Abstract

In humans, social participation and integration wane with advanced age, a pattern hypothesized to stem from cognitive or physical decrements. Similar age-related decreases in social participation have been observed in several nonhuman primate species. Here, we investigated cross-sectional age-related associations between social interactions, activity patterns, and cognitive function in 25 group-living female vervets (a.k.a. African green monkeys, Chlorocebus sabaeus) aged 8–29 years. Time spent in affiliative behavior decreased with age, and time spent alone correspondingly increased. Furthermore, time spent grooming others decreased with age, but the amount of grooming received did not. The number of social partners to whom individuals directed grooming also decreased with age. Grooming patterns mirrored physical activity levels, which also decreased with age. The relationship between age and grooming time was mediated, in part, by cognitive performance. Specifically, executive function significantly mediated age’s effect on time spent in grooming interactions. In contrast, we did not find evidence that physical performance mediated age-related variation in social participation. Taken together, our results suggest that aging female vervets were not socially excluded but decreasingly engaged in social behavior, and that cognitive deficits may underlie this relationship.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-023-00820-7.

Keywords: Aging, Cognition, Nonhuman primates, Physical function, Social integration

Introduction

In many high-income societies, social integration wanes with age [1]. Older adults may exhibit lower levels of social participation [2], engage a smaller number of social partners [3], and spend more time alone [4]. These age-related changes, collectively known as social aging, become detrimental when they precipitate social isolation, an ever-growing public health concern [5]. Social isolation and associated loneliness are linked to impaired physical and mental health [6] and predict all-cause mortality [1, 7]. Consequently, understanding factors and processes contributing to social integration will help inform interventions that mitigate the deleterious effects of social isolation.

Numerous factors may contribute to aging-related changes in social behavior, including geographic separation from friends and family, changes in lifestyle (e.g., retirement), death of social partners, and reduction in resources that support social interaction. Importantly, social aging may also stem from functional impairments in other biological systems. Declining cognitive performance is hypothesized to drive social aging, as functional declines in cognition are associated with decreased social participation and increased social isolation [8–11]. The causal direction of this association remains unclear, as social isolation has been observed to precede impairments in memory [12, 13] and general cognitive performance [14, 15].

Decline in physical performance plays a role in decreased social integration among aging individuals. Diminishing physical capabilities—e.g., declines in endurance, strength, and coordination [16]—accompany aging [17]. Furthermore, physical performance and activity levels have been linked to social integration in various populations [18–20]. Impaired mobility, physical frailty, pain, reductions in processing speed, and visual impairment may discourage social participation [21–25]. Some aspects of social behavior may be unrelated to physical function. For example, in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging, associations were reported between physical performance and loneliness, living alone, and reduced frequency of community activities. However, low social contact based on self-reported frequency of social interactions of almost any kind (phone, email, etc.) with family and friends was unrelated to physical performance [19].

Nonhuman primates (NHPs) provide excellent models in which to study mechanisms of social aging in humans due to their evolutionary proximity to humans, long lifespans, and complex social relationships and behaviors. Importantly, NHPs are not believed to understand the inevitability of mortality [26], nor are their decisions driven by financial constraints or obligations. Consequently, aging patterns that other primates share with humans likely represent shared biological mechanisms.

There is ample evidence from both captive and wild populations that NHPs exhibit changes in social engagement—indicated primarily via engagement in dyadic grooming interactions—that may recapitulate social aging in humans. In long-tailed macaques (a.k.a. cynomolgus macaques, Macaca fascicularis), older females engaged in less grooming, an effect that was further exacerbated by low social status [27]. In semi-captive barbary macaques (M. sylvanus), both males and females of older ages exhibited lower levels of social and physical activity [28]. Furthermore, among females, older individuals were approached by fewer social partners, and initiated fewer social interactions than younger females [28]. Compared to their younger adult counterparts, older wild male chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) engage with fewer social partners and focus on a smaller number of strong social bonds [29]. Likewise, older captive tufted capuchins (Sapajus sp.), groomed others less (particularly females), received less grooming, and showed greater preference for particular grooming partners [30]. Older stumptail (M. arctoides) and Japanese macaque (M. fuscata) females were less socially and physically active than younger females [31]. However, older females were not excluded from social interactions; rather, older females more often avoided social partners, consistent with the hypothesis that physiological deterioration may underlie social withdrawal [31].

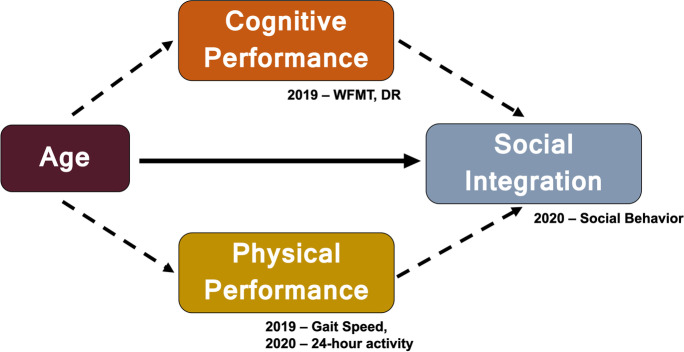

In the present study, we investigated whether female vervets (Chlorocebus sabaeus, also known as African green monkeys) exhibit age-related variation in social behavior comparable to human social aging, and whether social aging can be attributed to functional decline in other systems. Vervets are well-characterized models of several aging-related conditions, including reproductive senescence [32, 33], cardiovascular disease [34], type-two diabetes [35], and gastrointestinal barrier dysfunction [36]. Critically, members of this species exhibit human-like patterns of increasing cognitive and physical impairments associated with aging [37, 38] (see Frye, Craft et al. [37] for review). Here, we first characterized age-related variation in social behavior, cognitive ability, and physical performance (gait speed and 24-h activity levels). Our group has previously demonstrated that vervets exhibit notable, age-related, interrelated variation in both cognitive and physical performance [38]; we replicate these findings here. We then examined the degree to which cognitive and/or physical performance accounted for relationships between age and social behavior using mediation analysis [39] to test two competing (although not mutually exclusive) hypotheses: (1) that cognitive decrements precipitate social aging and (2) that physical performance precipitates social aging (Fig. 1). Our study has several key strengths including an NHP study population of various ages living in naturalistic social groups, and collection of corresponding social, physical, and cognitive data on the same individuals over a relatively short time period.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of potential mediation effects of cognitive and physical performance on social integration in aging female vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus). Numbers indicate the year in which data for each variable were collected

Methods

Ethical approvals

This work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wake Forest University School of Medicine. Experimental procedures complied with National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as well as state and federal laws.

Subjects

We studied 25 adult female vervets ages 8 to 29 years at the time of social behavior observations, which ranges from middle age to the most elderly. The number of individuals grouped by age range is listed in Table 1. Study subjects were embedded in ten matrilineal social groups in the Vervet Research Colony (VRC) at Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, NC), detailed accounts of which have been published [33, 37, 38, 40, 41]. The VRC includes approximately 300 monkeys that range in age from newborn to ~ 30 years, born and mother-reared in social groups managed to reflect free-living population demographics. They are housed in enclosures which include outdoor (approximately 1000 ft2) and indoor (approximately 300 ft2) space providing ample opportunity for three-dimensional physical activity and social engagement. Monkey chow (LabDiet) and water is available ad libitum, and health is monitored daily by veterinary and VRC staff. All procedures were conducted in accordance with state and federal laws, standards of the Department of Health and Human Services, and guidelines established by the Wake Forest Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table 1.

Age ranges of individual vervets included in the study

| Age (years) | < 10 | 10–15 | 15–21 | 21–25 | > 25 |

| Number of individuals | 1 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

Social behavior observations

Social behavior was recorded in 6, 10-min focal animal observations/subject (25 h total) between June and September 2020 [42]. During observations, we measured the duration of all affiliative social interactions, including time spent in body contact and physical proximity (within arm’s reach) to conspecifics and the amount of time being groomed and grooming social partners. For each interaction, we also recorded the age category (juvenile or adult), sex (male or female), and kinship (related [relatedness ≥ 0.5] or unrelated) of each interactor to the focal animal, as well as the number of social partners with which each focal animal was observed to interact. Observations were balanced for time of day, with three sessions in the morning and three in the afternoon. (For more information, see the Supplementary Information.)

Cognitive performance

For full accounts of cognitive assessments, please consult Frye, Valure et al. [38] and Frye, Craft et al. [37]. We assessed cognitive function with the Wake Forest Maze Task (WMFT) and Delayed Response Task (DRT) [38]. Maze task performance is thought to reflect components of executive function—e.g., attention, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control [43–45]; the delayed response task assesses working memory [43]. Each assessment was conducted in two phases: (1) a training phase, in which vervets acclimated to and learned the experimental tasks, and (2) a testing phase, in which we assessed each vervet’s performance in the task.

The WFMT consists of 38 mazes of increasing complexity, made using a modified puzzle feeder apparatus (Primate Products). Half of the maze levels are mirror images of the other half to control for directional preferences. For each maze level, subjects were required to navigate a low-quality reward (baby carrot, halved) through the maze to an enlarged opening for retrieval. The vervets were acclimated to the maze task for 30 min/day for 3–5 days, depending on the speed with which they satisfied all pre-testing requirements. Animals were then tested for 30 min/day for 5 days by presentation of the mazes sequentially, from simple to complex [37, 38].

To assess working memory, we employed a modified Wisconsin General Test apparatus, as adapted from prior work with NHPs [43–45]. Hereafter, we refer to this assessment as the Delayed Response Task (DRT). The DRT testing apparatus consisted of three equidistant reward boxes which were separated from the monkey via a raisable, transparent screen. Thus, each box remained in full view of the vervet during the DRT. During DRT trials, the experimenter rewarded a single box, closed the lid, and then waited a pre-determined amount of time. After that time had elapsed, the experimenter raised the transparent screen such that the monkey could select (touch) one of the reward boxes. Vervets were allowed to select a single box during each trial. Trials were scored as “correct” if the monkey selected the baited box and “incorrect” if an un-baited box was selected. During the training phase of the DRT, vervets were required to achieve a criterion of 80% success or better (≤ 6 errors during 30 trials) at a 1-s delay for three consecutive days. Following training, all vervets were then tested at a series of longer delays: 2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 20 s [38]. Increasing delay lengths reflect increasing difficulty in the DRT—i.e., greater demands on working memory. Monkeys that performed better than chance (> 33% accuracy) at the 20-s delay advanced to the 30-s delay. Those that performed better than chance at 30 s advanced to 40 s, and those that performed better than chance at 40 s advanced to the 60-s delay. Thus, a subset of vervets conducted the DRT at 30-, 40-, and 60-s delays. Performance in the DRT was measured as (1) the longest delay achieved in the DRT and the mean accuracy in DRT at the 20-s delay.

Physical performance

We assessed physical performance as usual gait speed and 24-h activity levels. Gait speed was measured in the outdoor pens between March and July 2019 using a well-established protocol [46, 47]. In brief, we measured linear distances between immovable structures (e.g., posts and perches) in each enclosure; these distances averaged 2.26 m (7.41ft). We then used a stopwatch to determine the time required to travel one of these known distances. Measurements were only collected when subjects walked at an unprovoked pace unaffected by interactions with conspecifics. Each subject’s gait speed was calculated as the mean of five separate measurements. We determined levels of activity continuously over 24 h by recording movement via accelerometry (ActiGraph GT3X Triaxial Activity Monitor and ACTILIFE Desktop Software, Pensacola, FL) [48, 49]. Briefly, accelerometers were inserted into nylon mesh protective jackets (Lomir Biomedical Inc.), which the animals wore for three consecutive days. During jacketing procedures, the monkeys were sedated with ketamine hydrochloride (10–15 mg/kg) and outfitted with the jacket along with heart rate telemetry probes and transmitters. Following a 24-h recovery period, accelerometry data were collected for 24 h, after which equipment was removed under light ketamine sedation (5–10 mg/kg). Activity data were processed and analyzed as three-dimensional vector magnitude counts per minute (e.g., Bergqvist-Norén et al. 2020 [50]).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were completed using R version 4.1.3 (R Core Team 2022). Bivariate analyses of social, cognitive, and physical factors with age were implemented with generalized linear mixed models using the “lmer” function in package lmerTest [51] as modified from lme4 [52]. Age was included as a fixed effect predictor, and social group was included as a random intercept. For any variable in which social group explained little variation and prevented model convergence, we re-ran the analysis as a linear model using the “lm” function. For variables with Gaussian residual distributions, we used the “lmer” or “lm” function. For count-based outcome variables (e.g., number of social partners), we used the “glmer” or “glm” function with Poisson distributions. The alpha level was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

To perform mediation analyses, we followed the statistical approach outlined by VanderWeele [53] to assess whether physical and/or cognitive performance mediated the relationships between age and social behavior. Normal gait speed (cm/s) and 24-h activity levels were used as the mediating variables for physical performance (Fig. 1). We used the total number of levels completed in the WFMT, the longest delay achieved in the DRT, and the mean accuracy in DRT at the 20-s delay as the mediating variables for cognitive performances (Fig. 1). We investigated the following dependent variables: (1) the total time spent alone, (2) the total time spent in affiliative behaviors, (3) the total time spent in grooming interactions (both receiving and giving), and (4) the total time grooming conspecifics. We did not adjust analyses for multiple testing as the main objective of this portion of the study was to generate hypotheses concerning the mechanistic underpinnings of physical and/or cognitive effects on social behavior in aging vervet monkeys.

Each mediation analysis consisted of three steps. We first determined whether there were significant bivariate relationships between the predictor variable (age) and each measure of social behavior. If we detected a significant bivariate relationship, we then specified two statistical models: (a) the mediator model for the conditional distribution of the mediators (i.e., metrics of physical and cognitive performance) given the treatment (age) and (b) the outcome model for the conditional distribution of the outcome variable (social behavior) given the predictor (age) and mediator (physical and cognitive performance). Third, we ran the mediation analysis using the mediate function in R [54]. See Supplementary Information for the model equations. We report two decompositions of the total effect: the natural indirect effect and natural direct effect. The natural direct effect is the effect of the predictor on the outcome, accounting for the mediator. The natural indirect effect—a.k.a. causal mediation effect—represents the effect of the predictor on the outcome that is transmitted through the mediator.

Results

Age effects on cognitive performance, physical performance, and social behavior

Age significantly predicted cognitive performance, physical performance, and social behavior. Effects of age are summarized in Table 2. Age was negatively associated with all three measures of cognitive performance: the total number of puzzle levels achieved in the WFMT (executive function; β = − 0.603; p = 0.038), the longest delay achieved in the DR task (working memory; β = − 1.037; p = 0.022), and the average accuracy at the 20-s delay of the DR task (working memory; β = − 0.537; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Bivariate relationships between age and metrics of cognitive performance, physical performance, and social behavior. Up arrows (↑) indicate a significant positive relationship; down arrows (↓) indicate a significant negative relationship. A dash (-) indicates no statistically significant relationship. Statistical significance p < 0.05

| Dependent variable | Direction of age effect |

|---|---|

| Cognitive performance | |

| Executive function (WFMT) | ↓ |

| Working memory (DR – longest delay) | ↓ |

| Working memory (DR – accuracy 20 s) | ↓ |

| Social behavior | |

| Time spent alone | ↑ |

| Time in affiliative interactions | ↓ |

| Time grooming (total) | ↓ |

| Time grooming (given) | ↓ |

| Time grooming (received) | - |

| Time in body contact | - |

| Time in close contact | - |

| Physical function | |

| 24-h activity | ↓ |

| Gait speed | ↓ |

Both metrics of physical performance—gait speed (β = − 1.005; p = 0.043) and 24-h activity levels (log transformed: β = − 0.022; p = 0.003)—were negatively associated with age.

Age was positively associated with the time spent alone, such that older animals spent more time socially isolated (β = 0.723; p = 0.009; Fig. 2A). Since time alone is essentially the reciprocal of time spent in affiliation, age was negatively associated with the overall time spent in affiliative interactions (β = − 0.723; p = 0.009; Fig. 2B). Within the umbrella of affiliation, age was unrelated to the amount of time spent in close (β = − 0.245; p = 0.221) or body contact (β = − 0.143; p = 0.181). Age significantly predicted the total amount of time spent in grooming interactions (β = − 0.293; p = 0.008). However, when we examined grooming versus being groomed, we found that age predicted the amount of time focal monkeys spent grooming conspecifics (β = − 0.217; p < 0.001; Fig. 2C), and not the amount (time) being groomed (β = − 0.057; p = 0.333; Fig. 2D). Thus, the decline in affiliation was not because older animals were being ostracized. To further clarify this distinction, we also determined the relationship between age and the number of social partners with which individuals engaged in grooming interactions and found a similar pattern. Age was negatively associated with the number of partners a focal animal groomed (β = − 0.145; p < 0.001), whereas age was unrelated to the number of partners that groomed the focal animal (β = − 0.050; p = 0.153). To minimize the likelihood of Type I error resulting from assessing the effects of age on multiple facets of social behavior, we conducted the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. The correction did not affect the statistical significance of the comparisons. See Supplementary Information for these analyses.

Fig. 2.

Age-related variation in time (minutes) spent A alone, B in affiliative social interactions, C grooming others, and D being groomed. Age is provided in years

Mediation effects: cognitive and physical performance

We tested whether (1) cognitive performance during the WFMT and DR Task or (2) physical performance (gait speed or 24-h activity) significantly mediated the effects of age on several measures of social behavior. See Table 3 for a complete summary of mediation analyses. For each mediation, we report the following measures: the total effect, the natural indirect effect (a.k.a. causal mediation effect), and natural direct effect. The indirect effect shows the effect of the mediator (cognitive performance or activity levels) on the outcome variable (grooming). The direct effect shows the effect of the main predictor (age) on the outcome (social behavior) after accounting for the effect of the mediator. The total effect indicates the effect of age on the outcome without the effect of the mediator. Overall, we found that physical activity did not significantly mediate the effects of age on any measure of social integration (p’s > 0.290), nor did gait speed (p’s > 0.48). Neither metric of working memory significantly mediated any age effects on social behavior (p’s > 0.35). In contrast, executive function significantly mediated the relationship between age and total amount of time in grooming (β = 0.120; p = 0.047). That is, better performance in the WFMT (i.e., higher executive function) ameliorated the negative effects of age on time in grooming interactions (Fig. 3). When time in grooming interactions was divided into grooming and being groomed, better performance in the WFMT (i.e., higher executive function) tended to mediate negative effects of age on time spent grooming, although the effect was not statistically significant (β = 0.050; p = 0.074), whereas time being groomed was not mediated by cognitive function. Performance in the WFMT did not mediate total time spent in affiliation (β = − 0.121; p = 0.280) or alone (β = 0.121; p = 0.290).

Table 3.

Summary of mediation analyses. In the regressions, the main predictor variable was age; the mediator variables included measures of both cognitive and physical performance; and the outcome variables were the time spent alone, time spent in affliative behavior, time involved in grooming interactions, and time spent grooming conspecifics. · p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

| Cognitive performance | Physical performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive function (WFMT) | Working memory (DR accuracy at 20-s delay) | Working memory (DR longest delay) | Gait speed | 24-h activity | |

| β | β | β | β | β | |

| Time alone | |||||

| Natural indirect | − 0.121 | − 0.114 | 0.116 | 0.035 | 0.045 |

| Natural direct | 0.916*** | 0.938** | 0.719* | 0.610* | 1.154** |

| Total effect | 0.795** | 0.825** | 0.835*** | 0.645* | 1.200*** |

| Time affiliative | |||||

| Natural indirect | 0.121 | 0.119 | − 0.115 | − 0.036 | − 0.045 |

| Natural direct | − 0.922** | − 0.939** | − 0.712* | − 0.614* | − 1.136** |

| Total effect | − 0.797** | − 0.821** | − 0.827** | − 0.649* | − 1.184*** |

| Total grooming | |||||

| Natural indirect | 0.120* | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.115 |

| Natural direct | − 0.416*** | − 0.321* | − 0.307* | − 0.354*** | − 0.496** |

| Total effect | − 0.297** | − 0.295* | − 0.294** | − 0.337*** | − 0.381* |

| Grooming given | |||||

| Natural indirect | 0.050 | − 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.049 |

| Natural direct | − 0.270*** | − 0.214** | − 0.232*** | − 0.250*** | − 0.344*** |

| Total effect | − 0.221*** | − 0.219*** | − 0.217*** | − 0.235*** | − 0.294*** |

Fig. 3.

Executive function significantly mediated the effect of age on the total amount of time spent in grooming interactions (β = 0.120; p = 0.047), such that better performance in WFMT of executive function significantly ameliorated the negative effects of age on social integration

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated age-related decreases in social, physical, and cognitive function in vervets ranging from middle age to geriatric. Like humans, older vervets spent more time alone and had fewer social partners than did their younger conspecifics. Furthermore, frequency of social participation was negatively associated with age, as older individuals spent less time in grooming interactions. Detailed analysis showed that this variation was driven by lower amounts of time spent grooming conspecifics, as the duration of grooming individuals received did not vary by age. In addition to these aging-related differences in social engagement, we found evidence that cognitive rather than physical impairments may mediate the relationships between age and social behavior. Taken together, these findings suggest that aging vervets exhibit social patterns that recapitulate human social aging, and that impairment in executive functioning may precipitate reductions in social engagement as individuals age.

Although increasing social isolation—as indicated by lower frequencies of social interactions—was associated with aging, this relationship was not explained by social exclusion. That is, though older vervets spent more time alone and less time in grooming bouts, the frequency with which they were groomed by others did not vary with age. This pattern is largely consistent with other NHP species. For example, in Barbary macaques, females engaged in fewer grooming bouts and became more spatially reclusive with age, despite continual investment in social relationships from other group members [55, 56]. Likewise, in a large sample (N = 910) of female free-ranging rhesus macaques, the amount of grooming given was lower with age, whereas the amount of grooming an individual received was independent of age [57]. Findings in aging stumptail and Japanese macaques also align with these findings: group members did not exclude elder females from social interactions [31]. Rather, older individuals selectively withdrew from social engagements, maintaining a smaller subset of social partners [31]. The fact that the difference was found in grooming others is significant as grooming functions in bonding, conflict resolution, building coalitions, and increasing tolerance [58–60]. Furthermore, touch is also important in human and NHP health, particularly brain function, as it stimulates neuropeptide release and affiliation-related neural networks [61, 62].

Withdrawal from social interactions may indicate increased social selectivity as individuals age. Indeed, vervets narrowed their social networks, as older individuals engaged with fewer social partners than did younger monkeys. Thus, our results are congruent with human data that suggest that humans reduce their social network size in old age [63, 64] and foster existing relationships during this time [65–68]. In some cases, social withdrawal may reflect underlying pathologic processes that restrict older adults’ abilities and/or comfort with social situations. In humans, declines in social and cognitive function are associated; however, whether these variables are causally related is unclear [7–14]. The data presented here support the hypothesis that associations between age and social participation are mediated by cognitive performance. In particular, executive function (but not working memory) mediated the negative association between age and total time grooming with conspecifics.

In contrast, although both 24-h activity levels and gait speeds decreased with age, neither variable mediated associations between age and social behavior. This is not to suggest that physical performance is unrelated to social aging, as we observe age-related variation in physical performance, and that physical performance predicted cognitive performance a year later [38]. Taken together, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that physical decline precipitates cognitive decline [69], which in turn precipitates social aging. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that interventions to increase or maintain physical function may delay cognitive impairment in humans [70, 71]. However, relationships between physical, cognitive, and social aging are likely multidirectional—i.e., social aging may, in turn, influence physical and cognitive decline. As previously indicated, recent data from humans indicates that reductions in social participation precede cognitive deficits [14, 15]. Thus, just as cognitive decline can contribute to declining physical function [72], decreased social interaction may precipitate physical decrements [19].

An important limitation of our study is that we were only had a relatively short period of time (60 min) to assess each individual’s social behavior. Thus, we may have missed rare behaviors, such as aggression. However, time spent in affiliative behaviors such as grooming and sitting in body contact, and time spent alone have been shown to account for a large percentage of the time budget of NHPs in captive stable long-term social groups [73]; thus, the current observations likely accurately affect these behaviors. Furthermore, the results reported her are congruent with those reported in other nonhuman primate species as discussed above. We also determined that behavior recorded in 40 min of observation was highly correlated with the behavior reported here from 60 min of observation (see Supplementary Information). Nonetheless, additional observation might provide a more nuanced accounting of each vervet’s behavioral profile. Future studies also will benefit from long-term, repeated sampling of social, cognitive, and physical data with which to test age-related temporal relationships between these variables. Understanding the temporal emergence of declines in these three domains will promote the development of appropriate interventions at critical time points in aging.

Conclusions

The results presented here suggest that cognitive deficits, rather than physical deficits, contribute to decreased social engagement in a NHP model, which may indicate a shared biological mechanism precipitating social aging. Future work is needed to better understand the factors underlying social selectivity. Such work may provide insights into the potential benefits and detriments of pruning social networks over the life course.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank David Bissinger, Carson Copeland, Christie Scott, Shanna Wise-Walden, Hannah Register, and Payton Valure for assistance with data collection. We also thank Dr. Haying Chen for her advice on statistical approaches.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health RF1AG058829 (CAS), P30 AG072947, T32AG033534, and R24AG073199, Intramural Grant from the Department of Pathology, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Wake Forest Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center grant P30 AG21332, Vervet Research Colony (P40-OD010965), and the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NCATS UL1TR001420).

Data availability

Data used in this study can be requested at www.Wakeshare.org.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jacob D. Negrey and Brett M. Frye contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Naito R, Leong DP, Bangdiwala SI, McKee M, Subramanian SV, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Avezum A, Yeates KE, Lear SA, Gupta R, Yusufali A, Dans AL, Szuba A, Alhabib KF, Kaur M, Rahman O, Seron P, Diaz R, Puoane T, Liu W, Zhu Y, Sheng Y, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Chifamba J, Rosnah I, Karsidag K, Kelishadi R, Rosengren A, Khatib R, Leela Itty Amma KR, Azam SI, Teo K, Yusuf S. Impact of social isolation on mortality and morbidity in 20 high-income, middle-income and low-income countries in five continents. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e004124. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desrosiers J, Robichaud L, Demers L, Gélinas I, Noreau L, Durand D. Comparison and correlates of participation in older adults without disabilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Strough J. Age differences in reported social networks and well-being. Psychol Aging. 2020;35:159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Waking hours spent alone or with others, by selected characteristics, averages for May to December, 2019 and 2020, American Time Use Survey. 2021.

- 5.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:98–105. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith KJ, Victor C. Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing Soc. 2019;39:1709–1730. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X18000132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nie Y, Richards M, Kubinova R, Titarenko A, Malyutina S, Kozela M, Pajak A, Bobak M, Ruiz M. Social networks and cognitive function in older adults: findings from the HAPIEE study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:570. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James BD, Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Late-life social activity and cognitive decline in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:998–1005. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Béland F, Zunzunegui M-V, Alvarado B, Otero A, del Ser T. Trajectories of cognitive decline and social relations. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2005;60:P320–P330. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Read S, Comas-Herrera A, Grundy E. Social isolation and memory decline in later-life. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2020;75:367–376. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zahodne LB, Ajrouch KJ, Sharifian N, Antonucci TC. Social relations and age-related change in memory. Psychol Aging. 2019;34:751–765. doi: 10.1037/pag0000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Social participation and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults: a community-based longitudinal study. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2016;73:799–806. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara E, Caballero FF, Rico-Uribe LA, Olaya B, Haro JM, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Miret M. Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1613–1622. doi: 10.1002/gps.5174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Lummel RC, Walgaard S, Pijnappels M, Elders PJM, Garcia-Aymerich J, Van Dieën JH, Beek PJ. Physical performance and physical activity in older adults: associated but separate domains of physical function in old age. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, Degens H. Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology. 2016;17:567–580. doi: 10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrempft S, Jackowska M, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:74. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6424-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philip KEJ, Polkey MI, Hopkinson NS, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Social isolation, loneliness and physical performance in older-adults: fixed effects analyses of a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:13908. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70483-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delerue Matos A, Barbosa F, Cunha C, Voss G, Correia F. Social isolation, physical inactivity and inadequate diet among European middle-aged and older adults. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:924. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10956-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosso AL, Taylor JA, Tabb LP, Michael YL. Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. J Aging Health. 2013;25:617–637. doi: 10.1177/0898264313482489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Risbridger S, Walker R, Gray WK, Kamaruzzaman SB, Ai-Vyrn C, Hairi NN, Khoo PL, Pin TM. Social participation’s association with falls and frailty in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. J Frailty Aging. 2022;11:199–205. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2021.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren M, Ganley KJ, Pohl PS. The association between social participation and lower extremity muscle strength, balance, and gait speed in US adults. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benka J, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Macejova Z, Lazurova I, van der Klink JLL, Groothoff JW, van Dijk JP. Social participation in early and established rheumatoid arthritis patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1172–1179. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin S, Trope GE, Buys YM, Badley EM, Thavorn K, Yan P, Nithianandan H, Jin Y-P. Reduced social participation among seniors with self-reported visual impairment and glaucoma. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0218540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Marco A, Cozzolino R, Thierry B. Coping with mortality: responses of monkeys and great apes to collapsed, inanimate and dead conspecifics. Ethol Ecol Evol. 2022;34:1–50. doi: 10.1080/03949370.2021.1893826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veenema HC, Spruijt BM, Gispen WH, van Hooff JARAM. Aging, dominance history, and social behavior in Java-monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:509–515. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(97)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rathke E-M, Fischer J. Social aging in male and female Barbary macaques. Am J Primatol. 2021;83:e23272. doi: 10.1002/ajp.23272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosati AG, Hagberg L, Enigk DK, Otali E, Emery Thompson M, Muller MN, Wrangham RW, Machanda ZP. Social selectivity in aging wild chimpanzees. Science. 2020;370:473–476. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schino G, Pinzaglia M. Age-related changes in the social behavior of tufted capuchin monkeys. Am J Primatol. 2018;80:e22746. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser MD, Tyrrell G. Old age and its behavioral manifestations: a study on two species of macaque. Folia Primatol. 1984;43:24–35. doi: 10.1159/000156168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appt SE, Ethun KF. Reproductive aging and risk for chronic disease: insights from studies of nonhuman primates. Maturitas. 2010;67:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkins HM, Willson CJ, Silverstein M, Jorgensen M, Floyd E, Kaplan JR, Appt SE. Characterization of ovarian aging and reproductive senescence in vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) Comp Med. 2014;64:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox LA, Olivier M, Spradling-Reeves K, Karere GM, Comuzzie AG, VandeBerg JL. Nonhuman primates and translational research-cardiovascular disease. ILAR J. 2017;58:235–250. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilx025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kavanagh K, Day SM, Pait MC, Mortiz WR, Newgard CB, Ilkayeva O, McClain DA, Macauley SL. Type-2-diabetes alters CSF but not plasma metabolomic and AD risk profiles in vervet monkeys. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:843. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson QN, Wells M, Davis AT, Sherrill C, Tsilimigras MCB, Jones RB, Fodor AA, Kavanagh K. Greater microbial translocation and vulnerability to metabolic disease in healthy aged female monkeys. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11373. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frye BM, Craft S, Latimer CS, Keene CD, Montine TJ, Register TC, Orr ME, Kavanagh K, Macauley SL, Shively CA. Aging-related Alzheimer’s disease-like neuropathology and functional decline in captive vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) Am J Primatol. 2021;83:e23260. doi: 10.1002/ajp.23260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frye BM, Valure PM, Craft S, Baxter MG, Scott C, Wise-Walden S, Bissinger DW, Register HM, Copeland C, Jorgensen MJ, Justice JN, Kritchevsky SB, Register TC, Shively CA. Temporal emergence of age-associated changes in cognitive and physical function in vervets (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) GeroScience. 2021;43:1303–1315. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00338-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen JA, Fears SC, Jasinska AJ, Huang A, Al-Sharif NB, Scheibel KE, Dyer TD, Fagan AM, Blangero J, Woods R, Jorgensen MJ, Kaplan JR, Freimer NB, Coppola G. Neurodegenerative disease biomarkers Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, tau, and p-tau181 in the vervet monkey cerebrospinal fluid: relation to normal aging, genetic influences, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00903. doi: 10.1002/brb3.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jasinska AJ, Haghani A, Zoller JA, Li CZ, Arneson A, Ernst J, Kavanagh K, Jorgensen MJ, Mattison JA, Wojta K, Choi O-W, DeYoung J, Li X, Rao AW, Coppola G, Freimer NB, Woods RP, Horvath S. Epigenetic clock and methylation studies in vervet monkeys. Geroscience. 2022;44:699–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Altmann J. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour. 1974;49:227–266. doi: 10.1163/156853974X00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.James AS, Groman SM, Seu E, Jorgensen M, Fairbanks LA, Jentsch JD. Dimensions of impulsivity are associated with poor spatial working memory performance in monkeys. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci. 2007;27:14358–14364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4508-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobsen CF. Functions of frontal association area in primates. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1935;33:558–569. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1935.02250150108009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldman PS, Rosvold HE, Vest B, Galkin TW. Analysis of the delayed-alternation deficit produced by dorsolateral prefrontal lesions in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1971;77:212–220. doi: 10.1037/h0031649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shively CA, Willard SL, Register TC, Bennett AJ, Pierre PJ, Laudenslager ML, Kitzman DW, Childers MK, Grange RW, Kritchevsky SB. Aging and physical mobility in group-housed Old World monkeys. Age. 2012;34:1123–1131. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9350-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Justice JN, Silverstein-Metzler MG, Uberseder B, Appt SE, Clarkson TB, Register TC, Kritchevsky SB, Shively CA. Relationships of depressive behavior and sertraline treatment with walking speed and activity in older female nonhuman primates. Geroscience. 2017;39:585–600. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shively CA. Social subordination stress, behavior, and central monoaminergic function in female cynomolgus monkeys. Biol Psychiat. 1998;44:882–891. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00437-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverstein-Metzler MG, Shively CA, Clarkson TB, Appt SE, Carr JJ, Kritchevsky SB, Jones SR, Register TC. Sertraline inhibits increases in body fat and carbohydrate dysregulation in adult female cynomolgus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;68:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergqvist-Norén L, Johansson E, Xiu L, Hagman E, Marcus C, Hagströmer M. Patterns and correlates of objectively measured physical activity in 3-year-old children. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:209. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02100-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw. 2017;82:1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.VanderWeele TJ. A three-way decomposition of a total effect into direct, indirect, and interactive effects. Epidemiology. 2013;24:224–232. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318281a64e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. mediation: R Package for Causal Mediation Analysis. J Stat Softw. 2014;59:1–38. doi: 10.18637/jss.v059.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Almeling L, Sennhenn-Reulen H, Hammerschmidt K, Freund AM, Fischer J. Social interactions and activity patterns of old Barbary macaques: further insights into the foundations of social selectivity. Am J Primatol. 2017;79:e22711. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Almeling L, Hammerschmidt K, Sennhenn-Reulen H, Freund AM, Fischer J. Motivational shifts in aging monkeys and the origins of social selectivity. Curr Biol. 2016;26:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brent LJN, Ruiz-Lambides A, Platt ML. Family network size and survival across the lifespan of female macaques. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284:20170515. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manson JH, Navarrete CD, Silk JB, Susan P. Time-matched grooming in female primates? New analyses from two species. Anim Behav. 2004;67:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borgeaud C, Schnider A, Krützen M, Bshary R. Female vervet monkeys fine-tune decisions on tolerance versus conflict in a communication network. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284:20171922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Surbeck M, Boesch C, Girard-Buttoz C, Crockford C, Hohmann G, Wittig RM. Comparison of male conflict behavior in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan paniscus), with specific regard to coalition and post-conflict behavior. Am J Primatol. 2017;79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Dunbar RI. The social role of touch in humans and primates: behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bora E, Yucel M, Allen NB. Neurobiology of human affiliative behaviour: implications for psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:320–325. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328329e970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weijs-Perrée M, van den Berg P, Arentze T, Kemperman A. Factors influencing social satisfaction and loneliness: a path analysis. J Transp Geogr. 2015;45:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang F, Lee Y. Social support networks and expectations for aging in place and moving. Res Aging. 2011;33:444–464. doi: 10.1177/0164027511400631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lansford JE, Sherman AM, Antonucci TC. Satisfaction with social networks: an examination of socioemotional selectivity theory across cohorts. Psychol Aging. 1998;13:544–552. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:331–338. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wrzus C, Hänel M, Wagner J, Neyer FJ. Social network changes and life events across the life span: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:53–80. doi: 10.1037/a0028601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.English T, Carstensen LL. Selective narrowing of social networks across adulthood is associated with improved emotional experience in daily life. Int J Behav Dev. 2014;38:195–202. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skillbäck T, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Skoog J, Rydén L, Wetterberg H, Guo X, Sacuiu S, Mielke MM, Zettergren A, Skoog I, Kern S. Slowing gait speed precedes cognitive decline by several years. Alzheimer's Dement: J Alzheimer's Assoc. 2022;18:1667–1676. doi: 10.1002/alz.12537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng S-T, Chow PK, Song Y-Q, Yu ECS, Chan ACM, Lee TMC, Lam JHM. Mental and physical activities delay cognitive decline in older persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laurin D, Verreault R, Lindsay J, MacPherson K, Rockwood K. Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:498–504. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gray M, Gills JL, Glenn JM, Vincenzo JL, Walter CS, Madero EN, Hall A, Fuseya N, Bott NT. Cognitive decline negatively impacts physical function. Exp Gerontol. 2021;143:111164. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.111164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson CSC, Frye BM, Register TC, Snyder-Mackler N, Shively CA. Mediterranean diet reduces social isolation and anxiety in adult female nonhuman primates. Nutrients. 2022;14:2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study can be requested at www.Wakeshare.org.