Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a set of complex metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycaemic condition due to defective insulin secretion (Type 1) and action (Type 2), which leads to serious micro and macro-vascular damage, inflammation, oxidative and nitrosative stress and a deranged energy homeostasis due to imbalance in the glucose and lipid metabolism. Moreover, patient with diabetes mellitus often showed the nervous system disorders known as diabetic encephalopathy. The precise pathological mechanism of diabetic encephalopathy by which it effects the central nervous system directly or indirectly causing the cognitive and motor impairment, is not completely understood. However, it has been speculated that like other extracerebellar tissues, oxidative and nitrosative stress may play significant role in the pathogenesis of diabetic encephalopathy. Therefore, the present review aimed to explain the possible association of the oxidative and nitrosative stress caused by the chronic hyperglycaemic condition with the central nervous system complications of the type 2 diabetes mellitus induced diabetic encephalopathy.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Oxidative and nitrosative stress, Cognitive and motor impairment, Diabetic encephalopathy

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic systemic metabolic disorder characterized by the increased glucose level in blood i.e., hyperglycemia. It is worldwide one of the oldest and among today’s most alarming diseases that accompanies serious complications which leads to life time medical care dependency and thus reduced quality of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged DM as one of the major non-communicable diseases. In the last few decades India emerged as one of the prime epicenters of this global health threat. According to the data provided in the 2019 edition of International Diabetes Federation (IDF), an approximate of 77 million adults (20 years and above) in India are with diabetes [1]. This data is also supported by the ongoing Indian Council of Medical Research India-Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB).

Pathogenesis of DM is mainly associated with the impaired insulin signaling which is occurred by either due to little/no production of insulin from beta-cells of pancreas, Type 1 DM (T1DM) or due to insulin resistant (IR) i.e., cells fail to respond to insulin properly, Type 2 DM (T2DM). In addition to impaired glycemic control, insulin malfunctioning leads to abnormal fat and protein metabolisms and hence increased level of lipids has been also observed in the patients of DM [2]. Both hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia cause the long-term damage of structures and functions of different body’s organs which are classified as microvascular – kidney, eyes and neurons; and macrovascular-heart and blood vessels [3–6].

Prolonged diabetic condition also causes decline in cognitive and motor function known as diabetic encephalopathy (DE). The precise pathological mechanism of DE is not completely understood. However, it is considered to be associated with the diabetes induced chronic hyperglycaemia, insulin impairments, inflammation, oxidative stress and hyperleptinemia [7]. This further adds upon mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, neuronal atrophy, impaired neurotransmitter release and synaptic reorganisation thus causing the decline in the cerebral performance [8]. Neuronal abnormalities of DM also include phosphorylation of the tau protein, amyloid breakdown and formation of neurofibrillary tangles, all of which collectively leads to the establishment of Alzheimer’s like disease (ALD) [9]. Increased apoptosis leads to loss of neurons thus accelerating the neuronal atrophy [10].

Diabetes related neuronal deficits varies in accordance with the types of DM [11, 12]. Oxidative and nitrosative stress are evidenced to be involved in the pathogenesis of T2DM in various tissues. Studies have described the underlying mechanism to be oxidative/nitrosative stress for various diabetes related complications affecting kidney, retina and peripheral nervous system described well as nephropathy, retinopathy, and peripheral neuropathy, respectively [13]. Hyperglycaemia can elevate intracellular oxidative stress through multiple mechanisms leading to inhibition of endothelium-derived synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) [14, 15]. Various theories have been proposed to explain how DM is affecting the normal physiology of the central nervous system (CNS) but the precise pathophysiological mechanism have yet not been identified clearly. This review aims to discuss the implication of diabetes induced oxidative and nitrosative stress in the pathogenesis of DE.

Diabetes Mellitus: History, Epidemiology and Types

Diabetes can be traced back to 1500 B.C, as the Egyptian manuscripts first reported this disease. These early manuscripts depicted diabetes as “too great emptying of urine” [16]. Indian physicians called it “madhumeha” meaning honey urine.

DM is one of the most spread non-communicable diseases of any population. Although the frequency of DM is more common among old age people, it has been also prevailed in adults. About 463.0 million adults have diabetes which constitute 9.3% of the total adult population of 20–79 years worldwide. Experts have predicted this number to increase up to 578.4 million and 700.2 million by 2030 and 2045 respectively. The prevalence of diabetes is more in urban areas (10.8%) than that in rural areas (7.2%). Nearly 77 million diabetic adults belong to India contributing 17% of the total diabetes cases worldwide, thus rising grave concern [1].

Depending on the abnormality in insulin secretion and its action diabetes can be differentiated into two main categories:

T1DM

It is an autoimmune response of the body where body’s natural defence system reacts in a way that it attacks the pancreatic beta cells which is responsible for the production of the glucoregulatory hormone insulin. This leads to the very deficiency of insulin. The insulin deficiency thus causes the chronic hyperglycaemia [17]. Due to its tendency of early onset, it is seen being diagnosed in children and young adults, hence, also known to be as juvenile diabetes.

T2DM

It is a heterogeneous and polygenic disorder that depend upon genetic factors with environmental influences. It is the most common form which is characterized by hyperglycaemia, IR, and relative insulin deficiency. It is estimated that 366 million people had DM in 2011; By 2030 this would have risen to 552 million. DM caused 4.6 million deaths in 2011 [1]. Environmental toxins, life style such as physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, cigarette smoking and generous consumption of alcohol is the important factor in developing DM and life style modification also plays an important role in controlling diabetes. In case of T2DM, approximately 55% of cases contributed by obesity. The increased rate of childhood obesity between the 1960s and 2000s is believed to have led to the increase in T2DM in children and adolescents [18].

The severity of T2DM as a metabolic disorder can be explained by the inefficient response to the hormone insulin causing IR [19]. Insulin resistance in case of T2DM can be observed in various organs including liver, muscles, adipose tissues and brain. This results in increased glucose production and reduced peripheral glucose uptake in liver and muscles respectively [20]. Thus, ensuring the increased blood glucose level leading to a chronic hyperglycaemic condition.

Prevalence and Economic Burden of DE

Both T1DM and T2DM are prevailing worldwide, however there has been a rapid increase in the incidence of T2DM, particularly in the developing countries. This is mainly because of growing industrialization in the developing countries, leading to reduced physical activity and thus increasing obesity which is one of the many underlying factors responsible for the prevalence of this disease. As per various studies it has been found that 90–95% are of T2DM and rest 5–10% are that of T1DM [1].

Higher medical cost and reduced quality of life due to DM imposes an alarming substantial burden on both individual and the society. Last three decades witnessed noticeable contribution of India to the steadily increasing global burden. Several cross-sectional surveys conducted across India have reported its contribution to the global prevalence of diabetes [21]. The association of DM and neurodegeneration in recent years have been inevitable, and the increased duration of diabetes is seen to have increased the prevalence of diabetes associated neurodegenerative diseases [22]. The common pathophysiological mechanism among DM and encephalopathy condition involves IR condition due to several factors including oxidative stress, impaired insulin signalling, metabolic syndrome etc. This ultimate establishment of DE thus adds on to the already alarming economic and socioeconomic burden on India as well as globally. Thus, reports suggesting the contribution of DM to the socioeconomic burden could be considered equivalent to the contribution of DE on the same if not more. Not much studies or surveys have been done to report the exact percentage of the prevalence of DE or its trend in the upcoming years, however, the association of diabetes with the major neurodegenerative disorders are warning enough for the amount of substantial burden DE could lead to any country’s economy and its socio-economic status.

Table 1 includes some of the important studies that has been included in this article to support the complications associated with T2DM induced oxidative and nitrosative stress, thus leading to DE.

Table 1.

The list of some important studies included in this study

| Sl. no. | Summary of important studies described in present review | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Several micro and macrovascular complications are associated with the advancement of the diabetes mellitus condition, effecting several other major organs along with the pancreas, thus hampering the normal physiological mechanisms in diabetic patients | Chawla et al. [3] |

| 2. | Both hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia caused by T2DM hampers the glycaemic control thus causing vascular complications | Maranta et al. [6] |

| 3. | Studies have described the underlying mechanism to be oxidative/nitrosative stress for various diabetes related complications | Tiwari et al. [13] |

| 4. | Association of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction with peripheral neuropathy can be seen in case of diabetes mellitus as hyperglycaemia can elevate intracellular oxidative stress leading to inhibition of endothelium-derived synthesis of nitric oxide | Eftekharpour and Fernyhough [15] |

| 5. | Insulin signalling deficiency in brain is a major cause for the advancement of Alzheimer’s disease | Liu et al. [42] |

| 6. | ROS and oxidative stress are among the main causative factors that are responsible for the pathogenesis of T2DM via activation of various proinflammatory mediators | Akash et al. [50] |

| 7. | Diabetes induced oxidative and nitrosative stress, cause direct injury of neuronal cells by mitochondrial damage in brain | Mastrocola et al. [69] |

| 8. | The superoxide anion (O2. −) which is a ROS reacts with NO· and leads to the formation of peroxynitrites (ONOO −) which is a powerful and damaging RNS | Beckman [73] |

| 9. | Dissociation of glucokinase from insulin secretory granules enhances the process of insulin secretion, which is associated with nitric oxide synthase | Markwardt et al. [78] |

| 10. | Hyperglycaemia caused by T2DM along with insulin resistance is a major factor involved in the development of Alzheimer’s Disease | Li T et al. [88] |

| 11. | Hyperglycaemia can lead to declined microstructural integrity of white matter in brain of diabetic patient | Antenor-Dorsey et al. [92] |

| 12. | High glucose levels in the microglia also gradually progresses the inflammatory response that could possibly lead to the cognitive dysfunction in case of DE | Dimitrios et al. [101] |

Pathogenesis of DM: Impairment in Insulin Signalling

Maintenance of a normal plasma glucose concentration requires precise matching of glucose utilization and endogenous glucose production or dietary glucose delivery. Insulin secreted from the β cells of the “islets of Langerhans” of the pancreatic tissue plays a major role in the maintenance of the blood glucose levels including glucose metabolism, gene expression, cell growth and apoptosis. However, impaired insulin secretion from the β-cells or IR in peripheral tissues, decreased the glucose utilization in peripheral tissues and abnormal hepatic glucose production. This results into a chronic exposure of elevated levels of glucose and lipids in blood which triggers the various pathogenic pathways that are responsible to induce severe structural and functional impairment in several bodies organs. Following literature attempts to discourse the pathophysiological role of insulin signalling in extracerebral tissues and the brain.

Insulin Signalling in Extracerebral Tissues: Liver, Pancreas and Muscles

Insulin receptors are expressed on insulin responsive cells like muscle and adipose tissues. Two important signalling molecules activated during insulin signalling are: Rat sarcoma (Ras) protein and phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase (PI3K) enzyme.

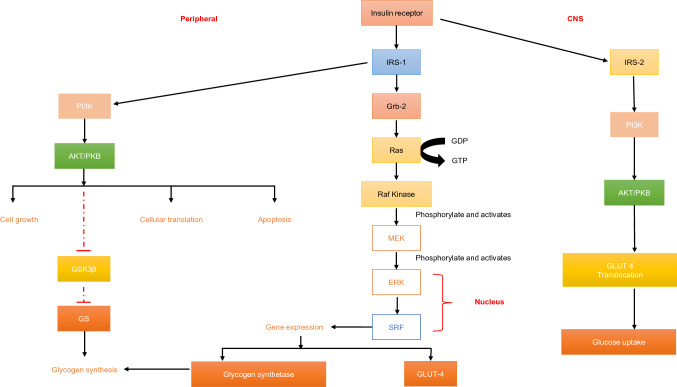

Upon insulin binding, receptor dimerization occurs. Autophosphorylation of the insulin receptor and then phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) occurs on its tyrosine residue. IRS-1 having Src homology 2 (SH-2) domain interacts with an adaptor protein Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb-2). On the other side Grb-2 contain SH-3 domain which interacts with a guanine nucleotide exchange factor of Ras protein, son of sevenless (SOS) protein. Active Ras protein interacts with N-terminal end of Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (Raf) kinases and produces conformational change which downstream phosphorylate and activate mitogen activated protein kinase (MEK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) that promotes cell proliferation and protein synthesis [23]. ERK upon activation translocate into the nucleus and it causes phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors like serum response factor (SRF) (Fig. 1). Activated transcription factors induces expression of insulin responsive genes like glycolytic genes, glycogen synthesis genes, glucose transporter-4 (GLUT-4) etc. The main function of GLUT-4 is to carry out large influx of glucose.

Fig. 1.

Insulin signalling in peripheral tissues and CNS: The insulin signalling pathway tends to vary with respect to the IRS adaptor molecule in peripheral tissues and in brain. Signalling transduction is independent of IRS 1 molecule in the brain unlike of peripheral tissues. Further transduction of signal is similar for both extracerebral tissues and CNS

Insulin signalling also activates the PI3K enzyme, which causes the conversion of Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP-2) into Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 acts as an interacting site for several cellular proteins and participates in cellular signalling responsible for cell growth, survival, translation etc.

After the commencement of the PI3K signalling the Phosphatidylinositol Phosphate (PIP) Kinase signalling is initiated. It causes phosphorylation and thus activation of serine/threonine-specific protein kinase B (AKT/PK-B). Various functions associated with AKT are promoting cell growth, cellular translation, glycogen synthesis and also apoptotic pathway by phosphorylating the pro-apoptotic BCL2 associated agonist of cell death (BAD) protein [24].

Insulin mediated glycogen metabolism is modulated through co-ordination among glucose transport and glycogen synthesis in the peripheral tissues. Insulin stimulates dephosphorylation of glycogen synthase (GS) at the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) targeted sites [25], thus inhibiting GSK-3 kinase activity and activates the glycogen-associated protein phosphatase-1 (Fig. 1).

Insulin Signalling in CNS

Previously brain was considered independent of insulin. Later, studies confirmed the implication of the action of insulin in determining the glucose and energy homeostasis. Thus, insulin de-sensitization in both extra cerebral peripheral tissues and CNS is responsible for the complications associated with diabetes. Insulin along with leptin supposedly inhibit Neuropeptide Y (NPY)/Agouti related protein (AgRP) neurons present in arcuate nucleus region of the hypothalamus that is responsible for food intake and reduction in energy expenditure [26] and stimulate the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons. This complimentary action of insulin and leptin in the neuronal circuits is responsible for the energy homeostasis [27, 28]. Insulin receptors (IRs) happens to be contained in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Hypothalamic insulin signalling is a major determinant of the normal control of glucose production by the liver. The above hypothesis could be confirmed based on the studies that confirms the infusion of insulin specific antibodies or antisense oligonucleotides in the third ventricle against the IRs increases hepatic glucose production by reducing hepatic sensitivity towards the insulin in the circulation [29].

The family of IRS adaptor molecules are crucial for the insulin signal transduction. IRS-1 was identified in some peripheral tissues to couple IRs. The interaction of the IRs and IRS-1 activates the PI3K signal transduction pathway. The role of IRS-1 in CNS insulin signal transduction is uncertain though. Normal glucose and energy homeostasis have been found in IRS-1 knockout mice [30, 31], providing evidence for IRS-1 independent insulin signalling pathway. This led to the discovery of the existence of alternative tyrosine phosphorylated protein IRS-2 to activate the PI3K signal transduction. The involvement of IRS-2 in hypothalamic insulin action regulating the energy homeostasis can be supported by the fact that mice lacking hypothalamic IRS-2 exhibited abnormal energy homeostasis in form of increased dietary intake and obesity [32, 33].

Insulin when binds to the IRs phosphorylates IRS-2 protein at the tyrosine residue results in the production of PIP3 from phosphorylation of PIP2 by the downstream activation of PI3K. This PIP3 then activates other molecules containing PIP3 binding domains among which some are Ser-Thr kinase, tyrosine kinases, GTPases, protein kinase B (PKB) i.e., AKT pathway etc. [34] (Fig. 1).

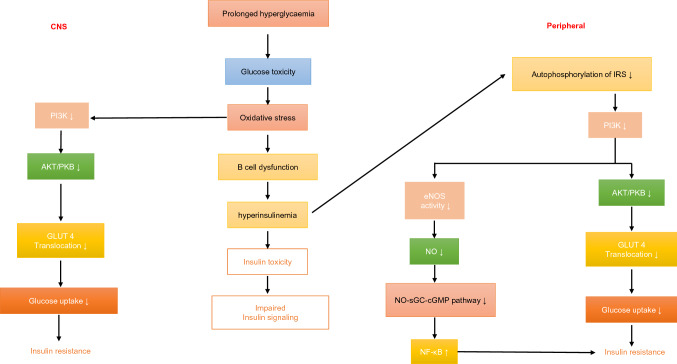

Insulin Signalling Impairment in Case of T2DM in Extracerebral Tissues: Liver, Pancreas and Muscle

Prolonged hyperglycaemic condition leads to glucose toxicity [35]. This elevated level of glucose interferes with several normal cellular functions by causing increase in oxidative stress that includes pancreatic beta cell dysfunction [36, 37]. To compensate this situation there is a long-term elevation in the level of insulin i.e., hyperinsulinemia. This abnormal increase in insulin concentration causes insulin toxicity which is the reason for the downregulation of the insulin signalling pathway. Insulin resistance results due to lesser receptor expression however, the primary reason behind that would be the impaired insulin signalling caused by the hyperinsulinemia. Prolonged hyperinsulinemia diminishes the autophosphorylation of the insulin receptor subsequently effecting the PI3K/AKT signalling cascade [38, 39]. Impaired AKT signalling cascade results in lesser translocation of GLUT-4 thus preventing the activation of glucose transport for glucose uptake. This also results in the downregulation of the e NOS activity and reduced NO production [40, 41] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Insulin signalling impairment in peripheral tissues and CNS: Diabetes results in prolonged hyperglycaemic condition which results in glucose toxicity and hyperinsulinemia which downregulates the PI3K signalling pathway thus leading to an impaired insulin signalling and Insulin resistance in some cases

Insulin Signalling Impairment in Case of T2DM in CNS

Several components of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway involved in the insulin signalling in brain have seen to be decreased both in its level and activities in case of T2DM, suggesting a possible IR condition in brain of T2DM [42]. Reduced efficiency of insulin signalling accompanied with downregulation of O-GlcNAcylation, a modification of nucleocytoplasmic protein by β-N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc) and tau hyperphosphorylation contributes to the neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [43–46]. It has been observed in several studies that T2DM adds to the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in case of AD.

Studies have shown positive correlation between some insulin signalling components and O-GlcNAcylation and negative correlation between some PI3K/AKT signalling components and tau phosphorylation at many sites suggesting a more direct relationship for T2DM induced impaired insulin signalling in CNS [42] (Fig. 2).

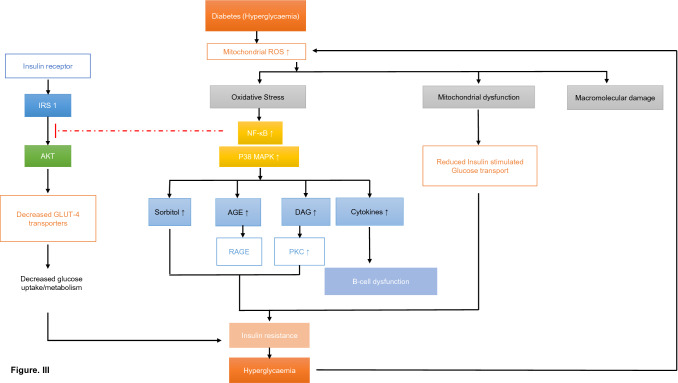

Hyperglycaemia and Oxidative Stress

The concept of oxidative stress includes disruption of redox signalling and control and/or molecular damage [47]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generates naturally during various metabolic pathways such as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and the respiratory chain associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane and leads to the synthesis of free radicals. The synthesis of these molecules is a common and important phenomenon for cell function, defence and survival [48, 49]. Various evidential studies on the pathophysiology of T2DM has revealed that ROS and oxidative stress are among the main causative factors that are responsible for the pathogenesis of IR, impaired insulin secretion and glucose utilization, abnormal hepatic glucose production and ultimately overt T2DM via activation of various proinflammatory mediators, transcriptional mediated molecular and metabolic pathways [50, 51]. Although low levels of ROS can enhance insulin action [52, 53], excessive ROS synthesis produced by elevated glucose and/or fatty acid oxidation promotes progressive mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction leading to oxidative stress, which potentially can reduce insulin secretion from β-cells as well as impair insulin signalling in target tissues. Overproduction of ROS alters cell function and induces cell death in tissues like the kidney, peripheral nerves, eyes and the vasculature [13].

Chronic hyperglycaemia has a key role in tissue damage at the sites of complications in the disease therefore oxidative stress pathways can represent an important link between high glucose levels and cell/tissue damage. The well-defined mechanisms are: the increased flux of the polyol pathway, activation of protein kinase C (PKC), the increased intracellular production of advanced glycation end products (AGE) and the increased activity of the hexosamine pathway. Under normal physiological conditions glycolysis results in mitochondrial production of superoxide anion radical (O2.−) which is balanced by the body antioxidant defence system. In hyperglycaemic conditions though the increased production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) supresses the antioxidant system that administer to oxidative nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage. DNA damage accelerates the activation of DNA repair enzyme poly-ADP-ribose polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibiting the action of glyceraldehyde-3-P dehydrogenase (GAPDH) which brings about increased levels of glyceraldehyde-3-P (GAP), fructose-6-P (F-6-P), glucose-6-P (G-6-P) and glucose subsequently. This induces subsequent accumulation of increased levels of glucose molecules in the cell i.e., chronic hyperglycaemic condition. The increased level of GAP stimulates the advanced AGE and PKC pathways; increased F-6-P and glucose levels stimulates hexosamine and polyol pathways respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress: Oxidative stress plays a key link between chronic hyperglycaemic condition and tissue damage. Reduced glucose uptake results due to the decrease in the translocation of GLUT 4 transporters which maintains the hyperglycaemic condition thus creating a continuous cycle of hyperglycaemia induced oxidative stress and vice versa

Polyol Pathway and Hexosamine Pathway

In case of the polyol pathway, the increased glucose flux forces the enzyme aldose reductase to convert the excess glucose to sorbitol. For this conversion, the enzyme consumes Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) creating a complication as NADPH is an important source to regenerate glutathione (GSH) from oxidized glutathione (GSSG). This process subsequently contributes to oxidative stress due to the depletion of the GSH pool, disturbing the intracellular defence mechanism. Chronic hyperglycaemia also activates PKC as it increases the levels of diacyl-glycerol. PKC activation leads to the increased activity of NOXes (NADPH oxidases) which again contribute to ROS production and oxidative stress. The problem with the increased formation and accumulation of AGEs through enzymatic and non-enzymatic glycation is that through these reactions, important proteins can be glycated, including those involved in the regulation of gene transcription, leading to the loss of their function. AGEs also contribute to crosslink formation in the extracellular matrix. From the oxidative stress viewpoint, modified proteins can bind to AGE receptors (RAGE), which in turn activate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), cytokine formation and proinflammatory pathways. Lastly hyperglycaemia elevates the undesired flux through the hexosamine pathway, whereas fructose-6-phosphate gets diverted from normal glycolysis. Here, the end product is UDPN-acetyl glucosamine, which in turn can modify functionally important proteins on their serine and threonine residues, resulting in aberrant changes in gene expression.

Uncoupling Protein-2 (UCP-2)

Hyperglycaemia induced oxidative stress activates the UCP-2 and thus decrease the ATP/ADP ratio, thereby inhibiting the ATP-dependent cascade of events leading to insulin secretion, release and action [54]. Moreover, hyperglycaemia mediated excess mitochondrial metabolism and production of ROS in β-cell may cause alteration in mitochondrial shape, volume and function and this may uncouple ATP-dependent K + channels leading to impairment of glucose stimulated insulin secretion [55]. Oxidative stress impairs the translocation of insulin-stimulated GLUT-4 and the activity of PKB in adipocytes [56]. Cb1 pathway, PI3K and p38MAPK pathways are the main signalling that functions collectively to translate the signal generated from insulin-receptor binding into physiological actions, such as stimulation of GLUT-4 for glucose transport [57] and utilization of glucose for protein, lipid and glycogen synthesis in target tissues [58]. Oxidative stress causes dephosphorylation and stimulates the activities of SH-2 containing protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP-1B), consequently causing IR and shutting down insulin action [59, 60].

Nuclear Factor E2 Related Factor (Nrf2)

T2DM induced oxidative/nitrosative stress plays a crucial addition in aggravating insulin resistance. Nrf2 is a basic leucine zipper transcription factor that is activated in response to increasing oxidative stress condition thus maintaining a cellular redox homeostasis. Nrf2 transcription factor is bound to Kelch-like ECH-associated protein (Keap-1) in the cytoplasm [61]. Upon ROS exposure, oxidative stress modifies Keap-1 at its cysteine residue [62, 63]. This modification of Keap-1 subsequently leads to accumulation of Nrf2 and its translocation to the nucleus where the transcription of its target genes is initiated [64, 65]. These target genes include various ROS-detoxifying enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase 2, heme oxygenase, and several glutathione S transferases. Further Nrf2 also positively modulates level of NADPH production by regulating major NADPH-generating enzymes [66]. Thus, the Nrf2 molecular pathway demonstrates satisfying suppression of oxidative stress thus maintaining redox homeostasis. The enhanced antioxidant activity could help preventing or even treating Insulin resistance. However, prolonged existence of ROS induced oxidative stress which is in case of T2DM induced chronic hyperglycaemia results in long term activation of Nrf2 resulting in metabolic stress and reduced antioxidative action thus leading to progression of the pathological condition of the disease [67].

Hyperglycaemia Induced Oxidative Stress in Brain Tissues

Oxidative phosphorylation occurring in the mitochondria is a major source of ATP. As a by-product, this process produces free radicals or ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and carbon- and sulphur-centred radicals [68]. In moderate or low amounts ROS are well chosen essential for neuronal development and function, whereas excessive levels are hazardous. It is a neurodegenerative diseases and role in the progressive nature of diseases like Parkinson’s disease (PD) and AD as well as in acute disorders such as stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Principal sources of reactive factors responsible for oxidative cell damage are mitochondria that generate ROS as a function of normal cellular processes; however, problems can occur due to an imbalance between the processes that generate and those that eliminate ROS [69]. The oxidative damage can originate from activated peripheral macrophages or brain. The production of ROS directly surpasses the scavenging capacity of antioxidant response system, lipid peroxidation happens and considerable oxidation of protein that as a result of cellular degeneration as well as oxidative damage and paradoxically lowering the function. The oxidative stress thus generated along with the hyperglycaemic condition in the regions such as cortical neurons lead to mitochondrial dysfunction that depresses the AKT signalling cascade thus generating insulin resistance [70]. Eenormous amount of ROS concentration reduces the Long-Term Potentiation (LTP), brain plasticity procedure and synaptic signalling [71]. It becomes exceptionally risky for usual operation of the brain and viewed as a circumstance of oxidative stress. Thus, the brain with its abundant lipid content, delicate antioxidant capacity and elevated energy demand becomes a target of imprudent oxidative stress. Phospholipids in the brain are particularly vulnerable entities for ROS-mediated peroxidation, but proteins and DNA also are targeted by ROS, which becomes particularly problematic during aging that show excessive measures of oxidative stress–induced mutations in the mitochondrial DNA [72]. Hence, ROS accumulation is a cellular threat that, if it exceeds or bypasses counteracting mechanisms, can cause significant neuronal damage.

Hyperglycaemia and Nitrosative Stress

The superoxide anion (O2.−) which is a ROS reacts with NO· and leads to the formation of peroxynitrites (ONOO−) which is a powerful and damaging RNS [73]. Hyperglycaemia causes reduction in the antioxidant levels and subsequently increases the production of free radicals, RONS [74]. A sustained increase in RONS contribute to the establishment and maintenance of oxidative stress, leading to endothelial dysfunction (ED), IR and alterations of pancreatic beta-cells. These results in chronic hyperglycaemic condition, which may increase the production of RONS [75], establishing a cyclic relationship between diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress, therefore triggering deleterious cellular processes, thus influencing the development of secondary diabetic complications.

Hyperglycaemia Induced Nitrosative Stress in Extracerebral Tissues

Depending upon the concentration NO can adapt dual role as in both physiological and pathological processes. NO synthesize from L-arginine by the enzyme NOS. This enzyme exists as three isoforms’ NOS 1, NOS 2 and NOS 3, discovered in the same order from 1991 to 1994 [76]. NO synthesizes from each isoform under different conditions. All of the three NOS isoforms are expressed in pancreatic β-cells.

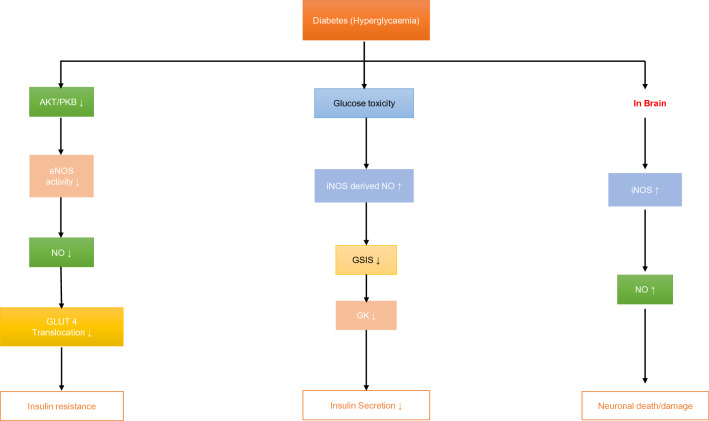

Effect of Nitrosative Stress in Inhibition of Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS)

NO derived from inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) acts as negative feedback inhibiting GSIS [77]. When synthesised in physiological levels, NO derived of the endogenous nNOS stimulates Ca2+ mobilization from the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrion increasing the cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration in addition to S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues, which initiates the GSIS and increases glucokinase (GK) activity respectively. This mediates dissociation of GK from insulin secretory granules hence, enhancing the process of insulin secretion [78]. Hyperglycaemia induced increased level of cellular glucose leads to the production of pathological levels of iNOS derived NO which inhibits the GSIS. This happens due to disturbance in the glycolytic pathway and mitochondrial respiration. The abnormal upraised NO levels lead to the formation of peroxynitrites (ONOO−). Thus, showing how nitrosative stress can interfere with insulin secretion in T2DM (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hyperglycaemia and nitrosative stress: Hyperglycaemia induced nitrosative stress leads to a decline in eNOS derived NO which reduces GLUT 4 translocation causing Insulin resistance. However, increase in the hyperglycaemia induced iNOS derived NO leads to impaired insulin secretion as well as neuronal structural impairments

Nitrosative Stress Leading to Insulin Resistance

NO promotes the expression of GLUT-4 gene thereby increasing the membranal translocation of GLUT-4 for glucose uptake [79] using the soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC)– cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) pathway. Potential cGMP-independent mechanisms involved in GLUT-4 translocation are S-nitrosylation, S-glutathionylation, and tyrosine nitration [80]. NO-sGC-cGMP pathway activates vasodilatory-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), which inhibits NF-κB activation; thereby, further inhibiting downstream inflammatory processes and enhancing insulin sensitivity [81].

Hyperglycaemia induced nitrosative stress tends to cause inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress thus leading to inhibitory phosphorylation of insulin-signalling molecules by activation of Ser/Thr kinases which ultimately results in IR [82–84] (Fig. 4).

Hyperglycaemia Induced Nitrosative Stress in Brain Tissues

Published studies have shown that diabetic animals have increased iNOS in the brain, and iNOS has been involved in many signalling pathways that enhance the development and progression of diabetic complication. High expression iNOS can overproduce NO during inflammation and activate the downstream signalling pathway of NO result in neuronal damage or death [85] (Fig. 4). Inhibiting overexpression of iNOS in brain area has beneficial effects on attenuating cognitive deficits, psychiatric disorders and neuronal injury [86]. Aminoguanidine, a selective inhibitor of iNOS, has been described to exert neuroprotection in the central nervous system against experimental stroke, inflammation, brain edema, abnormal behaviour and other brain damage. It has been reported that hyperglycaemia causes inflammation in brain and the inflammatory factor iNOS causes serious neuronal injury in diabetic animals [87]. It has been observed that iNOS and its related pathway may play key roles in the development of diabetic encephalopathy.

Diabetes Induced Neurological Impairments

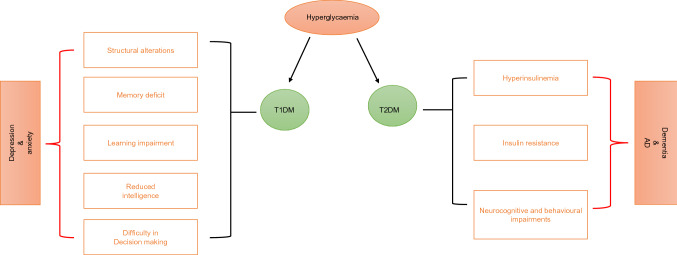

On the basis of the difference in the underlying mechanism leading to the hyperglycaemic condition in T1DM and T2DM, the nature of resulting neurocognitive and behavioural dysfunction also varies. Since, T1DM effects individuals under 18 years of age, mostly children those are below 5 years. This is the key period when the development of brain and cognitive functions takes place and the hyperglycaemia caused by T1DM retards this very developmental progress [88]. T1DM is associated with memory deficit [89], learning impairment, reduced intelligence [90] and difficulty in decision making. These can further lead to depression and anxiety. Studies have shown that anxiety and depression can result in poor glycaemic control [91]. Structural alterations are also observed in brain tissue of T1DM individuals which shows decrease in the structural integrity of the thalamus, hippocampus and superior parietal regions [92] (Fig. 5). Dementia and AD are the major extended complications of T2DM induced hyperglycaemia [93, 94]. Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance which are the characterizing features of T2DM attributes to the neurocognitive and behavioural impairments.

Fig. 5.

Diabetes induced neurological impairments: Neurocognitive and behavioural impairments vary in case of T1DM and T2DM depending on the nature of neurological dysfunction caused leading to depression and AD respectively

The impact of oxidative and nitrosative stress in β-cell dysfunction in diabetes mellitus is known already, however, remain elusive in brain tissues. The brain is supposedly more vulnerable to oxidative damage because of its high oxygen consumption rate, abundant lipid content, and relative scarcity of antioxidant enzymes as compared to other tissues. SOD, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione reductase (GR) are the main antioxidant enzymes and they utilize NADPH to maintain the endogenous level of GSH as reducing equivalents that neutralize free radicals of oxygen. NADPH is also an essential substrate for NOS activity, and thus, regulation of NADPH synthesis constitutes an important aspect of NOS regulation in the brain cells. Therefore, investigation on regulation of NADPH synthesis is equally important to understand metabolic regulation of redox status in the brain cells of T2DM rat in case of DE. G6PD is acts as an enzyme for the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and thus acts as a determinant of the endogenous NADPH synthesis in the cells. Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) is a metabolic substrate for G6PD. And studies have shown that the relative levels of G6PD vs. PFK2 effectively determine the flow of G6P in glycolysis and PPP and, thus, constitute the main biochemical mechanism to regulate PPP in the cells. There are implications of G6PD/PFK2 mechanism in certain neuropathology studies [95, 96].

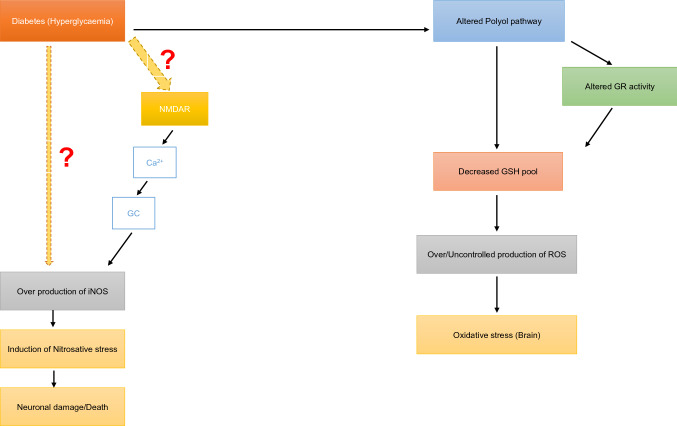

Since DE is a collective reference to the CNS complications, thus the possible pathological implications of the NMDARs cannot be ignored. NMDARs are tetrameric glutamate-gated ion channels that are widely expressed in the CNS wherein holding central roles in CNS function [97]. Moreover, NMDAR dysfunction is also associated with several neurological and psychiatric disorders such as AD, PD and depression (hyperfunction) as well as schizophrenia, cognitive impairment during ageing (hypofunction) and autism spectrum disorders [98]. Insulin plays an important role in the transient phosphorylation of NR2A and NR2B tyrosine residues of NMDAR subunits. Studies have shown an impaired NR2B phosphorylation in the absence of IRS-2 protein thus establishing a relationship between the insulin potentiation of NMDAR responses. It has also been seen that in case of T2DM induced AD which results in the accumulation of Aβ oligomers the TNF-α levels increases thus increasing the Ca2+ influx leading to the increase in nitrosative and oxidative stress.

The association of T2DM to the oxidative and nitrosative stress is known in various tissues along with their pathogenic role. Studies have confirmed the underlying mechanism to be oxidative/nitrosative stress for various diabetes related complications such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic neuropathy (DN), diabetic nephropathy and several cardiovascular diseases. However, there are very lesser-known facts about the exact mechanism how the oxidative stress and the nitrosative stress caused by T2DM effects the central nervous system directly or indirectly through various other tissue damage known already. The possible pathological implications of factors such as the relative G6PD/PFK2 levels and NMDAR dysfunction in DE are also not known (Fig. 6). So, by understanding the underlying causes of DE, it might be possible to find a more advanced and more of a synergistic drug-based treatment for T2DM in future thus allowing us to also take the extended complications of diabetes or diabetic complications under consideration thus increasing the longevity of the existing treatments and reducing the treatment related risk factors.

Fig. 6.

A possible pathogenesis of DE: Hyperglycaemia induced over production of iNOS has been reported leading to neuronal and insulin signalling impairment; however, implication of NMDAR is not clear

Parallel and Significant Mechanisms of Diabetic Encephalopathy as on Date

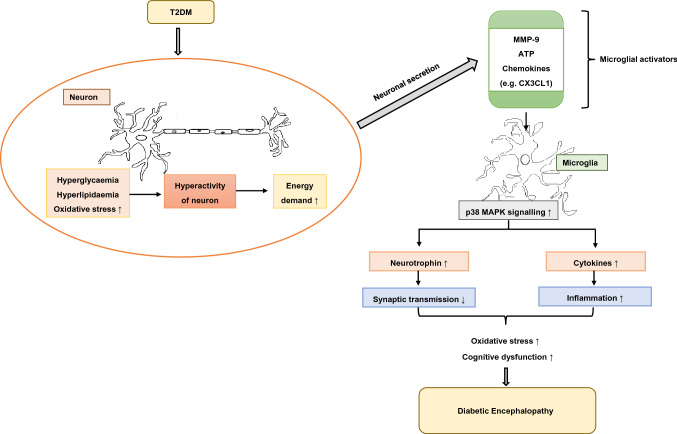

Role of Microglia–Neuron Interactions in DE

The first line of defence of the CNS from various pathogenic invasions involves the primary as well as the main immune cells, the microglia. Microglial cells act as neuroprotectors by regulating the immune response [99], identifying antibodies, and phagocytosis of digressive neurons and tissue debris [100, 101]. Along with the suppression of abnormal inflammation microglial cells also promotes synapse stripping and neurogenesis. All of this is maintained as the microglial cells remain in a constant patrol to detect any abnormalities in the neurons and astrocytes. Hyperactivity of neurons due to hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia increases the energy demand of the microglial cells. Microglial cells exhibit their own glucose transporters to ensure sufficient glucose influx to compensate the energy demand when generated due to the neuronal hyperactivity. As pros always carry along some cons, the high glucose levels in the microglia also gradually progresses the inflammatory response induced by lipopolysaccharides.

Studies have suggested, the increased activity of neurons leads to the secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), ATP and chemokines like CX3CL1. All of these acts as microglial activators which further activates the p38 MAPK. The increased production of neurotrophin regulates the synaptic transmission and an increased production of inflammatory factors is also led by the activated MAPK signalling. This increase in the destructive inflammation thus leads to the cognitive dysfunction in case of DE (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Microglia-neuron interaction: Hyperactivity of neurons induced by T2DM brings about an increase in the demand for energy to be utilised for the influx of glucose. Neurons then secrete latent microglial activators such as matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), ATP and chemokines (for example CX3CL1). These activators then target the p38 MAPK signalling by enhancing it which leads to the increase in the inflammation. The destructive increase in inflammation causes elevated oxidative stress and cognitive dysfunction thus causing DE

This chronic neuroinflammation activated microglial over secretion of proinflammatory cytokines also leads to an excessive oxidative and nitrosative stress, thus interlinking the mechanism of oxidative/nitrosative stress and microglial-neuron interaction in the escalation of the DE condition [102].

Conclusion

The rapid increase in the incidences of T2DM worldwide is a matter of great concern. Several antidiabetic drugs have been developed to cope with the pathology of this, however, yet remain unsatisfactory. Diabetes is also associated with the serious secondary complications affecting kidney, retina and peripheral nerves which are already known to us. What concerns us is the recently discovered CNS complications associated with T2DM also known as DE. Various theories have been proposed to explain how DE is affecting the normal physiology of the CNS but the precise pathological mechanism is not clearly defined. Oxidative and nitrosative stress (play a very important role in the pathophysiology of diabetes) together with alteration in NMDAR-NO-cGMP signalling and bioenergetics may contribute in the cognitive and motor deficit in case of DE likewise several other neurological disorders. Excessive oxidative and nitrosative stress also effects the microglia-neuron interaction mechanism. Neuronal hyperactivity caused by the hyperglycaemic condition is also associated with the increased oxidative stress leading to the over secretion of pro-inflammatory factors, thus leading to the cognitive dysfunction in case of DE. Abrupt increase in the oxidative stress gets interlinked with several physiological signalling mechanism thus escalating the DE condition in multiple ways. However, it is a further matter of research to testify this hypothesis as well as other possible pathogenesis in case of DE. Understanding the DE can help us design more effective antidiabetic drug or combination of drugs so as to increase the longevity and quality of diabetic patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

DM contributed in writing the manuscript. SS edited and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(3):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borén J, Taskinen MR. Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;270:133–156. doi: 10.1007/164_2021_520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chawla A, Chawla R, Jaggi S. Microvasular and macrovascular complications in diabetes mellitus: distinct or continuum? Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20(4):546–551. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.183480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou Y, Ma J, Su X, Zhong Y. Emerging insights into the relationship between hyperlipidemia and the risk of diabetic retinopathy. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-01415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26:77–82. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.26.2.77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maranta F, Cianfanelli L, Cianflone D. Glycaemic control and vascular complications in diabetes mellitus type 2. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1307:129–152. doi: 10.1007/5584_2020_514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaspar JM, Baptista FI, Macedo MP, Ambrósio AF. Inside the diabetic brain: role of different players involved in cognitive decline. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7(2):131–142. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruehl H, Sweat V, Tirsi A, Shah B, Convit A. Obese adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus have hippocampal and frontal lobe volume reductions. Neurosci Med. 2011;2:34–42. doi: 10.4236/nm.2011.21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim B, Backus C, Oh S, Feldman EL. Hyperglycemia-induced Tau cleavage in vitro and in vivo: a possible link between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:727–739. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calegari VC, Torsoni AS, Vanzela EC, Araújo EP, Morari J, Zoppi CC, et al. Inflammation of the hypothalamus leads to defective pancreatic islet function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12870–12880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.173021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Kim HG. Cognitive dysfunctions in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2019;36(3):183–191. doi: 10.12701/yujm.2019.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan CM, Freed MI, Rood JA, Cobitz AR, Waterhouse BR, Strachan MW. Improving metabolic control leads to better working memory in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:345–351. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiwari BK, Pandey KB, Abidi AB, Rizvi SI. Markers of oxidative stress during diabetes mellitus. J Biomark. 2013;2013:378790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cziraki A, Lenkey Z, Sulyok E, Szokodi I, Koller A. L-arginine-nitric oxide-asymmetric dimethylarginine pathway and the coronary circulation: translation of basic science results to clinical practice. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:569914. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.569914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eftekharpour E, Fernyhough P. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction associated with peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021 doi: 10.1089/ars.2021.0152.Advanceonlinepublication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacCracken J, Hoel D. From ants to analogues. Puzzles and promises in diabetes management. Postgrad Med. 1997;101(4):138–150. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1997.04.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383:69–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60591-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020; accessible on: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html

- 19.Unnikrishnan R, Pradeepa R, Joshi SR, Mohan V. Type 2 diabetes: demystifying the global epidemic. Diabetes. 2017;66:1432–1442. doi: 10.2337/db16-0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnell RA, Carré JE, Affourtit C. Acute bioenergetic insulin sensitivity of skeletal muscle cells: ATP-demand-provoked glycolysis contributes to stimulation of ATP supply. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2022;30:101274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2022.101274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Sudha V, Unnikrishnan R, Bhansali A, Joshi SR, Joshi PP, Yajnik CS, Dhandhania VK, Nath LM, Das AK, Rao PV, Madhu SV, Shukla DK, Kaur T, Priya M, Nirmal E, Parvathi SJ, Subhashini S, Subashini R, Ali MK, Mohan V. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) in urban and rural India: Phase I results of the Indian Council of Medical Research–INdia DIABetes (ICMR–INDIAB) study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3022–3027. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJ, Feldman EL, Bril V, Freeman R, Malik RA, Sosenko JM, Ziegler D. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136–154. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavoie H, Gagnon J, Therrien M. ERK signalling: a master regulator of cell behaviour, life and fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(10):607–632. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, Hu X, Liu Y, Dong S, Wen Z, He W, Zhang S, Huang Q, Shi M. ROS signalling under metabolic stress: cross-talk between AMPK and AKT pathway. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0648-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen MC, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(4):2133–2223. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00063.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raposinho PD, Pedrazzini T, White RB, Palmiter RD, Aubert ML. Chronic neuropeptide Y infusion into the lateral ventricle induces sustained feeding and obesity in mice lacking either Npy1r or Npy5r expression. Endocrinology. 2004;145:304–310. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachsmuth HR, Weninger SN, Duca FA. Role of the gut-brain axis in energy and glucose metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54(4):377–392. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00677-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou XH, Sun LH, Yang W, Li BJ, Cui RJ. Potential role of insulin on the pathogenesis of depression. Cell Prolif. 2020;53(5):e12806. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhusal A, Rahman MH, Suk K. Hypothalamic inflammation in metabolic disorders and aging. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;79(1):32. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-04019-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Sun S, Wang X, Li Y, Zhu H, Zhang H, Deng A. A missense mutation in IRS1 is associated with the development of early-onset type 2 diabetes. Int J Endocrinol. 2020;2020:9569126. doi: 10.1155/2020/9569126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toyoshima Y, Nakamura K, Tokita R, Teramoto N, Sugihara H, Kato H, Yamanouchi K, Minami S. Disruption of insulin receptor substrate-2 impairs growth but not insulin function in rats. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(33):11914–11927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Tobe K, Yano W, Suzuki R, Ueki K, et al. Insulin receptor substrate 2 plays a crucial role in beta cells and the hypothalamus. J Clin Investig. 2004;114:917–927. doi: 10.1172/JCI21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W, Balland E, Cowley MA. Hypothalamic insulin resistance in obesity: effects on glucose homeostasis. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104(4):364–381. doi: 10.1159/000455865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wauman J, Zabeau L, Tavernier J. The leptin receptor complex: heavier than expected? Front Endocrinol. 2017;8:30. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossetti L, Giaccari A, DeFronzo RA. Glucose toxicity. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:610–630. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yagihashi S, Inaba W, Mizukami H. Dynamic pathology of islet endocrine cells in type 2 diabetes: β-cell growth, death, regeneration and their clinical implications. J Diabetes Invest. 2016;7(2):155–165. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roma LP, Jonas JC. Nutrient metabolism, subcellular redox state, and oxidative stress in pancreatic islets and β-cells. J Mol Biol. 2020;432(5):1461–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertacca A, Ciccarone A, Cecchetti P, Vianello B, Laurenza I, Maffei M, et al. 2005 Continually high insulin levels impair Akt phosphorylation and glucose transport in human myoblasts. Metab Clin Exp. 2005;54(12):1687–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catalano KJ, Maddux BA, Szary J, Youngren JF, Goldfine ID, Schaufele F. Insulin resistance induced by hyperinsulinemia coincides with a persistent alteration at the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase domain. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montagnani M, Chen H, Barr VA, Quon MJ. Insulin-stimulated activation of eNOS is independent of Ca2+ but requires phosphorylation by Akt at Ser(1179) J Biol Chem. 2001;276(32):30392–30398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King JR, Pescetelli N, Dehaene S. Brain mechanisms underlying the brief maintenance of seen and unseen sensory information. Neuron. 2016;92(5):1122–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong CX. Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J Pathol. 2011;225(1):54–62. doi: 10.1002/path.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson AR. Peripheral pathways to neurovascular unit dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:858429. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.858429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Lu F, Wang JZ, Gong CX. Concurrent alterations of O−GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of tau in mouse brains during fasting. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2078–2086. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gong CX, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Impaired brain glucose metabolism leads to Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration through a decrease in tau O−GlcNAcylation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:1–12. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2006-9101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu F, Shi J, Tanimukai H, Gu J, Gu J, Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. Reduced O−GlcNAcylation links lower brain glucose metabolism and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:1820–1832. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pritam P, Deka R, Bhardwaj A, Srivastava R, Kumar D, Jha AK, Jha NK, Villa C, Jha SK. Antioxidants in Alzheimer's disease: current therapeutic significance and future prospects. Biology. 2022;11(2):212. doi: 10.3390/biology11020212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dröge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(1):47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merry TL, Ristow M. Mitohormesis in exercise training. Free Radical Biol Med. 2016;98:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akash MSH, Rehman K, Chen S. Role of inflammatory mechanisms in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:525–531. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rehman K, Akash MS. Mechanisms of inflammatory responses and development of insulin resistance: how are they interlinked? J Biomed Sci. 2016;23(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0303-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krieger-Brauer HI, Kather H. Human fat cells possess a plasma membrane-bound H2O2-generating system that is activated by insulin via a mechanism bypassing the receptor kinase. J Clin Investig. 1992;89(3):1006–1013. doi: 10.1172/JCI115641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahadev K, Zilbering A, Zhu L, Goldstein BJ. Insulin stimulated hydrogen peroxide reversibly inhibits protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b in vivo and enhances the early insulin action cascade. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):21938–21942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holley CT, Duffy CM, Butterick TA, Long EK, Lindsey ME, Cabrera JA, et al. Expression of uncoupling protein-2 remains increased within hibernating myocardium despite successful coronary artery bypass grafting at 4 wk post-revascularization. J Surg Res. 2015;193(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prattichizzo F, De Nigris V, Mancuso E, Spiga R, Giuliani A, Matacchione G, et al. Short-term sustained hyperglycaemia fosters an archetypal senescence-associated secretory phenotype in endothelial cells and macrophages. Redox Biol. 2018;15:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rudich A, Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Khamaisi M, Bashan N. Lipoic acid protects against oxidative stress induced impairment in insulin stimulation of protein kinase B and glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetologia. 1999;42(8):949–957. doi: 10.1007/s001250051253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leto D, Saltiel AR. Regulation of glucose transport by insulin: traffic control of GLUT 4. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(6):383–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Withers DJ, Gutierrez JS, Towery H, Burks DJ, Ren JM, Previs S, et al. Disruption of IRS-2 causes type 2 diabetes in mice. Nature. 1998;391(6670):900–904. doi: 10.1038/36116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zick Y. Uncoupling insulin signalling by serine/threonine phosphorylation: a molecular basis for insulin resistance. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(5):812–816. doi: 10.1042/BST0320812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langlais P, Yi Z, Finlayson J, Luo M, Mapes R, De Filippis E, et al. Global IRS-1 phosphorylation analysis in insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2011;54(11):2878–2889. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tu W, Wang H, Li S, Liu Q, Sha H. The anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in chronic diseases. Aging Dis. 2019;10:637–651. doi: 10.14336/AD.2018.0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Watai Y, Tong KI, Shibata T, Uchida K, et al. Oxidative and electrophilic stresses activate Nrf2 through inhibition of ubiquitination activity of Keap1. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:221–229. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.221-229.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, Wakabayashi J, Maher J, Motohashi H, et al. Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 in determining Nrf2 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2758–2770. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01704-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang WX, Zhao ZR, Bai Y, Li YX, Gao XN, Zhang S, Sun YB. Sevoflurane preconditioning prevents acute renal injury caused by ischemia-reperfusion in mice via activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(4):303. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin CC, Yang CC, Chen YW, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. Arachidonic acid induces ARE/Nrf2-dependent heme oxygenase-1 transcription in rat brain astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:3328–3343. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0590-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tonelli C, Chio IIC, Tuveson DA. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;29:1727–1745. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dodson M, de la Vega MR, Cholanians AB, Schmidlin CJ, Chapman E, Zhang DD. Modulating NRF2 in disease: timing is everything. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;59:555–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pero RW, Roush GC, Markowitz MM, Miller DG. Oxidative stress, DNA repair, and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Detect Prev. 1990;14(5):555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mastrocola R, Restivo F, Vercellinatto I, Danni O, Brignardello E, Aragno M, Boccuzzi G. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in brain mitochondria of diabetic rats. J Endocrinol. 2005;187(1):37–44. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng Y, Liu J, Shi L, Tang Y, Gao D, Long J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction precedes depression of AMPK/AKT signaling in insulin resistance induced by high glucose in primary cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2016;137:701–713. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O'Dell TJ, Kandel ER, Grant SG. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus is blocked by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Nature. 1991;353(6344):558–560. doi: 10.1038/353558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gross NJ, Getz GS, Rabinowitz M. Apparent turnover of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid and mitochondrial phospholipids in the tissues of the rat. J Biol Chem. 1969;244(6):1552–1562. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)91795-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beckman JS. Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9(5):836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pieme CA, Tatangmo JA, Simo G, Biapa Nya PC, Ama Moor VJ, Moukette Moukette B, et al. Relationship between hyperglycemia, antioxidant capacity and some enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in African patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fiorello ML, Treweeke AT, Macfarlane DP, Megson IL. Intermittent exposure of cultured endothelial cells to physiologically relevant fructose concentrations has a profound impact on nitric oxide production and bioenergetics. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0267675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357(Pt 3):593–615. doi: 10.1042/bj3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Król M, Kepinska M. Human nitric oxide synthase-its functions, polymorphisms, and inhibitors in the context of inflammation, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):56. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Markwardt ML, Nkobena A, Ding SY, Rizzo MA. Association with nitric oxide synthase on insulin secretory granules regulates glucokinase protein levels. Mol Endocrinol (Baltimore, MD) 2012;26(9):1617–1629. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kellogg DL, McCammon KM, Hinchee-Rodriguez KS. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase mediates insulin- and oxidative stress-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle myotubes. Free Radical Biol Med. 2017;110:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McConell GK, Rattigan S, Lee-Young RS, Wadley GD, Merry TL. Skeletal muscle nitric oxide signaling and exercise: a focus on glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(3):E301–E307. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00667.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu Q, Xia Z, Liong EC, Tipoe GL. Chronic aerobic exercise improves insulin sensitivity and modulates Nrf2 and NF-κB/IκBα pathways in the skeletal muscle of rats fed with a high fat diet. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20(6):4963–4972. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lewis RE, Cao L, Perregaux D, Czech MP. Threonine 1336 of the human insulin receptor is a major target for phosphorylation by protein kinase C. Biochemistry. 1990;29(7):1807–1813. doi: 10.1021/bi00459a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee SH, Park SY, Choi CS. Insulin resistance: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46(1):15–37. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2021.0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yarahmadi A, Azarpira N, Mostafavi-Pour Z. Role of mTOR complex 1 signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of diabetes complications: a mini review. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2021;10(3):181–189. doi: 10.22088/IJMCM.BUMS.10.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ramdani G, Schall N, Kalyanaraman H, Wahwah N, Moheize S, Lee JJ, Sah RL, Pfeifer A, Casteel DE, Pilz RB. cGMP-dependent protein kinase-2 regulates bone mass and prevents diabetic bone loss. J Endocrinol. 2018;238(3):203–219. doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu YW, Zhu X, Zhang L, Lu Q, Zhang F, Guo H, et al. Cerebroprotective effects of ibuprofen on diabetic encephalopathy in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;117:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C, Zlokovic BV. Establishment and dysfunction of the blood–brain barrier. Cell. 2015;163(5):1064–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li T, Cao HX, Ke D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus easily develops into Alzheimer's disease via hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41(6):1165–1171. doi: 10.1007/s11596-021-2467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lacy ME, Moran C, Gilsanz P, Beeri MS, Karter AJ, Whitmer RA. Comparison of cognitive function in older adults with type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and no diabetes: results from the Study of Longevity in Diabetes (SOLID) BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2022;10(2):e002557. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jacobson AM, Ryan CM, Cleary PA, Waberski BH, Weinger K, Musen G, et al. Biomedical risk factors for decreased cognitive functioning in type 1 diabetes: an 18 year follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) cohort. Diabetologia. 2011;54:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1883-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hudson JL, Bundy C, Coventry PA, Dickens C. Exploring the relationship between cognitive illness representations and poor emotional health and their combined association with diabetes self-care. A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Antenor-Dorsey JA, Meyer E, Rutlin J, Perantie DC, White NH, Arbelaez AM, et al. White matter microstructural integrity in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:581–589. doi: 10.2337/db12-0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:661–666. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuźma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, Levine DA, Ukoumunne OC, Llewellyn DJ. Stroke and dementia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2018;14(11):1416–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Singh S, Trigun SK. Activation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in cerebellum of chronic hepatic encephalopathy rats is associated with up-regulation of NADPH-producing pathway. Cerebellum (Lond Engl) 2010;9(3):384–397. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0172-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Magistretti PJ, Allaman I. Lactate in the brain: from metabolic end-product to signalling molecule. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(4):235–249. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu S, Stein RA, Yoshioka C, Lee CH, Goehring A, Mchaourab HS, et al. Mechanism of NMDA receptor inhibition and activation. Cell. 2016;165(3):704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Paoletti P, Bellone C, Zhou Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(6):383–400. doi: 10.1038/nrn3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lampron A, ElAli A, Rivest S. Innate immunity in the CNS: redefining the relationship between the CNS and its environment. Neuron. 2013;78(2):214–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Annachiara C, David JB, Angus MK, Roger NG, Myers R, Federico ET, Terry J, Richard BB. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):0140–6763. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dimitrios D, Jae KR, Mario M, Kim MB, Le Natacha M, Mark AP, Thomas JD, Dimitri SS, Catherine B, Hiroyuki H, Sara GM, Jennie BL, Hans L, Jay LD, Mark HE, Katerina A. Fibrinogen-induced perivascular microglial clustering is required for the development of axonal damage in neuroinflammation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1227. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Beynon SB, Walker FR. Microglial activation in the injured and healthy brain: What are we really talking about? Practical and theoretical issues associated with the measurement of changes in microglial morphology. Neuroscience. 2012;225:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]