Abstract

Thyroid ultrasound is a widely used diagnostic technique for thyroid nodules in clinical practice. However, due to the characteristics of ultrasonic imaging, such as low image contrast, high noise levels, and heterogeneous features, detecting and identifying nodules remains challenging. In addition, high-quality labeled medical imaging datasets are rare, and thyroid ultrasound images are no exception, posing a significant challenge for machine learning applications in medical image analysis. In this study, we propose a Dual-branch Attention Learning (DBAL) convolutional neural network framework to enhance thyroid nodule detection by capturing contextual information. Leveraging jigsaw puzzles as a pretext task during network training, we improve the network’s generalization ability with limited data. Our framework effectively captures intrinsic features in a global-to-local manner. Experimental results involve self-supervised pre-training on unlabeled ultrasound images and fine-tuning using 1216 clinical ultrasound images from a collaborating hospital. DBAL achieves accurate discrimination of thyroid nodules, with a 88.5% correct diagnosis rate for malignant and benign nodules and a 93.7% area under the ROC curve. This novel approach demonstrates promising potential in clinical applications for its accuracy and efficiency.

Keywords: Self-supervised learning, Thyroid nodule, Ultrasonography, Attention

Introduction

Thyroid cancer represents the most prevalent form of endocrine malignancy [1]. Improving the identification and detection of thyroid nodules has become a crucial strategy to prevent this disease. However, evaluating thyroid nodules poses a significant challenge in the clinical setting. Currently, cervical imaging techniques such as ultrasound constitute the primary means of identifying or detecting thyroid nodules [2]. Ultrasound imaging has long been used as a screening method for the clinical diagnosis of thyroid nodules. The radiologist also proposed a guideline for thyroid nodule characteristics based on ultrasound images [3], and identified some ultrasound characteristics of thyroid nodules as indicative of malignancy, including low echo, no halo, microcalcification, solid component, flow within the nodule, and high-width shape [4]. Based on these features, radiologists have also devised a specialized thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS) for classifying thyroid nodules and stratifying their risk of malignancy for use by radiologists [5]. However, evaluating thyroid nodules using TI-RADS is time-consuming and limited by the imaging mechanism of ultrasonic images. Medical ultrasound images are characterized by low contrast and significant noise interference, as shown in Fig. 1. As a result, ultrasound diagnosis often depends on the experience of radiologists [6]. Inexperienced doctors may not be able to accurately interpret ultrasonic characteristics, leading to a high rate of misdiagnosis. Misdiagnosis can result in unnecessary biopsies, causing undue stress and anxiety.

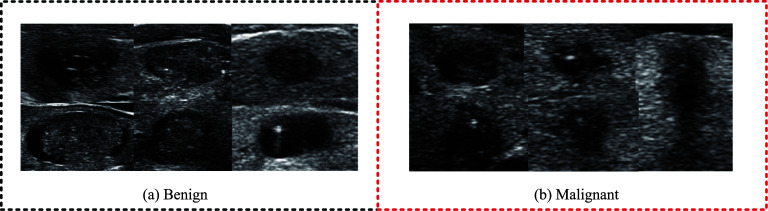

Fig. 1.

Thyroid nodules: a Benign nodules; b Malignant nodules

In order to effectively utilize the diagnostic experience of experienced radiologists, a computer-assisted diagnostic system for objectively and automatically classifying thyroid nodules has emerged. However, there are many limitations in building a successful computer-aided diagnostic system. For example, the appearance of the thyroid gland is often influenced by various factors such as internal content, shape, and echo. Therefore, the shape characteristics are significantly different, and the shape and layout of different nodules are also different. Traditional auxiliary diagnostic methods usually involve manually extracting features from ultrasound images, and then using classifiers to classify these features [7]. Acharya et al. proposed a new Gabor-transform-based automatic classification system for high-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) of thyroid nodules [8]. Raghavendra et al. combined spatial gray-level dependent features (SGLDF) with fractal texture to explain the internal structure of benign and malignant thyroid lesions. In traditional systems, only features with a given height difference can solve the recognition problem well. However, for thyroid nodules, the high variability of ultrasound images makes it difficult to effectively differentiate between benign and malignant nodules [9]. Therefore, it is more critical to design and choose the most prominent features. In addition, most existing classifiers tend to overfit the training dataset, as features designed locally at a single scale and a single region are not sufficient to encode key information to identify different types of nodules.

With the advancement of machine learning and artificial intelligence, an increasing number of deep learning methods have been employed in the domain of intelligent auxiliary diagnosis. Among the image processing techniques, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [10] can greatly improve the classification and detection performance of natural images without additional manual feature extraction, and their excellent raw image processing capabilities also provide strong support for medical image analysis tasks. Some studies have proposed using convolutional neural networks to automatically extract ultrasound features and diagnose malignant thyroid tumors. For example, Song et al. [11] introduced a multi-task cascade convolutional neural network (MC-CNN) framework to leverage contextual information of thyroid nodules. This method captures the intrinsic features of different scales from a global to a local perspective to identify multi-scale recognition information in the complex structure of the thyroid. However, the detection and identification of small nodules remains challenging, and there is a lack of high-quality training data. Liu et al. [12] proposed a deep learning model that combines S-Mask R-CNN and Inception-v3 for ultrasound image-assisted diagnosis of prostate cancer. They used cubic linear interpolation algorithm instead of bilinear interpolation algorithm to improve segmentation accuracy and model detection effect, and indicated that they also faced the problem of insufficient data. Liu et al. [13] introduced prior knowledge and designed a network to automatically detect and classify nodules in ultrasound images under the guidance of prior knowledge for specific tasks. However, there are also problems such as imbalanced data categories and rough annotations. Guo et al. [14] proposed an effective method for segmentation of thyroid ultrasound images based on n-cell graph cutting, which is used to identify thyroid nodules that meet specific criteria. Experienced radiologists manually evaluate and select results. Experiments show that this method can accurately find the desired rendered image with 100% accuracy. This method can help radiologists diagnose thyroid disease using qualified rendered images. Although convolutional neural networks have achieved certain success in the field of medical image analysis, they rely on a large amount of labeled data to learn relevant features. In the field of medical images, on the one hand, it is very expensive and time-consuming to construct a sufficiently large labeled high-quality medical dataset, and on the other hand, unlike natural scene image data, which can be annotated by amateurs, medical datasets require experts with domain knowledge to complete the annotation process, and when dealing with some serious diseases, the annotation process also involves patient privacy issues [15]. These factors make the scarcity of training data in terms of annotation and quantity a major obstacle to the application of machine learning in the medical field [16].

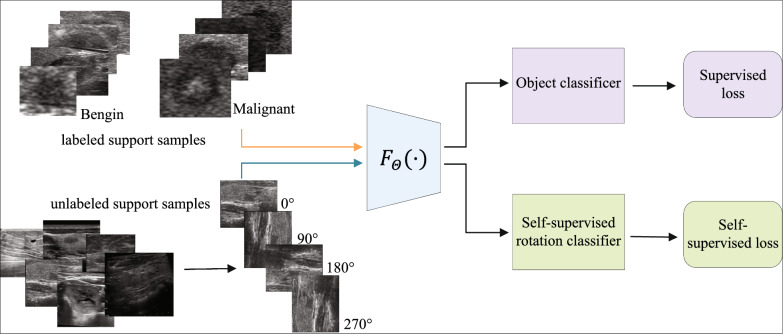

Self-supervised learning is one of the methods to solve the problem of insufficient annotated datasets. It learns feature extractors from unlabeled data. The model generates supervision signals, learns semantic features without manual annotation [17], and applies the learned features to subsequent learning tasks (Show as Fig. 2). Even if the amount of annotated data in subsequent tasks is very limited, good results can be obtained. Zhang and Wang [18] introduced the slice ordering task, which represents three-dimensional medical images such as CT and MRI scans as a set of continuous two-dimensional slices, and uses this property as an auxiliary supervision signal for learning. The author treats the task of sorting slices as a binary sorting problem, receiving two consecutive slices and predicting whether their spatial order is lower or higher. Bai et al. [19] proposed a task of predicting anatomical locations from cardiac MRI scans for segmentation. MRI scans of the heart can provide multiple views of the heart, and different anatomical regions of the heart can be represented using these views. Therefore, the author defines a set of anatomical locations of the view as a closed box and forces the network to predict these anatomical locations. Taleb et al. [20] proposed another work inspired by jigsaw puzzle solutions [21], which utilizes multiple imaging modalities, such as simultaneous T1 and T2 scans, known as multi-modal patchwork, to solve the patchwork classification task by learning to arrange tasks. Self-supervised learning method does not require manual annotation, which makes the learning method more robust and is considered an effective solution to solve the scarcity of annotated medical data.

Fig. 2.

Framework of self supervised learning

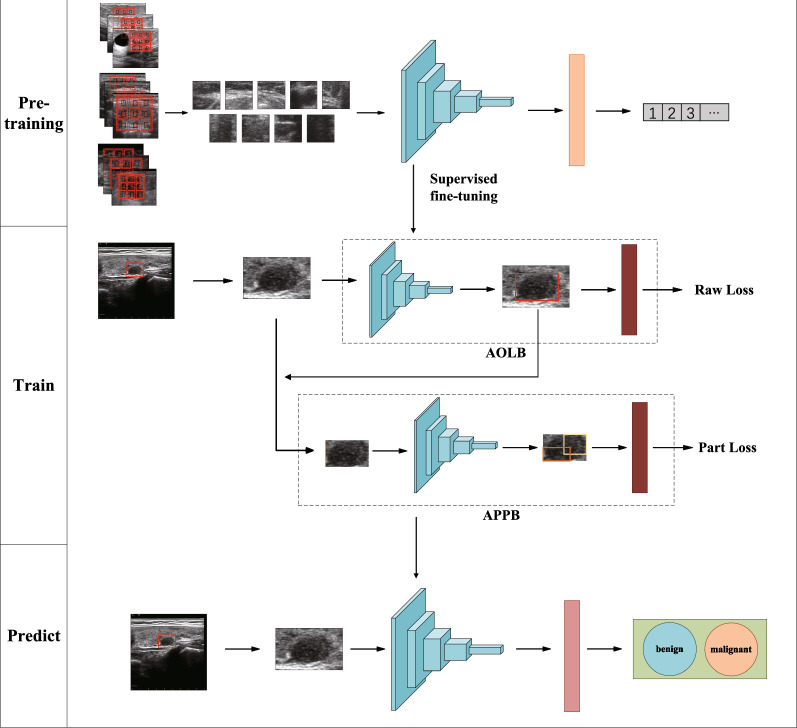

In this work, inspired by the Jigsaw Puzzles [21], we construct a convolutional neural network (CNN) pre-training task called thyroid nodule puzzle task to address the scarcity of high-quality annotation data. We use unlabeled data sets for training and learning, so that the network model can learn to extract relevant texture features of thyroid ultrasound images. Then, in order to solve the problem of thyroid nodule classification and improve the robustness of small data set models, the task is fine-tuned and transfer learning is used to transfer the feature extraction network to the main task. In the main task, we propose a new deep learning framework: Dual Branch Attention Learning (DBAL), which will analyze the characteristics of thyroid ultrasound and focus on specific domain knowledge and radiologists’ experience for automatic classification of thyroid nodules in ultrasound images. The learning framework we propose mainly includes two main branches. The first branch is the Attention Object Localization Branch (AOLB), which is a basic branch that extracts semantic features from the input, mainly extracting the overall semantic features of thyroid nodules, such as aspect ratio of the outline; The other branch is the attention site extraction branch (APPB), which mainly analyzes the consolidation of cysts within the nodule to introduce knowledge of TIRads and guide identification. The experimental results show that this method is effective and has high accuracy for the diagnosis of thyroid nodules. The overall network framework is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Architecture of our self-supervised learning framework. It consists of two stages. (1) Pre-training stage: Feature extraction of unsupervised learning; (2) Training stage: Fine tuning training with label data; these trainings are combined to obtain the model parameters of the final prediction stage

Method

Self-supervised pre-training network for jigsaw puzzles

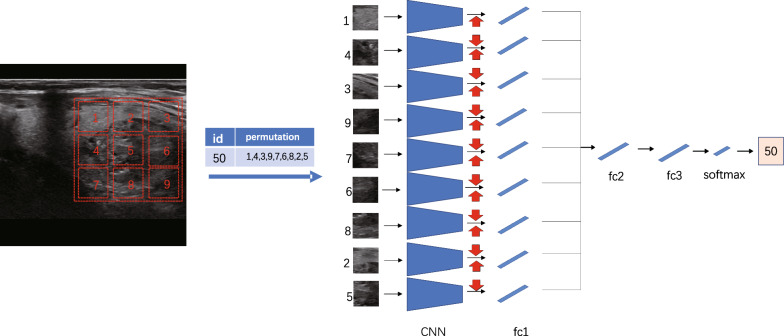

Motivated by the concept of Jigsaw Puzzles, we developed a pre-training network with the primary objective of solving these puzzles. Jigsaw puzzles serve as pretext tasks that promote the network’s ability to discern textures of individual puzzle pieces and their statistically relevant relationships, facilitating the extraction of high-level primitives [21]. The task of solving jigsaw puzzles serves as the primary objective in our self-supervised learning approach, allowing us to better extract texture features specific to thyroid nodules, which are crucial for their identification. The network architecture we employed is illustrated in Fig. 4, featuring a context-free structure. Each line guides the first fully connected layer, which utilizes the ResNet50 [22] structure with shared weights for feature extraction. The output of the first fully connected layer, denoted as fc1, extracts the features for each batch and is connected to the subsequent fully connected layer, fc2. All layers in a given row share the same weights up to and including fc1, as depicted in the figure that showcases the process of puzzle generation and solution. Considering the distinct imaging mechanisms between natural images and ultrasound images, we aimed to leverage unsupervised training using ultrasound images, encompassing not only thyroid but also breast and liver images. This approach enables us to identify and extract relevant ultrasonic texture information in the early stages. Our dataset comprises an open dataset sourced online (lacking pathological results) and a portion of an unannotated dataset from our cooperative hospital, which will be further detailed in the subsequent section. We randomly selected a 225225 pixel window from the unlabeled ultrasound image (indicated by the red dotted box) and divided it into a 33 grid. Subsequently, we randomly selected a 6464 pixel tile from each 7575 pixel cell. The nine tiles were then rearranged using randomly selected permutations from a preconfigured set, forming the input for the context-free network. The task at hand is to predict the index of the selected permutation. For the transfer learning experiment, we transferred the trained weights from the ResNet50 model to the downstream task of thyroid discriminant classification.

Fig. 4.

Network frame diagram of jigsaw task

The output of the puzzle task can be viewed as the spatial arrangement of the object part (or scene part) in the partial-based model of the conditional probability density function, i.e. Eq. 1

| 1 |

Where S is the guide of each patch, is the appearance of part i of the object, are intermediate features. Our goal is to train the puzzle network so that the feature has semantic properties and can identify the relative positions between each patch component. In order to avoid that when the network learns to associate each appearance with an absolute location, the feature will have no semantic meaning, but only information about any 2D location. We write y guide S as a list of tiled positions S = ,,,...,. So in this case, the condition can be decomposed into independent terms. As shown in Eq. 2

| 2 |

Where each map position is entirely by the corresponding feature .

To train the network, a shuffled image with nine patches in a random arrangement is fed as input. However, as there are 9! = 362,880 possible permutations for 9 patches, we limit the solution space by using a predefined set of permutations, each with a specific index. The goal of the architecture is to produce a probability vector on the predefined set of metrics, maximizing the probability of input permutations.

Dual-branch attention learning network

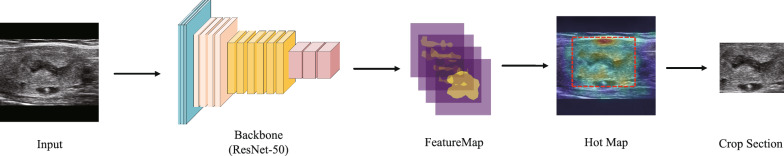

Taking inspiration from deep learning and the TI-RADS score [5], this paper introduces a multi-branch classification network that incorporates attention mechanisms. The method primarily focuses on analyzing and attending to the morphological characteristics and boundary features outlined in the TI-RADS score, as well as the specific characteristics of cyst consolidation and calcification within nodules. For instance, cystic nodules, which are mostly benign, tend to have a height-to-width ratio greater than 1, as they can easily penetrate the capsule [23]. Moreover, empirical knowledge suggests that the internal and external echo differences between benign and malignant nodules can reflect distinct modes of cell proliferation. Malignant nodules tend to exhibit rapid growth, resulting in blurred and irregular boundaries [24]. Hence, during the process of feature extraction and nodule discrimination, emphasis is placed on morphology, boundary, and contextual features. The network structure is depicted in Fig. 5. For the convenience of classification tasks, a weakly supervised localization sub network was trained to locate key parts in the image, which are usually the areas with obvious features in the image, namely the nodules. This sub network is shown by the green branch in Fig. 5. Then, for the captured key areas, in order to further obtain their fine-grained features, the captured parts are inputted into the network for feature extraction. At this time, multiple sub regions with obvious features within the captured parts can be extracted, and the sub regions can be classified to achieve fine-grained recognition and classification. This process is shown as the black branch in Fig. 5. To avoid the additional cost of manual location annotations, attention mechanisms is employed for coarse nodule recognition. Therefore, apart from annotations for benign and malignant nodules, no other information is needed.

Fig. 5.

Two-branch network structure proposed in this paper: the green branch is the original branch and the black branch is the target branch. The red dotted box is the thick location box under the attention mechanism. The same color Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Fully Connection (FC) layers represent parameter sharing. Both branches use cross entropy loss as classification loss

Attention object location branch (AOLB)

The proposed method draws inspiration from Selective Convolutional Descriptor Aggregation (SCDA) [25], which employs a pre-trained model for image feature extraction in a new granularity image retrieval task. To improve the location accuracy of SCDA, several measures were taken. Specifically, the process of generating target position coordinates was described by processing CNN feature maps, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Attention object location branch (AOLB)

The Attention Object Location Module aggregates feature mappings in the channel dimension to obtain activation mappings, from which boundary frames are obtained. Specifically, we denote the feature graph of the C channel with size HW as , which corresponds to the last convolution layer of the input image X (as shown in Eq. 3). Here, represents the i-th feature mapping of the corresponding channel.

| 3 |

Activation diagram A can be obtained by aggregation of feature diagram f. We can simply visualize the location concerned by the deep neural network for recognition, and accurately locate the target region starting from A. As shown in type 2, as a mean. As shown in Eq. 4

| 4 |

Using as a threshold to determine whether the location of element in is part of the object, (x, y) is H W activation mapping of a particular location. Then, according to Eq. 3, a rough mask mapping Mcon_5c is obtained from Conu_5c, the last convolution layer of ResNet-50 [22]. As shown in Eq. 5

| 5 |

Attention part proposal branch (APPB)

While AOLB is capable of achieving localization accuracy, sometimes it may capture part of the nodule as a positioning result, which means that the overall image does not have features that are clearly distinguishable and sufficiently classified. In order to solve this problem, we introduced APPB to enhance the robustness of the model, extract features based on the details of local images, and further classify them. This section describes our approach. Through examining the Hot Map generated by the activation map, we noticed that regions with high activation values usually correspond to the locations of key sites, such as the upper right area of the nodule in our example. We adapted the sliding window method commonly used in object detection to identify informative regions within the image. To reduce the computational complexity, we employed the traditional sliding window method and a full convolutional network, as demonstrated in Overfeat [26], to obtain the feature mappings of different windows from the feature mapping output of the previous branch. We then aggregated the activation mappings AW of each window in the channel dimension and computed their activation mean using the Eq. 6.

| 6 |

The height and width of the window feature graph are denoted by ,, respectively. To identify the windows with the most informative parts, we sort the T-values of all windows, as depicted in Fig. 7. However, selecting the first few windows directly is not optimal, since they are typically adjacent to the largest window and contain similar parts. Instead, we aim to select a diverse set of parts. To achieve this, we utilize non-maximum suppression (NMS) to choose a fixed number of windows as part images of different scales while reducing regional redundancy. By examining the output of the module, as shown in Fig. 5, we observe that our method identifies ordered parts with varying degrees of importance. In Fig. 7, the APPB Module, we use yellow, red, blue, and purple to represent the order of the window.

Fig. 7.

Attention part proposal branch (APPB)

Loss function

To enable effective and comprehensive learning of the images obtained through AOLB and APAM, we devised a two-branch network structure comprising a raw branch and a part branch, as illustrated in Fig. 5, during the training phase. The two branches share a CNN layer for feature extraction and an FC layer for classification. To facilitate learning, both branches utilize cross-entropy losses as classification losses, as given by the following Eqs. 7 and 8:

| 7 |

| 8 |

Let c denote the ground truth tag of the input image, represent the class probabilities of the output of the last softmax layer of both the original branch and the target branch, and denote the output of the softmax layer of the partial branch corresponding to the n-th part image, where n is the number of partial images. We define the total loss as a combination of the cross-entropy losses of each branch, taking into account prior medical knowledge, as shown in Eq. 9.

| 9 |

is the hyperparameter.

Dataset

Dataset introduction

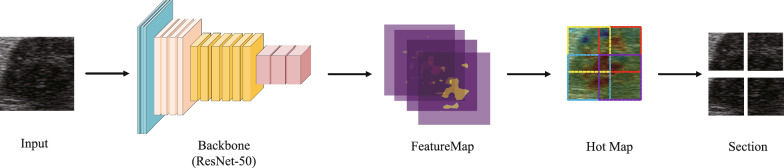

Our dataset, labeled as dataset A, was collected from Panyu Central Hospital in Guangzhou and is crucial for training our deep learning model. The dataset was annotated by experienced physicians at the hospital over a span of one year, using pathological validation as the basis. The labeling process involved identifying thyroid nodules and assigning boundary boxes to them, along with classifying them as benign or malignant. Dataset A comprises a total of 607 patients, with 258 cases labeled as benign and 349 cases labeled as malignant. This results in a total of 1214 images in the dataset. Each patient in the dataset has six ultrasound images captured using Mylab series ultrasound instruments manufactured by Esaote, an Italian company, or ultrasound instruments produced by GE Medical Group. These images include both transverse and longitudinal sections of the thyroid. Additionally, color ultrasound and elastic imaging were performed, but only the thyroid ultrasound data from standard sections were utilized for our study. The images obtained from the instruments are in the form of three-channel BMP images, with resolutions of 600800 and 12801024 pixels. Show as Fig. 8. Among the six images per patient, four of them serve as auxiliary positioning data. These images are accompanied by biopsy results and a marked box indicating the location of the nodules. By utilizing the marked boxes, we can accurately extract the corresponding nodule regions from these images. This portion of the dataset is further divided into five subsets for training and model validation purposes.

Fig. 8.

Self-collected data and its labels

Self-collected dataset B was obtained from the same hospital as dataset A, and it was collected in the early stages of the project to facilitate self-supervised pre-training. However, due to the lack of experience in data collection, the section data for patients was incomplete, and the data was not annotated. Dataset B consists of 1198 thyroid ultrasound images.

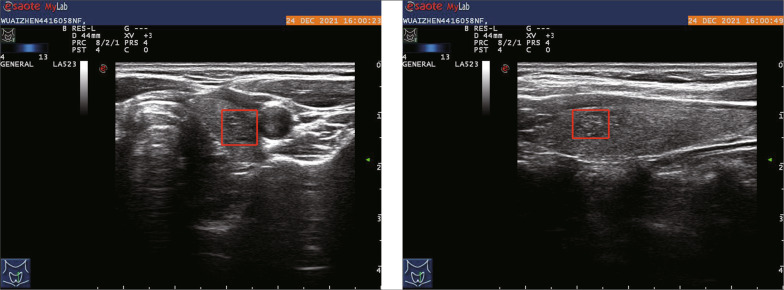

For public datasets, we utilized two ultrasound datasets: BUSI [27], which is a widely used breast cancer ultrasound dataset [28], and DDTI [4], which is a thyroid ultrasound dataset used for segmentation tasks, as shown in Fig. 9. Since there were no pathological results provided in these datasets, we used them for the puzzle pretext task. The aim of the pre-training phase was to enable the model to extract texture features related to ultrasound, and thus, the accuracy of the classification results during pre-training was not analyzed extensively.

Fig. 9.

Dataset for self-supervised pre-training

Dataset pretreatment

In our experiment, we applied appropriate data augmentation techniques to the annotated dataset to preserve the classification characteristics of the thyroid gland, its aspect ratio information, and emphasize the nodule boundary information. Unlike previous studies that employed the basic sampling method of RandomCrop, we selected image crops based on the location tag to avoid missing objects and reduce false positives. We randomly expanded the cropped edge by 20% to retain background information and facilitate feature extraction by the network’s first branch. Additionally, we randomly shifted the cropped position by 10% while expanding the length-width by 20% to maintain the length-width ratio. To ensure consistency, we filled the image with 0 using the long edge as the benchmark before interpolation, which was done using cubic linear interpolation to control the input image size to 416416.

Moreover, to enhance the texture features of ultrasonic nodules during the puzzle pretext task, we applied histogram equalization to the preprocessed images and randomly rotated them. These techniques helped to improve the model’s ability to extract texture features from the images, which is crucial in ultrasound image analysis.

Experiment

In the experiment, we first used transfer learning to initialize the pre-training weights of the self supervised learning network, and then used unlabeled dataset B and public dataset for self supervised learning as pre-training. Then, after fine-tuning the pre trained model, we moved it to the supervised learning section. We use labeled dataset A for supervised training and evaluate some existing models to demonstrate the performance of the proposed model through comparison. Finally, we conducted ablation experiments on the proposed method to examine the effectiveness of the two branches separately.

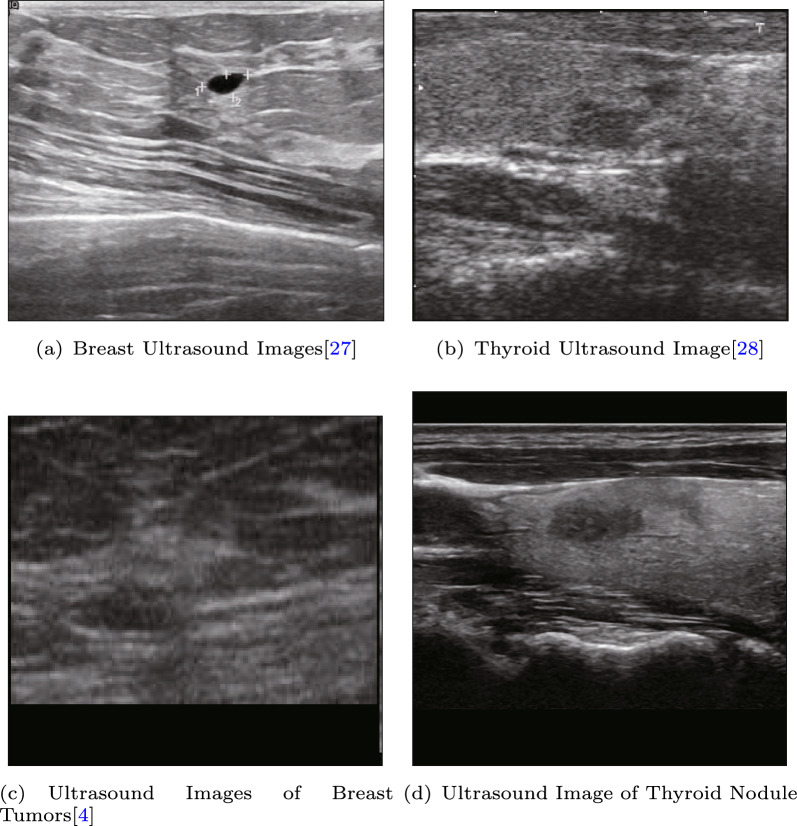

Self-supervised transfer learning experiment

We evaluated the efficacy of our proposed self-supervised pre-training approach on our self-collected dataset B and an open dataset. After completing the self-supervised learning task, we used the convolutional layer parameters of the ResNet50 model, initialized with CFN weights, to conduct subsequent supervised training. We analyzed the performance of the network before and after self-supervision and observed an improvement of 2.1% in accuracy. In the unsupervised pretext task, our focus was on training the network to learn texture information related to ultrasonic images, without concerning about the classification performance. Therefore, the pretext task was designed to train for 100 epochs. The weights obtained from the pretext task were then transferred to a supervised fine-grained classification task, and the results are presented in Table 1. In our experiments, we found that self-supervised pre-training was effective in detecting previously misclassified samples, as indicated by the heatmap outputs shown in Fig. 10. The attention of the model was shifted from being dispersed to being focused mainly on the nodules, which reflects the improvement in the model’s feature extraction capability through self-supervised pre-training.

Table 1.

Compares the results before and after pre-training using an unlabeled dataset B and C

| Backbone | ACC | AUC | sen | spec | f1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBAL-without unsuspected | 0.864 | 0.901 | 0.870 | 0.821 | 0.870 |

| Find-tune DBAL | 0.885 | 0.937 | 0.915 | 0.845 | 0.902 |

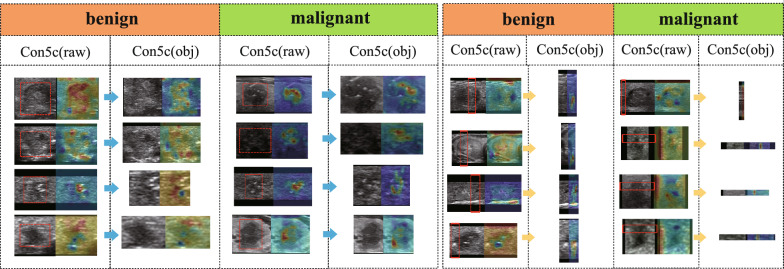

Fig. 10.

Feature distribution in the last Conu_5c convolution layer of AOLB after pre-training using an unlabeled public dataset

Supervised learning experiment

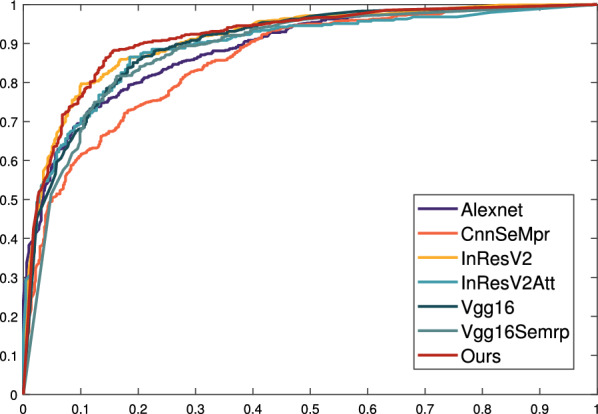

We use self collected dataset A for supervised learning in the dual branch model introduced earlier. Similarly, we evaluated the performance of learning representations using dataset A on different network benchmarks (Table 2), with all data subjected to a 50 fold cross validation. We compared our model with a model based on the classic Alexnet network [29]. Next, we also compared our thyroid classification network with the network architecture proposed by others, such as Guo X’s network with added attention mechanism [30], VGG16 network [31], VGG16SeMpr network with attention module, InResNetV2 [32] and its variant network InResNet [33]. We found that the larger the network structure, the better the classification effect. Our network structure performs better than other network structures, with an accuracy of 86.4%, as shown in Table 2. In addition, we plotted the corresponding ROC curve, as shown in Fig. 11.

Table 2.

Comparison of the effects of each network on dataset A

| Backbone | ACC | AUC | sen | spec | f1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexnet [29] | 0.799 | 0.888 | 0.838 | 0.744 | 0.827 |

| CnnSeMpr [30] | 0.776 | 0.858 | 0.824 | 0.709 | 0.808 |

| VGG16 [31] | 0.835 | 0.900 | 0.866 | 0.790 | 0.857 |

| VGG16SeMpr | 0.818 | 0.893 | 0.849 | 0.774 | 0.843 |

| InResV2 [32] | 0.847 | 0.911 | 0.860 | 0.828 | 0.866 |

| InResV2Att [33] | 0.844 | 0.895 | 0.868 | 0.809 | 0.876 |

| DBAL | 0.864 | 0.918 | 0.876 | 0.847 | 0.881 |

Fig. 11.

ROC curve of each network on dataset A

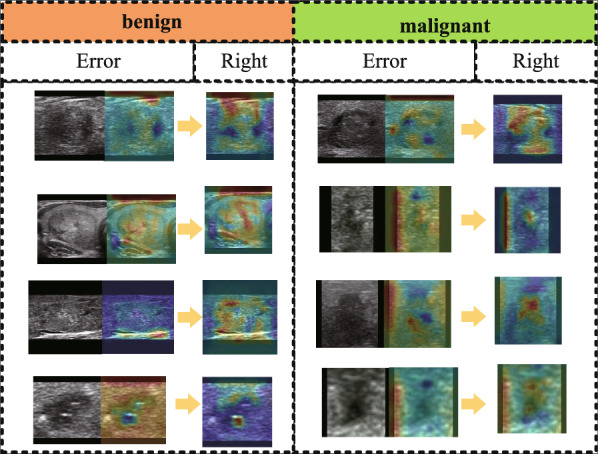

In our study, we performed an analysis of the coarse localization in the AOLB network (as shown in Fig. 12) and found that the attention-based localization branch demonstrated remarkable effectiveness. Additionally, we conducted a statistical analysis of the misclassified dataset and plotted a heat map of the coarse localization, revealing that classification errors were caused by inaccurate coarse localization results. Therefore, it is essential to improve the feature extraction capability of the second branch to enhance the overall performance of the model.

Fig. 12.

Feature distribution in the last Conu_5c convolution layer of AOLB, and the red dotted line box is the coarse location results of nodules extracted by AOLB

Overall, the dual branch model DBAL proposed in this article has good performance in coarse and fine granularity feature extraction and classification, and can be applied to current related fields. It has certain guidance and reference value for the development of CAD systems in similar scenarios. As for breast ultrasound grading in the field of medical imaging, it also uses ultrasound images to capture overall and local features, and then performs discrimination, similar to the thyroid ultrasound image scene used in this article; Expanding further, the model and ideas proposed in this article are also applicable to most problems in fine-grained image classification (FGVC). For example, for images with similar targets and environments, this model can extract overall features at coarse granularity for target localization, and then further extract detailed features from multiple local targets at fine granularity for classification.

Ablation experiment

To verify the effectiveness of the dual-branch training structure, we conducted ablation studies by removing the attention object location branch (AOLB) and the attention part proposal branch (APPB) separately (Table 3). When AOLB is removed, the optimal accuracy obtained from the original branch is reduced by 3.6%, indicating that AOLB first locates the object subject and extracts overall features, which has a certain gain effect on classification. Similarly, when removing APPB, the optimal accuracy obtained from object branches decreased by 3.1%, indicating that in the face of unstable localization results in AOLB, APPB can compensate for the shortcomings of coarse-grained models and enhance their robustness by further fine-grained feature extraction. Our experiments have shown that these two branches play an important role in achieving high accuracy in the final classification.

Table 3.

Compares the results of using different branch

| Backbone | ACC | AUC | sen | spec | f1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOLB | 0.854 | 0.905 | 0.863 | 0.821 | 0.870 |

| APPB | 0.849 | 0.901 | 0.870 | 0.821 | 0.826 |

| AOLB + APPB | 0.885 | 0.937 | 0.915 | 0.845 | 0.902 |

Conclusion

In this study, we have proposed a convolutional neural network-based CAD system for automatic classification of thyroid nodules. By incorporating prior knowledge-based feature extraction in a two-branch detection network, we have demonstrated improved classification accuracy compared to existing CAD methods for thyroid nodules. Our system achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 0.864 on dataset A, surpassing the performance of baseline methods. To address the limited amount of annotated data, we introduced self-supervised learning using the thyroid nodule puzzle task for pre-training. This enabled us to learn relevant features of thyroid ultrasound in advance and fine-tune the model with annotated data during supervised learning. Pre-training resulted in a 2.1% improvement in performance compared to without pre-training, and our CAD system exhibited better accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

However, there are some limitations to our proposed CAD system. Firstly, the dataset used for constructing and evaluating the system (dataset A) exhibited an imbalance in the categories, with more malignant nodules than benign nodules. This imbalance restricted the improvement of specificity, and further data collection is necessary to address this limitation. Additionally, our annotations were relatively rough, ranging from rough nodule location to fine-grained classification. While this approach significantly reduces annotation costs, it may lead to the omission of certain features. Furthermore, the resolution of the collected images was relatively low, so future work will focus on noise reduction in ultrasound images and techniques to enhance image resolution. Finally, given the abundance of medical image data sources, we aim to extend our method to other medical tasks for clinical applications. Overall, while our proposed CAD system demonstrates improved performance for thyroid nodule classification, further refinements and validation on diverse datasets are necessary to address the limitations and enhance the system’s robustness and applicability.

Acknowledgements

This work was guided and supported by Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2022A1515140033), Guangdong Provincial Drug Administration (Grant No. 2022YDZ06), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62073086) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2022A 1515011445)

Funding

This work was guided and supported by Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2022A1515140033), Guangdong Provincial Drug Administration (Grant No. 2022YDZ06), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62073086) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2022A 1515011445)

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to restrictions .Their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have checked the manuscript and have agreed to the submission.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yifei Xie and Zhengfei Yang have contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Qiyu Yang, Email: yangqiyu@gdut.edu.cn.

Yu-Jing Lu, Email: luyj@gdut.edu.cn.

Jiaxun Wang, Email: drwang2141@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):438–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ospina NS, Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Castro MR. Thyroid nodules: diagnostic evaluation based on thyroid cancer risk assessment. BMJ. 2020;368:l6670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl D, Leboulleux S, Locati LD, Newbold K, Papotti MG, Berruti A. Thyroid cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(12):1856–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedraza L, Vargas C, Narváez F, Durán O, Muñoz E, Romero E. An open access thyroid ultrasound image database. In: 10th international symposium on medical information processing and analysis, vol 9287. SPIE; 2015. p. 188–93.

- 5.Kwak JY, Han KH, Yoon JH, Moon HJ, Son EJ, Park SH, Jung HK, Choi JS, Kim BM, Kim EK. Thyroid imaging reporting and data system for us features of nodules: a step in establishing better stratification of cancer risk. Radiology. 2011;260(3):892–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lingam RK, Qarib MH, Tolley NS. Evaluating thyroid nodules: predicting and selecting malignant nodules for fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. Insights Imaging. 2013;4(5):617–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acharya UR, Swapna G, Sree SV, Molinari F, Gupta S, Bardales RH, Witkowska A, Suri JS. A review on ultrasound-based thyroid cancer tissue characterization and automated classification. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2014;13(4):289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acharya UR, Chowriappa P, Fujita H, Bhat S, Dua S, Koh JE, Eugene LW, Kongmebhol P, Ng KH. Thyroid lesion classification in 242 patient population using Gabor transform features from high resolution ultrasound images. Knowl Based Syst. 2016;107:235–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavendra U, Acharya UR, Gudigar A, Tan JH, Fujita H, Hagiwara Y, Molinari F, Kongmebhol P, Ng KH. Fusion of spatial gray level dependency and fractal texture features for the characterization of thyroid lesions. Ultrasonics. 2017;77:110–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kattenborn T, Leitloff J, Schiefer F, Hinz S. Review on convolutional neural networks (CNN) in vegetation remote sensing. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2021;173:24–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song W, Li S, Liu J, Qin H, Zhang B, Zhang S, Hao A. Multitask cascade convolution neural networks for automatic thyroid nodule detection and recognition. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2018;23(3):1215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Yang C, Huang J, Liu S, Zhuo Y, Xu L. Deep learning framework based on integration of S-Mask R-CNN and Inception-v3 for ultrasound image-aided diagnosis of prostate cancer. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;114:358–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, Guo Q, Lian C, Ren X, Liang S, Jing Yu, Niu L, Sun W, Shen D. Automated detection and classification of thyroid nodules in ultrasound images using clinical-knowledge-guided convolutional neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2019;58:101555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Y, Jiang S-Q, Sun B, Siuly S, Şengür A, Tian J-W. Using neutrosophic graph cut segmentation algorithm for qualified rendering image selection in thyroid elastography video. Health Inf Sci Syst. 2017;5:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taleb A, Loetzsch W, Danz N, Severin J, Gaertner T, Bergner B, Lippert C. 3D self-supervised methods for medical imaging. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:18158–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shurrab S, Duwiari R. Self-supervised learning methods and applications in medical imaging analysis: a survey. PeerJ Comput Sci 2022;8:e1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Chen L, Bentley P, Mori K, Misawa K, Fujiwara M, Rueckert D. Self-supervised learning for medical image analysis using image context restoration. Med Image Anal. 2019;58:101539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang P, Wang F, Zheng Y. Self supervised deep representation learning for fine-grained body part recognition. In: 2017 IEEE 14th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2017). IEEE; 2017. p. 578–82.

- 19.Bai W, Chen C, Tarroni G, Duan J, Guitton F, Petersen SE, Guo Y, Matthews PM, Rueckert D. Self-supervised learning for cardiac MR image segmentation by anatomical position prediction. In: Medical image computing and computer assisted intervention—MICCAI 2019: 22nd international conference, Shenzhen, China, October 13–17, 2019, proceedings, part II 22. Springer, 2019. p. 541–9.

- 20.Taleb A, Lippert C, Klein T, Nabi M. Multimodal self-supervised learning for medical image analysis. In: Information processing in medical imaging: 27th international conference, IPMI 2021, virtual event, June 28–June 30, 2021, proceedings. Springer; 2021. p. 661–73.

- 21.Noroozi M, Favaro P. Unsupervised learning of visual representations by solving jigsaw puzzles. In: Computer vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, proceedings, part VI. Springer; 2016. p. 69–84.

- 22.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016. p. 770–8.

- 23.Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Kim EK, Kim MJ. A taller-than-wide shape in thyroid nodules in transverse and longitudinal ultrasonographic planes and the prediction of malignancy. Thyroid. 2011;21(11):1249–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anil G, Hegde A, Chong FHV. Thyroid nodules: risk stratification for malignancy with ultrasound and guided biopsy. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11(1):209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei X-S, Luo J-H, Jianxin W, Zhou Z-H. Selective convolutional descriptor aggregation for fine-grained image retrieval. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2017;26(6):2868–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sermanet P, Eigen D, Zhang X, Mathieu M, Fergus R, LeCun Y. Overfeat: integrated recognition, localization and detection using convolutional networks. arXiv Preprint. 2013. http://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6229.

- 27.Al-Dhabyani W, Gomaa M, Khaled H, Fahmy A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief. 2020;28:104863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigues PS. “Breast ultrasound image” Mendeley data v1. 2019. Available from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/wmy84gzngw/1. Accessed 3 Apr 2023.

- 29.Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60(6):84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo X, Zhao H, Tang Z. An improved deep learning approach for thyroid nodule diagnosis. In: 2020 IEEE 17th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI). IEEE; 2020. p. 296–9.

- 31.Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv Preprint. 2014. http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556.

- 32.Wang L, Zhang L, Zhu M, Qi X, Yi Z. Automatic diagnosis for thyroid nodules in ultrasound images by deep neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2020;61:101665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szegedy C, Ioffe S, Vanhoucke V, Alemi A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In: Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol 31. 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to restrictions .Their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.