone UQ is reduced to ubiquinol UQH2 in SDHC and SDHD.

In most flavin-linked dehydrogenases the flavin adenine nucleotide is a tightly bound prosthetic group. In CII, it is even covalently and thus permanently bound to the enzyme during the catalytic cycle when the redox state is regenerated in each enzymatic turnover, as documented in early reports (35) and summarized in classical textbooks (36, 37). Structural studies of CII have expanded our knowledge of the mechanism of enzyme assembly (13), enzyme structure (38, 39, 40), kinetic regulation of CII activity (41, 42), and associated pathologies (3, 26, 27, 28, 29).

H+-linked two-electron transfer from succinate to flavin adenine dinucleotide reduces the oxidized prosthetic group FAD to FADH2 with formation of fumarate. This H+-linked electron transfer through CII is not coupled to H+ translocation across the mtIM. Hence, CII is not a H+ pump in contrast to the respiratory Complexes CI, CIII, and CIV through which electron transfer—more appropriately 2{H+ + e-} transfer (Table 1)—drives and maintains the protonmotive force.

Table 1.

Three distinct types of transformation with hydrogen ions (hydrons) H+

| Transformation | Equation | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Acid-base equilibrium | H3O+ ↔ H2O + H+ (a) H2CO3 ↔ HCO3- + H+ (b) |

Scalar, chemical, fast |

| 2a. H+-linked electron transfer, oxidation | Malate2- → Oxaloacetate2- + 2{H++e−} (c) Succinate2- → Fumarate2- + 2{H++e−} (d) |

Scalar, chemical, slow |

| 2b. H+-linked electron transfer, reduction | 2{H++e−} + NAD+ → NADH+H+ (e) 2{H++e−} + E-FAD → E-FADH2 (f) |

Scalar, chemical, slow |

| 3. Transport, translocation | pumping: H+neg → H+pos (g) diffusion: H+pos → H+neg (h) |

Vectorial, Compartmental, transmembrane |

The reversible oxidoreduction of dicarboxylate (succinate/fumarate) is catalyzed in the soluble domain of CII extending from the mtIM into the mt-matrix. Succinate donates 2{H+ + e−} to FAD bound to the subunit SDHA which contains the catalytically active dicarboxylate binding site. The oxidized yellow (450 nm) form FAD functions as the hydrogen acceptor from succinate to the reduced internal product FADH2 while fumarate is formed as the oxidized external product in the TCA cycle. FADH2 relays electrons further through a series of iron-sulfur redox centers in SDHB to reduce UQ to UQH2 in the membrane domain harboring SDHC and SDHD (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 39) (Fig. 1E).

Simple arrows (Fig. 1, A–C) or pairs of rounded arrows—an external arrow touching the enzyme and an internal arrow within the enzyme—indicate chemical reactions of H+-linked electron transfer (Fig. 1, D and E). The term H+-coupled electron transfer (43) is replaced by H+-linked electron transfer, to avoid confusion with coupled H+ translocation. Caution is warranted to distinguish three types of transformation with hydrogen ions, for which IUPAC suggests the term ‘hydrons’ (44): (i) Acid-base reactions equilibrate fast without catalyst. (ii) ‘The terms reducing equivalents or electron equivalents are used to refer to electrons and/or hydrogen atoms participating in oxidoreductions’ (36). Redox transfer of hydrogen atoms is slow and depends on a catalyst. The symbol 2{H+ + e−} is introduced to indicate H+-linked electron transfer of two hydrons and two electrons in a redox reaction. (iii) Vectorial H+ transport is either active with translocation through H+ pumps or passive as diffusion driven by the electrochemical pressure difference across cellular compartments (6) (Table 1).

Sources and consequences of Complex II ambiguities

‘No representation is ever perfectly expressive, for if it were it would not be a representation but the thing itself’ (30).

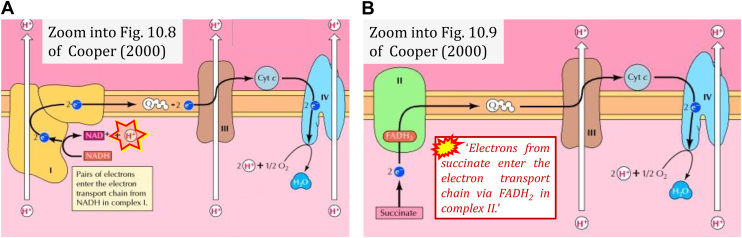

Ambiguities emerge if the representation of a concept is vague to an extent that allows for equivocal interpretations. As a consequence, even a basically clear concept (Fig. 1) may be communicated as a divergence from an established ‘truth’. The comparison between NADH linked to CI and FADH2 (instead of succinate) linked to CII leads us astray, as illustrated by the following textbook quotes (45) which require correction (Fig. 2).

-

(1)

‘Electrons from NADH enter the electron transport chain in complex I, .. A distinct protein complex (complex II), which consists of four polypeptides, receives electrons from the citric acid cycle intermediate, succinate’ (Fig. 2B; ref. (45)). ‘These electrons are transferred to FADH2, rather than to NADH, and then to coenzyme Q.' Note the suggestive comparison of FADH2 and NADH.

-

(2)

‘In contrast to the transfer of electrons from NADH to coenzyme Q at complex I, the transfer of electrons from FADH2 to coenzyme Q is not associated with a significant decrease in free energy and, therefore, is not coupled to ATP synthesis.' Note that CI catalyzes electron transfer from NADH to coenzyme Q. In contrast, electron transfer from FADH2 to coenzyme Q is downstream of succinate oxidation by CII. Thus instead of the Gibbs force (‘decrease in free energy') in FADH2→Q, the total Gibbs force (6) in S→Q must be accounted for. In contrast to the extensive quantity Gibbs energy [J], Gibbs force [J·mol−1] is an intensive quantity expressed as the partial derivative of Gibbs energy [J] per advancement of a reaction [mol] (6, 46). (In parentheses: Redox-driven proton translocation must be distinguished from phosphorylation of ADP driven by the protonmotive force).

-

(3)

‘.. electrons from succinate enter the electron transport chain via FADH2 in complex II.' Note that CII receives electrons from succinate via FAD. The ambiguity is caused by a lack of unequivocal definition of the electron transfer system (‘electron transport chain’). Two contrasting definitions are implied of the “electron transport chain” or ETS. (a) CII is part of the ETS. Hence electrons enter the ETS in the succinate branch from succinate but not from FADH2 – from the matrix-ETS to the membrane-ETS (Fig. 1, C and D). (b) If electrons enter the ‘electron transport chain via FADH2 in complex II', then subunit SDHA would be upstream and hence not part of the ETS (to which conclusion obviously nobody would agree). Electrons enter CII and thus the membrane-ETS from succinate (Fig. 1) but not from FADH2 as the “product” of succinate dehydrogenase in the TCA cycle, as erroneously shown in Figure 3, A and B.

Figure 2.

Electron transfer to CI and CII. Zoom into figures of ref. (45). A, H+ (marked) is shown to be produced in H+-linked electron transfer instead of being consumed (cf. Fig. 1A). B, Marked quote inserted from the legend to Fig. 10.9 of ref. (45).

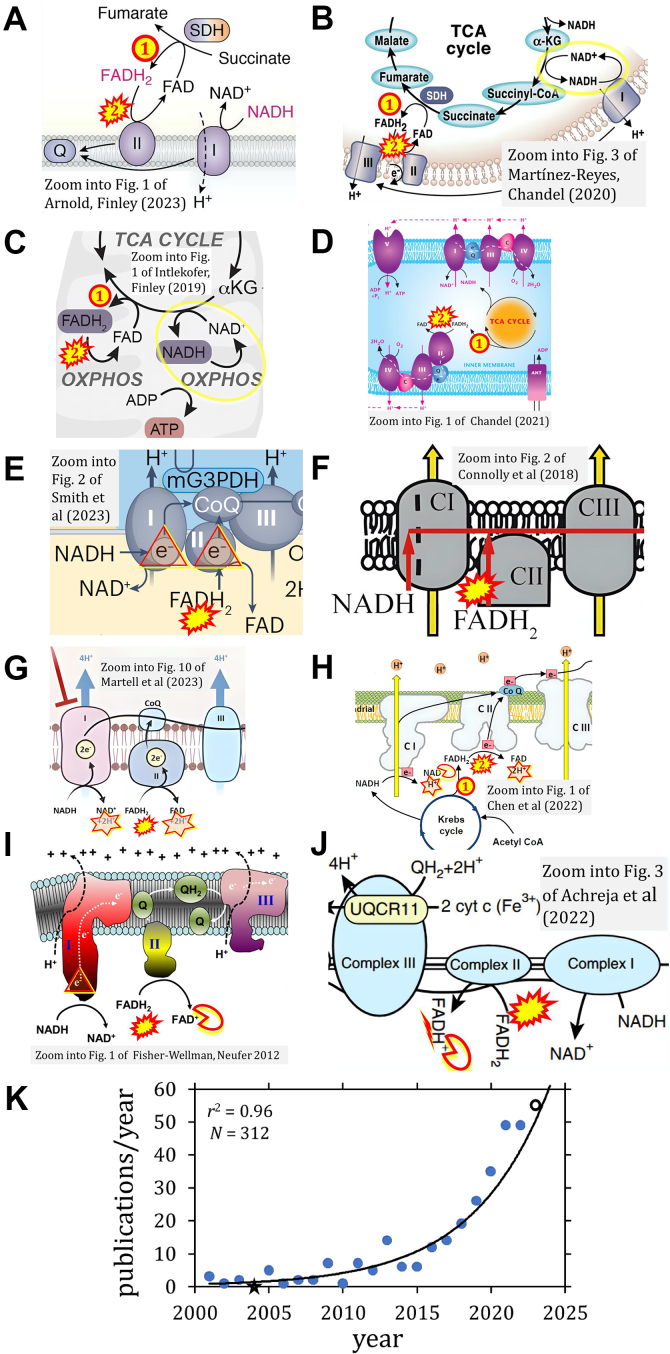

Figure 3.

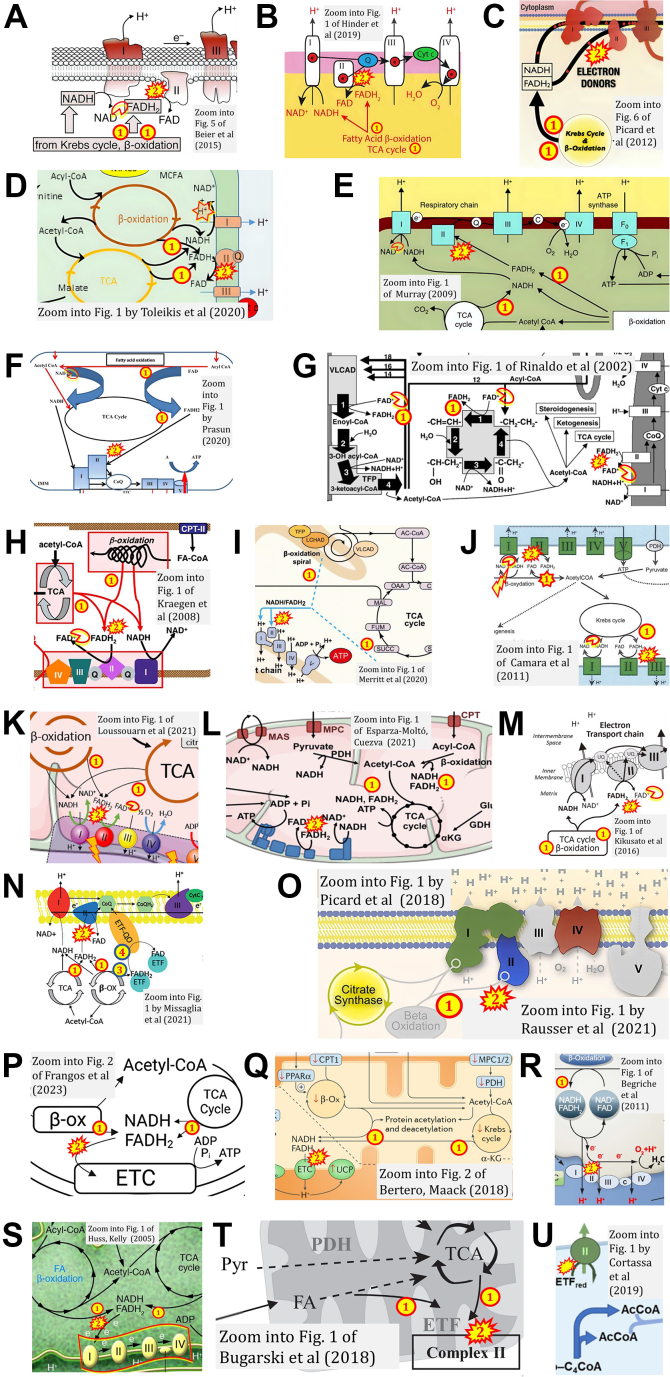

ComplexII ambiguities. FADH2 is depicted as (1) product and (2) substrate of Complex II by (A) (4), (B) (80), as in ref. (48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 104, 192, 193, 194, 199, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 209, 210, 211, 213, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 222, 225, 226, 227, 231, 233, 236, 239, 240, 241, 245, 271-280, 285, 291, 292, 293, 294, 295, 304, 305, 306, 308, 311, 312, 314, 320, 330). NADH and NAD+ cycle between different types of enzymes (yellow circle), in contrast to the FAD/FADH2 cycle located within the same enzyme molecule (SDH and CII are synonyms). C, from ambiguous NADH-FADH2 analogy (73) to (D) graphical misconception (58), as in ref. (100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 240). NADH and FADH2 at the doors of CI and CII, respectively, shown by (E) an international team (169) and (F) an international consortium suggesting guidelines (198); FADH2 cannot enter – it functions always inside CII like FAD which receives electrons from the substrate succinate. G, the redox reaction of the flavin adenine dinucleotide is copied from the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide with an unjustified indication of 2H+ formation in the mt-matrix, confusing in the context of the protonmotive force. The figure from ref. (264) is similar or identical to zooms into 33 figures from ref. (49, 57, 70, 72, 133, 154, 186, 244, 246, 249, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 257, 262, 263, 264, 267, 269, 270, 272, 273, 275, 276, 277, 278, 279, 280, 317, 319). H, the CII ambiguity in FADH2→FAD+2H+ (242, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261, 262, 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270, 271, 272, 273, 274, 275, 276, 277, 278, 279, 280) fires back at the CI-catalyzed reaction when NAD+ is shown like FAD as NAD without charge (245, 271). I, the NADH→NAD+ analogy is taken to the level of copying a charge to FAD+ ((288), as in (281, 282, 283, 284, 285, 286, 287, 288, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 294, 295, 296, 297, 298, 299, 300, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312, 313, 314, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319)) or (J) FADH+ ((331), as in (332)). K, exponential increase of publications with graphical Complex II ambiguities, 2001 to October 2023. Open symbol: the count of 46 publications in 2023 was adjusted for the full year by a multiplication factor of 12/10. Asterisc: zero count in 2004 set at 0.1 for exponential fit. N = 312 is the number of publications found with graphical CII ambiguities (Table 2).

The FADH2 - FAD confusion in the succinate-pathway

‘Like drops of water on stone, one drop will do no harm, but over time, grooves are cut deep’ (47).

The narrative that the reduced cofactors NADH and FADH2 feed electrons from the TCA cycle into the mitochondrial electron transfer system causes confusion. As a consequence, the prosthetic group FADH2 appears erroneously as the substrate of CII in the ETS linked to succinate oxidation. This error is widely propagated in publications found from 2001 to 2023 (4, 23, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 240, 241, 242, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261, 262, 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270, 271, 272, 273, 274, 275, 276, 277, 278, 279, 280, 281, 282, 283, 284, 285, 286, 287, 288, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 294, 295, 296, 297, 298, 299, 300, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312, 313, 314, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 320, 321, 322, 323, 324, 325, 326, 327, 328, 329, 330, 331, 332, 333, 334, 335, 336, 337, 338, 339, 340, 341, 342, 343, 344, 345, 346, 347, 348, 349, 350, 351, 352, 353, 354, 355) and numerous educational websites (356). The following examples illustrate the transition from ambiguity to erroneous representation.

-

(1)

Ambiguities appear in graphical representations, where FADH2 is the product of SDH and the substrate of CII – synonymous with SDH (explicit in Figure 3, A and B; implicit in Fig. 3C).

-

(2)

Ambiguity evolved to misconception in graphical representations (Fig. 3, D–F).

-

(3)

Instead of NADH+H+→NAD+ (Fig. 1A) there appears NADH→NAD+ +H+ or +2H+ and by analogy FADH2→FAD+2H+ (Fig. 3, G and H). The analogy NADH→NAD+ is taken further to include a charge for FAD or even writing FADH+ (Fig. 3, I and J). Disturbing patterns are shown in various figures with analogous representations of oxidation of NADH and FADH2 (Table 2).

-

(4)

Finally, error propagation from graphical representation (Fig. 3) leads to misinformation in the text: ‘SDH reduces FAD to FADH2, which donates its electrons to complex II’; ‘each complete turn of the TCA cycle generates three NADH and one FADH2 molecules, which donate their electrons to complex I and complex II, respectively'; ‘complex I and complex II oxidize NADH and FADH2, respectively' (4).

Table 2.

Misconceptions in graphical representations of electron entry into CI and CII

| CI e-input errors | Ref. | CII e-input errors | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (45, 97, 99) | FADH2 | → FAD | (4, 23, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99)a |

| NADH | → NAD | (52, 56)b | FADH2 | → FAD | (52, 56)b |

| NAD | → NADH | (56)c | FAD | → FADH2 | (56)c |

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (106, 122, 156, 157, 163, 172, 181) | FADH2 | → FAD | (100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187)d |

| NADH | → NAD | (123, 125, 130, 168, 177, 184) | |||

| NADH +H+ | → NAD+ + 2H+ | (149) | |||

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (227, 238) | FADH2 | → | (188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 240)e |

| NADH | → NAD | (220, 227) | |||

| NADP | (240) | ||||

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (241) | FADH2 | → FAD + H+ | (241) |

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (242, 248, 259, 260, 261, 265, 268, 274) | FADH2 | → FAD + 2H+ | (242, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261, 262, 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270, 271, 272, 273, 274, 275, 276, 277, 278, 279, 280)f |

| NADH | → NAD + H+ | (243, 245, 271, 278) | |||

| NADH | → NAD+ + 2H+ | (244, 246, 247, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 262, 263, 264, 266, 267, 269, 270, 273, 275, 276, 277, 278, 279, 280) | |||

| NADH | → NAD + 2H+ | (272) | |||

| NADH | → NAD | (286) | FADH2 | → FAD+ | (281, 282, 283, 284, 285, 286, 287, 288, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 294, 295, 296, 297, 298, 299, 300, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310)g |

| NADH +H | → NAD+ | (307) | FADH2 | → FAD+ | (307) |

| NADH | → NAD + H+ | (311) | FADH2 | → FAD+ +H+ | (311) |

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (312) | FADH2 | → FAD+ +H+ | (312) |

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (313, 315, 316, 318) | FADH2 | → FAD+ +2H+ | (313, 314, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319) |

| NADH | → NAD+ + 2H+ | (314, 317, 319) | FADH2 | → FAD+ +2H+ | |

| FADH2 | → FAD2+ | (320) | |||

| NADH + H+ | → NADH | (321) | FADH2 | → FADH | (321, 322, 323, 324, 325, 326, 327, 328, 329) |

| NADH | → NAD | (326) | |||

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (330) | FADH2 | → FADH +H+ | (330) |

| FADH2 | → FADH+ | (331, 332)h | |||

| FADH | → | (333, 334) | |||

| NADH | → NAD + H+ | (335, 336) | FADH | → FAD | (335, 336) |

| FADH | → FAD+ | (337, 338, 339) | |||

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (340) | FADH | → FAD+ + H+ | (340) |

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (341) | FADH | → FAD+ + 2H+ | (341) |

| FADH+ | → FAD | (342) | |||

| FAD | → FADH2 | (343, 344, 345)i | |||

| FAD+ | → FADH2 | (346) | |||

| FADH2 | → FAD + 2H+ | (347)j | |||

| FADH2 | → CI → CII | (348) | |||

| ETF | → CII → CIII | (349, 350, 351, 352, 353, 354, 355)k | |||

| NADH | → NAD+ + H+ | (241) | CI | → CII → CIII | (129, 166, 171, 176, 183, 223, 241, 339, 348, 373) |

| NAD+ + H+ | → NADH | (386)l | |||

2{H+ + e-} is donated to CI in the oxidation NADH + H+ → NAD+ + 2{H+ + e-}, and to CII in the oxidation Succinate2- → Fumarate2- + 2{H+ + e-}.

FAD a substrate of SDH and FADH2 a substrate of CI (Fig. 3, A–C).

Oxidation by CI and CII of NADH and FADH2, respectively, from the TCA cycle.

Reduction by CI and CII of NAD (NAD+) and FAD from β-oxidation.

Figure 3, D and E.

Figure 3F.

Figure 3, G and H.

Figure 3I.

Figure 3J.

Electron transfer into the Q-junction does not occur from a common FADH2 pool from CII and CGpDH, as Fig. 6 of ref. (345) suggests, but through functionally separate branches converging at the Q-junction.

Paradoxically, oxidation of FADH2 is linked to oxidation of succinate with formation of FAD and fumarate and 2H+; Succinate + FADH2 → FAD + Fumarate + 2H+.

The pathway is either shown from β-oxidation to CII or explicitly from ETF to CII (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7 of ref. (386) shows reduction of NAD+ by CI, where it should be oxidation of NADH.

Clarification is required (see page 48 in ref. (6)) to counteract the accelerating propagation of a fundamental bioenergetic misunderstanding (Fig. 3K). Electron transfer from succinate in the TCA cycle to the prosthetic group FAD is a redox reaction, where oxidation (ox) of succinate yields 2{H+ + e-}—two hydrons and two electrons—which are donated in the reduction (red) of FAD to FADH2 (Table 1),

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

The net redox reaction equation is

| (1) |

Commonly the charges of succinate, fumarate (Equation (1a), (1b)), and other metabolites are not shown explicitly to simplify graphical representations of metabolic pathways. But NAD+ (oxidized) must be distinguished from NAD (total NAD+ + NADH). In 2{H+ + e−} + NAD+ → NADH+H+ the final H+ is frequently omitted (Fig. 3). One hydrogen atom is transferred directly from the hydrogen donor (e.g. malate) to NAD+ without dilution by the aqueous H+ whereas the other forms an aqueous hydrogen ion (32). The equilibrium (Equation e in Table 1) depends on pH. In contrast, Equation 1b (Equation f in Table 1) is independent of pH. The fundamental difference between 2H+ and 2{H+ + e−} in Equation e (Table 1) is lost in representations such as Figure 3, G and H.

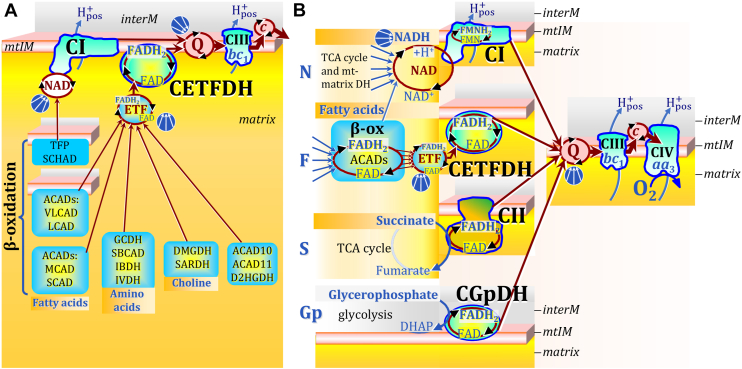

In summary, the two-electron oxidation of succinate is redox-linked to the reduction of SDHA-FAD to SDHA-FADH2, and the final electron transfer step in CII reduces UQ to UQH2. In terms of electron entry into CII, many publications show it in the wrong direction, that is, oxidation of FADH2 as an electron donor from the TCA cycle to CII (Fig. 3). This erroneous presentation has the logical consequence of putting CII into the wrong position of mitochondrial core energy metabolism. Several electron transfer pathways reduce the prosthetic group FAD of different enzymes to FADH2 and then converge separately at the Q-junction (Fig. 4). In ambiguous graphs, CII can be seen as an enzyme receiving reducing equivalents from FADH2 and thus mitigating electron transfer into the Q-junction not only from succinate in the TCA cycle but from other flavoprotein-catalyzed pathways feeding into the membrane-ETS. This is incorrect as clarified in the next sections.

Figure 4.

Convergent electron transfer into the NAD junction, ETF junction, and Q-junction indicated by convergent arrows, without showing the alignment of supercomplexes. Inter-membrane space (interM) indicated in grey and mt-matrix in yellow-orange. A, convergent FAD-linked electron transfer into the ETF junction as the first step in β-oxidation from very long- and long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (ACADS, membrane-bound), medium-, and short-chain ACADs including short/branched-ACAD (SBCAD) and Complex I assembly factor ACAD9; in branched-chain amino acid oxidation from glutaryl-CoA DH (GCDH), SBCAD, isobutyryl-CoA DH (IBDH) and isovaleryl-CoA DH (IVDH); in choline metabolism from dimethylglycine DH (DMGDH) and sarcosine DH (SARDH); and from acyl-CoA DH family members 10 and 11 (ACAD10, ACAD11) and D-2-hydroxyglutarate DH (D2HGDH). References (357, 360, 361). ETF is the redox shuttle feeding electrons into the membrane-bound electron transferring flavoprotein Complex (CETFDH on the matrix side of the mtIM) and further into Q. Steps two to four in β-oxidation of long- and medium-chain fatty acids are catalyzed by trifunctional protein (TFP, membrane-bound). Step three reduces NAD+ to NADH + H+, feeding electrons into the NAD-cycle, catalyzed by TFP and short-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCHAD). B, N: N-pathway through Complex I (CI; see Fig. 1). F: F-pathway of fatty acid oxidation through the β-oxidation cycle (β-ox) with ACADs binding noncovalently FAD; converging electron transfer through ETF to CETFDH, and dependence on the N-pathway. S: S-pathway through CII. Gp: Gp-pathway through mt-glycerophosphate DH Complex (CGpDH on the inter-membrane side of the mtIM) oxidizing glycerophosphate to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) in the inter-membrane space.

Complex II and fatty acid oxidation

In the β-oxidation cycle of fatty acid oxidation (FAO), acetyl-CoA and the reducing equivalents FADH2 and NADH are formed in reactions catalyzed by mt-membrane or matrix acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (ACADs) and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenases (HADs), respectively (357). The ACADs are flavoproteins containing FAD/FADH2 as a prosthetic group (357). The FADH2 of the ACADs is reoxidized by reducing FAD noncovalently bound to electron-transferring flavoprotein ETF (357, 358, 359, 360, 361). Comparable to electron transfer from CIII to CIV by the heme group of cytochrome c (362), the small redox protein ETF mediates the transfer of reducing equivalents from FADH2 of ACADs to the respiratory Complex of the membrane-ETS called electron flavoprotein dehydrogenase ETFDH (360) or electron transfer flavoprotein:ubiqinone oxidoreductase ETF-QO (363). This ETFDH Complex (CETFDH) receives 2{H+ + e+} from FADH2 in ETF, linking electron transfer in β-oxidation to electron entry into the Q-junction independent of CII. CETFDH and CI are the respiratory complexes involved in convergent electron entry into the Q-junction during FAO (Fig. 4). In contrast to the membrane-ETS redox shuttle cytochrome c, ETF is a matrix-ETS redox shuttle (or a redox shuttle closely associated with the mtIM on its matrix side) where multiple electron transfer pathways converge (Fig. 4A). Thus, the prosthetic group FADH2 in ETF—or simply ETF—is the substrate of CETFDH, comparable to the substrates succinate for CII, glycerophosphate for the respiratory Complex glycerophosphate dehydrogenase (CGpDH), and NADH for CI at the Q-junction, or cytochrome c for CIV (Fig. 4B). The supercomplex formed between CETFDH and CIII illustrates the CII-independent path of electron transfer from FADH2 bound to ETF into the Q-junction (360).

When FADH2 is erroneously shown free floating in the mt-matrix as a substrate of CII, a dubious role of CII in FAO is suggested as a consequence. In Figure 5, A–M, FADH2 (i) is generated by the TCA cycle and β-oxidation and (ii) donates electrons from a misconstrued “FADH2 junction” to CII (52, 56, 62, 71, 97, 218, 220, 225, 227, 283, 291, 293, 295, 299); see also (50, 236). In Figure 5N, two alternative pathways of FADH2 are shown from β-oxidation to CII and CETFDH (83), similar to ref. (84) (Fig. 6J) and ref. (201). Picard and colleagues link β-oxidation directly to CII in Figure 5O used in five publications (349, 352, 353, 354, 355). In Figure 5P, FADH2 from the TCA cycle and β-oxidation donates reducing equivalents to the “electron transport chain” (204), where “ETC-specific respiration” is considered to proceed through CI and CII. Compare with refs. (51, 104, 192, 206, 208, 215, 216, 239) (Fig. 5, Q and R). Combined with respiratory Complexes defined as CI, CII, CIII, and CIV in numerical sequence, the concept of a linear ‘electron transport chain’ ETC (in contrast to the convergent ETS) led to the presentation of linear electron flow as (NADH, FADH2) → CI → CII → CIII ((348); Fig. 5S), with a similar misconception or ambiguity in figures of refs. (129, 166, 171, 176, 183, 223, 241, 339, 373) (Table 2). Electron transfer is even shown to proceed from fatty acids through ETF to CII (350, 351) (Fig. 5, T and U).

Figure 5.

WhenFADH2is erroneously shown[1]as a substrate of CII, then[2]a dubious role of CII in oxidation of FADH2from β-oxidation is suggested as a consequence. Zoom into figures (A) (52); (B) (71); (C) (225); (D) (97); (E) (220); (F) (227); (G) (283, 299); (H) (293); (I) (218); (J) paradoxical oxidation of FADH2 and NADH in β-oxidation and reduction by CI of NAD (NAD+) from β-oxidation (56); (K) (295); (L) (62); (M) (291); (N) (83); (O) (349, 352, 353, 354, 355); (P) (204); (Q) (192); (R) (51) as in (66); (S) (348); (T) (350); (U) (351).

Figure 6.

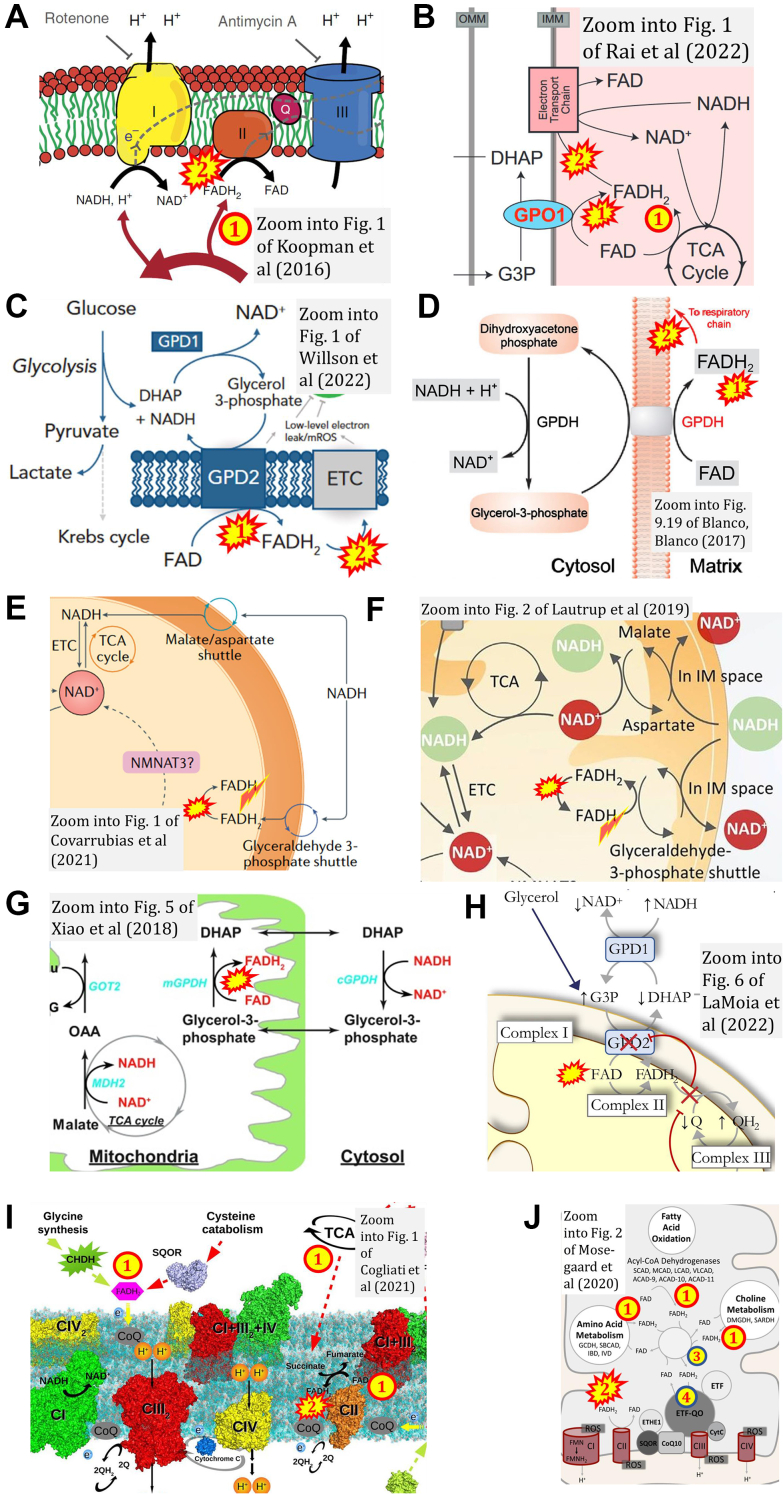

Ambiguousconclusions on a direct role of CII in the oxidation of glycerophosphate and other “FADH2-linked” pathways, analogous to false representations of CII involved in fatty acid oxidation (Fig. 5). FADH2[1] formed in the mt-matrix as a product of the TCA cycle and [2] feeding into CII: (A) (75); among 312 examples of CII-ambiguities; and FADH2[1] formed in the mt-matrix from (B) GPO1 (90), (C) GPD2 (370), or (D) GPDH (365), and [2] feeding into the ETS. GPO1, GPD2, and GPDH indicate the respiratory Complex CGpDH on the inter-membrane side of the mtIM (Fig. 4B). E–G, the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate shuttle is erroneously shown to transfer the redox pair FAD/FADH2 (not FADH/FADH2) into the mt-matrix (358, 366, 370). H, the figure (345) suggests that electron transfer into the Q-junction occurs from a common FADH2 pool generated by CII and CGpDH (GPD2). I and J, The FAD/FADH2 redox system is implicated in various electron transfer pathways independent of CII, but the CII ambiguity does not make this sufficiently clear (59, 84). FADH2 must be distinguished as a covalently bound prosthetic group of CII from a coenzyme that is attached loosely and transiently to an enzyme (385).

Lemmi et al (364) noted: ‘mitochondrial Complex II also participates in the oxidation of fatty acids’. This holds for the oxidation of acetyl-CoA generated in the β-oxidation cycle and oxidized in the TCA cycle, forming NADH and succinate with downstream electron flow through CI and CII, respectively, into the Q-junction (Fig. 1). In contrast, electron transfer from primary flavin dehydrogenases in β-oxidation proceeds through ETF, which functions as the electron (2{H+ + e-}) carrier to CETFDH.

FADH2 reducing equivalents independent of CII: glycerophosphate oxidation and ETF-linked pathways in addition to fatty acid oxidation

Comparable to the display of a putative role of CII in FAO (Fig. 5), the misconstrued pathway from FADH2 to CII has led to the incorrect notion that CII receives electrons from FADH2 formed in several branches of the ETS upstream of the Q-junction, particularly in the mitochondrial glycerophosphate DH Complex, CGpDH (59, 84, 90, 345, 365, 366, 367, 368, 369, 370). ‘FADH2 is produced by acyl CoA dehydrogenase (in the β-oxidation cycle), succinate dehydrogenase (in the TCA cycle), and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (reoxidation of NADH + H+ produced in glycolysis by the glycerol-3-phosphate shuttle). These enzymes form part of the inner mitochondrial membrane in close association with Complex II’ (208). The CII ambiguity (Fig. 6A) misleads to such direct or indirect suggestions that CII in the ETS is positioned downstream of CGpDH (Fig. 6, B–D). For carification, the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate shuttle (365, 366, 367, 368, 369, 370) does not transfer FADH2 into the mt-matrix (Fig. 6, E and F). There is no “FADH2 junction” receiving reducing equivalents and feeding electrons downstream into CII (59, 84, 345) (Fig. 6, G–J). The term “FADH2 linked substrates” (91) is ambiguous and misleading. In convergent electron transfer into the Q-junction, the independent part of CII played in the ETS is clarified by recognition of succinate (but not FADH2) as the substrate generated in the TCA cycle and feeding 2{H+ + e-} into the CII-branch of the Q-junction (Fig. 4B).

Conclusions

There is currently ambiguity surrounding the precise role of Complex II in core metabolic pathways of mitochondrial electron transfer, particularly fatty acid oxidation. While Complex II is not essential for fatty acid oxidation, it plays a regulatory role by sensing changes in metabolic demand and activating the TCA cycle for oxidation of acetyl-CoA depending on the metabolic conditions. This regulatory function may be particularly important during periods of low oxygen availability or high energy demand. The integration of FAO with the membrane-bound ETS (360) has significant implications for understanding and treating disorders related to β-oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation.

Do misinformed diagrams—from ambiguous electron transfer to the presentation of CII as an H+ pump (303, 341, 371, 372, 373) ‒ cast doubts on the quality of the publication? Authors and publishers may enjoy artistic graphs as motivational ornaments rather than informational designs. Whether using iconic or symbolic elements in graphical representations, incorporating complementary text not only enhances the communication of intended meaning but diagrams will be improved in the process. Using precisely defined terminology prevents misunderstandings (2).

When peer review provides insufficient help for corrections, post-peer review by editors and critical readers is required for revisions of articles which may be updated and re-published as living communications (374). The present review aims to raise awareness in the scientific community about the inherent ambiguity crisis, complementary to addressing the widely recognized issues of the reproducibility and credibility crisis (375). The term ‘crisis’ is rooted etymologically in the Greek word krinein: meaning to ‘separate, decide, judge’. In this sense, science and communication in general are a continuous crisis at the edge of separating clarity or certainty from confusing double meaning down to fake-news. Reproducibility relates to the condition of repeating and confirming calculations or experiments presented in a published resource. Apart from criticizing established textbooks (376), their acknowledgment with reference to expert bioenergetics reviews (11, 26) and terminological consistency (2) will pave the way out of the CII ambiguity crisis.

As defined in the introduction, the present critical review addresses type 2 ambiguities in redox reactions and bioenergetic pathways involving respiratory Complex II and electron transfer into the Q-junction. In the 312 listed references on CII ambiguities, several figures show H+ or 2H+ being formed in the oxidation of FADH2. The formation of H+ or 2H+ in the oxidation of succinate is displayed in many more references which are not included here. The ambiguous use of the symbol H+ makes no distinction between (i) 2H+ indicating reducing equivalents 2{H+ + e-} participating in oxidoreductases, (ii) H+ in chemiosmotic translocation across a membrane, and (iii) H+ in acid/base reactions (Table 2). Several type 2 CII-ambiguities, however, may be more appropriately classified as errors and incorrect representations of scientific facts, resulting from ignorance of the relevant literature. On the other side of the spectrum, we find productive type 1 ambiguities (30), when different points of view lead to innovation. A prominent case of ambiguity in the grey zone between types 1 and 2 has been uniquely demonstrated by analysis of the popular notion of “oxidative stress”—a term more frequently found than “mitochondria” in PubMed-widely used with vague definitions and without expression by numerical values and corresponding units (377). Another example closer to type 2 ambiguity is the use of the terms and experimental application of “hypoxia” and “normoxia” in bioenergetics, when air-level normoxic conditions for isolated mitochondria and cultured cells are effectively hyperoxic and may cause oxidative damage (378, 379). Another ambiguity in bioenergetics links to the confusing use of the terms uncoupling, decoupling, and dyscoupling, where rigorous definitions and distinctions are warranted (2). Linking bioenergetics to physical chemistry and the thermodynamics of irreversible processes, the ambiguous use (type 1) of the terms force and pressure (380, 381, 382, 383, 384) has deep consequences on the enigmatic concept of non-ohmic flux-force relationships in the context of mitochondrial membrane potential and the protonmotive force (6).

The present review adds Complex II ambiguities to the growing list. The trust in the science of bioenergetics is at stake — the trust of students, the general public, granting agencies, and stakeholders in the research-based health system. Clarification instead of the perpetuation of Complex II ambiguities leads to a better representation of fundamental concepts of bioenergetics and helps to maintain the high scientific standards required for translating knowledge on metabolism into clinical solutions for mitochondrial diseases.

Conflict of interest

E. Gnaiger is editor-in-chief of Bioenergetics Communications.

Acknowledgments

I thank Luiza H Cardoso, Sabine Schmitt, and Chris Donnelly for stimulating discussions, and Paolo Cocco for expert help on the graphical abstract and Figure 1, D and E. The constructive comments of an anonymous reviewer (J Biol Chem.) are explicitly acknowledged. Contribution to the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program Grant 857394 (FAT4BRAIN).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Joan B. Broderick

References

- 1.Krebs H.A., Eggleston L.V. The oxidation of pyruvate in pigeon breast muscle. Biochem. J. 1940;34:442–459. doi: 10.1042/bj0340442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gnaiger E., Eleonor A.F., Norwahidah A.K., Ali A.R., Abumrad Nada A., Acuna-Castroviejo D., et al. MitoEAGLE Task Group. Mitochondrial physiology. Bioenerg. Commun. 2020;1:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bénit P., Goncalves J., El Khoury R., Rak M., Favier J., Gimenez-Roqueplo A.P., et al. Succinate dehydrogenase, succinate, and superoxides: a genetic, epigenetic, metabolic, environmental explosive crossroad. Biomedicines. 2022;10:1788. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10081788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold P.K., Finley L.W.S. Regulation and function of the mammalian tricarboxylic acid cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2023;299 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy M.P., O’Neill L.A.J. Krebs cycle reimagined: the emerging roles of succinate and itaconate as signal transducers. Cell. 2018;174:780–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnaiger E. Mitochondrial pathways and respiratory control. An introduction to OXPHOS analysis. 5th ed. Bioenerg. Commun. 2020 doi: 10.26124/bec:2020-0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatefi Y. The mitochondrial electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985;54:1015–1069. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.005055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thunberg T. Studien über die Beeinflussung des Gasaustausches des überlebenden Froschmuskels durch verschiedene Stoffe. Skand Arch. Physiol. 1909;22:430–436. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S., Braun H.P., Gawryluk R.M.R., Millar A.H. Mitochondrial complex II of plants: subunit composition, assembly, and function in respiration and signaling. Plant J. 2019;98:405–417. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moosavi B., Berry E.A., Zhu X.L., Yang W.C., Yang G.F. The assembly of succinate dehydrogenase: a key enzyme in bioenergetics. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019;76:4023–4042. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cecchini G. Function and structure of Complex II of the respiratory chain. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:77–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iverson T.M. Catalytic mechanisms of complex II enzymes: a structural perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1827:648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maklashina E., Iverson T.M., Cecchini G. How an assembly factor enhances covalent FAD attachment to the flavoprotein subunit of complex II. J. Biol. Chem. 2022;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochachka P.W., Somero G.N. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2002. Biochemical Adaptation: Mechanism and Process in Physiological Evolution. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller M., Mentel M., van Hellemond J.J., Henze K., Woehle C., Gould S.B., et al. Biochemistry and evolution of anaerobic energy metabolism in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:444–495. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05024-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gnaiger E. In: Surviving Hypoxia: Mechanisms of Control and Adaptation. Hochachka P.W., Lutz P.L., Sick T., Rosenthal M., Van den Thillart G., editors. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Ann Arbor, London, Tokyo: 1993. Efficiency and power strategies under hypoxia. Is low efficiency at high glycolytic ATP production a paradox? pp. 77–109. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tretter L., Patocs A., Chinopoulos C. Succinate, an intermediate in metabolism, signal transduction, ROS, hypoxia, and tumorigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1857:1086–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robb E.L., Hall A.R., Prime T.A., Eaton S., Szibor M., Viscomi C., et al. Control of mitochondrial superoxide production by reverse electron transport at complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:9869–9879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spinelli J.B., Rosen P.C., Sprenger H.G., Puszynska A.M., Mann J.L., Roessler J.M., et al. Fumarate is a terminal electron acceptor in the mammalian electron transport chain. Science. 2021;374:1227–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.abi7495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chouchani E.T., Pell V.R., Gaude E., Aksentijević D., Sundier S.Y., Robb E.L., et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2014;515:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith E., Morowitz H.J. Universality in intermediary metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:13168–13173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404922101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane N. Transformer: The Deep Chemistry of Life and Death. Profile Books; London, UK: 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBerardinis R.J., Chandel N.S. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci. Adv. 2016;2 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schöpf B., Weissensteiner H., Schäfer G., Fazzini F., Charoentong P., Naschberger A., et al. OXPHOS remodeling in high-grade prostate cancer involves mtDNA mutations and increased succinate oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1487. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15237-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy M.P., Chouchani E.T. Why succinate? Physiological regulation by a mitochondrial coenzyme Q sentinel. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022;18:461–469. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iverson T.M., Singh P.K., Cecchini G. An evolving view of Complex II – non-canonical complexes, megacomplexes, respiration, signaling, and beyond. J. Biol. Chem. 2023;299 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atallah R., Olschewski A., Heinemann A. Succinate at the crossroad of metabolism and angiogenesis: roles of SDH, HIF1α and SUCNR1. Biomedicines. 2022;10:3089. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10123089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandara A.B., Drake J.C., Brown D.A. Complex II subunit SDHD is critical for cell growth and metabolism, which can be partially restored with a synthetic ubiquinone analog. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:35. doi: 10.1186/s12860-021-00370-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goetzman E., Gong Z., Zhang B., Muzumdar R. Complex II biology in aging, health, and disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12:1477. doi: 10.3390/antiox12071477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grosholz E.R. Representation and Productive Ambiguity in Mathematics and the Sciences. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2007. p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komlódi T., Cardoso L.H.D., Doerrier C., Moore A.L., Rich P.R., Gnaiger E. Coupling and pathway control of coenzyme Q redox state and respiration in isolated mitochondria. Bioenerg. Commun. 2021;2021:3. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatefi Y., Haavik A.G., Fowler L.R., Griffiths D.E. Studies on the electron transfer system XLII. Reconstitution of the electron transfer system. J. Biol. Chem. 1962;237:2661–2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee R., Purhonen J., Kallijärvi J. The mitochondrial coenzyme Q junction and Complex III: biochemistry and pathophysiology. FEBS J. 2022;289:6936–6958. doi: 10.1111/febs.16164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pallag G., Nazarian S., Ravasz D., Bui D., Komlódi T., Doerrier C., et al. Proline oxidation supports mitochondrial ATP production when Complex I is inhibited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:5111. doi: 10.3390/ijms23095111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kearney E.B. Studies on succinic dehydrogenase. XII. Flavin component of the mammalian enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1960;235:865–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehninger A.L. 2nd edition. Worth Publishers; New York: 1975. Biochemistry. The Molecular Basis of Cell Structure and Function; p. 1104. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzagoloff A. Plenum Press; New York: 1982. Mitochondria; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vercellino I., Sazanov L.A. The assembly, regulation and function of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:141–161. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Z., Zhou X., Lai Y., Xu J., Zhang Y., Zhou S., et al. Structure of the human respiratory complex II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2216713120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karavaeva V., Sousa F.L. Modular structure of complex II: an evolutionary perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2023;1864 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2022.148916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mills E.L., Pierce K.A., Jedrychowski M.P., Garrity R., Winther S., Vidoni S., et al. Accumulation of succinate controls activation of adipose tissue thermogenesis. Nature. 2018;560:102–106. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0353-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fink B.D., Rauckhorst A.J., Taylor E.B., Yu L., Sivitz W.I. Membrane potential-dependent regulation of mitochondrial complex II by oxaloacetate in interscapular brown adipose tissue. FASEB Bioadv. 2022;4:197–210. doi: 10.1096/fba.2021-00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu C.P., Hammarström L., Newton M.D. 65 years of electron transfer. J. Chem. Phys. 2022;157 doi: 10.1063/5.0102889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bunnett J.F., Jones R.A.Y. Names for hydrogen atoms, ions, and groups, and for reactions involving them. Pure Appl. Chem. 1988;60:1115–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper G.M. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland (MA): 2000. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gnaiger E. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics of energy transformations. Pure Appl. Chem. 1993;65:1983–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wardle C. Misunderstanding misinformation. Issues Sci. Technol. 2023;39:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alzaid F., Patel V.B., Preedy V.R. In: General Methods in Biomarker Research and Their Applications. Biomarkers in Disease: Methods, Discoveries and Applications. Preedy V., Patel V.R., editors. Springer; Dordrecht: 2015. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in blood. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aye I.L.M.H., Aiken C.E., Charnock-Jones D.S., Smith G.C.S. Placental energy metabolism in health and disease-significance of development and implications for preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022;226:S928–S944. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balasubramaniam S., Yaplito-Lee J. Riboflavin metabolism: role in mitochondrial function. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2020;4:285–306. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Begriche K., Massart J., Robin M.A., Borgne-Sanchez A., Fromenty B. Drug-induced toxicity on mitochondria and lipid metabolism: mechanistic diversity and deleterious consequences for the liver. J. Hepatol. 2011;54:773–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beier U.H., Angelin A., Akimova T., Wang L., Liu Y., Xiao H., et al. Essential role of mitochondrial energy metabolism in Foxp3⁺ T-regulatory cell function and allograft survival. FASEB J. 2015;29:2315–2326. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-268409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Begum H.M., Shen K. Intracellular and microenvironmental regulation of mitochondrial membrane potential in cancer cells. Wires Mech. Dis. 2023;15:e1595. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhargava P., Schnellmann R.G. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017;13:629–646. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boukalova S., Hubackova S., Milosevic M., Ezrova Z., Neuzil J., Rohlena J. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in oxidative phosphorylation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020;1866 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camara A.K., Bienengraeber M., Stowe D.F. Mitochondrial approaches to protect against cardiac ischemia and reperfusion injury. Front. Physiol. 2011;2:13. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chakrabarty R.P., Chandel N.S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles control mammalian stem cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:394–408. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chandel N.S. Mitochondria. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2021;13 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a040543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cogliati S., Cabrera-Alarcón J.L., Enriquez J.A. Regulation and functional role of the electron transport chain supercomplexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021;49:2655–2668. doi: 10.1042/BST20210460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Beauchamp L., Himonas E., Helgason G.V. Mitochondrial metabolism as a potential therapeutic target in myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2022;36:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01416-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Du J., Sudlow L.C., Shahverdi K., Zhou H., Michie M., Schindler T.H., et al. Oxaliplatin-induced cardiotoxicity in mice is connected to the changes in energy metabolism in the heart tissue. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.05.24.542198. [preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Esparza-Moltó P.B., Cuezva J.M. Reprogramming oxidative phosphorylation in cancer: a role for RNA-binding proteins. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020;33:927–945. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ezeani M. Aberrant cardiac metabolism leads to cardiac arrhythmia. Front. Biosci. (Schol Ed. 2020;12:200–221. doi: 10.2741/S547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fahlbusch P., Nikolic A., Hartwig S., Jacob S., Kettel U., Köllmer C., et al. Adaptation of oxidative phosphorylation machinery compensates for hepatic lipotoxicity in early stages of MAFLD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:6873. doi: 10.3390/ijms23126873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fink B.D., Bai F., Yu L., Sheldon R.D., Sharma A., Taylor E.B., et al. Oxaloacetic acid mediates ADP-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial complex II-driven respiration. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:19932–19941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fromenty B., Roden M. Mitochondrial alterations in fatty liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2023;78:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gammon S.T., Pisaneschi F., Bandi M.L., Smith M.G., Sun Y., Rao Y., et al. Mechanism-specific pharmacodynamics of a novel Complex-I inhibitor quantified by imaging reversal of consumptive hypoxia with [18F]FAZA PET in vivo. Cells. 2019;8:1487. doi: 10.3390/cells8121487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goetzman E.S. Modeling disorders of fatty acid metabolism in the mouse. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011;100:389–417. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-384878-9.00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamanaka R.B., Chandel N.S. Mitochondrial metabolism as a regulator of keratinocyte differentiation. Cell Logist. 2013;3 doi: 10.4161/cl.25456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Han S., Chandel N.S. Lessons from cancer metabolism for pulmonary arterial hypertension and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021;65:134–145. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0550TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hinder L.M., Sas K.M., O’Brien P.D., Backus C., Kayampilly P., Hayes J.M., et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling has no effect on microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:881. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37376-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iakovou E., Kourti M. A comprehensive overview of the complex role of oxidative stress in aging, the contributing environmental stressors and emerging antioxidant therapeutic interventions. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022;14 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.827900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Intlekofer A.M., Finley L.W.S. Metabolic signatures of cancer cells and stem cells. Nat. Metab. 2019;1:177–188. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jaramillo-Jimenez A., Giil L.M., Borda M.G., Tovar-Rios D.A., Kristiansen K.A., Bruheim P., et al. Serum TCA cycle metabolites in Lewy bodies dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: network analysis and cognitive prognosis. Mitochondrion. 2023;71:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2023.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koopman M., Michels H., Dancy B.M., Kamble R., Mouchiroud L., Auwerx J., et al. A screening-based platform for the assessment of cellular respiration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:1798–1816. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liufu T., Yu H., Yu J., Yu M., Tian Y., Ou Y., et al. Complex I deficiency in m.3243A>G fibroblasts is alleviated by reducing NADH accumulation. Front. Physiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1164287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Luo X., Li R., Yan L.J. Roles of pyruvate, NADH, and mitochondrial Complex I in redox balance and imbalance in β cell function and dysfunction. J. Diabetes Res. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/512618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Madamanchi N.R., Runge M.S. Mitochondrial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2007;100:460–473. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258450.44413.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martínez-Reyes I., Cardona L.R., Kong H., Vasan K., McElroy G.S., Werner M., et al. Mitochondrial ubiquinol oxidation is necessary for tumour growth. Nature. 2020;585:288–292. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martínez-Reyes I., Chandel N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:102. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13668-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Massart J., Begriche K., Buron N., Porceddu M., Borgne-Sanchez A., Fromenty B. Drug-induced inhibition of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and steatosis. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2013;1:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Massoz S., Cardol P., González-Halphen D., Remacle C. In: Hippler M., editor. Vol. 30. Springer; Cham: 2017. Mitochondrial bioenergetics pathways in Chlamydomonas; pp. 59–95. (Chlamydomonas: Molecular Genetics and Physiology). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Missaglia S., Tavian D., Angelini C. ETF dehydrogenase advances in molecular genetics and impact on treatment. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021;56:360–372. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2021.1908952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mosegaard S., Dipace G., Bross P., Carlsen J., Gregersen N., Olsen R.K.J. Riboflavin deficiency-implications for general human health and inborn errors of metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3847. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nolfi-Donegan D., Braganza A., Shiva S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biol. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nsiah-Sefaa A., McKenzie M. Combined defects in oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid β-oxidation in mitochondrial disease. Biosci. Rep. 2016;36 doi: 10.1042/BSR20150295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pelletier-Galarneau M., Detmer F.J., Petibon Y., Normandin M., Ma C., Alpert N.M., et al. Quantification of myocardial mitochondrial membrane potential using PET. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2021;23:70. doi: 10.1007/s11886-021-01500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peng M., Huang Y., Zhang L., Zhao X., Hou Y. Targeting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation eradicates acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.899502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Protti A., Singer M. Bench-to-bedside review: potential strategies to protect or reverse mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced organ failure. Crit. Care. 2006;10:228. doi: 10.1186/cc5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rai M., Carter S.M., Shefali S.A., Mahmoudzadeh N.H., Pepin R., Tennessen J.M. The Drosophila melanogaster enzyme glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 is required for oogenesis, embryonic development, and amino acid homeostasis. G3 (Bethesda) 2022;12 doi: 10.1093/g3journal/jkac115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sadri S., Tomar N., Yang C., Audi S.H., Cowley A.W., Jr., Dash R.K. Effects of ROS pathway inhibitors and NADH and FADH2 linked substrates on mitochondrial bioenergetics and ROS emission in the heart and kidney cortex and outer medulla. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023;744 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2023.109690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sanchez H., Zoll J., Bigard X., Veksler V., Mettauer B., Lampert E., et al. Effect of cyclosporin A and its vehicle on cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria: relationship to efficacy of the respiratory chain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;133:781–788. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scandella V., Petrelli F., Moore D.L., Braun S.M.G., Knobloch M. Neural stem cell metabolism revisited: a critical role for mitochondria. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2023;34:446–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2023.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schwartz B., Gjini P., Gopal D.M., Fetterman J.L. Inefficient batteries in heart failure: metabolic bottlenecks disrupting the mitochondrial ecosystem. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2022;7:1161–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2022.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shen Y.A., Chen C.C., Chen B.J., Wu Y.T., Juan J.R., Chen L.Y., et al. Potential therapies targeting metabolic pathways in cancer stem cells. Cells. 2021;10:1772. doi: 10.3390/cells10071772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shinmura K. Effects of caloric restriction on cardiac oxidative stress and mitochondrial bioenergetics: potential role of cardiac sirtuins. Oxid Med. Cell Longev. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/528935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Toleikis A., Trumbeckaite S., Liobikas J., Pauziene N., Kursvietiene L., Kopustinskiene D.M. Fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial morphology changes as key modulators of the affinity for ADP in rat heart mitochondria. Cells. 2020;9:340. doi: 10.3390/cells9020340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilson N., Kataura T., Korsgen M.E., Sun C., Sarkar S., Korolchuk V.I. The autophagy-NAD axis in longevity and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33:788–802. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2023.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yusoff A.A.M., Ahmad F., Idris Z., Jaafar H., Abdullah J.M. In: Molecular Considerations and Evolving Surgical Management Issues in the Treatment of Patients with a Brain Tumor. Lichtor T., editor. InTech; London, UK: 2015. Understanding mitochondrial DNA in brain tumorigenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Arden G.B., Ramsey D.J. In: Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System. Kolb H., Fernandez E., Nelson R., editors. University of Utah Health Sciences Center; Salt Lake City (UT): 2015. Diabetic retinopathy and a novel treatment based on the biophysics of rod photoreceptors and dark adaptation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bao M.H., Wong C.C. Hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, and drug resistance in liver cancer. Cells. 2021;10:1715. doi: 10.3390/cells10071715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bayona-Bafaluy M.P., Garrido-Pérez N., Meade P., Iglesias E., Jiménez-Salvador I., Montoya J., et al. Down syndrome is an oxidative phosphorylation disorder. Redox Biol. 2021;41 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bellance N., Lestienne P., Rossignol R. Mitochondria: from bioenergetics to the metabolic regulation of carcinogenesis. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed. 2009;14:4015–4034. doi: 10.2741/3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Benard G., Bellance N., Jose C., Rossignol R. In: Mitochondrial Dynamics and Neurodegeneration. Lu B., editor. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. Relationships between mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bernardo A., De Simone R., De Nuccio C., Visentin S., Minghetti L. The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation through mechanisms involving mitochondria and oscillatory Ca2+ waves. Biol. Chem. 2013;394:1607–1614. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bețiu A.M., Noveanu L., Hâncu I.M., Lascu A., Petrescu L., Maack C., et al. Mitochondrial effects of common cardiovascular medications: the good, the bad and the mixed. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232113653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Beutner G., Eliseev R.A., Porter G.A., Jr. Initiation of electron transport chain activity in the embryonic heart coincides with the activation of mitochondrial complex 1 and the formation of supercomplexes. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bhalerao S., Clandinin T.R. Vitamin K2 takes charge. Science. 2012;336:1241–1242. doi: 10.1126/science.1223812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Billingham L.K., Stoolman J.S., Vasan K., Rodriguez A.E., Poor T.A., Szibor M., et al. Mitochondrial electron transport chain is necessary for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat. Immunol. 2022;23:692–704. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01185-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brownlee M. A radical explanation for glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1788–1790. doi: 10.1172/JCI20501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Choudhury F.K. Mitochondrial redox metabolism: the epicenter of metabolism during cancer progression. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:1838. doi: 10.3390/antiox10111838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.de Villiers D., Potgieter M., Ambele M.A., Adam L., Durandt C., Pepper M.S. The role of reactive oxygen species in adipogenic differentiation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018;1083:125–144. doi: 10.1007/5584_2017_119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Delport A., Harvey B.H., Petzer A., Petzer J.P. Methylene blue and its analogues as antidepressant compounds. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017;32:1357–1382. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ekbal N.J., Dyson A., Black C., Singer M. Monitoring tissue perfusion, oxygenation, and metabolism in critically ill patients. Chest. 2013;143:1799–1808. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Escoll P., Platon L., Buchrieser C. Roles of mitochondrial respiratory Complexes during infection. Immunometabolism. 2019;1 [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eyenga P., Rey B., Eyenga L., Sheu S.S. Regulation of oxidative phosphorylation of liver mitochondria in sepsis. Cells. 2022;11:1598. doi: 10.3390/cells11101598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Favia M., de Bari L., Bobba A., Atlante A. An intriguing involvement of mitochondria in cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1890. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Feher J. Quantitative Human Physiology. 2nd ed. Academic Press; Boston: 2017. 2.10 - ATP production II: the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Garcia-Neto W., Cabrera-Orefice A., Uribe-Carvajal S., Kowaltowski A.J., Luévano-Martínez L.A. High osmolarity environments activate the mitochondrial alternative oxidase in Debaryomyces Hansenii. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Garrido-Pérez N., Vela-Sebastián A., López-Gallardo E., Emperador S., Iglesias E., Meade P., et al. Oxidative phosphorylation dysfunction modifies the cell secretome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3374. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gasmi A., Peana M., Arshad M., Butnariu M., Menzel A., Bjørklund G. Krebs cycle: activators, inhibitors and their roles in the modulation of carcinogenesis. Arch. Toxicol. 2021;95:1161–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00204-021-02974-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Geng Y., Hu Y., Zhang F., Tuo Y., Ge R., Bai Z. Mitochondria in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension, roles and the potential targets. Front. Physiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1239643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Giachin G., Jessop M., Bouverot R., Acajjaoui S., Saïdi M., Chretien A., et al. Assembly of the mitochondrial Complex I assembly complex suggests a regulatory role for deflavination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021;60:4689–4697. doi: 10.1002/anie.202011548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gopan A., Sarma M.S. Mitochondrial hepatopathy: respiratory chain disorders- ‘breathing in and out of the liver. World J. Hepatol. 2021;13:1707–1726. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i11.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gujarati N.A., Vasquez J.M., Bogenhagen D.F., Mallipattu S.K. The complicated role of mitochondria in the podocyte. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2020;319:F955–F965. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00393.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Han S., Chandel N.S. There is no smoke without mitochondria. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019;60:489–491. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0348ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hanna D., Kumar R., Banerjee R. A metabolic paradigm for hydrogen sulfide signaling via electron transport chain plasticity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023;38:57–67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2022.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hanna J., David L.A., Touahri Y., Fleming T., Screaton R.A., Schuurmans C. Beyond genetics: the role of metabolism in photoreceptor survival, development and repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.887764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Howie D., Waldmann H., Cobbold S. Nutrient sensing via mTOR in T cells maintains a tolerogenic microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:409. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jarmuszkiewicz W., Dominiak K., Budzinska A., Wojcicki K., Galganski L. Mitochondrial coenzyme Q redox homeostasis and reactive oxygen species production. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2023;28:61. doi: 10.31083/j.fbl2803061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Javali P.S., Sekar M., Kumar A., Thirumurugan K. Dynamics of redox signaling in aging via autophagy, inflammation, and senescence. Biogerontology. 2023;24:663–678. doi: 10.1007/s10522-023-10040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jayasankar V., Vrdoljak N., Roma A., Ahmed N., Tcheng M., Minden M.D., et al. Novel mango ginger bioactive (2,4,6-trihydroxy-3,5-diprenyldihydrochalcone) inhibits mitochondrial metabolism in combination with Avocatin B. ACS Omega. 2022;7:1682–1693. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c04053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Keane P.C., Kurzawa M., Blain P.G., Morris C.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/716871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kim E.H., Koh E.H., Park J.Y., Lee K.U. Adenine nucleotide translocator as a regulator of mitochondrial function: implication in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. Korean Diabetes J. 2010;34:146–153. doi: 10.4093/kdj.2010.34.3.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Knottnerus S.J.G., Bleeker J.C., Wüst R.C.I., Ferdinandusse S., Ijlst L., Wijburg F.A., et al. Disorders of mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation and the carnitine shuttle. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2018;19:93–106. doi: 10.1007/s11154-018-9448-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kumar R., Landry A.P., Guha A., Vitvitsky V., Lee H.J., Seike K., et al. A redox cycle with complex II prioritizes sulfide quinone oxidoreductase dependent H2S oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ley-Ngardigal S., Bertolin G. Approaches to monitor ATP levels in living cells: where do we stand? FEBS J. 2022;289:7940–7969. doi: 10.1111/febs.16169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Litwack G. In: Human Biochemistry. Litwack G., editor. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA: 2018. Metabolism of fat, carbohydrate, and nucleic acids, Chapter 14; pp. 395–426. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Litwiniuk A., Baranowska-Bik A., Domańska A., Kalisz M., Bik W. Contribution of mitochondrial dysfunction combined with NLRP3 inflammasome activation in selected neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14:1221. doi: 10.3390/ph14121221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]