Abstract

Background

Globally, one of the measures of high performing healthcare facilities is the compliance of patient safety culture, which encompasses the ability of health institutions to avoid or drastically reduce patient harm or risks. These risks or harm is linked with numerous adverse patient outcomes such as medication error, infections, unsafe surgery and diagnosis error.

Objectives

The general objective of this study was to investigate into the impact of patient safety culture practices experienced on patient satisfaction among patients who attend the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital in the Takoradi municipality.

Methods

This study was a descriptive cross-sectional study and a consecutive sampling technique was used to select 336 respondents for the study. Data was collected using a structured questionnaire and processed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences, V.21. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were carried out and result were presented using figures and tables.

Results

The study found that the overall patient safety compliance level observed by the respondents was poor (29.2%). The prevalence of adverse events experienced among the respondents was high (58%). The leading adverse events mentioned were medication errors, followed by wrong prescriptions and infections. The consequences of these adverse events encountered by the respondents were mentioned as increased healthcare costs (52%), followed by hospitalisation (43%), worsening of health conditions (41%) and contraction of chronic health conditions (22%). Patient safety cultural practices such as teamwork (β=0.17, p=0.03), response to error (β=0.16, p=0.005), communication openness (β=0.17, p=0.003) and handoffs and information exchange (β=0.17, p=0.002) were found to positively influence patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

The poor general compliance of the patient safety culture in the facility is unfortunate, and this can affect healthcare outcomes significantly. The study therefore entreats facility managers and various stakeholders to see patient safety care as an imperative approach to delivering quality essential healthcare and to act accordingly to create an environment that supports it.

Keywords: Health policy, Decision Making, Health Equity, Clinical governance

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The cross-sectional study helped to describe the characteristics of the population under investigation.

Parametric assumptions were met to ensure reliable results.

A representative sample size was used.

The effect due to time was not captured due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design.

The consecutive sampling technique could introduce biases in sampling.

Background of the study

Patient safety culture is an essential factor in determining the ability of hospitals to treat and reduce patient risks.1 Patient safety is regarded as an international health concern affecting patients in various healthcare settings globally. This is due to the complexity of healthcare systems and the increase in unsafe care delivered to patients in various health institutions.2 3 The global healthcare landscape is said to be undergoing a transformative shift as health systems continue to operate within increasingly complex environments4 driven by technology. Though fresh actions, emerging technologies and care models can have healing prospect, they can also trigger different dangers to safe care. Patient safety is a vital standard of healthcare and is now being acknowledged as a huge and rising global public health encounter. Worldwide determinations to decrease the affliction of patient harm have not accomplished considerable transformation over the previous one and half decades. As also highlighted by the WHO, unsafe care leading to adverse events is said to have the potential to be counted among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide5 with associated annual cost amounting to trillions.6 It, thus, indicate that patient safety during care is crucial in improving health in a long term.

Patient safety culture is an integrated pattern of individual and organisational behaviour. This is based on shared beliefs and values that continuously seek to minimise the patient harm, which may result from the process of care delivery.3 It is also referred to as the outcome of individual and organisation’s values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and patterns of behaviour that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organisation’s health and safety management.7 Patient safety and related practices or activities include but not limited to patient and family engagement and communication; management support; response to error; adherence to ethical practices such as respect, privacy and confidentiality; adherence to clinical protocols in the delivery of care such as proper hand washing practices; personnel training on quality improvement and relations; and use of standard and certified medical devices, among others in healthcare organisations.1 8–10

All these could be achieved through setting up clear policies, having skilled healthcare professionals, all-level leadership, up-to-date data and patient-centred care in order to maintain healthcare safety sustainability.3 Several studies stress the importance of patient safety culture for patient safety processes and outcomes.11 More specifically, research has shown that a sound patient safety culture is associated with fewer adverse events12 and more positive patient experiences.13

A systematic review11 found that a positive workplace culture was related to several desirable patient outcomes, such as fewer infections, reduced rates of mortalities and increased patient satisfaction. Studies have also shown that promoting patient safety culture among healthcare providers is a key to reducing adverse events and maintaining quality of care.14

Adverse events also known as medical errors are one of the numerous factors that affect patient safety within health facilities. Adverse events are unintended injuries or complications that are caused by healthcare management rather than by the patient’s underlying disease. These can lead to death, disability at the time of discharge and prolonged hospital stay.15 Adverse events or medical errors that significantly contribute to unsafe care and harm to patients which subsequently affect patient safety are medication errors, nosocomial infections, unsafe surgeries, wrong injections, procedures and diagnostic errors.16 The prevalence of adverse events by medical professionals has been alarming.

In Iran, a review study revealed that the prevalence of adverse events exists between 10% and 80%.17 Another study conducted on the prevalence of adverse events revealed that about 7 out of 10 selected professional nurses declared engaging in adverse events resulting in harm to patients.18

Measures taken to improve on patient safety have demonstrated different levels of effectiveness.19 Moreover, several prior studies conducted among medical staff have shown that higher levels of awareness of patient safety culture are associated with higher patient overall satisfaction and lower occurrence of adverse events.20 21 In Ghana, the vital points acknowledged in the patient safety situational exploration were knowledge and learning in patient safety while, patient safety surveillance was the frailest act identified. There were also flaws in areas such as national patient policy, healthcare-related infections, surgical safety, patient safety partnerships and patient safety funding, respectively.22 It is against this background that the researchers seek to investigate into patient safety culture among patients and its impact on their overall satisfaction of care received at the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital in the Takoradi municipality of Ghana.

Objectives

The general objective of this study is to investigate the impact of patient safety culture experienced on patient satisfaction among patients who attend the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital Takoradi. Specifically, this study sought to: (1) assess patient safety culture protocol compliance at Kwesimintsim Government Hospital, Takoradi municipality, (2) measure the prevalence of adverse events of patient safety culture protocols compliance and their effects on patients safety among patients who attend Kwesimintsim Government Hospital, Takoradi, and (3) determine the impact of patient safety culture practises on patient satisfaction among patients who attend the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital, Takoradi.

Methods

This study deployed a facility-based cross-sectional study design using a quantitative approach to obtain the necessary data required for the accomplishment of the study. This design and approach to research focuses on carefully measuring a set of variables to answer theory-guided research questions or hypotheses.23 The study was conducted at Kwesimintsim Government Hospital because of its strategic location and the numerous communities it serves. The Kwesimintsim Government Hospital was selected due to its size, as well as the number of communities it serves.

The Kwesimintsim Government Hospital is the district hospital for the Effia-Kwesimintsim Municipal Assembly in Ghana. It is the referral point for an estimated population of 89 342 and the second major referral health facility in Takoradi. The hospital was established in 1977 and was expected to cater for the healthcare needs of the communities in and around the Kwesimintsim municipality but the facility is now serving the communities beyond its catchment area including Ahanta West, Mpohor, Wassa East and the Tarkwa Nsuaem districts. The hospital supervises other health institutions (both private and public) within the Kwesimintsim submetro. The subdistricts are West Tanokrom, Lagos town, Sawmill, Kwesimintsim town, Kwesimintsim Zongo, Anaji and Apramdo.

A five-member management team made up of the medical superintendent, health service administrator, the head of nursing, the head of pharmacy and the head of finance guides the operations of the hospital. There are also a number of operational committees, which help in the management of the hospital. They include the disciplinary committee, the audit committee, the welfare committee, the entity tender committee and data validation committee, among others.24

The target population for this study encompassed all individuals seeking healthcare services at the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital in Ghana. Therefore, the estimated number of 89 342 patients served by the facility was considered as the size of the target population. The assumptions of using Yamanae’s25 sampling formula to compute the sampling size was based on a 95% CI and 5% margin of error. To achieve a statistical power of 0.9 and at an alpha level of 0.05, the study computed the sampling size as follows: ,

where n is the sample size, N is the study population size for the proposed period of data collection and e is the level of precision. The study population (N) for this study is presumed to be 89 342. The level of precision (e) is 0.05 (95% CI).

n=398.23.

Therefore, 398 was the estimated sample size for the study.

Consecutive sampling method, whereby every eligible and available participant, was recruited until the desired sample size was reached based on the inclusion criteria applied in this study. This method was appropriate for the study because of the ill-health conditions of patients, which often made some of them not fit or ready for data collection. The study recruited patients who visited the hospital during the data collection period. To ensure ethical compliance, prior to their participation, all patients involved in the study provided informed consent by signing the consent form. Additionally, the hospital granted its approval for the study. The study excluded inpatients admitted to the hospital due to their perceived inability due to ill-health (ie, inability to perhaps not provide accurate responses).

A structured (closed and open-ended) questionnaire was used to collect data from the sampled respondents. The questionnaire was self-administered and a high level of discretion was kept to protect the identities and views of the respondents. The questionnaire was made up of four parts. The first part interrogated the respondents on their demographic data. The second part interrogated the respondents on the compliance of patient safety culture protocols witnessed in the facility. The third part interrogated the respondents on adverse events they have experienced in the health facility and their consequences on them. The final part of the questionnaire interrogated the respondents on their satisfaction regarding patient safety culture practices witnessed and care received at the health facility. Patient satisfaction and safety cultural practices were the main dependent and independent variables of the study, respectively. The study considered seven independent safety culture and related practices and these include: frequency of event reported, teamwork, response to error, communication openness, management support, handoffs, information exchange and staffing.

In order to ensure the validity of the content of the questionnaires, they were given to two experts who understood the topic under investigation to comment and add their input. The patient safety practices were adapted from Arabloo et al.26 The study used single-item measures for the variables used in the inferential statistics because of brevity and the need to assess several constructs27; hence, there was no need to carry out construct validity analyses such as confirmatory factor analysis and others. Nevertheless, various tests needed to confirm parametric assumptions such as normality, homogeneity of variance and multicollinearity, among others, to ensure reliable estimation were carried out and met before the main inferential analysis of interest was carried out.

Data obtained from the study were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and imported into SPSS computational tool (V.22) to generate the study findings. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were carried out and result visualised using tables and figures. The study was conducted between 2 September 2022 and 30 June 2023 and achieved a response rate of 84%.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public’s involvement was encountered during the gap identification stage, the questionnaire design stage and the data collection stage. The areas to be explored and wording of items were discussed with randomly selected patients prior to the data collection, and their output was considered during the final design of the questionnaire. The facility engagement resulted in the approval of the study and the nomination of staff to assist in the data collection process. The authors also intend to disseminate the published results of the study to the public through a seminar at the hospital and various community communication channels.

Data sharing statement

The data for this study would be made available on a written request.

Presentation of results

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

In all, 336 respondents responded to the study. More than half of the respondents (n=212, 63%) were females and males constituted 37% of the respondents (n=124). More than half of the respondents were aged 31–40 years (n=181, 54%), followed by respondents aged 21–30 years (n=121, 36%), respondents aged 41 years and above (n=24, 7%) and less than a quarter (n=10, 3%) were aged 16–20 years. An overwhelming majority of the respondents were Christians (n=319, 95%) and the remaining few were Muslims (n=17, 5%). Majority of the respondents were single in terms of marital status (n=212) denoting 63% of the respondents, a little over one-fourth were married (n=94, 28%) and almost 1 out of every 10 respondents was a divorcee (n=30, 9%). With respect to the educational qualification of the 336 respondents, almost half of them were basic school and senior high school graduates (n=155, 46%), followed by respondents with no formal education (n=19, 6%) and very minute portion of the respondents (n=7, 2%) were University graduates. With regard to the employment category of the respondents, almost half of them were self-employed (n=165, 49%), followed by more than one-third who were unemployed (n=128, 38%), followed by students who were 27 in number (8%), followed by respondents who were private sector employees (n=13, 4%) and only 1 of the respondents (1%) was a government employee. Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Females | 124 | 36.90 |

| Males | 212 | 63.10 |

| Age | ||

| 16–20 | 10 | 2.98 |

| 21–30 | 121 | 36.01 |

| 31–40 | 181 | 53.87 |

| 41 and above | 24 | 7.14 |

| Marital | ||

| Single | 212 | 63.10 |

| Married | 94 | 27.98 |

| Divorced | 30 | 8.93 |

| Religion | ||

| Christians | 319 | 94.94 |

| Muslims | 17 | 5.06 |

| Employment category | ||

| Unemployed | 128 | 38.10 |

| Government employee | 3 | 0.89 |

| Private sector employee | 13 | 3.87 |

| Self-employed | 165 | 49.11 |

| Student | 27 | 8.04 |

| Educational qualification | ||

| No formal education | 19 | 5.65 |

| Basic education | 155 | 46.13 |

| Secondary education | 155 | 46.13 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 | 2.08 |

Patient safety culture protocols compliance

The first objective of the study was to assess patient safety culture protocols compliance by health workers and management of the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital in the Takoradi municipality from the perspectives of patients. The study presented 13 patient safety protocol statements for which the respondents (patients) were asked to state if each of the protocols were observed by staff and qmanagement of the health facility. The overall score for compliance was computed through evaluating the mean score of the protocols investigated. The overall safety protocol compliance level was found to be very abysmal (29.2%) in this study. Table 2 presents these findings.

Table 2.

Patient safety culture protocols compliance

| Safety protocols | Frequency of yes responses (n=336) | Percentage (%) |

| When one unit gets busy, other health workers help. | 306 | 91.1 |

| Staff actively do things to improve patient safety. | 115 | 34.2 |

| Hospital units work well together to provide the best care for patients. | 245 | 72.9 |

| Hospital management provides a work climate that promotes patient safety. | 175 | 52.1 |

| The actions of hospital management show that patient safety is a top priority. | 160 | 47.6 |

| Important patient care information is often not lost among staff. | 199 | 59.2 |

| Problems do not often occur in the exchange of information across the units. | 44 | 13.1 |

| Patient safety is never sacrificed to get work done. | 30 | 8.9 |

| The procedures and systems at the facility are good at preventing errors. | 0 | 0 |

| Staff freely speak up if they see something that may negatively affect patient care. | 0 | 0 |

| Staff feel free to question the decisions of those with more authority. | 0 | 0 |

| Staff are not afraid to ask questions when something does not seem right. | 0 | 0 |

| Staff report any error they make to promote patient safety. | 3 | 0.9 |

| Overall average compliance rate (%). | 29.2 |

n, total number of respondents.

Prevalence of adverse events of patient safety culture protocols compliance and their effects on patient’s safety

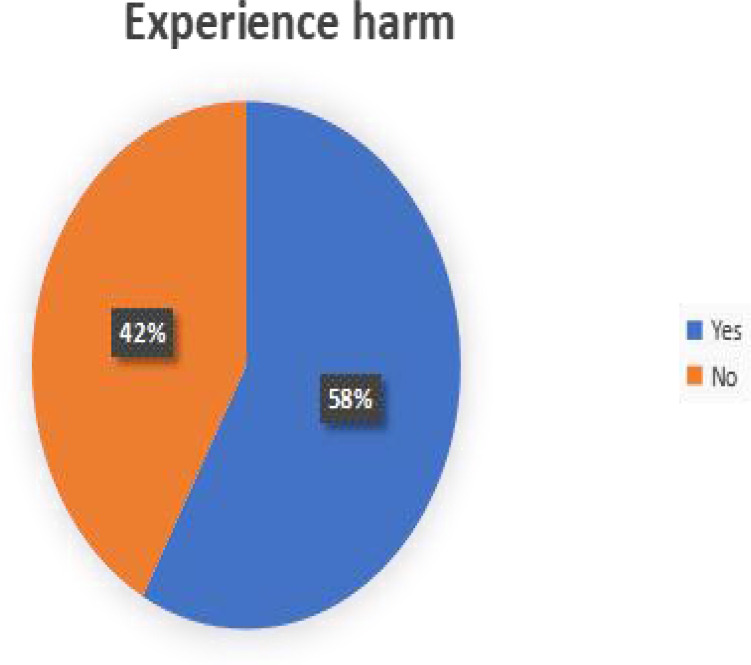

To assess the adverse events of patient safety culture protocols compliance, respondent were asked to indicate whether they have encountered harm or problem as a result of care received at the facility for the past 3 years. As in figure 1, 195 representing 58% of the respondents indicated that they have incurred harm before as a result of care received at the facility for the past 3 years. See online supplemental figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of adverse events of patient safety culture protocols compliance. Source: authors’ construct, 2022.

bmjopen-2023-073190supp001.pdf (362.1KB, pdf)

The study further asked those who indicated that they have experience harm before as a result of care received to identify or associate the possible harm received or problem encountered across a list of problems or harm. Medical error followed by wrong prescription and infections were found to be the most problems or harm encountered as a result of none adherence to patient safety culture protocol compliance as detailed in table 3.

Table 3.

Harms or problems encountered as a result of none adherence to patient safety culture protocol compliance

| Problems/harms encountered | Frequency (n=195) | Percentage (%) |

| Medication error | 105 | 53.8 |

| Infections | 96 | 49.2 |

| Unsafe surgery | 21 | 10.8 |

| Diagnosis error | 86 | 46.1 |

| Wrong injection | 45 | 23.1 |

| Wrong treatment procedure | 91 | 46.7 |

| Wrong prescription | 101 | 51.8 |

n, number of people who indicated they have experience problem or harm in the cause of receiving care.

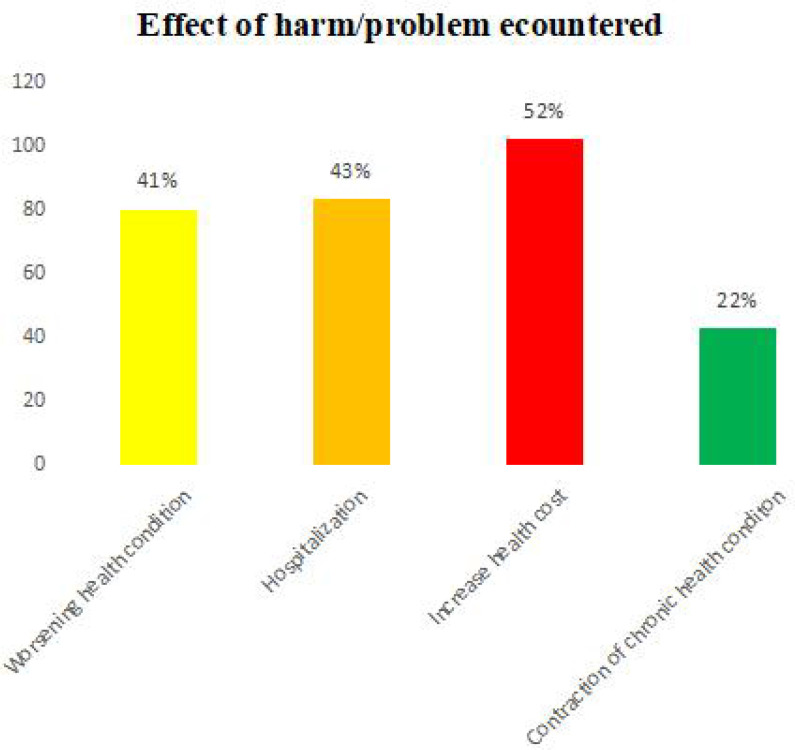

Respondent were again asked to indicate the effect such problems or harm encountered at the facility yields to. Increasing of health expenditure (n=102) followed by hospitalisation (n=83) and worsening of health condition (n=80) were the popular effect mentioned as shown in figure 2. See online supplemental figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effect of harms or problems encountered as a result of none adherence to patient safety culture protocol compliance. Source: authors’ construct, 2022.

Inferential statistics

The final objective of this study was to determine the impact of patient safety culture practices on patient satisfaction. The study established this through regression analysis. Before undertaking such analysis, certain assumptions were very crucial to be met in order to product accurate and robust results. The first assumption to be explored was multicollinearity. Table 4 shows the correlation matrix between the dependent (patient satisfaction) and safety culture practices (ie, variables 2–8), the independent variables. The result of the correlations was examined using the Holm correction to adjust for multiple comparisons based on an alpha value of 0.05. It could be observed that there is no multicollinearity present. This is because there is no correlation between any of the variables exceeding 0.5.

Table 4.

Correlation between the independent and dependent variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Satisfaction | 1 | 0.02 | 0.17* | 0.11 | 0.19* | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.17* |

| Frequency of event reported | 0.02 | 1 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.12 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.23* |

| Teamwork | 0.17* | 0.06 | 1 | 0.19* | 0.17* | −0.16 | −0.09 | 0.11 |

| Response to error | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.19* | 1 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.28* | −0.05 |

| Communication openness | 0.19* | −0.12 | 0.17* | −0.12 | 1 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.24* |

| Management support | 0.03 | 0.1 | −0.16 | −0.12 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.23* | 0 |

| Handoffs and information exchange | 0.13 | 0.1 | −0.09 | −0.28* | −0.03 | 0.23* | 1 | 0.11 |

| Staffing | 0.17* | −0.23* | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.24* | 0 | 0.11 | 1 |

**P value is significant.

The normality assumption was explored with the Q–Q plot, and the result did not deviate much from normality; besides, the sample size was even greater enough to evoke the central limit theorem. Studentised residuals plot for outlier detection was explored and there was no presence of outlier. The assumption of homoscedasticity was tested using the Breusch-Pagan the result turns to be insignificant indicating homoscedasticity. We provided all these assumption analyses in online supplemental appendix. Following the satisfactory fulfilment of these crucial parametric assumptions, we conducted the regression analysis. As indicated in table 5, the regression model exhibited statistical significance, as evidenced by the F-statistic and R2 values (F (7,325)=5.71, p<0.001, R2=0.11).

Table 5.

Model fit measures

| Overall model test | |||||

| R | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | P value |

| 0.331 | 0.11 | 5.71 | 7 | 325 | <0.001 |

From the regression output (see table 6), it is established again that there is no presence of multicollinearity looking at the variance inflation factor across all the independent variable indicating some level of confidence in the regression output. From the regression output, it is observed that teamwork (β=0.17, p=0.03), response to error (β=0.16, p=0.005), communication openness (β=0.17, p=0.003) and Handoffs and information exchange (β=0.17, p=0.002) all significantly predict patient satisfaction. Management support, frequency of event reported and staffing did not, however, significantly predict patient satisfaction at the selected significant level of 0.05.

Table 6.

Results for linear regression with frequency of event reported, teamwork, response to error, communication openness, management support, handoffs and information exchange, and staffing predicting patient satisfaction

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | β | t | P value | VIF |

| (Intercept) | 0.46 | 0.36 | −0.25 to 1.18 | 0 | 1.27 | 0.206 | |

| Frequency of event reported | 0.006 | 0.04 | −0.07 to 0.08 | 0.008 | 0.15 | 0.88 | 1.1 |

| Teamwork | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.004 to 0.07 | 0.12 | 2.16 | 0.031 | 1.13 |

| Response to error | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.18 | 0.16 | 2.85 | 0.005 | 1.15 |

| Communication openness | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.06 to 0.28 | 0.17 | 3 | 0.003 | 1.12 |

| Management support | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.07 to 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.686 | 1.09 |

| Handoffs and information exchange | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.05 to 0.21 | 0.17 | 3.07 | 0.002 | 1.17 |

| Staffing | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.005 to 0.16 | 0.1 | 1.85 | 0.065 | 1.15 |

VIF, variance inflation factor.

Discussion

This study sought to assess patient safety culture compliance, determine the prevalence of adverse events related to patient safety culture protocols and their effects and evaluate the impact of patient safety culture practices on patient satisfaction.

Patient safety culture compliance has become the sine qua non approach to delivering healthcare that does not only minimise medical errors but also captures the responsiveness of a healthcare system entrenched in meeting patient’s frivolous expectations. The WHO recognised patient safety-centred care as the pivotal foundation for delivering quality essential health services.3 It is unfortunate that the study’s findings on safety culture compliance overall estimation was not that appreciable (29.2% adherence rate) and therefore seems to support the existing evidence.5 17 18 On the other hand, it is not surprising to observe this outcome given the study setting. Reports from the media in Ghana have consistently highlighted how patients are taken for granted especially in government healthcare facilities. This ill safety culture compliance could be attributed to several factors. Medical negligence on the part of the healthcare profession as documented in the country,28 poor facility management and supervision,3 infrastructure and technological limitation among others. Infrastructure and appropriate technology to meet the needs of the population who are constantly seeking care is a deficit or limitation for almost every Ghanaian government healthcare facility. Even so, poor management and supervision may be the most plausible factor for the ill patient safety culture compliance among professionals since it is common to observe government institutions, including healthcare facilities, being operational but lacking effective management. Public workers often prioritise their monthly remuneration over the quality and quantity of their output, in contrast to their counterparts in the private sector. Facility managers and leaders could do better in ensuring proper supervision.

The reported ill patient safety culture compliance among professionals in the study collides with the resulting significant number of people (58% of the respondents) who claim to have experienced harm or problems due to receiving care at the facility. This finding outcome was also in consistence with the finding of some existing studies, where the prevalence of adverse events was estimated from 10% to 80%.17 18 Medical errors, wrong prescription, infections and hospitalisation mentioned in the literature as being part of the problem or harm often encountered when receiving care16 is also highlighted in the study. Hygienic practices in most Ghanaian healthcare facilities are not up to standard even at the top resourced tertiary facilities and so the infection rate reported in the study may not be overestimated. With several trained professional teachers in the country (Ghana) who cannot spell basic daily words correctly and write clearly,29 it is not unlikely that their counterpart (trained nurses) who administer medication and in some instances prescribe medications (even though not certified for prescribing drugs) together with trained medical doctors offer or lure patients into getting wrong medications as observed in the study.

Such anomaly (patient harm) in healthcare delivery most often elongate time and resource spent in seeking care, and so increasing of healthcare cost as the leading effect of this anomaly captured by the study was not unexpected. It is estimated that the aggregate costs of patient harm amount to trillions of dollars each year.6 With a significant number of people in Ghana living below the poverty line,30 this could jeopardise people’s willingness to seek appropriate healthcare. Hospitalisation and worsening of healthcare conditions as a result of adverse events in patient safety culture protocols and compliance rates in the study are also concerning. If the attempt to seek healthcare is perceived to be accompanied by a new and deteriorating health condition, then a rational being would desist from making such attempts. The consequent effect may include routine self-medication and a delay in seeking appropriate healthcare services.

The study’s last objective was to evaluate the impact of patient safety culture practices on patient satisfaction in the Ghanaian context, since the two have been found to be associated with each other.11 14 The study found four key patient safety practices that predict patient satisfaction including teamwork, responsiveness to error, communication openness and handoffs and information exchange. If patient sees professional working as a team by supporting each other in addressing their healthcare needs, then they are likely to feel welcome to the facility and appreciate the healthcare professionals’ efforts either than each professional appearing to be working on a function and tossing patients around without effective coordination. Moreover, if professionals are found admitting their limitations as human when they encounter them, a certain level of trust would be built and hence improve patient–professional relationship and the same argument holds for effective exchange of information and openness to communication. All of these would go a long way of reducing adverse events and ensuring some level of quality of care.14 These practices do not require hard or external resources, hence constant training of healthcare professional on these patient safety culture practices with effective management and supervision thereafter could play a major in creating a healthcare atmosphere that thrives on patient safety culture.

The findings of this study identify a possible gap in patient safety care in the Ghanaian public healthcare system and recognise managers and leaders of the various healthcare facilities as catalysts to stimulate an atmosphere that supports patient safety-centred care given the forever anticipated limited available healthcare resources.

Conclusion

One of the hallmarks of modern healthcare institutions is the compliance of patient safety-centred care. This approach to healthcare delivery exposes patients to less risks and harm at the health facilities. The study, however, identified poor patient safety care and associated harms and effect. The study also identified teamwork, effective communication and free exchange of information as having a positive impact on patient satisfaction. The study therefore entreats facility managers and various stakeholders to see patient safety care as an imperative approach to delivering quality essential healthcare services and monitor and implement novel interventions to promote and sustain patient safety protocol compliance in their respective settings.

Study limitations

Just as in any empirical study, this particular inquiry is likewise susceptible to various methodological constraints, although concerted efforts were exerted to mitigate a subset of these limitations. The study used a cross-sectional survey, implying that changes due to time were not captured. The consecutive sampling technique deployed in the study also implies that several benefits of probabilistic sampling may not be attained. Finally, even though the sample size was adequate given the sampling technique and context of the study, including other facilities in the region with a larger sample size would have enriched the findings and allowed for comparative analysis. Given the aforementioned limitations, the study contends that it is pivotal and incumbent to undertake additional research endeavours as a means of procuring an enriched and holistic understanding of patient safety care. This includes the examination of supplementary secondary facilities pertaining to the topic at hand, thereby engendering a more all-encompassing apprehension of the topic’s intricate dynamics nationwide. By encompassing other pertinent facilities within forthcoming investigations, a more expansive purview can be attained, resulting in heightened discernment and profound elucidation regarding patient safety care in Ghana.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to conception of the idea, contributed to analysis, acquisition or interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript and gave approval. Design of study: CO-AB and POAhimah. Date collection: POAhimah. Analysis and or interpretation of data: CO-AB, AAB, POAhimah, FA, POAdoma, EK, DSB, EAB, VK and JBKK. Drafting the manuscript: CO-AB, AAB, POAhimah, FA, POAdoma, EK, DSB, EAB, VK and JBKK: Revising and proofreading of the manuscript: CO-AB, AAB, POAhimah, FA, POAdoma, EK, DSB, EAB, VK and JBKK. All authors read and approved that this manuscript be submitted to BMJ OPEN for publication. CO-AB is the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Ethics Approval Statement: The approval was obtained from the Kwesimintsim Government Hospital before data collection commenced. The study sought ethical approval from its study sitting and its reference number is: GHS/WR/EKMA/KH/ATT/2022.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Kakemam E, Albelbeisi AH, Davoodabadi S, et al. Patient safety culture in Iranian teaching hospitals: baseline assessment, opportunities for improvement and benchmarking. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:403. 10.1186/s12913-022-07774-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamdan M, Saleem AA. Changes in patient safety culture in Palestinian public hospitals: impact of quality and patient safety initiatives and programs. J Patient Saf 2018;14:e67–73. 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Organisation . Patient Safety, Key facts. 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatzi AV, Malliarou M. The need for a nursing specific patient safety definition, a viewpoint paper. IJHG 2023;28:108–16. 10.1108/IJHG-12-2022-0110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha A. Patient safety–a grand challenge for Healthcare professionals and policymakers alike. In: Roundtable at the Grand Challenges Meeting of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slawomirski L, Auraaen A, Klazinga NS. The economics of patient safety: strengthening a value-based approach to reducing patient harm at national level.2017 Mar. Available: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/The-economics-of-patient-safety-March-2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Sherbiny NA, Ibrahim EH, Abdel-Wahed WY. Assessment of patient safety culture among Paramedical personnel at general and District hospitals, Fayoum Governorate. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 2020;95:4. 10.1186/s42506-019-0031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owusu-Aduomi Botchwey C, Boateng AA, Brown R, et al. Guardians of health: exploring hand hygiene practices, knowledge and hurdles among public health nurses in Effutu municipality. Hospital Practices and Research 2023:224–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadivar M, Manookian A, Asghari F, et al. Ethical and legal aspects of patient’s safety: a clinical case report. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2017;10:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.S Altayyar S. Medical Devices and Patient Safety. JAPLR 2016;2. 10.15406/japlr.2016.02.00034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, et al. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017708. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Najjar S, Nafouri N, Vanhaecht K, et al. The relationship between patient safety culture and adverse events: a study in palestinian hospitals. Saf Health 2015;1. 10.1186/s40886-015-0008-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrahamson K, Hass Z, Morgan K, et al. The relationship between nurse-reported safety culture and the patient experience. J Nurs Adm 2016;46:662–8. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray L, J, Streagle S, et al. AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: User’s Guide. (Prepared by Westat, under Contract no.HHSA290201300003C). AHRQ Publication no.18-0036-EF (Replaces 04-0041, 15(16)-0049-EF).. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018. Available: https://www.ahrq.gov/sops/quality-patient-safety/patientsafetyculture/hospital/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pertierra LR, Hughes KA, Vega GC, et al. High resolution spatial mapping of human footprint across Antarctica and its implications for the strategic conservation of Avifauna. PLOS One 2017;12:e0168280. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghasemi M, Khoshakhlagh AH, Mahmudi S, et al. Identification and assessment of medical errors in the triage area of an educational hospital using the SHERPA technique in Iran. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2015;21:382–90. 10.1080/10803548.2015.1073431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaziri S, Fakouri F, Mirzaei M, et al. Prevalence of medical errors in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19. 10.1186/s12913-019-4464-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakemam E, Albelbeisi AH, Davoodabadi S, et al. The impact of nurses' perceptions of systems thinking on occurrence and reporting of adverse events: A Cross‐Sectional study. J Nurs Manag 2022;30:482–90. 10.1111/jonm.13524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricciardi W, L, Sheridan S, Tartaglia R. Textbook of patient safety and clinical risk management. 2021. Available: https://europepmc.org/books/n/spr9783030594039/?extid=36315766&src=med [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C-H, Yen C-D. Leadership and turnover intentions of Taiwan TV reporters: the moderating role of safety climate. Asian Journal of Communication 2015;25:255–70. 10.1080/01292986.2014.960877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yesilyaprak T, Demir Korkmaz F. The relationship between surgical intensive care unit nurses' patient safety culture and adverse events. Nurs Crit Care 2023;28:63–71. 10.1111/nicc.12611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otchi E, Bannerman C, Lartey S, et al. Patient safety Situational analysis in Ghana. Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management 2018;23:257–63. 10.1177/2516043518806366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell JD . Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwesimintsim Government Hospital . Health information records. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamanae T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis. London: John Weather Hill, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arabloo J, Rezapour A, EBADI FA, et al. Measuring patient safety culture in Iran using the hospital survey on patient safety culture (HSOPS): an exploration of survey Reliability and validity. 2012. Available: https://ijhr.iums.ac.ir/article_3826.html

- 27.Drolet AL, Morrison DG. Do We Really Need Multiple-Item Measures in Service Research? Journal of Service Research 2001;3:196–204. 10.1177/109467050133001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayuo J, Koduah AO. Pattern and outcomes of medical malpractice cases in Ghana: a systematic content analysis. Ghana Med J 2022;56:322–30. 10.4314/gmj.v56i4.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.EduCeleb . 83.5% fail Ghana’s teachers licensure. 2023. Available: https://educeleb.com/83-5-fail-ghanas-teacher-licensure-exam/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statista . International poverty rate in Ghana from 2017 to 2022. 2022. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1222084/international-poverty-rate-in-ghana/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-073190supp001.pdf (362.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.