Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a lethal pathogen that can cause various bacterial infections. This study targets the CrtM enzyme of S. aureus, which is crucial for synthesizing golden carotenoid pigment: staphyloxanthin, which provides anti-oxidant activity to this bacterium for combating antimicrobial resistance inside the host cell. The present investigation quests for human SQS inhibitors against the CrtM enzyme by employing structure-based drug design approaches including induced fit docking (IFD), molecular dynamic (MD) simulations, and binding free energy calculations. Depending upon the docking scores, two compounds, lapaquistat acetate and squalestatin analog 20, were identified as the lead molecules exhibit higher affinity toward the CrtM enzyme. These docked complexes were further subjected to 100 ns MD simulation and several thermodynamics parameters were analyzed. Further, the binding free energies (ΔG) were calculated for each simulated protein–ligand complex to study the stability of molecular contacts using the MM-GBSA approach. Pre-ADMET analysis was conducted for systematic evaluation of physicochemical and medicinal chemistry properties of these compounds. The above study suggested that lapaquistat acetate and squalestatin analog 20 can be selected as potential lead candidates with promising binding affinity for the S. aureus CrtM enzyme. This study might provide insights into the discovery of potential drug candidates for S. aureus with a high therapeutic index.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03862-y.

Keywords: Anti-virulence, CrtM, Docking, MM-GBSA, Molecular dynamics, Staphyloxanthin virtual screening

Introduction

One of the major challenges of the twenty-first century is the advent of multiple drug resistance in pathogenic bacteria against the known antibiotics (Singh et al. 2022). Staphylococcus aureus is one of the main pathogens causing a variety of hospital- and community-acquired infections that can lead to various diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, and toxic shock syndrome (Dalal et al. 2021; Kumari et al. 2022). Virulence factors are pathogenic products that help the pathogen evade the host immune system. Anti-virulence therapy has been considered as an alternative method to combat the resistance against conventional antibiotic therapy. S. aureus is a Gram-positive bacterium that produces 17 different triterpenoid carotenoids (Aribisala and Sabiu 2022). These carotenoids possess a C30 chain with alternating single and double bonds as compared to C40 chains found in most other organisms. Dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) is involved in the synthesis of staphyloxanthin which is the most recognized membrane-associated carotenoid pigment, contributes to golden pigment that provides anti-oxidant property to the S. aureus, and enables its survival within the host cell (Banu et al. 2018). The production of Staphyloxanthin occurs in a 5-step enzymatic reaction starting with dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) that catalyzes the condensation of two farnesyl diphosphate molecules to produce presqualene diphosphate, followed by two stepwise oxidation reactions catalyzed by 4,4′-diapophytoene desaturase (CrtN) and 4,4′-diaponeurosporene oxidase (CrtP) and two glucose esterification steps at C1″ and C6″ positions catalyzed by glycosyltransferase (CrtQ) and acyltransferase (CrtO), respectively (Sullivan et al. 2021).

It has been reported that there is a 30% sequence identity between the human squalene synthase (SQS) and dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) S. aureus, and they share substantial structural features (Gao et al. 2017). The structural similarity between human SQS and CrtM suggests that human SQS inhibitors available as cholesterol-lowering drugs might also be active against CrtM. Previous in vitro studies were focused on the application of cholesterol inhibitors as anti-virulence drugs against S. aureus offering a proof-of-principal for a virulence-targeted approach by blocking staphyloxanthin production resulting in rapid clearance in a mouse infection model (Liu et al. 2008). Hence, the findings of the previous study suggest the possibility of inhibiting the biosynthetic pathway of staphyloxanthin by various SQS inhibitors. Considering the above facts, an in silico approach was used to explore the molecular interactions between the lead compounds and the binding site S. aureus dehydrosqualene synthase.

In the present study, we used a combined molecular modeling approach on human SQS inhibitors to investigate the mechanism of inhibitor binding with S. aureus CrtM enzyme. Molecular docking is an extensively used method for the calculation of protein–ligand interactions in the drug discovery process (Metwaly et al. 2022). The structural interactions between the protein (PDB ID: 3W7F) and seven inhibitors (lapaquistat acetate and squalestatin analogs) were docked separately using Induced Fit Docking (IFD) for the accurate prediction of ligand-binding mode and estimation of docking score. To investigate further, the functionalities of active molecular interaction between the inhibitor and the catalytic pocket residues and to analyze the stability of the protein–ligand complex, an explicitly solvated 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed (Che Omar 2020). The binding free energy of the protein–ligand complex was calculated by the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA). However, to understand the role of individual amino acid involvement in the mechanism of binding, residue energy decomposition analysis was performed. Furthermore, the test compounds were screened based on ADMET properties by ADMETlab 2.0 and pre-ADMET (Husain et al. 2016). The current work is an extension of the research conducted by the same group Kahlon et al. 2010. We carried out an in-depth analysis and came up with additional findings.

Materials and methods

Protein preparation

The crystal structures of the C (30) carotenoid dehydrosqualene synthase from S. aureus (PDB Id: 3W7F) were retrieved from RCSB protein databank (https://www.rcsb.org/) (Berman et al. 2000). The structure of 3W7F contains two identical chains in the unit cell and chain A having 293 amino acid residues complexed with Farnesyl Thiopyrophosphate (S-[(2E,6E)-3,7,11-trimethyldodeca-2,6,10-trienyl] trihydrogen thiodiphosphate), and magnesium ion with a resolution of 2.25 Å is used for molecular docking studies. Before docking, the protein structure was prepared using Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrodinger’s Maestro 2022-4 2022). During protein preparation, heteroatoms, ligands, and crystal waters were removed. Polar hydrogens were added and partial charges were assigned using the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS4) force field.

Selection of target molecules and ligand preparation

3D conformers of cholesterol-lowering drugs viz. Lapaquistat acetate (PubChem ID: 9874248); Squalestatin analog 2 (PubChem ID: 460617), Squalestatin analog 15 (PubChem ID: 460618), Squalestatin analog 20 (PubChem ID: 460623), Squalestatin analog 25 (PubChem ID: 460628), Squalestatin analog 32 (PubChem ID: 460,634), and Squalestatin analog 36 (PubChem ID: 460638) were downloaded from PubChem database (Kim et al. 2016) in SDF format. Ligands were prepared using the LigPrep (LigPrep Schrödinger Release 2022–4 2022) module of Schrodinger’s Maestro which corrects the protonation and ionization states of the compounds and assigns proper bond orders. Subsequently, the tautomeric states and the ring conformations/ionization states were generated for each ligand.

Molecular docking studies

The molecular docking studies were conducted via the Induced Fit Docking (IFD) module of Schrodinger’s Maestro 2022–4 (2022). A grid box was generated by selecting the co-crystallized ligand and subsequently, the native inhibitor of the 3W7F and all the selected compounds were docked into the active site of the protein using the standard precision (SP) glide method to obtain the docking score and glide energy. The docked complexes were then analyzed through 2D ligand interaction diagrams and important bonds were also analyzed.

MD simulation studies

For further validation of the docking results, top-scoring poses were assessed by all-atom molecular dynamics simulations using Desmond module of Schrodinger’s Maestro 2022-4 (Desmond Molecular Dynamics System 2021). The system was solvated in an orthorhombic box of the SPC water model, and 0.15 M NaCl was added to neutralize its charge. The system was equilibrated under NPT ensemble class for 100 ns at 300 K and 1.01325 bar, and all other parameters were set as default.

Binding energy calculation and residue decomposition

The binding energy calculations were carried out by the Prime MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) tool (Prime, Schrödinger Release 2022–4 2022) included in Schrodinger’s Maestro (Elmesseri et al. 2022). The net binding energy was computed using the ther-mal_mmgbsa.py script, and residue-wise free energy calculations were performed through the breakdown_MMGBSA_by_residue.py script included in the Prime module (Choudhary et al. 2020). The overall binding free energy calculation is expressed as:

The breakdown_MMGBSA_by_residue.py script uses the output obtained from MM-GBSA and calculates the average free energy contribution of each residue (Table 1S).

Analysis of protein tunnels and ligand transport

The analysis of protein tunnels/channels and ligand transport was performed using the Caver Web v1.1 (https://loschmidt.chemi.muni.cz/caverweb/) web server (Stourac et al. 2019). It is a comprehensive tool that can perform tunnel analysis and ligand transport through these tunnels within a single environment (Musil et al. 2022). The input files include the molecular structure in pdb format and the potential inhibitor in mol2 format. After execution of the calculation, it provides output as visualization of tunnels and channels, trajectories of ligand passage, and energy profiles of the potential drugs (Tables 2S and 3S).

ADMET analysis

To eliminate the failure at later stages of drug discovery, all the test compounds were analyzed based on druglikeness properties using in silico ADMET analysis. The ADMET module is based on atomic logP98, polar surface area (PSA), blood–brain barrier (BBB), cytochrome P450, hepatotoxicity, bioactivity, and human oral absorption. The ADMET properties were predicted through the ADMETlab 2.0 online platform (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) (Xiong et al. 2021), and the compounds were tested based on the properties including BBB penetration, MDCK permeability, Caco-2 permeability, HERG blockers, PAINS, Lipinski rule, skin sensitization, eye corrosion, T1/2, human intestinal absorption (HIA), etc. On the other hand, the toxicity prediction of the compounds was done through PreADMET (Lee et al. 2003) based on properties, such as AMES test, Carcino mouse, Acute algae toxicity, Acute daphnia toxicity, and Acute fish toxicity, etc. (Table 4S).

Results

Molecular docking studies through IFD

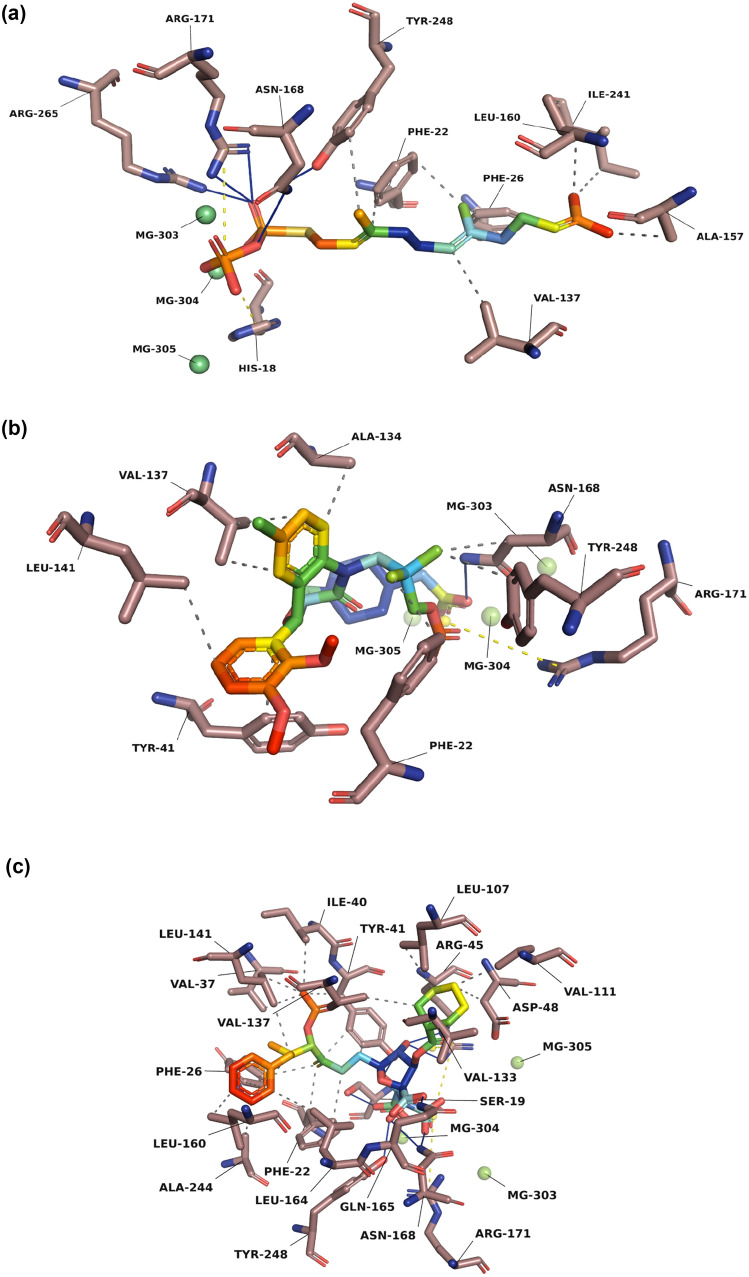

To understand the dynamics of interacting residues, all the selected ligands viz., lapaquistat acetate and squalestatin analogs were docked against the active site of dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) (Protein Id 3W7F) as shown in Fig. 1a–c. The interaction of CrtM with cholesterol-lowering drugs was proposed through the IFD module of Schrodinger’s Maestro, and the best pose obtained in terms of docking score with important interacting residues involved in the binding is given in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Overlay of 3D interaction diagrams of standard compound a Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate and top two test compounds b Lapaquistat acetate and c Squalestatin analog-20. The protein residues are shown as copper-colored sticks and the ligand molecules were represented as rainbow sticks model, solid blue line indicate the H bonds with backbone residues, dotted gray line represent hydrophobic interactions, whereas dotted yellow line show salt bridges

Table 1.

Induced fit docking results of standard and test compounds with different scores and interacting residues

| SI. No | PDB ID | Compound ID | Compound name | IFD score (kcal/mol) | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Glide energy (kcal/mol) | Glide e-model (kcal/mol) | H-Bond interacting residues | Other interacting residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3W7F | 657041 | *Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate | − 394.78 | − 10.600 | − 99.513 | − 294.179 | ASN_168; ARG_171; ARG_265 | Salt Bridges: ARG_171; ARG_265 |

| 2 | 3W7F | 9874248 | #Lapaquistat Acetate | − 683.59 | − 15.637 | − 103.744 | − 237.490 | ASN_168 | Pi-pi: TYR_41 |

| 3 | 3W7F | 460617 | #Squalestatin analog 2 | − 395.40 | − 13.203 | − 115.259 | − 363.232 | GLN_165; ASN_168; ARG_171 |

Salt Bridges: ARG_171; ARG_265 Pi-pi: PHE_22; PHE_26 |

| 4 | 3W7F | 460618 | #Squalestatin analog 15 | − 668.29 | − 13.508 | − 119.523 | − 393.416 | ARG_45; GLN_165; ASN_168; ARG_171 | Salt Bridges: ARG_45; ARG_171 |

| 5 | 3W7F | 460623 | #Squalestatin analog 20 | − 672.60 | − 15.413 | − 114.143 | − 345.830 | SER_19; ARG_45; GLN_165; ASN_168; ARG_171 |

Salt Bridges: ARG_45; ARG_171; ARG_265 Pi-pi: PHE_26 |

| 6 | 3W7F | 460628 | #Squalestatin analog 25 | − 400.95 | − 14.399 | − 104.739 | − 347.532 | SER_19; ARG_45; ASN_168; ARG_171; TYR_248 | Salt Bridges: ARG_45; ARG_171; ARG_265 |

| 7 | 3W7F | 460634 | #Squalestatin analog 32 | − 682.59 | − 13.485 | − 124.578 | − 384.947 | LYS_20; ARG_45; ASP_48; GLN_165; ASN_168; ARG_265 | Salt Bridges: LYS_20; ARG_45; ARG_265 |

| 8 | 3W7F | 460638 | #Squalestatin analog 36 | − 669.88 | − 13.740 | − 125.499 | − 431.413 | SER_19; ARG_45; ASN_168; ARG_171; ARG_265 | Salt Bridges: ARG_45; ARG_171; ARG_265 |

*Standard compound

#Test compound

The positive control farnesyl thiopyrophosphate was re-docked with CrtM and we obtained a docking score (− 10.600 kcal/mol) along with the formation of three hydrogen bonds with ASN_168, ARG_171, and ARG_265 and two salt bridges with ARG_171 and ARG_265. Out of seven selected test compounds, lapaquistat acetate exhibited the lowest docking score (− 15.637 kcal/mol) and formed only one hydrogen bond with ASN_168 and one pi–pi interaction with TYR_41. On the other hand, Squalestatin analog 20 showed the second-lowest docking score (− 15.413 kcal/mol) and formed five hydrogen bonds with SER_19, ARG_45, GLN_165, ASN_168, and ARG_171; three salt bridges with ARG_45, ARG_171 and ARG_265; and one pi–pi interaction with PHE_26. However, ASN_168 was the only common hydrogen bond involved in the binding of standard and test compounds. Due to the high binding affinity values of these two compounds and the involvement of important amino acids, we proceeded with further evaluation of these 2 compounds through molecular simulations.

MD simulations for docking validation

To obtain more accurate confirmations of the protein due to the flexible nature of the amino acid residues, various thermodynamic properties and stability parameters were evaluated by molecular dynamic simulations using the Desmond module of Schrodinger’s Maestro (Nayak et al. 2021). 2D interaction of protein–ligand contacts, root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (ROG), and various intermolecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, ionic and water bridges) for the standard drug and top 2 test compounds viz., lapaquistat acetate and squalestatin analog 20 were examined concerning the initial structure through MD simulations for 100 ns time frame.

-

A.

Protein RMSD: The P-RMSD of all the complexes was calculated and the results revealed that Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate (1.271460539 Å) showed the lowest P-RMSD followed by Lapaquistat acetate (1.584458541 Å) and Squalestatin analog 20 (1.85192408 Å) signifying that these complexes were more stable than the other complexes as shown in Fig. 1Sa–c.

-

B.

Ligand RMSD: The L-RMSD for Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate (1.845926074 Å) < Lapaquistat acetate (2.018210789 Å) < Squalestatin analog 20 (2.5823037 Å) as illustrated in Fig. 1Sa–c.

-

C.

Protein RMSF: The C-alpha RMSF of all the proteins from the complexes was calculated and the results showed that Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate (0.716211267605634 Å) exhibited the lowest C-alpha RMSF followed Lapaquistat acetate (0.758704225352112 Å) and Squalestatin analog 20 (0.787260563380281 Å). Protein–ligand contacts are marked with green-colored vertical bars and can be seen in Fig. 2Sa–c.

-

D.

Ligand-RMSF: Our results showed that Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate (1.231291666 Å) exhibited the highest entropic value followed by Squalestatin analog 20 (1.15826087 Å) and Lapaquistat acetate (0.802111111 Å) as shown in Fig. 3Sa–c.

-

E.

Secondary Structure Elements: The residue % SSE plot depicts the SSE composition for each trajectory frame within a 100 ns simulation run, whereas the Residue Index plot represents each residue and its SSE assignment over time. Our results revealed that both the complexes had an average confirmation with 67.50% (Lapaquistat acetate) and 66.79% (Squalestatin analog 20) mainly consisting of alpha-helices rather than strands, loops or turns which interpret conformational changes during the simulation run as displayed in Fig. 4Sa–c.

-

F.

Radius of Gyration: Our results showed that Lapaquistat acetate was stabilized throughout the simulation run. However, Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate and Squalestatin analog-20 were slightly destabilized and did not attain stability till the end of the simulation run. The rGyr plots were illustrated in Fig. 5Sa–c.

-

G.

Protein–ligand Contacts: Our results revealed that the standard compound i.e., Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate interacted with CrtM by forming strong ionic bonds with ASP_48, ASP_52, ASN_168, ARG_171, ASP_172, GLU_175 and ASP_176; strong H bonds with ARG_45 and ASN_179; and hydrophobic interactions with TYR_41 and CYS_44. In the case of Lapaquistat acetate, it interacted with CrtM by establishing strong ionic bonds with ASP_48, ASP_52, ASN_168, and ASP_172; strong H bond with ASN_168; and hydrophobic interactions with PHE_26 and TYR_41. Similarly, Squalestatin analog 20 interacted with CrtM by forming strong ionic bonds with SER_21, ARG_171 and TYR_248; strong H bonds with SER_19, LYS_20, PHE_22, TYR_41, ARG_45, GLN_165 and TYR_248; and hydrophobic interactions with MET_15, PHE_26, ILE_40, TYR_41, VAL_137 and LEU_141. The detailed representation of all the protein–ligand contacts can be seen in Fig. 6Sa–c.

-

H.

Protein–ligand Timeline: The top panel represents the exact number of protein–ligand interactions over a 100 ns time frame. Wherein, the bottom panel characterizes residue-wise interaction with the ligand within each trajectory frame. The scale on the right side of the plot displays those amino acid residues involved in multiple contacts with the ligand by dark orange shade as displayed in Fig. 7Sa–c.

Binding free energy calculation

The calculated binding free energy of the screened compounds ranged from − 31.6291124 kcal/mol to 87.74813056 kcal/mol (Table 2). A comparison between docking energy and binding energy was performed to further validate the docking poses (Fig. 2). The MM-GBSA results illustrate that Squalestatin analog 20 showed the lowest binding free energy (− 31.6291124 kcal/mol) wherein, Squalestatin analog 36 had the highest binding free energy (87.74813056 kcal/mol). MM-GBSA scoring provides considerable correlation with experimentally determined data. Therefore, MM-GBSA results are well correlated with induced fit docking results that showed Lapaquistat acetate (− 103.744 kcal/mol) and Squalestatin analog 20 (− 114.143 kcal/mol) exhibited better binding affinities. To sum up, the MM-GBSA calculations did not match the exact order of docking energies of complexes. There was a slight change in the order of docking energy and binding energy for intermediate docking energy-holding compounds.

Table 2.

MM-GBSA binding free energy calculations (kcal/mol) of the standard and test compounds

| SI. No | PDB ID | Compound ID | Compound name | ∆G Bind | ∆G Bind coulomb | ∆G Bind covalent | ∆G Bind H-bond | ∆G Bind lipophilic | ∆G Bind Solv_GB | ∆G Bind vdw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3W7F | 657041 | *Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate | 41.35093351 | − 264.9015262 | 4.068187364 | − 1.972024881 | − 15.2449054 | 359.426185 | − 40.02498242 |

| 2 | 3W7F | 9874248 | #Lapaquistat Acetate | 26.03160285 | − 111.251167 | 5.998579441 | − 0.31449534 | − 30.04511132 | 229.3776515 | − 66.91664637 |

| 3 | 3W7F | 460617 | #Squalestatin analog 2 | 43.72861713 | − 291.5742432 | 5.772067285 | − 3.776407168 | − 19.93325006 | 395.0158787 | − 40.45544445 |

| 4 | 3W7F | 460618 | #Squalestatin analog 15 | 68.92768293 | − 332.5843704 | 8.276833257 | − 3.691859329 | − 17.63377558 | 468.6685922 | − 54.01321557 |

| 5 | 3W7F | 460623 | #Squalestatin analog 20 | − 31.6291124 | − 278.1505501 | 3.981017183 | − 5.8040562 | − 27.21508802 | 335.062705 | − 58.88939664 |

| 6 | 3W7F | 460628 | #Squalestatin analog 25 | 0.538613618 | − 266.1973454 | 4.326203927 | − 8.376411491 | − 16.92758347 | 336.8968821 | − 49.06439964 |

| 7 | 3W7F | 460634 | #Squalestatin analog 32 | 70.20593807 | − 227.8190179 | 6.322848179 | − 3.640353706 | − 16.23625344 | 362.5965543 | − 50.46958792 |

| 8 | 3W7F | 460638 | #Squalestatin analog 36 | 87.74813056 | − 317.5786729 | 6.994813555 | − 3.344115849 | − 14.22447926 | 462.3803295 | − 46.42899653 |

*Standard compound

#Test compound

Fig. 2.

Molecular docking energy (Glide energy) and prime MM-GBSA binding energy (ΔGbind) in kcal/mol of the standard and test compounds. The blue line indicates binding energy, whereas the orange line represents docking energy

Per-residue energy decomposition analysis

To understand the role of individual amino acid residues, per-residue energy decomposition analysis was performed (Gupta et al. 2018). In this methodology, the total interaction energy is sub-divided into the contributions from individual amino acid residues allowing the quantification of their interaction energy contributions. The role of individual amino acid residues is vital while designing a new drug and defining pharmacophore features and it helps identify key residues important for ligand binding. The calculation of docking and binding energies is based on protein–ligand interactions using a single pose obtained from docking, MD simulations, or MM-GBSA. However, it is important to understand that there are many systems where a complete conformational sampling may be significant to obtain a good correlation with the experiment (Thapa and Raghavachari 2019).

The residue decomposition analysis shows that there are several other amino acid residues apart from residues obtained from molecular docking and MD simulations that are essential for protein–ligand interaction and can be considered potential amino acid candidates for further studies in this domain. Some of the key residues in standard and test compounds, namely LYS_17, LYS_20, LYS_46, ARG_85, ARG_181, and ARG_265 among the highest contributing residues across the binding process through Coulombic interactions. Per-residue decomposition analysis also revealed that ARG and LYS are essential amino acid residues in the binding of lapaquistat acetate and squalestatin analog 20 into the active site of dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM). To sum up, the role of individual amino acid residues allows improved pharmacophore modeling that helps in the generation of a concise library of small molecules. The detailed results are provided in Table 1S.

Analysis of protein tunnels and ligand transport

Protein tunnels and channels are key transport pathways essential for the transport of small molecules into the active site of the protein. Protein tunnels are void pathways characterized by a single opening. They play an important role in the transport of ligands, products, solvents, and ions in and out of the binding site.

Caver Web v1.1 (https://loschmidt.chemi.muni.cz/caverweb/) was used to study and predict the trajectory and energy profile of a ligand being transported through a molecular tunnel (Marques et al. 2019). It is based on molecular docking and it can be used for the high-throughput screening of potential ligands, drugs, or lead compounds that can be transported through the biomolecular tunnels. The tunnels were calculated using a probe radius of 0.9 Å, a shell radius of 3 Å, and a shell depth of 4 Å. The protein–ligand complexes of the standard and top two complexes were used as input for the Caver Web calculations. Our results revealed that the substrates (Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate, Lapaquistat acetate, and Squalestatin analog 20) interact with vital bottleneck amino acid residues in the tunnel with 3W7F as illustrated in Fig. 8Sa–c. Bottleneck residues involved in protein–ligand contacts are marked in (aquamarine-cyan). From the suggested tunnels, the most biologically relevant tunnel involved in hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions was selected for the study of energy profiles: (i) the binding energy of the bound state (EBound), (ii) the maximum binding energy (EMax) and (iii) the binding energy at the surface (ESurface). If the values of activation energy of association (EA) are comparable for multiple tunnels, in that case, the tunnel with lower maximum binding energy (EMax) was considered. Bottleneck residues involved in protein–ligand interactions in case of Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate (Tunnel 1—HIS_18, ASP_48, ASP_52, LEU_107, VAL_111, TYR_129, VAL_133, ALA_134, GLN_165, and ASN_168); Lapaquistat acetate (Tunnel 1—HIS_18, TYR_41, ARG_45, ASP_48, ASP_49, VAL_133, GLN_165, ASN_168 and ARG_171); and Squalestatin analog 20 (Tunnel 1- PHE_22, TYR_41, ARG_45, ASP_48, VAL_133, ALA_134, LEU_164, GLN_165, ASN_168, ARG_171 and TYR_248). The bottleneck residues for the standard and test compounds in protein–ligand binding can be seen in Table 2S. The energy profile for the appropriate tunnels was performed for the standard and test compounds that were involved in ligand transport as summarized in Table 3S.

ADMET analysis

To predict the druggability of the compounds more accurately, the ADMETlab 2.0 (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) web tool was used for the ADME analysis. All the standard and test compounds were tested based on properties, such as BBB penetration, MDCK permeability, Caco-2 permeability, HERG blockers, PAINS, Lipinski rule, skin sensitization, eye corrosion, T1/2 and human intestinal absorption (HIA). However, the toxicity of all the compounds was predicted using the PreADMET tool based on the toxicity properties, such as AMES test, Carcino mouse, Acute algae toxicity, Acute daphnia toxicity, and Acute fish toxicity. After careful inspection of the compounds, it was noticed that the standard compound Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate and test compound Lapaquistat acetate fulfilled most of the ADMET properties as compared to other Squalestatin analogs. The detailed results are shown in supplementary data Table 4S.

Discussion

The dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) enzyme of S. aureus plays an essential role in staphyloxanthin biosynthesis. Staphyloxanthin, a carotenoid pigment regulates the anti-oxidant level in S. aureus which is essential for its survival in adverse conditions. It is evident from previous studies that cholesterol-lowering agents are powerful inhibitors of CrtM which provides a basis for rational drug design methods against S. aureus. In the present investigation, molecular docking studies were performed using the Induced fit docking (IFD) module of Schrodinger’s Maestro to find the binding site of human SQS inhibitors, such as Lapaquistat acetate and Squalestatin analogs, within the active site of CrtM of S. aureus to study molecular interaction among them. The IFD module is based on Glide and the Refinement module in Prime, which accurately predicts ligand-binding modes and inter-connected structural changes in the receptor. IFD is a process in which a receptor is allowed to move to bind to the ligand optimally. The docking scores of all the ligands with the protein ranged between − 15.637 kcal/mol and − 13.202 kcal/mol, which is considerably better than the standard drug complex i.e., − 10.600 kcal/mol. Further, important amino acid residues involved in protein–ligand interactions were also noted as mentioned in Table 1.

Structure-based virtual screening may produce false positives due to rigid body consideration of target protein and lack of solvation effects (Singh et al. 2022). Therefore, docking results were further validated through MD simulations by analyzing various thermodynamic properties. The P-RMSD values must be within the range of 1–4 Å. The lower RMSD values indicate that the protein structure is more stable and has equilibrated (Ahmad et al. 2022). The ligand RMSD values should be less than the protein RMSD which indicates that the ligand is stable concerning the protein and its active site. On the other hand, if ligand RMSD values are higher than the RMSD values of the protein, there is a strong possibility that the ligand has moved away from its initial binding site (Fig. 1Sa–c). Based on PL-RMSD values, we can conclude that Lapaquistat acetate and Squalestatin analog 20 showed better results as compared to other test compounds. Protein RMSF represents the local changes along the protein chain. Generally, the tails (N- and C-terminals) fluctuate the most as compared to other parts of the protein. However, the secondary structure elements (alpha-helices and beta-strands) are rigid as compared to the loop regions, thus fluctuate less (Fig. 2Sa–c). Ligand-RMSF signifies the ligand’s atom-wise fluctuations, corresponding to its 2D structure. The L-RMSF may give you a glimpse into the binding of ligand fragments with the protein and their entropic role in the binding. Values up to 2 Å are an acceptable range (Fig. 3Sa–c).

Secondary structure elements (SSE) of a protein, such as alpha-helices and beta-strands, are monitored throughout the simulation run (Fig. 4Sa–c). The radius of Gyration (rGyr) measures the ‘extendedness’ of a ligand and is equivalent to its principal moment of inertia (Fig. 5Sa–c). Protein–ligand interactions can be monitored throughout the simulation run. There are four types of P–L interactions (or ‘contacts’) viz., Hydrogen bonds, Hydrophobic, Ionic, and Water Bridges (Fig. 6Sa–c). The timeline representation of protein–ligand contacts (H-bonds, hydrophobic, Ionic, and Water bridges) has been analyzed in detail (Fig. 7Sa–c). The RMSD and RMSF values indicated that top test compounds i.e., Lapaquistat acetate and Squalestatin analog 20 were relatively stable, and no fluctuations were observed. After careful inspection of the thermodynamic properties, it was found that test compounds Lapaquistat acetate and Squalestatin analog 20 were much better than the other test compounds. Based on different molecular interactions, such as ionic bonds, H bond interactions, and hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions, the most important amino acid residues were ARG_45, ASP_48, ASP_52, ASN_168, and ASP_172.

To further validate the simulation studies, the binding free energy between the protein and screened ligands was calculated through Prime MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) (Schrodinger Release 2022-4). The MM-GBSA results ranged from -31.6291124 kcal/mol to 87.7481305 kcal/mol. dGbind values of the test compounds obtained from residue decomposition ranged between − 39.05 kcal/mol and − 54.13 kcal/mol which was much better than the reference molecule i.e., − 33.15 kcal/mol. Out of seven test compounds, Squalestatin analog 20 showed the lowest binding free energy (− 31.6291124 kcal/mol), whereas Squalestatin analog 36 has the highest binding free energy (87.74813056 kcal/mol).

Protein tunnels are vital substructures mainly found in globular proteins with catalytic activity. They play various important roles in ligand transport, products, co-factors, water molecules, and/ or inhibitors. After careful inspection, we found that standard and test compounds interacted with various bottleneck residues in the tunnel (Table 2S). The output of Caver Web consists of a detailed report containing various parameters such as Tunnel—selected protein tunnel; Substrate—name of the substrate; Direction—direction of the CaverDock calculation; EBound: binding energy of the bound state; EMax: the maximum binding energy; ESurface: the binding energy at the surface; EA: activation energy of association; EMax—EBound: for products; EMax—ESurface: for reactants; ΔEBS: difference of the binding energies of the substrate in the active site and at the surface (Pinto et al. 2022). Caver Web automatically calculates EA and ΔEBS based on EBound, EMax, and ESurface for the selected tunnels. Lower energy values of EMax and EA signify well-bound protein–ligand complexes (Table 3S). In our results, Farnesyl thiopyrophosphate, Lapaquistat acetate, and Squalestatin analog 20 exhibit only one tunnel for the transport of ligands. The tunnel constitutes all the bottleneck residues that are important to bind with the ligand for further transport across tunnels to carry out several biological functions. A detailed summary of the energy profiles for the selected protein–ligand complexes can be seen in Fig. 9Sa–c.

In addition, physicochemical profiling of a drug molecule is one of the major worries and most of the drug candidates fail due to poor physicochemical properties. In silico ADMET analyses were performed to check the drug-likeliness properties of the standard and test compounds. It was found that the test compound Lapaquistat acetate fulfilled most of the druggable-like properties suggesting that this molecule can be absorbed orally, distributed well in the body, and could be considered in further stages of the drug design process. Although, all other analogs passed in silico ADMET properties. Lapaquistat acetate and Squalestatin analog 20 were selected based on showing favorable scores, binding affinity, and stability among all the studies that we performed in our study.

Conclusion

The current research focuses on identifying possible therapeutic inhibitors of dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) which is a key enzyme in staphyloxanthin synthesis. The pathway of dehydrosqualene synthesis is similar to the cholesterol synthesis pathway in humans that provides a basis for rational drug design for use against S. aureus. An in silico approach including molecular docking, MD simulation, and free energy calculation through MM-GBSA was employed to recognize potential inhibitors for CrtM of S. aureus to examine various interactions, important amino acid residues, and specific binding regions of the inhibitors into the active site of the protein. The ionic and hydrogen bonds produced within the active site of CrtM are considered key interactions indicating strong binding of the inhibitors. In addition, hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions also play a vital role in the binding process. Furthermore, several amino acid residues (SER_19, LYS_20, ARG_45, ASP_48, GLN_165, ASN_168, ARG_171, ARG_265, and TYR_248) are essential for the molecules for binding into the active site. The thermodynamic parameters, such as RMSD, RMSF, and rGyr, were studied to assess the stability of the protein–ligand complex, fluctuations between the residues and target protein, compactness of the protein complexes over the 100 ns simulation run. To conclude, Lapaquistat acetate and Squalestatin analog 20 showed the best binding affinity among all other test compounds due to their strong binding within the active site. It is expected that these findings pave the way for the use of Squalestatin analogs as potential inhibitors against CrtM. The study would help in the development of virulence factor-based therapy against S. aureus.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

SR and IB conceptualized and designed the research study; IB and VP performed data curation and experiments. IB and VP performed in-silico data analysis; IB and SR wrote the manuscript; VPR and SR critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors hereby declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

There is no involvement of any potential conflicts of interest, funding, or research involving human participation and/or animals.

References

- Ahmad B, Saeed A, Castrosanto MA, et al. Identification of natural marine compounds as potential inhibitors of CDK2 using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2135594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aribisala JO, Sabiu S. Cheminformatics identification of phenolics as modulators of penicillin-binding protein 2a of Staphylococcus aureus: a structure–activity-relationship-based study. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1818. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14091818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banu S, Bollu R, Naseema M, et al. A novel templates of piperazinyl-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylates: synthesis, anti-microbial evaluation and molecular docking studies. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:1166–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Omar MT. Data analysis of molecular dynamics simulation trajectories of β-sitosterol, sonidegib and cholesterol in smoothened protein with the CHARMM36 force field. Data Brief. 2020;33:106350. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary MI, Shaikh M, Tul-Wahab A, Ur-Rahman A. In silico identification of potential inhibitors of key SARS-CoV-2 3CL hydrolase (Mpro) via molecular docking, MMGBSA predictive binding energy calculations, and molecular dynamics simulation. PLOS ONE. 2020;15:e0235030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal V, Dhankhar P, Singh V, et al. Structure-based identification of potential drugs against FmtA of Staphylococcus aureus: virtual screening, molecular dynamics, MM-GBSA, and QM/MM. Protein J. 2021;40:148–165. doi: 10.1007/s10930-020-09953-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2021. Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools, Schrödinger, New York, NY, 2021

- Elmesseri RA, Saleh SE, Elsherif HM, et al. Staphyloxanthin as a potential novel target for deciphering promising anti-Staphylococcus aureus agents. Antibiot Basel Switz. 2022;11:298. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Davies J, Kao RYT. Dehydrosqualene desaturase as a novel target for anti-virulence therapy against Staphylococcus aureus. mBio. 2017;8:e01224–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01224-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Chaudhary N, Aparoy P. MM-PBSA and per-residue decomposition energy studies on 7-Phenyl-imidazoquinolin-4(5H)-one derivatives: Identification of crucial site points at microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) active site. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;119:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain A, Ahmad A, Khan SA, et al. Synthesis, molecular properties, toxicity and biological evaluation of some new substituted imidazolidine derivatives in search of potent anti-inflammatory agents. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlon AK, Roy S, Sharma A. Molecular docking studies to map the binding site of squalene synthase inhibitors on dehydrosqualene synthase of Staphylococcus Aureus. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2010;28:201–210. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2010.10507353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Rathi R, Pathak SR, Dalal V. Structural-based virtual screening and identification of novel potent antimicrobial compounds against YsxC of Staphylococcus aureus. J Mol Struct. 2022;1255:132476. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Lee IH, Kim HJ, et al. The PreADME approach: web-based program for rapid prediction of physico-chemical, drug absorption and drug-like properties, EuroQSAR 2002 designing drugs and crop protectants: processes, problems and solutions. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 418–420. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C-I, Liu GY, Song Y, et al. A cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor blocks Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Science. 2008;319:1391–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1153018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques SM, Bednar D, Damborsky J. Computational study of protein-ligand unbinding for enzyme engineering. Front Chem. 2019;6:650. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metwaly AM, Elwan A, El-Attar A-AMM, et al. Structure-based virtual screening, docking, ADMET, molecular dynamics, and MM-PBSA calculations for the discovery of potential natural SARS-CoV-2 helicase inhibitors from the Traditional Chinese Medicine. J Chem. 2022;2022:1–23. doi: 10.1155/2022/7270094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Musil M, Jezik A, Jankujova M, et al. Fully automated virtual screening pipeline of FDA-approved drugs using Caver Web. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:6512–6518. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak C, Singh SK. In silico identification of natural product inhibitors against Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct4) to impede the mechanism of glioma stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0255803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto GP, Hendrikse NM, Stourac J, et al. Virtual screening of potential anticancer drugs based on microbial products. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86:1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger Release 2022–4: LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2022. https://www.schrodinger.com/

- Schrödinger Release 2022–4: Maestro, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2022. https://www.schrodinger.com/

- Schrödinger Release 2022–4: Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2022. https://www.schrodinger.com/

- Singh G, Soni H, Tandon S, et al. Identification of natural DHFR inhibitors in MRSA strains: structure-based drug design study. Results Chem. 2022;4:100292. doi: 10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stourac J, Vavra O, Kokkonen P, et al. Caver Web 1.0: identification of tunnels and channels in proteins and analysis of ligand transport. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W414–W422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Rice KC. Measurement of Staphylococcus aureus pigmentation by methanol extraction. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2021;2341:1–7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1550-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa B, Raghavachari K. Energy decomposition analysis of protein-ligand interactions using molecules-in-molecules fragmentation-based method. J Chem Inf Model. 2019;59:3474–3484. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong G, Wu Z, Yi J, et al. ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W5–W14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.