Abstract

Objective:

Feedback on neuropsychological assessment is a critical part of clinical practice, but there are few empirical papers on neuropsychological feedback practices. We sought to fill this gap in the literature by surveying practicing neuropsychologists in the United States. Questions addressed how they provide verbal and written feedback to patients and referral sources. Survey questions also addressed billing practices and training in the provision of feedback.

Methods:

A survey was developed using Qualtrics XM to survey currently licensed, independently practicing clinical neuropsychologists in the United States about their feedback practices. The survey was completed by 184 individuals.

Results:

Nearly all respondents reported that they provide verbal feedback to patients, most often in-person, within three weeks following testing. Typically, verbal feedback sessions with patients last 45 minutes. Verbal feedback was provided to referrals by about half of our sample, typically via a brief phone call. Most participants also reported providing written feedback to both the patient and referring provider, most commonly via the written report within three weeks after testing. Regarding billing, most respondents use neuropsychological testing evaluation codes. The COVID-19 pandemic appeared to have had a limited impact on the perceived effectiveness and quality of verbal feedback sessions. Finally, respondents reported that across major stages of professional development, training in the provision of feedback gradually increased but was considered inadequate by many participants.

Conclusions:

Results provide an empirical summary of the “state of current practice” for providing neuropsychological assessment feedback. Further experimental research is needed to develop an evidence-base for effective feedback practices.

Keywords: feedback, neuropsychological assessment, survey, practices, training

Feedback following a psychological evaluation involves provision of written and/or verbal information to a patient, family member, legal guardian, or others involved in the patient’s care, such as referring providers. The provision of feedback is critically important, being an ethical standard in psychology that is specifically addressed in ethics code 9.10, which states that reasonable steps must be taken to ensure that evaluation results are communicated to patients or a designated other (APA, 2017). Similarly, a key component of a clinical neuropsychological evaluation is the provision of neuropsychological assessment feedback (NAF). Guidelines for providing feedback are delineated in the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) Practice Guidelines for Neuropsychological Assessment and Consultation (AACN Board of Directors, 2007). NAF is a specific type of feedback that emphasizes explaining implications of cognitive test performances and facilitating comprehension of the patient’s neurocognitive symptoms or syndromes (Postal & Armstrong, 2013). Further goals of feedback include providing patients and their families with a better understanding of the functional implications of a diagnosis, its impact on occupational duties, academics, and interpersonal matters, and recommendations to address areas of concern. NAF can also have a therapeutic emphasis when delivered to patients by intentionally aiming to reduce distress and anxiety, and it is viewed by some providers as a form of intervention (Postal & Armstrong, 2013).

While the literature on the influence of feedback on patient outcomes is limited, some of the extant research from health psychology and healthcare informatics literatures suggests that providing a transparent explanation of patient health status can provide a sense of cognitive control and improve health outcomes (Meyer & Mark, 1995; Tapuria et al., 2021). Pegg et al. (2005) investigated the effects of providing detailed information on injury characteristics and treatment to patients with traumatic brain injury and found that those who received this information made greater functional improvements, were more invested in treatment, and were more satisfied with their rehabilitation. Similarly, a recent large scoping review conducted by Gruters et al. (2022) included several studies that indicated that provision of NAF led to high patient satisfaction with the neuropsychological assessment. Furthermore, there was evidence that feedback was related to increased quality of life, a better understanding of cognitive strengths and weaknesses, and increased understanding of how to effectively address symptoms among patients. These authors suggest that NAF should be standard clinical practice in the provision of neuropsychological assessment.

It is important to note that the majority of studies reviewed by Gruters et al. (2022) surveyed patients and not clinical neuropsychologists. The exception was a study by Martin and Schroeder (2021), who examined feedback practices among neuropsychologists regarding invalid test results and found little consensus regarding approaches to providing feedback in the context of invalid test results.

To our knowledge, there has been only a single published study that specifically surveyed clinical neuropsychologists’ feedback practices. Smith et al. (2007) surveyed 719 psychologist members of the International Neuropsychological Society (INS), National Academy of Neuropsychology (NAN), and Society for Personality Assessment (SPA) to examine their feedback practices and perceptions of the effects of feedback on patients and families. These researchers found that 71.3% of respondents frequently provide in-person feedback to patients while 63.6% provide written reports. Feedback sessions were typically 50 to 60 minutes in duration, and sessions longer than 30 minutes were perceived to contribute to higher levels of patient satisfaction compared to shorter sessions. Feedback sessions were also perceived to facilitate open dialogue, increase patients’ understanding of presenting condition, and improve the overall patient experience (Smith et al., 2007).

Other studies have investigated feedback practices of clinical psychologists in general (i.e., not specific to the field of neuropsychology). In a survey of 468 participants, Curry and Hanson (2010) found that 91.7% of the sample provided verbal feedback to patients at least “sometimes” while 35% provided verbal feedback to all patients. The main reason for not providing feedback was concern for potential harm to the patient, though legal limitations in forensic cases and employment screening contexts were also noted. Additionally, 70.8% reported providing a written summary to patients at least “sometimes”, while most respondents (68.4%) indicated that they rarely or never provided patients with a copy of the actual test results (Curry & Hanson, 2010). In an effort to replicate Curry and Hanson (2010), Jacobson et al. (2015) conducted a survey of 399 Canadian psychologists and found that most (91%) provided verbal feedback frequently or almost always. Verbal feedback was the most common modality (88.2%), followed by written feedback (60.2%). Most participants reported ensuring that patients understood results (91.9%), highlighting implications of results (95.2%), and allowing opportunities to ask questions (94.7%) in feedback sessions (Jacobson et al., 2015).

Jacobson et al. (2015) also inquired about participants’ experiences with training in feedback. They found that about a third of participants reported that graduate and postgraduate training were neutral or unhelpful in preparing them to deliver feedback. Participants reported that actual clinical experience and discussions with supervisors were the most common forms of training in the provision of feedback, and most learned to provide feedback through trial-and-error and self-instruction (Jacobson et al, 2015). Similarly, Curry and Hanson (2010) found that about a third of participants felt they received little to no training in providing feedback across graduate, internship, and postdoctoral training.

In summary, prior research suggests that providing feedback is common practice in clinical psychology, but empirical data is lacking on feedback practices specific to clinical neuropsychology. Thus, there is a need for contemporary neuropsychological research in this area, with a specific goal of characterizing important aspects of clinical neuropsychologists’ feedback practices to inform modern clinical practice. This goal was considered particularly important in the wake of substantial changes to neuropsychological assessment practice during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hewitt & Loring, 2020). Therefore, we surveyed clinical neuropsychologists across the United States to address the following aims.

- Evaluate neuropsychologists’ practices regarding verbal feedback provided to patients, including:

- The frequency, modality, and timing of feedback;

- The content and style of verbal feedback, including approaches to providing feedback, content of feedback sessions, perceived barriers to successful feedback, and perceived strategies that lead to successful feedback;

- Billing and reimbursement practices regarding feedback; and

- Changes to feedback practices associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, including impact of the pandemic on the mode, perceived effectiveness, and frequency of feedback.

Assess neuropsychologists’ practices regarding written feedback provided to patients, including the frequency, modality, and timing of feedback.

Examine neuropsychologists’ practices regarding verbal and written feedback provided to referring providers, including the frequency, modality, and timing of feedback.

Evaluate neuropsychologists’ perspectives on their training in the provision of neuropsychological assessment feedback.

Method

Survey

We distributed an online survey using Qualtrics XM (please refer to supplemental material for a copy of the survey). Initial screening questions included a captcha question to reduce the frequency of spam responses, followed by four questions inquiring about key inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) being a currently licensed psychologist who is practicing independently, 2) identifying as a clinical neuropsychologist, 3) primarily working in a clinical practice setting (e.g., as opposed to forensic or research), and 4) currently practicing in the United States. The survey was restricted to neuropsychologists within the United States due to survey questions inquiring about billing and reimbursement, which differ significantly between countries. The survey included items inquiring about participants’ demographics and their professional characteristics (i.e., degree area and type, board certification status, years of practice, etc.) and work setting. The main body of the survey consisted of five sections with 59 questions that covered verbal and written feedback practices with patients, verbal and written feedback practices with providers, and perspectives on respondents’ previous training in the delivery of feedback. Survey questions took several different forms depending on the objectives of each unique question, including multiple choice (some questions allowed for multiple responses while others allowed only a single response), rank-order, Likert scale, and open-ended. Constant sum options were also used.

Procedure

The study was determined to have exempt status by a local institutional Internal Review Board (IRB) prior to data collection. The survey was disseminated on the following professional listervs: Society for Clinical Neuropsychology Early Career Neuropsychology Committee listserv (696 subscribers), American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology member (number of subscribers unknown) and community discussion (2,113 subscribers) listservs, and the NPsych listserv (4,246 subscribers). The survey was initially distributed on 10/06/2022 and closed six weeks later on 11/16/22. The email sent to these listservs provided an overview of the survey, estimated completion time, disclosure of compensation, and link to the survey. Reminder emails were sent to all four listservs on 10/19/2022 and 11/02/2022. Two of the authors (AK and CB) also posted on Twitter, describing the study and asking individuals to email the first author to obtain the survey link. We received over 100 email inquiries from the Twitter posts, only four of which were legitimate inquiries (i.e., not spam). Several strategies were used to screen email inquiries. If emails originated from an institutional domain, the link was provided. If emails were from general domains with no signature, but did not appear suspicious, we responded requesting that they respond back using their institutional email. Messages that were obviously odd or nonsensible were not provided the link. Participants received a $5 Amazon e-gift card as compensation.

Participants

The survey was accessed (i.e., opened but not necessarily completed) 243 times, and 59 of those responses were excluded for various reasons (described below). Eight respondents did not give informed consent and therefore were not permitted to access any survey questions. Reasons for exclusion involved responses not meeting initial inclusion criteria as defined by the first four questions of the survey, including not being a licensed psychologist who is practicing independently (n = 7), not practicing in the United States (n = 6), or the primary area of practice being forensic (n = 5) or academic research (n = 1). Other participants were excluded for skipping 75% or more of the survey questions (n = 35). Demographics for these 35 individuals were consistent with the 184 participants included for analysis (see supplemental material). The median amount of time to complete the survey was 19.8 minutes, and the average response rate to survey questions was 92.8% (SD = 6.65%). All responses from all 184 respondents were retained for analysis. The demographic characteristics and geographic settings of the participants are presented in Table 1. Information pertaining to respondents’ professional demographics are presented in Table 2. Please refer to supplemental material for reported memberships to professional organizations.

Table 1.

Basic Demographics of Total Sample (N = 184)

| Variable | M or n | SD or % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (n = 181) | 43.8 (30–76) | 9.95 |

| Gender (n = 184) | ||

| Male | 45 | 24.5% |

| Female | 135 | 73.4% |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 | 1.1% |

| Non-binary | 1 | 0.5% |

| Other | 1 | 0.5% |

| Transgender | 0 | 0.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity (n = 184) | ||

| Caucasian/ White | 161 | 87.5% |

| Asian/ Asian American or Pacific Islander | 6 | 3.3% |

| Biracial/ Multiracial/ Multiethnic | 5 | 2.7% |

| I prefer not to answer | 5 | 2.7% |

| African American/ Black | 4 | 2.2% |

| Hispanic/ Latino(a/o), Latinx | 3 | 1.6% |

| American Indian/ Alaskan Native | 0 | 0.0% |

| Geographic Setting (n = 184) | ||

| Urban | 116 | 63.0% |

| Suburban | 43 | 23.4% |

| Multiple | 14 | 7.6% |

| Rural | 11 | 6.0% |

Note: M = mean; n = number of respondents; SD = standard deviation

Table 2.

Professional Demographics of Total Sample (N = 184)

| Variable | M or n | SD or % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Degree Type (n =183) | ||

| Ph.D. | 138 | 75.0% |

| Psy.D. | 45 | 24.5% |

| Degree Area (N = 184) | ||

| Clinical Psychology | 163 | 88.6% |

| Counseling Psychology | 13 | 7.1% |

| School Psychology | 2 | 1.1% |

| Clinical Forensic Psychology | 1 | 0.5% |

| Clinical Health Psychology | 1 | 0.5% |

| Experimental Cognition | 1 | 0.5% |

| Experimental Psychology | 1 | 0.5% |

| Neuropsychology | 1 | 0.5% |

| Rehabilitation Psychology | 1 | 0.5% |

| Professional Identity (N = 184) | ||

| Adult Neuropsychologist | 117 | 63.6% |

| Pediatric Neuropsychologist | 26 | 14.1% |

| Lifespan Neuropsychologist | 25 | 13.6% |

| Geriatric Neuropsychologist | 12 | 6.5% |

| Adult and Geriatric Neuropsychologist | 2 | 1.1% |

| Rehabilitation Neuropsychologist | 2 | 1.1% |

| Board Certification (N = 184) | ||

| ABPP-CN | 93 | 50.5% |

| Not Board-Certified | 89 | 48.4% |

| ABRP | 4 | 2.2% |

| ABN | 3 | 1.6% |

| ABPP-CN (Pediatric) | 3 | 1.6% |

| ABPP-FP | 1 | 0.5% |

| Years Practicing Independently (N = 184) | 11.16 | 9.56 |

| Work Setting (N = 184) | ||

| Academic Medical Center | 57 | 31.0% |

| Independent Private Practice | 29 | 15.8% |

| Veterans Affairs Hospital | 28 | 15.2% |

| Group Practice | 20 | 10.9% |

| Private/ Community Hospital | 17 | 9.2% |

| Rehabilitation Hospital | 13 | 7.1% |

| Children’s Hospital | 8 | 4.3% |

| Outpatient Freestanding Clinic | 7 | 3.8% |

| Equal Time at Medical Center and Private Practice | 2 | 1.1% |

| District Hospital | 1 | 0.5% |

| Military Health Center | 1 | 0.5% |

| Multi-State Hospital System | 1 | 0.5% |

| Department Type (N = 184) | ||

| Neuropsychology | 67 | 36.4% |

| Behavioral Health/ Mental Health | 43 | 23.4% |

| Neurology | 37 | 20.1% |

| Psychology | 32 | 17.4% |

| Not Applicable | 21 | 11.4% |

| Psychiatry | 21 | 11.4% |

| Physical Medicine/ Rehabilitation | 20 | 10.9% |

| Neuroscience | 13 | 7.1% |

| Pediatrics | 6 | 3.3% |

| Geriatrics | 4 | 2.2% |

| Neurosurgery | 3 | 1.6% |

| Primary Care/ Family Medicine/ Internal Medicine | 3 | 1.6% |

| Hematology/ Oncology | 1 | 0.5% |

| Surgery | 1 | 0.5% |

| Types of Evaluations (N = 184) | ||

| Outpatient | 157 | 85.3% |

| Both Inpatient and Outpatient | 21 | 11.4% |

| Inpatient | 6 | 3.3% |

| Supervision of Trainees (N = 184) | ||

| Yes | 102 | 55.4% |

| No | 82 | 44.6% |

Note: M = mean; n = number of respondents; SD = standard deviation; ABPP = American Board of Professional Psychology; ABRP = American Board of Professional Psychology-Rehabilitation Psychology; ABN = American Board of Neuropsychology; CN = Clinical Neuropsychology; FP = Forensic Psychology; Psy.D. = Doctor of Psychology; Ph.D. = Doctor of Philosophy

Results

Verbal Feedback to Patients

Frequency of Verbal Feedback to Patients

Nearly all (98.4%, n = 181) of our sample reported that they provide verbal feedback to patients after the evaluation is completed and do so for an average of 92.3% of patients. Of the 94 respondents who reported that they do not provide feedback for at least some of their patients, 71.3% reported their reason to be that patients sometimes decline their offer of a feedback session (see Figure 1). Additionally, verbal feedback is not provided to some patients because results will be reviewed by an interdisciplinary team (30.9%), or feedback will only be provided to the referral source (26.6%). Additional reasons (i.e., “other” responses) for not providing feedback included patient no shows, difficulties contacting patients, and limitations associated with independent medical evaluations or forensic evaluations.

Figure 1. Reasons for not Providing Verbal Feedback to Some Patients (n = 94).

Note. 1= Patients sometimes decline; 2= Other; 3=Results are reviewed by an interdisciplinary team; 4= I sometimes only provide feedback to the referral source; 5= I sometimes only provide written feedback to patients; 6= Time constraints; 7= Reimbursement rate. Multiple responses were allowed; therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Modality for Delivering Feedback

Respondents indicated that they provide in-person feedback to patients 56% of the time on average, while videoconferencing technology (i.e., a televideo platform) or the telephone is used 33.3% and 10.8% of the time, respectively (see Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

a. Percent of the Time Various Modalities are Used for Feedback to Patients (n = 181)

b. Earliest Stage in Evaluation in which Any Feedback is Provided to Patient on Test Performance (n = 181)

c. Length of Time After Testing Until Feedback Session (n = 181)

Timing of Feedback

Respondents reported spending 45.2 minutes on average providing verbal feedback sessions per patient (SD = 17.5). We also asked respondents about the earliest stage in the assessment process that any feedback is provided about test performance, and 45.9% of the sample reported that some preliminary feedback is provided to patients after testing and scoring is completed but prior to completing the report. Another 26.5% reported that feedback is only provided after everything, including the report, is complete (see Figure 2b). Feedback sessions are typically provided about 1–2 weeks (35.9%) or 2–3 weeks (26%) after completion of testing, although some also deliver feedback within one week (18.8%) or on the same day (14.9%; see Figure 2c). Respondents also reported that they verbally communicate with their patients after feedback sessions to answer questions about assessment results or recommendations 26% of the time (n = 180; SD = 33.6%), and follow-up sessions are provided after the initial feedback session 9% of the time (n = 180; SD = 19.2%).

Content and Style of Verbal Feedback to Patients

Approaches to Providing Verbal Feedback and Components of Feedback Session.

As shown in Figure 3, 23.2% of the sample show and discuss raw test scores with patients and 17.1% show and discuss actual test protocols. About half of the sample have the report in-hand or on the computer and walk their patients through the report during the feedback session, while 22.1% reported using the same approach with the written summary. A small portion of the sample use a slideshow-type presentation (3.9%), while about half the sample reported utilizing some other visual aid, the most common being a normal/bell curve and bar graphs/charts of test data.

Figure 3. Most Common Approaches to Providing Verbal Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n = 181).

Note. 1= Report in-hand/on computer, and walk patient through results, impressions, and recommendations; 2= Utilize a visual aid that is not a slideshow; 3= Show and discuss raw data/scores (such as a data table); 4= Separate written summary in-hand/on computer, and walk patient through results, impressions, and recommendations; 5= Do not use any written or visual aids during verbal feedback sessions; 6= Show and discuss test protocols; 7= Utilize a slideshow-type presentation. Multiple responses were allowed; therefore, percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Respondents were also asked to identify up to five of the most important components that they typically include in a feedback session (see Figure 4). Nearly all respondents (91.2%) indicated that discussing recommendations was an important component of NAF. Answering questions about assessment results was endorsed to a similar extent (82.3%). The next most frequent responses included discussing diagnoses and differential diagnoses (63%), explaining test results (55.8%), discussing the implications of results as they pertain to daily functioning (48.6%) and as they pertain to presenting concerns/referral questions (43.6%), as well as ensuring understanding of results and diagnoses (44.8%). Ranking of these components in order of importance yielded largely similar results. Moreover, respondents indicated disclosing the etiology of the cognitive diagnoses to patients 86.9% of the time (SD = 19.5%).

Figure 4. Most Important Components of Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n = 181).

Note: 1= Discussing recommendations; 2= Answering questions about results; 3= Discussing diagnosis/differential; 4= Discussing/explaining test results; 5= Discussing implications of results for daily functioning; 6= Ensuring understanding of results and diagnosis; 7= Discussing implications of results in the context of referral questions/presenting concerns; 8= Validating concerns/providing reassurance; 9= Discussing referrals for diagnostic decision making or further care; 10= Socializing/building rapport; 11= Providing an overview of the session; 12= Other; 13= Reviewing referral information; 14= Dealing with disagreement; Multiple responses were allowed; therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Perceived Barriers to Successful Feedback.

The most common perceived barriers to the successful delivery of feedback are presented in Figure 5. The top three most common barriers were limited patient cognitive ability to understand feedback (74.4%) and disagreement about evaluation results or conclusions by the patient (64.5%) or family members (43.0%). Feeling unsure about the cause of the patient’s presenting concerns (30.2%) and struggling to simplify one’s language when communicating feedback (27.9%) were less common barriers. One-fifth of the sample (21.5%) reported other common barriers such as time constraints, scheduling difficulties, patient no-shows or late arrivals, and technological difficulties associated with telehealth appointments. Once respondents selected their top three most common barriers to successful feedback, they ranked them from most to least important, which was largely consistent with initially reported frequencies.

Figure 5. Perceived Barriers to Successful Delivery of Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n = 172).

Note. 1= Patient having limited cognitive ability to understand feedback; 2= Disagreement with evaluation results/conclusions by patient; 3= Disagreement with evaluation results/conclusions by family; 4= Unsure of the cause of patient’s presenting concerns; 5= Struggling to simplify language used to communicate feedback; 6= Other; 7= Language barrier; 8= Unable to adequately answer the referral question; 9= Feeling inadequately trained in the provision of feedback; Multiple responses were allowed; therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Perceived Strategies that Lead to Successful Feedback.

The most common techniques/strategies used during feedback sessions to assist with the successful communication of NAF are presented in Figure 6. The three most commonly endorsed strategies include simplifying information (60.3%), followed by creating a therapeutic atmosphere (58%), and making feedback conversational (53.4%). Delivering feedback in a direct manner (44.8%) and using metaphors (33.3%) were also endorsed by a sizeable proportion of participants. Ranking of the importance of these techniques yielded largely consistent results with initially reported frequencies.

Figure 6. Techniques/Methods/Strategies/Approaches Used in Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions that Aid in the Successful Delivery of Feedback (n = 174).

Note. 1= Simplifying information; 2= Creating a therapeutic atmosphere; 3= Making the feedback session conversational; 4= Delivering results/conclusions in a direct manner; 5= Using Metaphors; 6= Beginning with delivering results that align with their self-view (as opposed to beginning with results/diagnoses that the patient is likely to disagree with); 7= Other; 8= Using humor; 9= Sharing stories; 10= Establishing your credibility; Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Billing and Reimbursement

The majority (92.3%) of respondents indicated that they use neuropsychological testing evaluation current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (96132/96133) for time spent providing verbal NAF sessions. A minority of respondents indicated that they instead utilize other CPT codes including psychotherapy (13.3%), neurobehavioral status exam (6.3%), health and behavior (6.1%), or family psychotherapy (4.4%) codes for time spent providing NAF sessions, indicating that nearly one third of respondents are using codes other than neuropsychological testing evaluation codes.

Fifty-two percent of the respondents reported not being involved in billing/reimbursement matters. Among those involved with billing (n = 85), 49.4% indicated no problems with reimbursement. See Figure 7 for sources of difficulties reported by a minority of respondents. Regarding the “other” responses in Figure 7 (27.1%), noted barriers included difficulties with hospital billing staff, being unsure of which billing codes to use, difficulties splitting codes between secondary and primary insurance, and some Medicare packages only reimbursing a portion of the evaluation. Notably, among respondents who are aware of billing/reimbursement matters, reimbursement difficulties for feedback sessions were reported to occur for only 5.4% of patients seen in clinic.

Figure 7. Barriers to Successful Reimbursement of Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n =85).

Impact of COVID-19-Related Changes to Verbal Feedback to Patients

Impact of the Pandemic on the Mode and Perceived Effectiveness of Feedback.

We asked about any lasting (current) impact that the COVID-19 pandemic may have had on verbal NAF sessions. As shown in Figure 8a, the majority of respondents indicated that changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic currently have a minimal negative or null impact on the perceived effectiveness of NAF. Interestingly, about 25% of the sample indicated a positive impact.

Figure 8. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Perceived Effectiveness of Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions and Shift to Telehealth.

a. Extent to which COVID-19 Related Changes Currently Impact Effectiveness of Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n =181)

Note. 1= completely (negative impact); 2= substantially (negative impact); 3= moderately (negative impact); 4= minimally (negative impact); 5= not at all; 6= minimally (positive impact); 7= moderately (positive impact); 8= substantially (positive impact); 9= completely (positive impact).

b. Extent to which the COVID-19 Pandemic has Led to a Shift Toward Using Telehealth for Feedback Sessions (n =181)

Note. 1= not at all; 2= minimally; 3= moderately; 4= substantially; 5= completely.

c. Extent to which Shifting to Telehealth due to the COVID-19 Pandemic has Impacted Effectiveness of Feedback Sessions (n =164)

Note. 1= completely (negative impact); 2= substantially (negative impact); 3= moderately (negative impact); 4= minimally (negative impact); 5= not at all; 6= minimally (positive impact); 7= moderately (positive impact); 8= substantially (positive impact); 9= completely (positive impact).

See Figures 8b and 9 for information on the reported shift to telehealth due to the pandemic. About a third of the sample reported shifting primarily to telehealth feedback (38%) due to the pandemic. However, others also reported initially changing their practice but reverting back to their pre-pandemic practice style (36.3%).“Other” responses mostly indicated that telehealth is now an option if patients prefer. Respondents tended to indicate that there was minimal negative (33.5%) or null impact (31.7%) in the effectiveness of feedback sessions following a shift to telehealth. Collectively, about 31% of the sample reported some kind of positive impact (see Figure 8c).

Figure 9. Permanent Changes to Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic (n =179).

Note. 1= Shift to primarily written feedback; 2= shift to primarily telehealth feedback; 3= Initially changed my feedback practice in response to the pandemic, but reverted back to my previous practice style; 4= Other; Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Impact of the Pandemic on Frequency of Feedback.

Most (86.7%) respondents reported no increase or decrease in the number of sessions provided. Similarly, most participants (78.9%) indicated no significant impact on the amount of time spent providing feedback sessions.

Written Feedback to Patients

Frequency of Written Feedback to Patients

Results showed that 80.3% of our sample (n = 147) provide written feedback to patients after their evaluation is completed. Among the remainder of the sample (n = 36) who reported that they do not provide written feedback to any patients, 44.4% indicated that this is due to only providing verbal feedback. However, most (n = 24; 66.7%) selected an “other” response, nearly all (92%) indicating that a copy of the report is provided via the medical chart. Thus, it seems that some respondents may have misunderstood our meaning of “written feedback,” as they appeared to not consider the report as written feedback. Therefore, the overall frequency of providing written feedback is likely greater than the previously reported 80.3%. Among the individuals who reported that they do provide written feedback to patients, written feedback is provided to 89.2% (SD = 24.5) of patients on average. The most common reason for not providing written feedback to some patients (n = 46) was providers sometimes only providing verbal feedback (56%), only providing feedback to the referral (34.8%), or reviewing results with an interdisciplinary team (21.7%)

Modality of Written Feedback

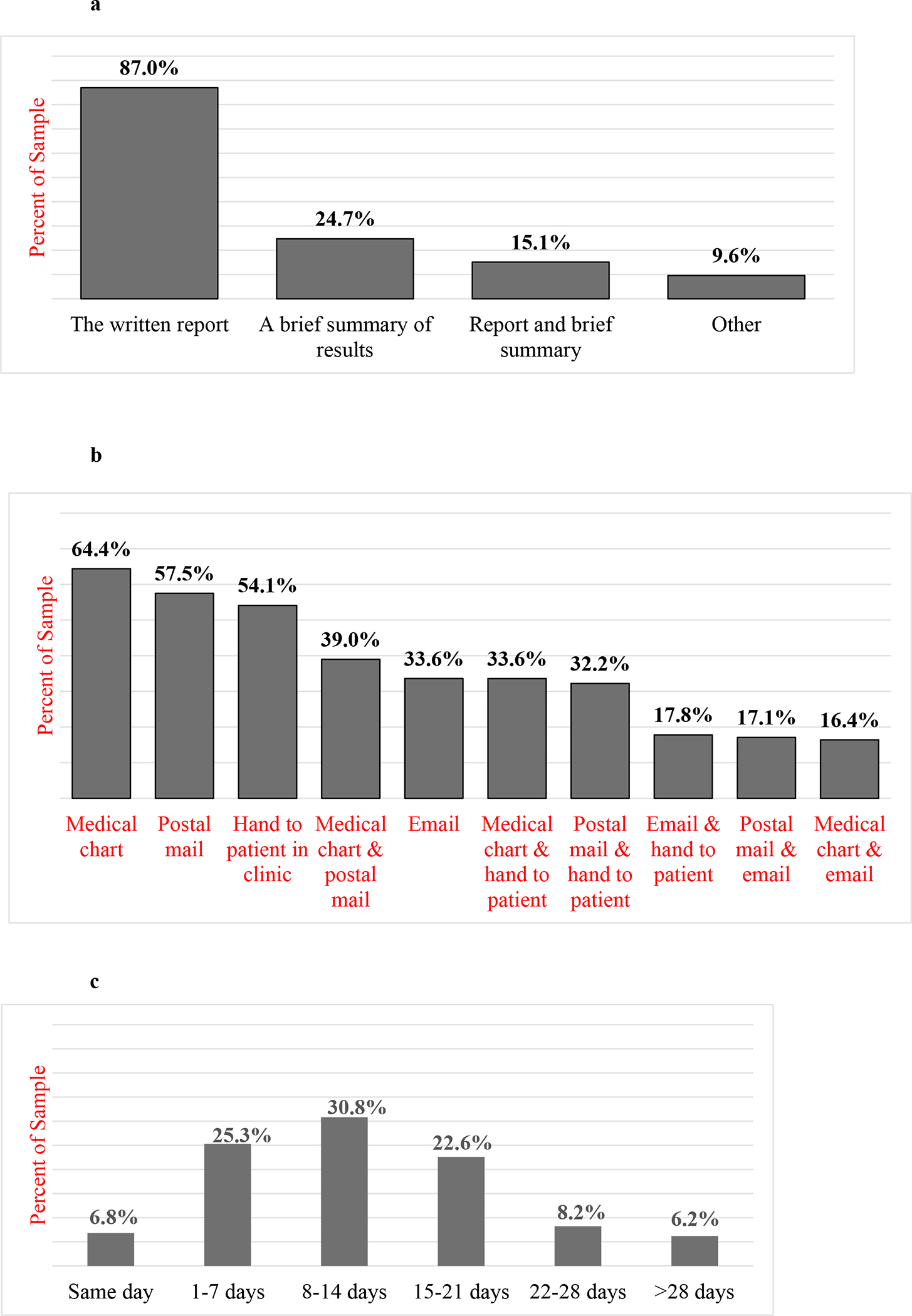

The written report is the primary format in which written feedback is provided (87.0%). A brief summary of results is provided by 24.7% of respondents, while 15.1% reported providing both the report and a separate written summary (see Figure 10a). Over half of respondents reported uploading written feedback (copy of report or written summary) to the medical chart (64.4%), delivering via postal mail (57.5%), or handing it to the patient in clinic (54.1%; see Figure 10b). Respondents also communicate with patients via written methods (such as email) after feedback sessions to answer questions 11.8% of the time (SD = 21.3).

Figure 10. Modality and Timing of Delivering Written Feedback to Patients.

a. Format in which Written Feedback is Primarily Provided (n = 146)

Note. Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

b. Method of Delivering Written Feedback to Patients (n = 146)

Note. Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

c. Length of Time After Testing Until Written Feedback is Provided (n = 146)

Timing of Written Feedback

The most frequent length of time until written feedback is provided to patients was 8–14 days (30.8%), though 1 to 7 days (25.3%) and 15 to 21 days after testing (22.6%) were endorsed similarly. Nearly 15% of the sample reported taking longer than 3 weeks (see Figure 10c).

Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources

Frequency of Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources

54.4% of our sample (n = 99) provide verbal feedback to referral sources. Of the 83 respondents who indicated that they do not provide verbal feedback to any referral sources, most reported this being due to only providing written feedback to referrals (79.5%; see Figure 11a). Among the 99 respondents who indicated that they do provide verbal feedback to referring providers, verbal feedback is provided to 27.8% (SD = 24.8) of their cases on average. Reasons for sometimes not providing verbal feedback to referring providers varied (see Figure 11b), with the most common reason being only providing written feedback to referrals (68.1%).

Figure 11. Reasons for not Providing Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources.

a. Reasons for not Providing Verbal Feedback to All Referral Sources (n = 83)

Note. Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

b. Reasons for Sometimes not Providing Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources (n = 94)

Note. Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Modality of Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources

Respondents reported that on average, they provide verbal feedback to referring providers over the phone 51.9% of the time on average, in-person 29.4% of the time, and via televideo 18.6% of the time (see Figure 12a).

Figure 12. Modality and Timing of Verbal Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback to Referral Sources.

a. Percent of the Time Various Modalities are Used for Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources (n = 98)

b. Length of Time After Testing Until Verbal Feedback is Provided to Referral Source (n = 97)

Note. SD (in person) = 35.2; SD (phone) = 39.9; SD (televideo) = 30.6.

Timing of Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources

On average, respondents reported spending 10.9 minutes (SD = 5.5) providing verbal feedback to referring providers per case. About half of respondents reported providing verbal feedback to referring providers within one week of the completion of the evaluation (49.5%), while 23.7% reported providing feedback 8–14 days after testing (see Figure 12b).

Written Feedback to Referral Sources

Frequency of Written Feedback to Referral Sources

Results showed that 92.3% of respondents (n = 167) reported providing written feedback to referring providers. These respondents reported that written feedback is provided to 95.9% of cases on average. The top reason for not providing written feedback to providers was only providing feedback to patients (n = 17), and nine participants reported sometimes only providing verbal feedback to referrals.

Modality of Written Feedback to Referral Sources

Results showed that 100% of those who reported delivering written feedback to referring providers deliver written feedback via the assessment report, while 21% reported providing a brief summary of results, and 21% reported providing both the report and a written summary (see Figure 13a). Most of the sample (84.7%) upload the report to the medical chart, while a smaller portion of respondents provide written feedback to providers via email (27%) or postal mail (23.3% see Figure 13b).

Figure 13. Modality and Timing of Delivering Written Feedback to Referral Sources.

a. Format in which Written Feedback is Primarily Provided to Referral Sources (n = 167)

Note. Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

b. Method of Delivering Written Feedback to Referral Sources (n = 163)

Note. Multiple responses were allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

c. Length of Time After Testing Until Written Feedback is Provided to Referral (n = 146)

Timing of Written Feedback to Referral Sources

Nearly all respondents give written feedback to referring providers within three weeks, with 33.5% giving feedback within one week, 32.3% giving feedback between 8 to 14 days, and 19.8% giving feedback 15 to 21 days after the evaluation (see Figure 13c).

Training in Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback

The majority of respondents reported that their graduate coursework either minimally prepared (48.9%) or did not prepare (36.1%) them to provide feedback (see Figure 14). Most respondents indicated that they received minimal (44.4%) to moderate (31.1%) preparation in providing feedback at the practicum level of training. At the internship level, most respondents reported minimal (23.9%), moderate (34.4%), or substantial preparation (33.9%). During postdoctoral training, most respondents reported moderate (20.6%), substantial (39.4%), or complete preparation (24.4%).

Figure 14. Extent to which Various Stages of Training Prepared Respondents to Provide Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n = 180).

Respondents were also asked to indicate the top three most helpful methods by which they learned to provide NAF sessions (see Figure 15). They indicated that live observation of supervisors (89.1%), providing feedback under supervision (85.7%), and direct instruction from supervisors (52%) were the most helpful. Data on ranking these methods from most to least helpful aligned with frequencies reported above. The last survey question asked respondents to indicate any resources that they would recommend learning more about conducting NAF sessions. Of the 98 manually entered responses, 83 respondents (84.7%) recommended Feedback That Sticks (Postal & Armstrong, 2013) and five respondents recommended any resources by the late Karen Postal, including her books or podcast at the INS conference. Other recommended books included In Our Clients’ Shoes (Finn, 2007) and Validity Assessment in Clinical Neuropsychological Practice (Schroeder & Martin, 2021).

Figure 15. Most Helpful Methods Throughout Training to Learn to Provide Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback Sessions (n = 175).

Note. 1= Live observation of supervisors; 2= Providing feedback under supervision; 3= Instruction/direct education from supervisors; 4= Self-teaching without guidance; 5= Assigned reading; 6= Role playing; 7= Lectures; 8= Other; 9= Teaching videos; Multiple responses allowed, therefore percentages sum to greater than 100%.

Discussion

Verbal Feedback to Patients

Nearly all respondents (98.4%) provide verbal feedback sessions to all (92.3%) of their patients. The most common reason for not providing feedback involved patients declining the offer. These rates are somewhat higher than those from prior studies, which reported that 77% to 92% of respondents provide assessment feedback to patients (Curry & Hanson, 2010; Smith et al., 2007; Sweet et al., 2020). It is unsurprising that rates of feedback provision are quite high, given current APA standards for providing feedback.

Most neuropsychologists use a combination of modalities to provide feedback sessions across clinical cases. The most common was in-person feedback (56%), a frequency lower than the findings of Smith et al. (2007) (71.3%), which occurred before telehealth was as commonplace as it is today. Neuropsychologists in our sample reported spending about 45 minutes per feedback session. This length of time is similar to that reported in Smith et al. (2007), which indicated an average of 50 to 60 minutes.

Our results also showed that most neuropsychologists provide feedback sessions within three weeks after assessment completion, though this timeline depends on whether the neuropsychologist is providing clinical supervision (which seems to delay feedback sessions) or whether patients are especially complex. Non-clinical factors also likely influence the time at which feedback is provided. For example, for the patient living far from the clinic but preferring in-person feedback, providing feedback the same day may be beneficial (Postal & Armstrong, 2013). Additionally, some qualitative data from our study indicated that same-day feedback appears to be occasionally provided if there is a concern for safety, if a severe diagnosis can be easily ruled out, or if the patient is highly concerned about their test results. Some respondents also noted that they allow patients to review reports and then decide if they would like to follow up with a feedback session, which tends to delay the time at which feedback is provided. Such an approach could allow for a more collaborative discussion during feedback, as the patient will have had time to read over the report and develop questions (Postal & Armstrong, 2013). Future research could examine the impact of feedback timing on patient outcomes.

Content and Style of Verbal Feedback to Patients

Approaches to feedback with patients and components of feedback sessions varied. Most respondents have the report in-hand or on the computer, so they can walk patients through results and recommendations. An almost equal number of respondents utilize some kind of visual aid, such as a normal/bell curve or graphs/charts of data. While utilization of brain models has been suggested to be one of the most common props used in feedback sessions, with the goal of making concepts as concrete as possible (Postal & Armstrong, 2013), our results indicate that this practice is less common.

Participants reported that the most important components of feedback sessions include discussing recommendations, answering questions about results, discussing diagnoses and test results, discussing implications of results for daily functioning and presenting concerns, and ensuring understanding. Jacobson et al. (2015) found that 91.9% of psychologists make a deliberate effort to ensure that patients understand assessment results. In the current study, ensuring that patients understand results from testing was ranked among the most important components of the NAF session.

The most common perceived barriers to the successful delivery of verbal feedback included patient’s having limited cognitive ability to understand feedback and the patient and family disagreeing with assessment results. When communicating feedback to patients with limited cognitive abilities, assuring that a family member or loved one is listening to and understanding feedback is important. However, considering that some patients do not have a support network, conveying concepts in as concrete and simple manner as possible is also key. Furthermore, literature suggests that managing disagreement or resistance from patients and/or loved ones may be best addressed by establishing rapport and providing a therapeutic space of openness and genuine regard (Gorske & Smith, 2008; Waldron-Perrine et al., 2021). Techniques from motivational interviewing may also be useful in such situations (Miller & Rollnick, 2012).

As noted above, providing feedback to patients with limited cognitive ability to understand the information will likely necessitate conveying information in a simple and direct manner. Considering that many patients seen by neuropsychologists may be cognitively impaired, it is not surprising that one of the approaches endorsed by respondents as most important to successful feedback entails communicating results and conclusions in a direct manner. Medical literature suggests that successful communication with patients requires uncomplicated language, minimization of jargon, avoiding vagueness, and utilizing repetition (King & Hoppe, 2013). These findings also align well with principles of communication by Heath and Heath (2008), who emphasize the importance of simplifying information by reducing information to key points and communicating in a concrete manner. Surprisingly, two core communication strategies suggested by Heath and Heath (2008), use of stories and establishing credibility, were the least two frequently endorsed strategies among our respondents.

Billing and Reimbursement

The most common codes used to bill for feedback sessions were neuropsychological testing codes. However, it is important to note that about 30% of our sample also reported use of other codes for NAF sessions (e.g., psychotherapy, family psychotherapy, neurobehavioral status exam, and health behavior codes), which may reflect inappropriate CPT code use. According to prior research, 34.2% of neuropsychologists who provide feedback to patients and who are involved in the billing process experience difficulties billing for feedback sessions (Sweet et al., 2020). Our findings yielded a lower proportion (21.8%). Difficulties with reimbursement appeared to be caused by coverage and reimbursement issues related to working with an insurance provider. Thus, a goal of our professional organizations might be to advocate for better insurance coverage for neuropsychological services. Additionally, it may be beneficial for institutions to provide their neuropsychologists with education regarding correct billing and coding practices.

Impact of COVID-19-Related Changes to Verbal Feedback to Patients

The majority of respondents believe that the COVID-19 pandemic had a minimally negative or null impact on the effectiveness of NAF. Most respondents have shifted at least some of their verbal feedback sessions to a virtual format, which has not been perceived to negatively impact session effectiveness. Given that recent literature argues for the validity and satisfaction of teleneuropsychological assessment (Brearly et al., 2017; Parks et al., 2021), virtual NAF (Turner et al., 2012), telehealth psychotherapy (Greenwood et al., 2022), and other telehealth interventions (Butzner & Cuffee, 2021), it is not surprising that our sample reported little to no impact on the perceived effectiveness of feedback.

Written Feedback to Patients

Most respondents in our sample (80.3%) reported providing written NAF to patients. Another 11% of our sample reported that they provide a copy of the report or make the report available in medical records, despite reporting that they do not provide written feedback. Thus, the true percentage of our sample that provides written NAF is closer to 90%. Reasons for not providing written NAF mostly included only providing verbal feedback to patients or only providing feedback to referring providers. This rate is notably higher than the 43% to 63% rate reported in prior studies (Smith et al., 2007; Curry & Hanson, 2010; Jacobson et al., 2015). Findings may indicate an increasing prevalence of providing written feedback over time.

Most respondents (87%) reported that written NAF is delivered in the form of the written report, while about 25% reported that a brief written summary is provided, and about 15% reported providing both. Considering that prior work suggests that summaries increase later recall of clinical recommendations (e.g., Fallows & Hilsabeck, 2013), increasing the frequency of providing summaries to patients may prove beneficial for patient’s adherence to recommendations. Contrary to our observed results, Curry and Hanson (2010) showed that a larger portion their sample of psychologists provided a written summary to patients. This discrepancy may suggest that general psychologists emphasize delivering written feedback via summaries, while neuropsychologists tend to provide written feedback via the written report.

The majority of respondents reported providing written NAF within 3 weeks of the completion of the evaluation, with very few providing written NAF the same day as completion of the evaluation, or greater than 3 weeks. There may be pros and cons to the times at which written NAF is provided. For example, some respondents in our study noted that they prefer to wait to finalize the report until after the feedback session to allow for modification of the report to include information that came to light during the feedback session. While this approach helps to ensure accuracy and consistency in the report, it is possible that providing feedback weeks after testing may decrease patient satisfaction with neuropsychological services and may hinder the referring provider’s ability to integrate neuropsychological findings in treatment planning in a timely manner.

Verbal Feedback to Referral Sources

About half (54.4%) of our sample reported that they provide verbal NAF to referring providers (for 27.8% of cases on average). Most of the 99 respondents who indicated that they do not provide verbal NAF to referrals indicated that they only provide written NAF to referrals. Generally, respondents indicated that they tend to provide verbal feedback only for cases that require additional care coordination, for cases that are time-sensitive, or if the provider is in the same interdisciplinary team. In contrast, Smith and colleagues (2007) reported that 87.1% of their sample directly discuss feedback with referring providers for at least some cases. They also found that members of SPA were more likely to discuss results with referring providers compared to members of NAN/INS, who were more likely to mail reports to referrals (Smith et al., 2007). These findings may stem from neuropsychology’s historical role as a fairly independent consult service within healthcare settings, wherein there is limited in-person interaction with other providers; although, modern neuropsychological practice has certainly become more integrated (Glen et al., 2019; Kubu et al., 2016).

Respondents typically are providing verbal NAF to referring providers within two weeks after testing, mostly via phone call. These interactions are reportedly brief, lasting about 11 minutes, likely due to the time constraints of physicians and other providers. Indeed, clear and concise communication that prioritizes key points of the case is important when working interdisciplinarily (Postal & Armstrong, 2013), and is central to the SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) model for healthcare communication (Shahid & Thomas, 2018).

Written Feedback to Referral Sources

Nearly all respondents (92.3%) reported providing written NAF to referring providers (for 95.9% of cases on average). Several additional respondents indicated that they do not provide written NAF to referrals but described providing the report via EMR, indicating that the true number of respondents who provide written NAF to referrals is greater than 92.3%. All respondents who provide written NAF reported that it is provided via the neuropsychological assessment report, while some provide a brief summary, or both. Written feedback is mostly delivered via EMR, although fax is often used. This feedback is most commonly provided within three weeks after assessment completion. The high rate of provision of written feedback to referral sources is encouraging, considering an American College of Physicians report indicating that up to 50% of referrals are not completed (American College of Physicians, n.d.). This closing of the referral loop ensures that patients can have neuropsychological evaluation findings integrated into their referring providers’ approach to treatment.

Training in Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback

The final section of the survey covered preparation to provide NAF sessions. Results indicated that training in how to deliver feedback generally increases throughout major stages of training. Specifically, participants reported that minimal or no preparation is provided in graduate coursework, minimal to moderate preparation is provided during practicum experiences, minimal to substantial preparation is provided during internship, and moderate to complete preparation is provided during postdoctoral training. However, it should be noted that even at the postdoctoral level, about 14% of respondents indicated minimal preparation. As pointed out by Smith et al. (2007), there is a striking discrepancy between the known importance and value of providing feedback to patients (e.g., Gruters et al., 2022) and the lack of training provided. This finding is particularly surprising given that the Houston Conference Guidelines indicate that provision of feedback is an important competency in clinical neuropsychology (Hannay et al., 1998). These findings are not unique to neuropsychology. Curry and Hanson (2010) found that about one third of their sample of psychologists reported receiving very little or no training in feedback prior to internship and during internship, while nearly half reported very little or no training during postdoctoral training.

Reportedly, the most helpful methods for learning to provide feedback sessions included live observation of supervisors, providing feedback under supervision, direct instruction from supervisors, and self-teaching without guidance. Similarly, Jacobson et al. (2015) reported that among psychologists who routinely provide feedback, learning to provide feedback was primarily done via self-teaching. Curry and Hanson (2010) also reported that their respondents primarily learned to provide feedback via self-instruction. These concurrent findings across studies argue strongly that graduate curriculum and training adaptations must be made to provide comprehensive training in the provision of feedback sessions. Such training may involve offering structured NAF didactics, guided readings, role play exercises, and live observations. Of note, while other methods of learning to provide feedback sessions, such as lectures and teaching videos, were among the least frequently endorsed, this finding may be attributable to lack of experience with these methods throughout training, rather than a belief that these methods themselves are unhelpful.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, our study had limited representation of pediatric neuropsychologists. Survey feedback indicated that questions may have been easier to answer for adult, rather than pediatric or lifespan neuropsychologists likely because survey questions did not differentiate between providing feedback to patients (i.e., children in the context of pediatric evaluations) and parents/family/caregivers. It is important to highlight this limitation, as pediatric neuropsychologists often provide feedback to parents and caregivers and provide feedback less consistently to patients (i.e., children). This limitation may have resulted in pediatric neuropsychologists disproportionally choosing not to complete or dropping out of the survey and may also have resulted in pediatric neuropsychologists reporting practices that are not completely reflective of their actual approach to feedback. Therefore, results of this study may not accurately reflect feedback practices of pediatric and lifespan neuropsychologists.

Second, our sample consisted of mostly White women from clinical PhD programs. While these demographics are somewhat consistent with previous research that has surveyed psychologists and neuropsychologists (i.e., Jacobson et al., 2015; Sweet et al., 2020), further study of feedback practices in specific subgroups of neuropsychologists would be welcome. Additionally, it is important to highlight that our sample size is relatively small compared to field-wide surveys of clinical neuropsychologists, which have included as many as 1,677 participants (e.g., Sweet et al., 2020). It was difficult to estimate the response rate for this survey and the extent to which we reached an adequate number of practicing neuropsychologists with the opportunity to participate. We could not access data on listserv membership numbers of all sources used to send the survey, and to our knowledge, none of the listervs keep data on the demographic and professional characteristics of their listserv members. Furthermore, we advertised the study via social media, and it was impossible to precisely estimate the number of practicing neuropsychologists who may have been reached via this method. Our best guess is that we provided an opportunity for several thousand currently practicing neuropsychologists to participate and therefore had a fairly low response rate. As a result, the sample collected likely consists of a unique group that is interested in neuropsychological feedback and motivated to participate in research on this topic. Thus, our sample may not be reflective of the neuropsychological profession nationwide. Relatedly, it is important to note that due to asking specific questions about billing practices, we restricted our sample to individuals practicing in the United States. As such, further study of neuropsychological feedback practices among practitioners in other countries will be important.

Third, as indicated in the results of written feedback to patients and written feedback to referral sources, some respondents seemed to have not considered the neuropsychological report as “written feedback”. Though we took steps to clearly operationalize “written feedback” as including the report at the outset of the survey, this definition could have been made more visually obvious.

Fourth, given the length of the survey, we did not include questions inquiring about demographics of typical patients. This step could have allowed for analysis of feedback practices based on various patient populations. Additionally, considering that different patient populations (i.e., epilepsy, dementia, brain injury, stroke, neurodevelopmental, non-enlgish speaking populations, pediatric, adult, etc.) can play an influential role on whether NAF is provided and the way in which it is provided, it will be important for future research on NAF to investigate this important variable.

Finally, our survey was descriptive in nature and did not assess the relationship between feedback and patient outcomes. Rigorous controlled trials of NAF practices are necessary to determine feedbacks styles, contents, and modalities that lead to the best patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The current study is the first to comprehensively survey clinical neuropsychologists in the United States about neuropsychological assessment feedback practices. Results provide better understanding of how the field of neuropsychology utilizes specific approaches to feedback, structures feedback sessions, collaborates with referring providers, adapts services when needed (e.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic), and bills for feedback services. Furthermore, findings yielded some surprising results about how clinical neuropsychologists view their training experiences to prepare for providing feedback as potentially inadequate. Thus, we advocate for training programs to increase the quality and frequency of coursework, observation, and clinical supervision of feedback sessions across all stages of training. Of course, accomplishing this goal requires development of an evidence-base for NAF practice; as such, rigorous controlled trials are seriously needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge that our research follows in the footsteps of Karen Postal, Ph.D., ABPP-CN, who recently passed away. She contributed substantially to the neuropsychological assessment feedback literature and the field of neuropsychology at large.

Funding

Disclosure

Internal funding from the University of Missouri-Columbia was used to provide compensation for survey respondents’ time (i.e., $5 Amazon e-gift card). Additionally, Cady Block receives book royalties from APA Publishing. Andrew Kiselica has a grant from the National Institute on Aging IMPACT Collaboratory (UC401) that funds his research time.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The view, opinions and/or findings contained in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official position, policy or decision of the University of Missouri, Regent University, Cleveland Clinic, or Emory University.

References

- American College of Physicians (n.d.). Closing-the-loop. Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative.

- American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2003, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). https://www.apa.ord/ethics/code/

- Board of Directors (2007). American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) practice guidelines for neuropsychological assessment and consultation. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21, 209–231. 10.1080/13825580601025932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearly TW, Shura RD, Martindale SL, Lazowski RA, Luxton DD, Shenal BV, & Rowland JA (2017). Neuropsychological test administration by videoconference: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 27, 174–186. 10.1007/s11065-017-9349-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzner M, & Cuffee Y (2021). Telehealth interventions and outcomes across rural communities in the United States: Narrative Review. JMIR Internet Research, 23. 10.2196/29575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry KT, & Hanson WE (2010). National survey of psychologists’ test feedback training, supervision, and practice: A mixed methods study. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92, 327–336. 10.1080/00223891.2010.482006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donders J (2016). Neuropsychological report writing. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fallows RR, & Hilsabeck RC (2013). Comparing two methods of delivering neuropsychological feedback. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 28, 180–188. 10.1093/arclin/acs142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE (2007). In our clients’ shoes: Theory and techniques of therapeutic assessment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fujji D (2016). Conducting a culturally informed neuropsychological evaluation. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Glen ET, Hostetter G, Ruff RM, Roebuck-Spencer TM, Denney RL, Perry W, Fazio RL, Garmoe WS, Bianchini KJ, & Scott JG (2019). Integrative care models in neuropsychology: A National Academy of Neuropsychology Education Paper. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 34, 141–151. 10.1093/arclin/acy092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorske TT, & Smith SR (2008). Collaborative therapeutic neuropsychological assessment. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood H, Krzyzaniak N, Peiris R, Clark J, Scott AM, Cardona M, Griffith R, & Glasziou P (2022). Telehealth versus face-to-face psychotherapy for less common mental health conditions: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mental Health, 9. 10.2196/31780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruters AAA, Ramakers IHGB, Verhey FRJ, Kessels RPC, & Vugt ME (2022). A scoping review of communicating neuropsychological test results to patients and family members. Neuropsychology Review, 32, 294–315. 10.1007/s11065-021-09507-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannay HJ, Bieliauskas LA, Crosson BA, Harmneke TA, Hamsher K.deS, & Koffler SP (1998). Proceedings of the Houston Conference on Specialty Education and Training in Clinical Neuropsychology. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 13, 157–250. 10.1093/arclin/13.2.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD (2012). Clinical applications of neuropsychological assessment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14, 91–99. 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.1/pharvey [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath C, & Heath D (2008). Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KC, & Loring DW (2020). Emory university telehealth neuropsychology development and implementation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34, 1352–1366. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1791960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KC, Block C, Bellone JA, Dawson EL, Garcia P, Gerstenecker A, Gradyan JM, Howard C, Kamath V, LeMonda BC, Margolis SA, McBride WF, Salinas CM, Tam DM, Walker KA, & Del Bene VA (2022). Diverse experiences and approaches to tele neuropsychology: Commentary and reflections over the past year of COVID-19. 10.1080/13854046.2022.2027022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jacobson RM, Hanson WE, & Zhou H (2015). Canadian psychologists’ test feedback training and practice: A national survey. Canadian Psychology, 56, 394–404. 10.1037/cap0000037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King A, & Hoppe RB (2013). “Best Practice” for patient-centered communication: A narrative review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5, 385–393. 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00072.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubu CS, Ready RE, Festa JR, Roper BL, & Pliskin NH (2016). The times they are changin’: Neuropsychology and integrated care teams. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 30, 51–65. 10.1080/13854046.2015.1134670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, & Tranel D (2012). Neuropsychological Assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin PK, & Schroeder RW (2021). Feedback with patients who produce invalid testing: Professional values and reported practices. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35, 1134–1153. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1722243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, & Mark MM (1995). Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychology, 14, 101–108. 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd Ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parks AC, Davis J, Spresser CD, Stroescu I, Ecklund-Johnson E (2021). Validity of in-home teleneuropsychological testing in the wake of COVID-19. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 00, 1–10. 10.1093/arclin/acab002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg PO, Auerbach SM, Seel RT, Buenaver LF, Kiesler DJ, & Plybon LE (2005). The impact of patient-centered information on patients’ treatment satisfaction and outcomes in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50, 366–374. 10.1037/0090-5550.50.4.366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Postal K & Armstrong K (2013). Feedback that sticks: The art of effectively communicating neuropsychological assessment results. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder RW, & Martin PK (2021). Validity assessment in clinical neuropsychological practice: Evaluating and managing noncredible performance. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid S, & Thomas S (2018). Situation, background, assessment, recommendation (SBAR) communication tool for handoff in health care – A narrative review. Safety in Health, 4, 1–9. 10.1186/s40886-018-0073-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Wiggins CM, & Gorske TT (2007). A survey of psychological assessment feedback practices. Assessment, 14, 310–319. 10.1177/1073191107302842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet JJ, Klipfel KM, Nelson NW, & Moberg PJ (2020). Professional practices, beliefs, and incomes of U.S. neuropsychologists: The AACN, NAN, SCN 2020 practice and “salary survey”. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35, 7–80. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1849803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapuria A, Porat T, Kalra D, Dsouza G, & Xiaohui S, & Curcin V (2021). Impact of patient access to their electronic health record: Systematic review. Informatics for health and social care, 46, 194–206. 10.1080/17538157.2021.1879810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TH, Horner MD, Vankirk KK, Myrick H, & Tuerk PW (2012). A pilot trial of neuropsychological evaluations conducted via telemedicine in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 18, 662–667. 10.1089/tmj.2011.0272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron-Perrine B, Rai JK, & Chao D (2021). Therapeutic assessment and the art of feedback: A model for integrating evidence-based assessment and therapy techniques in neurological rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation, 49, 293–306. 10.3233/NRE-218027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.