Graphical abstract

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Aryl fluorosulfate, Sulfur (VI) fluoride exchange, Structure–activity relationship studies, Anti-TB activity, Pharmacokinetic, SuFEx

Abstract

To identify new compounds that can effectively inhibit Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), we screened, synthesized, and evaluated a series of novel aryl fluorosulfate derivatives for their in vitro inhibitory activity against Mtb. Compound 21b exhibited an in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.06 µM against Mtb, no cytotoxicity against both HEK293T and HepG2 mammalian cell lines, and had good in vivo mouse plasma exposure and lung concentration with a 20 mg/kg oral dose, which supports advanced development as a new chemical entity for TB treatment.

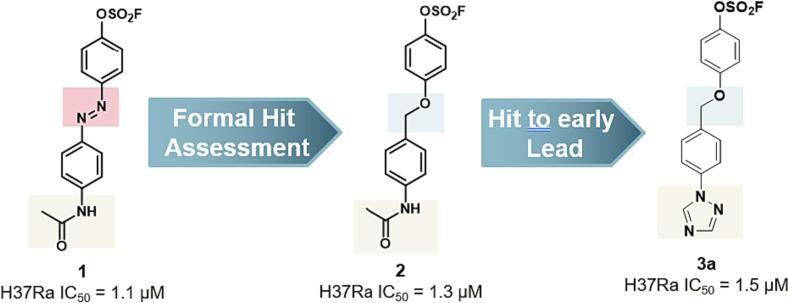

Before the COVID-19 global pandemic, tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), was the leading cause of death due to a single infectious agent.1 People with TB need take multiple drug combo for standard 6 month, or even up to 2 years or longer for multi- and extensive-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB/XDR-TB). The rising emergence of MDR-TB/XDR-TB is one of the most relevant public health problems worldwide.1, 2 For these reasons, there is an unmet medical need to deliver new drug candidates to expand the TB drug development pipeline and to shorten the treatment period. Click chemistry of sulfur (VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEx) groups, developed by Sharpless and coworkers,3 has been successfully introduced into many bioactive molecules in chemical biology and drug discovery, especially as a covalently binding warhead.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However, the application of SuFEx as anti-TB agents has not been reported. Working with the Sharpless group, we discovered that aryl fluorosulfate 1 with a diazo linker has good anti-TB activity with an IC50 = 1.1 µM from screening of a small library of 406 SuFEx compounds against Mtb in the attenuated lab H37Ra strain.

To address the photolabile issue of the diazo linker,9 we carried out a formal hit assessment, exploring multiple linkers including amide, 1,2,3-triazole, olefin, and ether. While most of these linkers were much less active or inactive than compound 1, phenyl ether compound 2 exhibited comparable activity (H37Ra IC50 = 1.3 µM). We then performed further hit-to-lead optimization of compound 2 focusing on replacement of the metabolically labile amide tail and generated the N1-1,2,4-triazole-containing early lead 3a, which shows only slightly decreased activity (H37Ra IC50 = 1.5 µM) (Fig. 1). Encouraged by these results, we conducted lead optimization of compound 3a via detailed structure − activity relationship (SAR) studies, as described in this paper. The SAR campaign led to compound 21b with good anti-TB activity (H37Rv MIC = 0.06 µM) and favorable pharmacokinetic (PK) properties for further preclinical development.

Fig. 1.

Hit to early lead 3a from screening hit 1.

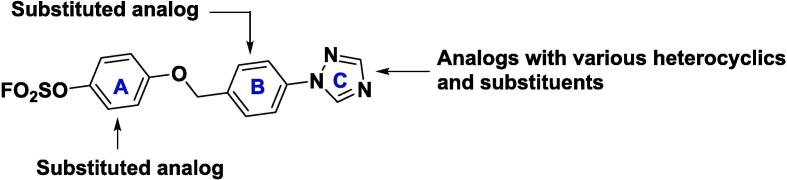

We explored the SAR of the initial lead 3a in three regions (Fig. 2). The general synthesis of aryl fluorosulfates started from a conversion of commercially available (4-bromophenyl)methanol derivatives (4) to 1-bromo-4-(chloromethyl)benzenes (5), followed by phenyl ether formation with methoxymethyl (MOM)-protected hydroquinones (6). After Buchwald amination with the corresponding triazoles (8), MOM was removed under an acidic condition. The resulting phenol (10) was converted to the desired aryl fluorosulfate 3a and their analogs by sulfuryl fluoride (SO2F2) gas or a shelf-stable SuFEx reagent, 4-(acetylamino)phenyl]imidodisulfuryl difluoride (AISF),10 under a basic condition.

Fig. 2.

Chemical structure of aryl fluorosulfate 3a and its derivatization for the SAR study.

A focused library of western phenyl (A) and middle phenyl (B) modified analogs was synthesized and evaluated for antitubercular activity by H37Rv MIC or CDC1551 IC90 (Table 1). The cytotoxicity against both HEK293T and HepG2 mammalian cells was also examined. Our early lead 3a has moderate anti-TB activity with H37Rv MIC = 2.84 µM and CDC1551 IC90 = 4.71 µM. The substitution SAR on the western phenyl ring revealed that a methoxy (OMe) group at the ortho position to the SuFEx group is not tolerated: compounds 3b was not active against Mtb. Replacement with a chloro group gave compound 3c with similar activity to 3a against CDC1551; however, 3c exhibited cytotoxicity against HEK293T and HepG2 cell lines. Next, we turned our attention to middle phenyl modification. We began by testing mono-fluorinated and di-fluorinated analogs (3d-3i) against Mtb. In general, fluorination at the meta position to triazole increased potency: both 3d and 3i showed 4-fold increases in H37Rv MIC. While difluorinated analog 3i showed moderate cytotoxicity against HepG2 (IC50 = 5.8 µM), it still had good selectivity index (SI = 9.6). Changing one fluoro to a more electron-deficient nitrile group gave compound 3j with much decreased potency (MIC = 5.0 µM).

Table 1.

| Compound | Phenyl A | Phenyl B | Anti-TB activity |

Cytotoxicity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H37Rv MIC (µM) | CDC1551 IC90 (µM) | HEK293T CC50 (µM) | HepG2 CC50 (µM) | |||

| 3a |  |

|

2.84 | 4.71 | 11.6 | 19.3 |

| 3b |  |

|

25 | >30 | >40 | 13.3 |

| 3c |  |

|

ND | 4.64 | 3.7 | 5.8 |

| 3d |  |

|

0.6 | 1.3 | 22.7 | 12.5 |

| 3e |  |

|

2.5 | ND | 16.8 | 17.6 |

| 3f |  |

|

1.25 | ND | 18.8 | 22.4 |

| 3 g |  |

|

10 | ND | 34.8 | >40 |

| 3 h |  |

|

1.25 | ND | 21.6 | 29.5 |

| 3i |  |

|

0.6 | ND | >40 | 5.8 |

| 3j |  |

|

5 | ND | >40 | >40 |

ND = not determined.

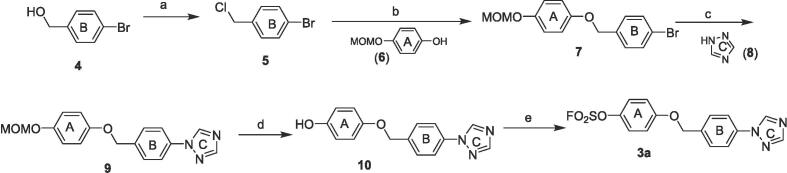

In the context of difluoro-substituted phenyl, we further examined the activity of isomeric triazoles and other 5-membered heterocycles (Table 2). Analogs 3 k-3 m were made with a general route shown in Scheme 1. Compounds 19a-19j were synthesized using a modified procedure (Scheme 2) or using procedures described in supporting document. Using a similar procedure as in Scheme 1, phenol ether 14 was obtained, then phenyl bromide was transformed into phenyl boronic ester 15. The following Suzuki coupling was used to install 5-membered heterocycles as exemplified by a trimethylsilylethoxymethyl (SEM)-protected triazole 16. The subsequent SuFEx installation followed by SEM removal gave desired fluorosulfates 19a and related analogs.

Table 2.

| Compound | Heterocyclic ring C | Anti-TB activity |

Cytotoxicity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H37Rv MIC (µM) | HEK293T CC50 µM) | HepG2 CC50 (µM) | ||

| 3i |  |

0.6 | >40 | 5.8 |

| 3 k |  |

1.23 | >40 | >40 |

| 3 l |  |

0.16 | 27.7 | 17.0 |

| 3 m |  |

0.22 | >40 | >40 |

| 19a |  |

0.9 | 14.7 | 19.3 |

| 19b |  |

1.25 | ND | >40 |

| 19c |  |

0.84 | 31.7 | 18.5 |

| 19d |  |

0.3 | >40 | 30.14 |

| 19e |  |

1.25 | 26.0 | 13.7 |

| 19f |  |

0.37 | 9.65 | 8.63 |

| 19 g |  |

0.45 | 13.2 | 12.1 |

| 19 h |  |

5 | >40 | >40 |

| 19i |  |

0.62 | >40 | >40 |

| 19j |  |

0.78 | 23.8 | 6.99 |

Scheme 1.

General synthetic route. Reagents and conditions: a) SOCl2, DMF/DCM, rt, 2 h; b) 6, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 12 h; c) 8, Pd2(dba)3, Me4-tBu-X-Phos, Cs2CO3, toluene, 100 °C, 5 h; d) Formic acid, DCM, rt, 2 h; e) SO2F2, TEA, DCM, rt, 30 min; or AISF, DBU, THF, 0 °C, 30 min.

Scheme 2.

General synthetic route for compounds 19a-19j: a) SOCl2, DMF/DCM, rt, 2 h; b) 13, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 5 h; c) Pin2B2, Pd(dppf)Cl2, KOAc, dioxane, 100 °C, 2 h; d) SEMCl, TEA, DCM, rt, 12 h; e) 16, Pd(dppf)Cl2, K3PO4, dioxane/H2O, 80 °C, 2 h; f) AISF, DBU, THF, rt, 30 min; g) TFA, DCM, rt, 1 h.

Among isomeric triazoles, N2-1,2,3 triazole analog 3 k showed 2-fold decreased activity, and N1-1,2,3 triaozle 3 l and N1-1,3,4-triazole 3 m had 3-fold increases in MIC. 4H-1,2,4-triazole analog 19a had an MIC < 1.0 µM. We also synthesized other 5-membered heterocyclic analogs including pyrazole 19c, imidazole 19d and 19f, and tetrazole 19 g and 19 h, and evaluated them for anti-TB activity. Some corresponding nitrogen-substituted methyl analogs, including 19b and 19e were also prepared. In general, these compounds had low activity compared to triazole analogs. In addition, oxadiazole 19i and isoxazole 19j were made and they exhibited MIC < 1 µM against Mtb. All analogs had good cytotoxicity profiles in HEK293T and HepG2 cell lines, except one imidazole analog 19f that had a half maximal cellular cytotoxicity concentration 50 (CC50) < 10 µM.

We further examined the substitution effect with the N1-1,2,4- triazole system (Table 3). Most compounds were prepared with a general synthetic method as outlined in Scheme 1. 3-Methyl-substituted analog 20a showed 2-fold increased potency, while ethyl- and isopropyl-substituted analogs 20b and 20c retained similar potency. The introduction of a more steric t-butyl (20d) resulted in 2-fold decreased activity with MIC = 1.2 µM.

Table 3.

| compound | R1 | R2 | Anti-TB activity |

Cytotoxicity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H37Rv MIC (µM) | HEK293T CC50 (µM) | HepG2 CC50 (µM) | |||

| 3i | H | H | 0.6 | >40 | 5.8 |

| 20a | H | Me | 0.3 | 17.1 | 16.3 |

| 20b | H | Et | 0.6 | >40 | 5.8 |

| 20c | H | iPr | 0.6 | 16.7 | 12.4 |

| 20d | H | tBu | 1.2 | 13.7 | 6.9 |

| 20e | Me | Me | 0.23 | 14.3 | 8.1 |

| 20f | H | OMe | 0.6 | >40 | >40 |

| 20 g | H | CN | 0.45 | ND | 10.3 |

| 20 h | H | N(Me)2 | 0.31 | >40 | >40 |

| 20i | H | SO2Me | 0.40 | 17.2 | 9.3 |

| 20j | H | COOH | 1.25 | >40 | >40 |

| 20 k | H | CONH2 | 0.17 | >40 | >40 |

| 21a | H | NHCOMe | 0.15 | >40 | >40 |

| 21b | H | NHSO2Me | 0.06 | >40 | >40 |

| 20 l | H | SONH2 | 0.47 | ND | >40 |

| 21c | H | N(Me)SO2Me | 0.31 | ND | 15.3 |

| 21d | H | NHSO2Et | 0.08 | ND | >40 |

| 21e | H | NHSO2iPr | 0.31 | >40 | >40 |

| 21f | H | NHSO2tBu | 2.5 | >40 | >40 |

We then synthesized 3,5-dimethyl analog disubstituted analog (20e), which had similar potency to 3-mono methyl analog 20a. We also investigated an electronic effect by introducing electronic donating substituent methoxy (20f), and electronic withdrawing nitrile (20 g). Both showed similar activity to non-substituted analog 3i. Dimethyl amine and methyl sulfone substituted triazole analogs 20 h and 20i had slightly improved activity. The addition of COOH showed low activity with MIC = 1.25 µM (20j).

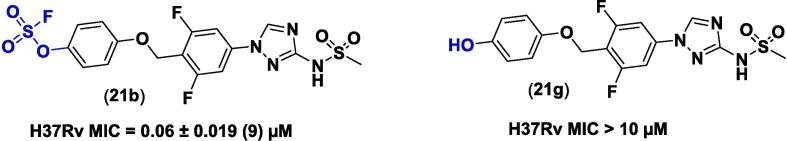

Encouraged by these results, we explored further fine tuning with steric and electronic effects. Introduction of acetamide gave compound 20 k a 4-fold increased anti-TB activity with MIC = 0.17 µM. The methyl amide analog 21a had a similar potency. We observed further improved activity with the methyl sulfonamide-substituted analog 21b which had an MIC = 0.06 µM and a 47-fold improvement in anti-TB activity compared to our initial lead 3a. Compound 21b showed no cytotoxicity against both HEK293T and HepG2 cell lines. We also conducted additional SAR around sulfonamide. The reversed sulfonamide analog 20 l had much lower activity than 21b. The N-methyl substituted analog 21c, also had 4-fold decreased activity compared to 21b, suggesting the free NH is needed for high potency. Exchanging methyl for ethyl in analog 21d provided similar potency. However, isopropyl and tertbutyl sulfonamide 21e and 21f had much lower anti-TB activity, with 21f having a MIC = 2.5 µM. Compound 21 g, the phenol version of compound 21b, showed no activity in H37Rv MIC (Fig. 3), which confirmed that SuFEx group is essential for anti-TB activity.

Fig. 3.

SuFEx is essential for anti-TB activity.

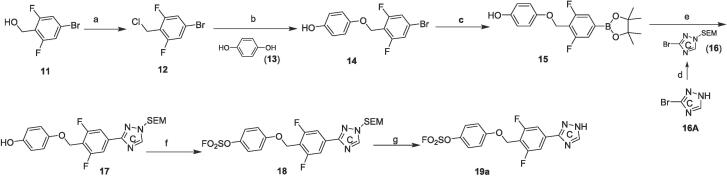

The synthesis of methyl sulfonamide-substituted analog 21b was shown in Scheme 3. A optimized condition of step b, Chan-Lam Coupling,11 was used for the reaction of 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole 24 with tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) protected phenyl boronic ester 23. The following hydrogenation (step c), TBDMS removal by tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) (step d) and SuFEx installation with ASIF (step e) gave amino triazole 28. The reaction of 28 with methylsulfonyl chloride gave di-substituted analog 29. Subsequent treatment with TBAF provided desired sulfonamide 21b.

Scheme 3.

Synthetic route for compound 21b: a) Pin2B2, Pd(dppf)Cl2, KOAc, dioxane, 100 °C, 2 h; b) 24, Cu(OAc)2, pyridine, boric acid, CH3CN, 90 °C, 4 h; c) Pd/C, H2, THF; d) TABF, THF,0 °C - rt, 1 h; e) AISF, DBU, THF, 0 °C, 30 min; f) MeSO2Cl, TEA, DCM, 0 °C -rt, 1 h; g) TBAF, THF, 0 °C, 30 min.

With compound 21b exhibiting good in vitro anti-TB activity and clean cytotoxicity profile, we next checked its PK properties. 21b was administered to mice using both oral (PO) and intravenous (IV) routes at 20 mg/kg and 3 mg/kg in 75 % PEG/25 % D5W solution, respectively. In the PO arm, in addition to plasma sampling, we also examined compound residence in lung at 8 and 24 h post-dosing with consideration for TB treatment. Overall, compound 21b showed good oral plasma exposure with excellent bioavailability (F = 99.4 %; Table 4). The 20 mg/kg PO dose achieved a near 24 h coverage of plasma and lung levels above the H37Rv MIC (MIC = 0.06 µM = 28 ng/mL) (Table 4). We further checked both mouse plasma and lung protein binding of 21b: the unbound levels were 0.8 % and 1.6 %, respectively. As a result, the unbound levels of plasma and lung coverage over MIC were near 8 h at 20 mg/kg PO. These PK results supported advancing compound 21b into a TB efficacy mouse model.

Table 4.

Mouse PO/IV PK results of compound 21b.

| route | Dose (mg/kg) | Formulation | Cmax (ng/mL) | Tmax (hr) | T1/2 (hr) | Cl (mL/min/kg) | Vd (L/kg) | AUC0-24 (hr*ng/mL) | F (%) | Cplasma at 8 h (ng/mL) | Clung at 8 h (ng/mL) | Cplasma at 24 h (ng/mL) | Clung at 24 h (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO | 20 | 75 %PEG/25 % D5W solution | 9,290 | 1.00 | 2.57 | ND | ND | 47,615 | 99.4 | 2,120 | 1,596 | 22.6 | 14.1 |

| IV | 3 | 3,314 (C0) | – | 3.93 | 7.05 | 2.38 | 7,085 | – | – | – | – | – |

In conclusion, we developed a new class of arylfluorosulfate compounds with good in vitro activity against Mtb. Current lead 21b has 0.06 µM H37Rv MIC, clean cytotoxicity profile and good mouse in vivo exposure. These aryl fluorosulfates added a novel chemotype for future evaluation in the TB drug development pipeline. We are performing detailed mechanism of action and efficacy studies, results which will be reported in due course.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Calibr pharmacology group, especially Drs. Ashley Woods, Victor Chi, Van Nguyen-Tran, Kyoung-Jin Lee, Shuangwei Li, and Sean Joseph for their assistance with the project. We thank Drs. Hua Wang and Jiajia Dong for helpful discussions regarding SuFEx. Special thanks to Dr. Kit Bonin for his assistance in manuscript preparation. This work was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation #OPP1107194 and #OPP1208899 to Calibr.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2023.129596.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.WHO, Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/globaltuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022 Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- 2.Günthe G. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a review of current concepts and future challenges. Clin Med J. 2014;14:185–279. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-3-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong J., Sharpless K.B., Kwisnek L., Oakdale J.S., Fokin V.V. SuFEx-based synthesis of polysulfates. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9466–9470. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W., Dong J., Plate L., et al. Arylfluorosulfates inactivate intracellular lipid binding protein(s) through chemoselective SuFEx reaction with a binding site Tyr residue. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:7353–7364. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadeyi O.O., Hoth L.R., Choi C., et al. Covalent enzyme inhibition through fluorosulfate modification of a noncatalytic serine residue. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:2015–2020. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones L.H. Emerging utility of fluorosulfate chemical probes. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2018;9:584–586. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Q., Woehl J.L., Kitamura S., et al. SuFEx-enabled, agnostic discovery of covalent inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:18808–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1909972116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolding J.E., Martín-Gago P., Rajabi N., et al. Aryl fluorosulfate based inhibitors that covalently target the SIRT5 lysine deacylase. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202204565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.S. Patai. The chemistry of the hydrazo, azo and azoxy groups. PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Son, 1997. DOI:10.1002/0470023503.

- 10.Zhou H., Mukherjee P., Liu R., et al. Introduction of a crystalline, shelf-stable reagent for the synthesis of sulfur(VI) fluorides. Org Lett. 2018;20:812–815. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao K.S., Wu T.S. Chan-Lam coupling reactions: synthesis of heterocycles. Tetrahedron. 2012;38:7735–7754. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2012.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.