Abstract

Background

Persistent feelings of fatigue (or subjective fatigue), which may be experienced in the absence of physiological factors, affect many people with peripheral neuropathy. A variety of interventions for subjective fatigue are available, but little is known about their efficacy or the likelihood of any adverse effects for people with peripheral neuropathy.

Objectives

To assess the effects of drugs and physical, psychological or behavioural interventions for fatigue in adults or children with peripheral neuropathy.

Search methods

On 5 November 2013, we searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, LILACS and AMED. We also searched reference lists of all studies identified for inclusion and relevant reviews, and contacted the authors of included studies and known experts in the field to identify additional published or unpublished data. We also searched trials registries for ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

We considered for inclusion randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing any form of intervention for fatigue management in adults with peripheral neuropathy with placebo, no intervention or an alternative form of intervention for fatigue. Interventions considered included drugs, pacing and grading of physical activity, general or specific exercise, compensatory strategies such as orthotics, relaxation, counselling, cognitive and educational strategies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias and extracted study data. We contacted study authors for additional information. We collected information on adverse events from the included trials.

Main results

The review includes three trials, which were all at low risk of bias, involving 530 people with peripheral neuropathy. The effects of amantadine from one randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial comparing amantadine with placebo for the treatment of fatigue in 80 people with Guillain‐Barré syndrome (GBS) were uncertain for the proportion of people achieving a favourable outcome six weeks post‐intervention (odds ratio (OR) 0.56 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.22 to 1.35, N = 74, P = 0.16). We assessed the quality of this evidence as low. Two parallel‐group randomised double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials comparing the effects of two doses of ascorbic acid with placebo for reducing fatigue in adults with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A) showed that the effects of ascorbic acid at either dose are probably small (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.12 (95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.08, n = 404, P = 0.25)) for change in fatigue after 12 to 24 months (moderate quality evidence). Neither ascorbic acid study measured fatigue at four to 12 weeks, which was our primary outcome measure. No serious adverse events were reported with amantadine. Serious adverse events were reported in the trials of ascorbic acid. However,risk of serious adverse events was similar with ascorbic acid and placebo.

Authors' conclusions

One small imprecise study in people with GBS showed uncertain effects of amantadine on fatigue. In two studies in people with CMT1A there is moderate‐quality evidence that ascorbic acid has little meaningful benefit on fatigue. Information about adverse effects was limited, although both treatments appear to be well tolerated and safe in these conditions.

There was no evidence available from RCTs to evaluate the effect of other drugs or other interventions for fatigue in either GBS, CMT1A or other causes of peripheral neuropathy. The cost effectiveness of different interventions should also be considered in future randomised clinical trials.

Keywords: Adult, Child, Humans, Amantadine, Amantadine/adverse effects, Amantadine/therapeutic use, Ascorbic Acid, Ascorbic Acid/adverse effects, Ascorbic Acid/therapeutic use, Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth Disease, Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth Disease/complications, Fatigue, Fatigue/etiology, Fatigue/therapy, Guillain‐Barre Syndrome, Guillain‐Barre Syndrome/complications, Peripheral Nervous System Diseases, Peripheral Nervous System Diseases/complications, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Treatments for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy

Review question

To assess the effects of treatments for fatigue in people with peripheral neuropathy.

Background

Peripheral neuropathy is damage to the nerves outside the brain and spinal cord. Many people with peripheral neuropathy have feelings of severe tiredness (fatigue) that are not necessarily related to physical problems such as muscle weakness. Evidence in other long‐term illnesses where fatigue is a problem suggests that medicines and other forms of treatment may help. The aim of this review was to assess the effect of drugs and other treatments, such as general or specific exercise, orthotics (devices such as braces), relaxation, counselling and cognitive, behavioural and educational strategies on feelings of fatigue in people with peripheral neuropathy.

Study characteristics

From a wide search, we identified three RCTs that met our selection criteria. The trials involved a total of 530 adults with peripheral neuropathy. Treatments were ascorbic acid (vitamin C) in people with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease in two trials, and amantadine in Guillain‐Barré syndrome in the third. Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease is an inherited nerve disease and Guillain‐Barré syndrome is a condition where there is inflammation of the peripheral nerves. We chose measures of fatigue at four to 12 weeks as our preferred measure of the effects of treatment. The amantadine trial but not the ascorbic acid trials provided data at this time point; the ascorbic acid trials provided data more than 12 months after the start of the intervention.

Key results and quality of the evidence

There was insufficient evidence to determine the effects of amantadine when compared with an inactive treatment (placebo) for fatigue. and there were no major unwanted effects. We found evidence that ascorbic acid probably has little meaningful benefit for fatigue. No major unwanted effects were identified, but the trials were small. We assessed the quality of this evidence as moderate because the results were imprecise, which means they do not rule out the possibility that the drugs could have an effect. We found no evidence from RCTs on other medicines or treatments for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy.

There is insufficient evidence to determine the effect of amantadine for fatigue in GBS and ascorbic acid for fatigue in CMT1A. More high‐quality studies are needed to provide evidence on which to base management of feelings of fatigue in peripheral neuropathy. The cost effectiveness of different interventions should also be considered in future RCTs.

The evidence in this review is current to November 2013.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Amantadine versus placebo for fatigue in Guillain‐Barré syndrome.

| Amantadine versus placebo for fatigue in Guillain‐Barré syndrome | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with fatigue in Guillain‐Barré syndrome Settings: Intervention: amantadine versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Amantadine | |||||

| Reduction in fatigue of at least 1‐point on the Fatigue Severity Scale between 4 to 12 weeks after commencement of intervention Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) from 1 to 7 (higher score is worse) Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 257 per 1000 | 162 per 1000 (71 to 318) | OR 0.56 (0.22 to 1.35) | 74 (1 cross‐over study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| Change in fatigue 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention (not measured) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Change in activity limitation 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention (not measured) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Change in participation 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention using the Rotterdam Handicap Scale. Scale from: 0 to 36. Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean change in participation 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention using the control group was 0.34 points | The mean change in participation 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention using the intervention group was 0.31 higher (0.09 lower to 0.72 higher) | 74 (1 cross‐over study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ | |

| Health related quality of life after 12 or more weeks or more after commencement of intervention (not reported) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | EHQ and SF‐36 measured but data not fully reported |

| Serious adverse events Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 80 (1 cross‐over study) | See comment | 0 participants had serious adverse events in this study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Evidence downgraded two levels due to imprecision (small sample size and wide CI that crosses the line of no effect).

Summary of findings 2. Ascorbic acid versus placebo for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy.

| Ascorbic acid versus placebo for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with fatigue in peripheral neuropathy Settings: Intervention: ascorbic acid versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Ascorbic acid | |||||

| Reduction in fatigue of at least 1 point on the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) between 4 to 12 weeks after commencement of intervention (not measured) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Change in fatigue 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of fatigue Follow‐up: mean 12‐24 months | ‐ | The mean change in fatigue 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention in the intervention groups was 0.12 standard deviations lower (0.32 lower to 0.08 higher) | ‐ | 404 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

| Change in activity limitation (ODSS/ONLS) 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention Overall Neuropathy Limitations Scale or Overall Disability Sum Score. Scale from: 0 to 12. Follow‐up: 12‐24 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 406 (2 studies) | ‐ | Data available were not suitable for meta‐analysis |

| Change in 10 metre timed walk 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention Time taken to walk 10 metres in seconds Follow‐up: 12‐24 months | The mean changes in 10 metre timed walk 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention in the control groups werea decrease of 0.40 seconds and an increase of 0.76 seconds2 | The mean change in 10 metre timed walk 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention in the intervention groups was a decrease of 0.39 seconds (1.04 faster to 0.26 slower) | 406 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ | |

| Change in speed of completion of 9‐hole peg test (in seconds) 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention Time (in seconds) taken to complete 9‐hole peg test Follow‐up: mean 24 months | The mean change in speed of completion of the 9‐hole peg test was an increase of 0.85 seconds in the control group | The mean change in speed of completion of the 9‐hole peg test was a decrease of 0.74 seconds (1.60 faster to 0.12 slower) |

Not estimable | 224 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

|

Health‐related quality of life 12 or more weeks after commencement of the intervention Change in SF‐36 physical function score SF‐36 Physical Functioning Scale and Physical Component Score Follow‐up: 12‐24 months |

‐ | The mean health‐related quality of life 12 or more weeks after commencement of the intervention (change in SF‐36 physical function score) in the intervention groups was 0.08 standard deviations higher (0.12 lower to 0.28 higher) | ‐ | 400 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

| Change in participation 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention (not measured) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

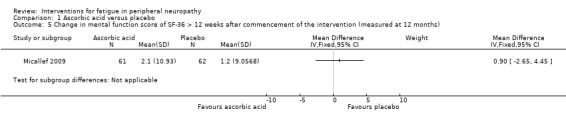

| Health‐related quality of life 12 or more weeks after commencement of the intervention Change in mental function score of SF‐36 SF‐36 Mental Component Score Follow‐up: mean 12 months | The mean change in health‐related quality of life 12 or more weeks after commencement of the intervention (change in mental function score of SF‐36) in the control group was 1.2 points | The mean health‐related quality of life 12 or more weeks after commencement of the intervention (change in mental function score of SF‐36) in the intervention groups was 0.9 higher (2.65 lower to 4.45 higher) | ‐ | 123 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

| Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 12 months | 108 per 1000 | 76 per 1000 (42 to 137) | RR 0.70 (0.39 to 1.27) | 450 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ moderate1 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Only one or two studies included. 2 Assumed control group risks are the control group values in the two trials.

Background

Description of the condition

Peripheral neuropathies collectively affect about 2.4% of the population and may be either genetic or acquired, and either acute or chronic in nature (Martyn 1998). The pathological process affects peripheral nerves, resulting in neurological damage to either the axon (ie, degeneration of the central nerve fibre), the myelin (ie, demyelination or destruction of the insulating sheath of the nerve), or a combination of both. Recovery may be by remyelination, through which improvements in function can be rapid, and in some people there is almost complete recovery. However, regeneration of damaged axons usually takes many months or years and recovery, if present, may be incomplete (Tamura 2007).

Common symptoms of peripheral neuropathy include numbness, diminished or altered sensation (pins and needles), muscle weakness, and autonomic dysfunction. People may also experience fatigue, pain, psychological dysfunction and poor social adjustment (Lennon 1993; Pfeiffer 2001). Even when neurological function improves, residual symptoms often persist and fatigue is frequently an ongoing problem (Merkies 1999).

The experience of fatigue (or subjective fatigue) has been described as a "an overwhelming sense of tiredness, lack of energy and feeling of exhaustion" that is "not relieved by rest" and is a common sequel of chronic conditions (Bleijenberg 2003; Karlsen 1999; Krupp 2003). Physiological fatigue, or "the loss of voluntary force‐producing capacity during exercise" (Bigland‐Ritchie 1978) can contribute to subjective fatigue, but people can experience subjective fatigue in the absence of physiological factors and physiological fatigue does not necessarily result in subjective fatigue. Physical factors such as residual muscle weakness mean that people with peripheral neuropathy have to work harder during everyday activities than healthy individuals, which will feel more of an effort. Axonal degeneration prevents nerve impulses from being conducted along the peripheral nerve and demyelination can lead to conduction block that can be exacerbated by muscle activity (Cappelen‐Smith 2000), leading to fatigue (Kaji 2000). Although there is no direct problem with the muscles themselves, it has been shown that people with peripheral neuropathy may be unable to voluntarily activate their muscles fully, possibly because of dysfunction within the central nervous system (Garssen 2007; Schillings 2003). This form of physiological fatigue is known as central fatigue and could possibly be due to reduced drive from nerve cells in the brain (cortical neurons) or to the effect of alterations in the number of surviving peripheral nerve axons and an increase in the number of muscle fibres they innervate (Martinez‐Figuerora 1977; Sanders 1996). In addition, psychological factors such as lack of motivation or low mood can also affect voluntary activation of muscles (Gandevia 2001; Kent‐Braun 1993). Fear of precipitating fatigue may also contribute and lead to an avoidance of physical activity and physical deconditioning, thus further exacerbating fatigue (Moss‐Morris 2005). Environmental factors may also precipitate fatigue, since many people with peripheral neuropathies have to utilise compensatory strategies such as orthoses or walking aids as a result of deformities or sensory deficits. Therefore, the experience of fatigue may be clearly related to known underlying factors or, more commonly, be only partly explained by these. Finally, measurement of the level of fatigue is difficult both because the subjective experience of fatigue varies between individuals and because measures of different types of fatigue are numerous.

Description of the intervention

The evidence about the efficacy of interventions for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy and other chronic conditions is limited and unclear. Interventions aim to address physical, environmental and psychological factors contributing to fatigue, and include drugs, pacing and grading of physical activity, general or specific exercise, orthotics, relaxation, counselling, cognitive behavioural strategies and others.

How the intervention might work

The presumed mode of action of drug interventions such as amantadine for generalised fatigue is unknown (Pucci 2009); one randomised controlled trial (RCT) showed no effect in inflammatory peripheral neuropathy (Garssen 2006). It is likely that factors contributing to subjective fatigue in individuals with peripheral neuropathy must be clearly understood in order to target interventions effectively. For example, where fatigue is due to weakness, strengthening exercise may be beneficial, but where altered mood or well‐being is a factor then drug, cognitive or behavioural interventions may be more relevant. It is likely that multidimensional interventions that address individuals' self perception and health beliefs combined with strategies to increase levels of physical activity or participation in regular exercise or both may also be helpful.

Why it is important to do this review

Fatigue is a frequent and often severe problem that affects everyday activities and quality of life for people with peripheral neuropathy. Although there have been some RCTs of drug and non‐drug interventions for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy, we know of no systematic review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of drugs and physical, psychological or behavioural interventions for fatigue in adults or children with peripheral neuropathy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs of any drug or non‐drug intervention to treat fatigue associated with peripheral neuropathy, compared with placebo, no treatment or other drug or non‐drug interventions for fatigue. Quasi‐RCTs are those in which randomisation was intended but they use methodology that may be biased, such as alternation, or use of case record numbers or date of birth.

Types of participants

We considered for inclusion in the review all trials in which participants (adults or children) had fatigue associated with a diagnosis of peripheral polyneuropathy, including sensory, motor and combined sensory and motor neuropathies. We did not consider trials including mostly people with focal disease such as local entrapment neuropathies with pain as the primary presenting feature (for example, cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, brachial plexus neuritis, etc), and poliomyelitis. We accepted the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy offered by the study authors, provided that it stipulated the presence of clinical impairment characteristic of peripheral neuropathy. We did not include diagnoses dependent on symptoms suggestive of neuropathy alone or neurophysiological abnormalities in the absence of clinical signs.

Types of interventions

We considered trials including any form of intervention for fatigue management, such as drugs, pacing and grading of physical activity, general or specific exercise, compensatory strategies such as orthotics, relaxation, counselling, cognitive and educational strategies and others, compared with either placebo, no intervention or an alternative form of intervention for fatigue.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was fatigue severity and symptoms as measured by any validated scale evaluated at least four weeks and less than 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention. Where studies used more than one scale, we used the preferred ranking of commonly‐used scales shown below to identify the scale to be used in the primary outcome analysis. Instruments that we considered appropriate included: Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) (Krupp 1989), Chalder Fatigue Scale (Chalder 1993), Fatigue Impact Scale or daily‐FIS (D‐FIS) (Fisk 1994; Fisk 2002), Visual Analogue Scale of Fatigue (VAS‐F) (Lee 1991), and Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS) (Piper 1998).

Secondary outcomes

1. Fatigue after 12 or more weeks.

2. Activity limitations after 12 or more weeks.

3. Participation restrictions after 12 or more weeks.

4. Health‐related quality of life after 12 or more weeks.

5. Adverse events: any adverse events, adverse events which lead to discontinuation of treatment and serious adverse events, which are those which are fatal, life‐threatening, or require prolonged hospitalisation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

On 5 November 2013, we searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 10), MEDLINE (January 1966 to October 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to October 2013), LILACS (January 1982 to October 2013), CINAHL Plus (January 1937 to October 2013) and AMED (January 1985 to October 2013). The detailed search strategies are in the appendices: Appendix 1 (MEDLINE), Appendix 2 (EMBASE), Appendix 3 (CINAHL Plus), Appendix 4 (CENTRAL), Appendix 5 (AMED), Appendix 6 (LILACS) and Appendix 7 (the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register).

On 12 June 2014 we searched the Current Controlled Trials register (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/), using the search terms 'fatigue' and 'peripheral neuropathy'.

Searching other resources

We reviewed the bibliographies of the randomised trials identified, contacted the trial authors and known experts in the field, and approached pharmaceutical companies to identify additional published or unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CMW, RCS) independently examined the titles and abstracts identified by the search. There were no language restrictions. We obtained English language translations where appropriate. We retrieved all trials that were relevant and reviewed full‐text publications. We examined retrieved publications against the selection criteria and we resolved any disagreement by consensus.We did not have to resort to arbitration by a third author (MPG). If trials had had a heterogenous sample of disorders, we would have only included them if data from participants with peripheral neuropathy could be isolated or if at least 75% of the participants had peripheral neuropathy.

Data extraction and management

For each retrieved publication, two review authors (CW and RCS) independently extracted the relevant data using standardised forms. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We gathered data on:

eligibility criteria;

interventions;

details of participants;

assignment to groups;

outcome measures;

time at which outcomes are measured;

funding;

declarations of interest;

sample size; and

statistical analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two out of three review authors (CW, RS and MG) independently assessed all included studies for risk of bias. We graded the items according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a) and presented our assessments in a 'Risk of bias' table. We assessed trials for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel and outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias. We then made a judgement on each of these criteria relating to the risk of bias, of 'low risk of bias', 'high risk of bias' or 'unclear risk of bias'.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

For studies using the same outcome measures, we summarised continuous data using mean differences (MDs), sometimes called 'weighted mean differences', with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). When different studies measured the same outcome in different ways we analysed results using standardised mean differences (SMDs) with a 95% CI.

Dichotomous data

For studies using similar outcomes with dichotomous data we calculated a pooled estimate of the risk ratio (RR), with a 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

Where there were multiple intervention groups within a trial, we made pairwise comparisons of similar interventions or active components versus no treatment, placebo, or another intervention. We planned to analyse cross‐over trials with continuous outcome measures using generalised inverse variance analysis (GIV) (DerSimonian 1986), where the estimated difference in the mean treatment effects and their standard errors were available for pooling with equivalent results from parallel‐group studies. If this information had not been available then we would have pooled data from the first phase only, where possible, with parallel design studies. For cross‐over studies with dichotomous outcomes we would have pooled results using odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals from paired analyses where available (Elbourne 2002). Only one cross‐over trial was included for any comparison, so no decisions about pooling data were necessary. We would have reported trials with unique designs or outcomes without a meta‐analysis. We excluded studies that were not RCTs from the analyses but we comment on them in the Discussion.

Dealing with missing data

For all outcomes, where continuous data were presented as mean change with 95% CIs, the standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for input into analyses and forest plots assuming a normal distribution due to a moderate sample size, using the equation SD = SQRT of number of participants X (upper limit of CI to lower limit of CI) / 3.92. as recommended in Section 7.7.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). Where overall disability sum score (ODSS) data were presented as median and interquartile ranges, we did not input any data for analysis. Where participant dropout led to missing data we contacted trial authors if an intention‐to‐treat analysis had not been performed. We also contacted authors where there were missing data for review outcomes, and additional data were provided for the secondary outcome of participation in one study (Garssen 2006).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We undertook meta‐analysis when studies investigated similar interventions, used similar outcome measures and included groups of participants who were clinically homogeneous. Where studies were heterogeneous for some outcomes we undertook a narrative review.

If studies were similar in intervention, outcome measurement and participants, we assessed possible inconsistency across studies using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003; Higgins 2011a). If studies had been heterogeneous (Q statistic = 0.1 and I² statistic of 25% or greater), the review authors would have considered conducting subgroup analysis only. If we had considered the primary studies to be heterogeneous even within subgroups, we would have undertaken a narrative approach rather than a meta‐analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not use funnel plots to investigate associations between effect size and study precision in terms of sample size, because of the small number of studies included in the review. If we had included funnel plots, we would have explored the relationships observed to investigate differences between studies with large and small samples, or systematic biases, such as publication bias.

Data synthesis

For studies with a similar type of intervention or a similar active component, we performed a meta‐analysis to calculate a treatment effect across trials with a fixed‐effect model, as heterogeneity was not demonstrated. Dichotomous outcome results were available from only one study so we did not present pooled RRs. Where it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis we provided descriptive summaries of the results from each trial.

'Summary of findings' table

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using the following outcomes:

Fatigue severity and symptoms between four and 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention.

Fatigue after 12 or more weeks.

Activity limitations after 12 or more weeks.

Participation restrictions after 12 or more weeks.

Health‐related quality of life after 12 or more weeks.

Serious adverse events.

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence (studies that contribute data) for the prespecified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in Chapters 11 and 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011a; Schünemann 2011b). We used GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2008). We explained decisions to down‐ or up‐grade the quality of studies using footnotes and we made comments to aid reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Insufficient data available. See Appendix 8 for methods planned but not implemented.

Sensitivity analysis

Insufficient data available. See Appendix 8 for methods planned but not implemented.

This review has a protocol (White 2009). We listed any deviations from the protocol in Differences between protocol and review.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

The electronic and manual searches identified a total of 1386 titles and abstracts. After removing duplicates and excluding abstracts where studies were clearly not eligible for inclusion, only six full publications, four protocols and two abstracts were relevant to the review. After reading the full text of the six published articles we excluded three: two were not randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Carter 2006; Enderlin 2008) and one was an RCT of ascorbic acid for children with CMT1A in which fatigue was not an outcome (Burns 2009). We included one abstract of conference proceedings, regarding an RCT of a new low‐dose combination of three already approved drugs for CMT1A, as an ongoing trial, as the analyses are ongoing (Attarian 2013). We will include this study in future updates of this review if appropriate. Two of the other five ongoing or unpublished studies were RCTs of ascorbic acid in CMT1, and we contacted the authors for further information (NCT00484510; Verhamme 2009). However, in these ongoing studies, fatigue was not included as an outcome and we excluded them. One randomised trial of coenzyme Q10 for CMT (NCT00541164), with changes in weakness, fatigue and pain as the primary outcome, is completed but appears to be unpublished. NCT02121678 is not yet recruiting, but will study resistance training for chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy (CIDP) with the fatigue severity scale (FSS) as a planned secondary outcome. We identified one study, Ramdharry 2011, from an abstract in the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register. The study appears to be ongoing and the authors provided no data when contacted. We will include it if eligible once the full publication is available. See Characteristics of ongoing studies.

The study selection process therefore resulted in only three trials finally meeting the criteria for inclusion (Garssen 2006; Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011).

Study design and participants

We include three studies evaluating the efficacy of two drugs for fatigue in two different populations (Garssen 2006; Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011).

The first study (Garssen 2006) was a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial of amantadine for severe fatigue in 80 neurologically well‐recovered participants who had had Guillain‐Barré syndrome (GBS). Randomisation was in blocks of six with half the study participants receiving amantadine first and the remainder receiving placebo first. Interventions were followed by a two‐week washout period. Assessment of outcomes occurred on six occasions: 1: at baseline, 2: following two weeks of no intervention, 3: after six weeks of intervention 1, 4: after a two‐week washout period, 5: after six weeks of intervention 2, and finally 6: after a further two‐week washout period. Three randomised participants were withdrawn from the study in the pre‐cross‐over phase. One participant was in the placebo group and withdrew because of concern over potential side effects of amantadine when she became pregnant. The two other participants were in the amantadine treatment group; one withdrew because of hospital admission with acute cholangitis and the second participant developed severe complaints of dizziness. A further three participants were excluded from the analysis due to incorrect completion of the FSS. Therefore, 74 participants with GBS were included in the reporting of outcomes. All participants had been diagnosed with GBS between six months and 15 years previously and had no apparent changes in GBS disability score for the three months prior to entering the study. All could walk at least 10 metres with or without a walking aid (GBS disability score < 3).

The two remaining studies (Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011) were parallel‐group, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of the effect of ascorbic acid in a total of 450 adults with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A). In one, two doses (either 1 g or 3 g daily) of ascorbic acid or placebo were used in the treatment of 179 participants (Micallef 2009). Confirmation of diagnosis was by clinical examination and genotyping with duplication in 17p11.2 and at least one motor sign or symptom (gait disorder, distal amyotrophy, foot deformation or distal weakness). Block randomisation into three groups with matching for study site and sex was followed by 12 months of treatment with either 1 g or 3 g of ascorbic acid or placebo; outcomes were assessed at baseline and after 12 months of intervention. A total of 16 participants withdrew from the study after randomisation due to adverse events (six), withdrawal of consent (six), loss to follow‐up (two), non‐compliance (one) or missing baseline data (one).

Therefore, 163 participants completed the study but analysis was of all 179 participants, on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

In the second multicentre study (Pareyson 2011), the efficacy of chronic administration, for 24 months, of either 1.5 g/day ascorbic acid or placebo in the treatment of 271 participants (eligible for analysis) with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A was evaluated. Participants had a clinical diagnosis of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A with genetic confirmation of 17p11.2‐p12 duplication and a CMT neuropathy score of between 1 (excluding the electrophysiological component) and 35 (including the electrophysiological component). Block randomisation of 277 participants into groups of four stratified by disease severity and centre was followed by 24 months of treatment with either ascorbic acid or placebo, and outcomes were assessed at six‐monthly intervals from commencement of intervention until 24 months. Six participants did not receive the allocated intervention after randomisation, and are dropped from the denominators. A total of 22 participants withdrew from the intervention after commencement. Reasons for withdrawal were adverse events (13), withdrawal of consent (six), moved away from study area (two) or for personal reasons (one). Whilst the primary study outcome was based on all randomised patients who received at least one dose of the study drug using imputation for missing data the secondary analyses were conducted without imputation of missing data.

Interventions

The study of amantadine in Guillain‐Barré syndrome was a cross‐over trial in which amantadine was compared with placebo at a dose of one tablet (100 mg) daily for one week followed by two tablets daily for the remaining five weeks of each intervention period. A washout period of two weeks was incorporated before the participants shifted to the other treatment arm (amantadine or placebo) (Garssen 2006).

The studies of ascorbic acid in Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A were a parallel‐group study comparing 1 g or 3 g of ascorbic acid in a single administration of three capsules with three placebo capsules for 12 months (Micallef 2009) and a parallel‐group study comparing 1.5 g of ascorbic acid in two daily doses with placebo tablets for 24 months (Pareyson 2011).

Outcomes

In participants with severe fatigue due to Guillain‐Barré syndrome (defined as Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) 5.0 or more; FSS range 1 to 7), Garssen 2006 used a reduction of at least one point on the FSS as a primary outcome measure of fatigue. Outcomes for FSS were reported for both phases of the cross‐over study. Secondary outcome measures in the major domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) were: for structure and function, anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); for activity, impact of fatigue using the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS); and for participation, Rotterdam Handicap Scale (RHS), quality of life using the Medical Outcomes Short Form‐36 (SF‐36) Health Survey and the Euroquol Health Questionnaire (EQHQ); and adverse events.

In the studies of ascorbic acid in participants with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A, the primary outcome was CMT neuropathy score (CMTNS). Fatigue was assessed as a secondary outcome using the change in Visual Analogue Scale ‐ Fatigue (VAS‐F), either 12 months (Micallef 2009) or 24 months (Pareyson 2011) after commencement of the intervention. Secondary outcomes of activity limitation using the Overall Disability Sum Score (ODSS) (Micallef 2009) or Overall Neuropathy Limitations Scale (ONLS) (Pareyson 2011), 10 metre walk test (10MWT) Pareyson 2011 and 9 hole peg test (9HPT) (Pareyson 2011) were reported, as well as measures of participation and quality of life using the SF‐36 and adverse events in both studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

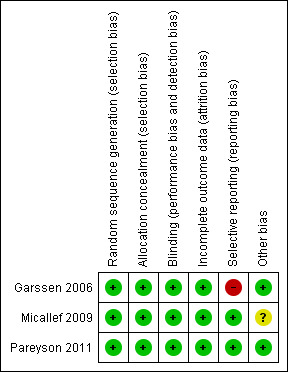

See Characteristics of included studies for details and Figure 1.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study. Key: green (+) = low risk of bias; yellow (?) = unclear risk of bias; red (‐) = high risk of bias.

Garssen 2006 conducted block randomisation in blocks of six, although allocation was concealed from researchers; we therefore considered the study to be at low risk of bias for these criteria. The trial was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study, with 80 participants initially enrolled. Although the final analysis was based on 74 participants as six were withdrawn, there was adequate reporting of the loss to follow‐up. Sample size was calculated using estimates of proportion from unpublished data obtained from a pilot study, indicating that 36 participants per group were required for 90% power at a two‐sided 5% alpha, so that with 77 participants completing the trial it was sufficiently powered to detect a difference. The washout period of two weeks between cross‐over intervention phases seems sufficient to avoid a carry‐over effect of amantadine, and is comparable with other randomised controlled cross‐over designs of efficacy for amantadine in other populations (Cohen 1989; Pucci 2009; Rosenberg 1988). The authors reported data for mean (SD) improvement in FSS scores for both amantadine and placebo treatment in both the amantadine‐placebo (0.46 (1.29), P = 0.078; 95% CI ‐0.92 to 0.05) and placebo‐amantadine sequence (0.08 (1.44), P = 0.28; 95% CI ‐1.24 to 0.44) groups and t‐test analysis for period effects and carry‐over effects were not significant. There was some evidence of selective reporting of secondary outcomes, as only P values were reported. Overall we considered the study to be at low risk of bias.

In Micallef 2009, sequence generation was conducted by an independent contract research organisation who were also responsible for concealed allocation of randomisation into blocks of 12 that were stratified for sex and study site (three sites). The trial was double‐blind with the administration of visually identical hard gelatin capsules for all groups. Analysis was on an intention‐to‐treat basis with 179 participants randomised and analysed despite 15 withdrawals prior to follow‐up (four from the placebo group, eight from the 1 g ascorbic acid group and three from the 3 g ascorbic acid group); one participant from the placebo group had missing baseline data for the study's primary outcome. All study outcomes were adequately reported. Whilst authors stated that the data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis there was no indication of how the investigators dealt with the missing data from 16 participants. Our overall summary assessment was that the study was at low risk of bias.

In the third study (Pareyson 2011), an independent randomisation unit was responsible for sequence generation and group allocation stratified for disease severity and treatment centre in blocks of four. This, combined with the use of placebo tablets of identical appearance, taste and smell, resulted in blinding of participants, researchers and treating physicians. Six participants randomised to the intervention (four participants) and placebo (two participants) groups withdrew consent before receiving the allocated intervention and were excluded from analysis. Although the investigators recorded outcome data at six‐monthly intervals for 24 months, the authors stated that their main analysis would be at 24 months, and reported the primary outcome at only 12 and 24 months and the secondary outcomes only at 24 months. Overall we considered this study to be at low risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

Amantadine versus placebo in Guillain‐Barré syndrome

Effect estimates, where data were available, were obtained from a single trial, so we downgraded the quality of evidence for all outcomes for this reason (Table 1).

Primary outcome

Fatigue between four and 12 weeks after commencement of intervention

Garssen 2006 assessed baseline measures at visit 1 and at visit 2, prior to randomisation. In the 74 participants for whom full outcome data were reported, there was evidence of a reduction in fatigue between these baseline visits, which was stated by the authors to approach significance (P = 0.05 Wilcoxon signed rank test), although complete group data were not presented. The magnitude of fatigue reduction before the start of any intervention was such that although the median FSS score for the 74 participants was 5.9 at visit 2, seven (9%) of the participants had an FSS score lower than the inclusion criterion of FSS 5 for severe fatigue.

Thirty‐six participants received amantadine followed by placebo and 38 received placebo followed by amantadine. Favourable outcome reporting was available for both phases of each treatment sequence, representing evaluation of the primary outcome six weeks after the commencement of intervention. Results were presented as the mean difference (MD) in reduction in FSS scores between amantadine and placebo, and as an odds ratio (OR) of a favourable outcome (defined as a reduction of more than 1 in FSS score). The overall MD in FSS score between amantadine and placebo phases was ‐0.45 (95% CI ‐0.94 to 0.04; t = ‐1.80; df = 73; P = 0.076). When the participants responding favourably to one treatment only in both the group receiving amantadine followed by placebo (amantadine‐placebo group) and those receiving placebo followed by amantadine (placebo‐amantadine group) were combined, the number with a more favourable outcome following amantadine was 9 of 25 (36%) participants with an OR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.35, P = 0.16) using the McNemar test.

Secondary outcomes

All stated secondary outcomes in Garssen 2006 were only reported at six weeks after commencement of the intervention and therefore not at the stated secondary outcome point of 12 or more weeks after commencement of intervention for this review. In addition full data for the study secondary outcomes were not available, as only P values were provided (Garssen 2006). The data indicated that there was no significant improvement in: fatigue impact using the fatigue impact scale (FIS) (P = 0.77); participation using the Rotterdam Handicap Scale (RHS) (P = 0.14) and Euroquol Health Questionnaire (EQHQ) (P = 0.21) at six weeks. The authors reported that quality of life using the SF‐36 demonstrated a significant improvement in physical role functioning (P = 0.008) and mental health perception (P = 0.008), although only in the placebo group (Garssen 2006). We contacted the authors for further information about secondary outcomes; the RHS scores for participation at six weeks from the original data were provided by the trial author (Garssen 2006). The data were analysed using a paired two‐sample t‐test and showed that the MD between the change in participation with placebo versus the change with amantadine between four to 12 weeks after commencement of intervention was 0.31 (95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.72, P = 0.13) (Table 3). (Table 1).

1. Data and analysis: amantadine versus placebo.

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Statistical method | Effect estimate |

| Change in participation (using the Rotterdam Handicap Scale) > 12 weeks after commencement of intervention | 1 (cross‐over) | 74 | Mean difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [‐0.09 to 0.72] |

Fatigue after 12 or more weeks

Not reported at this time point.

Activity limitations after 12 or more weeks

Not reported at this time point.

Participation restrictions after 12 or more weeks

Not reported at this time point.

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) after 12 or more weeks

Not reported at this time point.

Adverse events

Reported in Garssen 2006.

No serious adverse events were reported. However, mild, transient adverse effects were reported in 32 out of 80 (40%) participants: 22 participants during amantadine treatment and 10 during placebo treatment. Adverse effects included anticholinergic complaints (six participants: three in each treatment group), gastrointestinal complaints (10 participants: seven in placebo group and three in amantadine group), sleep complaints (10 participants: nine in amantadine group and one in placebo group) and other less frequent side effects (headache, feelings of nervousness and vivid dreams). No side effects were reported to have affected trial participation.

Ascorbic acid versus placebo in Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease

Primary outcome

Fatigue between four and 12 weeks after commencement of intervention

Neither study evaluating ascorbic acid for Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A reported change in fatigue within the time scale of the primary outcome for this review (Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011).

Secondary outcomes

Data for secondary outcomes were reported at 12 months after commencement of the intervention in Micallef 2009 and at 24 months after commencement of the intervention in Pareyson 2011. Where two different doses of ascorbic acid were used in Micallef 2009, we combined data from both intervention arms, including participants receiving a higher dose (3 g ascorbic acid) and those receiving a lower dose (1 g ascorbic acid) in comparisons for all outcomes.

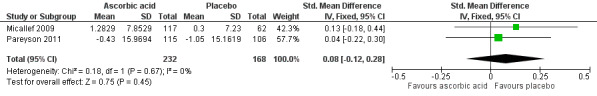

Fatigue after more than 12 weeks

Reported in Micallef 2009 and Pareyson 2011.

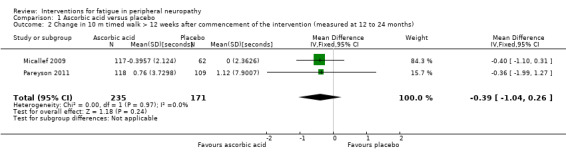

Both studies assessed fatigue using change in Visual Analogue Scale for fatigue (VAS‐F). Fatigue was assessed at 12‐month follow‐up using a 0 to 100 VAS for fatigue in Micallef 2009 and at 24‐month follow‐up using a 0 to 10 VAS for fatigue in Pareyson 2011. The pooled estimate of effect of the change in fatigue more than 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention was standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.12 (95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.08, P = 0.25; N = 404; I² = 0%) (see Analysis 1.1; Figure 2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 1 Change in fatigue > 12 weeks after commencement of intervention (measured at 12 to 24 months) (VAS 0 ‐ 10 or 0 ‐ 100).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Change in fatigue > 12 weeks after commencement of intervention at 12 months [VAS 0 ‐ 100).

Activity limitations after 12 or more weeks

Reported in Micallef 2009 and Pareyson 2011.

Activity limitation was assessed using the ODSS at 12 months after commencement of intervention in Micallef 2009 and the Overall Neuropathy Limitations Scale (ONLS) 24 months after commencement of intervention in Pareyson 2011. Pooling of data in a meta‐analysis was not possible since data for ordinal scale scores were presented as medians plus interquartile ranges (IQRs), and there was no indication of whether the data were skewed. However, the authors reported that there was no significant difference (P = 0.22) in median change in activity limitation between placebo and 1 g or 3 g doses of ascorbic acid at 12 months in Micallef 2009, and no significant difference (P = 0.99) in median change in activity limitation between placebo and 1.5 g dose of ascorbic acid in Pareyson 2011.

In addition, further measures of activity limitation were included in both studies. The 10MWT was measured in both Micallef 2009 and Pareyson 2011 (at 12 months and 24 months, respectively) and the pooled estimate of effect for change in time taken to walk 10 metres more than 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention was MD ‐0.39 (95% CI ‐1.04 to 0.26, P = 0.24; N = 406; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 3). In addition the 9HPT was measured in Pareyson 2011 at 24 months and showed that there was no significant effect of ascorbic acid (MD ‐0.74, 95% CI ‐1.60 to 0.12, P = 0.09; N = 224) (Analysis 1.3).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 2 Change in 10 m timed walk > 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention (measured at 12 to 24 months).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Change in 10 m timed walk > 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention (measured at 12 to 24 months) [seconds].

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 3 Change in speed of completion of 9 hole peg test > 12 weeks after commencement of intervention (measured at 24 months).

Participation restrictions after 12 or more weeks

Not reported in Micallef 2009 or Pareyson 2011.

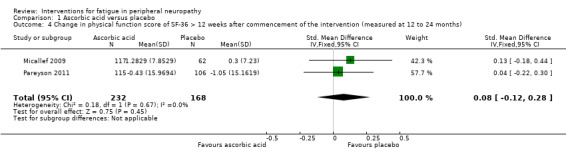

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) after 12 or more weeks

Reported as an outcome and assessed using the SF‐36 at 12 months after commencement of the intervention in Micallef 2009 and 24 months after commencement of the intervention in Pareyson 2011. We calculated a pooled estimate of the change in physical functioning, as measured by the Physical Component Score (PCS) in Micallef 2009 and the Physical Function Scale (PFS) of the SF‐36 in Pareyson 2011. Using data from 400 participants, the SMD was 0.08 (95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.28) favouring placebo (see Figure 4, Analysis 1.4). There was no significant statistical heterogeneity, despite the difference in duration of follow‐up (I² = 0%, P = 0.67).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, outcome: 2.4 Change in physical function score of SF‐36.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 4 Change in physical function score of SF‐36 > 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention (measured at 12 to 24 months).

Micallef 2009 reported HRQoL assessed by the Mental Component Score of the SF‐36 and for this too there was no significant difference (P = 0.77) between either dose of ascorbic acid versus placebo or in a combined analysis, between both doses of ascorbic acid versus placebo, 12 months after the start of treatment (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 5 Change in mental function score of SF‐36 > 12 weeks after commencement of the intervention (measured at 12 months).

Adverse events

Reported in Micallef 2009 and Pareyson 2011.

In Micallef 2009, 896 adverse events were documented in 158 (89%) participants (55 of 62 participants in the placebo group (89%); 47 of 56 participants in the 1 g ascorbic acid group (89%), and 56 of 61 participants in the 3 g ascorbic acid group (92%)), of which only 24 were serious adverse events. Serious adverse events were recorded in 22 participants (eight in the placebo group, seven in the 1 g ascorbic acid group and seven in the 3 g ascorbic acid group). Researchers deemed the majority of events (70%) not to be related to treatment and 208 (25%) to have a possible relation to treatment, of which only 12 (11 listed in the report) were severe: upper abdominal pain (2), dyspepsia (2), headache (1), insomnia (1), muscle spasm (1), musculoskeletal stiffness (1), rash (1), rhinitis (1) and sleep disturbance (1). Six participants (one in the placebo group, four in the 1 g ascorbic acid group and one in the 3 g ascorbic acid group) gave adverse events (cystitis, myalgia, depression, colitis and insomnia) as reasons for withdrawal from the study.

In Pareyson 2011, 21 serious adverse events were documented in 20 participants (eight events in seven of 138 participants in the ascorbic acid group and 13 events in 13 of 133 participants in the placebo group). Researchers considered all but one event, where a woman in the placebo group was admitted to hospital due to anaemia, as unrelated to the intervention. Thirteen participants experiencing adverse events were lost to follow‐up (six in the placebo group and seven in the ascorbic acid group), and eight participants (six in the placebo group and two in the ascorbic acid group) ceased treatment as a result of a serious adverse event. Five of these eight continued with follow‐up and three (two receiving placebo and one receiving ascorbic acid) withdrew from the study. Adverse events in those who discontinued the interventions included gastralgia, abdominal cramps or diarrhoea (9), surgery (4), renal colic (1), pregnancy (3), rectal bleeding (1), saccharine intolerance (1) and gum disease (1). The pooled risk ratio (RR) for serious adverse events in studies of ascorbic acid for CMT1A was 0.70 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.27, P = 0.24; N = 450; I² = 0%) (see Analysis 1.6, Figure 5), indicating no significant difference in serious adverse events between ascorbic acid and placebo.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 6 Serious adverse events.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Ascorbic acid versus placebo, outcome: 2.6 Adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our search identified three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that met the inclusion criteria. The trials evaluated the effect of two different drugs on fatigue in two different populations of people with peripheral neuropathy. Two studies examined the effect of different doses of ascorbic acid in Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A, and therefore no combined analysis was possible.

The first study (Garssen 2006) was a block‐randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over study of amantadine for severe fatigue in 74 neurologically stable participants at least six months after Guillain‐Barré syndrome. We judged the risk of bias of the trial to be low. The study reported a moderate reduction in fatigue severity scale (FSS) score for participants treated with amantadine but the confidence interval was wide and study size relatively small, suggesting that the study may have been underpowered to detect a difference; we therefore graded the quality of the evidence as low. These data indicate that larger studies might improve the power to detect a reduction in risk of fatigue with amantadine. Nevertheless, the mean difference (MD) did not exceed the minimal clinically important difference for change in FSS scores estimated for people with systemic lupus erythematosus (MD 0.6; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.9), indicating that it is likely that there is no effect of amantadine compared with placebo in the treatment of severe fatigue (see Table 1). A significant decrease in fatigue was noted between two pre‐treatment baseline visits two weeks apart. Since the participants were considered to be neurologically stable, this suggests that increased attention to people with fatigue due to Guillain‐Barré syndrome may improve symptoms of fatigue.

The two studies evaluating ascorbic acid for Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth (CMT) disease 1A were block‐randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of different doses of ascorbic acid for the treatment of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A (Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011). The risk of bias for Micallef 2009 was low, despite the fact that there was no report of how missing data were dealt with in the intention‐to‐treat analysis. All other aspects of risk of bias assessment were adequate. The main findings were that whilst ascorbic acid was well‐tolerated and safe for adults with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A over a period of 12 months, there were no significant differences in effect across all outcomes, including fatigue, between placebo, 1 g or 3 g of ascorbic acid (see Table 2). There was a low risk of bias in the remaining study (Pareyson 2011), and the main findings were that ascorbic acid supplementation at a dose of 1.5 g per day for 24 months was well tolerated but there was no significant effect on neuropathy or secondary outcomes compared with placebo.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only three RCTs (Garssen 2006; Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011) were eligible for inclusion in the review. One was of amantadine for severe fatigue in Guillain‐Barré syndrome and the others were of three different doses of ascorbic acid for people with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A. RCTs evaluating the effect of other interventions for fatigue, such as other drugs; pacing and grading of physical activity; general or specific exercise; compensatory strategies such as orthotics; relaxation; counselling; cognitive and educational strategies; and interventions for fatigue that form part of a multidimensional programme, or trials of interventions for other causes of peripheral neuropathy, were not available. None of the included studies considered the cost effectiveness of interventions for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy

Quality of the evidence

The overall risk of bias in the included trials (Garssen 2006; Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011) was low.

Garssen 2006 reported a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study, where, despite a block randomisation procedure affecting bias in sequence generation and incomplete reporting of secondary outcomes, there was effective allocation concealment and P values for secondary outcomes were available. Reporting of data for fatigue during both phases of the trial indicates that there was no significant carry‐over effect. We therefore judged the overall risk of bias to be low.

Micallef 2009 reported a block‐randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study, where all assessed aspects of risk of bias were adequate except for the lack of reporting of how missing data were dealt with for an intention‐to‐treat analysis. We therefore judged the overall risk of bias to be low.

Pareyson 2011 reported a block‐randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study with a low risk of bias overall.

Since only one trial of amantadine for the treatment of fatigue in Guillain‐Barré syndrome (Garssen 2006) and two trials of ascorbic acid for treatment of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A (Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011) are included in the review, it is not possible to address the review objectives for drug or other interventions. The Garssen 2006 study was relatively small (74 participants) and the results actually suggest that there may be an effect, but the study is under‐powered. We downgraded the evidence from this study to low because of its imprecision (Table 1). Larger studies including those with different doses and frequency of administration of amantadine are desirable before a definite conclusion about the effect of amantadine to treat fatigue in peripheral neuropathy and in particular in Guillain‐Barré syndrome can be given.

The studies of ascorbic acid for Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A were larger, and evaluated the effect of three different doses of ascorbic acid in Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A (Micallef 2009; Pareyson 2011). The lack of reporting of how missing data were dealt with in Micallef 2009 means that it is difficult to assess whether the risk of bias is likely to have favoured the control or ascorbic acid treatment groups in this study . Nevertheless, the low risk of bias associated with the final study (Pareyson 2011) and the fact that it has similar findings to Micallef 2009 meant that we did not downgrade the evidence because of trial design or conduct, but did downgrade it because of the lack of reporting of how missing data was dealt with in Micallef 2009. This means that there is moderate‐quality evidence suggesting that ascorbic acid has no benefit in the treatment of fatigue in CMT (See Table 2).

The primary outcome of fatigue was evaluated using the FSS or VAS for fatigue in the included studies. The FSS is based on classical test theory (CTT), where scales may include items not relevant for particular clinical populations, and scale sum scores assume equal weighting of items where this has not necessarily been demonstrated. This potentially introduces bias into the assessment of the underlying outcome of interest. However, evidence in the current review was not downgraded due to directness based on outcomes used, since the effect of indirectness is not currently known. Nevertheless, clinicians and researchers are moving towards linearly weighted scales based on modern scientific methods such as Rasch models or item response theory (IRT) for evaluation of outcomes in clinical populations. The FSS has recently been fully evaluated and modified using the Rasch unidimensional measurement model (RUMM2020) and is recommended for use in immune‐mediated neuropathy (van Nes 2009). Its relevance for other peripheral neuropathies remains to be evaluated.

Potential biases in the review process

Two review authors were also investigators in an included trial (Garssen 2006), but neither was involved in assessing the risk of bias in this study.

We contacted study authors where there were missing data, and these was provided by Garssen 2006 for one secondary outcome. We also contacted authors of published abstracts with limited reporting of data for further information, but they either did not reply or declined to, stating their intention to publish a full report of the study in the future as a reason.

This systematic review used an adequate search strategy to avoid missing any RCTs on treatments for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy. There were no language restrictions in our searches, and whilst a limitation of the review is that we did not initially plan in our protocol to search clinical trials registers, this additional search was subsequently conducted; this difference between the protocol and review is flagged up below.

The criteria for types of participants for including studies accepted the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy offered by the authors, provided that it stipulated the presence of clinical impairment characteristic of peripheral neuropathy. We considered only sensory, motor or combined sensory and motor peripheral neuropathies, and excluded studies of participants with focal entrapment neuropathies with pain as the primary presenting feature, and with poliomyelitis. There is therefore a small possibility that misdiagnosis of participants may have affected study inclusion, and that studies with mixed populations of participants that include both sensory, motor and combined sensory motor neuropathies as well as painful entrapment neuropathies or poliomyelitis were excluded. This could be a potential source of selection bias in the review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are currently no other systematic reviews of interventions for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy available, despite many treatments for fatigue including: drugs, pacing and grading of physical activity, general or specific exercise, compensatory strategies such as orthotics, relaxation, counselling, cognitive and educational strategies, either alone or as part of a multidimensional programme.

Systematic reviews of interventions for fatigue in other conditions

In the absence of evidence from reviews or high‐quality RCTs in peripheral neuropathy it may be helpful to consider the effect of interventions for fatigue in other conditions, including chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), fibromyalgia, multiple sclerosis and cancer‐related fatigue. The high incidence of anxiety and depression in functional somatic syndromes such as fibromyalgia and CFS (Henningsen 2003) and the specific pathophysiological features of multiple sclerosis and cancer‐related fatigue mean that recommendations from systematic reviews should be considered with caution. In all cases we included only evidence from Cochrane systematic reviews.

Drugs for fatigue

The evidence from Cochrane systematic reviews of drugs in the treatment of fatigue in other conditions was of varying quality. A systematic review of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for fibromyalgia indicated that they only provide a small improvement in fatigue (1.7% improvement) over placebo (Hauser 2013). In reviews of amantadine or carnitine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis, the poor quality of the available RCTs meant that no conclusion regarding their efficacy could be drawn (Pucci 2009; Tejani 2012). Finally, whilst the updated systematic review of drug therapy for the management of cancer‐related fatigue provides evidence that psychostimulant trials may give a clinically meaningful improvement in cancer‐related fatigue, new safety data indicate that the drugs are associated with increased adverse outcomes and they can no longer be recommended in the treatment of cancer‐related fatigue (Minton 2010).

Non‐drug interventions for fatigue

We reviewed the evidence from recent Cochrane systematic reviews of non‐drug interventions for fatigue in other conditions, which suggests that exercise (Edmonds 2004) and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Price 2008) for fatigue in CFS are both better than usual care, with the evidence for CBT being more extensive and robust than for exercise. In a review of exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome, there is very limited evidence that aerobic‐only exercise is likely to have no effect on fatigue in individuals with fibromyalgia (Busch 2007). A systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapies for fibromyalgia concludes that there was only a 5.8% (95% CI 0.05 to 11.3) effect on fatigue (Bernardy 2013). A systematic review of exercise for management of cancer‐related fatigue concluded that aerobic exercise is beneficial (Cramp 2012).

Evidence from individual studies of interventions for fatigue in neuropathy

One article describing an uncontrolled case series of people with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A treated with modafinil for fatigue reported that all four participants had less fatigue within at least 10 days of commencing modafinil treatment (Carter 2006). The case study design means that this report has substantial risk of bias but may suggest that modafinil is a potentially useful drug for fatigue in people with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A, and merits well‐designed trials.

The wide variety of causes and consequences in peripheral neuropathy, combined with a relatively low prevalence of individual conditions means that controlled trials of non‐drug interventions have been limited. In addition, despite the substantial prevalence of fatigue in people with peripheral neuropathy (Merkies 1999), subjective fatigue is not routinely evaluated in RCTs and other study designs of such interventions. However, one cohort study (Garssen 2004) and one case‐control study (Graham 2007) of exercise for people with Guillain‐Barré syndrome and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) reported significant reductions in fatigue after 12 weeks of either supervised aerobic cycling (Garssen 2004) or unsupervised community‐based exercise (Graham 2007). Whilst these studies are subject to very high risks of bias due to their design, they may suggest that RCTs of exercise for people with fatigue due to peripheral neuropathy should be conducted.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence from randomised controlled trials of the efficacy of interventions for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy is limited. One small study comparing amantadine with placebo for fatigue in people with Guillain‐Barré syndrome was not sufficiently powered to determine the effects on fatigue in this population. There was moderate quality evidence that the effects of ascorbic acid on fatigue in people with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A are small. Information about adverse effects was limited, although both treatments appeared to be well tolerated in these conditions.

There was no evidence available from randomised controlled trials to evaluate the effect of other interventions for fatigue in either Guillain‐Barré syndrome, Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease 1A or other causes of peripheral neuropathy.

Implications for research.

The dearth of evidence from high‐quality randomised controlled trials on the effects of interventions for fatigue in peripheral neuropathy indicates that treatments for this condition warrant further research. Trials in relevant patient populations should have adequate sample size, appropriate randomised controlled designs and clinically relevant standardised and responsive measures of fatigue as an outcome.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 December 2014 | Amended | Correction to plain language title |

Acknowledgements

The staff of the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group (CNMDG). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the CNMDG developed search strategies in collaboration with the review authors and provided the literature searches. Editorial support from the CNMDG is supported by funding from the MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to October Week 4 2013> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 randomized controlled trial.pt. (388634) 2 controlled clinical trial.pt. (89809) 3 randomized.ab. (286167) 4 placebo.ab. (156455) 5 drug therapy.fs. (1763008) 6 randomly.ab. (198817) 7 trial.ab. (301285) 8 groups.ab. (1272819) 9 or/1‐8 (3290381) 10 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4054690) 11 9 not 10 (2801675) 12 exp Peripheral Nervous System Diseases/ (124752) 13 (neuropath$ or polyneuropath$).mp. (105405) 14 12 or 13 (185586) 15 Fatigue/ or fatigue.mp. (65961) 16 (tired$ or weariness or weary or exhaust$ or lacklustre or astheni$ or lethargic or languidness or languor or lassitude or listlessness).mp. (44221) 17 ((lack or loss or lost) adj2 (energy or vigour or vigour)).mp. (2987) 18 15 or 16 or 17 (108926) 19 14 and 18 (1830) 20 exp Exercise Therapy/ (30220) 21 exp Physical Therapy Modalities/ (124257) 22 rehabilitation.mp. or Rehabilitation/ (111245) 23 (exercise or train or activity or physical or exercise or strength or sports or isometric or isotonic or isokinetic or endurance or kinesiotherap$).mp. (2842549) 24 relaxation therapy/ (5777) 25 (exercise adj2 (grading or pacing)).mp. (175) 26 behavior therapy/ (24012) 27 orthotic devices/ (5122) 28 exp drug therapy/ (1119005) 29 cognitive therapy/ (16072) 30 or/20‐29 (3976732) 31 11 and 19 and 30 (786) 32 exp *neoplasms/ (2240467) 33 31 not 32 (156) 34 remove duplicates from 33 (137)

Appendix 2. EMBASE (OvidSP) search strategy

Database: Embase <1980 to 2013 Week 44> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 crossover‐procedure.sh. (38843) 2 double‐blind procedure.sh. (118442) 3 single‐blind procedure.sh. (18456) 4 randomized controlled trial.sh. (359225) 5 (random$ or crossover$ or cross over$ or placebo$ or (doubl$ adj blind$) or allocat$).tw,ot. (1012298) 6 trial.ti. (154806) 7 or/1‐6 (1149945) 8 (animal/ or nonhuman/ or animal experiment/) and human/ (1317960) 9 animal/ or nonanimal/ or animal experiment/ (3490108) 10 9 not 8 (2874827) 11 7 not 10 (1054428) 12 limit 11 to embase (818020) 13 exp Peripheral Nervous System Diseases/ (49376) 14 (neuropath$ or polyneuropath$).mp. (212283) 15 13 or 14 (212616) 16 Fatigue/ or fatigue.mp. (142546) 17 (tired$ or weariness or weary or exhaust$ or lacklustre or astheni$ or lethargic or languidness or languor or lassitude or listlessness).mp. (78274) 18 ((lack or loss or lost) adj2 (energy or vigour or vigour)).mp. (4598) 19 16 or 17 or 18 (213642) 20 15 and 19 (11641) 21 exp Exercise Therapy/ (45680) 22 exp Physical Therapy Modalities/ (51094) 23 rehabilitation.mp. or Rehabilitation/ (170481) 24 (exercise or train or activity or physical or exercise or strength or sports or isometric or isotonic or isokinetic or endurance or kinesiotherap$).mp. (3724423) 25 relaxation therapy/ (8322) 26 (exercise adj2 (grading or pacing)).mp. (193) 27 behavior therapy/ (36705) 28 orthotic devices/ (4385) 29 exp drug therapy/ (1577772) 30 cognitive therapy/ (32204) 31 or/21‐30 (5209900) 32 12 and 20 and 31 (2553) 33 remove duplicates from 32 (2548) 34 exp *neoplasm/ (2511133) 35 33 not 34 (594)

Appendix 3. CINAHL (EBSCOhost) search strategy