Abstract

Cyanobacteria are ancestors of chloroplast and perform oxygen-evolving photosynthesis similar to higher plants and algae. However, an obligatory requirement of photons for their growth results in the exposure of cyanobacteria to varying light conditions. Therefore, the light environment could act as a signal to drive the developmental processes, in addition to photosynthesis, in cyanobacteria. These Gram-negative prokaryotes exhibit characteristic light-dependent developmental processes that maximize their fitness and resource utilization. The development occurring in response to radiance (photomorphogenesis) involves fine-tuning cellular physiology, morphology and metabolism. The best-studied example of cyanobacterial photomorphogenesis is chromatic acclimation (CA), which allows a selected number of cyanobacteria to tailor their light-harvesting antenna called phycobilisome (PBS). The tailoring of PBS under existing wavelengths and abundance of light gives an advantage to cyanobacteria over another photoautotroph. In this work, we will provide a comprehensive update on light-sensing, molecular signaling and signal cascades found in cyanobacteria. We also include recent developments made in other aspects of CA, such as mechanistic insights into changes in the size and shape of cells, filaments and carboxysomes.

Keywords: Gene regulation, Morphogenes, Photosensor, Reactive oxygen species, Response regulators, Signaling cascade

Introduction

Cyanobacteria are critical for nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration through nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis (Behrenfeld et al. 2006; Beardall et al. 2009; Glass et al. 2015). These Gram-negative prokaryotes are ancestors of the chloroplast of higher plants and possess photosynthetic machinery that produces oxygen similar to algae and plants. Cyanobacteria have been used to understand the process of photosynthesis, iron and redox homeostasis, nitrogen fixation and heterocyst development (Kumar et al. 2010; Peleato et al. 2016). These organisms can also be used for the production of nanoparticles, bioenergy and economically significant molecules in a carbon–neutral manner (Sánchez-Baracaldo et al. 2022; Maurya and Kumar 2022).

During photosynthesis, all photoautotrophs adjust their photosynthetic machinery and other developmental processes to maximize overall fitness in dynamic light environments (Montgomery 2016). The morphological change that occurs as a result of exposure to light signals is called photomorphogenesis. Almost all photosynthetic organisms have unique characteristics to perceive changes in the color and intensity of light to program their development to increase their ability to utilize available light resources (Chen et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2010; Sanfilippo et al. 2019; Jing and Lin 2020). The change in color and intensity of light in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems occurs due to plant canopy coverage or due to the existence of photosynthetic organisms in the upper layer of aquatic habitat. Also, the presence of dissolved organic matter in a water column significantly alters the spectral property (Postius et al. 2001; Babin and Stramski 2003). For example, smaller plants growing under the canopy of big plants experience a low light environment similar to the organisms present at higher depths in the aquatic habitat. On the surface of an aquatic ecosystem or at the upper surface of a plant, a high-intensity radiance rich in red wavelengths is available, whereas in a benthic region or under the canopy, a low light environment rich in green wavelengths exists (Postius et al. 2001).

The change in available light resources occurs due to the utilization of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR; 400–700 nm), mainly in the blue and red region, at the upper surface of the plant canopy/water column (Postius et al. 2001; Babin and Stramski 2003). Therefore, plants growing under the canopy or benthic photosynthetic organisms need to adjust their photosynthetic machinery and developmental processes in response to available light signals to maximize their growth and survival. To perceive light signals, photosynthetic organisms, including cyanobacteria, possess a wide range of photosensor proteins (Cashmore et al. 1999; Montgomery and Lagarias 2002; Chen et al. 2004; Schepens et al. 2004; Montgomery 2007; Villafani et al. 2020). In plants, various light-dependent processes such as seedling germination, phototropism, circadian rhythms, chloroplast and stomatal movements, shade avoidance, stress response and flowering time have been investigated in detail (Cashmore et al. 1999; Schepens et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2004; Jing and Lin 2020). However, for the present work, the effect of radiation on the growth and development of plants is not included here, which is otherwise well-studied.

Similar to plants, cyanobacteria respond to fluctuation in light environments and adjust their growth and development program to ensure their best performance (Sanfilippo et al. 2019). Chromatic acclimation (CA) is a well-studied light-dependent developmental process in cyanobacteria where several cyanobacteria can change the composition of their major light-sequestering antenna called phycobilisome (Bennett and Bogorad 1973; Kehoe and Gutu 2006; Singh et al. 2010). The light-dependent change in light antenna complex and morphology are well studied in a cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon which is a well-established model organism to study CA (Montgomery 2015). Here, we present different light-dependent responses, photoreceptors and signaling cascades used by cyanobacteria to interact with the ambient light environment. We also present developments made in the understanding of the molecular mechanism of CA and light-dependent photoregulation of morphology in Fremyella diplosiphon (F. diplosiphon). In this review, we focus on F. diplosiphon which is a freshwater filamentous cyanobacterium and its 9.96 Mbp genome encodes more than 300 proteins related to a two-component signaling cascade and 27 phytochrome-related proteins for perceiving light signals (Yerrapragada et al. 2015). In addition to CA, light-dependent regulation of the size and shape of cells, filament length and carboxysome biogenesis has been well-studied in F. diplosiphon.

Light-dependent responses in cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria show acclimation and/or adaptation to changing light conditions. Several cyanobacteria can alter their photosynthetic pigments according to the color of light (Everroad et al. 2006; Kehoe and Gutu 2006). Acclimation to light was first noticed in 1883 and 1902 (Engelmann 1883, 1902). CA is best studied in the filamentous cyanobacterium F. diplosiphon, whose cells are bluish-green under a red light (RL) enriched environment and red under green light (GL) enriched growth environment. This alteration in the color of an organism by light is due to a change in the pigment of its main light-harvesting antenna called phycobilisome (Bordowitz and Montgomery 2008; Kumar et al. 2019; Maurya and Kumar 2022). CA is found in three forms in different species of cyanobacteria. In group I CA, species produce both phycoerythrin (PE; λmax ~ 565 nm) and phycocyanin (PC; λmax ~ 620 nm) but do not change the amount of these phycobiliproteins (PBPs) under changing light conditions. Group II CA involves an increase in cellular PE levels in response to growth in GL, but there is no change in PC levels. Finally, group III CA is characterized by an alteration in both PC and PE levels by the perceived color of light. The filamentous cyanobacterium F. diplosiphon UTEX 481 (also known by other names such as Calothrix or Tolypothrix sp. PCC 7601) is used as a model system to study group III CA to investigate the light quality-dependent regulation of the production of PBPs as well as photomorphogenic responses (Bennett and Bogorad 1973; Singh and Montgomery 2015; Montgomery 2022).

F. diplosiphon shows a differential incorporation of PBPs in phycobilisome (PBS) during growth in GL- and RL- enriched light environments (Gutu and Kehoe 2012). The red versus green wavelengths varies greatly at a different distance in a water column; therefore, CA-dependent change in PBS pigment composition gives benefit to CA-exhibiting cyanobacteria over other photoautotrophs (Campbell 1996; Postius et al. 2001). CA involves sensing of light which is achieved by a phytochrome-related photoreceptor called RcaE in F. diplosiphon (Kehoe and Grossman 1996). Apart from the change in pigmentation during CA, there are prominent changes in the size and shape of cells and filaments to maximize the photosynthetic performance of the organism (Montgomery 2015). These light signal-dependent morphological changes (photomorphogenesis) together with alteration in the composition of PBS increase the overall fitness of the organism under a dynamic light environment (Pattanaik et al. 2012; Singh and Montgomery 2012; Walters et al. 2013; Montgomery 2015).

In addition to the quality of light, the intensity of light also influences morphology in cyanobacteria. Trichomes of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii are longer under low-light conditions (Bittencourt-Oliveira et al. 2012). Whereas, in F. diplosiphon, high light causes induction of increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which is linked with spherical cell morphology, but in contrast, elongated cells with low levels of ROS are observed under lower light intensity (Pattanaik et al. 2012; Singh and Montgomery 2012; Singh et al. 2013; Walters et al. 2013). Thus, F. diplosiphon can modulate cell morphology under varying light conditions to accommodate the thylakoid membrane.

Cyanobacterial movement is affected by different wavelengths and intensities of light in a process called phototaxis. Similarly, different biological processes such as avoidance of exposure to high light, reorganization of photosystem, and gliding, phototactic and phototaxis movements are affected by UV-A (315–400 nm) radiation in number of cyanobacteria (Bebout and Garcia-Pichel 1995; Campbell et al. 1998; Khayatan et al. 2015; Yoshihara and Ikeuchi 2004; Song et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2018). Cyanobacteria have several methyl-accepting called transducer-like proteins that are responsible for taxis movement (Yoshihara et al. 2004; Ishizuka et al. 2006; Narikawa et al. 2008).

A putative UV-B (280–315 nm) photoreceptor has been proposed in a cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis PCC 6912 for the UV-B-dependent production of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) (Portwich and Garcia-Pichel 2000). Also, the influence of UV-B can control growth and development in cyanobacteria, in addition to the induction of MAAs (Jenkins 2009). Notably, MAA and scytonemin are UV-absorbing compounds, and their induction in several cyanobacteria is an acclimation response to UV radiation (280–400 nm) (Singh et al. 2010). Based on action spectra of MAAs biosynthesis, a reduced pterin has been proposed as a photoreceptor for the induction of MAAs in cyanobacteria (Portwich and Garcia-Pichel 2000). The proposition for the participation of reduced pterin in MAAs synthesis is supported by the experiment that involves the addition of a pterin inhibitor to the growth medium during the induction of MAAs by UV-B. The inhibition of pterin biosynthesis also hampers the biosynthesis of MAAs (Portwich and Garcia-Pichel 2000). However, care should be taken during the interpretation of the data obtained from such studies as inhibitors could affect MAAs biosynthesis due to their negative effect on photosynthesis (Singh et al. 2014).

Similar to higher plants, cyanobacteria show acclimation to red and far-red light (Gan and Bryant 2015; Liu et al. 2023). The acclimation to red/far-red light in cyanobacteria is mediated by a red/far-red photoreceptor, RfpA, and its response regulators RfpB and RfpC (Gan and Bryant 2015). Generally, cyanobacteria only contain chlorophyll α as a light-harvesting pigment in addition to phycobiliproteins; however, recent studies have shown that not all but a few cyanobacteria can produce far-red light-absorbing chlorophylls d and f pigments (Zhao et al. 2015; Mascoli et al. 2022; Gisriel and Elias 2023).

Light-mediated signaling cascade

Cyanobacteria encode a vast array of sensory proteins that allow them to monitor changes in the light environment (Ikeuchi and Ishizuka 2008; Rockwell et al. 2014). The diurnal and seasonal changes in the light environment include alterations in the intensity, quality, direction and duration of light that affect the overall developmental processes and fitness of photosynthetic organisms. In response to a light signal, the sensory proteins sense the signals, transmit the perceived signals, and finally result in a specific cellular response. In cyanobacteria, the signaling cascade involves the phosphorylation of other proteins using two-component systems similar to the phytochrome-dependent signaling in algae and plants (Schepens et al. 2004; Jing and Lin 2020). Sensor histidine kinase and response regulators are two components of the signal transduction pathway (Stock et al. 2000; Mascher et al. 2006). In cyanobacteria, photoreceptors can sense different light environments to regulate physiological and developmental processes (Fig. 1) (Montgomery 2007; Gan and Bryant 2015; Bhaya 2016; Wang and Chen 2022).

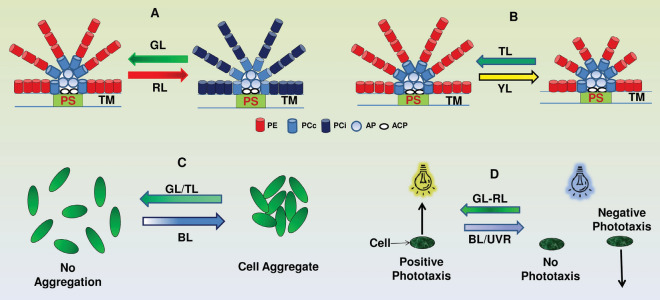

Fig. 1.

Light-dependent physiological responses regulated by phytochrome-related photoreceptors in cyanobacteria. A and B Chromatic acclimation in cyanobacteria showing light signal-dependent change in photosynthetic light-harvesting antenna complex called phycobilisome (PBS). The photosynthetic reaction centers (shown in green) receive light energy from the PBS attached to the thylakoid membrane (TM). The ratio of phycocyanin (PC) and phycoerythrin (PE) changes in the outer rod region during type III chromatic acclimation (CA3). RcaE, a member of the phytochrome superfamily photoreceptors controls levels of PE and PC in response to green (GL) and red light (RL). Another photoreceptor, DpxA, controls the PE levels in the PBS and represses PE production in yellow light, and raises PE levels in the outer rod region in teal light (TL). C The phytochrome superfamily photoreceptors SesA, SesB and SesC are involved in the induction of cell aggregation by blue light (BL) and reversal of aggregation by green and teal light. D The regulation of phototaxis towards the light source (positive phototaxis) or away from light (negative phototaxis) is caused by three photoreceptors Cph2, SyPixJ1, UirS of the phytochrome superfamily. Black arrows depict the direction in which cells are moving in reference to the light source. Cells do not show any phototaxis or negative phototaxis in response to blue or ultraviolet light. On exposure to BL, Cph2 generates cyclic di-guanosine monophosphate (c- di-GMP), which inhibits type IV pilus-based motility (color figure online)

Photosignal receptors/photosensors in cyanobacteria

In cyanobacteria, the best studied light-sensing photo-switches are bilin-based photoreceptors that include phytochrome-related photoreceptors such as cyanobacteriochromes (CBCRs), blue light (BL) photosensors, rhodopsins, UV receptors and flavin-binding proteins (Hwang et al. 2019; Rockwell and Lagarias 2020; Priyadarshini et al. 2023) (Table 1). Once a light signal is perceived by these photoreceptors, light information from the environment is transmitted downstream by the below-mentioned response regulators and/or second messengers. In the following sections, different photoreceptors (Table 1) found in cyanobacteria are discussed.

Table 1.

Cyanobacterial photoreceptors, associated effectors, and their light quality-dependent responses

| Light quality | Photoreceptors | Effectors | Response | Organism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red/Green | RcaE | RcaF |

Chromatic acclimation, Cellular morphology, Filament length, Reactive oxygen Species, Structural proteins of carboxysome |

Fremyella diplosiphon | Kehoe and Grossman (1996), (1997), Terauchi and Ohmori (2004), Singh and Montgomery (2014), (2015), Busch and Montgomery (2015), Rohnke et al. (2018) |

| RcaC | |||||

| CpeR | |||||

| BolA | |||||

| MreB, MreC, MreD | |||||

| TspO | |||||

| CcaS | CcaR | Pigmentation |

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133 |

Hirose et al. (2008), (2010), (2013), Hirose et al. (2010) | |

| Red/Far-red | Cph1 | Rcp1 | Growth/fitness | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Fiedler et al. (2004) |

| RfpA | RfpB, RfpC | Pigmentation | Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 9212 | Gan et al. (2014), Gan and Bryant (2015), Zhao et al. (2015) | |

| AphC | CyaC | Motility | Anabaena cylindrica, Anabaea sp. PCC 7120 | Ohmori et al. (2002), Okamoto et al. (2004) | |

| Blue/Green | PixJ/TaxD1 | – | Phototaxis | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Yoshihara et al. (2000), (2004), (2006), Bhaya et al. (2001), Ng et al. (2003) |

| Cph2 | Intragenic effector domain | Phototaxis, growth/fitness | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Fiedler et al. (2004), Moon et al. (2011) | |

| SesA | Intragenic effector domain | Cellular aggregation | Thermosynechococcus elongatus | Enomoto et al. (2014), (2015) | |

| SesC | Intragenic effector domain | Cellular aggregation | Thermosynechococcus elongatus | Enomoto et al. (2015) | |

| UV-A/B/C | PixA/UirS | NixB/UirR, NixC/LsiR | Phototaxis | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Narikawa et al. (2011), Song et al. (2011) |

| Teal/Yellow | DpxA | – | Pigmentation | Fremyella diplosiphon | Wiltbank and Kehoe (2016) |

| Blue/Teal | SesB | Intragenic effector domain | Cellular aggregation | Thermosynechococcus elongatus | Enomoto et al. (2015) |

| Blue | PipA | – | Growth | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Wilde et al. (1997) |

| White | PtxD | – | Phototaxis of hormogonium | Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133 | Campbell et al. (2015) |

‘–’ not known.

Phytochrome-class photoreceptors

The phytochrome was first discovered in plants and contains both a light-sensory domain and an effector (signaling) domain. The sensory domain of phytochrome binds a bilin chromophore that undergoes light-dependent conformational changes to alter the activity of the effector domain (Butler et al. 1959; Kehoe and Grossman 1996). Several phytochrome-like photosensor proteins are found in cyanobacteria and other prokaryotes that regulate different light-dependent biological processes (Table 1) (Rockwell et al. 2011; Wiltbank and Kehoe 2016). The N-terminal region of these proteins contains different types of photosensory modules like PAS-GAF-PHY, GAF-GAF, or GAF-PHY, and binds a bilin chromophore (Wagner et al. 2005; Burgie et al. 2014). The C-terminal region shows similarity to the output domain of histidine kinases (Buchberger and Lamparter 2015). Cyanobacteriochromes (CBCRs) are comprised of different domains that can sense different colors of light to transmit perceived signals to carry out different developmental processes (Fushimi and Narikawa 2019; Villafani et al. 2020). These domains have a vast range of abilities to sense different wavelengths (Rockwell and Lagarias 2017). Thus, photoreceptors act as a switch to control different outputs in response to changes in the ratio of two colors perceived by their chromophore (Anders et al. 2013). The output domain of phytochrome superfamily members contains MCP, GGDEF, EAL, and histidine kinase domains having recognized functions (Wiltbank and Kehoe 2019).

Blue light photoreceptors

Several BL photoreceptors such as cryptochromes, phototropins and BLUF (blue light using FAD) domain photosensors are found in cyanobacteria (Montgomery 2007; Masuda 2013). Cryptochromes are similar to photolyases of prokaryotes that are involved in DNA damage repair (Brudler et al. 2003). The prokaryotic phototropin proteins have a LOV (light/oxygen/voltage) domain which is a member of the PAS (Per/Arnt/Sim) domain family. Also, the LOV domain uses FMN as a chromophore (Losi et al. 2002; Taylor and Zhulin 1999; Crosson et al. 2003).

Another class of BL photosensors has conserved BLUF domain. BLUF domain-containing proteins in cyanobacteria are linked to GGDEF and EAL domains (Fiedler et al. 2004; Okajima et al. 2006; Nakasone et al. 2023). In Synechocystis sp., the BLUF protein, i.e., PixD, controls positive phototaxis under white light or illumination of 500–700 nm wavelengths of light (Masuda et al. 2004; Okajima et al. 2006).

UVR receptors

The irradiance of different wavelengths of UV light can act as a stressor or photo-regulatory signal to impact the overall fitness and development of cyanobacteria (Singh et al 2010, 2023; Rockwell and Lagarias 2010). Emerging evidence indicates the role of pterins during growth under UVR (Sinha et al. 2001; Xue et al. 2005). However, UV sensor protein, namely UirS (UV intensity response sensor) and its cognate response regulator UirR (UV intensity response regulator) regulate UV-A radiation-dependent processes in cyanobacteria (Rockwell and Lagarias 2010; Song et al. 2011). UirS is known to mediate UV-A-dependent responses by controlling the expression of transcription activator LsiR (light and stress integrating response regulator) via UirR. On sensing the UV signal, membrane-bound UirS phosphorylates UirR, which in turn binds to the promoter sequence of LsiR and positively controls the transcription of its downstream coding sequence (Song et al. 2011). UirS is a phytochrome-related cyanobacteriochrome that has a GAF domain with highly conserved cysteine residues for the attachment of the phycocyanobilin (PCB) chromophore (Rockwell and Lagarias 2010; Song et al. 2011). The GAF domain acts as a primary UV-A photoreceptor for UV-A radiation-dependent responses in cyanobacteria (Song et al. 2011).

Rhodopsin

A membrane-bound photochromic 14 KDa rhodopsin protein has been reported in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 which acts as a sensor of GL (Jung et al. 2003). Based on detailed biochemical analysis, it was found that cyanobacterial rhodopsin photosensors exist in two stable isoforms that are interconvertible by 549 nm and 537 nm wavelengths of light (Vogeley et al. 2004; Sineshchekov et al. 2005). This suggests that rhodopsin, similar to the phytochromes, may act as a light-dependent regulator for controlling the expression of genes in cyanobacteria. Also, the binding of rhodopsin to a light-harvesting carotenoid antenna has been proposed in Gloeobacter violaceus that helps in the absorption of light for photosynthesis (Chazan et al. 2023; Chuon et al. 2023; Imasheva et al. 2009).

Signal transduction through response regulators and second messengers

Several transcriptional regulators that work under the control of photosensor proteins are known in prokaryotes (Galperin 2006). Such transcriptional regulators are called Response Regulators (RRs). These RRs contain different types and combinations of domains, such as KEGG, SENTRA, COG, GGDEF and EAL (Romling et al. 2005; Galperin 2006). Similar to eubacteria, cyanobacterial RRs function in classical two-component cascades and/or chemotaxis cascades. Cyanobacterial RRs possess domains that either act as transcription factors or possess enzymatic activity. These RRs are also known to modulate the activity of other proteins by interacting with their target protein activity (Galperin 2006). These regulators are activated by the environmental signals sensed by the sensors and modulate the function of the different domains of the same protein or completely new protein via phosphorylation or c-di-GMP second messenger (Fig. 2) (West and Stock 2001; Romling et al. 2005; Enomoto et al. 2023).

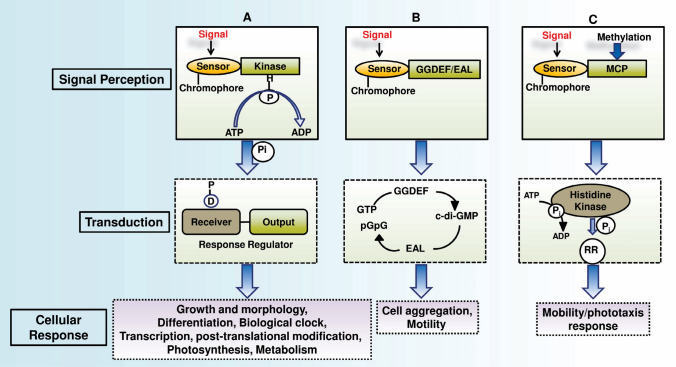

Fig. 2.

Light signal-dependent signaling cascade and cellular responses in cyanobacteria. A ATP-dependent kinases are part of photosensors and initiate phosphorelay cascades in response to light signals. Light-dependent phosphorelay involves the transfer of a phosphate group to a response regulator (RR) during the transmission of the light signal. The activation of RR in response to a light-signaling cascade causes different cellular responses. B Several photosensors utilize GGDEF and EAL domains as output components that are involved in the bis-(3′, 5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) cycle. GGDEF activity causes c-di-GMP production from GTP and EAL activity produces diguanylate (pGpG) from c-di-GMP. C In some cases, cyanobacteria use methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein domains (MCP) as output components for the perception of light signals. Light absorption by the sensor domain causes reversible methylation of the MCP domain and the signal is further transmitted by controlling the activity of histidine kinases and RRs to affect cellular processes. P, phosphorylation; Pi, inorganic phosphate; H, histidine residue; D, aspartate residue. The figure was redrawn using information given in Montgomery (2007) (color figure online)

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) and calcium are another class of second messengers that manage light-dependent responses in cyanobacteria (Mantovani et al. 2023). In Anabaena cylindrica, cAMP regulates red/far-red light-dependent photoresponses while calcium regulates the photoorientation of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Moon et al. 2004; Ohmori et al. 2002; Okamoto et al. 2004). The c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP are reported to control phototactic responses (Figs. 1 and 2) and repair photosystem (PS) II, respectively, during the growth of cyanobacteria under UV-radiation (Terauchi and Ohmori 2004; Jenkins 2009; Hengge 2009). The second messengers also mediate cellular differentiation and heterocyst formation during nitrogen starvation (Neunuebel and Golden 2008; Agostoni and Montgomery 2014; Enomoto et al. 2023). The abovementioned findings are supported by the fact that light signals play an important role in controlling the cellular levels of cAMP and c-di-GMP in cyanobacteria (Agostoni et al. 2013; Ohmori et al. 2002; Ohmori and Okamoto 2004; Okamoto et al. 2004; Terauchi and Ohmori 2004.)

Light-dependent induction of ROS is associated with transcriptional changes of several genes in cyanobacteria. However, small amounts of ROS are also generated by the electron transport chain of photosynthesis and respiration (He and Häder 2002; Castenholz and Garcia-Pichel 2012). In addition, cyanobacteria can also sense seasonal changes in day length to adjust their cellular activities. The circadian clock-regulating genes are identified in S. elongatus PCC 7942. Regulation of promoters in a time-specific manner causes diurnal changes in cell division, energy metabolism, and structural changes of chromosomes (Chavan and Swan 2021). The kaiA, kaiB and kaiC (kaiABC) genes code proteins that constitute the core components of the cyanobacterial circadian clock, and CikA (circadian input kinase A) sense the diurnal change in the redox state of the quinone pool (Fang et al. 2023).

Molecular composition of phycobilisome and mechanism of CA

The PBS consists of a core and rods, and rods originate from the core. The core and rods of PBS are constituted by three types of chromophore carrying PBPs—PE, PC, and allophycocyanin (AP; λmax ~ 650 nm) (Bennett and Bogorad 1973; de Marsac and Cohen-Bazire 1977). Several units of the above three PBPs are interconnected with each other via linker proteins to constitute a three-dimensional hemidiscoidal PBS that remains connected to the outer surface of thylakoids at the site of PSII through anchor proteins (de Marsac 1983; Federspiel and Grossman 1990; Federspiel and Scott 1992) (Fig. 1). However, under a fluctuating light-quality environment, the PBSs can transfer harvested excitation energy to both PSII and PSI for maintaining a sustainable electron flow between two photosystems. This phenomenon of balanced excitation of both PSII and PSI by PBSs is called state transitions which is regulated by the redox state of plastoquinone (PQ) (Calzadilla and Kirilovsky 2020; McConnell et al. 2002; Maurya et al. 2023). The preferential excitation of PSII (state II) causes a reduction (gain of electron) of the PQ-pool and reduced PQ-pool signals attachment of PBS to PSI (state I). Similarly, over-excitation of PSI results in the accumulation of oxidized PQ that triggers state II transition (Lamb et al. 2018; Calzadilla and Kirilovsky 2020). Thus, the association of PBSs with PSII or PSI during state transition permits the proper functioning of two photosystems under dynamic light conditions.

In addition to the quality of light, the high intensity of light saturates the entire photosynthetic Z-scheme and can cause damage to photosystems. To overcome this problem, cyanobacteria use a photoactive Orange Carotenoid Protein (OCP)-dependent photoprotective mechanism that results in Non-Photochemical-Quencing (NPQ) of surplus radiant energy absorbed by PBSs. The active form of OCP interacts with PBSs and provides photoprotection to photosynthetic reaction centers by dissipating excess absorbed radiation as heat under a high-light environment (Calzadilla and Kirilovsky 2020; Chukhutsina and van Thor 2022; Domínguez-Martín et al. 2022; Muzzopapa and Kirilovsky 2020; Stadnichuk and Krasilnikov 2023). Thus, both state transitions and OCP-mediated NPQ ensure the proper functioning of PBSs in cyanobacteria.

The α and β subunits of AP are encoded by the apcA1B1 genes and constitute the core part of the PBS (Conley et al. 1986; Houmard et al. 1988). The genes apcC and apcE are found in close association with apcA1B1 genes in the genome of F. diplosiphon. The apcC gene code core-linker protein while the apcE code core-membrane linker protein (Houmard et al. 1990). Both apcC and apcE gene products attach core to the thylakoid membrane and their transcript and protein levels are not altered considerably during CA (Houmard et al. 1990). This suggests that products of these two genes are equally abundant in GL- and RL- growth conditions. The core-proximal part of each rod always consists of a “constitutive PC” (PCc or PC1) which is coded by cpcB1A1 genes (Conley et al. 1988). In contrast, the core-distal part of the rods is the site of alteration during CA in cyanobacterial species. The core-distal end of the rod is made up of GL- absorbing PE under a low-light environment having excess photons of green wavelengths, and the cpeBA operon is responsible for the production of β and α subunits of PE. The PE linkers are encoded by the cpeCDE operon that connects PE subunits with each other as well as to the core proximal part of the rod (Rosinski et al. 1981; Mazel et al. 1986). The expression of cpeBA and cpeCDE operons is activated by the GL in F. diplosiphon even though the two operons are not physically connected in the genome (Federspiel and Scott 1992). Conversely, the core-distal end of rods of PBS contains an “inducible PC” (PCi or PC2) during growth under an RL-enriched high-light environment (Conley et al. 1985, 1988). The cpcB2A2 operon produces β and α subunits of PCi while the cpcH2I2D2 operon is responsible for the production of three linker proteins (Fig. 3). The abovementioned two operons are collectively called “cpc2”, and are transcribed at the same time by RL (Conley et al. 1985, 1988; Montgomery 2007).

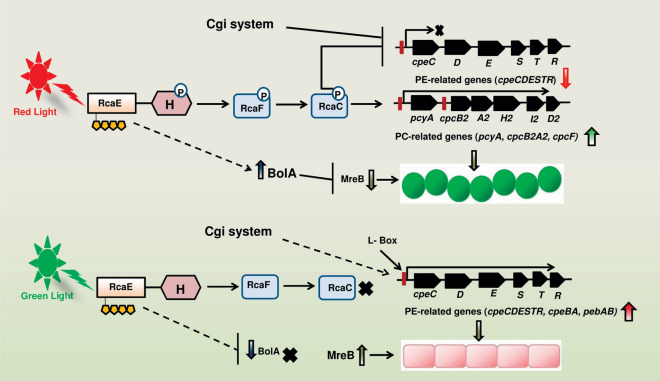

Fig. 3.

Regulation of pigmentation and morphology during chromatic acclimation (CA) by phytochrome-related photosensor protein RcaE and Cgi system. A complex interaction between photoreceptor and downstream response regulators (RRs) in response to green light (GL) and red light (RL) signals causes CA in Fremyella diplosiphon. Photoreceptor RcaE with an attached bilin chromophore (gold pentagon) in the light-sensing domain (rectangle) and a two-component histidine (H) output domain (hexagon). In RL, RcaE acts as a kinase, and in GL, it acts as a phosphatase. In RL, RcaE phosphorylates the response regulator RcaF, which then phosphorylates RcaC (a transcriptional regulator). The kinase activity of RcaE under RL results in greater binding of phosphorylated RcaC to L-boxes. The binding of active RcaC results in the expression of PC-related genes (pcyA, cpc2) and simultaneous inhibition of PE-related genes (cpeCDESTR). In GL, RcaE has phosphatase activity and causes dephosphorylation of RcaF and results in the accumulation of unphosphorylated RcaC in the cell. The inactive form of RcaC can not bind to L-boxes and therefore results in the downregulation of PC-related genes and activation of genes required for PE accumulation. The Cgi system contributes to CA regulation by further repressing the expression of the cpeCDESTR in RL. In GL, the Cgi system may slightly enhance the expression of cpeCDESTR operon (indicated by the dashed line). RcaE also controls cellular morphology during CA via an unknown signaling cascade that does not involve RcaF and RcaC. RcaE is required for the differential accumulation of BolA protein under GL and RL. Higher accumulation of BolA due to higher gene transcription under RL causes lower accumulation of MreB due to the downregulation of its encoding gene. This results in spherical morphology under RL. However, lower accumulation of BolA under GL results in higher accumulation of MreB and rod shaped morphology of cells. P represents phosphorylation

Several light-responsive genes other than those involved in CA are reported in F. diplosiphon (Alvey et al. 2003; Pattanaik et al. 2014; Rohnke et al. 2018). The expression of these genes is significantly different in RL- and GL-acclimated cells. CpeR and RcaE are activator and regulator proteins, respectively, that are required for the accumulation of functional PBSs in the cell (Cobley et al. 2002; Seib and Kehoe 2002). CpeR and RcaE act as GL- and RL- responsive regulators and activate the biosynthesis of PE and PC. Therefore, these proteins enable the organism to use GL or RL for its growth (Cobley and Miranda 1983; de Marsac 1983). A cpeF is a bilin lyase-encoding gene of F. diplosiphon that is required for post-translational modification of PE to enable its incorporation into a PBS (Kronfel et al. 2019).

The changes that take place in the structure of PBS have a major impact on F. diplosiphon cells during CA. These changes, which predominantly take place at the level of transcription of genes encoding PCi and PE structural units, lead to the remodeling of PBS to efficiently harvest available photons of light for photosynthesis (Gendel et al. 1979; Oelmüller et al. 1988; Casey and Grossman 1994). The expression pattern of PBS components encoding genes changes in hours, while the structural change in PBS takes several days after shifting GL-acclimated cultures to RL-environment (Bennett and Bogorad 1973; Oelmüller et al. 1988; Singh and Montgomery 2011).

Two independent pathways have gained attention in F. diplosiphon for the biosynthesis of PBPs in response to light signals during CA. The first well-established pathway is called the Regulator of Chromatic Acclimation (Rca) system. The Rca system is vital for the induction of PC and simultaneous inhibition of PE by RL (Sobczyk et al. 1993). The other least studied pathway is the control of GL-induction (Cgi) system, which is required to activate the genes by GL (Fig. 3) (Federspiel and Grossman 1990; Li and Kehoe 2005).

Rca mediated chromatic acclimation in F. diplosiphon

Detailed investigation of the Rca pathway revealed the existence of the regulatory element RcaE along with two RRs RcaF and RcaC in F. diplosiphon (Chiang et al. 1992; Cobley et al. 1993; Kehoe and Grossman 1998). Rca is a phytochrome-related two-component regulatory system that was discovered in cyanobacteria (Kehoe and Grossman 1996; Balabas et al. 2003). RcaE is the first module of the Rca system which is a phytochrome-related photosensor protein. It is a 74 kDa soluble protein with histidine kinase activity. RcaE is characterized by the presence of a chromophore-binding GAF domain at its N-terminal, central Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain, and a kinase domain at a C-terminal end (Taylor and Zhulin 1999; Montgomery and Lagarias 2002).

The ΔrcaE strain of F. diplosiphon is characterized by black-color phenotype because genes responsible for PC and PE synthesis, i.e., cpc2, cpeBA and cpeCDE, are expressed at an intermediate level in this strain (Seib and Kehoe 2002; Alvey et al. 2003; Terauchi et al. 2004). The mutants of a histidine residue in ΔrcaE are incapable of activating its downstream RRs due to a lack of phosphorylation. This observation suggested a key role for the histidine residue of RcaE in light-signaling and activation of RR proteins (Kehoe and Grossman 1997; Hirose et al. 2013). Based on different genetic, biochemical and photobiological studies, it is now well-established that RcaE exhibits kinase activity in RL, and a phosphatase activity in GL. In RL, RcaE phosphorylates RR RcaF, which in turn, phosphorylates RR RcaC to modulate its ability to control the transcription of several genes by binding to their promoter sequence (Fig. 3) (Terauchi et al. 2004; Gutu and Kehoe 2012).

The first RR of the Rca pathway, i.e., RcaF, is a single module protein that has conserved contains aspartate and lysine residues. The RcaF coding gene, i.e., rcaF, is found next to the rcaE gene in the genome of F. diplosiphon. The second RR of the Rca pathway is RcaC which is functionally located downstream of RcaF. RcaC is a multi-modular protein that possesses a histidine phosphotransfer module at the N-terminus while DNA binding module is present at C-terminus. Through mutational analysis, it was shown that aspartate residues at 51 and 576 positions undergo phosphorylation in a light-dependent manner during CA (Chiang et al. 1992). Further, Li and Kehoe (2005) and Bezy and Kehoe (2010) demonstrated that phosphorylated RcaC is linked to the activation of the PC biosynthetic gene and the simultaneous repression of genes responsible for PE biosynthesis (Fig. 3).

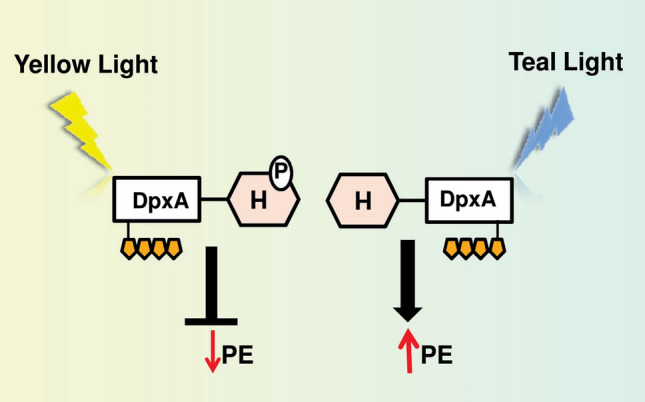

It has been reported that F. diplosiphon possesses another blue-to-yellow light-sensitive photosensor called DpxA to control the accumulation of PE. DpxA works independently of the RcaE system (Wiltbank and Kehoe 2016, 2019). DpxA reacts to teal and yellow lights and adjusts PE levels in the cells (Fig. 4). According to Wiltbank and Kehoe (2016), the autophosphorylation of DpxA by RL leads to partial suppression of genes required for the synthesis of GL-absorbing PE. However, the detailed mechanism of the DpxA-dependent signaling pathway requires further investigation.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of CA by DpxA photosensor in Fremyella diplosiphon. DpxA is responsible for the fine-tuning of the CA response independent of RcaE. DpxA has kinase activity under yellow light and represses PE synthesis; however, the mechanism and effector molecules of this regulation are unclear. In teal light, DpxA is dephosphorylated and there is no inhibition of PE synthesis. DpxA has a light-sensing domain (rectangle) with an attached bilin chromophore (gold pentagon) together with a two-component histidine (H) output domain (hexagon). P represents phosphorylation (color figure online)

Cgi-mediated regulation of chromatic acclimation in F. diplosiphon

The Cgi system possibly regulates GL-activated genes without affecting the RL-dependent PC synthesis (Oelmuller et al. 1988; Federspiel and Grossman 1990; Kahn et al. 1997). However, the Cgi system is less explored than the Rca system. The development of F. diplosiphon null mutants of ΔrcaE and ΔrcaC helped in the analyses of a Cgi pathway that controls the synthesis of PE by GL (Alvey et al. 2003; Li and Kehoe 2005) (Fig. 3). The infCa gene, which encodes translation initiation factor 3α (IF3α), govern PE synthesis during CA in F. diplosiphon via the Cgi pathway (Gutu et al. 2013). However, further work into the signal transduction cascade of the Cgi system is required to test if it involves any photoreceptor similar to the Rca pathway.

Photoregulation of cell and filament length during CA

In wild-type F. diplosiphon, short filaments and spherical cells are observed during growth under RL, whereas long filaments and elongated cells are associated with the growth in GL (Bennett and Bogorad 1973; Bordowitz and Montgomery 2008; Montgomery 2015). The cells of F. diplosiphon ∆rcaE mutant strain are always round and filaments are short, irrespective of the light conditions used during growth (Bennett and Bogorad 1973; Bordowitz and Montgomery 2008). Thus, RcaE is also involved in the regulation of cell shape and filament length, in addition to its well-established function in CA (Bordowitz and Montgomery 2008).

The role of morphogenes has been elucidated for the regulation of cell shape during morphogenesis in cyanobacteria (Hu et al. 2007). MreB is a bacterial morphogene and its functional homologs are found in cyanobacteria (Koksharova et al. 2007; Singh and Montgomery 2014). MreB is required for rod-shaped cells in eubacteria and cyanobacteria and its accumulation in a cell is regulated by the BolA effector molecule (Freire et al. 2009; Singh and Montgomery 2014). In F. diplosiphon, increased expression of the mreB gene results in the induction of rod-shaped morphology under GL. However, increased accumulation of BolA causes a spherical cell shape due to transcriptional downregulation of the MreB encoding gene in RL (Singh and Montgomery 2014). In GL-growth condition, cells accumulate low levels of BolA, which results in the higher expression of mreB and rectangular cells (Singh and Montgomery 2014) (Fig. 3). TonB, which resemble iron-associated proteins, is known to control the cellular morphology of F. diplosiphon under GL (Pattanaik and Montgomery 2010). However, the exact mechanism of TonB-mediated GL-dependent morphogenesis in F. diplosiphon is still unknown.

The altered levels of ROS under GL and RL growth conditions is also responsible for different morphology of cell and filament length under two light conditions (Singh and Montgomery 2012; Walters et al. 2013). The differential accumulation of ROS could be due to the RL-and GL-dependent imbalance in the redox state of PSI and PSII that results in higher ROS accumulation under RL (Campbell et al. 1993; Singh and Montgomery 2012). This observation is also supported by the fact that RL-dependent filament shortening is associated with necrosis in F. diplosiphon (Bennett and Bogorad 1973) and treatment with reducing agent results in long filaments and rod-shaped cells due to decreased levels of ROS under RL (Singh and Montgomery 2012).

Photoregulation of carboxysome biogenesis

RcaE also regulates the structure and the number of carboxysomes in F. diplosiphon (Singh and Montgomery 2014, 2015; Rohnke et al. 2018; Montgomery 2022). Carboxysomes are critical for the CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) in cyanobacteria (Badger and Price 1992; Raven 2003). These microcompartments are required for carbon fixation and their absence results in the requirement of high CO2 for growth (Badger and Price 2003; Rohnke et al. 2018; Kupriyanova et al. 2023). The ΔrcaE mutant of F. diplosiphon grows slower than the wild-type under ambient concentrations of CO2 and RL/GL growth conditions and accumulates high transcript levels of genes required for inorganic carbon (Ci) uptake. These traits indicated the requirement of high carbon linked to bicarbonate uptake (Rohnke et al. 2018).

Also, WT cells possess larger carboxysomes than ΔrcaE mutants (Rohnke et al. 2018). In comparison to growth under RL, smaller carboxysomes are found in WT and ΔrcaE strains under GL growth conditions. However, in comparison to the WT strain, the number of carboxysomes in each cell of the ΔrcaE strain is high under both light conditions (Rohnke et al. 2018). It is important to note that WT and ΔrcaE strains have different cellular morphology, and WT strains possess different cellular and filament morphology under GL and RL. This suggests that cellular shape and division could affect carboxysome spatial organization which is indeed supported by the fact that changes in carboxysome number and position are linked to cytoskeleton-associated alteration in cellular morphology (Gorelova et al. 2013; Rillema et al. 2021).

Engineering photomorphogenesis using synthetic biology tools

Cyanobacteria are one of the best candidates for achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the United Nations. These organisms can be used to ensure a sustainable climate, clean water and energy supply, and agricultural practices (Maurya et al. 2021). However, the successful utilization of cyanobacteria to accomplish SDGs depends on the adjustment of these organisms to the changing light environment. Several light-dependent responses are well-studied in cyanobacteria and other photosynthetic organisms. The outcomes of these studies have resulted in the identification of numerous wavelength-specific sensory and regulatory proteins working in the signaling cascades of light sensing (Dwijayanti et al. 2022; Ohlendorf and Möglich 2022; Leister 2023). These wavelength-specific regulatory networks can be exploited using synthetic biology tools to generate specific responses in cyanobacteria as well as other organisms (Dwijayanti et al. 2022; Opel et al. 2022; Leister 2023). Also, the installation of components of studied photomorphogenesis such as CA can potentially increase the fitness and light-harvesting potential of cyanobacterial strains and/or other distantly related organisms (Dwijayanti et al. 2022; Ohlendorf and Möglich 2022).

However, the installation of a wavelength-specific photoregulatory network could be challenging as it requires the functional alignment of incorporated genes into the genome of the target organism (Dwijayanti et al. 2022). Therefore, improvement of photomorphogenesis in the native strain or its installation in closely or distantly related organisms is currently at a primitive stage. However, as a proof-of-concept, attempts have been made to use available information on the genetics of photomorphogenesis to increase the performance of organisms. Recently, a synthetic genetic network for RL and GL-dependent gene expression was developed using information available on CA found in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. The two light sensing networks were successfully installed in E. coli to regulate the expression of a reporter gene by the quality of light (Ariyanti et al. 2021). Similarly, a far-red light-responsive promoter of Leptolyngbya sp. JSC-1 was successfully installed in Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 9212 to demonstrate the expression of a reporter gene (Liu et al. 2023). Also, a synthetic expression system has been developed that shows very high expression of the reporter gene by GL. This GL-activated expression system includes GL-sensing CcaS photosensor histidine kinase, CcaR response regulator, and promoter of cpcG2 gene derived from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Abe et al. 2014).

Similarly, different truncated versions of CcaS were developed and installed in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Notably, some of these truncated CcaS give increased expression of genes under GL, while one truncated version resulted in higher expression of genes under RL. This RL-dependent induction of genes by truncated version CcaS is just the opposite of its original function of GL-dependent induction of genes (Nakajima et al. 2016). Thus, cyanobacterial optogenetic resource presents an enormous opportunity to engineer cyanobacteria or other photosynthetic organisms using synthetic biology tools to maximize their fitness, light-harvesting capabilities, and production of metabolites under specific light condition. Also, photosensor proteins can be altered randomly by deleting or adding modules in their original forms to create new photosensor proteins exhibiting unique light responses.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The cyanobacterial genome encodes a myriad of photoreceptor and response regulator proteins that help these organisms to interact with light environments. The light signal perceived by photoreceptors is transmitted through response regulators or secondary messenger molecules to drive the developmental processes and metabolic adjustments. Several light-dependent cellular processes are known in cyanobacteria; however, their detailed mechanism of light signal perception and transmission is not well studied. For example, the biosynthetic pathway of photoprotective compounds MAAs and scytonemin is known, however, the mechanism of induction of these compounds by UVR is still unknown. RcaE controls the light-dependent transcription of the bolA gene to control cell morphology, filament length and oxidative stress, independently of RcaF and RcaC. However, the mechanism of RcaE-dependent control of bolA expression is still unknown. Similarly, the mechanism and effector molecules of DpxA-dependent regulation of CA are not known. Also, future research directions require the discovery of new photosensory networks in natural samples and the installation of identified networks in selected cyanobacterial strains using synthetic biology tools.

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), New Delhi (SCP/2022/000201) is greatly acknowledged. This work is also supported by the funding from Institute of Eminence incentive grant, Banaras Hindu University (R/Dev/D/IOE/Incentive/2021-2022/32399). AG thanks ICMR, New Delhi for the senior research fellowship (3/1/3/JRF-2019/HRD-LS). PP is thankful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India (09/0013(15476)/2022-EMR-I) for the junior research fellowships. RG (NTA Ref. No.-211610075296) and ST (NTA Ref. No.-201610202339) are thankful to the UGC, New Delhi, India for the junior research fellowship. We thank Deepa Pandey for reading this manuscript and for making valuable suggestions.

Author contributions

AG, PP and SPS conceptualized the idea. AG, PP and SPS wrote MS. RG developed figures. ST and SPS edited the MS.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abe K, Miyake K, et al. Engineering of a green-light inducible gene expression system in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;7(2):177–183. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostoni M, Montgomery BL. Survival strategies in the aquatic and terrestrial world: the impact of second messengers on cyanobacterial processes. Life. 2014;4:745–769. doi: 10.3390/life4040745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostoni M, Koestler BJ et al (2013) Occurrence of cyclic di-GMP-modulating output domains in cyanobacteria: an illuminating perspective. mBio 4:e00451–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alvey RM, Karty JA, et al. Lesions in phycoerythrin chromophore biosynthesis in Fremyella diplosiphon reveal coordinated light regulation of apoprotein and pigment biosynthetic enzyme gene expression. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2448–2463. doi: 10.1105/tpc.015016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders K, Daminelli-Widany G, et al. Structure of the cyanobacterial phytochrome 2 photosensor implies a tryptophan switch for phytochrome signaling. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35714–35725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyanti D, Ikebukuro K, Sode K. Artificial complementary chromatic acclimation gene expression system in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20:128. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babin M, Stramski D, et al. Variations in the light absorption coefficients of phytoplankton, non-algal particles, and dissolved organic matter in coastal waters around Europe. J Geophys Res Oceans. 2003 doi: 10.1029/2001JC000882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. The CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria and microalgae. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:606–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb04711.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:609–622. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabas BE, Montgomery BL, et al. CotB is essential for complete activation of green light-induced genes during complementary chromatic adaptation in Fremyella diplosiphon. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:781–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardall J, Stojkovic S, Larsen S. Living in a high CO2 world: impacts of global climate change on marine phytoplankton. Plant Ecol Divers. 2009;2:191–205. doi: 10.1080/17550870903271363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bebout BM, Garcia-Pichel F. UV B-induced vertical migrations of cyanobacteria in a microbial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61(12):4215–4222. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4215-4222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrenfeld MJ, O'Malley RT, et al. Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity. Nature. 2006;444:752–755. doi: 10.1038/nature05317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A, Bogorad L. Complementary chromatic adaptation in a filamentous blue-green alga. J Cell Biol. 1973;58(2):419–435. doi: 10.1083/jcb.58.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezy RP, Kehoe DM. Functional characterization of a cyanobacterial OmpR/PhoB class transcription factor binding site controlling light color responses. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5923–5933. doi: 10.1128/JB.00602-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D (2016) In the limelight: photoreceptors in cyanobacteria. mBio 7(3):e00741–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bhaya D, Takahashi A, Grossman AR. Light regulation of type IV pilus-dependent motility by chemosensor-like elements in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7540–7545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131201098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt-Oliveira MDC, Buch B, et al. Effects of light intensity and temperature on Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (cyanobacteria) with straight and coiled trichomes: growth rate and morphology. Braz J Biol. 2012;72:343–351. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842012000200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordowitz JR, Montgomery BL. Photoregulation of cellular morphology during complementary chromatic adaptation requires sensor-kinase-class protein RcaE in Fremyella diplosiphon. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(11):4069–4074. doi: 10.1128/JB.00018-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudler R, Hitomi K, et al. Identification of a new cryptochrome class: structure, function, and evolution. Mol Cell. 2003;11(1):9–67. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchberger T, Lamparter T. Streptophyte phytochromes exhibit an N-terminus of cyanobacterial origin and a C-terminus of proteobacterial origin. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgie ES, Bussell AN, et al. Crystal structure of the photosensing module from a red/far-red light-absorbing plant phytochrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:10179–10184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403096111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AW, Montgomery BL. The tryptophan-rich sensory protein (TSPO) is involved in stress-related and light-dependent processes in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1393. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler WL, Norris KH, et al. Detection, assay, and preliminary purification of the pigment controlling photoresponsive development of plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1959;45:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.45.12.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzadilla PI, Kirilovsky D. Revisiting cyanobacterial state transitions. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2020;19(5):585–603. doi: 10.1039/c9pp00451c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D. Complementary chromatic adaptation alters photosynthetic strategies in the cyanobacterium Calothrix. Microbiology. 1996;142:1255–1263. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Houmard J, de Marsac NT. Electron transport regulates cellular differentiation in the filamentous cyanobacterium Calothrix. Plant Cell. 1993;5(4):451–463. doi: 10.2307/3869725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Eriksson M-J, et al. The cyanobacterium Synechococcus resists UV-B by exchanging photosystem II reaction-center D1 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:364–369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell EL, Hagen KD, et al. Genetic analysis reveals the identity of the photoreceptor for phototaxis in hormogonium filaments of Nostoc punctiforme. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:782–791. doi: 10.1128/JB.02374-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey ES, Grossman AR. In vivo and in vitro characterization of the light-regulated cpcB2A2 promoter of Fremyella diplosiphon. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6362–6374. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6362-6374.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore AR, Jarillo JA, et al. Cryptochromes: blue light receptors for plants and animals. Science. 1999;284(5415):760–765. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castenholz RW, Garcia-Pichel F. Cyanobacterial responses to UV-radiation. In: Whitton BA, editor. The ecology of cyanobacteria II: their diversity in space and time. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2012. pp. 481–499. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan AG, Swan JA, et al. Reconstitution of an intact clock reveals mechanisms of circadian timekeeping. Science. 2021;374(6564):eabd4453. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazan A, Das I, et al. Phototrophy by antenna-containing rhodopsin pumps in aquatic environments. Nature. 2023;615:535–540. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Chory J, Fankhauser C. Light signal transduction in higher plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:87–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang GG, Schaefer MR, Grossman AR. Complementation of a red-light-indifferent cyanobacterial mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(20):9415–9419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukhutsina VU, van Thor JJ. Molecular activation mechanism and structural dynamics of orange carotenoid protein. Physchem. 2022;2(3):235–252. doi: 10.3390/physchem2030017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuon K, Shim JG, et al. Natural selection of carotenoid binding in Gloeobacter rhodopsin. Algal Res. 2023;74:103232. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2023.103232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cobley JG, Miranda RD. Mutations affecting chromatic adaptation in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. J Bacteriol. 1983;153(3):1486–1492. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1486-1492.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobley JG, Zerweck E, et al. Construction of shuttle plasmids which can be efficiently mobilized from Escherichia coli into the chromatically adapting cyanobacterium, Fremyella diplosiphon. Plasmid. 1993;30:90–105. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobley JG, Clark AC, et al. CpeR is an activator required for expression of the phycoerythrin operon (cpeBA) in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon and is encoded in the phycoerythrin linker-polypeptide operon (cpeCDESTR) Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(6):1517–1531. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley PB, Lemaux PG, Grossman AR. Cyanobacterial light-harvesting complex subunits encoded in two red light induced transcripts. Science. 1985;230:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.3931221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley PB, Lemaux PG, et al. Genes encoding major light harvesting polypeptides are clustered on the genome of the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3924–3928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley PB, Lemaux PG, Grossman AR. Molecular characterization and evolution of sequences encoding light-harvesting components in the chromatically adapting cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. J Mol Biol. 1988;199:447–465. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90617-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. The LOV domain family: photoresponsive signaling modules coupled to diverse output domains. Biochemistry. 2003;42(1):2–10. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Marsac NT. Phycobilisomes and complementary chromatic adaptation in cyanobacteria. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1983;81(3):201–254. [Google Scholar]

- de Marsac NT, Cohen-Bazire G. Molecular composition of cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:1635–1639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.4.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Martín MA, Sauer PV, et al. Structures of a phycobilisome in light-harvesting and photoprotected states. Nature. 2022;609(7928):835–845. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwijayanti A, Zhang, , et al. Toward multiplexed optogenetic circuits. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;9:804563. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.804563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann TW. Farbe und assimilation. Assimilation findet nur in den farbstoffhaltigen plasmathielchen statt II Näherer zusamennhang zwischen lichtabsorption und assimilation. Bot Z. 1883;41:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann TW. Untersuchungen über die qualitativen beziehungen zwieschen absorbtion des lichtes und assimilation in pflanzenzellen. I. Das mikrospectraphotometer, ein apparat zur qualitativen mikrospectralanalyse. II. Experimentelle grundlangen zur ermittelung der quantitativen beziehungen zwieschen assimilationsenergie und absorptiongrösse. III. Bestimmung der vertheilung der energie im spectrum von sonnenlicht mittels bacterienmethode und quantitativen mikrospectralanalyse. Bot Z. 1902;42:81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto G, Nomura R, et al. Cyanobacteriochrome SesA is a diguanylate cyclase that induces cell aggregation in Thermosynechococcus. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:24801–24809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.583674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto G, Ni-Ni-Win, et al. Three cyanobacteriochromes work together to form a light color-sensitive input system for c-di-GMP signaling of cell aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:8082–8087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504228112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto G, Wallner T, Wilde A. Control of light-dependent behaviour in cyanobacteria by the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Microlife. 2023;4:uqad019. doi: 10.1093/femsml/uqad019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everroad C, Six C, et al. Biochemical bases of type IV chromatic adaptation in marine Synechococcus sp. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(9):3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3345-3356.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M, Chavan AG, et al. Synchronization of the circadian clock to the environment tracked in real time. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120(13):e2221453120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2221453120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federspiel NA, Grossman AR. Characterization of the light-regulated operon encoding the phycoerythrin-associated linker proteins from the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4072–4081. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.4072-4081.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federspiel NA, Scott L. Characterization of a light-regulated gene encoding a new phycoerythrin-associated linker protein from the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5994–5998. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5994-5998.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler B, Broc D, et al. Involvement of cyanobacterial phytochromes in growth under different light qualities and quantities. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79:551–555. doi: 10.1562/RN-013R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P, Moreira RN, Arraiano CM. BolA inhibits cell elongation and regulates MreB expression levels. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushimi K, Narikawa R. Cyanobacteriochromes: photoreceptors covering the entire UV-to-visible spectrum. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2019;57:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY. Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: diversity of output domains and domain combinations. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4169–4182. doi: 10.1128/JB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan F, Bryant DA. Adaptive and acclimative responses of cyanobacteria to far-red light. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17(10):3450–3465. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan F, Zhang S, et al. Extensive remodeling of a cyanobacterial photosynthetic apparatus in far-red light. Science. 2014;345:1312–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1256963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendel S, Ohad I, Bogorad L. Control of phycoerythrin synthesis during chromatic adaptation. Plant Physiol. 1979;64(5):786–790. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisriel CJ, Elias E, et al. Helical allophycocyanin nanotubes absorb far-red light in a thermophilic cyanobacterium. Sci Adv. 2023;9(12):eadg0251. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adg0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JB, Kretz CB, et al. Current perspectives on microbial strategies for survival under extreme nutrient starvation: evolution and ecophysiology. In: Bakermans C, et al., editors. Microbial evolution under extreme conditions. Berlin: De Gruyter; 2015. pp. 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelova OA, Baulina OI, et al. The pleiotropic effects of ftn2 and ftn6 mutations in cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942: an ultrastructural study. Protoplasma. 2013;250:931–942. doi: 10.1007/s00709-012-0479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutu A, Kehoe DM. Emerging perspectives on the mechanisms, regulation, and distribution of light color acclimation in cyanobacteria. Mol Plant. 2012;5(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutu A, Nesbit AD, et al. Unique role for translation initiation factor 3 in the light color regulation of photosynthetic gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(40):16253–16258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306332110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YY, Häder D-P. Reactive oxygen species and UV-B: effect on cyanobacteria. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:729–736. doi: 10.1039/b110365m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(4):263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose Y, Shimada T, et al. Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS is the green light receptor that induces the expression of phycobilisome linker protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9528–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801826105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose Y, Narikawa R, et al. Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS regulates phycoerythrin accumulation in Nostoc punctiforme, a group II chromatic adapter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8854–8859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000177107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose Y, Rockwell NC, et al. Green/red cyanobacteriochromes regulate complementary chromatic acclimation via a protochromic photocycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4974–4979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard J, Capuano V, et al. Genes encoding core components of the phycobilisome in the cyanobacterium Calothrix sp. strain PCC 7601: occurrence of a multigene family. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5512–5521. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5512-5521.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard J, Capuano V, et al. Molecular characterization of the terminal energy acceptor of cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2152–2156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Yang G, et al. MreB is important for cell shape but not for chromosome segregation of the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1640–1652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DY, Park S, et al. GIGANTEA regulates the timing stabilization of CONSTANS by altering the interaction between FKF1 and ZEITLUPE. Mol Cells. 2019;42(10):693. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2019.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi M, Ishizuka T. Cyanobacteriochromes: a new superfamily of tetrapyrrole-binding photoreceptors in cyanobacteria. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2008;7:1159–1167. doi: 10.1039/b802660m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imasheva ES, Balashov SP, et al. Reconstitution of Gloeobacter violaceus rhodopsin with a light-harvesting carotenoid antenna. Biochemistry. 2009;48(46):10948–10955. doi: 10.1021/bi901552x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka T, Shimada T, et al. Characterization of cyanobacteriochrome TePixJ from a thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus strain BP-1. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47(9):1251–1261. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GI. Signal transduction in responses to UV-B radiation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:407–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y, Lin R. Transcriptional regulatory network of the light signaling pathways. New Phytol. 2020;227(3):683–697. doi: 10.1111/nph.16602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Trivedi VD, Spudich JL. Demonstration of a sensory rhodopsin in eubacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1513–1522. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Mazel D, et al. A role for cpeYZ in cyanobacterial phycoerythrin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:998–1006. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.998-1006.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe DM, Grossman AR. Similarity of a chromatic adaptation sensor to phytochrome and ethylene receptors. Science. 1996;273:1409–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe DM, Grossman AR. New classes of mutants in complementary chromatic adaptation provide evidence for a novel four-step phosphorelay system. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3914–3921. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3914-3921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe DM, Grossman AR. Use of molecular genetics to investigate complementary chromatic adaptation: advances in transformation and complementation. Methods Enzymol. 1998;297:279–290. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(98)97021-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe DM, Gutu A. Responding to color: the regulation of complementary chromatic adaptation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayatan B, Meeks JC, Risser DD. Evidence that a modified type IV pilus-like system powers gliding motility and polysaccharide secretion in filamentous cyanobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2015;98(6):1021–1036. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koksharova OA, Klint J, Rasmussen U. Comparative proteomics of cell division mutants and wild-type of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. Microbiology. 2007;153(8):2505–2517. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronfel CM, Hernandez CV, et al. CpeF is the bilin lyase that ligates the doubly linked phycoerythrobilin on β-phycoerythrin in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(11):3987–3999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.007221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K, Mella-Herrera RA, et al. Cyanobacterial heterocysts. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(4):a000315. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Maurya PK, et al. Photomorphogenesis in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon improves photosynthetic efficiency. In: Mishra AK, Tiwari DN, Rai AN, et al., editors. Cyanobacteria. San Diego: Academic Press, Elsevier Inc.; 2019. pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kupriyanova EV, Pronina NA, Los DA. Adapting from low to high: an update to CO2-concentrating mechanisms of cyanobacteria and microalgae. Plants. 2023;12(7):1569. doi: 10.3390/plants12071569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb JJ, Røkke G, Hohmann-Marriott MF. Chlorophyll fluorescence emission spectroscopy of oxygenic organisms at 77 K. Photosynthetica. 2018;56(1):105–124. doi: 10.1007/s11099-018-0791-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leister D. Enhancing the light reactions of photosynthesis: strategies, controversies, and perspectives. Mol Plant. 2023;16(1):4–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Kehoe DM. In vivo analysis of the roles of conserved aspartate and histidine residues within a complex response regulator. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1538–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TS, Wu KF, et al. Identification of a far-red light-inducible promoter that exhibits light intensity dependency and reversibility in a cyanobacterium. ACS Synth Biol. 2023;12(4):1320–1330. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.3c00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losi A, Polverini E, et al. First evidence for phototropin-related blue-light receptors in prokaryotes. Biophys J. 2002;82(5):2627–2634. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75604-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani O, Haffner M, et al. Roles of second messengers in the regulation of cyanobacterial physiology: the carbon-concentrating mechanism and beyond. Microlife. 2023;4:uqad008. doi: 10.1093/femsml/uqad008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher T, Helmann JD, Unden G. Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70(4):910–938. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascoli V, Bhatti AF, et al. The antenna of far-red absorbing cyanobacteria increases both absorption and quantum efficiency of Photosystem II. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3562. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31099-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S. Light detection and signal transduction in the BLUF photoreceptors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54(2):171–179. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Hasegawa K, et al. Light-induced structural changes in a putative blue-light receptor with a novel FAD binding fold sensor of blue-light using FAD (BLUF); Slr1694 of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochemistry. 2004;43(18):5304–5313. doi: 10.1021/bi049836v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya PK, Mondal S, et al. Roadmap to sustainable carbon-neutral energy and environment: can we cross the barrier of biomass productivity? Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:49327–49342. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15540-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya PK, Kumar V, et al. Chromatic acclimation in cyanobacteria: photomorphogenesis in response to light quality. In: Rastogi RP, et al., editors. Ecophysiology and biochemistry of cyanobacteria. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2022. pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya PK, Mondal S, et al. Green and blue light-dependent morphogenesis, decoupling of phycobilisomes and higher accumulation of reactive oxygen species and lipid contents in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Environ Exp Bot. 2023;205:105105. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2022.105105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel D, Guglielmi G, et al. Green light induces transcription of the phycoerythrin operon in the cyanobacterium Calothrix 7601. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:8279–8290. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.21.8279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell MD, Koop R, et al. Regulation of the distribution of chlorophyll and phycobilin-absorbed excitation energy in cyanobacteria. A structure-based model for the light state transition. Plant Physiol. 2002;130(3):1201–1212. doi: 10.1104/pp.009845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BL. Sensing the light: photoreceptive systems and signal transduction in cyanobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64(1):16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BL. Light-dependent governance of cell shape dimensions in cyanobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:514. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BL. Mechanisms and fitness implications of photomorphogenesis during chromatic acclimation in cyanobacteria. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(14):4079–4090. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BL. Reflections on cyanobacterial chromatic acclimation: exploring the molecular bases of organismal acclimation and motivation for rethinking the promotion of equity in STEM. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2022;86(3):e00106–e121. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00106-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BL, Lagarias JC. Phytochrome ancestry: sensors of bilins and light. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(8):357–366. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon YJ, Park YM, et al. Calcium is involved in photomovement of cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79:114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2004.tb09865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon YJ, Kim SY, et al. Cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph2 is a negative regulator in phototaxis toward UV-A. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:335–334. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzopappa F, Kirilovsky D. Changing color for photoprotection: the orange carotenoid protein. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25(1):92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]