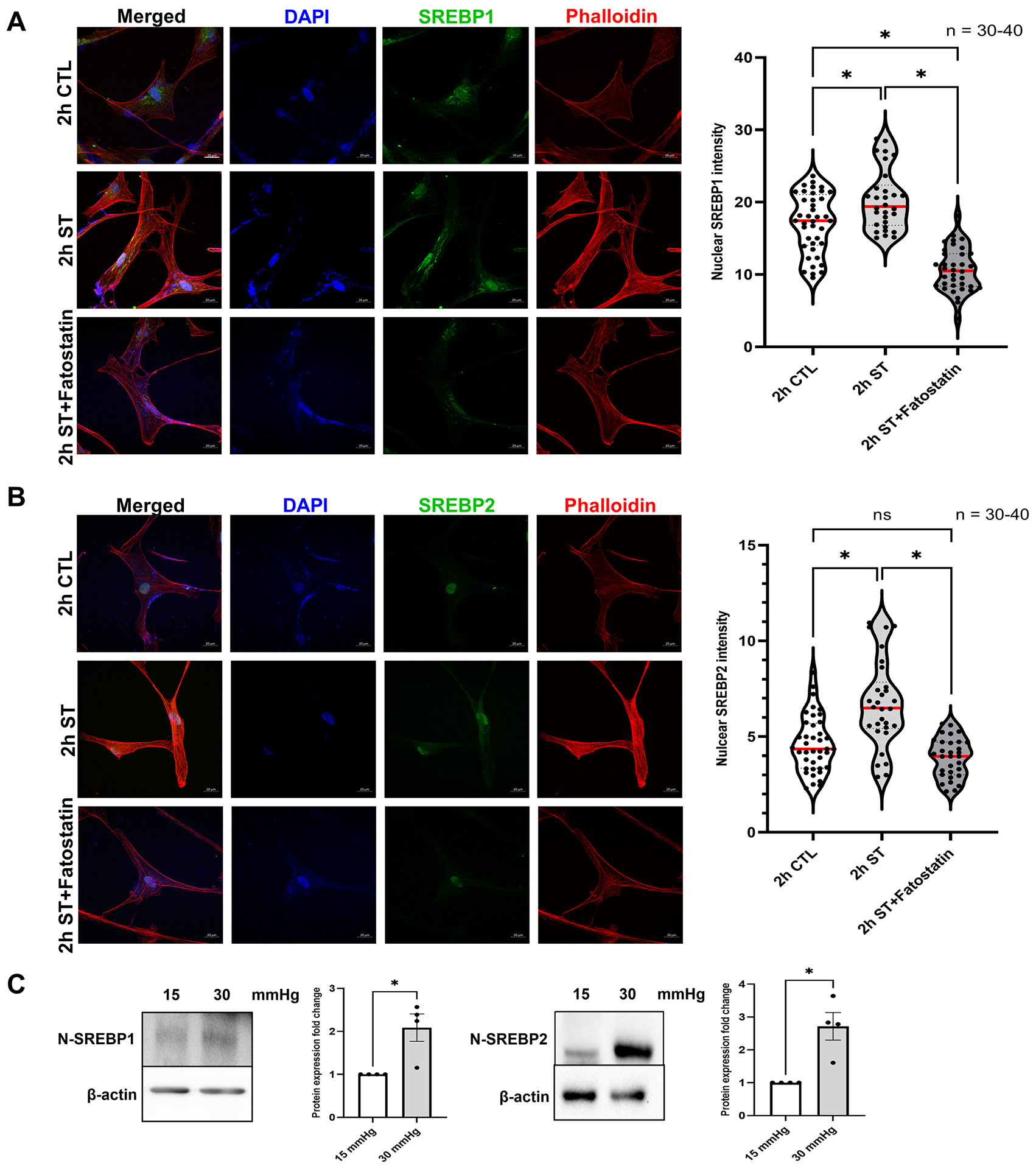

Fig. 1: Mechanical stress on trabecular meshwork induces SREBPs activation.

(A) and (B) Localization of SREBPs in HTM cells subjected to cyclic mechanical stretch was checked using immunofluorescence (IF). After 2 h of mechanical stress, HTM cells show a strong nuclear localization of both SREBP1 and SREBP2 (second-row third column). Phalloidin was used to stain the distribution of filamentous actin (F-actin) fiber in the cells. After 2 h of mechanical stress, there was increased F-actin distribution inside the HTM cells (second-row fourth column). 2 h stretch combined with fatostatin treatment shows decreased nuclear localization of both SREBP1 and SREBP2 (third-row third column) and decreased F-actin distribution inside the HTM cells (third-row fourth column). Quantification of immunofluorescence images using ImageJ-based fluorescence intensity measurements shows a significant increase in both nuclear SREBP1 and nuclear SREBP2 mean fluorescence intensity in 2 h stretched HTM cells and a significant decrease in 2 h stretch combined with fatostatin treatment (right panel). The nucleus was stained with DAPI in blue. Images were captured in z-stack in a confocal microscope, and stacks were orthogonally projected. Scale bar 20 micron. (C) Protein expression of both nuclear form SREBP1 (N-SREBP1) and SREBP2 (N-SREBP2) was significantly increased in TM derived from enucleated porcine anterior segments perfused under the elevated pressure of 30 mmHg for 5 h compared with 15 mmHg. The results were based on semi-quantitative immunoblotting with subsequent densitometric analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. Values represent the mean ± SEM, where n = 4–40 (including biological replicates and experimental replicates). *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. CTL: un-stretched control HTM cells, ST: stretched HTM cells.