Abstract

Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7 nAChR) is an ion-gated calcium channel that plays a significant role in various aspects of cancer pathogenesis, particularly in lung cancer. Preclinical studies have elucidated the molecular mechanism underlying α7 nAChR-associated lung cancer proliferation, chemotherapy resistance, and metastasis. Understanding and targeting this mechanism are crucial for developing therapeutic interventions aimed at disrupting α7 nAChR-mediated cancer progression and improving treatment outcomes. Drug research and discovery have determined natural compounds and synthesized chemical antagonists that specifically target α7 nAChR. However, approved α7 nAChR antagonists for clinical use are lacking, primarily due to challenges related to achieving the desired selectivity, efficacy, and safety profiles required for effective therapeutic intervention. This comprehensive review provided insights into the molecular mechanisms associated with α7 nAChR and its role in cancer progression, particularly in lung cancer. Furthermore, it presents an update on recent evidence about α7 nAChR antagonists and addresses the challenges encountered in drug research and discovery in this field.

Keywords: α7 nAChR, antagonist, cancer progression, lung cancer

Lung cancer continues to be a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide in 2023.1 It remains the most common cause of cancer-related deaths and the second most prevalent cancer, in terms of new cases in the United States. Lung cancer is mainly classified into two types based on pathological features: non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for approximately 85% of cases, and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), comprising approximately 15% of all cases.2 The prognosis for metastatic lung cancer remains poor, with a survival rate of <4%, despite advancements in diagnostic markers and therapeutic options.3 Moreover, therapeutic resistance is often observed, causing unsatisfactory clinical outcome.4,5 Smoking continues to be a significant risk factor that is strongly associated with increased lung cancer and mortality rates although lung cancer can occur in nonsmokers due to varying factors such as air pollution.6

Currently, several efforts are ongoing to identify novel molecular targets and develop small molecules for lung cancer treatment. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) have been recognized as potential therapeutic targets for lung cancer for over a decade, as smoking, which is a major cause of lung cancer, involves the binding of nicotine and its derivatives to nAChRs, contributing to cancer pathogenesis.7,8 Accumulative studies have demonstrated significant nAChR expression, particularly alpha7 (α7) nAChR, in lung cancer cells, alongside their presence in neuron tissues.7,9,10 The nAChR family comprises diverse α and β subtypes combinations, exhibiting distinct expression patterns in specific tissues.11,12 Among these subtypes, α7 nAChR has been identified as a major contributor to lung cancer aggressiveness, influencing increased proliferative, chemotherapy resistance, and metastasis.13−15 Importantly, α7 nAChR has been identified as a potential prognosis marker, correlating with poor overall survival in patients with lung cancer.16 Targeting or inhibiting this receptor holds promise as an intriguing strategy for suppressing lung cancer pathogenesis.17,18

Therefore, this comprehensive literature review aimed to explore the molecular mechanisms of α7 nAChR in lung cancer. This review provides an update on the current development of its antagonists and addresses the challenges associated with drug discovery in this field. We aim to enhance our understanding of α7 nAChR and its potential as a therapeutic target by exploring these aspects, ultimately paving the way for improved interventions in lung cancer treatment.

Expression of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (nAChR) in Lung Cancer

The expression of α7 nAChR is generally abundant in neuronal tissues, where it plays a crucial role in neurotransmitter transmission between neurons.19 Dysregulation of α7 nAChR has been implicated in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, causing impaired memory persistence and cognitive dysfunction.20−22 The nAChR family consists of various pentameric α and β subunits with a tissue-specific expression variation. Assembly of different pentamers causes various nAChR subtypes, each with distinct pharmacological functions due to varying binding affinities for specific ligands.23 Binding of exogenous nicotine and its derivatives, such as 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N-nitrosonornicotine (NNN), as well as endogenous acetylcholine, stimulates calcium influx, thereby increasing intracellular calcium levels and activating multiple signaling pathways in cancer cells.24

Each nAChR subunit consists of an extracellular domain, four transmembrane helices, and a hydrophilic intracellular loop.25 Several alpha (α3−α7, α9) and beta (β2−β4) subunits have been identified in lung cancers.7,26,27 These subunits are encoded by CHRNA3, CHRNA4, CHRNA5, CHRNA6, CHRNA7, CHRNA9, CHRNB2, CHRNB3, and CHRNB4 genes. The CHRNA7 gene, which encodes the α7 subunit, is increased in patients with SCLC who are smokers compared to those with NSCLC when comparing different lung cancer subtypes.7 Conversely, the expression of α6β3 nAChRs was associated with smokers with NSCLC, while α4β4 nAChRs were significantly elevated compared to normal lung tissue.26 NSCLC cell lines have shown the expression of α3−α5, α7, α9, α10, and β2–β4 nAChR subunits, with notable α3β4 nAChR upregulation compared to normal cell lines.27 Furthermore, the involvement of genetic variants of nAChRs in lung cancer has been reported. Notably, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified within the 15q24–15q25.1 region of the CHRNA3/CHRNB4/CHRNA5 gene cluster. These genetic variations are significantly associated with an elevated risk of developing lung cancer.28−30 Additionally, the amplification of copy number variations (3956) within the CHRNA7 gene has also been linked to the pathogenesis of lung cancer and is correlated with a poor overall survival rate.8

Notably, a high nAChR expression level has been significantly correlated with decreased overall survival in patients with lung cancer.16 Nicotine has been shown to predominantly mediate α7 nAChR expression, acting through the Sp1/GATA protein and E2F1 pathway.15,31,32 Furthermore, various evidence has indicated the involvement of α7 nAChR in oncogenic activities associated with lung cancer. The activation of this receptor by nicotine has been shown to stimulate cancer cell proliferation and metastasis,14,33,34 emphasizing the potential of α7 nAChR as a therapeutic target for lung cancer. Additionally, α7 nAChR antagonists, either in the form of synthetic molecules or natural compounds, have significantly helped in suppressing such aggressive characteristics,15,35,36 thereby suggesting that inhibiting its function or expression could offer a promising therapeutic strategy.

Molecular Mechanisms of α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor in Lung Cancer

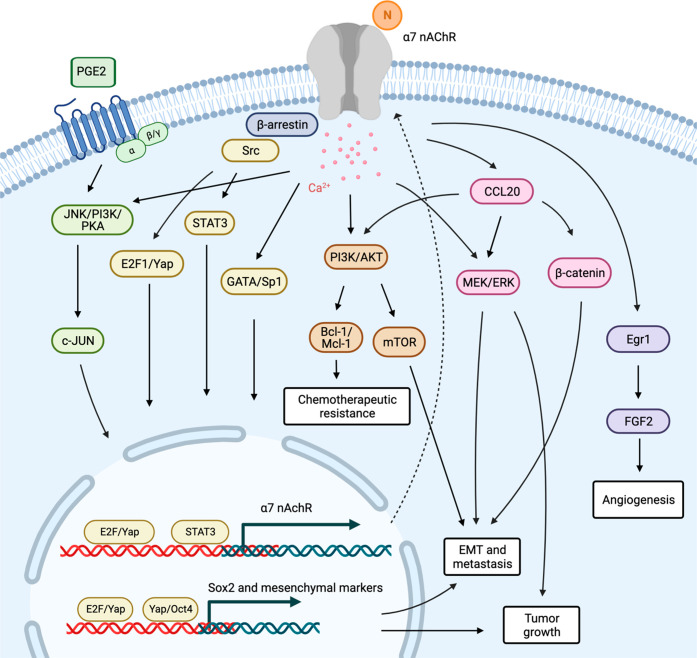

Mechanistic investigations have elucidated the molecular signaling events that occur upon α7 nAChR activation in cancer. Upon binding of ligands to the α7 nAChR, a conformational shift occurs in its intracellular domain, resulting in the opening of calcium channels. This leads to a surge in calcium influx and initiates signal transduction pathways closely associated with cancer progression (Figure 1). Research has indicated that the upregulation α7 nAChR expression, which is induced by cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), promotes in vitro NSCLC cell growth through the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and protein kinase A (PKA) signaling activation.37 Conversely, RNA interference targeting α7 nAChR effectively inhibits PGE2-induced cell proliferation, indicating the existence of crosstalk between prostanoids and cholinergic signaling pathways. AKT signaling pathway plays a central role in lung cancer progression.38,39 Nicotine treatment has been shown to stimulate the expression of phosphorylated-AKT (p-AKT) and phosphorylated-ERK (p-ERK), and this effect was notably counteracted by α-bungarotoxin (α-btx), which is a competitive irreversible α7 nAChR antagonist, indicating the AKT/ERK signaling involvement.40 Additionally, α7 nAChR blockade by α-btx or downregulation of its expression significantly attenuated nicotine-mediated in vitro NSCLC cell proliferation and in vivo xenograft growth in nude mice.13 Treatment with an α7 nAChR antagonist reduced phosphorylated MEK (p-MEK) and p-ERK levels because of the well-established role of MEK/ERK pathway in promoting cancer proliferation,41 indicating that MEK/ERK signaling acts as a downstream cascade of α7 nAChR in tumor growth regulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the molecular mechanism underlying the association between the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) and cancer progression. N; nicotine and its derivatives (created using Biorender.com).

Apoptosis deregulation and chemotherapeutic resistance pose significant challenges in drug discovery and new drug development. Dysfunctions in cell death signaling and the overactivation of cell survival molecules are commonly observed in lung cancer.4,42 Lung cancer has demonstrated the ability to acquire resistance mechanisms through various pathways even with the advent of targeted therapies.4,43 Intriguingly, serum from smokers can enhance resistance to erlotinib (an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and cisplatin-induced lung cancer cell death by activating AKT signaling.44−46 An increased antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression generally plays a crucial role in apoptotic resistance.47,48 Nicotine has been reported to stabilize Bcl-2 by preventing its degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway, thereby reducing sensitivity to cisplatin in lung cancer cells.49 Furthermore, nicotine-induced AKT activation causes antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 phosphorylation, which promotes its antiapoptotic activity by inhibiting the pro-apoptotic protein Bak.50 This phenomenon contributes to the chemotherapy resistance. The antagonist of α7 nAChR, APS8, which is a synthetic alkylpyridinium polymer, induces mitochondrial depolarization and promotes apoptosis in lung cancer cells in vitro.35 Notably, studies have demonstrated that blocking or downregulating α7 nAChR increases the sensitivity to chemotherapy-induced cell death in various cancers, including cisplatin in oral cancer cells,51 taxans in gastric cancer cells,52 and sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells.53

Lung cancer metastasis, which is a leading cause of high mortality rates, is associated with a 5-year survival rate of <4%.3 Metastasis involves a series of sequential processes, beginning with cell migration and invasion from the primary tumor, accompanied by extracellular matrix degradation.54 Angiogenesis induction and new blood vessel formation facilitate cancer cell circulation, thereby establishing secondary tumors. Current or previous smoking has been reported to cause an increased risk of metastasis.55 NNK, which is a nicotine-derivative, has upregulated the chemokine CCL20 in patients with lung cancer, both in secretion in vitro and in vivo.56 CCL20, in turn, promotes cancer cell growth and metastasis through the ERK/AKT/STAT3 signaling pathway. NNK has enhanced lung cancer cell motility via AKT signaling, and the downregulation of α7 nAChR expression by provitamin A carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin (BCX) attenuates this cancer behavior.36 Furthermore, the antagonist of α7 nAChR, QND7, has demonstrated a suppressive effect on AKT and its downstream target mTOR in lung cancer,17 emphasizing the role of AKT/mTOR in α7 nAChR regulation in cancer metastasis.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays an essential process involved in cancer metastasis, characterized by a change in cellular morphology from an epithelial to a mesenchymal phenotype. This transition is accompanied by the upregulation of specific transcription factors and genes that facilitate cellular metastasis.57 Research has revealed that α7 nAChR activation by nicotine plays a role in mediating the EMT process through the MEK/ERK signaling pathway. However, this effect can be inhibited by an antagonist targeting this receptor.13,14 Nicotine has stimulated self-renewal phenotypes and promoted EMT in lung cancer cells by inducing the expression of embryonic stem cell transcription factors, particularly Sox2, through α7 nAChR activation in the context of lung cancer.58 Src plays a significant role in the regulation of stemness properties.59 Upon binding to α7 nAChR, Src kinase was subsequently activated, thereby regulating Sox transcription factors such as E2F1 and Yap1. Besides lung cancer, α7 nAChR was also associated with nicotine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and the expression of binding immunoglobulin protein via the AKT/YAP/TEAD signaling pathway.60 The activation of this axis promotes EMT in oral cancer.

Angiogenesis, which is the formation of new blood vessels, is recognized as a crucial process for lung cancer survival and metastasis. Angiogenesis provides necessary nutrients and oxygen to support cancer cell growth and facilitate their dissemination to distant sites.61 Blocking α7 nAChR has an inhibitory effect on nicotine-mediated vascularization both in vitro and in vivo.62 Furthermore, nicotine has enhanced the upregulation of angiogenic growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), which is suppressed by selective α7 nAChR by reducing the level of binding of transcription factor Egr-1 to the FGF2 promoter. These findings collectively indicate that α7 nAChR may serve as a potential therapeutic target for lung cancer.

The Development of α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonists

Alpha7 nAChR antagonists are classified into two categories: naturally derived ligands (Table 1) and synthetic chemical ligands (Table 2). These antagonists can function as competitive or noncompetitive agents, which bind to orthosteric or allosteric sites, respectively.

Table 1. Naturally Derived Ligands Acting as α7 nAChR Antagonists for Lung Cancera.

| compound | nAChR activity (affinity and functional assays) | anticancer activity | molecular mechanism | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| methyllycaconitine (MLA) | hα7: IC50 = 2 nMb | inhibiting proliferation and migration, inducing apoptosis | ↑ Bax/Bcl-2 | (71,95) |

| ImI and ImII (derived from α-conotoxin [α-ctx]) | ImI | no data | no data | (96) |

| hα7: IC50 = 595 nM;b hα4β2: IC50 > 10 μM;b hα3β4: IC50 = 3.39 μM;b rα1β1δε: IC50 > 10 μMb | ||||

| ImII | ||||

| hα7: IC50 = 571 nM;b hα4β2: IC50 > 10 μM;b α3β4: IC50 > 10 μM;b rα1β1δε: IC50 = 1.06 μMb | ||||

| α-bungarotoxin (α-btx) | hα7: IC50 = 5.6 nM;b hα9/α10: IC50 = 9.7 nM;b rα1β1δε: IC50 = 14.0 nMb | suppressing cell invasion and migration | ↓ c-Src/PKCι/FAK | (97) |

| α-cobratoxin (α-cbt) | hα7: Ki = 13–105 nM;c IC50 = 2.8–4.1 nM;b hα9/α10: IC50 = 7.9 nM;b rα1β1δε: IC50 = 1.3 nMb | apoptosis and necrosis induction, and suppressing in vivo tumor growth | ↓ survivin, ↓ xiap, ↓ IAP1, ↓ IAP2, ↓ Bcl-XL | (89−91,97−99) |

| SLURP-1 | hα7: not compete [125I]-α-bungarotoxin;c IC50 = 1 μM for rSLURP-1;b hα3β4: IC50 = 4.75 μM for synthetic SLURP-1b | inducing cell cycle arrest, inhibiting cell migration | ↓ p-PTEN, ↓ p-mTOR, ↓ p-PDGFRβ | (85,100,101) |

| ws-Lynx1 | hα7: IC50 = 50 μMb | inhibiting cell proliferation, and inducing cell cycle arrest | ↑ p-p53, ↑ PKC/IP3 | (94,102) |

h: human; r: rat; Ki: inhibition constant; IC50: inhibitory concentration at 50%.

Electrophysiology of nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Radioligand analysis: inhibition of [125I]-α-bungarotoxin in transfected cell line GH4C1

Table 2. Current Synthetic Ligands Acting as α7 nAChR Antagonistsa.

h: human; Kd: dissociation constant; KA: antagonist dissociation constant); IC50: inhibitory concentration at 50%. Electrophysiology of nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

FRET-based calcium sensor of nAChRs expressed in HEKtsA201 cells.

Radioligand analysis: inhibition of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine in nAChRs expressed in HEKtsA20, HEK293, or SH-EP1 cells

Radioligand analysis: inhibition of [125I]-α-bungarotoxin and [3H]-(±)-epibatidine in chick brain

Radioligand analysis: inhibition of [125I]-α-bungarotoxin in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells

Structure and Binding Sites of α7 nAChR

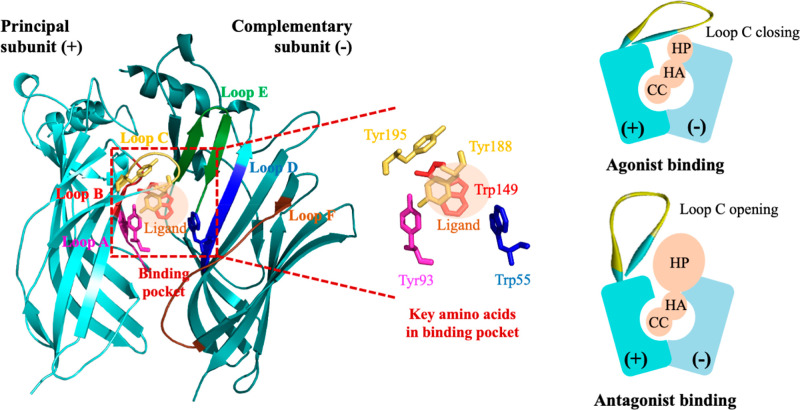

Alpha7 nAChR is a homopentameric receptor belonging to the Cys-loop superfamily, which can be structurally divided into three domains: an extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain.25 The orthosteric ligand binding site of the receptor is located between the subunit interfaces, spanning from loop A to F within the extracellular domain.25 Aromatic amino acids use these loops to create an aromatic cage, forming a binding pocket primarily composed of tyrosine and tryptophan (Figure 2). Additionally, adjacent cysteines located at the tip of loop C significantly contributes to ligand binding, closing, and opening in response to agonist and antagonist binding to the receptors.63 Notably, an allosteric site exists in a distinct region; however, it has not been definitively identified. This allosteric site could be located in either the extracellular domain or the transmembrane domain of the nAChR.

Figure 2.

α7 nAChR orthosteric binding pocket and pharmacophore of α7 nAChR ligands. CC: cationic center; HA: hydrogen bond acceptor; HP: hydrophobic part.

Essential Pharmacophore and Properties Required to Suppress α7 nAChR

Nowadays, the development of selective α7 nAChR antagonists remains limited, particularly in the case of naturally derived ligands. Most of these ligands act as allosteric modulators, which makes pharmacophore identification harder compared to that of synthetic chemical ligands that exhibit competitive antagonistic functions. However, the pharmacophore among them remains the same due to the shared binding sites between orthosteric α7 nAChR antagonists and agonists. This pharmacophore includes a basic amine protonated at physiological pH for cation−π interaction, a hydrophobic aromatic part for π–π interaction, and a linker that acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor (Figure 2).64 Peng et al. reported that hydrogen bonds, π–π interactions, and hydrophobic interactions are important binding interactions for α7 nAChR antagonists.65 Further, they identified specific amino acid residues involved in the interaction with the antagonist from in silico systems, such as Tyr93, Lys143, Trp147, Tyr188, and Tyr195 in the principal subunit as well as Trp55 and Leu118 in the complementary subunit. The most crucial residues for antagonist recognition were Ty93, Trp147, and Tyr188 in the principal subunit, as determined by site-directed α7 nAChR mutagenesis.65

Orthosteric α7 nAChR antagonists and agonists share the same binding pocket has caused the discovery of small molecules that act as α7 nAChR antagonists through derivatization or structure modification of agonist compounds.64 The nitrogen atom with a positive charge and the hydrogen bonds are retained in the structure in these modifications.66,67 However, the hydrophobic part is modified to increase steric hindrance by introducing an aromatic moiety that can potentially engage in π–π stacking with the binding pocket.66,68 This steric hindrance causes loop C opening, which impedes calcium ion influx through α7 nAChR (Figure 2).

Clinically approved α7 nAChR antagonists for lung cancer treatment remain unavailable despite the evidence supporting the use of α7 nAChR inactivation as a promising strategy for treating cancer. However, some α7 nAChR antagonists have demonstrated anticancer activity in vitro and in preclinical studies, thereby generating interest in developing this class of ligands as potential antilung cancer drugs.

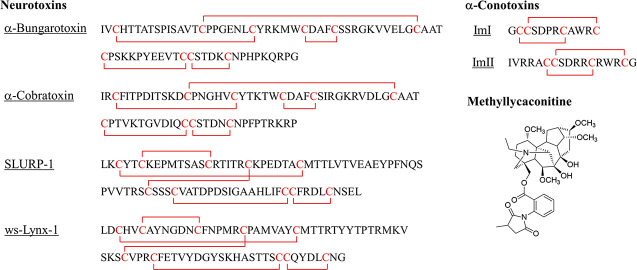

Naturally Derived Ligands

Natural ligands have gained attention as potential α7 nAChR antagonists due to their strong binding affinity, effectively inhibiting α7 nAChR function. However, their irreversible binding, immunogenicity, and high systemic toxicity limit their suitability as therapeutic agents.69 Therefore, finding α7 nAChR antagonists with high specificity and minimal side effects is crucial for drug development. Examples of naturally derived ligands include methyllycaconitine (MLA), α-conotoxin (α-ctx), α-bungarotoxin (α-btx), α-cobratoxin (α-cbt), secreted human Ly-6/uPAR-related protein 1 (SLURP-1), and Ly-6/neurotoxin 1 (Lynx1) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structure of the α7 nAChR antagonists.

MLA is a potent and selective α7 nAChR antagonist derived from Delphinium and Aconitum. It effectively blocks the function of α7 nAChR agonists and has demonstrated the ability to attenuate nicotine-induced proliferative effects in lung cancer cells.70,71 MLA can abrogate the effect of nicotine in mediating cancer cell migration in a hepatocyte growth factor-dependent manner.72 Researchers have attempted to modify MLA’s structure, such as making modifications at the nitrogen atom and ester side chain, as well as creating simple bicyclic MLA analogs. However, these modifications have caused reduced potency, noncompetitive inhibition, and lack of selectivity.71,73

As α7 nAChR antagonists, α-ctxs derived from cone snail venom74 show promise in blocking closely related nAChR subtypes, including α7, α4β2, and α3β4 nAChRs.75 Certain α-ctxs, such as ImI and RegIIA, have exhibited potent α7 nAChR inhibition with nanomolar range IC50 values.76 Additionally, mutations of native α-ctxs, such as PnIA, ArIB, TxIB, and LvIB (Figure 3), have enhanced their binding affinity.77 Moreover, α-ctx ImI application in a drug delivery system, where IMI is modified micelles loaded with docetaxel, has shown potential in enhancing the intracellular uptake of anticancer drugs in α7 nAChR-overexpressed NSCLCs.78 Nevertheless, the precise biological pathways underlying the action of these compounds remain elusive.

A member of the Ly-6 protein family found in snake venom, α-btx, can block various types of nAChRs, including muscle and neuronal types. However, it is not suitable for clinical use although it is an important compound for studying and differentiating nAChR subtypes.79 α-btx primarily interacts with a conserved residue of loop C in α7 nAChR through cation-π interaction and hydrogen bonding.80 α-btx can attenuate NNK-activated c-Src/PKCι/FAK, thereby suppressing lung cancer cell migration and invasion.81 Interestingly, studies have revealed that α-btx has no effect on lung cancer cell growth without nicotine stimulation,82 although α7 nAChR knockdown can decrease lung cancer cell growth. This indicates the involvement of nonion channel signaling of α7 nAChR in cancer growth,82 since it has reported intracellular metabotropic functions of this receptor in several cell types including lung cancer cells.83−85

Neurotoxins, Ly-6 proteins found in snake venom, can be categorized as long-chain and short-chain toxins.86 Long-chain neurotoxins can bind to both muscular type and neuronal α7 nAChR,87 whereas short-chain neurotoxins selectively bind to the muscular type.69,86,88 One example is α-cbt, which is a long-chain neurotoxin derived from the snake Naja kaouthia, which acts as a high-affinity α7 nAChR antagonist. The effectiveness of α-cbt in suppressing tumor growth in mice is limited,89 but it has shown potential in affecting cell viability and tumor growth in NSCLC90 and mesothelioma90,91 by downregulating antiapoptotic proteins, indicating the need for alternative options.

Another natural ligand of interest is SLURP-1, which is a paracrine regulator with structural similarities to three-finger snake α-neurotoxins that interact with α7 nAChR, covering the orthosteric binding site. Electrostatic interactions stabilize the interactions between recombinant SLURP-1 (rSLURP-1) and loop C in the principal subunit, while hydrophobic interactions are observed between rSLURP-1 and the complementary subunit.92 SLURP-1 acts as an allosteric α7 nAChR modulator and has been associated with decreased lung adenocarcinoma cell viability, potentially involving α7 nAChR, epidermal growth factor receptors, and β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR). The signaling pathways associated with SLURP-1, such as PI3K-AKT, and downstream effectors, such as IP3 receptors and STAT3 transcription factors, indicate a metabotropic signaling mechanism.93

Lynx1, which is another member of the Ly-6 protein family, acts as a negative allosteric modulator of nicotinic signaling in the lung. It interacts with various nAChR subtypes, including α7, α4β2, and α6 nAChRs.94 Lynx1 is an endogenous lung cancer growth regulator, and its expression in lung cancer cells has been found to decrease cell proliferation via activating function of tumor suppressor p53, emphasizing the potential therapeutic value of small molecule mimetics of Lynx1 in lung cancer.82

Synthetic Chemical Ligands

The synthetic chemical molecules acting as α7 nAChR antagonists are usually discovered through structural α7 nAChR agonist modifications. Therefore, the agonist pharmacophore, which consists of a cationic center, a hydrogen bond acceptor, and a hydrophobic part, exists in the antagonist binding at the orthosteric pocket site. The antagonist activities of these molecules are typically lower than those of the above-mentioned naturally derived ligands, but their safety profiles are better due to their improved α7 nAChR selectivity. The limited number of selective α7 nAChR antagonist molecules has increased the need to develop novel antagonists. Nowadays, several scaffolds, such as piperidine-spirooxadiazole, piperidine, quinuclidine triazole-based, stilbene, quinoline, nicotine, phenothiazine, alkylpyridinium polymer, and phenylguanidine scaffolds have been developed as α7 nAChR antagonists. They demonstrated a role in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis in lung cancers.

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening was employed to discover piperidine-spirooxadiazole derivatives, as mentioned regarding the pharmacophore shared between α7 nAChR agonists and antagonists. The information obtained from the T761–0184 modification indicates that the size and electronegativity of the substituents, particularly the presence of p-bromophenyl and electron-donating groups substituted in the biaryl moiety of spiroxazole, are crucial for the α7 nAChR antagonist properties. The modified compounds exhibit IC50 ranging from 3.3 to 13.7 μM against α7 nAChR. Compound B10, which demonstrates IC50 values of 5.4 μM for α7 nAChR and 32 μM for α4β2 nAChR when tested using the two-electrode voltage clamp assay, is an example of a compound derived from this technique.64 However, no studies on these compounds have been conducted concerning lung cancer.

A new series of 1-[2-(4-alkoxy-phenoxy-ethyl)]piperidines and 1-[2-(4-alkoxy-phenoxy-ethyl)]-1-methylpiperidinium iodides have been reported as α7 nAChR antagonists. The most potent compound in this series is compound 12a, which can inhibit 50% of ion currents elicited by choline in interneurons from the stratum radiatum hippocampal CA1 area at 5 μM. The presence of a quaternary amine in the structure mediated cation-π interaction with the α7 nAChR binding pocket, as observed during molecular docking and MD simulation, leading to the highest potency in inhibiting rat hippocampal α7 nAChR.67 Only the activity against α7 nAChR was reported, without information about lung cancer activity.

Another compound discovered during α7 nAChR agonist optimization is QND7,66 which is a quinuclidine triazole-based molecule. It antagonizes α7 nAChR competitively and noncompetitively at a micromolar level. Interestingly, QND7 induced apoptosis in H460 and A549 NSCLC cell lines, comparable to cisplatin. The IC50 values for H460 and A549 are 75.40 and 76.29 μM, respectively. It can suppress proliferation and lung cancer cell migration, revealing its potential as an antimetastasis agent, which is a concerning issue in patients with lung cancer. The anticancer effects of QND7 are attributed to the decreased Akt/mTOR activity, which are downstream signaling molecules of α7 nAChR-mediated lung cancer progression. QND7 demonstrates several promising profiles for lung cancer treatment, but improving its potency and selectivity remains necessary.17

The stilbene scaffold is currently studied for its function in antagonizing α7 nAChR and its antiangiogenic activity in SCLC. MG624 can suppress nicotine-induced proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner, showing a maximum activity at 20 μM. MG624 can reduce nicotine-induced angiogenic tubule formation in primary human microvascular endothelial cells of the lung (HMEC-Ls) by approximately 40% in terms of angiogenesis activity. It also causes a 5-fold reduction in nicotine-induced angiogenic sprouting of ex vivo rat aortic rings. MG624 demonstrated the suppression of angiogenesis in H69 human SCLC tumors in vivo, in both the chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) and the nude mice models, without any changes or toxicity in animals. The antiangiogenic effect of MG624 was mediated by nicotine-induced FGF2 production suppression via the Egr-1 pathway.62 The structure of MG624 was further modified with an ammonium head and a styryl portion to obtain compound 33, which is the most potent and has the highest selectivity to α7 nAChR in the series (0.82 nM Ki and 1.07 μM IC50). Its antagonistic effect aligns with an open-channel block mechanism, which still requires further supportive experimentations.103 However, the lung cancer activity of modified MG624 has not been evaluated.

Dequalinium chloride, which is an antiseptic drug with a quinoline scaffold, is a nonselective antagonist. It can partially irreversibly bind to ACh with the IC50 value of 120 nM, as tested via patch clamp recording in stably α7 nAChR-transfected HEK293 cells with 300 μM acetylcholine chloride and 10 μM PNU-120596. Slightly higher IC50 values were observed in calcium dye fluorescence measurements of CHO-K1 cells that are stably transfected with α7 nAChR, as well as in confocal imaging of individual cells using GCAMP7s-CAAX, which is a calcium-sensitive protein reporter. The anticancer effect of dequalinium chloride was studied in glioma cells and promyelocytic leukemia, where it exhibited growth inhibition and induced apoptosis. These anticancer effects are mediated by antagonizing α7 nAChR, in addition to its antimitochondrial activity.104

A multivalent ligand of nicotine was also developed as an α7 nAChR antagonist. Divalent and heptavalent nicotine derivatives with varying ethylene glycol lengths and cyclodextrin cores were synthesized and evaluated for antagonist properties. Among this series, compound 2 showed the highest potency, indicating that the spacer length of the divalent structure affected the α7 nAChR antagonist effect.105,106

Several compounds act as noncompetitive α7 nAChR antagonists and do not contain all the pharmacophoric features, indicating their binding sites outside the orthosteric binding pocket. In particular, N3,N7-diaminophenothiazin-5-ium derivatives, which contain a phenothiazine ring, can reversibly antagonize α7 nAChR. This was tested via electrophysiology in Xenopus oocytes injected with cRNA of hα7 nAChR, and it occurs in a noncompetitive manner, as the EC50 value of ACh remains unchanged. These derivatives may block ion flux and inhibit the conformational transition of channels.106 However, their anticancer activity remains unexplored. Another example is BCX, which is an oxygenated carotenoid. BCX pretreatment at 1 and 10 mg/kg diet before NNK injection reduced NNK-induced lung tumor formation by 52% and 63%, respectively. BCX suppressed α7 nAChR expression in both BEAS-2B and A549 cells as well as PI3K-mediated phosphorylation and phosphorylation of ERK1/2, which is a direct downstream molecule of α7 nAChR. BCX inhibited lung tumorigenesis and cancer cell motility through α7 nAChR/PI3K signaling downregulation, independent of its provitamin A activity. APS8, which is an analog of a polymer from the marine sponge Haliclona sarai, also inhibited α7 nAChR in a noncompetitive manner at nanomolar concentrations. The IC50 was approximately 1 nM, as tested using Xenopus oocytes expressing α7 nAChR.36 APS8 inhibited NSCLC tumor cell growth and activated apoptotic pathways. The IC50 for A549 cells was 375 nM in the MTT assay and 362 nM in SkMES-1 cells. However, no effect was observed in lung fibroblast cell line MRC-5, even at a 1 μM concentration. APS8 exposure up-regulated several pro-apoptotic proteins while down-regulating antiapoptotic proteins in both A549 and SKMES-1 cells.35 APS8 impaired the viability of A549 cells with an EC50 of 1.7 μM. LD50 of APS8 was intravenously administered in BALB/c mice at 6 mg/kg. Tumor growth was delayed by approximately 22.5 days without any toxic side effects when intratumoral APS8 injection was administered at 4 mg/kg. No APS8 resistance was observed, even with repetitive intratumoral injections. The histological analysis of tumor sections treated with APS8 demonstrated a different pattern compared to the above-mentioned compounds, with necrosis being the predominant route of cell death. APS8 can also block α4β2 nAChR, although its affinity for α7 nAChR is high.69 Together with, MD-354 and compound 12, its N-methyl analogue containing a novel phenyl guanidine scaffold, were reported as noncompetitive α7 nAChR antagonists.107,108 In the rat brain, compound 12 can compete [125I]-bungarotoxin in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamic mammillary nuclei, that express α7 nAChR.107 However, the modification barely increases the α7 nAChR potency.

Moreover, indinavir, which is an approved drug for noncancer diseases, can exhibit α7 nAChR antagonist effects. Indinavir, which is an antiviral drug acting as a protease inhibitor, acts as a α7 nAChR antagonist at concentrations of >10 μM, whereas it functions as a positive allosteric modulator at concentrations of <10 μM. However, the effect of this compound on cancer remains to be proven because it can act on α7 nAChR, MMP-2, and MMP-9, which are correlated with cancer metastasis.109

Some synthetic chemical ligands acting as α7 nAChR antagonists have been derived from the simplified structure of naturally derived ligands. A ring E analogue and a ring AE-bicyclic analogue of MLA were synthesized and modified in terms of ester and nitrogen side-chain.110 All of them demonstrated antagonistic properties; however, they exhibited less potency than MLA. In addition, analogue 16, which showed the highest potency, also reduced ACh response to 53.2%, compared to 3.4% for MLA. However, further development is still required.71

Other molecules have been shown to target α7 nAChR expression besides being antagonist to α7 nAChR. One example is GW1929, which is a proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) ligand. It inhibits α7 nAChR expression in NSCLC cell lines, such as A549, H358, H522, and H1792, through p38 MPAK activation and PI3K/mTOR inactivation. The α7 nAChR expression reduction occurs at the transcriptional level via Egr-1 protein expression induction and the binding activity of Egr-1 to a specific DNA region in the α7 nAChR gene promoter.111 Sinomenine, which is originally used for rheumatoid arthritis treatment, is another example. It exhibits antitumor effects in several cancers, including breast cancer, lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and gastric cancer. This compound downregulates the α7 nAChR expression level through a feedback pathway of α7 nAChR/ERK/Egr-1, thereby inhibiting macrophage M1 polarization.112−115 Sinomenine decreases the positive modulator SP-1 and TTF-1 levels, whereas it increases the negative modulator Egr-1 levels in lung cancer A549 cells. The phosphorylation of ERK, which is a major upstream signaling molecule regulating α7 nAChR expression, is weakened by sinomenine. Hence, sinomenine can reduce cancer cell migration, induce apoptosis, and decrease the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and tumor growth factor-beta levels in the serum.18

Challenges and Perspectives

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved α7 nAChR antagonist for cancer treatment remains unavailable despite nearly three decades of nAChR drug development. One crucial issue is the discovery of selective ligands that can effectively target α7 nAChR without interacting with other nAChR subtypes. The challenge lies in the fact that nAChR subtypes share some similarities in their amino acid sequences and the existence of numerous nAChR subtypes. This similarity, coupled with the species-specific pharmacological properties of nAChRs, poses a significant challenge for investigating α7 nAChR antagonists specific to the human receptor.116

Furthermore, the availability of multiple nAChR subtypes expressed by each cancer cell further complicates the search for suitable models to test potential compounds.116 The absence of selective ligands capable of consistently confirming binding adds to the challenges of the α7 nAChR drug development.

Another major concern in developing α7 nAChR antagonists is limited data access. The published information regarding α7 nAChR ligands fails to adequately state or characterize the functional activity of the compounds, particularly in the case of patented ligands, in many cases.117

Expanding on the topic, it is crucial to address the significance of overcoming these challenges to advance α7 nAChR drug development. Researchers can pave the way for potential breakthroughs in cancer treatment by identifying selective ligands that can effectively target α7 nAChR and developing reliable models to test compounds. Additionally, promoting transparency in reporting functional activity data for α7 nAChR ligands is essential for the scientific community to evaluate and replicate findings accurately.

Conclusions

A significant increase in α7 nAChR expression has been widely acknowledged in lung cancer cases exhibiting aggressive characteristics. Nicotine and its derivatives, present in tobacco, have been reported to enhance the α7 nAChR expression and stimulate its function. Consequently, this initiates downstream signaling cascades that are implicated in tumor growth, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance. Numerous efforts have been undertaken to explore novel compounds derived from natural sources or chemical synthesis. The core structures of these compounds have been identified, and various modifications have been implemented. Approved specific antagonists for clinical use remain unavailable despite the recognition of α7 nAChR as a promising therapeutic target for lung cancer. This is primarily due to the challenges associated with achieving selectivity, potency, and safety profiles. Overcoming these challenges remains a key focus for ongoing drug research and development aimed at comprehensively improving these concerns.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- α7 nAChR

Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- α-btx

Alpha-bungarotoxin

- α-cbt

Alpha-cobratoxin

- α-ctx

Alpha-conotoxin

- β-AR

Beta-adrenergic receptors

- AKT

Protein kinase B

- CCL20

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 20

- E2F1

E2F transcription factor 1

- Egr1

Early growth response 1

- EMMPRIN/CD147

Extracellular inducer of matrix metalloproteinase

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FGF2

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- GATA

GATA-binding protein

- IP3

Inositol trisphosphate

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- Lynx1

Ly-6/neurotoxin 1

- MEK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MLA

Methyllycaconitine

- MMP-2

Matrix metalloproteinase-2

- MMP-9

Matrix metalloproteinase-9

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NNK

4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- NNN

N-Nitrosonornicotine

- NSCLC

Nonsmall cell lung cancer

- PDFGRβ

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta

- PGE2

Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin E2

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- PPARγ

Proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homologue

- RECK

Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich proteins with kazal motifs

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SCLC

Small-cell lung cancer

- SLURP-1

Secreted human Ly-6/uPAR-related protein 1

- Sox2

SRY-Box transcription factor 2

- Sp1

Specificity protein 1

- Src

Src kinase

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TEAD

TEA domain transcription factor

- TIMP-1

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1

- TIMP-2

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- Yap1

Yes-associated protein 1

Author Contributions

K.A. and V.P. researched data, performed an extensive literature survey, substantially contributed to the content of this article, and drafted the manuscript. O.V. and Y.H. revised the manuscript and provided advice. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript before submission.

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand under Molecular Probes for Imaging Research Network (NRCT: N10A650046).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Siegel R. L.; Miller K. D.; Wagle N. S.; Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. Ca-Cancer J. Clin 2023, 73 (1), 17. 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura K. Lung Cancer: Understanding Its Molecular Pathology and the 2015 WHO Classification. Front Oncol 2017, 7, 193. 10.3389/fonc.2017.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar J.; Urban D.; Amit U.; Appel S.; Onn A.; Margalit O.; Beller T.; Kuznetsov T.; Lawrence Y. Long-Term Survival of Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer over Five Decades. J. Oncol 2021, 2021, 1. 10.1155/2021/7836264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Du Y.; Wen R.; Yang M.; Xu J. Drug Resistance to Targeted Therapeutic Strategies in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2020, 206, 107438. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. W.; Gore I.; Okimoto R. A.; Godin-Heymann N.; Sordella R.; Mulloy R.; Sharma S. V.; Brannigan B. W.; Mohapatra G.; Settleman J.; Haber D. A. Inherited Susceptibility to Lung Cancer May Be Associated with the T790M Drug Resistance Mutation in EGFR. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37 (12), 1315–1316. 10.1038/ng1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barta J. A.; Powell C. A.; Wisnivesky J. P. Global Epidemiology of Lung Cancer. Annals of Global Health 2019, 10.5334/aogh.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordas A.; Cedillo J. L.; Arnalich F.; Esteban-Rodriguez I.; Guerra-Pastrián L.; de Castro J.; Martín-Sánchez C.; Atienza G.; Fernández-Capitan C.; Rios J. J.; Montiel C. Expression Patterns for Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Genes in Smoking-Related Lung Cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8 (40), 67878. 10.18632/oncotarget.18948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Lu X.; Qiu F.; Fang W.; Zhang L.; Huang D.; Xie C.; Zhong N.; Ran P.; Zhou Y.; Lu J. Duplicated Copy of CHRNA7 Increases Risk and Worsens Prognosis of COPD and Lung Cancer. Eur. J. Hum Genet 2015, 23 (8), 1019–1024. 10.1038/ejhg.2014.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedillo J. L.; Bordas A.; Arnalich F.; Esteban-Rodríguez I.; Martín-Sánchez C.; Extremera M.; Atienza G.; Rios J. J.; Arribas R. L.; Montiel C. Anti-Tumoral Activity of the Human-Specific Duplicated Form of A7-Nicotinic Receptor Subunit in Tobacco-Induced Lung Cancer Progression. Lung Cancer 2019, 128, 134–144. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer H. K.; Dhar M.; Schuller H. M. Expression of the A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor in Human Lung Cells. Respir. Res. 2005, 6, 29. 10.1186/1465-9921-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata Y.; Miura K.; Yamasaki N.; Ogata S.; Miura S.; Hosomi N.; Kaminuma O. Expression and Function of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Induced Regulatory T Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 (3), 1779. 10.3390/ijms23031779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Madden P.; Gu J.; Xing X.; Sankar S.; Flynn J.; Kroll K.; Wang T. Uncovering the Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Landscape of Nicotinic Receptor Genes in Non-Neuronal Tissues. BMC Genomics 2017, 18 (1), 439. 10.1186/s12864-017-3813-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Yu P.; Zhu L.; Zhao Q.; Lu X.; Bo S. Blockade of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Inhibit Nicotine-Induced Tumor Growth and Vimentin Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer through MEK/ERK Signaling Way. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38 (6), 3309–3318. 10.3892/or.2017.6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Ding X. P.; Zhao Q. N.; Yang X. J.; An S. M.; Wang H.; Xu L.; Zhu L.; Chen H. Z. Role of B7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor in Nicotine-Induced Invasion and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (37), 59199. 10.18632/oncotarget.10498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medjber K.; Freidja M. L.; Grelet S.; Lorenzato M.; Maouche K.; Nawrocki-Raby B.; Birembaut P.; Polette M.; Tournier J. M. Role of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Cell Proliferation and Tumour Invasion in Broncho-Pulmonary Carcinomas. Lung Cancer 2015, 87 (3), 258. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G.; Ji D.; Qu X.; Liu S.; Yang X.; Wang G.; Liu Q.; Du J. Mining and Validating the Expression Pattern and Prognostic Value of Acetylcholine Receptors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Medicine (United States) 2019, 98 (20), e15555. 10.1097/MD.0000000000015555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witayateeraporn W.; Arunrungvichian K.; Pothongsrisit S.; Doungchawee J.; Vajragupta O.; Pongrakhananon V. A7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonist QND7 Suppresses Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration via Inhibition of Akt/MTOR Signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521 (4), 977–983. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S.; Wen W.; Hou X.; Wu J.; Yi L.; Zhi Y.; Lv Y.; Tan X.; Liu L.; Wang P.; Zhou H.; Dong Y. Inhibitory Effect of Sinomenine on Lung Cancer Cells via Negative Regulation of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. J. Leukoc Biol. 2021, 109 (4), 843–852. 10.1002/JLB.6MA0720-344RRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C.; Akmentin W.; Role L. W.; Talmage D. A. Axonal A7* Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Modulate Glutamatergic Signaling and Synaptic Vesicle Organization in Ventral Hippocampal Projections. Front Neural Circuits 2022, 16, 978837 10.3389/fncir.2022.978837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Förster R.; He W.; Liao X.; Li J.; Yang C.; Qin H.; Wang M.; Ding R.; Li R.; et al. Fear Learning Induces A7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor-Mediated Astrocytic Responsiveness That Is Required for Memory Persistence. Nat. Neurosci 2021, 24 (12), 1686. 10.1038/s41593-021-00949-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirttimaki T. M.; Codadu N. K.; Awni A.; Pratik P.; Nagel D. A.; Hill E. J.; Dineley K. T.; Parri H. R. A7 Nicotinic Receptor-Mediated Astrocytic Gliotransmitter Release: Aβ Effects in a Preclinical Alzheimer’s Mouse Model. PLoS One 2013, 8 (11), e81828 10.1371/journal.pone.0081828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacer S. A.; Letsinger A. C.; Otto S.; DeFilipp J. S.; Nikolova V. D.; Riddick N. V.; Stevanovic K. D.; Cushman J. D.; Yakel J. L. Loss of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in GABAergic Neurons Causes Sex-Dependent Decreases in Radial Glia-like Cell Quantity and Impairments in Cognitive and Social Behavior. Brain Struct Funct 2021, 226 (2), 365. 10.1007/s00429-020-02179-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Incamps B. L.; Ascher P. High Affinity and Low Affinity Heteromeric Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors at Central Synapses. J. Physiol. 2014, 592 (19), 4131. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz M.; King J. R.; Yang K.-H. S.; Khushaish S.; Tchugunova Y.; Khajah M. A.; Luqmani Y. A.; Kabbani N. A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Interaction with G Proteins in Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation, Motility, and Calcium Signaling. PLoS One 2023, 18 (7), e0289098 10.1371/journal.pone.0289098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc K.; van Dijk W. J.; Klaassen R. V.; Schuurmans M.; van Der Oost J.; Smit A. B.; Sixma T. K. Crystal Structure of an ACh-Binding Protein Reveals the Ligand-Binding Domain of Nicotinic Receptors. Nature 2001, 411 (6835), 269–276. 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D. C. L.; Girard L.; Ramirez R.; Chau W. S.; Suen W. S.; Sheridan S.; Tin V. P. C.; Chung L. P.; Wong M. P.; Shay J. W.; Gazdar A. F.; Lam W. K.; Minna J. D. Expression of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Genes in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Reveals Differences between Smokers and Nonsmokers. Cancer Res. 2007, 67 (10), 4638. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J.; Liu Y.; Sun Z.; Zhangsun D.; Luo S. Identification of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunits in Different Lung Cancer Cell Lines and the Inhibitory Effect of Alpha-Conotoxin TxID on Lung Cancer Cell Growth. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 865, 172674. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi M. T.; Chatterjee N.; Yu K.; Goldin L. R.; Goldstein A. M.; Rotunno M.; Mirabello L.; Jacobs K.; Wheeler W.; Yeager M.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Lung Cancer Identifies a Region of Chromosome 5p15 Associated with Risk for Adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 85 (5), 679–691. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Qiu F.; Lu X.; Huang D.; Ma G.; Guo Y.; Hu M.; Zhou Y.; Pan M.; Tan Y.; Zhong H.; Ji W.; Wei Q.; Ran P.; Zhong N.; Zhou Y.; Lu J. Functional Polymorphisms of CHRNA3 Predict Risks of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Lung Cancer in Chinese. PLoS One 2012, 7 (10), e46071 10.1371/journal.pone.0046071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone N. L.; Culverhouse R. C.; Schwantes-An T.-H.; Cannon D. S.; Chen X.; Cichon S.; Giegling I.; Han S.; Han Y.; Keskitalo-Vuokko K. Multiple Independent Loci at Chromosome 15q25.1 Affect Smoking Quantity: A Meta-Analysis and Comparison with Lung Cancer and COPD. PLoS Genet 2010, 6 (8), e1001053. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal C.; Chellappan S. Nicotine-Mediated Regulation of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Non-Small Cell Lung Adenocarcinoma by E2F1 and STAT1 Transcription Factors. PLoS One 2016, 11 (5), e0156451. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. C.; Perry H. E.; Lau J. K.; Jones D. V.; Pulliam J. F.; Thornhill B. A.; Crabtree C. M.; Luo H.; Chen Y. C.; Dasgupta P. Nicotine Induces the Up-Regulation of the A7-Nicotinic Receptor (A7-NAChR) in Human Squamous Cell Lung Cancer Cells via the Sp1/GATA Protein Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288 (46), 33049. 10.1074/jbc.M113.501601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Wadei H. A. N.; Al-Wadei M. H.; Schuller H. M. Cooperative Regulation of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma by Nicotinic and Beta-Adrenergic Receptors: A Novel Target for Intervention. PLoS One 2012, 7 (1), e29915. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta P.; Rizwani W.; Pillai S.; Kinkade R.; Kovacs M.; Rastogi S.; Banerjee S.; Carless M.; Kim E.; Coppola D.; Haura E.; Chellappan S. Nicotine Induces Cell Proliferation, Invasion and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in a Variety of Human Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124 (1), 36–45. 10.1002/ijc.23894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zovko A.; Viktorsson K.; Lewensohn R.; Kološa K.; Filipič M.; Xing H.; Kem W. R.; Paleari L.; Turk T. APS8, a Polymeric Alkylpyridinium Salt Blocks A7 NAChR and Induces Apoptosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Mar Drugs 2013, 11 (7), 2574–2594. 10.3390/md11072574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar A. R.; Miao B.; Li X.; Hu K.-Q.; Liu C.; Wang X.-D. β-Cryptoxanthin Reduced Lung Tumor Multiplicity and Inhibited Lung Cancer Cell Motility by Downregulating Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor A7 Signaling. Cancer Prev Res. (Phila) 2016, 9 (11), 875–886. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X.; Fan Y.; Ritzenthaler J. D.; Zhang W.; Wang K.; Zhou Q.; Roman J. Novel Link between Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and Cholinergic Signaling in Lung Cancer: The Role of c-Jun in PGE2-Induced A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Expression and Tumor Cell Proliferation. Thorac. Cancer 2015, 6 (4), 488. 10.1111/1759-7714.12219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iksen; Pothongsrisit S.; Pongrakhananon V. Targeting the Pi3k/Akt/Mtor Signaling Pathway in Lung Cancer: An Update Regarding Potential Drugs and Natural Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4100. 10.3390/molecules26134100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecoy G. A. U.; Chamni S.; Suwanborirux K.; Chanvorachote P.; Chaotham C. Jorunnamycin A from Xestospongia Sp. Suppresses Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Sensitizes Anoikis in Human Lung Cancer Cells. J. Nat. Prod 2019, 82 (7), 1861–1873. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucchietto V.; Fasoli F.; Pucci S.; Moretti M.; Benfante R.; Maroli A.; Di Lascio S.; Bolchi C.; Pallavicini M.; Dowell C.; McIntosh M.; Clementi F.; Gotti C. A9- and A7-Containing Receptors Mediate the pro-Proliferative Effects of Nicotine in the A549 Adenocarcinoma Cell Line. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175 (11), 1957–1972. 10.1111/bph.13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiboonchaiyanan P. P.; Kiratipaiboon C.; Chanvorachote P. Ciprofloxacin Mediates Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes in Lung Cancer Cells through Caveolin-1-Dependent Mechanism. Chem. Biol. Interact 2016, 250, 1–11. 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdar A. F.; Minna J. D. Deregulated EGFR Signaling during Lung Cancer Progression: Mutations, Amplicons, and Autocrine Loops. Cancer Prevention Research 2008, 1, 156. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M.; Okamoto I.; Tsurutani J.; Oiso N.; Kawada A.; Nakagawa K. Clinical Impact of Switching to a Second EGFR-TKI after a Severe AE Related to a First EGFR-TKI in EGFR-Mutated NSCLC. Jpn. J. Clin Oncol 2012, 42 (6), 528–533. 10.1093/jjco/hys042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imabayashi T.; Uchino J.; Osoreda H.; Tanimura K.; Chihara Y.; Tamiya N.; Kaneko Y.; Yamada T.; Takayama K. Nicotine Induces Resistance to Erlotinib Therapy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells Treated with Serum from Human Patients. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11 (3), 282. 10.3390/cancers11030282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R.; Al Khashali H.; Haddad B.; Wareham J.; Coleman K. L.; Alomari D.; Ranzenberger R.; Guthrie J.; Heyl D.; Evans H. G. Regulation of Cisplatin Resistance in Lung Cancer Cells by Nicotine, BDNF, and a β-Adrenergic Receptor Blocker. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 (21), 12829. 10.3390/ijms232112829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petpiroon N.; Bhummaphan N.; Tungsukruthai S.; Pinkhien T.; Maiuthed A.; Sritularak B.; Chanvorachote P. Chrysotobibenzyl Inhibition of Lung Cancer Cell Migration through Caveolin-1-Dependent Mediation of the Integrin Switch and the Sensitization of Lung Cancer Cells to Cisplatin-Mediated Apoptosis. Phytomedicine 2019, 58, 152888 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Shim M. K.; Yang S.; Moon Y.; Song S.; Choi J.; Kim J.; Kim K. Combination of Cancer-Specific Prodrug Nanoparticle with Bcl-2 Inhibitor to Overcome Acquired Drug Resistance. J. Controlled Release 2021, 330, 920–932. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prateep A.; Sumkhemthong S.; Karnsomwan W.; De-Eknamkul W.; Chamni S.; Chanvorachote P.; Chaotham C. Avicequinone B Sensitizes Anoikis in Human Lung Cancer Cells. J. Biomed Sci. 2018, 25 (1), 32. 10.1186/s12929-018-0435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka T.; Luo L. Y.; Shen L.; He H.; Mariyannis A.; Dai W.; Chen C. Nicotine Increases the Resistance of Lung Cancer Cells to Cisplatin through Enhancing Bcl-2 Stability. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110 (7), 1785. 10.1038/bjc.2014.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Shi X.; Zhao H.; Yang M.; Wang C.; Liao M.; Zhao J. Nicotine Induces Cell Survival and Chemoresistance by Stimulating Mcl-1 Phosphorylation and Its Interaction with Bak in Lung Cancer. J. Cell Physiol 2019, 234 (9), 15934. 10.1002/jcp.28251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. C.; Tsai K. Y.; Su Y. F.; Chien C. Y.; Chen Y. C.; Wu Y. C.; Liu S. Y.; Shieh Y. S. A7-Nicotine Acetylcholine Receptor Mediated Nicotine Induced Cell Survival and Cisplatin Resistance in Oral Cancer. Arch Oral Biol. 2020, 111, 104653. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu C. C.; Huang C. Y.; Cheng W. L.; Hung C. S.; Uyanga B.; Wei P. L.; Chang Y. J. The A7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Mediates the Sensitivity of Gastric Cancer Cells to Taxanes. Tumor Biology 2016, 37 (4), 4421. 10.1007/s13277-015-4260-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour M. A.; Kheradmand F.; Rasmi Y.; Baradaran B. Alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Expression in Sorafenib-Resistant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39 (11), 165. 10.1007/s12032-022-01745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper H. H. Progression and Metastasis of Lung Cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016, 35 (1), 75. 10.1007/s10555-016-9618-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrinsky N. L.; Klug M. G.; Hokanson P. J.; Sjolander D. E.; Burd L. Impact of Smoking on Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21 (5), 907. 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Z.; Cheng X.; Li X. C.; Liu Y. Q.; Wang X. Q.; Shi X.; Wang Z. Y.; Guo Y. Q.; Wen Z. S.; Huang Y. C.; Zhou G. B. Tobacco Smoke Induces Production of Chemokine CCL20 to Promote Lung Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 363 (1), 60. 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood M. Q.; Ward C.; Muller H. K.; Sohal S. S.; Walters E. H. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): A Mutual Association with Airway Disease. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34 (3), 45. 10.1007/s12032-017-0900-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal C. M.; Bora-Singhal N.; Kumar D. M.; Chellappan S. P. Regulation of Sox2 and Stemness by Nicotine and Electronic-Cigarettes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17 (1), 149. 10.1186/s12943-018-0901-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhummaphan N.; Petpiroon N.; Prakhongcheep O.; Sritularak B.; Chanvorachote P. Lusianthridin Targeting of Lung Cancer Stem Cells via Src-STAT3 Suppression. Phytomedicine 2019, 62, 152932 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien C. Y.; Chen Y. C.; Hsu C. C.; Chou Y. T.; Shiah S. G.; Liu S. Y.; Hsieh A. C. T.; Yen C. Y.; Lee C. H.; Shieh Y. S. YAP-Dependent Bip Induction Is Involved in Nicotine- Mediated Oral Cancer Malignancy. Cells 2021, 10 (8), 2080. 10.3390/cells10082080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. D.; Le T. M.; Haggstrom D. E.; Gentzler R. D. Angiogenesis Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2015, 4, 515–525. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. C.; Lau J. K.; Dom A. M.; Witte T. R.; Luo H.; Crabtree C. M.; Shah Y. H.; Shiflett B. S.; Marcelo A. J.; Proper N. A.; Hardman W. E.; Egleton R. D.; Chen Y. C.; Mangiarua E. I.; Dasgupta P. MG624, an A7-NAChR Antagonist, Inhibits Angiogenesis via the Egr-1/FGF2 Pathway. Angiogenesis 2012, 15 (1), 99–114. 10.1007/s10456-011-9246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S. B.; Sulzenbacher G.; Huxford T.; Marchot P.; Taylor P.; Bourne Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP Complexes with Nicotinic Agonists and Antagonists Reveal Distinctive Binding Interfaces and Conformations. EMBO J. 2005, 24 (20), 3635–3646. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; He X.; Wang X.; Yu B.; Zhao S.; Jiao P.; Jin H.; Liu Z.; Wang K.; Zhang L.; Zhang L. Design, Synthesis and Biological Activities of Piperidine-Spirooxadiazole Derivatives as A7 Nicotinic Receptor Antagonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112774 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W.; Ding F. Biomolecular Recognition of Antagonists by A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor: Antagonistic Mechanism and Structure-Activity Relationships Studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 76, 119–132. 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunrungvichian K.; Fokin V. V.; Vajragupta O.; Taylor P. Selectivity Optimization of Substituted 1,2,3-Triazoles as A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6 (8), 1317–1330. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J. J.; García-Colunga J.; Pérez E. G.; Fierro A. Methylpiperidinium Iodides as Novel Antagonists for A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 744. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunrungvichian K.; Chongruchiroj S.; Sarasamkan J.; Schüürmann G.; Brust P.; Vajragupta O. In Silico Finding of Key Interaction Mediated A3β4 and A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Ligand Selectivity of Quinuclidine-Triazole Chemotype. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (17), 6189. 10.3390/ijms21176189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne S.; Čemažar M.; Frangež R.; Juntes P.; Kranjc S.; Grandič M.; Savarin M.; Turk T. APS8 Delays Tumor Growth in Mice by Inducing Apoptosis of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Expressing High Number of A7 Nicotinic Receptors. Mar Drugs 2018, 16 (10), 367. 10.3390/md16100367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta P.; Rastogi S.; Pillai S.; Ordonez-Ercan D.; Morris M.; Haura E.; Chellappan S. Nicotine Induces Cell Proliferation by Beta-Arrestin-Mediated Activation of Src and Rb-Raf-1 Pathways. J. Clin Invest 2006, 116 (8), 2208–2217. 10.1172/JCI28164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qasem A. M. A.; Rowan M. G.; Sanders V. R.; Millar N. S.; Blagbrough I. S. Synthesis and Antagonist Activity of Methyllycaconitine Analogues on Human A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. ACS bio & med chem Au 2023, 3 (2), 147–157. 10.1021/acsbiomedchemau.2c00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama R.; Aoshiba K.; Furukawa K.; Saito M.; Kataba H.; Nakamura H.; Ikeda N. Nicotine Enhances Hepatocyte Growth Factor-Mediated Lung Cancer Cell Migration by Activating the A7 Nicotine Acetylcholine Receptor and Phosphoinositide Kinase-3-Dependent Pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016, 11 (1), 673–677. 10.3892/ol.2015.3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher R.; Qudah T.; Balle T.; Chebib M.; McLeod M. D. Novel Methyllycaconitine Analogues Selective for the A4β2 over A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 51, 116516 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuong M. A.; Mahardika G. N. Targeted Sequencing of Venom Genes from Cone Snail Genomes Improves Understanding of Conotoxin Molecular Evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35 (5), 1210–1224. 10.1093/molbev/msy034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. W.; Marquart L. A.; Phillips P. D.; McDougal O. M. Mutagenesis of α-Conotoxins for Enhancing Activity and Selectivity for Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11 (2), 113. 10.3390/toxins11020113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekbossynova A.; Zharylgap A.; Filchakova O. Venom-Derived Neurotoxins Targeting Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Molecules 2021, 26 (11), 3373. 10.3390/molecules26113373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Li Y.; Yang M.; Zhou M. Synthesis and Characterization of AM-Conotoxin SIIID, a Reversible Human A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonist. Toxicon 2022, 210, 141–147. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2022.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei D.; Zhao L.; Chen B.; Zhang X.; Wang X.; Yu Z.; Ni X.; Zhang Q. α-Conotoxin ImI-Modified Polymeric Micelles as Potential Nanocarriers for Targeted Docetaxel Delivery to A7-NAChR Overexpressed Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Drug Deliv 2018, 25 (1), 493–503. 10.1080/10717544.2018.1436097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamida D.; Poulas K.; Avramopoulou V.; Fostieri E.; Lagoumintzis G.; Lazaridis K.; Sideri A.; Zouridakis M.; Tzartos S. J. Muscle and Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Structure, Function and Pathogenicity. FEBS J. 2007, 274 (15), 3799–3845. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebbe E. K. M.; Peigneur S.; Maiti M.; Mille B. G.; Devi P.; Ravichandran S.; Lescrinier E.; Waelkens E.; D’Souza L.; Herdewijn P.; Tytgat J. Discovery of a New Subclass of α-Conotoxins in the Venom of Conus Australis. Toxicon 2014, 91, 145–154. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J.; Xu L.; Owonikoko T. K.; Sun S.-Y.; Khuri F. R.; Curran W. J.; Deng X. NNK Promotes Migration and Invasion of Lung Cancer Cells through Activation of C-Src/PKCι/FAK Loop. Cancer Lett. 2012, 318 (1), 106–113. 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindel E. R. Cholinergic Targets in Lung Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des 2016, 22 (14), 2152–2159. 10.2174/1381612822666160127114237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani-Boroujerdi S.; Boyd R. T.; Dávila-García M. I.; Nandi J. S.; Mishra N. C.; Singh S. P.; Pena-Philippides J. C.; Langley R.; Sopori M. L. T Cells Express Alpha7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunits That Require a Functional TCR and Leukocyte-Specific Protein Tyrosine Kinase for Nicotine-Induced Ca2+ Response. J. Immunol 2007, 179 (5), 2889–2898. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. R.; Kabbani N. Alpha 7 Nicotinic Receptor Coupling to Heterotrimeric G Proteins Modulates RhoA Activation, Cytoskeletal Motility, and Structural Growth. J. Neurochem 2016, 138 (4), 532–545. 10.1111/jnc.13660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov M. L.; Shulepko M. A.; Shlepova O. V.; Kulbatskii D. S.; Chulina I. A.; Paramonov A. S.; Baidakova L. K.; Azev V. N.; Koshelev S. G.; Kirpichnikov M. P.; Shenkarev Z. O.; Lyukmanova E. N. SLURP-1 Controls Growth and Migration of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells, Forming a Complex With A7-NAChR and PDGFR/EGFR Heterodimer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 739391 10.3389/fcell.2021.739391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriwaki Y.; Kubo N.; Watanabe M.; Asano S.; Shinoda T.; Sugino T.; Ichikawa D.; Tsuji S.; Kato F.; Misawa H. Endogenous Neurotoxin-like Protein Ly6H Inhibits Alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Currents at the Plasma Membrane. Sci. Rep 2020, 10 (1), 11996. 10.1038/s41598-020-68947-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklow B.; Kornhauser R.; Hains P. G.; Loiacono R.; Escoubas P.; Graudins A.; Nicholson G. M. α-Elapitoxin-Aa2a, a Long-Chain Snake α-Neurotoxin with Potent Actions on Muscle (A1)(2)Bγδ Nicotinic Receptors, Lacks the Classical High Affinity for Neuronal A7 Nicotinic Receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 81 (2), 314–325. 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nys M.; Zarkadas E.; Brams M.; Mehregan A.; Kambara K.; Kool J.; Casewell N. R.; Bertrand D.; Baenziger J. E.; Nury H.; Ulens C. The Molecular Mechanism of Snake Short-Chain α-Neurotoxin Binding to Muscle-Type Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 4543. 10.1038/s41467-022-32174-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alama A.; Bruzzo C.; Cavalieri Z.; Forlani A.; Utkin Y.; Casciano I.; Romani M. Inhibition of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors by Cobra Venom α-Neurotoxins: Is There a Perspective in Lung Cancer Treatment. PLoS One 2011, 6 (6), e20695 10.1371/journal.pone.0020695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozio A.; Paleari L.; Catassi A.; Servent D.; Cilli M.; Piccardi F.; Paganuzzi M.; Cesario A.; Granone P.; Mourier G.; Russo P. Natural Agents Targeting the Alpha7-Nicotinic-Receptor in NSCLC: A Promising Prospective in Anti-Cancer Drug Development. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122 (8), 1911–1915. 10.1002/ijc.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catassi A.; Paleari L.; Servent D.; Sessa F.; Dominioni L.; Ognio E.; Cilli M.; Vacca P.; Mingari M.; Gaudino G.; Bertino P.; Paolucci M.; Calcaterra A.; Cesario A.; Granone P.; Costa R.; Ciarlo M.; Alama A.; Russo P. Targeting Alpha7-Nicotinic Receptor for the Treatment of Pleural Mesothelioma. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44 (15), 2296–2311. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulepko M. A.; Bychkov M. L.; Shenkarev Z. O.; Kulbatskii D. S.; Makhonin A. M.; Paramonov A. S.; Chugunov A. O.; Kirpichnikov M. P.; Lyukmanova E. N. Biochemical Basis of Skin Disease Mal de Meleda: SLURP-1 Mutants Differently Affect Keratinocyte Proliferation and Apoptosis. J. Invest Dermatol 2021, 141 (9), 2229–2237. 10.1016/j.jid.2021.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulepko M. A.; Bychkov M. L.; Shlepova O. V.; Shenkarev Z. O.; Kirpichnikov M. P.; Lyukmanova E. N. Human Secreted Protein SLURP-1 Abolishes Nicotine-Induced Proliferation, PTEN down-Regulation and A7-NAChR Expression up-Regulation in Lung Cancer Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol 2020, 82, 106303 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X. W.; Song P. F.; Spindel E. R. Role of Lynx1 and Related Ly6 Proteins as Modulators of Cholinergic Signaling in Normal and Neoplastic Bronchial Epithelium. Int. Immunopharmacol 2015, 29 (1), 93–98. 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Su C.; Hang M.; Huang H.; Zhao Y.; Shao X.; Bu X. Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus RL-RVG Enhances the Apoptosis and Inhibits the Migration of A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells via Regulating Alpha 7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Vitro. Virol J. 2017, 14 (1), 190. 10.1186/s12985-017-0852-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison M.; Gao F.; Wang H.-L.; Sine S. M.; McIntosh J. M.; Olivera B. M. Alpha-Conotoxins ImI and ImII Target Distinct Regions of the Human Alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor and Distinguish Human Nicotinic Receptor Subtypes. Biochemistry 2004, 43 (51), 16019–16026. 10.1021/bi048918g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandna R.; Tae H.-S.; Seymour V. A. L.; Chathrath S.; Adams D. J.; Kini R. M. Drysdalin, an Antagonist of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Highlights the Importance of Functional Rather than Structural Conservation of Amino Acid Residues. FASEB Bioadv 2019, 1 (2), 115–131. 10.1096/fba.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipov A. V.; Rucktooa P.; Kasheverov I. E.; Filkin S. Y.; Starkov V. G.; Andreeva T. V.; Sixma T. K.; Bertrand D.; Utkin Y. N.; Tsetlin V. I. Dimeric α-Cobratoxin X-Ray Structure: Localization of Intermolecular Disulfides and Possible Mode of Binding to Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287 (9), 6725–6734. 10.1074/jbc.M111.322313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipov A. V.; Kasheverov I. E.; Makarova Y. V.; Starkov V. G.; Vorontsova O. V.; Ziganshin R. K.; Andreeva T. V.; Serebryakova M. V.; Benoit A.; Hogg R. C.; Bertrand D.; Tsetlin V. I.; Utkin Y. N. Naturally Occurring Disulfide-Bound Dimers of Three-Fingered Toxins: A Paradigm for Biological Activity Diversification. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (21), 14571–14580. 10.1074/jbc.M802085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durek T.; Shelukhina I. V.; Tae H.-S.; Thongyoo P.; Spirova E. N.; Kudryavtsev D. S.; Kasheverov I. E.; Faure G.; Corringer P.-J.; Craik D. J.; Adams D. J.; Tsetlin V. I. Interaction of Synthetic Human SLURP-1 with the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Sci. Rep 2017, 7 (1), 16606. 10.1038/s41598-017-16809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyukmanova E. N.; Shulepko M. A.; Kudryavtsev D.; Bychkov M. L.; Kulbatskii D. S.; Kasheverov I. E.; Astapova M. V.; Feofanov A. V.; Thomsen M. S.; Mikkelsen J. D.; Shenkarev Z. O.; Tsetlin V. I.; Dolgikh D. A.; Kirpichnikov M. P. Human Secreted Ly-6/UPAR Related Protein-1 (SLURP-1) Is a Selective Allosteric Antagonist of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. PLoS One 2016, 11 (2), e0149733 10.1371/journal.pone.0149733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov M.; Shenkarev Z.; Shulepko M.; Shlepova O.; Kirpichnikov M.; Lyukmanova E. Water-Soluble Variant of Human Lynx1 Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Lung Cancer Cells via Modulation of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. PLoS One 2019, 14 (5), e0217339 10.1371/journal.pone.0217339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavo F.; Pallavicini M.; Pucci S.; Appiani R.; Giraudo A.; Oh H.; Kneisley D. L.; Eaton B.; Lucero L.; Gotti C.; Clementi F.; Whiteaker P.; Bolchi C. Subnanomolar Affinity and Selective Antagonism at A7 Nicotinic Receptor by Combined Modifications of 2-Triethylammonium Ethyl Ether of 4-Stilbenol (MG624. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66 (1), 306–332. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger-Coast M. G.; Zhang M.; Bugay V.; Gutierrez R. A.; Gregory S. R.; Yu W.; Brenner R. Dequalinium Chloride Is an Antagonists of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 925, 175000 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissonnet Y.; Araoz R.; Sousa R.; Percevault L.; Brument S.; Deniaud D.; Servent D.; Le Questel J.-Y.; Lebreton J.; Gouin S. G. Di- and Heptavalent Nicotinic Analogues to Interfere with A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27 (5), 700–707. 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadek B.; Ashoor A.; Al Mansouri A.; Lorke D. E.; Nurulain S. M.; Petroianu G.; Wainwright M.; Oz M. N3,N7-Diaminophenothiazinium Derivatives as Antagonists of A7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66 (3), 213–218. 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwassil O. I.; Khatri S.; Schulte M. K.; Aripaka S. S.; Mikkelsen J. D.; Dukat M. N1H- and N1-Substituted Phenylguanidines as A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine (NACh) Receptor Antagonists: Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12 (12), 2194–2201. 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesolowska A.; Young S.; Dukat M. MD-354 Potentiates the Antinociceptive Effect of Clonidine in the Mouse Tail-Flick but Not Hot-Plate Assay. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 495 (2–3), 129–136. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.; Saito E.; Ekins S.; McMurtray A. Extracellular Binding of Indinavir to Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 and the Alpha-7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor: Implications for Use in Cancer Treatment. Heliyon 2019, 5 (9), e02526 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier S. C.; Lapinsky D. J.; Free R. B.; McKay D. B. Ring E Analogs of Methyllycaconitine (MLA) as Novel Nicotinic Antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9 (15), 2263–2266. 10.1016/S0960-894X(99)00378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S. S.; Tang Q.; Zheng F.; Zhao S.; Wu J. GW1929 Inhibits A7 NAChR Expression through PPARγ-Independent Activation of P38 MAPK and Inactivation of PI3-K/MTOR: The Role of Egr-1. Cell Signal 2014, 26 (4), 730–739. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi Y.-K.; Li J.; Yi L.; Zhu R.-L.; Luo J.-F.; Shi Q.-P.; Bai S.-S.; Li Y.-W.; Du Q.; Cai J.-Z.; Liu L.; Wang P.-X.; Zhou H.; Dong Y. Sinomenine Inhibits Macrophage M1 Polarization by Downregulating A7nAChR via a Feedback Pathway of A7nAChR/ERK/Egr-1. Phytomedicine 2022, 100, 154050 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi L.; Palma E.; Eusebi F.; Moretti M.; Balestra B.; Clementi F.; Gotti C. Selective Effects of a 4-Oxystilbene Derivative on Wild and Mutant Neuronal Chick Alpha7 Nicotinic Receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 126 (1), 285–295. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K.-H.; Hung J.-H.; Liao Y.-C.; Tsai S.-T.; Wu M.-J.; Chen P.-S. Sinomenine Inhibits Migration and Invasion of Human Lung Cancer Cell through Downregulating Expression of MiR-21 and MMPs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (9), 3080. 10.3390/ijms21093080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.; Gao Y.; Hou W.; Liu R.; Qi X.; Xu X.; Li J.; Bao Y.; Zheng H.; Hua B. Sinomenine Inhibits A549 Human Lung Cancer Cell Invasion by Mediating the STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016, 12 (2), 1380–1386. 10.3892/ol.2016.4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C.; Carbonnelle E.; Moretti M.; Zwart R.; Clementi F. Drugs Selective for Nicotinic Receptor Subtypes: A Real Possibility or a Dream?. Behavioural brain research 2000, 113 (1–2), 183–192. 10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosi P.; Becchetti A. Targeting Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors in Cancer: New Ligands and Potential Side-Effects. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov 2012, 8 (1), 38–52. 10.2174/15748928130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]