Abstract

Traditional Chinese exercise (“TCE” management modalities), including but not limited to Tai Chi, Baduanjin, and Yijinjing, has a good effect on improving the physical function of patients with knee osteoarthritis, but less attention has been paid to the impact on the psychological health of patients, and currently there is insufficient evidence to support it. We conducted this study to provide a systematic synthesis of best evidence regarding the physical and mental health of patients with knee osteoarthritis treated by traditional Chinese exercise. Literature on the effectiveness of traditional Chinese exercise (Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Yijinjing, Qigong, etc.) versus conventional therapy (muscle‐strength training of the lower extremity and aerobic training, wellness education, quadriceps strengthening exercises, etc.) on Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), visual analog scale (VAS), Short Form‐36 (SF‐36), Timed Up and Go Test (TUG), and Berg Balance Scale (BBS) in knee osteoarthritis (KOA) from Pubmed, Web of Science, Ovid Technologies, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database (VIP), Wanfang Database, and SinoMed were collected from their inception to April 2022. Thirty‐three studies with 2621 cases were included in this study. The study's results indicated that compared with conventional therapy, traditional Chinese exercise had more advantages on patients' WOMAC score, significantly reducing patients' overall WOMAC score (SMD = −0.99; 95% CI: −1.38, −0.60; p < 0.00001) and relieving pain (SMD = −0.76; 95% CI: −1.11, −0.40; p < 0.0001) in patients with KOA. It also has advantages over conventional therapy in improving mental component score (MCS) (SMD = 0.32; 95% CI: −0.00, 0.65; p = 0.05) and physical component score (PCS) (SMD = 0.34; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.62; p = 0.02). Compared with conventional therapy, traditional Chinese exercise can significantly reduce the effect on timed up and go test (TUG) score (SMD = −0.30; 95% CI: −0.50, −0.11; p = 0.002), beck depression inventory (DBI) score (SMD = −0.62; 95% CI: −1.03, −0.22; p = 0.002), and increase the impact on Berg Balance Scale (BBS) score (SMD = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.83; p < 0.00001). The findings of this study indicated that traditional Chinese exercise improved body function and mental health in patients with knee osteoarthritis significantly. More high‐quality clinical evidence‐based data was needed to confirm the therapeutic effect of traditional Chinese exercise on the physical and mental health in KOA patients.

Keywords: Knee Osteoarthritis, Meta‐analysis, Physical Health, Psychological Health, Traditional Chinese Exercise

Traditional Chinese exercise (TCE) such as Tai Chi has a good effect on improving the physical function of patients with knee osteoarthritis, but less attention has been paid to the impact on the psychological health of patients, and there is currently a lack of sufficient evidence to support it. The aim of this systematic review and meta‐analysis was to update, synthesize, and present the best available evidence on the patient physical and mental health based on TCE management modalities in KOA. TCE significantly improved physical function and mental health in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Additional high‐quality evidence is required to confirm the effect of TCE therapy on physical and mental health in KOA patients.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a chronic and degenerative disease of the knee joint that seriously affects the life quality of patients, leading to long‐term pain and disability, and is a cause of public health problem. 1 , 2 , 3 According to reports, as early as 2017, the number of patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis alone exceeded 300 million worldwide. 4 No complete cure for KOA currently exists. The treatment modalities of KOA can be mainly categorized as pharmacological and non‐pharmacological; the non‐pharmacological treatment usually refers to surgical treatment represented by joint reconstruction, which is more suitable for patients with advanced KOA or if pharmacological therapies fail. 5 , 6 However, long‐term usage of symptom‐relieving agent or intra‐articular injections can consequentially have a range of adverse reactions, such as gastrointestinal adverse reactions, joint swelling and pain, etc. 7 , 8 , 9

In recent years, kinesitherapy has emerged in the management of KOA, research shows that exercise enhance the muscles around the thigh, thereby increasing stability around the knee joint, and reducing the loss of knee cartilage, 10 , 11 and studies have shown that non‐pharmacological therapy, including physical, mental, and mind–body exercises, are effective and safe. 12 Therefore, kinesitherapy is highly recommended by many professional academic organizations, including the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), 13 the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI), 14 and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). 6 In a series of exercise therapies, traditional Chinese exercise (TCE) such as Tai Chi have attracted much attention. Tai Chi is characterized by soft, slow, symmetrical movements and musculoskeletal stretching, which can play an active therapeutic role in the management of chronic diseases, including but not limited to KOA. 15 , 16 , 17 In addition, other TCE management modalities such as Yijinjing, Baduanjin, Wuqinxi also have a good therapeutic effect on chronic diseases including KOA. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21

Previous studies have mostly focused on symptoms such as pain in KOA patients to improve physical condition. 22 However, as a multicomponent mind–body practice, TCE can not only help improve physical health but also benefit psychological health among patients with chronic disorders. 23 Studies have shown that TCE such as Tai Chi has an impact on specific brain areas of the brain, 24 and the prefrontal cortex is likely a key biomarker among the multiple complex neural correlates to help an individual manage negative mental health. 25 Previous meta results point out that Tai Chi was beneficial for ameliorating physical and mental health of patients with KOA. 26 However, the authors only use one tool, MCS (from SF‐36), to check mental health. In addition, due to the influence of various factors, such as limited sample size, follow‐up time, etc., there was a large heterogeneity among different clinical studies, and some trials even have inconsistent results. 27 We hypothesis that the TCE management modalities would have a positive effect on KOA patients not only in physical health but also in mental health. Hence, we conducted this study to update, synthesize best evidence regarding the physical and mental health of patients with knee osteoarthritis treated by exercise based on TCE management modalities in KOA.

Methods

This study was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis (PRISRMA) Guidelines. 28 The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42022324882).

Literature Search

A literature search strategy was performed by two independent researchers (T.B. and Y.Y). The literature databases searched include Pubmed, Web of Science, Ovid Technologies, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database (VIP), Wanfang Database, SinoMed from their inceptions to April 2022. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and non‐MeSH used in literature search included “traditional Chinese exercise”, “Chinese exercise”, “Tai Chi”, “Yijinjing”, “Baduanjin”, “Wuqinxi”, “Qigong”, and “knee osteoarthritis”, “degenerative knee arthritis”, “KOA” and “randomized controlled trial”, “controlled clinical trial”, “randomized”, “trial”. Variations of different terms were used for corresponding databases. Appendix A shows the search strategy for the Pubmed database.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Literature was included in this study if it met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria: (i) patients who undergo knee osteoarthritis (no restrictions about age, sex, symptom intensity, or duration of disease); (ii) intervention is any type of traditional Chinese exercise (such as Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Yijinjing, etc.); (iii) the control group was treated with conventional therapy, such as muscle‐strength training of the lower extremity and aerobic training, wellness education, quadriceps strengthening exercises, etc.; (iv) the studies included were randomized controlled trials about any types of traditional Chinese exercise in the treatment of KOA, and the language only includes Chinese and English. The exclusion criteria: letters to editors, case series, case reports, animal experiments, and crossover studies were excluded.

Selecting Process

Our study selected and included the original research by consensus‐based method. All eligible original studies were reviewed separately B.T. and Y.Y. When their opinions diverge, Z.Q.J. was invited to make further conclusions. Standardized evidence forms were used to collect basic information about each original study, including study design information, participant's information, outcome indicators, etc.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures of interest in this study were Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), visual analog scale (VAS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Short Form‐36 (SF‐36), Timed Up and Go Test (TUG), Berg Balance Scale (BBS).

The WOMAC score was used to evaluate the severity of arthritis and its therapeutic efficacy according to the relevant symptoms and signs of patients. The function of the hip or knee joint was taken from three aspects: pain, stiffness, and physical function.

VAS score is widely used in pain assessment in clinical practice. The evaluation method is to use a ruler with “0” and “10” at both end points. A score of 0 indicates no pain, and a score of 10 indicates that the most severe pain that is intolerable.

BDI was developed to specifically assess the degree of depression. The entire scale consists of 21 sets of items, each with four‐sentence statements, and each preceded by a labeled Arabic number on a graded scale. When someone's self‐test total score was 10 or less, they were healthy without depression, and when the total score was greater than 25, their depression status was relatively severe.

The Short Form‐36 scale evaluates eight aspects of health‐related quality of life, which fall into two categories: Mental Component Score (MCS) and Physical Component Score (PCS). TUG and BBS are usually used together to evaluate the patient's balance function. In the TUG test, participants were timed as they rose from an arm chair, walked 3 m, turned around, and then walked back to the chair and sat down. The BBS test was also used for balance assessment, which consisted of 14 items, including simple mobility tasks (e.g., transfers, standing unsupported, sit‐to‐stand) and more difficult tasks (e.g., tandem standing, turning 360°, single‐leg stance). Both are used to assess balance ability in patients with osteoarthritis. 29 , 30

Data Extraction and Management

Endnote version X9 (Thomson Corporation, Stanford, CT, USA) software was used for preliminary evaluation of the original studies. After that, the literature selected from the preliminary evaluation was read in full for further evaluation. A data extraction form was used, and the appropriateness of the form was pilot‐tested. If no consensus was reached, a third researcher was invited to judge. The two researchers independently extracted key information from the screened original study.

Quality Assessment

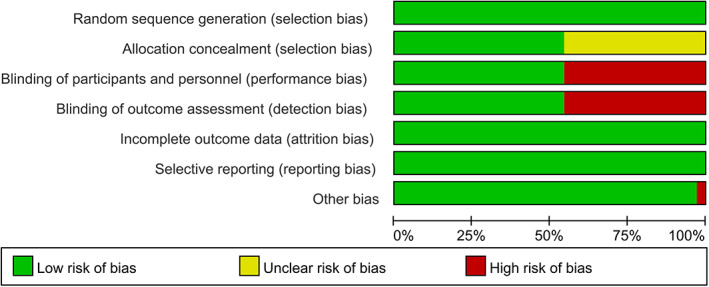

The methodological quality and the risk of bias are assessed according to the scale recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. 31 Two researchers independently evaluated the quality of the original study using Cochrane Collaboration's biased risk tool. It includes items such as random sequence generation, allocation concealment, participant and personnel blinding, result evaluation blinding, incomplete result data, and selective report. Each item is divided into high risk of bias, low risk of bias, and unclear.

Statistical Analysis

Meta‐analysis was conducted with RevMan version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK). Continuous outcomes were pooled to find the standard mean difference (SMD) and were accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Categorical outcomes were pooled to find relative risks (RRs) and were accompanied by 95% CIs. I 2 statistics were used to measure heterogeneity. The fixed effects model was appropriated when there was statistical heterogeneity (I 2 < 50%). Otherwise, the random effects model (I 2 ≥ 50%) was used. Publication bias was explored through funnel plot analysis. Egger's test was performed to identify the potential publication bias statistically.

Results

Basic Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 1059 articles were found, 440 duplicate articles were excluded, and 552 articles were excluded after reading the title and abstract, so 68 articles remained for further evaluation. Finally, 33 articles were included in this study. The flow chart of literature screening is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

All included 33 studies were published between 2003 and 2021, of which 23 were conducted in mainland China, six were conducted in the United States of America, two in South Korea, one in Iran, and one in Australia. A total of 2621 participants were included in this study, samples for a single study range from 30 to 266. All included studies were randomized controlled trials. The intervention groups included Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Yi Jin Jing, Wu Qin Xi, and Qi Gong, or one of the TCEs combined with physical therapy. Detailed information of the included studies is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| References | Region/year | Sample size (IG/CG) | Age (years) | BMI | Prescription | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Time | Frequency | Duration | ||||||

| Lee, H. J et al. 27 | Korea/2009 | 29/15 |

IG:70.20 ± 4.80 CG:66.90 ± 6.00 |

IG:26.0 ± 3.8 CG:26.0 ± 2.8 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:None |

IG:60 min | IG:Twice times per week | IG:8 weeks | MCS, PCS, SF‐36, WCOMA, 6‐MWT |

| Lee et al. 33 | USA/2017 | 41/34 |

IG:59.9 ± 10.1 CG:60.9 ± 10.8 |

IG:32.7 ± 7.0 CG:32.8 ± 7.0 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Physical therapy |

IG:60 min CG:40 min |

IG:Twice times per week CG:Three times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

ASES, BDI, MCS, PCS, PSS, WOMAC, 6‐MWT |

| An, B et al. 34 | China/2008 | 26/26 |

IG:65.4 ± 8.2 CG:64.6 ± 6.7 |

IG:25.7 ± 2.9 CG:25.4 ± 2.9 |

IG:Ba Duan Jin CG:None |

IG:30 min | IG:Five times per week | IG:8 weeks | MCS, WOMAC, 6‐MWT |

| Wang, C et al. 35 | USA/2009 | 20/20 |

IG:63 ± 8.1 CG:68 ± 7.0 |

IG:30.0 ± 5.2 CG:29.8 ± 4.3 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:The wellness education and stretching program |

IG:60 min CG:60 min |

IG:Twice times per week CG:Twice times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

ASES, MCS, PCS, VAS, WOMAC, 6‐MWT |

| Wang, C et al. 36 | USA/2016 | 106/98 |

IG:60.3 ± 10.5 CG:60.1 ± 10.5 |

IG:33.0 ± 7.1 CG:32.6 ± 7.3 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Physical therapy |

IG:60 min CG:60 min |

IG:Twice times per week CG:Twice times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

ASES, BDI, MCS, PCS, WOMAC, 6‐MWT |

| Chen FN et al. 37 | China/2020 | 55/54 |

IG:70.2 ± 5.4 CG:69.0 ± 4.9 |

IG:21.6 ± 1.3 CG:22.1 ± 1.4 |

IG:Ba duan jin CG:Routine Exercise |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Once times per day CG:Twice times per day |

IG:3 months CG:3 months |

AMP, ASES, ISKE |

| Chen YD et al. 38 | China/2021 | 25/20 |

IG:54.34 ± 7.02 CG:54.19 ± 8.41 |

IG:23.67 ± 2.38 CG:23.38 ± 2.69 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Walking |

IG:30 min CG:30 min |

IG:Five times per week CG:Five times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

SF‐36, WCOMA |

| Xiao, C et al. 39 | China/2020 | 45/40 |

IG:70.7 ± 9.36 CG:70.2 ± 10.35 |

IG:27.9 ± 4.73 CG:27.9 ± 4.75 |

IG:Wu Qin Xi CG:Physical therapy |

IG:60 min CG:NI |

IG:Four times per week CG:Four times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

BBS, ISKE, ISKF, TUG, WCOMA, 30‐SCS, 6‐MWT |

| Xiao, C. M et al. 22 | China/2021 | 34/34 |

IG:70.7 ± 9.36 CG:70.2 ± 10.35 |

IG:27.9 ± 4.75 CG:27.9 ± 4.73 |

IG:Wu Qin Xi CG:Physical therapy |

IG:60 min CG:NI |

IG:Four times per week CG:Four times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

BBS, ISKE, ISKF, TUG, WCOMA, 30‐SCS, 6‐MWT |

| Wang, F et al. 40 | China/2021 | 41/43 |

IG:64.74 ± 2.80 CG:65.70 ± 3.50 |

IG:23.94 ± 2.02 CG:23.83 ± 1.96 |

IG:Ba Duan Jin CG:Quadriceps Strengthening Exercises |

IG:20 min CG:30 ~ 40 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Three times per week |

IG:6 months CG:6 months |

ASES, MCS, PCS, WCOMA |

| Brismée et al. 41 | USA/2007 | 18/13 |

IG:70.89 ± 9.80 CG:68.89 ± 8.90 |

IG:27.96 ± 5.92 CG:27.79 ± 6.57 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Attention control |

IG:40 min CG:40 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Three times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:6 weeks |

VAS, WCOMA |

| Ye, J et al. 42 | China/2020 | 25/25 |

IG:64.48 ± 7.81 CG:63.08 ± 3.65 |

IG:24.15 ± 2.47 CG:24.56 ± 2.31 |

IG:Ba Duan Jin CG:None |

IG:40 min | IG:Three times per week | IG:12 weeks | ATE, CPAP, CPML, OPAP, OPML, TTE, WCOMA |

| Lü et al. 43 | China/2017 | 23/23 |

IG:64.61 ± 3.40 CG:64.53 ± 3.43 |

IG:25.23 ± 3.46 CG:25.05 ± 3.42 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Wellness Education |

IG:60 min CG:60 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Once times per week |

IG:24 weeks CG:24 weeks |

BBS, MCS, PCS, TUG |

| Chen, K. W et al. 44 | USA/2008 | 45/49 |

IG:63.90 ± 9.70 CG:62.90 ± 9.20 |

IG:29.6 ± 4.6 CG:31.0 ± 5.8 |

IG:Qi Gong CG:Placebo |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Twice times per week CG:Twice times per week |

IG:3 weeks CG:3 weeks |

50‐FWT |

| Li JY et al. 45 | China/2019 | 30/30 |

IG:65.80 ± 6.70 CG:66.00 ± 5.00 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Tai Chi CG:None |

IG:60 min | IG:Four times per week | IG:16 weeks | TUG, TUDS, WCOMA, 6‐MWT |

| Li TJ et al. 46 | China/2018 | 62/67 |

IG:69.50 ± 4.80 CG:69.30 ± 4.50 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Yi Jin Jing + Physical therapy CG:Physical therapy |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Once times per day CG:Once times per day |

IG:2 months CG:2 months |

ATE, CPAP, CPML, OPAP, OPML, TTE, VAS, WCOMA |

| Fransen, M et al. 47 | Australia/2007 | 56/41 |

IG:70.80 ± 6.30 CG:69.60 ± 6.10 |

IG:29.60 ± 5.90 CG:30.70 ± 5.00 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:None |

IG:60 min | IG:Twice times per week | IG:12 weeks | MCS, PCS, TUDS, TUG, WCOMA, 50‐FWT, 6‐MWT |

| Wortley M et al. 48 | USA/2013 | 56/41 |

IG:68.1 ± 5.3 CG:70.5 ± 5.0 |

IG:35.1 ± 5.9 CG:30.0 ± 6.2 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:None |

IG:60 min | IG:Twice times per week | IG:10 weeks | TUDS, TUG, WCOMA, 6‐MWT |

| Nahayatbin et al. 49 | Iran/2018 | 56/41 |

IG:55.25 ± 5.72 CG:56.06 ± 6.13 |

IG:28.98 ± 4.67 CG:28.98 ± 4.67 |

IG:Tai Chi + Physical therapy CG:Physical therapy |

IG:20 min CG:20 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Three times per week |

IG:4 weeks CG:4 weeks |

6‐MWT |

| Pan XY et al. 50 | China/2017 | 23/23 |

IG:68.61 ± 3.40 CG:64.53 ± 3.43 |

IG:25.23 ± 3.46 CG:25.05 ± 3.42 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Health Education |

IG:NI CG:60 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Once times two week |

IG:6 months CG:6 months |

BBS, ISKE, ISKF, TUG |

| Chen et al. 51 | China/2021 | 36/32 |

IG:75.40 ± 6.40 CG:77.40 ± 5.90 |

IG:24.70 ± 2.60 CG:24.00 ± 2.70 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Health Education |

IG:60 min CG:60 min |

IG:Twice times per week CG:Twice times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

30‐SCS |

| Song, R et al. 52 | Korea/2003 | 22/21 |

IG:64.8 ± 6.0 CG:62.5 ± 5.6 |

IG:24.90 ± 2.6 CG:26.37 ± 3.5 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Routine Treatment |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Three times per week CG:Three times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

WOMAC |

| Zhang, S et al. 53 | China/2022 | 22/21 |

IG:55.76 ± 8.37 CG:53.40 ± 10.66 |

IG:23.5 ± 3.23 CG:22.9 ± 2.98 |

IG:Yi Jin Jing CG:Quadriceps and Neuromuscular Training |

IG:40 min CG:40 min |

IG:Twicetimes per week CG:Twice times per week |

IG:12 weeks CG:12 weeks |

BBS, BDI, MCS, PCS, PSS, VAS, WOMAC |

| Wang CM et al. 54 | China/2016 | 30/30 |

IG:71.61 ± 4.15 CG:70.89 ± 4.93 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Ba Duan Jin CG:Meloxicam |

IG:30 min CG:7.5 mg |

IG:Five times per week CG:po.qd |

IG:3 months CG:3 months |

VAS, WOMAC |

| Xu L et al. 55 | China/2016 | 60/60 |

IG:73.44 ± 4.28 CG:69.90 ± 1.46 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Tai Chi + Dicolfenac Sodium Sustained Release Tablets CG:Dicolfenac Sodium Sustained Release Tablets |

IG:30 ~ 40 min CG:75 mg |

IG:Twice times per week CG:po.qd |

IG:2 months CG:3 months |

LKS, WOMAC |

| Yang CJ et al. 56 | China/2021 | 55/55 |

IG:69.82 ± 4.72 CG:71.54 ± 3.12 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Ba Duan Jin + Routine Rehabilitation CG:Routine Rehabilitation |

IG:30 min CG:30 min |

IG:Twice times per week CG:Twice times per week |

IG:2 months CG:2 months |

VAS, WOMAC |

| Ye JJ. 57 | China/2017 | 25/25 |

IG:61.9 ± 6.62 CG:68.9 ± 8.67 |

IG:23.39 ± 5.34 CG:23.81 ± 7.16 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:None |

IG:45 min | IG:Three times per week | IG:12 weeks | ATE, CPAP, CPML, OPAP, OPML, TTE |

| Ye YY et al. 58 | China/2019 | 26/26 |

IG:60.83 ± 9.52 CG:61.80 ± 8.26 |

IG:24.96 ± 3.13 CG:24.56 ± 1.19 |

IG:Yi Jin Jing CG:Proprioceptive Training |

IG:40 min CG:40 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Three times per week |

IG:8 weeks CG:8 weeks |

ATE, VAS, WOMAC |

| Zhao YY et al. 59 | China/2020 | 45/45 |

IG:64.00 ± 8.97 CG:61.00 ± 7.52 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Yi Jin Jing + Sodium Hyaluronate CG:Sodium Hyaluronate |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Five times per week CG:Once times per week |

IG:5 weeks CG:5 weeks |

VAS |

| Zheng YZ et al. 60 | China/2019 | 45/45 |

IG:66.25 ± 6.01 CG:67.10 ± 6.51 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Tai Chi + Glucosamine Hydrochloride CG:Glucosamine Hydrochloride |

IG:30 min CG:0.24g |

IG:Twice times per week CG:po bid |

IG:20 weeks CG:20 weeks |

ISKE, ISKF, LKS, VAS |

| Xiao, Z. et al. 61 | China/2021 | 132/134 |

IG:71 ± 2.92 CG:69 ± 3.72 |

IG:29.8 ± 7.07 CG:28.4 ± 3.7 |

IG:Wu Qin Xi CG:None |

IG:60 min | IG:Six times per week | IG:24 weeks | SF‐36, WOMAC |

| Zhou ZF. 62 | China/2019 | 15/15 |

IG:64.08 ± 1.05 CG:64.21 ± 0.98 |

IG:NI CG:NI |

IG:Tai Chi CG:None |

IG:60 ~ 90 min | IG:Twice times per week | IG:16 weeks | AMP, ISKE, VAS |

| Zhu, Q et al. 63 | China/2017 | 23/23 |

IG:64.6 ± 3.4 CG:64.5 ± 3.4 |

IG:25.2 ± 3.5 CG:25.0 ± 3.4 |

IG:Tai Chi CG:Health Education |

IG:60 min CG:60 min |

IG:Three times per week CG:Once times per week |

IG:24 weeks CG:24 weeks |

WOMAC |

Abbreviations: AMP, average muscle power; ASES, arthritis selfefficacy scale; ATE, average trace error; BBS, Berg balance scale; BDI, Beck depression inventory; CG, control group; CPAP, close eyes in anterior–posterior; CPML, close eyes in medial‐lateral; IG, intervention group; ISKE, isokinetic muscle strength testing of knee extension; ISKF, isokinetic muscle strength testing of knee flexion; LKS, Lysholm knee score; MCS, mental component score; NI, no information; OPAP, Open eyes in Anterior–Posterior; OPML, Open eyes in Medial‐Lateral; PCS, physical component score; PSS, perceived stress scale; SF‐36, Short Form 36; TTE, test time execution; TUDS, during the timed stairclimb and descent; TUG, timed up and go test; VAS, visual analog scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index; 30‐SCS, 30s chair stand test; 50‐FWT, 50‐foot walk test; 6‐MWT, 6 min walk test.

Risk of Bias and Literature Quality Assessment

The result of risk of bias and literature quality assessment for all included studies are summarized in Figures 2 and 3. The revised tool named RoB 2 for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials was used in this study. 32 All included studies provided random sequence generation. A total of 15 studies 34 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 63 did not mentional location concealment, but their baseline was uniformly comparable. For performance bias and detection bias, 15 studies 33 , 34 , 38 , 42 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 59 , 60 , 61 were at high risk of bias. All the studies were at low risk of attrition bias and reporting bias. Only one study 38 was at high risk in other bias because of incomplete result.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph.

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary (green represents low risk of bias, red represents high risk of bias, yellow represents unclear risk of bias).

Results of Meta‐Analysis

Due to the high degree of heterogeneity of meta‐analyses for some outcomes, we performed subgroup analyses for these outcomes, according to whether the patients received combination therapy.

Primary Outcome

Meta‐Analyses of WOMAC

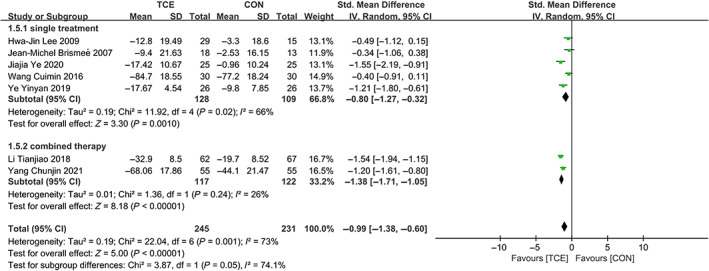

Seven trials 27 , 42 , 43 , 47 , 55 , 57 , 59 involving 476 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on overall WOMAC Score. Compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities was superior in decreasing overall WOMAC Score (SMD = −0.99; 95% CI: −1.38, −0.60; p < 0.00001, I 2 = 73%). The results of subgroup analysis, according to whether it was combination therapy, showed low heterogeneity (Figure 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on overall Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index(WOMAC) score.

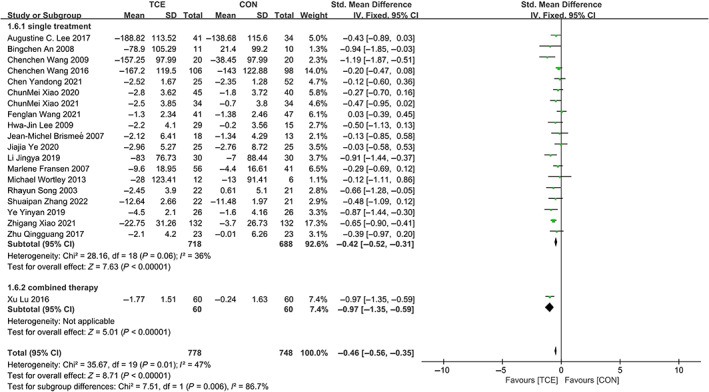

Twenty trials 22 , 27 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 57 , 61 , 63 involving 1526 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on WOMAC pain score. TCE management modalities were superior in decreasing WOMAC pain score (SMD = −0.46; 95% CI: −0.56, −0.35; p < 0.00001, I 2 = 47%) (Figure 5), funnel plot of publication bias showed in Figure 6. The p = 0.001 (t = −3.78 95% CI: −2.89, −0.83) was detected when the Egger's test was conducted to test the significance of funnel plot asymmetry.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score.

Fig. 6.

Funnel plot of publication bias.

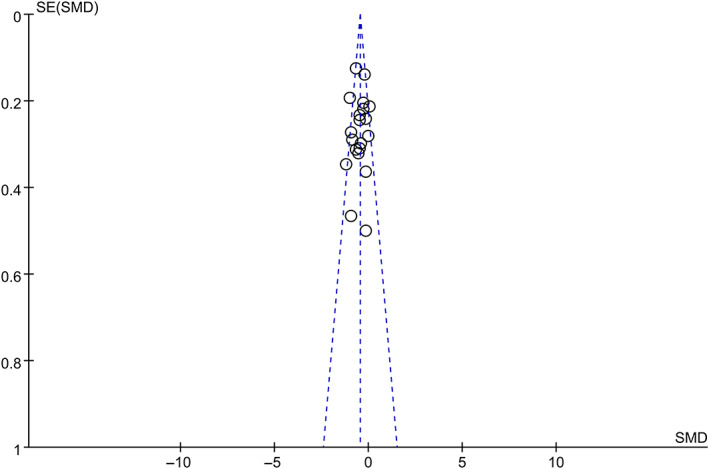

Nineteen trials 22 , 27 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 57 , 63 involving 1230 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional treatment for KOA on WOMAC physical function score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities were superior at decreasing WOMAC physical function score (SMD = −0.64; 95% CI: −0.89, −0.39; p < 0.00001, I 2 = 76%). The results of subgroup analysis, according to whether it was combination therapy, showed low heterogeneity (Figure 7).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function score.

Sixteen trials 22 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 58 , 59 , 63 involving 1191 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional treatment for KOA on WOMAC stiffness score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities were superior at decreasing WOMAC stiffness score (SMD = −0.53; 95% CI: −0.77, −0.29; p < 0.0001, I 2 = 71%). The results of subgroup analysis, according to whether it was combination therapy, showed low heterogeneity (Figure 8).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index(WOMAC) stiffness score.

Meta‐Analyses of VAS

Ten trials 35 , 41 , 46 , 53 , 54 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 62 involving 665 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on VAS score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities were superior at decreasing VAS score (SMD = −0.76; 95% CI: −1.11, −0.40; p < 0.0001, I 2 = 78%). The results of subgroup analysis, according to whether it was combination therapy, showed low heterogeneity (Figure 9).

Fig. 9.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on visual analog scale(VAS).

Secondary Outcome

Meta‐Analyses of DBI

Three trials 33 , 36 , 53 involving 322 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on DBI score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities was superior at decreasing DBI score (SMD = −0.62; 95% CI: −1.03, −0.22; p = 0.002) (Figure 10).

Fig. 10.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on Beck Depression Inventory (DBI) score.

Meta‐Analyses of MCS

Nine trials 27 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 40 , 43 , 47 , 53 involving 658 participants compared curative effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on MCS score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities were superior at increasing MCS score (SMD = 0.32; 95% CI: −0.00, 0.65; p = 0.05, I 2 = 73%) (Figure 11).

Fig. 11.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on mental component score (MCS) score.

Meta‐Analyses of PCS

Eight trials 27 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 40 , 43 , 47 , 53 involving 637 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional treatment for KOA on PCS score. However, the results showed that the two different treatment regimens did not have a relative advantage in improving PCS scores (SMD = 0.23; 95% CI: −0.09, 0.55; p = 0.16, I 2 = 73%) (Figure 12). When sensitivity analyses were performed and one study (Wang et al., 40 ) was removed, the results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities was superior decreasing PCS score (SMD = 0.34; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.62; p = 0.02, I 2 = 58%).

Fig. 12.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on physical component score (PCS) score.

Meta‐Analyses of TUG

Seven trials 22 , 39 , 43 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 50 involving 420 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on TUG score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities were superior at decreasing TUG score (SMD = −0.30; 95% CI: −0.50, −0.11; p = 0.002, I 2 = 47%) (Figure 13).

Fig. 13.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on timed up and go test (TUG) score.

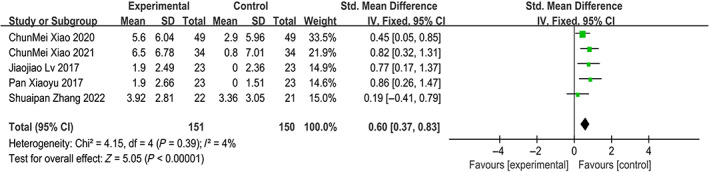

Meta‐Analyses of BBS

Five trials 22 , 39 , 43 , 50 , 53 involving 301 participants compared effect of TCE management modalities with conventional therapy for KOA on BBS score. The results showed that compared with conventional therapy, TCE management modalities were superior at increasing BBS score (SMD = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.83; p < 0.00001, I 2 = 4%) (Figure 14).

Fig. 14.

Forest plot of effects of TCE management on Berg balance scale(BBS) score.

Heterogeneity of the Pooled Results

In the present study, part of the pooled results had high heterogeneity, such as the overall WOMAC Score (I 2 = 73%). When sensitivity analyses were performed and one study 42 was deleted, heterogeneity was reduced (I 2 = 42%). The heterogeneity in WOMAC physical function score was 76%, it reduced (I 2 = 31%) after sensitivity analyses were performed and two studies 45 , 55 were removed. The heterogeneity in WOMAC stiffness score was 71%, it reduced (I 2 = 49%) after sensitivity analyses were performed and one study 42 was removed. The heterogeneity in VAS score dropped from 78% to 0%, after sensitivity analyses were performed and two studies 54 , 63 was removed. The heterogeneity in MCS score dropped from 73% to 0%, after sensitivity analyses were performed and two studies 40 , 53 were removed.

Adverse Event

Unfortunately, due to 18 adverse events of muscle soreness being reported in one study, 53 we were unable to complete the pooling of adverse events in this study. No adverse events were mentioned in the other studies. Therefore, from the available RCTs, we cannot yet draw any conclusions about the safety of TCE management modalities in patients with KOA.

Discussion

Our study involved 33 RCTs that included a total of 2621 subjects with KOA. The outcome measure primarily consisted of WOMAC, VAS, SF‐36, DBI, TUG, and BBS. The results of the meta‐analysis showed that compared with conventional functional exercise, TCE management can significantly reduce the WOMAC score of KOA patients, including the three sub‐items of pain, physical function, and stiffness. Although both exercise modalities are used to manage KOA, TCE appears to offer advantages over conventional exercise in terms of pain relief and improved balance. In terms of mental health, our study also only pooled two indicators, the MCS from SF‐36 and the DBI score. In terms of promoting mental health, TCE with a complete set of coherent motions improved mental health of patients with KOA rather than through tedious traditional limb function exercises.

There are differences between TCE management modalities and conventional functional exercise. Knee osteoarthritis is a sterile inflammation caused by damage and degeneration of knee cartilage, which can lead to pain and dysfunction of the knee joint and lifelong disability. Currently, the primary goals in knee osteoarthritis management are to relieve arthritis symptoms (e.g., pain and stiffness) and avoid disability through various pharmacological (e.g., pain relievers) or non‐pharmacological (e.g., joint replacement) treatments. However, as mentioned earlier, to our knowledge, whether it is a symptom‐relieving agent or intra‐articular injections or joint replacements, corresponding adverse events have been reported. 7 , 8 , 9 , 64 In addition, a series of studies have confirmed that the TCE management modalities such as Tai Chi are safe and highly effective for patients with KOA. 65

The uniqueness of TCE management modalities and conventional functional exercise lies in their respective exercise methods, objectives, safety, and scientificity. TCE management modalities focus on the cultivation of internal strength, including but not limited to the gentle exercise methods of Tai Chi, Qigong, Baduanjin, and Yijinjing. TCE emphasizes the unity and harmony of body and mind, aiming to prolong life. In contrast, conventional functional exercise pays more attention to external sports, such as running, swimming, yoga, strength training, etc., in order to improve physical quality, create a good body shape, and enhance sports ability and competitiveness.

Differences between Our Research and Others

The results of our research is also similar to previously reported meta‐analyses. 15 , 66 We found that there were some reports similar to our research after the literature review. However, after careful reading, it was found that previous systematic reviews have included limited literature as well as indicators. In addition, for the control group, these studies 67 , 68 included studies using different intervention protocols (i.e., strength exercise, physiotherapy, health education, or drugs) or those that did not undergo any intervention. Nevertheless the intervention measures in our study control group were all conventional exercise. In our study, some of the pooled results had high heterogeneity, such as WOMAC score, VAS score, and MCS score. After subgroup analysis, the heterogeneity was significantly reduced, so we thought that the heterogeneity might be caused by the combination with another therapy. However, after sensitivity analysis of individual indicators, individual studies needed to be excluded to reduce heterogeneity. In the initial pooled results, we found that the results of physical function (PCS score) in the SF‐36 score were insignificant, inconsistent with the physical function score conclusions in WOMAC. When sensitivity analyses were performed and after one original study was removed, the results showed that PCS score decreased in group of TCE management modalities significantly compared with the conventional therapy group. In addition to the above outcome indicators, these included original studies also focused on many other outcome indicators, but in the process of meta‐analysis, it was found that the difference between the two treatment methods was not statistically significant, so it was not shown in our study. It also suggests that more high‐quality RCT studies are needed in future studies.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study provided a relatively comprehensive literature review of the past 2 years that evaluated the effects of TCE management modalities on patients with KOA physical and mental health from RCTs. Compared with some previous systematic reviews that only focused on whether a single traditional exercise (e.g., Baduanjin) can improve pain or function in KOA patients, 20 this study not only focused on the influence of other TCE management modalities except Tai Chi on the physical function and symptoms of KOA patients, but also paid attention to the influence of these TCE management modalities on patient psychology. Relevant studies have been reported before, 60 but only two TCEs, Tai Chi and Baduanjin, were included, and relatively few original studies were included in the meta‐analysis. In addition, these studies do not pay enough attention to patient mental health.

Our study also has some limitations. Firstly, our study combined indicators of various scales like WOMAC, and when performing assessments, interference from subjective will cannot be avoided. Assessments of quantifiable biochemical markers such as inflammatory factors were lacking in the original studies. Secondly, due to traditional Chinese exercises such as Tai Chi originating in China, most of the original studies were conducted in China, and the results may be regionally biased. In addition, the results of Egger's test indicated publication bias. Finally, in available RCTs, the problem of imprecise trial design is still widespread, and more rigorous designed RCTs are needed to verify these problems in the future.

Conclusions

This systematic review represents an up‐to‐date summary of the available RCTs about the effects of TCE management modalities such as Tai Chi on physical and mental health of patients with knee OA. Compared with conventional functional exercise, traditional Chinese exercise seems to have more positive effects on WOMAC scores, VAS, TUG, and BBS scores in patients with knee OA. In addition, as evident from the SF‐36 and BDI scores, the effect of traditional Chinese exercise on the mental health of patients with knee OA may also be positive. Adverse events associated with both traditional Chinese exercise and conventional functional exercise warrant exploration in future high‐quality RCTs, and the aforementioned conclusions require more methodologically well‐designed, high‐quality RCTs with longer follow‐up periods for further validation.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval and consent are not applicable in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Biao Tan and Yan Yan collected and analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. Qiujun Zhou, Qiang Ran, and Hong Chen performed the statistical analysis. Shiyi Sun and Weizhong Lu interpreted the data. All listed authors have each made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. Professor Jiajun Wang and Professor Weiheng Chen designed the project and participated in revising it critically for content, and have approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Funding Information

This study was supported by funding for the following topics: High‐level Talent Research Project of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (2021‐XJ‐KYQD‐001); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M720596).

Acknowledgments

All listed authors have each made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; participated in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for content; and have approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Biao Tan and Yan Yan contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Weiheng Chen, Email: drchenweiheng@bucm.edu.cn.

Jiajun Wang, Email: 150006274@qq.com.

References

- 1. Bortoluzzi A, Furini F, Scirè CA. Osteoarthritis and its management‐epidemiology, nutritional aspects and environmental factors. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:1097–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Neill TW, McCabe PS, McBeth J. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors and disease outcomes of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:312–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Smith E, Hill C, Bettampadi D, Mansournia MA, et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990–2017: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:819–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin KW. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:220–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, Vaysbrot EE, Wong JB, McAlindon TE. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lopa S, Colombini A, Moretti M, de Girolamo L. Injective mesenchymal stem cell‐based treatments for knee osteoarthritis: from mechanisms of action to current clinical evidences. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:2003–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao J, Huang H, Liang G, Zeng LF, Yang W, Liu J. Effects and safety of the combination of platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, Hagen KB, Danneskiold‐Samsøe B, Dagfinrud H, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(3):CD005523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. BennellK HR. Exercise as a treatment for osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeRogatis M, Anis HK, Sodhi N, Ehiorobo JO, Chughtai M, Bhave A, et al. Non‐operative treatment options for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:S245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meiyappan KP, Cote MP, Bozic KJ, Halawi MJ. Adherence to the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons clinical practice guidelines for nonoperative management of knee osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma‐Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non‐surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:1578–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Y, Huang L, Su Y, Zhan Z, Li Y, Lai X. The effects of traditional Chinese exercise in treating knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PloS One. 2017;12:e0170237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang X, Pi Y, Chen B, Chen P, Liu Y, Wang R, et al. Effect of traditional Chinese exercise on the quality of life and depression for chronic diseases: a meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palermi S, Sacco AM, Belviso I, Marino N, Gambardella F, Loiacono C, et al. Effectiveness of tai chi on balance improvement in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2020;3:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koh TC. Baduanjin‐an ancient Chinese exercise. Am J Chin Med. 1982;10:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guo Y, Xu M, Wei Z, Hu Q, Chen Y, Yan J, et al. Beneficial effects of qigong Wuqinxi in the improvement of health condition, prevention, and treatment of chronic diseases: evidence from a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:3235950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zeng ZP, Liu YB, Fang J, Liu Y, Luo J, Yang M. Effects of Baduanjin exercise for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2020;48:102279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zou L, Zhang Y, Sasaki JE, Yeung AS, Yang L, Loprinzi PD, et al. Wuqinxi Qigong as an alternative exercise for improving risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao CM, Li JJ, Kang Y, Zhuang YC. Follow‐up of a Wuqinxi exercise at home programme to reduce pain and improve function for knee osteoarthritis in older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2021;50:570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wayne PM, Kaptchuk TJ. Challenges inherent to t'ai chi research: part I–t'ai chi as a complex multicomponent intervention. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li X, Geng J, Du X, Si H, Wang Z. Relationship between the practice of tai chi for more than 6 months with mental health and brain in university students: an exploratory study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:912276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yao Y, Ge L, Yu Q, Du X, Zhang X, Taylor‐Piliae R, et al. The effect of Tai Chi Chuan on emotional health: potential mechanisms and prefrontal cortex hypothesis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:5549006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hu L, Wang Y, Liu X, Ji X, Ma Y, Man S, et al. Tai Chi exercise can ameliorate physical and mental health of patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2021;35:64–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee HJ, Park HJ, Chae Y, Kim SY, Kim SN, Kim ST, et al. Tai Chi Qigong for the quality of life of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a pilot, randomized, waiting list controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analysis protocols (PRISMA‐P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ko PY, Li CY, Li CL, Kuo LC, Su WR, Jou IM, et al. Single injection of cross‐linked hyaluronate in knee osteoarthritis: a 52‐week double‐blind randomized controlled trial. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ribeiro IC, Coimbra AMV, Costallat BL, Coimbra IB. Relationship between radiological severity and physical and mental health in elderly individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee AC, Harvey WF, Wong JB, Price LL, Han X, Chung M, et al. Effects of tai chi versus physical therapy on mindfulness in knee osteoarthritis. Mindfulness. 2017;8:1195–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. An B, Dai K, Zhu Z, Wang Y, Hao Y, Tang T, et al. Baduanjin alleviates the symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, Kalish R, Roubenoff R, Rones R, et al. Tai Chi is effective in treating knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, Harvey WF, Fielding RA, Driban JB, et al. Comparative effectiveness of tai chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen FN, Wu WM, Le YM. Application of Baduanjin in functional exercise of elderly patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis and its effect on exercise capacity and self‐management effectiveness. Chin J Health Manage Forum. 2020;14:556–559. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen YD, Liu HG, Luo M, Jia HS, Guo YG, Zhong C. Rehabilitation effect and quality of life of Tai Chi combined with muscle strength training in patients with early and mid‐stage knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Trauma and Disability Med. 2021;29:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xiao C, Zhuang Y, Kang Y. Effects of Wu Qin xi Qigong exercise on physical functioning in elderly people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20:899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang F, Zhang X, Tong X, Zhang M, Xing F, Yang K, et al. The effects on pain, physical function, and quality of life of quadriceps strengthening exercises combined with Baduanjin qigong in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a quasi‐experimental study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22:313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brismée JM, Paige RL, Chyu MC, Boatright JD, Hagar JM, McCaleb JA, et al. Group and home‐based tai chi in elderly subjects with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ye J, Simpson MW, Liu Y, Lin W, Zhong W, Cai S, et al. The effects of Baduanjin Qigong on postural stability, proprioception, and symptoms of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Front Med. 2020;6:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lü J, Huang L, Wu X, Fu W, Liu Y. Effect of Tai Ji Quan training on self‐reported sleep quality in elderly Chinese women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trail. Sleep Med. 2017;33:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen KW, Perlman A, Liao JG, Lam A, Staller J, Sigal LH. Effects of external qigong therapy on osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:1497–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li JY, Cheng L. The effect of Taichi and resistance training on osteoarthritis symptoms of the elderly and exercise capacity. Chin J Rehabil Med. 2019;34:1304–1309. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li TJ, Li X, Zhong WH, Chen ZH, Zheng QK. Study on the mechanism of Yijinjing exercise in improving the syndrome of liver and kidney deficiency in senile degenerative knee osteoarthritis. Guangming J Chinese Med. 2018;33:3456–3459. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fransen M, Nairn L, Winstanley J, Lam P, Edmonds J. Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or Tai Chi classes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wortley M, Zhang S, Paquette M, Byrd E, Baumgartner L, Klipple G. Effects of resistance and Tai Ji training on mobility and symptoms in knee osteoarthritis patients. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nahayatbin M, Ghasemi M, Rahimi A, Khademi‐Kalantari K, Zarein‐Dolab S. The effects of routine physiotherapy alone and in combination with either tai chi or closed kinetic chain exercises on knee osteoarthritis: a comparative clinical trial study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2018;20:1–9. 10.5812/ircmj.62600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pan XY, Huang LY, Lv JJ, Wu X, Niu WX, Liu Y. Effects of innovative Tai Chi on the lower‐extremity muscle strength and dynamic balance of the elderly women with knee osteoarthritis. Sport Sci Res. 2017;38:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen PY, Song CY, Yen HY, Lin PC, Chen SR, Lu LH, et al. Impacts of tai chi exercise on functional fitness in community‐dwelling older adults with mild degenerative knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Song R, Lee EO, Lam P, Bae SC. Effects of tai chi exercise on pain, balance, muscle strength, and perceived difficulties in physical functioning in older women with osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2039–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang S, Guo G, Li X, Yao F, Wu Z, Zhu Q, et al. The effectiveness of traditional Chinese Yijinjing qigong exercise for the patients with knee osteoarthritis on the pain, dysfunction, and mood disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Front Med. 2022;8:792436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang CM, Meng LG. Clinical study on the intervention of Baduanjin in elderly knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Integr Med. 2016;4:158. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu L, Tang XZ. Effects of 24‐style simplified Tai Chi on joint function of elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Nurs. 2016;21:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang CJ, Gao XX, Zhan YW, Yuan YT, Wang YW. Effect of new horizontal Baduanjin characteristic training on elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. Chinese Manipulation and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2021;12:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ye JJ, Wang LS. The effects of Tai Chi on balance and proprioception in elderly with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled study. J Nanjing Sport Institute (Nat Sci). 2017;16:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ye YY, Niu XM, Qiu ZW, Zhong WH, Huang CW, Chen J, et al. Effect of Yijinjing on knee joint function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatism and Arthritis. 2019;8:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhao YY, Mi YQ, Gang JH, Wang HM, Chen YQ. Clinical study on Yi Jin Jing exercises combined with articular injection for early‐to‐mid osteoarthritis. Chin New Med J. 2020;52:72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zheng YZ, Zhou SB, Li MF. Observation on the therapeutic effect and mechanism of Tai Chi on patients with early knee osteoarthritis. J Tradit Chin Med. 2019;31:970–973. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xiao Z, Li G. The effect of Wuqinxi exercises on the balance function and subjective quality of life in elderly, female knee osteoarthritis patients. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:6710–6716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou ZF. The effect of Tai Chi on influence in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Chin J Geriatric Care. 2019;17:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhu Q, Huang L, Wu X, Zhang Y, Min F, Li J, et al. Effect of Taijiquan practice versus wellness education on knee proprioception in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;37:774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Oo WM, Liu X, Hunter DJ. Pharmacodynamics, efficacy, safety and administration of intra‐articular therapies for knee osteoarthritis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15:1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu B, Fan Z, Wang Z, Li M, Lu T. The efficacy and safety of Health Qigong for ankylosing spondylitis: protocol for a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Medicine. 2020;99:e18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li R, Chen H, Feng J, Xiao Y, Zhang H, Lam CW, et al. Effectiveness of traditional Chinese exercise for symptoms of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guo J, Peng C, Hu Z, Guo L, Dai R, Li Y. Effect of Wu Qin Xi exercises on pain and function in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Front Med. 2022;9:979207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhang S, Huang R, Guo G, Kong L, Li J, Zhu Q, et al. Efficacy of traditional Chinese exercise for the treatment of pain and disability on knee osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1168167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]