Abstract

Supported,

bimetallic

catalysts have shown great promise for the

selective hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. In this study,

we decipher the catalytically active structure of Ni–Ga-based

catalysts. To this end, model Ni–Ga-based catalysts, with varying

Ni:Ga ratios, were prepared by a surface organometallic chemistry

approach. In situ differential pair distribution function (d-PDF)

analysis revealed that catalyst activation in H2 leads

to the formation of nanoparticles based on a Ni–Ga face-centered

cubic (fcc) alloy along with a small quantity of GaOx. Structure refinements of the d-PDF data enabled us to determine

the amount of both alloyed Ga and GaOx species. In situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy experiments confirmed

the presence of alloyed Ga and GaOx and

indicated that alloying with Ga affects the electronic structure of

metallic Ni (viz., Niδ−). Both the Ni:Ga ratio

in the alloy and the quantity of GaOx are

found to minimize methanation and to determine the methanol formation

rate and the resulting methanol selectivity. The highest formation

rate and methanol selectivity are found for a Ni–Ga alloy having

a Ni:Ga ratio of ∼75:25 along with a small quantity of oxidized

Ga species (0.14  molNi–1).

Furthermore, operando infrared spectroscopy experiments indicate that

GaOx species play a role in the stabilization

of formate surface intermediates, which are subsequently further hydrogenated

to methoxy species and ultimately to methanol. Notably, operando XAS

shows that alloying between Ni and Ga is maintained under reaction

conditions and is key to attaining a high methanol selectivity (by

minimizing CO and CH4 formation), while oxidized Ga species

enhance the methanol formation rate.

molNi–1).

Furthermore, operando infrared spectroscopy experiments indicate that

GaOx species play a role in the stabilization

of formate surface intermediates, which are subsequently further hydrogenated

to methoxy species and ultimately to methanol. Notably, operando XAS

shows that alloying between Ni and Ga is maintained under reaction

conditions and is key to attaining a high methanol selectivity (by

minimizing CO and CH4 formation), while oxidized Ga species

enhance the methanol formation rate.

Keywords: bimetallic catalysts, CO2 hydrogenation, nickel, gallium, in situ, operando, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, X-ray total scattering, pair distribution function

1. Introduction

The selective hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol (eq 1) enables us to convert a greenhouse gas, CO2, into a value-added product of high global demand, making this process a sustainable alternative to the commercial methanol synthesis based on syngas and reforming technology.1 Notably, the industrial catalyst used in the commercial process, viz., Cu/ZnO/Al2O3, suffers from deactivation and low methanol selectivity when used under CO2 hydrogenation conditions (eq 2).1,2 The main causes for catalyst deactivation include sintering of the active Cu0 nanoparticles3 and ZnO,4 oxidation of Cu,4 and poisoning of the active sites by hydroxyl groups at high concentrations of H2O or CO2.5

| 1 |

| 2 |

In that context, research efforts have been undertaken to improve Cu-based catalysts,6 as well as explore alternative metal-based catalysts such as Ni, Pd, and Au,2,7,8 focusing on understanding the nature of the active sites and the role of additional metals/metal oxides, which is critical to allow for a knowledge-driven catalyst design. For example, Ga-promoted transition metal catalysts, such as Cu–Ga,9−12 Ni–Ga,13−17 and Pd–Ga,18−22 have shown promising activity for the CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. In these catalysts, Ga was present in the form of an alloy that in many cases9,12,14,18 coexisted with oxidized Ga species under reaction conditions. The promotional effect of Ga in Ni is particularly noteworthy as Ni-based catalysts are typically very effective in the methanation reaction (eq 3).23 The introduction of Ga, forming Ni–Ga intermetallics (ordered alloys), has been shown however to improve the selectivity toward methanol, reaching up to ca. 60%.14

| 3 |

This finding has triggered research into understanding the role of Ga in the CO2 hydrogenation pathway, the relationship between Ni–Ga phases and catalyst performance, and ultimately the structure of the active sites in this promising catalyst family.13−15,24,25 Previous works based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations have linked the δ-Ni5Ga3 phase to high methanol yields,13 while more recent studies on Ga-doped Ni(211) surfaces have argued that Ni is the active site and that alloying with Ga modifies the electronic structure of Ni through an electron transfer from Ga, promoting in turn the formation of oxygenates (methanol and CO) over methane.15,26,27

Despite these previous research efforts, the structure of the active sites in the Ni–Ga system has not been elucidated unequivocally. Two major challenges have limited progress in answering this central research question, viz., the lack of model catalyst systems with precise control over size, phase, and composition (i.e., Ni:Ga ratio) and the lack of detailed information concerning the catalyst structure (electronic and geometric) under operando conditions. With regard to the synthesis of Ni–Ga catalysts, previous works reported challenges in obtaining well-defined nanoparticles of a single phase as conventional approaches such as impregnation lead typically to catalysts containing multiple phases (e.g., both δ-Ni5Ga3 and α′-Ni3Ga),14,16,25,28 or mixtures of alloys and gallium oxide, which makes it impossible to identify the catalytically active motif.14,25,29,30 Furthermore, it has been reported that the oxidation of Ga to Ga2O3 species can promote methanol formation.14 Indeed, dealloying under CO2 hydrogenation conditions has been reported for related bimetallic M–M′ systems (Cu–Ga,9,12 Cu–Zn,31 and Pd–Ga18), generating a mixture of both metallic M (Cu/Pd) and (partially) oxidic M′ (Ga/Zn) species. Similarly, the ratio of M/M′ in bimetallic catalysts has been shown to have a pronounced influence on the catalyst activity, transitioning from promoting to poisoning effects.10 In the specific case of Ni–Ga, the δ-Ni5Ga3 phase has been proposed to be particularly active for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol, putting forward questions related to the optimal Ni:Ga ratio as well as the stability and the role of the alloy and/or the oxide interface on methanol selectivity and formation rate.

To shed light on these questions, we synthesized

tailored Ni–Ga-based

catalysts with varying Ni:Ga ratios and constant particle sizes (∼2

nm) using surface organometallic chemistry (SOMC)32,33 and thermolytic molecular precursor (TMP)34 approaches and interrogated (quantitatively) their structure under

operando conditions using a combination of X-ray-based characterization

techniques. In situ and operando differential pair distribution function

(d-PDF) analysis of X-ray total scattering data and X-ray absorption

spectroscopy (XAS) revealed that after activation in H2, the most selective catalyst contained nanoparticles with an fcc

Ni–Ga alloy structure with a ratio Ni:Ga = 75:25 and a small

quantity of oxidized Ga species, GaOx (0.14  molNi–1).

The presence of GaOx appreciably increased

the methanol formation rate while maintaining a high methanol selectivity

when compared with a catalyst that contains an identical Ni–Ga

alloy composition (Ni:Ga = 75:25) but a smaller GaOx content (0.06

molNi–1).

The presence of GaOx appreciably increased

the methanol formation rate while maintaining a high methanol selectivity

when compared with a catalyst that contains an identical Ni–Ga

alloy composition (Ni:Ga = 75:25) but a smaller GaOx content (0.06  molNi–1).

The structure of the catalysts formed after activation was maintained

under reaction conditions (20 bar CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1, 230 °C), i.e., the quantities of Ga alloyed

and GaOx species remained constant. Furthermore,

operando diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy

(DRIFTS) provided additional insight into the surface species under

reaction conditions whereby only the most active catalyst showed bands

due to formate species. Combining these findings, we were able to

conclude that the alloying of Ni with Ga is key to attaining a high

methanol selectivity, while the presence of oxidized Ga species enhances

appreciably the rate of methanol formation.

molNi–1).

The structure of the catalysts formed after activation was maintained

under reaction conditions (20 bar CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1, 230 °C), i.e., the quantities of Ga alloyed

and GaOx species remained constant. Furthermore,

operando diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy

(DRIFTS) provided additional insight into the surface species under

reaction conditions whereby only the most active catalyst showed bands

due to formate species. Combining these findings, we were able to

conclude that the alloying of Ni with Ga is key to attaining a high

methanol selectivity, while the presence of oxidized Ga species enhances

appreciably the rate of methanol formation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalyst Synthesis

We prepared a series of silica-supported Ni–Ga-based catalysts with varying Ni:Ga ratios via a SOMC-TMP approach (Figure 1A).35 Briefly, in all of the Ni-containing materials, Ni was introduced by grafting [Ni(CH3)2(tmeda)] onto the surface OH groups of GaIII/SiO2 (or SiO2, in case of the monometallic Ni material), whereby GaIII/SiO2 was produced by grafting [Ga(OSi(OtBu)3)3(THF)] onto SiO2 as reported previously.36 All materials were subsequently treated under H2 at 600 °C for 12 h, which yielded the as-prepared catalysts, denoted as NixGa(100–x)/SiO2, where x is the nominal catalyst composition. The nominal Ni loading was kept constant at ca. 2 wt %, while the Ga loading was varied to obtain the desired nominal ratios of Ni:Ga (100:0, 75:25, 70:30, 65:35). The reference material Ga100/SiO2 (ca. 0.9 wt % Ga) was obtained by treating GaIII/SiO2 under H2 at 600 °C for 12 h. The final composition of the as-prepared catalysts was determined by elemental analysis (inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy, ICP-OES) and will be denoted as xICP (Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S1).

Figure 1.

(A) Synthesis of bimetallic NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 catalysts. (B) STEM image with the corresponding particle size distribution and (C) STEM-EDX image with overlaid Ni and Ga EDX signals of as-reduced Ni65Ga35/SiO2, selected here as a representative example for the TEM images of all NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 presented in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Catalyst Composition, as Determined by ICP, Molar Ratio of Ni:Ga (−) in the fcc-NiyGa(100–y) Alloy, and Molar Amounts of GaOx and Gaalloyed Normalized by the Catalysts’ Total Ni Content, as Determined by PDF and ICP Analyses.

| Catalyst | xICP in NixGa(100–x) (−) | Molar ratio of Ni:Ga in the fcc-NiyGa(100–y) alloy (−) | Gaalloyed (molGaalloyed molNi–1) | GaOx ( molNi–1) molNi–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni65Ga35/SiO2 | 67.5 | 74:26 | 0.34 | 0.14 |

| Ni70Ga30/SiO2 | 71.9 | 75:25 | 0.33 | 0.06 |

| Ni75Ga25/SiO2 | 76.4 | 82:18 | 0.23 | 0.08 |

Ex situ high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images of the as-prepared materials recorded under air-free conditions showed well-dispersed nanoparticles on the SiO2 support with an average diameter of around 2 nm (Figure 1B and Supporting Information Figures S1, S5, S8, and S12). These STEM images further confirmed that the SOMC-based synthesis approach yielded catalysts of very similar particle size, independent of the Ni:Ga ratio. Hence, any change in product formation rates could not be attributed to changes in the surface area of the nanoparticles. Furthermore, STEM-EDX images of Ni100/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 showed a spatial overlap between the Ni and Ga EDX signals in all of the as-prepared materials (Figure 1C and Supporting Information Figures S7, S10, and S14). Turning to the reference Ga100/SiO2, Ga was found to be highly dispersed with no visible nanoparticle formation (Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4), in line with previous studies.35

2.2. Structure of the Catalysts after In Situ Activation

Prior to CO2 hydrogenation

experiments, the catalysts

were activated in 1 bar H2 at 600 °C for 1 h, and

this process was monitored by in situ d-PDF and XAS. Here, we focus

on the analysis of the catalyst structure obtained after their in

situ activation. The evolution of the air-exposed catalysts during

activation is described in the Supporting Information. d-PDF was obtained

by subtracting the PDF signal of the support (i.e., SiO2) from the PDF data of the entire catalyst (Figures 2A and S22).37,38 For the d-PDF analysis of in situ activated Ni100/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, synchrotron X-ray total scattering data were collected

at the reaction temperature of 230 °C in 1 bar H2.

The SiO2-subtracted X-ray total scattering and d-PDF data

of the in situ activated catalysts are shown in Figures S21 and 2B (data collected

at 230 °C). The reciprocal space data of the activated catalysts

showed broad, yet clear Bragg peaks for all of the catalysts that

can be indexed, independent of the Ni:Ga ratio, as a face-centered

cubic (fcc)-type structure (Supporting Information Figure S21). Modeling of the d-PDF confirmed that all the

nanoparticles have an fcc type structure and revealed an average diameter

of the nanoparticles of ca. 2 nm that was invariant to the catalysts’

elemental composition, in line with STEM-EDX measurements (Supporting

Information Figure S27). In addition, fitting

of the d-PDF data revealed an increase in the cubic lattice parameter

of the fcc-NiyGa(100–y) alloy [where y:(100–y) is the Ni:Ga ratio in the alloy] with increasing Ga content,

which was attributed to the incorporation of Ga into the (nano)alloy

structure, causing a tensile strain in the fcc lattice (Figure 2D, Supporting Information Table S3). In line with the formation of Ni–Ga

alloys, d-PDF modeling also revealed an increase in the atomic displacement

factors (ADFs) with respect to Ni100/SiO2 due

to a broader distribution of interatomic distances in the alloys (Supporting

Information Figure S28).39 The agreement factors (Rw)

in all of the fittings were in the range of 0.17–0.23 which

are typical values for the PDF of small nanoparticles.40,41 It is possible that defects inside and/or on the surface of the

nanoparticles led to some misfit between the experimental data and

the calculated PDF (e.g., slight misfit in the intensity of the peaks

between 5 and 7 Å, Figure 2B), which are often present in nanoparticles;42,43 however, the peak positions of the PDF are well explained by the

models. The lattice parameters extracted from the fitting of the d-PDF

data were independent of the r-range fitted (1.7–25

Å) as shown in Figures 2D and S31. This indicates that

the local and midrange structures of the alloy are comparable. Concerning

the detection of oxidized species by d-PDF, it has to be stated that

the detection of Ga–O pairs by d-PDF is challenging (expected

at ca. 1.7–2.0 Å)44 due to

the presence of termination (noise) ripples arising from the finite Q-range,45 and the low scattering

cross-section of oxygen atoms relative to that of the higher Z elements Ni and Ga.46 Notably,

the fcc Ni–Ga alloys (bulk) follow Vegard’s law, i.e.,

there is a linear relationship between the Ni:Ga ratio and the cell

parameter (Supporting Information Table S4).47 However, when plotting the cell parameters

extracted from the supported nanoparticles against the catalysts’

composition determined by ICP (Figure 2D) together with the predicted cell parameters using

Vegard’s law (dashed curve), we observe that the determined

cell parameters were lower than the values expected from Vegard’s

law, indicating that not all of the Ga in the catalyst was incorporated

into the fcc structure of the (alloy) nanoparticles and hence remained

as oxidized Ga species (GaOx), as confirmed

by XAS (vide infra). Thus, we next quantified the amount of alloyed

Ga species (Gaalloyed) via Vegard’s law, and the

amount of GaOx as the difference between

the catalyst’s total Ga content measured by ICP and Gaalloyed (see Table 1 and the Supporting Information Section 3.1 for details).

A key observation from this analysis was that the lattice parameters

of the alloy phases in Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 were equal within

the error of the fitting, corresponding to an fcc alloy of composition

Ni:Ga = 75:25 in both materials, despite the fact that Ni65Ga35/SiO2 had a higher total Ga content than

Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (Tables 1 and S1 in the

Supporting Information). Thus, Ni65Ga35/SiO2 contained a larger quantity of GaOx (0.14  molNi–1) than

Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.06

molNi–1) than

Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.06  molNi–1).

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the composition of the alloy

nanoparticles in Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 was the same as the

composition of the (intermetallic) α′-Ni3Ga

phase. From our data, we could not exclude an ordering of the metals

in the catalysts as in the α′-Ni3Ga intermetallic

phase due to the very similar structure of fcc alloys and α′-Ni3Ga. The random fcc alloy (with a composition Ni:Ga = 75:25)

differs from the ordered α′-Ni3Ga only in

the occupancy of Ni and Ga in the fcc sites: in the random alloy,

Ga and Ni atoms randomly occupy the same sites, whereas in α′-Ni3Ga, Ga sits only at the corners and Ni in the center of the

faces of the cubic unit cell (see Supporting Information Figure S30). Due to the reduced symmetry of the

α′-Ni3Ga structure (being a superstructure

of the fcc structure) compared to that of the fcc random alloy, additional

low-intensity reflections would be expected in its diffraction pattern.48 However, since Ni and Ga have very similar scattering

properties, it is challenging to detect such weak reflections. Similarly,

only tiny differences would be expected in the magnitude of the PDF

peaks. However, previous reports have shown that intermetallic phases

are only formed above a certain critical nanoparticle size,49−51 and thus, we hypothesize that it is unlikely that ordering took

place in ∼2 nm-sized (nano)alloys.

molNi–1).

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the composition of the alloy

nanoparticles in Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 was the same as the

composition of the (intermetallic) α′-Ni3Ga

phase. From our data, we could not exclude an ordering of the metals

in the catalysts as in the α′-Ni3Ga intermetallic

phase due to the very similar structure of fcc alloys and α′-Ni3Ga. The random fcc alloy (with a composition Ni:Ga = 75:25)

differs from the ordered α′-Ni3Ga only in

the occupancy of Ni and Ga in the fcc sites: in the random alloy,

Ga and Ni atoms randomly occupy the same sites, whereas in α′-Ni3Ga, Ga sits only at the corners and Ni in the center of the

faces of the cubic unit cell (see Supporting Information Figure S30). Due to the reduced symmetry of the

α′-Ni3Ga structure (being a superstructure

of the fcc structure) compared to that of the fcc random alloy, additional

low-intensity reflections would be expected in its diffraction pattern.48 However, since Ni and Ga have very similar scattering

properties, it is challenging to detect such weak reflections. Similarly,

only tiny differences would be expected in the magnitude of the PDF

peaks. However, previous reports have shown that intermetallic phases

are only formed above a certain critical nanoparticle size,49−51 and thus, we hypothesize that it is unlikely that ordering took

place in ∼2 nm-sized (nano)alloys.

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic representation of a X-ray total scattering experiment and the resulting d-PDF data. (B) d-PDF data fitted to a fcc-NiyGa(100–y) alloy. (C) Zoom into the region r = 2–4.75 Å of the d-PDF data. The inset plots the fitted position of the metal–metal pair correlation labeled A as a function of xICP in the catalysts. (D) Cubic lattice parameter as a function of the fraction of Ni, as determined by elemental analysis. The error bars are represented by the area shaded in gray. Conditions: 1 bar H2, 230 °C, after in situ activation.

To probe the electronic and local structure of Ga and Ni, we performed XAS experiments at the Ni and Ga K-edges. XANES analysis provided insight into the metal oxidation states, while EXAFS yielded quantitative information concerning the local structure of Ni and Ga in the materials. In this context, it is worth noting that Ga K-edge XAS is more sensitive in probing for the presence of GaOx species than d-PDF. In the in situ XAS experiments, the same capillary reactor cell was used as in the d-PDF experiments, allowing to directly confront the respective results. Due to limited synchrotron beamtime, the in situ XAS experiments were performed on the catalyst with the highest Ga content (Ni65Ga35/SiO2), one with lower Ga content (Ni75Ga25/SiO2) and the references Ni100/SiO2 and Ga100/SiO2 (collected ex situ in airtight capillaries).

The in situ acquired Ni K-edge XANES spectra of the catalysts (after activation and collected at 50 °C) are presented in Figure 3A. The edge position [determined as the maximum of the first derivative of the normalized absorption μ(E)] was at ca. 8333 eV in all of the catalysts, indicating that Ni is in its metallic state, and no oxidized Ni species were present in the activated catalysts. Taking a closer look into the second edge feature labeled as “b” revealed a shift to lower energies for Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (by ca. −1.2 eV at μnorm = 0.6 au) and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (by ca. −0.5 eV at μnorm = 0.6 au) with respect to Ni100/SiO2. Moreover, the shape of the XANES features of Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga25/SiO2 in the white line region was different from that of Ni100/SiO2 and the Ni foil. According to previous studies, the observed XANES features in Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga25/SiO2 were interpreted as an electron transfer from Ga to Ni in the Ni–Ga alloy (Gaδ+/Niδ−), whereby the electron transfer was most pronounced in Ni65Ga35/SiO2 due to the higher content of Ga in the alloy, in line with d-PDF analysis (vide supra).52,53

Figure 3.

XAS data of the activated catalysts and reference materials: (A) normalized Ni K-edge XANES of Ni65Ga35/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, and Ni100/SiO2 and a Ni-foil reference. Line “a” denotes the position of the maximum of the first derivative of the Ni K-edge XANES of Ni foil (8333 eV). Inset “b” shows a shift of the Ni absorption edge to lower energies with increasing Ga content, indicating the formation of Niδ− species upon alloying of Ni with Ga. (B) Normalized Ga K-edge XANES of Ni65Ga35/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, and Ga100/SiO2, as well as the α′-Ni3Ga and GaIII/SiO2 references. The dotted lines represent difference XANES (Δi = i – α′-Ni3Ga). Experimental and fitted Fourier transforms of the (C) Ni K-edge and (D) Ga K-edge EXAFS data (plots not corrected for the phase shift). The contributions of the individual Ni–M, Ga–M (M = Ni,Ga), and Ga–O coordination spheres to the fits are shown as shaded areas. Conditions: 1 bar H2, 50 °C, after in situ activation.

Turning to Ga K-edge XANES, the respective data

of the activated

catalysts are plotted in Figure 3B together with α′-Ni3Ga as

a reference for a Ni–Ga alloy and GaIII/SiO2 as a reference for a material containing only Ga3+ (where Ga3+ is in tetrahedral coordination with oxygen

as reported previously).36 In addition,

we collected Ga K-edge XANES data of activated Ga100/SiO2, which also contains Ga3+ indicated by the white

line feature at ca. 10375.0 eV. However, activated Ga100/SiO2 also exhibits a feature at ca. 10371.5 eV, which

can be assigned to Ga+ and/or Ga hydride species ([GaH2]+ or [GaH]2+), that were formed during

activation in H2.54,55 Here, we refer to this

mixture of Ga species as GaOx (representing

a mixture of Ga3+/ Ga+/ Ga hydride species).54,55 The energy positions of the Ga K-edge in Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 were within 0.1 eV of that of the bulk α′-Ni3Ga reference, indicating that most Ga species were in an alloyed

state. Moreover, the Ga K-edge XANES spectra of both catalysts exhibited

two main features at 10368.0 and 10377.0 eV, which were due to Ga

alloyed with Ni. In fact, these features were present in α′-Ni3Ga and have been assigned to transitions to unoccupied Ga

4p states which are hybridized with Ni 3d/non-d bands of α′-Ni3Ga above the Fermi level.53 However,

the white line feature of Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (in the range

10370–10375 eV) had a higher intensity compared to that of

α′-Ni3Ga, suggesting the presence of a minor

quantity of oxidized Ga species in the activated catalysts. Indeed,

by evaluating the difference spectra (differences with respect to

α′-Ni3Ga, Figure 3B), we concluded that NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 contained predominantly Gaalloyed with some minor quantity

of GaOx species.54,56,57 Next, we performed linear combination fittings

(LCFs) of the Ga K-edge XANES data of Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 using α′-Ni3Ga and Ga100/SiO2 as references for the Gaalloyed and GaOx species, respectively. LCF analysis yielded a ratio

GaOx:Gaalloyed = 31:69 for

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and GaOx:Gaalloyed = 19:81 for Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (corresponding to 0.15 and 0.05  molNi–1 in

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2, respectively; Supporting Information Table S6 and Figures S33 and S34) in line with the values obtained in Table 1.

molNi–1 in

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2, respectively; Supporting Information Table S6 and Figures S33 and S34) in line with the values obtained in Table 1.

We note that linear combination using the α′-Ni3Ga and Ga100/SiO2 references resulted in the best agreement between the experimental data and the fit when compared to using the combination α′-Ni3Ga and GaIII/SiO2 or α′-Ni3Ga and β-Ga2O3, indicating the presence of GaOx in NixGa(100–x)/SiO2. Supplementary LCF results including an extended selection of Ga K-edge XANES references (Ga-foil, β-Ga2O3) can be found in the Supporting Information (Table S6, Figures S33 and S34). However, as the quantitative analysis of Ga K-edge XANES data containing multiple (alloyed and oxidized) species can be subject to errors, as the Ga features are affected in a convoluted fashion by the oxidation state, electronic interactions (e.g., from alloying), as well as the coordination environment in the oxide and the size and phases of the alloyed nanoparticles, additional EXAFS analysis was performed to probe in more detail the presence of Ga–O atomic pairs.

The k2-weighted EXAFS oscillations (k2Χ(k)) and the corresponding magnitude of the Fourier transform (FT) at the Ni K-edge of Ni100/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 are presented in Figures S38 and S40 in the Supporting Information and Figure 3C. We observed a first neighboring Ni–M shell (M = Ni, Ga) at ca. 2.2 Å and no evidence of a Ni–O shell, in line with XANES analysis. The EXAFS data at the Ga K-edge of Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 are presented in Figures 3D, S38 and S40 in the Supporting Information and evidenced a prominent Ga–M (M = Ni or Ga) shell and a weak Ga–O shell, indicative of a minor quantity of oxidized Ga species in line with XANES. Fitting the Ga and Ni K-edge EXAFS data allowed us to determine the average interatomic distances, coordination numbers (CN), and σ2 (the mean square variation in path length also referred to as Debye Waller factors) of the first Ni–M, Ga–M, and Ga–O shells (Supporting Information Table S8). This analysis revealed an increase in the average Ni–M distance with increasing Ga content, i.e., 2.48 < 2.50 < 2.53 Å for Ni100/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, respectively (Supporting Information Figure S41), in line with d-PDF analysis that showed an increase in the lattice parameter as Ga is incorporated into the Ni–Ga alloy fcc structure. The Ga–M distances were determined to be 2.52 Å in both Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, which were close to the Ni–M distances determined by EXAFS fitting of the Ni K-edge data. The σ2 values obtained for Ga–M were slightly higher than those for Ni–M, suggesting a somehow higher degree of disorder around Ga. The average CN for Ni100/SiO2 was 9(1) (number in parentheses represents the standard deviations obtained from the fittings), whereas in Ni75Ga25/SiO2, the CN(Ga–M) was close to CN(Ni–M) [i.e., CN(Ni–M) = 9.0(6), CN(Ga–M) = 9(2)] in line with an homogeneous distribution of Ga within the nanoalloy (i.e., no Ga or Ni surface segregation). In Ni65Ga35/SiO2, the CN(Ni–M) = 8.8(6) was slightly larger than CN(Ga–M) = 8.1(8), which we attribute to a larger quantity of oxidized Ga species (GaOx) in this catalyst, leading to a decrease in CN(Ga–M). Indeed, to fit the Ga K-edge EXAFS data of Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, a Ga–O path was required. The Ga–O distances were at ca. 1.84–1.87 Å with a CN of 0.6(3) and 0.7(1) for Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, respectively, providing further evidence for the presence of GaOx species in both catalysts. However, it was not possible to quantify the amount of GaOx species via EXAFS.

To summarize, the combined d-PDF and XAS

analyses show that Ni65Ga35/SiO2,

Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 contained alloyed nanoparticles of

∼2 nm in size with an

fcc structure along with small quantities of GaOx species. Using the extracted cell parameters and the ICP-determined

Ni and Ga contents in the catalysts, the alloy composition and the

quantity of GaOx were determined. Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2 contained alloy nanoparticles with a Ni:Ga

ratio of ca. 75:25, but Ni65Ga35/SiO2 contained more GaOx species (0.14  molNi–1) compared

to Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.06

molNi–1) compared

to Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.06  molNi–1).

On the other hand, Ni75Ga25/SiO2 contained

an alloy with a higher Ni:Ga ratio of 82:18 compared to Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2 along with a GaOx content

of 0.08

molNi–1).

On the other hand, Ni75Ga25/SiO2 contained

an alloy with a higher Ni:Ga ratio of 82:18 compared to Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2 along with a GaOx content

of 0.08  molNi–1, i.e.,

in between that of Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and

Ni70Ga30/SiO2. XAS supported the

findings of the d-PDF analysis in that Ni and Ga formed Ni–Ga

alloys and that there were minor quantities of oxidized Ga species

(ca. 0.05 and 0.15

molNi–1, i.e.,

in between that of Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and

Ni70Ga30/SiO2. XAS supported the

findings of the d-PDF analysis in that Ni and Ga formed Ni–Ga

alloys and that there were minor quantities of oxidized Ga species

(ca. 0.05 and 0.15  molNi–1 in

Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, respectively). Ni K-edge XANES data

pointed to a different electronic structure (electron transfer from

Ga to Ni) in the Ni–Ga catalysts compared to the monometallic

Ni reference (Ni100/SiO2) due to the alloying

of Ni with Ga.

molNi–1 in

Ni75Ga25/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2, respectively). Ni K-edge XANES data

pointed to a different electronic structure (electron transfer from

Ga to Ni) in the Ni–Ga catalysts compared to the monometallic

Ni reference (Ni100/SiO2) due to the alloying

of Ni with Ga.

2.3. Catalytic Performance and Role of Alloyed Ga and GaOx

We determined the

catalytic performance of the different materials under the following

CO2 hydrogenation conditions: fixed bed reactor, 25 bar,

CO2:N2:H2 = 1:1:3, 230 °C, and

a gas hourly space velocity of 60 L gcat–1 h–1. All product (methanol, CO, and CH4) formation

rates are normalized by the Ni content (Figure 4A) as Ni has been proposed as the active

site whereby its electronic structure is modified by neighboring Ga

atoms.15,26 Due to the small and invariant size of the

Ni–Ga nanoparticles in the catalysts (ca. 2 nm according to

d-PDF analysis), corresponding to a surface:volume ratio of 3:1 nm–1, we can infer that normalizing the product formation

rates by the total Ni content (ca. 2 wt % in all catalysts) offers

a meaningful basis for examining the impact of Ga addition on the

catalytic activity of Ni-based nanoparticles. The catalytic performance

per g of catalyst is reported in Table S1 in the Supporting Information. Interestingly, the rate of CO2 conversion decreases first by ca. 75% when transitioning

from Ni100/SiO2 (2.8  molNi–1 s–1) to Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (0.7

molNi–1 s–1) to Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (0.7  molNi–1 s–1) and

slightly increases again in catalysts with higher

nominal Ga contents in the following order: Ni75Ga25/SiO2 < Ni70Ga30/SiO2 < Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (Figure 4A). Notably, this

change of CO2 conversion rates was accompanied by a change

in product selectivity, viz., from mostly methane when using pure

Ni to methanol for Ni–Ga. The methanol formation rates of Ni100/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 were very similar, i.e., ca. 0.2 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1 but were significantly

higher for Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.6 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1) and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (1.1 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1), while Ga100/SiO2 did not convert any CO2 to any significant extent (Table S1). We would like to note here that methane and CO, but not methanol,

have been typically reported products from CO2 hydrogenation

over monometallic Ni/SiO2 catalysts. We hypothesize that

methanol formation over Ni100/SiO2 could be

due to the presence of very small Ni clusters which interact strongly

with the SiO2 support and show a different selectivity

profile compared to larger Ni nanoparticles.58 Generally, a remarkable shift in methanol selectivity was observed

upon the addition of Ga for the NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 series (Figure 4, Supporting Information Figure S17). Specifically, the methanol selectivity

increased in the following order: Ni100/SiO2 (7%) < Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (33%) <

Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (48%) < Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (54%). In parallel, while Ni100/SiO2 displayed a high methane selectivity (88%),

the methane selectivity decreased to 11% in Ni75Ga25/SiO2, and no methane was observed for Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2.

molNi–1 s–1) and

slightly increases again in catalysts with higher

nominal Ga contents in the following order: Ni75Ga25/SiO2 < Ni70Ga30/SiO2 < Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (Figure 4A). Notably, this

change of CO2 conversion rates was accompanied by a change

in product selectivity, viz., from mostly methane when using pure

Ni to methanol for Ni–Ga. The methanol formation rates of Ni100/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 were very similar, i.e., ca. 0.2 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1 but were significantly

higher for Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.6 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1) and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (1.1 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1), while Ga100/SiO2 did not convert any CO2 to any significant extent (Table S1). We would like to note here that methane and CO, but not methanol,

have been typically reported products from CO2 hydrogenation

over monometallic Ni/SiO2 catalysts. We hypothesize that

methanol formation over Ni100/SiO2 could be

due to the presence of very small Ni clusters which interact strongly

with the SiO2 support and show a different selectivity

profile compared to larger Ni nanoparticles.58 Generally, a remarkable shift in methanol selectivity was observed

upon the addition of Ga for the NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 series (Figure 4, Supporting Information Figure S17). Specifically, the methanol selectivity

increased in the following order: Ni100/SiO2 (7%) < Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (33%) <

Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (48%) < Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (54%). In parallel, while Ni100/SiO2 displayed a high methane selectivity (88%),

the methane selectivity decreased to 11% in Ni75Ga25/SiO2, and no methane was observed for Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni65Ga35/SiO2.

Figure 4.

(A) Product formation rates over NixGa(100–x)/SiO2. (B) Methanol formation rate and methanol selectivity (averaged over the first 180 min of TOS) as a function of xICP in NixGa(100–x)/SiO2, as determined by ICP. The insets plot the methanol formation rates and methanol selectivity as a function of the Gaalloyed content normalized by the catalysts’ Ni content. (C) Gaalloyed and GaOx contents as a function of xICP. The labels denote the molar ratio Ni:Ga in the alloy, as determined from PDF analysis. Shaded lines are guides to the eye.

To further analyze the role of the composition of the alloy and the quantity of GaOx in the catalytic performance of the series of catalysts studied, the rate of methanol formation, the methanol selectivity, SMeOH, and the quantities of Gaalloyed and GaOx normalized by the catalysts’ Ni contents are plotted as a function of the Ni:Ga ratio determined by ICP (xICP in NixGa(100–x)/SiO2, Figure 4B,C). Contrasting the individual trends, we observe that SMeOH increased quasi-linearly (in the range considered here) with the amount of Gaalloyed (Figure 4B, inset b). On the other hand, the methanol formation rate related nonlinearly with Gaalloyed and increased significantly once the composition of the alloy nanoparticle had reached the composition Ni:Ga = 75:25 (Figure 4B, inset a). Moreover, it was observed that for catalysts with an optimal alloy composition of Ni:Ga = 75:25 (ratio determined after activation according to d-PDF), an increase in the quantity of GaOx led to a significant increase in the rate of methanol formation (at a stable methanol selectivity).

2.4. Catalysts’ Structure during CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol Conditions

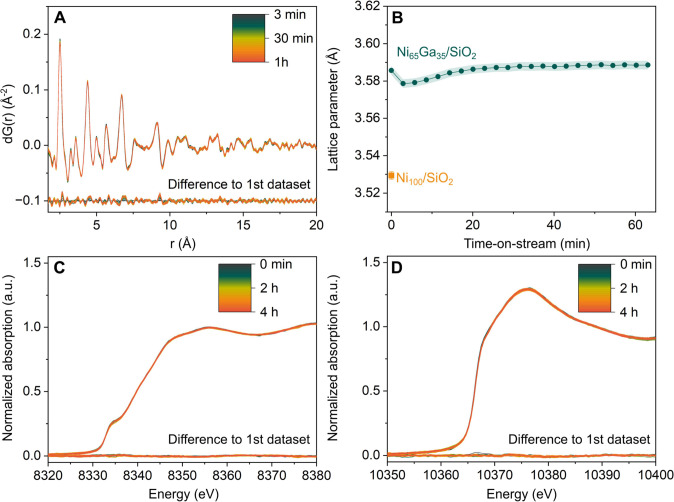

To track the catalyst structure and possible changes under reaction conditions, we further collected operando d-PDF and XAS data on the most active catalyst, i.e., Ni65Ga35/SiO2, under CO2 hydrogenation conditions (data collection started at the time of the gas switch from 20 bar N2 to 20 bar CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1 at 230 °C after the activation in hydrogen). We monitored the catalyst’s structure over ca. 3.5 h (total scattering) and 4 h (XAS) time-on-stream (TOS) (Figure 5). During the operando experiments, the outlet gas stream was analyzed online by gas-chromatography. In addition, similar operando d-PDF experiments were performed for Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 for 1 h TOS.

Figure 5.

Operando characterization of Ni65Ga35/SiO2. (A) d-PDF data collected over 60 min of TOS. The difference between each scan collected at TOS with respect to the first data collected after 3 min under reaction conditions. (B) Lattice parameter obtained via the fitting of the d-PDF shown in (A) as a function of TOS. The first value of the cell parameter (TOS = 0) corresponds to the value determined after catalyst activation (data collected in H2, Figure 2D). The lattice parameter obtained for activated Ni100/SiO2 is plotted for comparison. Normalized XANES collected over 4 h TOS at the (C) Ni K-edge and (D) Ga K-edge. Conditions: 20 bar, CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1, 230 °C.

d-PDF analysis revealed that the nanocrystalline fcc phase in Ni65Ga35/SiO2 remained stable under reaction conditions (Figure 5A, Supporting Information Figure S25); also, no growth in particle size was observed. We detected a minor increase by ca. 0.3% in the lattice parameter (from 3.579 to 3.589 Å, Figure 5B) within the first 60 min of TOS (to a lesser extent in Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2, Supporting Information Figure S24). The slight increase in the lattice parameters could be due to a temperature increase caused by the onset of the exothermic CO2 to methanol reaction (after the gases are switched from 20 bar N2 at TOS = 0 min to 20 bar CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1). It should be noted that a dealloying of the nanoparticles (i.e., oxidation of some Ga) would lead to a decrease in the lattice parameter, i.e., the opposite than what is observed experimentally.

Next, we evaluated whether changes in the oxidation state of Ga or Ni occurred under CO2 hydrogenation conditions. To probe possible changes in the XANES data with TOS, we calculated the difference (Δ) between the nth and the first XANES scan (with n ranging between the first and the final scan after ca. 4 h). The maximum difference in the magnitude of ΔXANES at the Ni- and Ga-K-edges was <0.05 in normalized absorption units (Figure 5C,D), indicating that no reduction nor oxidation of Ga took place under reaction conditions. This also implied that the small quantities of GaOx that were present after activation of the catalysts remained constant with TOS. We however do not exclude the possibility of alloying/dealloying of Ga taking place over extended catalyst operation times. In line with our XANES data and the observation of a stable fcc alloy phase from operando total scattering/PDF analysis, also the fitted EXAFS parameters of the reacted catalyst Ni65Ga35/SiO2 remained constant with respect to the activated catalyst (i.e., within the error of the fitting, see Supporting Information Table S8). These results indicated that the Ni–Ga alloy nanoparticles retained their structure and composition under CO2 hydrogenation conditions, with no evidence for dealloying/additional alloying, in agreement with the study of Hejral et al. using unsupported Ni–Ga nanoparticles.25 The behavior observed for Ni–Ga/SiO2 contrasts what have been observed for other bimetallic catalysts (i.e., Cu–Zn,31 Cu–Ga,10,12 Pd–Ga18) synthesized via the same SOMC approach used in this work, where dealloying, even if partial, was always observed under CO2 hydrogenation conditions.12,18,31,59,60 Note that the absence of bulk dealloying was also observed for the Au–Zn/SiO2 system (Au:Zn ca. 33:67).61 Also here, the Au–Zn alloy formed after catalyst activation (H2, 300 °C) and remained stable during CO2 hydrogenation conditions (10 bar CO2:H2:Ar = 1:3:1, 230 °C), while a minor oxidation of surface Zn was observed using operando XAS with a modulation of the gas-phase composition.

2.5. Surface Reaction Intermediates and Bound Adsorbates

To assess whether differences in the

catalysts’ structure

and composition (e.g., Ni:Ga ratio in the fcc alloy and quantity of

GaOx) affect the type and amounts of surface

adsorbate species and reaction intermediates, we performed operando

DRIFTS experiments on Ni65Ga35/SiO2, Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni75Ga25/SiO2, i.e., catalysts with distinctive

catalytic performance and structure. It is worth remembering that

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2 contained fcc alloy nanoparticles

with an identical Ni:Ga ratio (75:25) but different quantities of

GaOx (0.14 and 0.06  molNi–1 in

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2, respectively) allowing us to assess

the role of GaOx species on the observed

surfaces species. Further, Ni75Ga25/SiO2 contained an fcc alloy with a higher Ni:Ga ratio (82:12)

compared to Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2. Importantly, online analysis

of the off-gas during the operando DRIFTS experiments reproduced the

trend of the methanol formation rate observed in the catalytic packed

bed measurements (Supporting Information Figures S46–48), viz., the methanol formation rate decreases

in the order Ni65Ga35/SiO2 > Ni70Ga30/SiO2 > Ni75Ga25/SiO2.

molNi–1 in

Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2, respectively) allowing us to assess

the role of GaOx species on the observed

surfaces species. Further, Ni75Ga25/SiO2 contained an fcc alloy with a higher Ni:Ga ratio (82:12)

compared to Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2. Importantly, online analysis

of the off-gas during the operando DRIFTS experiments reproduced the

trend of the methanol formation rate observed in the catalytic packed

bed measurements (Supporting Information Figures S46–48), viz., the methanol formation rate decreases

in the order Ni65Ga35/SiO2 > Ni70Ga30/SiO2 > Ni75Ga25/SiO2.

In the operando DRIFTS data acquired, there are two spectral regions of interest (i) 1900–2200 cm–1 and (ii) 2600–3200 cm–1, in which Mn-COm (M = Ni,Ga) vibrations62 and C–H stretching vibrations63 are expected, respectively. Bands at ca. 2200–2450, 3500, and 3770 cm–1 are assigned to gaseous CO2(g) (see Table S10 in the Supporting Information for all the referenced band assignments).

In the region 1900 cm–1 - 2200 cm–1 (Supporting Information Figures S46–48), bands at 2077, 2094, and 2129 cm–1 were observed for all of the catalysts and were due to pressurized gaseous CO2(g).64 The first and most prominent band to appear after less than 10 min once the reaction gas mixtures has been introduced into the IR cell (range of 2049–2064 cm–1) could be assigned to Ni(CO)n (n = 1–4) surface adsorbate species and possibly also to gaseous Ni(CO)4(g).24,65−67

In the region 2600–3200 cm–1, two bands due to C–H stretching vibrations at 2860 and 2960–2962 cm–1 appeared on all catalysts independent of their composition. These bands started to appear at ca. 20–30 min after the introduction of a reaction gas mixture (Figure 6A–D). Previous studies on supported metal nanoparticle catalysts for methanol synthesis have assigned these bands to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching modes of methoxy groups (−OCH3) bonded to either the metal nanoparticles or the support.63 The band positions observed in our study (2860 and 2960–2962 cm–1) matched well with values reported for methoxy species adsorbed onto SiO2.68−70 Interestingly, on Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (i.e., the most active and selective catalyst), an additional band at 2898–2900 cm–1 was observed that can be assigned to ν(CH) of bidentate formate (b-HCOO);18 this band is absent in the other two catalysts, i.e., Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2. However, we do not exclude the presence of formate species in these catalysts, which could be present in a smaller extent compared to that of Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and are thus not detected and overshadowed with overlapping methoxy species in the IR spectrum. Note that two additional bands due to b-HCOO would be expected in the region 2800–3000 cm–1, which, however, overlap with the two bands assigned to methoxy species.18,71,72 Based on previous in situ IR studies on gallium oxides, the band at 2898–2900 cm–1 was likely due to b-HCOO on gallium oxide species,63,73 which was in agreement with our d-PDF and XAS analyses that indicated more abundant GaOx species (= binding sites of b-HCOO) on Ni65Ga35/SiO2 when compared to that on Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2. Hence, our experiments suggested that GaOx species (likely in proximity of the alloy nanoparticles) further promote the formation of formate species. According to the work of Collins et al.,73 bidentate formate species on gallium oxide also shows bands in the region 1300–1600 cm–1 (i.e., νas(CO2) at 1580 cm–1, δ(CH) at 1386 cm–1, νs(CO2) at 1372 cm–1) which, however, could not be observed unequivocally in our system due to the strong absorption of the incident IR radiation by SiO2 in this spectral region, leading to a poor signal-to-noise ratio.74 The presence of formate (in Ni65Ga35/SiO2) and methoxy bands in Ni65Ga35/SiO2, Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 was in line with the previously proposed mechanism for methanol formation, i.e., the formate–methoxy pathway (Figure 6E)24 and in line with what has been proposed for Cu.75 In addition, and in agreement with the formation of some methane in Ni75Ga25/SiO2 (Figure 6D), operando DRIFTS on Ni75Ga25/SiO2 showed the v3 stretching vibration of CH4(g) at 3016 cm–1, along with weak rotational bands of CH4 in the range 2600–3200 cm–1 (Supporting Information Figure S48). No bands due to CH4 were observed on Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2, i.e., catalysts that also did not show any methane formation or only negligible quantities in the packed bed experiments (Figure 6 A,C, Supporting Information Figures S46 and S47).

Figure 6.

(A) Operando DRIFTS for Ni65Ga33/SiO2 and (B) the corresponding baseline subtracted, intensity of the methoxy (H3CO*) and bidentate formate (b-HCOO*) bands and the measured methanol formation rate as a function of TOS. Operando DRIFTS for (C) Ni70Ga30/SiO2 and (D) Ni75Ga25/SiO2. TOS denotes the time after switching from 20 bar N2 to reaction conditions. Conditions: 20 bar, CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1, 230 °C, GHSV = 60 L gcat–1 h–1. (E) Schematic showing how methoxy and formate adsorbate species are potentially adsorbed on the catalyst surface.

3. Conclusions

In this study, we report

the synthesis of model catalysts containing

Ni–Ga nanoparticles supported on silica (NixGa(100–x)/SiO2) using a SOMC/TMP approach enabling a precise control over loading

and particle size and yielding highly active Ni–Ga-based catalysts

for the selective hydrogenation of CO2 into methanol, in

contrast to pure Ni that favors methanation. Combined electron microscopy,

operando d-PDF, and XAS studies showed that these silica-supported

catalysts contained, after their in situ activation in H2, ∼2 nm sized, Ni–Ga fcc alloy particles with a narrow

size distribution along with a small fraction of GaOx species. Furthermore, Ni K-edge XAS showed that the electronic

structure of Ni was affected by alloying and can be described as Niδ−Gaδ+. Using Vegard’s

law, the composition of the alloyed nanoparticles was determined as

Ni:Ga = 75:25 in activated Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni70Ga30/SiO2, whereas

the alloy in Ni75Ga25/SiO2 was more

Ni-rich (Ni:Ga = 82:12). Furthermore, considering the total Ga content

in the materials, as determined by elemental analysis, each catalyst

also contained residual GaOx. Notably,

the GaOx content in Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (0.14  molNi–1) was

more than double than that in Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.06

molNi–1) was

more than double than that in Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.06  molNi–1),

despite having an alloy with the same composition. Ni75Ga25/SiO2, having a more Ni-rich alloy, also

contained GaOx (0.08

molNi–1),

despite having an alloy with the same composition. Ni75Ga25/SiO2, having a more Ni-rich alloy, also

contained GaOx (0.08  molNi–1),

the quantity of which lies in between that of the other two catalysts.

molNi–1),

the quantity of which lies in between that of the other two catalysts.

Regarding catalysis, alloying Ni with Ga decreased its methanation

activity, while promoting methanol formation rates up to a certain

Ga content (Ni:Ga = 75:25). Ni65Ga35/SiO2, containing an alloy with a Ni:Ga ratio of 75:25 and the

largest amount of GaOx, showed the highest

methanol activity (1.1 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1) and selectivity (SMeOH = 54%)

and improved performance compared to Ni70Ga30/SiO2 (0.6 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1 and SMeOH = 48%) which contained

an alloy with the same composition (Ni:Ga = 75:25) but a lower GaOx content. Ni75Ga25/SiO2, containing a Ni-richer alloy and an intermediate amount

of GaOx, showed the poorest performance

(0.2 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1 and SMeOH = 33%) along with the monometallic

Ni catalyst (0.2 mmolMeOH molNi–1 s–1 and SMeOH = 7%) that favored methanation

( = 88%), as expected for

pure Ni. Hence,

both the amount of Ga in the alloy (Ni:Ga = 75:25) and Ga in the form

of GaOx are important for the methanol

production rate and selectivity. Importantly, operando d-PDF and XAS

analyses of the catalysts under CO2 hydrogenation conditions

revealed that the fcc structure of the alloy and the oxidation states

of Ni and Ga remained invariant with respect to the activated state

(treated under H2), indicating that the bulk alloy was

not affected by the reaction conditions, in sharp contrast to what

has been observed for Cu–Ga and Pd–Ga. Furthermore,

monitoring the catalysts by operando DRIFTS indicates that the presence

of GaOx helps in stabilizing formate species,

an important reaction intermediate in the methanol formation pathway,

further supporting the importance of GaOx.

= 88%), as expected for

pure Ni. Hence,

both the amount of Ga in the alloy (Ni:Ga = 75:25) and Ga in the form

of GaOx are important for the methanol

production rate and selectivity. Importantly, operando d-PDF and XAS

analyses of the catalysts under CO2 hydrogenation conditions

revealed that the fcc structure of the alloy and the oxidation states

of Ni and Ga remained invariant with respect to the activated state

(treated under H2), indicating that the bulk alloy was

not affected by the reaction conditions, in sharp contrast to what

has been observed for Cu–Ga and Pd–Ga. Furthermore,

monitoring the catalysts by operando DRIFTS indicates that the presence

of GaOx helps in stabilizing formate species,

an important reaction intermediate in the methanol formation pathway,

further supporting the importance of GaOx.

Overall, our results showed that alloy nanoparticles with a Ni:Ga ratio of 75:25 result in high methanol activity and selectivity—considerably higher than for Ni-richer alloys—while the presence of GaOx further increases the rate of methanol formation. These results pointed to the importance of site-isolation of Ni by Ga that leads to modifications of the electronic structure of Ni, viz., Niδ+Gaδ−. Ni site isolation likely prevents methanation activity, while the presence of GaOx further promotes the selective formation of methanol. Therefore, the regulation of the quantity of both alloyed Ga and GaOx species is crucial in achieving a high methanol selectivity and a high rate of methanol formation.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

All preparation and operations were performed in a M. Braun glovebox under an argon atmosphere or using high vacuum and standard Schlenk techniques. Pentane was purged with argon for 30 min and dried using a MB SPS 800 solvent purification system in which columns used for pentane purification were packed with activated copper and alumina. Benzene was either distilled from purple Na0/benzophenone or obtained from the MB SPS system and used without further purification. All solvents were stored over 4 Å molecular sieves after being transferred into a glovebox. Four Å molecular sieves were activated under high vacuum overnight at 300 °C. Fine quartz wool (Elemental Microanalysis) was calcined at 800 °C for 12 h and transferred into a glovebox for storage. SiO2–700 was prepared by heating Aerosil (200 m2/g) to 500 °C (ramp of 300 °C/h) in air and subsequent calcination in air for 12 h. Afterward, the material was evacuated at high vacuum (10–5 mbar) at 500 °C for 8 h, followed by heating to 700 °C (ramp of 60 °C/h) and keeping the material at 700 °C for approximately 24 h. Titration of SiO2–700 using [Mg(CH2Ph)2(THF)2] purified via sublimation prior to use yielded an Si–OH density of 0.3 mmol/g, corresponding to 0.9 accessible Si–OH groups per nm2. The molecular complexes [Ga(OSi(OtBu)3)3(THF)] and [Ni(CH3)2(tmeda)] were prepared according to adapted literature procedures.36,76 Other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Acros Organics and used as received. The supported species GaIII/SiO2 (precursor for NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 syntheses) were prepared according to an adapted literature procedure (see below).36

4.2. Synthesis of GaIII/SiO2

In a typical synthesis, SiO2–700 (0.729 g, 0.219 mmol −OH) was added to a 20 mL vial. Next, benzene (about 5 mL) was added slowly while stirring to give a white suspension. [Ga(OSi(OtBu)3)3(THF)] (0.147 mmol/g SiO2–700 nominal loading; 0.100 g, 0.107 mmol) was added slowly to the suspension as a white solution in benzene (about 5 mL) while stirring (1200 rpm). The resulting suspension was stirred at room temperature (rt) for 12 h (100 rpm). The benzene on top of the silica material was decanted, and the material was washed with benzene (5 mL) two times to wash off any unreacted complex. The material was then washed with pentane before it was dried in vacuo for 2 h to remove any residual solvent yielding GaIII/SiO2 as a white solid. The white material was then transferred into a tubular quartz reactor. The reactor was set under high vacuum (10–5 mbar) and successively heated to 300 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) for 1 h, 400 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) for 1 h, 500 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) for 1 h, and finally 600 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) for 10 h, yielding GaIII/SiO2 as a white/gray material.

4.3. Synthesis of Ga100/SiO2

Here, ca. 0.580 g of GaIII/SiO2 (synthesized as described above) was added to a tubular quartz flow-reactor supported with a porous quartz frit. The reactor was heated to 600 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) under a steady flow of H2 and then treated under H2 at 600 °C for 12 h. The reactor was subsequently evacuated under high vacuum (10–5 mbar) while cooling to room temperature, yielding Ga100/SiO2 as a white/gray material. Elemental analysis yielded: Ga, 0.88 wt %.

4.4. Synthesis of Ni100/SiO2

SiO2–700 (0.726 g, 0.218 mmol −OH) was added to a 20 mL vial. Benzene (about 5 mL) was added slowly while stirring to give a white suspension. [Ni(CH3)2(tmeda)] (0.342 mmol/g SiO2–700 nominal loading; 0.051 g, 0.248 mmol) was added slowly to the suspension as a deep yellow solution in benzene (about 5 mL) while stirring (1200 rpm), resulting in an immediate pink/deep-red coloration of SiO2. The resulting suspension was stirred at room temperature for 75 min (125 rpm) after which no yellow color of the supernatant was observable anymore. The benzene on top of the silica material was decanted, and the material was washed with benzene (5 mL) two times to wash off any unreacted complex. The material was then washed with pentane before it was dried in vacuo for 30 min to remove any residual solvent, yielding NiII/SiO2 as a pink/deep-red solid. The material was transferred to a tubular quartz flow-reactor supported with a porous quartz frit. The reactor was heated to 600 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) under a steady flow of H2 and held under H2 at 600 °C for 12 h. The reactor was subsequently evacuated under high vacuum (10–5 mbar) while cooling to room temperature, yielding Ni100/SiO2 as a dark brown/black material. Elemental analysis yielded: Ni, 2.12 wt %.

4.5. Synthesis of NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 (x = 65, 70, 75)

GaIII/SiO2 materials (0.700, 0.707, and 0.704 g) were synthesized as described above with different nominal Ga loadings (0.114, 0.147, and 0.184 mmol/g SiO2–700 nominal loading; 0.074, 0.097, and 0.121 g of [Ga(OSi(OtBu)3)3(THF)]). All materials were obtained as off white/gray materials. In a next step, the GaIII/SiO2 materials (0.640, 0.605, and 0.545 g) were added to 20 mL vials. Next, benzene (about 5 mL) was added slowly while stirring to give a grayish suspension. [Ni(CH3)2(tmeda)] (0.342 mmol/g GaIII/SiO2 nominal loading; 0.045, 0.042, and 0.038 g; 0.219, 0.207, and 0.187 mmol) was added slowly to the suspension as a deep yellow solution in benzene (about 5 mL) while stirring (1200 rpm), resulting in an immediate pink/deep-red coloration of the SiO2. The resulting suspensions were stirred at room temperature for 65 min (125 rpm) after which no yellow color of the supernatant was observable anymore. The benzene on top of the silica material was decanted, and the materials were washed with benzene (5 mL) two times to wash off any unreacted complex. The materials were then washed with pentane before they were dried in vacuo for ca. 45 min to remove any residual solvent yielding pink/deep-red solids. The materials were then transferred to small, tubular quartz vessels supported with a porous quartz frit. These small tubes were plugged with a small amount of quartz wool to avoid spilling. The small vessels were subsequently transferred to a large tubular quartz flow-reactor supported with a porous quartz frit. The reactor was heated to 600 °C (ramp of 5 °C/min) under a steady flow of H2 and then treated under H2 at 600 °C for 12 h. The reactor was subsequently evacuated under high vacuum (10–5 mbar) while cooling to room temperature, yielding Ni75Ga25/SiO2, Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 as dark brown/black materials.

The synthesis yielded ca. 500 mg per sample. The materials were characterized by elemental analysis, catalytic CO2 hydrogenation tests, in situ and operando X-ray total scattering, and operando DRIFTS. A second batch of Ni65Ga35/SiO2 and Ni75Ga25/SiO2 catalysts was prepared to allow for further characterization. The second catalyst batch was characterized by XAS (Figures 3, S32–44), ICP, catalytic tests (labeled with the suffix XAS). To ensure reproducibility, PDF was also collected for Ni65Ga35/SiO2-XAS.

4.6. Characterization

4.6.1. Elemental Analysis (Ga, Ni)

The elemental composition of the catalysts was determined by ICP-OES using an Agilent 5100 VDV instrument. Typically, 2–3 mg of the sample was dissolved in 5 mL of aqua regia, followed by microwave digestion at 175 °C for 30 min (Anton Paar, Multiwave GO). The resulting solution was cooled down to room temperature and diluted to 25 mL with deionized water. For the calibration of the instrument, a multielement standard (multielement standard solution 5, Sigma-Aldrich) was used. Each measurement was repeated three times, and the average values are reported in Table S1.

4.6.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

HAADF-STEM images were recorded on a FEI Talos F200X and–where indicated–a JEOL JEM-ARM300F Grand Arm “Vortex” instrument operated at 200 and 300 keV, respectively. Powdered samples were mixed in solid form with a Lacey-C 400 mesh Cu grid inside a glovebox under an Ar atmosphere before it was mounted onto a vacuum transfer tomography holder from Fischione Instruments (model #2560) (Talos) or a Double Tilt Atoms Defend Holder System (Mel-Build Corporation, serial number: DT-TR-006-J001) inside the glovebox, which was subsequently transferred to the chamber of the TEM in the absence of air. All imaging was done in air-free conditions if not indicated otherwise. For all materials, 300 nanoparticles were counted to yield a particle size distribution (PSD) analysis. The determination of the nanoparticle diameters for the PSD was done by manual measurements using the software ImageJ (version 1.52a). All values extracted from the specific particle size distributions assumed a normal distribution (most of the shown distribution curves are log-normal). The “±” symbol in the particle size distributions plots indicates the standard deviation of the mean particle size. The following catalysts were characterized by HAADF-STEM/EDX: Ni100/SiO2, Ni75Ga25/SiO2, Ni70Ga30/SiO2, and Ni65Ga35/SiO2 (as-prepared and after a CO2 hydrogenation test, the latter are referred to as “spent”).

4.6.3. Total X-ray Scattering and X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

In situ/operando X-ray total scattering and XAS experiments were performed at the beamlines ID15A and BM31 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, respectively. The same setup was used for both types of experiments, consisting of a capillary cell reactor (quartz capillary with an outer diameter of 1 and 0.02 mm wall thickness) containing ca. 2–3 mg of catalyst placed between two quartz wool plugs. Heating of the capillary was achieved from below via a hot air blower, and gases could be flown through it at a defined pressure via mass flow controllers and a backpressure regulator placed after the outlet of the capillary. A typical in situ/operando experiment consists of an in situ activation treatment (temperature ramp to 600 °C at 10 °C/min in 1 bar 5 mL/min H2 and then waiting for 1 h), cooling down to the reaction temperature of 230 °C in 1 bar 5 mL/min H2 (or 50 °C, to collect EXAFS, see Figure S18), and then pressurizing the reactor to 20 bar in 15 mL/min N2 (at 230 °C). Once the pressure had equilibrated, the gases were changed to the reaction gas mix of CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1 (at 20 bar, 5 mL/min). The off-gas during the reaction was analyzed using a compact gas chromatograph (Global Analyzer Solutions compact GC4.0 equipped with FID and TCD detectors, 1 injection/7 min).

X-ray total scattering data was collected continuously at a rate of 1 measurement/2.62 min and up to Qmax,instr = 30 Å–1 (incident X-ray energy of 90.0 keV). Total scattering data of the pristine silica support was measured under in situ activation and reaction conditions and used as background to calculate the d-PDF data of the NixGa(100–x)/SiO2 (Supporting Information Figure S22). In addition, total scattering data of the CeO2 NIST reference materials were obtained to determine the experimental resolution parameters Qdamp and Qbroad. For the conversion from total scattering data (reciprocal space) to the PDF (real space), the software PDFgetX377 v. 2.2.1 was used, whereas the modeling of the d-PDF was done in PDFGui78 v 1.0. The total scattering data was processed within the range Qmin = 1.5 Å-1 and Qmax = 23 Å-1 with rpoly = 1.0, which is approximately the r-limit for the maximum frequency in the F(Q) correction polynomial.

Ni and Ga K-edge XAS scans were collected consecutively. Ni and Ga XANES were collected between 8250 and 8550 eV and 10300–10600 eV, respectively, with a step of 0.3 eV (ca. 50 s/spectrum). Ni and Ga EXAFS were collected between 8200 and 8970 eV and 10200–11100 eV with a step of 0.5 eV (ca. 3 min/spectrum). More details on the X-ray total scattering and XAS data collection and processing can be found in section 3 of the Supporting Information.

4.6.4. Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy

Operando DRIFTS experiments were performed using a Nicolet 6700 FT-IR equipped with a Harrick Praying Mantis DRIFTS accessory and high-temperature reaction chamber. Data were collected from 650 to 4000 cm–1 at a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1 using a mercury cadmium telluride detector. In a typical experiment, ca. 20 mg of powder was placed onto a piece of quartz wool in the sample cup of the reaction cell. First, the catalysts were in situ activated in 15% H2/N2 (20 mL/min) at 590 °C (10°/min) for 1 h and subsequently cooled down to 230 °C. Next, the cell was pressurized to 20 bar in N2 (20 mL/min). Once the pressure had stabilized, a measurement was collected, which served as the background for all the subsequent measurements under reaction conditions. In a next step, the atmosphere was switched to CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1 (at 20 bar, 20 mL/min), and measurements were continuously collected every 1.3 min for ca. 2 h. The identical compact GC as the one used for the operando XAS/PDF experiments was used for the analysis of the off-gas. A blank test (empty reaction cell) was performed to determine the time needed for the equilibration of the feed gases from the time when the gases are switched from 20 bar N2 to the reaction gas mixture. The exchange time was approximately 126 min (see Figure S45).

4.7. Catalytic Tests

For the catalytic tests, 100 mg of the as-prepared powder was transferred into a Hastelloy C276 reactor tube (internal diameter 9.1 mm) inside a M. Braun glovebox under a N2 atmosphere. The powder was placed in between two pieces of quartz wool (Acros Organics, 9–30 μm) and onto a frit in the middle of the reactor tube (Hastelloy C276, pore size 2 μm). The reactor was then transferred from the glovebox and mounted into a Microactivity-Efficient flow reactor system (PID Eng & Tech), without exposing the catalyst to air (the reactor is provided with valves for such purpose). The spent catalysts were transferred back into the glovebox and stored for further TEM analysis.

The CO2 hydrogenation tests were performed as follows. First, the catalyst was heated to 600 °C (10 °C/min) in 1 bar H2 (50 mL/min) and held at 600 °C for 1 h. This step is referred to as in situ activation. Subsequently, the catalyst was cooled down to the reaction temperature of 230 °C (still in 1 bar H2, 50 mL/min), followed by a switch of the gas flow to 80 mL/min N2 and a pressure increase to 25 bar. After the stabilization of the pressure and temperature, the gas feed was switched to 25 bar of CO2:H2:N2 = 1:3:1 (100 mL/min, resulting in a GHSV of 60 L gcat–1 h–1), and the off-gas was continuously analyzed by a gas chromatograph (PerkinElmer Clarus 580 equipped with FID and TCD detectors, 1 injection/30 min). For further information on the catalytic tests, we refer the reader to Section 2 of the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant agreement No. 819573. N.K.Z. thanks the SINERGIA project (SNF Project No. CRSII5_183495) for financial support. L.R. thanks the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF project no. 200021_169134) for funding. This publication was created as part of NCCR Catalysis, a National Centre of Competence in Research funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 180544). Further, we would like to acknowledge the ETH grant ETH-18 22-1. The ESRF is acknowledged for the provision of beamtime (CH6215 and CH6136) and Dr. Dragos Stoian (SNBL) for invaluable support during XAS measurements. The authors thank Angelo Bellia, Alex Oing, David Niedbalka, Zixuan Chen, Matthias Becker, and Dr. Agnieszka Kierzkowska for support during the synchrotron experiments. Dr. Kierzkowska and Dr. Felix Donat are acknowledged for performing ICP-OES analysis. Dr. Wei Zhou is kindly acknowledged for the provision of the XAS data of GaIII/SiO2 and Ga-foil.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- d-PDF

differential (or difference) pair distribution function analysis

- DRIFTS

diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure

- fcc

face-centered cubic

- SOMC

surface organometallic chemistry

- STEM-EDX

scanning transmission electron microscopy–element-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- TMP

thermolytic molecular precursor

- TOS

time-on-stream

- XANES

X-ray absorption near-edge structure

- XAS

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.3c00677.

Experimental details, additional microscopy, X-ray absorption and IR spectroscopy, as well as X-ray total scattering/PDF and catalytic test data (PDF)

Author Contributions

CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy)79 was used for standardized contribution descriptions: N.K.Z.: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing (original draft), writing (review and editing). L.R.: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing (original draft), writing (review and editing). S.C.: investigation and methodology. P.M.A.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing). C.M.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing), resources, funding acquisition. C.C.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing), resources, funding acquisition. N.K.Z. and L.R. contributed equally to this work.

N.K.Z. thanks the SINERGIA project (SNSF project no. CRSII5_183495) for financial support. L.R. thanks the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF project no. 200021_169134) for funding. This publication was created as part of NCCR Catalysis (180544), a National Centre of Competence in Research funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. We acknowledge ESRF proposals CH-6136, CH-6215 (doi:10.15151/ESRF-ES-804825298), and CH-5884 (doi:10.15151/ESRF-ES-406702465). The authors acknowledge ETH foundation grant ETH-18 22-1. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant agreement No. 819573.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhong J.; Yang X.; Wu Z.; Liang B.; Huang Y.; Zhang T. State of the Art and Perspectives in Heterogeneous Catalysis of CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49 (5), 1385–1413. 10.1039/C9CS00614A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha F.; Han Z.; Tang S.; Wang J.; Li C. Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol over Non–Cu-Based Heterogeneous Catalysts. ChemSusChem 2020, 13 (23), 6160–6181. 10.1002/cssc.202002054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto G.; Zečević J.; Friedrich H.; de Jong K. P.; de Jongh P. E. Towards Stable Catalysts by Controlling Collective Properties of Supported Metal Nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12 (1), 34–39. 10.1038/nmat3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B.; Ma J.; Su X.; Yang C.; Duan H.; Zhou H.; Deng S.; Li L.; Huang Y. Investigation on Deactivation of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58 (21), 9030–9037. 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b01546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin O.; Pérez-Ramírez J. New and Revisited Insights into the Promotion of Methanol Synthesis Catalysts by CO2. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3 (12), 3343–3352. 10.1039/c3cy00573a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jangam A.; Hongmanorom P.; Hui Wai M.; Jeffry Poerjoto A.; Xi S.; Borgna A.; Kawi S. CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol over Partially Reduced Cu-SiO2P Catalysts: The Crucial Role of Hydroxyls for Methanol Selectivity. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4 (11), 12149–12162. 10.1021/acsaem.1c01734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao F.; Lo T. W. B.; Tsang S. C. E. Recent Developments in Palladium-Based Bimetallic Catalysts. ChemCatChem. 2015, 7 (14), 1998–2014. 10.1002/cctc.201500245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. M.-J.; Tsang S. C. E. Bimetallic Catalysts for Green Methanol Production via CO2 and Renewable Hydrogen: A Mini-Review and Prospects. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8 (14), 3450–3464. 10.1039/C8CY00304A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. W.; Luna M. L.; Berdunov N.; Wan W.; Kunze S.; Shaikhutdinov S.; Cuenya B. R. Unraveling Surface Structures of Gallium Promoted Transition Metal Catalysts in CO2 Hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14 (1), 4649. 10.1038/s41467-023-40361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfke J. L.; Tejeda-Serrano M.; Gani T. Z. H.; Rochlitz L.; Zhang S. B. X. Y.; Lin L.; Copéret C.; Safonova O. V.. Boundary Conditions for Promotion versus Poisoning in Copper-Gallium-based CO2–to–Methanol Hydrogenation Catalysts. ChemRxiv Submitted 2023–06–06. https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/647d9a52be16ad5c57800181 (accessed December 11, 2023), DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-47d99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina J. C.; Figueroa M.; Manrique R.; Pereira J. R.; Srinivasan P. D.; Bravo-Suárez J. J.; Medrano V. G. B.; Jiménez R.; Karelovic A. Catalytic Consequences of Ga Promotion on Cu for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7 (15), 3375–3387. 10.1039/C7CY01021D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E.; Noh G.; Wing Chan K.; Larmier K.; Lebedev D.; Searles K.; Wolf P.; Safonova O. V.; Copéret C. Enhanced CH3OH Selectivity in CO2 Hydrogenation Using Cu-Based Catalysts Generated via SOMC from Ga III Single-Sites. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (29), 7593–7598. 10.1039/D0SC00465K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studt F.; Sharafutdinov I.; Abild-Pedersen F.; Elkjær C. F.; Hummelsho̷j J. S.; Dahl S.; Chorkendorff I.; No̷rskov J. K. Discovery of a Ni-Ga Catalyst for Carbon Dioxide Reduction to Methanol. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6 (4), 320–324. 10.1038/nchem.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo A.; Snider J. L.; Sokaras D.; Nordlund D.; Kroll T.; Ogasawara H.; Kovarik L.; Duyar M. S.; Jaramillo T. F. Ni5Ga3 Catalysts for CO2 Reduction to Methanol: Exploring the Role of Ga Surface Oxidation/Reduction on Catalytic Activity. Appl. Catal., B 2020, 267, 118369 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.; Ji W.; Russell C. K.; Zhang Y.; Fan M.; Shen Z. A New and Different Insight into the Promotion Mechanisms of Ga for the Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol over a Ga-Doped Ni(211) Bimetallic Catalyst. Nanoscale 2019, 11 (20), 9969–9979. 10.1039/C9NR01245A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafutdinov I.; Elkjær C. F.; Pereira de Carvalho H. W.; Gardini D.; Chiarello G. L.; Damsgaard C. D.; Wagner J. B.; Grunwaldt J.-D.; Dahl S.; Chorkendorff I. Intermetallic Compounds of Ni and Ga as Catalysts for the Synthesis of Methanol. J. Catal. 2014, 320, 77–88. 10.1016/j.jcat.2014.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.; Oh S.; Trung Tran S. B.; Park J. Y. Size-Controlled Model Ni Catalysts on Ga2O3 for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. J. Catal. 2019, 376, 68–76. 10.1016/j.jcat.2019.06.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty S. R.; Phongprueksathat N.; Lam E.; Noh G.; Safonova O. V.; Urakawa A.; Copéret C. Silica-Supported PdGa Nanoparticles: Metal Synergy for Highly Active and Selective CO2-to-CH3OH Hydrogenation. JACS Au 2021, 1 (4), 450–458. 10.1021/jacsau.1c00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. E.; Delgado J. J.; Mira C.; Calvino J. J.; Bernal S.; Chiavassa D. L.; Baltanas M. A.; Bonivardi A. L. The Role of Pd-Ga Bimetallic Particles in the Bifunctional Mechanism of Selective Methanol Synthesis via CO2 Hydrogenation on a Pd/Ga2O3 Catalyst. J. Catal. 2012, 292, 90–98. 10.1016/j.jcat.2012.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiordaliso E. M.; Sharafutdinov I.; Carvalho H. W. P.; Grunwaldt J.-D.; Hansen T. W.; Chorkendorff I.; Wagner J. B.; Damsgaard C. D. Intermetallic GaPd2 Nanoparticles on SiO2for Low-Pressure CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol: Catalytic Performance and In Situ Characterization. ACS Catal. 2015, 5 (10), 5827–5836. 10.1021/acscatal.5b01271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Trenco A.; White E. R.; Regoutz A.; Payne D. J.; Shaffer M. S. P.; Williams C. K. Pd2Ga-Based Colloids as Highly Active Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol. ACS Catal. 2017, 7 (2), 1186–1196. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]