Summary:

Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe, life-threatening soft tissue infection that presents as a surgical emergency. It is characterized by a rapid progression of inflammation leading to extensive tissue necrosis and destruction. Nonetheless, the diagnosis might be missed or delayed due to variable and nonspecific clinical presentation, contributing to high mortality rates. Therefore, early diagnosis and prompt, aggressive medical and surgical treatment are paramount. In this review, we highlight the defining characteristics, pathophysiology, diagnostic modalities, current principles of treatment, and evolving management strategies of necrotizing fasciitis.

Takeaways

Question: Summarizing current data to provide practical insight into management of necrotizing fasciitis (NF) to guide plastic surgeons who might manage NF in their daily practice.

Findings: This study is a comprehensive practical review of various aspects of NF, including potential future therapies, its current classification, and management.

Meaning: NF is a clinical diagnosis and surgical emergency that usually requires serial debridement. Reconstruction options after debridement include skin grafting, flaps, and other various techniques based on the wound location and extent.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a rapidly progressing soft tissue infection that aggressively spreads along fascial layers and subcutaneous tissues.1–3 Common sites of infection include the extremities, abdomen, and perineum. NF can be idiopathic or secondary (after trauma, chronic wounds, or skin abrasions).4,5 Diagnosis can often be challenging and is primarily diagnosed based on clinical presentation. NF has a mortality rate of 8.7%–76%, underscoring the need for timely and accurate diagnosis and prompt medical and surgical treatment.3 This practical review will focus on the basic tenets of NF, including classification, comorbidities related to NF, clinical presentation and diagnosis, and nonsurgical and surgical management principles.

CLASSIFICATION

NF is classified as types I–IV (Table 1).6–12 Type I, the most common, is the polymicrobial type, accounting for 70%–90% of all NF cases.6 To qualify under this NF type, pathogenic bacteria need to consist of at least two microorganisms. On the other hand, type II NF is a monomicrobial infection commonly attributed to beta-hemolytic Streptococcus A (GAS or S. pyogenes).7,8 Less commonly Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), including the methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (10%–30% incidence), can be the causative pathogen. MRSA increases the level of complexity and may lead to toxic shock syndrome, resulting in a more unfavorable outcome.9,10 The most common pathogens isolated in type III NF infection are Clostridium pathogens, Vibrio species, and gram-negative bacteria.8,12 Type IV infections consist of fungal infections, most commonly Candida species and zygomycetes.11

Table 1.

Classification of NF

| Type | Common Locations | Infectious Profile | Common Microorganisms | Vulnerable Populations | Important Nuances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (most common) | Perineum, trunk, groin, abdominal wall | Polymicrobial | ≥1 anaerobic (nontypable streptococci and Enterobacteriaceae) + aerobic (Gram + or Gram −) | Mostly immunocompromised Patients Newborns (a complication of omphalitis) |

Chronic illnesses/immunosuppression (diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, chronic renal failure, HIV, chronic cardiac/pulmonary disease) Recreational drug use (I.V. drug misuse, alcohol abuse) trauma (blunt/penetrating trauma, surgery, burns) Nutritional issues (obesity, malnutrition) |

| Type II (less common) | Extremities, head & neck |

Monomicrobial | β-hemolytic group-A streptococcus Staphylococcus aureus Other streptococci |

Mostly immunocompetent individuals with a history of recent trauma/operation | Toxic shock syndrome (30% of cases) |

| Type III (uncommon) | Extremities, trunk, perineum |

Monomicrobial |

Vibrio species (Vibrio vulnificus Vibrio damsela Vibrio parahaemolyticus) Clostridium species Gram-negative bacteria Aeromonas hydrophila |

Vibrio: following minor injuries exposed to salt water Clostridium: Injury/Surgical wounds, drug addicts Aeromonas: Seafood consumption |

Fulminant course Multiorgan failure, if untreated |

| Type IV (very rare) | Extremities, trunk, perineum |

Fungal | Candida species Zygomycetes | Mostly after trauma/burns in immunocompetent individuals severely immunocompromised individuals | Aggressive especially in immunocompromised |

COMORBIDITIES

The most common comorbidity associated with NF is diabetes mellitus, which has not been directly associated with increased mortality.13–15 Other commonly associated comorbidities encompass the conditions causing immunosuppression or chronic illnesses characterized by immune dysfunction, such as IV drug use, alcohol use, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and Addison disease.16–20 Moreover, in these patients, progression to severe sepsis is more likely.21–24

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The diagnosis of NF can often be challenging during its early stages, as it usually presents with a classic triad of nonspecific signs: swelling, severe pain, and erythema.25 However, a prominent finding for NF is significant pain out of proportion to physical findings and beyond the involved skin because the infection spreads more quickly through fascia.26–28 In addition to the classic triad, early symptoms include local warmth, skin sclerosis, induration, foul “dishwasher” discharge, fever, and diarrhea. Patients are critically ill if they present late, often with septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, altered mental status, and extensive soft tissue necrosis.9 More advanced findings include bullae and crepitus.29 Even though NF can involve any body part, it most commonly affects the extremities, with an incidence of 36%–55%9 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, it frequently affects the trunk (18%–64%) and the perineum (up to 36%).30–34

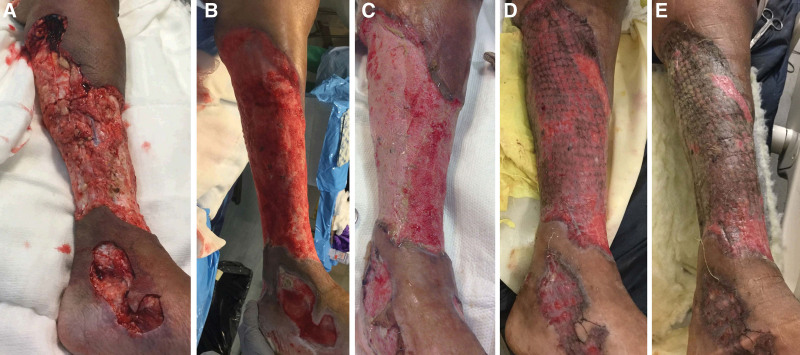

Fig. 1.

NF of the leg and foot. A-B, The wound before and after debridement, respectively. C-E, Stages of healing after skin grafting.

Diagnostic/Laboratory Tests

Certain laboratory tests assist in ruling out other alternative diagnoses. For instance, leukocytosis [white blood cells (WBC) > 20,000/L] is highly concerning for NF. Furthermore, elevated renal labs (BUN > 18 mg/dL and Cr > 1.2 mg/dL) are demonstrative for an acute renal injury, typically seen in NF patients. In addition, elevated creatinine kinase is common.35 One study suggested that C-reactive protein (CRP) > 16 mg/dL or CK > 600 IU/L should initiate a more extensive workup for GAS NF.36

The risk of NF can also be obtained using laboratory index measures based on serum parameters, clinical presentation, and associated comorbidities (Table 2).37–48 One such scoring tool is the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC), which classifies patients into risk categories with algorithms for diagnostic resources.38–41 However, the diagnostic value of LRINEC decreases in patients with multiple comorbidities (due to weakened inflammatory response) and after some hospital interventions, such as blood transfusion.42 Recently, the modified LRINEC score has been suggested, which adds liver disease and serum lactate levels to the equation while redefining the cut-off values for CRP, WBC, and Hgb. Another laboratory scoring test often used is Fournier Gangrene Severity Index, which assists the clinician in determining the necessity of surgical debridement.43–45 Laboratory and anamnestic risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis and site other than the lower limb, immunosuppression, age <60 years, renal impairment, and inflammatory markers (SIARI) scores are newer tools that have been deemed useful.47 Moreover, SIARI was shown to possess higher diagnostic ability than LRINEC score.48 However, it is essential to note that emergent debridement must be undertaken regardless of the laboratory index scoring, especially in cases with a high clinical suspicion.46

Table 2.

Summary of Laboratory Indices Used to Facilitate Diagnosis of NF

| Laboratory Index | Summary of Included Parameters | Parameters | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| LRINEC | Six common serum parameters at the time of presentation | CRP total WBC count Hemoglobin serum Na Creatinine glucose |

≥6 = higher risk of NF |

| MLRINEC |

Six common serum parameters + liver disease at the time of presentation | CRP total WBC count Hemoglobin serum Na Creatinine glucose Lactate liver disease |

≥12 = higher risk of NF |

| FGSI | Three vital signs + six serum markers | Temperature heart rate Respiration rate serum Na Serum K creatinine Hematocrit total WBC count Serum bicarbonate |

9 = cut-off value for NF >9 = mortality likelihood of 75% ≤9 = survival likelihood of 78% |

| SIARI | Four comorbidities + three serum markers | Site of infection outside the lower limb History of immunosuppression Age ≤ 60 Creatinine Inflammatory markers (total WBC count CRP) |

3 = cut-off value for NF 6–7 = moderate risk of NF ≥8 = high risk for NF |

| LARINF | Three comorbidities + three serum markers | Heart, liver, or renal insufficiency Immunosuppression (does not include diabetes) Obesity Procalcitonin CRP Hemoglobin |

≥5 = higher risk of NF |

Imaging

Imaging plays a critical role in diagnosing NF, especially in cases where the diagnosis is ambiguous. In cases of NF, X-ray imaging can demonstrate soft tissue gas (observed in 24.8%–55.0% of patients), strongly suggestive of Clostridium species.49,50 Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more sensitive and specific compared with plain radiography, and can reveal the degree of tissue infection, inflammation, fascial edema, and gas formation.51–53 Although MRI does have clinical utility, especially in equivocal cases of NF, it is important to note that MRI is cost-prohibitive for NF as a first diagnostic modality.54 Moreover, it delays the limb-saving intervention, which should ideally be performed within 12 hours of admission.3,55,56 Ultrasonography is also helpful and can assist in equivocal cases; ultrasonography can demonstrate hyperechoic foci with reverberation artifact and dirty shadowing at the site of infection,57 which signifies subcutaneous gas. Although this imaging modality can be beneficial, its biggest limitation lies in the outcome dependence on the ultrasonography skillset of the operator.

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

Surgical Treatment

The mainstay of treatment for NF consists of emergency surgical debridement of the infected tissue. Surgical management is especially indicated in NF with systemic inflammatory response syndrome or multiorgan failure, associated with a mortality rate of 70%.9,20 Moreover, surgery is mandatory for a patient experiencing severe pain with erythema, ecchymosis, blisters, or bullae.58

Surgery reduces bioburden by inhibiting the spread along the fascial planes.59 To minimize the risk of scarring and promote better wound healing, incisions are initially made parallel to the Langer lines.9 Incisions perpendicular with Langer lines can be made to keep the wound open and to allow further drainage and removal of necrotic tissue, except in cases of abdominal wall or retroperitoneal space involvement.12,20,60 Close ongoing surveillance over surgical wounds and tissue viability is required for the next 24 hours. In complex cases, repeat surgical debridement can be beneficial as a “second-look operation.”9,61

It is imperative to remove all nonviable or necrotic tissue,62 as the timing and the extent of the first debridement are the most important determining factors in mitigating the mortality rate.63 Delays in surgical debridement, necrosectomy, and fasciotomy (≥12 hours) may result in fulminant NF and higher mortality.9 For example, Ecker et al found that when surgery was delayed 24 hours, the mortality rate increased ninefold.62

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

Wounds with significant contamination and questionable tissue integrity have led surgeons to pursue the closure of tissue via delayed closure (87), including negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT).64 Vacuum-assisted closure systems (VAC) have been shown to reduce edema, substantially increase blood flow, reduce wound size, and decrease bacterial colonization in managing various wounds.65 Successful use of both black polyurethane66–69 and silver70,71 foam dressings in NF has been reported. Nonetheless, the authors did not provide the reasoning behind the preference for the specific sponge types.

Still, there is no consensus on the use of NPWT in NF.72 Although some authors experienced anaerobic infection development and progressive worsening of the patient on NPWT, others reported better infection control, sufficient granulation tissue, and more pain relief and odor reduction.72,73 Although direct application of NPWT/VAC on a debrided raw surface is hypothesized to increase the bleeding risk, such a complication was not recorded.72–74 Misiakos et al also observed the facilitation of wound closure with VAC use.3 The authors noted that despite being more expensive than gauze dressings, VAC did not reduce the hospital stay (P = 0.2). Therefore, they recommended limiting VAC application to more complex cases of NF (eg, NF with several comorbidities, large wounds).3

Coverage and Reconstruction

Reconstructive goals for the treatment of NF are reducing morbidity from the extensive tissue debridement and restoring functionality. After radical excision of necrotic, nonviable tissue, healing by delayed primary closure or secondary intention can be offered to cover small wounds.75 For larger/complex wounds, the reconstructive options include skin grafting [split (STSG)- and full-thickness], acellular dermal matrix, tissue expansion, and (pedicled and free) flaps.75,76

STSGs are one of the simplest and most used reconstructive techniques.75 Whallett et al reported successful skin grafting of upper (2) and lower (1) extremity wounds.77 Similar results were observed by Lemsanni et al with wound preparation with NPWT and subsequent skin grafting.78 The use of STSGs and full-thickness skin grafting for extremity wound reconstruction was also described by La Padula et al. In their case series, only one flap (dorsal metacarpal artery flap) was performed in a secondary procedure for interphalangeal joint resurfacing.79 Positive outcomes of skin grafting and NPWT for lower extremity NF have also been reported.80–82

Flaps with/without skin grafting may be used for complex and extensive defects. The flap choice usually depends on the region and wound requirements. For instance, pedicled latissimus dorsi (LD) and transverse rectus abdominis muscle flaps are suitable and popular options for chest wound reconstruction. In cases of unresolved infection, absence of vascular supply, extensive local damage, and defect depth, free flaps are preferred.75 Free LD, gastrocnemius, and soleus flaps are frequently used to cover extremity defects after debridement.83 Overall, the reverse radial forearm flap is one of the widely performed flaps for upper extremity reconstruction.83 Additionally, free and pedicled flaps are used to cover the upper extremity (radial forearm, LD, rectus abdominis, and pedicled groin flaps) and lower extremity (free gracilis, gastrocnemius, and soleus flaps) stumps after amputation.83 These procedures are relatively common, as up to one-quarter of NF patients still undergo amputation.78,79,84

Perineum Defects (Fournier Defects)

Several options are available to allow for adequate healing of a patient with NF of the perineum (Fournier gangrene). Goals of care include protective coverage and function of gonadal tissue and acceptable cosmesis. Due to the high prevalence of significant comorbidities in the at-risk population, single-stage procedures are often preferred.85

The perineum presents reconstructive challenges given the proximity of fecal and urine contamination, and at times, the usage of fecal and urinary diversion methods may be used.86 These techniques are performed particularly when gross sphincter involvement, more extensive wounds, severe incontinence, or patients in a severely immunocompromised state are present.86

Several options are available for closure: healing by secondary intention, loose soft tissue approximation, skin grafting, and flap coverage.87 If the wound is noted to be small and confined, healing by secondary intention is often used.85,88 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the best reconstruction method for a patient with Fournier gangrene. However, the algorithm by Chen et al can be used to guide the reconstruction of large defects. They recommend the use of the scrotal advancement flap (<50% of the scrotal surface) and pedicled anterolateral thigh (ALT) or pudendal thigh flap (>50% of the scrotal surface) for the reconstruction of the simple scrotal defects. For the complex defects involving the perineum, various flaps (pedicled ALT with/without vastus lateralis muscle, gracilis flap) with adjunctive VAC were suggested. If concomitant abdominal wall defect is present, STSG was recommended.58 Using this algorithm, the authors successfully treated 31 patients with a 16% complication rate.

Compared with skin grafting, flap reconstruction provides more durable and robust repair with decreased complications and improved cosmesis.8,89 The gracilis musculocutaneous flap is considered the workhorse flap for perineal reconstruction. However, other flaps, including local scrotal advancement, fasciocutaneous thigh, myocutaneous, and perforator flaps, have been used to repair NF perineal defects.89,90 Nonetheless, skin grafting is frequently performed, as well. Studies have reported several advantages to skin grafting, such as short operative times, low morbidity rates, adequate functionality, and cosmesis.91 Disadvantages include graft contraction and potential rejection secondary to shearing, infection, or hematoma formation.8

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

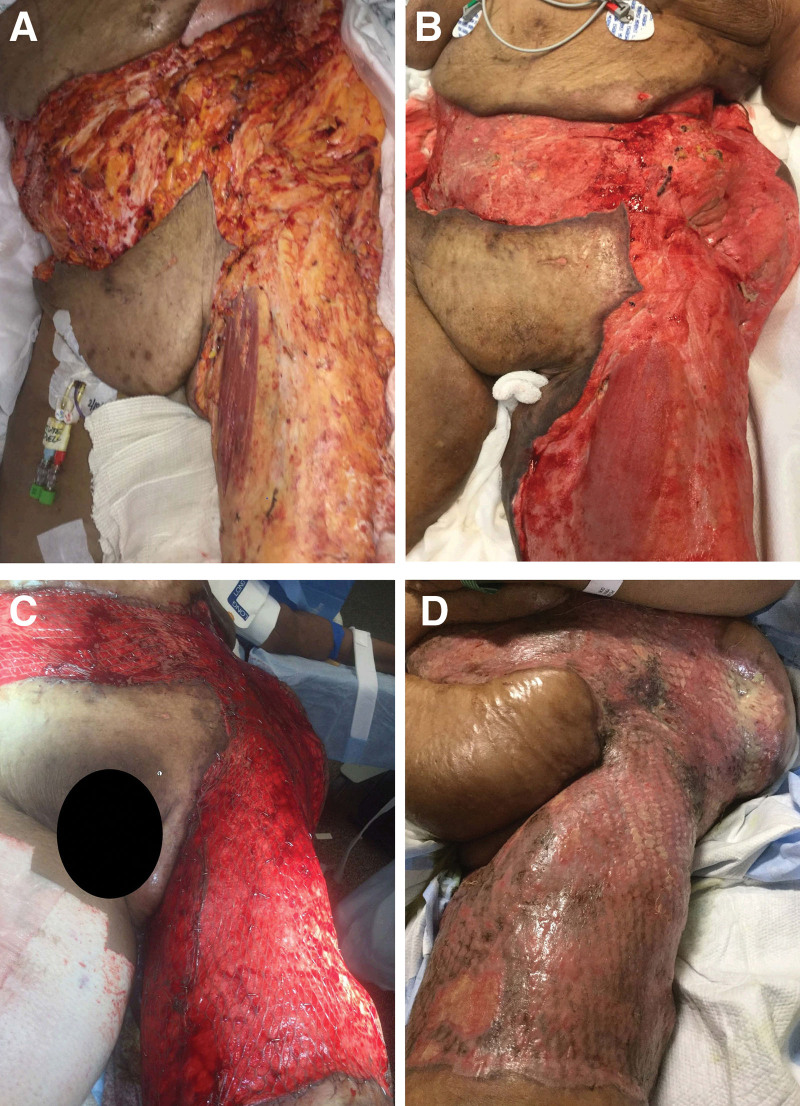

NF can result in extensive full-thickness defects of the abdominal wall, constituting a reconstructive challenge92 (Fig. 2). The primary goal of the reconstruction is to restore proper abdominal wall function and structure once an adequate necrosectomy is done. The long-term goals are to provide adequate skin closure, midline fascial closure, improved functionality, and good cosmesis.92

Fig. 2.

Improvement of abdominal and thigh NF with treatment. A, Initial NF wound. B, Wound appearance after surgical debridement. C, Immediate postoperative appearance of the wound after skin graft application. D, Integration of the skin graft.

Currently, the reconstructive technique is chosen based on the type of abdominal defect.93 Presence of the overlying skin bridge differentiates type I defects from type II defects.94 Type I defects are typically repaired with a component separation. Component separation with a biologic mesh is an option if tension-free primary repair of fascia cannot be conducted after the wound is sufficiently granulated and infection is controlled.12,95 Despite the infection risk, some authors have used synthetic mesh (Mersilene) to temporarily cover the abdominal defect until the infection is controlled.96

More complex constructive options are needed to repair type II defects. Autologous reconstruction has the advantage of avoiding the implantation of foreign mesh material, thereby reducing the risk of infection for the patient. Brafa et al97 used an abdominoplastic technique with advancement flaps and umbilical preservation after two months of repeated debridements and VAC application. Two other patients treated in a similar fashion (abdominoplasty with upper abdominal flap mobilization) were discharged approximately 2 weeks later.98 STSGs can be combined with local flaps for large wounds or used after the flap failure.96,99 Rectus femoris myocutaneous flap is another option for coverage of a large anterior abdominal wall defect.50 Free flaps (eg, tensor fasciae latae, ALT, LD, and gracilis) can be used to repair more extensive defects, and some may even provide motor functionality.95,100 TFL can be preferred over ALT only in the absence of an adequate perforator, which would also allow sufficient mobilization.86

Antibiotic Management

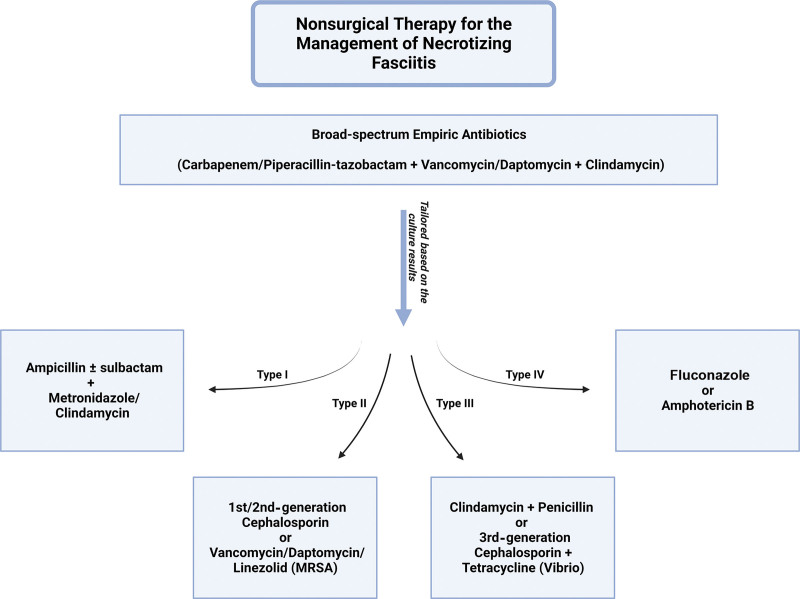

Immediately upon clinical concern for NF, the patient should be made NPO and admitted to the ICU to enable aggressive resuscitation.20,101 Broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms are recommended. A carbapenem (imipenem, meropenem, or ertapenem) or piperacillin–tazobactam plus vancomycin or daptomycin (good coverage against MRSA) plus clindamycin (for toxin-elaborating strains of GAS and S. aureus) are typically selected.102,103 Antibiotics can be tailored based on the NF microbiological classification criteria (based on history, gram stain, and culture of the polymicrobial infection).9 Antibiotic treatment for type 1 NF includes ampicillin/ampicillin–sulbactam combined with metronidazole or clindamycin.15,20,31,33,34 Gram-negative coverage (eg, ampicillin–sulbactam, piperacillin–tazobactam, ticarcillin–clavulanate acid, third-generation or fourth-generation cephalosporins, or carbapenems) is critical for initial antibiotic therapy for patients previously hospitalized and/or on antibiotics.9,104,105 In type 2 infections, S. pyogenes and S. aureus coverage is required; in most cases, first-generation or second-generation cephalosporins can be used. However, with MRSA, initial antibiotics should be replaced with vancomycin, or daptomycin and linezolid.9,74,104–107 Some studies have advised adding clindamycin to the antibiotic regimen when NF or myositis is present, as clindamycin’s mechanism of action (inhibition of protein synthesis) makes it more efficacious than penicillin.106,107 To adequately cover Clostridium species (type III NF), clindamycin and penicillin should be added to the antibiotic regimen.9,74,104–107 For fungal infection seen with type IV NF disease, antifungal treatment, such as fluconazole or amphotericin B, should be initiated (Fig. 3).9,104,105

Fig. 3.

Graphic description of antibiotic therapy in NF.

Antibiotic coverage should be continued for at least 5 days after resolving local and systemic signs and symptoms.105 Eventually, empiric antibiotic therapy can be weaned depending on the results of blood, wound, and tissue cultures.107 After source control, short (48 hours) antibiotic course is adequate.108 Patients diagnosed with NF typically remain on antibiotic treatment for 4–6 weeks.9

Future Therapies

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) and Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) have been suggested as adjunct treatments for NF. Research indicates that HBO improves patient survival while decreasing the number of surgical debridements and potentially the extent of reconstruction by inhibiting the systemic inflammatory response system and improving leukocyte activity.78,109 Moreover, it can facilitate the transport of some antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides.110 Risemann et al concluded that adjunct HBO therapy improved mortality from 66% to 23%.86 Unfortunately, the study outcomes on HBO therapy in NF remain inconsistent, and further evaluation and more extensive studies are needed.

IVIG has been shown to be beneficial in patients with GAS NF that progressed into toxic shock syndrome.74,111–113 Researchers have linked the efficacy of IVIG in NF to its ability to reduce a systemic inflammatory response by targeting the exotoxins.114 IVIG has also shown some benefits in high-risk patients, including those with advanced age, bacteremia, and hypotension.115 However, in a large-scale study of NF patients with shock, no benefit of adjunctive IVIG therapy was documented.116 Therefore, IVIG’s role in the management of NF is still debatable.

CONCLUSIONS

NF is a rapidly progressive and potentially life-threatening soft tissue infection, most commonly affecting the extremities. Clinical presentation is the key factor for diagnosis, and a high level of clinical concern should prompt immediate medical intervention and aggressive surgical debridement to optimize patient survival. Initial treatment includes broad-spectrum antibiotics and aggressive debridement. Adjunctive NPWT can significantly improve postoperative wound outcomes. Finally, the patient may undergo reconstruction once the patient is medically stable, and patient’s nutritional status and wound have been optimized. Although most patients benefit from skin grafting, local, pedicled, and free flaps; mesh; and acellular dermal matrix alone or in combination can be used based on the wound (eg, location, size) and patient (eg, comorbidities, adjacent injuries) characteristics. Timely diagnosis, early and extensive debridement, close postoperative surveillance, wound care, adequate wound closure, and management of complications are essential to improve patient outcomes.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Janis receives royalties from Springer Publishing and Thieme Publishers. The other authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Published online 19 January 2024.

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rüfenacht MS, Montaruli E, Chappuis E, et al. Skin-sparing débridement for necrotizing fasciitis in children. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:489e–497e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horta R, Nascimento R, Silva A, et al. The free-style gluteal perforator flap in the thinning and delay process for perineal reconstruction after necrotizing fasciitis. Wounds. 2016;28:200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Papadopoulos I, et al. Early diagnosis and surgical treatment for necrotizing fasciitis: a multicenter study. Front Surg. 2017;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang M, Chen L, Chi K, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis complicated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome after breast augmentation with fat from the waist and lower extremities: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520937623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taviloglu K, Cabioglu N, Cagatay A, et al. Idiopathic necrotizing fasciitis: risk factors and strategies for management. Am Surg. 2005;71:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilton BD, Zibari GB, McMillan RW, et al. Aggressive surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis serves to decrease mortality: a retrospective study. Am Surg. 1998;64:397–400; discussion 400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puvanendran R, Huey JC, Pasupathy S. Necrotizing fasciitis. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:981–987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancerotto L, Tocco I, Salmaso R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: classification, diagnosis, and management. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anaya DA, McMahon K, Nathens AB, et al. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Arch Surg. 2005;140:151–157; discussion 158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton MD, Fowler JE, Sharifi R, et al. Causes, presentation and survival of fifty-seven patients with necrotizing fasciitis of the male genitalia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davoudian PNJ. Flint, necrotizing fasciitis. Cont Educ Anaesthesia Crit Care Pain. 2012;12:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roje Z, Roje Z, Matić D, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: literature review of contemporary strategies for diagnosing and management with three case reports: torso, abdominal wall, upper and lower limbs. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinschek A, Evers B, Lampl L, et al. Prognostic aspects, survival rate, and predisposing risk factors in patients with Fournier’s gangrene and necrotizing soft tissue infections: evaluation of clinical outcome of 55 patients. Urol Int. 2012;89:173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green RJ, Dafoe DC, Raffin TA. Necrotizing fasciitis. Chest. 1996;110:219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong CH, Wang YS. The diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamenkovic I, Lew PD. Early recognition of potentially fatal necrotizing fasciitis the use of frozen-section biopsy. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1689–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkerson RW, Paull Coville FV. Necrotizing fasciitis: review of the literature and case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987(216):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontes RA, Jr., Ogilvie CM, et al. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter PS, Banwell PE. Necrotising fasciitis: a new management algorithm based on clinical classification. Int Wound J. 2004;1:189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, et al. Current concepts in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014;1:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong CH, Chang H-C, Pasupathy S, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1454–1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott D, Kufera JA, Myers RA. The microbiology of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Am J Surg. 2000;179:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh G, Sinha SK, Adhikary S, et al. Necrotising infections of soft tissues—a clinical profile. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss KA, Laverdière M. Group A Streptococcus invasive infections: a review. Can J Surg. 1997;40:18–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizokami F, Furuta K, Isogai Z. Necrotizing soft tissue infections developing from pressure ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2014;23:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas AJ, Meyer TK. Retrospective evaluation of laboratory-based diagnostic tools for cervical necrotizing fasciitis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2683–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreasen TJ, Green SD, Childers BJ. Massive infectious soft-tissue injury: diagnosis and management of necrotizing fasciitis and purpura fulminans. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majeski J, Majeski E. Necrotizing fasciitis: improved survival with early recognition by tissue biopsy and aggressive surgical treatment. South Med J. 1997;90:1065–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang TL, Hung CR. Role of tissue oxygen saturation monitoring in diagnosing necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahmouni A, Chosidow O, Mathieu D, et al. MR imaging in acute infectious cellulitis. Radiology. 1994;192:493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brothers TE, Tagge DU, Stutley JE, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging differentiates between necrotizing and non-necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid MR, Kossmann T, Duewell S. Differentiation of necrotizing fasciitis and cellulitis using MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagano N, Isomine S, Kato H, et al. Human fulminant gas gangrene caused by Clostridium chauvoei. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1545–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naqvi GA, Malik SA, Jan W. Necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity: a case report and current concept of diagnosis and management. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapman SJ, Opdam H, Donato R, et al. Successful management of severe group A streptococcal soft tissue infections using an aggressive medical regimen including intravenous polyspecific immunoglobulin together with a conservative surgical approach. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:742–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulla ZD. Treatment options in the management of necrotising fasciitis caused by Group A Streptococcus. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1695–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimbelman J, Palmer A, Todd J. Improved outcome of clindamycin compared with beta-lactam antibiotic treatment for invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:1096–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome—a comparative observational study. The Canadian Streptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barry W, Hudgins L, Donta ST, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for toxic shock syndrome. JAMA. 1992;267:3315–3316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bechar J, Sepehripour S, Hardwicke J, et al. Laboratory risk indicator for necrotising fasciitis (LRINEC) score for the assessment of early necrotising fasciitis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:341–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong C-H, Khin L-W, Heng K-S, et al. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1535–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosshardt TL, Henderson VJ, Organ CH, Jr. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Arch Surg. 1996;131:846–852; discussion 852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu PH, Wu K-H, Hsiao C-T, et al. Utility of modified laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (MLRINEC) score in distinguishing necrotizing from non-necrotizing soft tissue infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doluoğlu Ö G, et al. Overview of different scoring systems in Fournier’s gangrene and assessment of prognostic factors. Turk J Urol. 2016;42:190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:672–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Breidung D, Malsagova AT, Loukas A, et al. Causative micro-organisms in necrotizing fasciitis and their influence on inflammatory parameters and clinical outcome. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2022;24:46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cribb BI, Wang MTM, Kulasegaran S, et al. The SIARI score: a novel decision support tool outperforms LRINEC score in necrotizing fasciitis. World J Surg. 2019;43:2393–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tso DK, Singh AK. Necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity: imaging pearls and pitfalls. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20180093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marron CD, McArdle GT, Rao M, et al. Perforated carcinoma of the caecum presenting as necrotising fasciitis of the abdominal wall, the key to early diagnosis and management. BMC Surg. 2006;6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mok MY, Wong SY, Chan TM, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis in rheumatic diseases. Lupus. 2006;15:380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roje Z, Roje Z, Eterović D, et al. Influence of adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy on short-term complications during surgical reconstruction of upper and lower extremity war injuries: retrospective cohort study. Croat Med J. 2008;49:224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee NH, Kim GE, Choi HJ. Necrotizing fasciitis due to late-onset group B streptococcal bacteremia in a 2-month-old girl. Pediatr Emerg Med J. 2022;9:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kwak BO, Lee MJ, Park HW, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome secondary to varicella in a healthy child. Korean J Pediatr. 2014;57:538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ, Petrinic D, et al. Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Ann Surg. 1995;221:558–563; discussion 563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalaivani V, Hiremath BV. Necrotising soft tissue infection–risk factors for mortality. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2013;7:1662–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang KC, Shih CH. Necrotizing fasciitis of the extremities. J Trauma. 1992;32:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen SY, Fu J-P, Chen T-M, et al. Reconstruction of scrotal and perineal defects in Fournier’s gangrene. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Insua-Pereira I, Ferreira PC, Teixeira S, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: a review of reconstructive options. Cent European J Urol. 2020;73:74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carvalho JP, Hazan A, Cavalcanti AG, et al. Relation between the area affected by Fournier’s gangrene and the type of reconstructive surgery used A study with 80 patients. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leppäniemi A, Tukiainen E. Reconstruction of complex abdominal wall defects. Scand J Surg. 2013;102:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ecker KW, Baars A, Töpfer J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum and the abdominal wall-surgical approach. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34:219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karian LS, Chung SY, Lee ES. Reconstruction of defects after Fournier gangrene: a systematic review. Eplasty. 2015;15:e18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mathes SJ, Steinwald PM, Foster RD, et al. Complex abdominal wall reconstruction: a comparison of flap and mesh closure. Ann Surg. 2000;232:586–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jallali N, Withey S, Butler PE. Hyperbaric oxygen as adjuvant therapy in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2005;189:462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El-Sabbagh AH. Negative pressure wound therapy: an update. Chin J Traumatol. 2017;20:103–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frankel JK, Rezaee RP, Harvey DJ, et al. Use of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation in the management of cervical necrotizing fasciitis. Head & Neck. 2015;37:E157–E160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crew JR, Varilla R, Allandale Rocas Iii T, et al. Treatment of acute necrotizing fasciitis using negative pressure wound therapy and adjunctive neutrophase irrigation under the foam. Wounds. 2013;25:272–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leiblein M, Marzi I, Sander AL, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: treatment concepts and clinical results. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44:279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Paula FM, Pinheiro EA, de Oliveira VM, et al. A case report of successful treatment of necrotizing fasciitis using negative pressure wound therapy. Medicine (Baltim). 2019;98:e13283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Melchionda F, Pession A. Negative pressure treatment for necrotizing fasciitis after chemotherapy. Pediatr Rep. 2011;3:e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen SJ, Chen YX, Xiao JR, et al. negative pressure wound therapy in necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chester DL, Waters R. Adverse alteration of wound flora with topical negative-pressure therapy: a case report. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55:510–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong CH, Yam AK-T, Tan AB-H, et al. Approach to debridement in necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196:e19–e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tessier JM, Sanders J, Sartelli M, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: a focused review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, operative management, antimicrobial therapy, and pediatrics. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2020;21:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Danielsson PA, Fredriksson C, Huss FR. A novel concept for treating large necrotizing fasciitis wounds with bilayer dermal matrix, split-thickness skin grafts, and negative pressure wound therapy. Wounds. 2009;21:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whallett EJ, Stevenson JH, Wilmshurst AD. Necrotising fasciitis of the extremity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:e469–e473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lemsanni M, Najeb Y, Zoukal S, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the upper extremity: a retrospective analysis of 19 cases. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2021;40:505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.La Padula S, Pensato R, Zaffiro A, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the upper limb: optimizing management to reduce complications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Swain RA, Hatcher JC, Azadian BS, et al. A five-year review of necrotising fasciitis in a tertiary referral unit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95:57–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hodgins N, Damkat-Thomas L, Shamsian N, et al. Analysis of the increasing prevalence of necrotising fasciitis referrals to a regional plastic surgery unit: a retrospective case series. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wiberg A, Carapeti E, Greig A. Necrotising fasciitis of the thigh secondary to colonic perforation: the femoral canal as a route for infective spread. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1731–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Somasundaram J, Wallace DL, Cartotto R, et al. Flap coverage for necrotising soft tissue infections: a systematic review. Burns. 2021;47:1608–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kao LS, Lew DF, Arab SN, et al. Local variations in the epidemiology, microbiology, and outcome of necrotizing soft-tissue infections: a multicenter study. Am J Surg. 2011;202:139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sikora CA, Spielman J, Macdonald K, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis resulting from human bites: a report of two cases of disease caused by group A streptococcus. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16:221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Riseman JA, Zamboni WA, Curtis A, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for necrotizing fasciitis reduces mortality and the need for debridements. Surgery. 1990;108:847–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huayllani MT, Cheema AS, McGuire MJ, et al. Practical review of the current management of Fournier’s gangrene. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;10:e4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stevens DL, Tanner MH, Winship J, et al. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Darabi K, Abdel-Wahab O, Dzik WH. Current usage of intravenous immune globulin and the rationale behind it: the Massachusetts General Hospital data and a review of the literature. Transfusion. 2006;46:741–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.El-Khatib HA. V-Y fasciocutaneouspudendal thigh flap for repair of perineum and genital region after necrotizing fascitis: modification and new indication. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;48:370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Takei S, Arora YK, Walker SM. Intravenous immunoglobulin contains specific antibodies inhibitory to activation of T cells by staphylococcal toxin superantigens [see comment]. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:602–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schrage B, Duan G, Yang LP, et al. Different preparations of intravenous immunoglobulin vary in their efficacy to neutralize streptococcal superantigens: implications for treatment of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:743–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu SL, Tsai C-Y, Luo Y-H, et al. Kallistatin modulates immune cells and confers anti-inflammatory response to protect mice from group A streptococcal infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5366–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nisbet M, Ansell G, Lang S, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: review of 82 cases in South Auckland. Intern Med J. 2011;41:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dalsgaard A, Frimodt-Møller N, Bruun B, et al. Clinical manifestations and molecular epidemiology of Vibrio vulnificus infections in Denmark. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsai HL, Liu C-S, Chang J-W, et al. Severe necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall secondary to colon perforation in a child. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brafa A, Grimaldi L, Brandi C, et al. Abdominoplasty as a reconstructive surgical treatment of necrotising fasciitis of the abdominal wall. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e136–e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schumacher H, Tehrani H, Irwin MS, et al. Abdominoplasty as an adjunct to the management of peri-Caesarian section necrotising fasciitis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:807–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tan LGL, See JY, Wong KS. Necrotizing fasciitis after laparoscopic colonic surgery: case report and review of the literature. Surg Laparoscopy Endoscopy Percutaneous Tech. 2007;17:551–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Srinivas JS, Panagatla P, Damalacheru MR. Reconstruction of type II abdominal wall defects: anterolateral thigh or tensor fascia lata myocutaneous flaps? Indian J Plast Surg. 2018;51:33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wallace HA, Perera TB. Necrotizing fasciitis, In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2022. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430756/. Accessed December 5, 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hua C, Urbina T, Bosc R, et al. Necrotising soft-tissue infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;23:e81–e94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bonne SL, Kadri SS. Evaluation and management of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Voros D, Pissiotis C, Georgantas D, et al. Role of early and extensive surgery in the treatment of severe necrotizing soft tissue infection. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1190–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:563–576; discussion 577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Silberstein J, Grabowski J, Parsons JK. Use of a vacuum-assisted device for Fournier’s gangrene: a new paradigm. Rev Urol. 2008;10:76–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Terzian WTH, Nunn AM, Call EB, et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy in necrotizing soft tissue infections: shorter is safe. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2022;23:430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wilkinson D, Doolette D. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment and survival from necrotizing soft tissue infection. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mallikarjuna MN, Vijayakumar A, Patil VS, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: current practices. ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:942437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ferreira PC, Reis JC, Amarante JM, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: a review of 43 reconstructive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mouës CM, van den Bemd GJCM, Heule F, et al. Comparing conventional gauze therapy to vacuum-assisted closure wound therapy: a prospective randomised trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:672–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—A case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;4:260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Peetermans M, de Prost N, Eckmann C, et al. Necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infections in the intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Souyri C, Olivier P, Grolleau S, et al. ; French Network of Pharmacovigilance Centres. Severe necrotizing soft-tissue infections and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kadri SS, Swihart BJ, Bonne SL, et al. Impact of intravenous immunoglobulin on survival in necrotizing fasciitis with vasopressor-dependent shock: a propensity score–matched analysis from 130 US hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;64:ciw871–ciw885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]