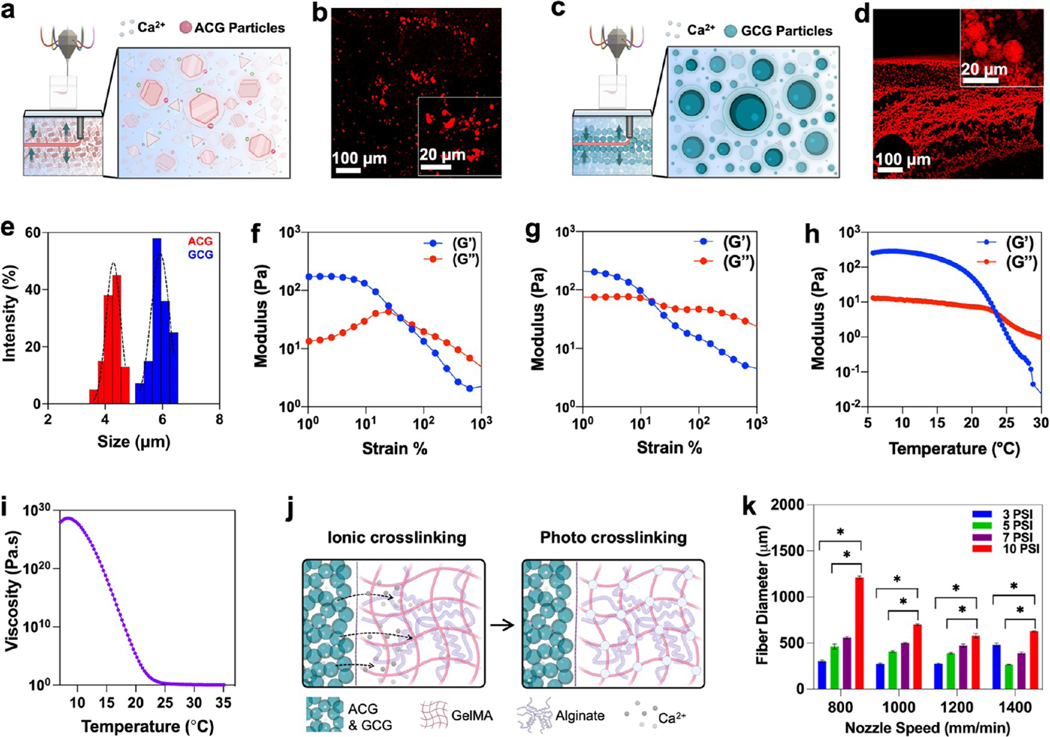

Figure 2.

Characterization of CGs as a supporting bath and bioink. (a–d) Schematics showing self-healing and various molecular interactions such as ionic and hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonding in (a) agarose colloidal gel (ACG) particles and (c) gelatin colloidal gel (GCG) particles. Fluorescent images of rhodamine incubated (b) ACG and (d) GCG. (e) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) size analysis of ACG and GCG particles. (f, g) Change in storage (G′) and loss moduli (G″) of the ACG and GCGs when stress is applied at a rate of 1–100–S, respectively. (h) Storage (G′) and loss moduli (G″) change in the 3% alginate–7% GelMA blend bioinks as a factor of temperature, suggesting a sol–gel transition. (i) Complex viscosity of the 3% alginate–7% GelMA blend bioink as a function of temperature. (j) Schematics showing two stages of cross-linking of alginate–GelMA blend bioinks; ionic cross-linking was achieved for alginate groups using Ca2+ ions and photo-cross-linking was achieved for the GelMA component of the bioink using excitation of photoinitiators. (k) Fiber diameter of the 3% alginate–7% GelMA blend bioink in GCG as a function of applied pressure and nozzle speed (n = 3; *p < 0.05).