Abstract

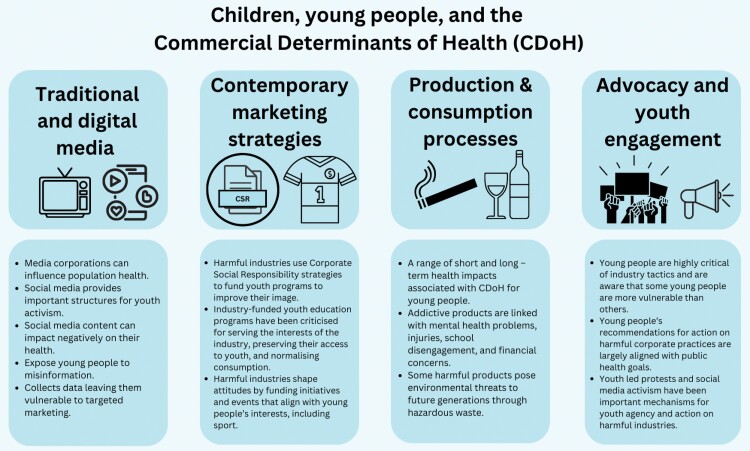

The commercial determinants of health (CDoH) have a significant impact on the health and well-being of children and young people (subsequently referred to as young people). While most research has focused on the influence of harmful industry marketing on young people, more recent CDoH frameworks have emphasized that a range of commercial systems and practices may influence health and well-being. Focusing on the impact of traditional and digital media, contemporary marketing strategies and corporate production and consumption processes, the following article outlines the impact of the CDoH on the health and wellbeing of young people. The article also provides evidence about how young people conceptualize the impact of corporate actors on health, and their involvement in advocacy strategies to respond. The article recommends that when collaborating with young people to understand the impacts of and responses to the CDoH, we should seek to diversify investigations towards the impact of a range of corporate tactics, systems and structures, rather than simply focusing on the impacts of advertising. This should include considering areas and priorities that young people identify as areas for action and understanding why some young people are more vulnerable to commercial tactics than others. Youth are powerful allies in responding to the CDoH. Public health and health promotion stakeholders could do more to champion the voices of young people and allow them to be active participants in the decisions that are made about harmful commercial practices and health.

Keywords: commercial determinants of health, children, young people, public health

Graphical Abstract

CONTRIBUTION TO HEALTH PROMOTION.

This article discusses the commercial determinants of health (CDoH) and the impact they have on young people.

Research into the CDoH and young people has mostly focused on the influence of harmful industry advertising.

Further research exploring broader tactics such as corporate social responsibility, is needed to understand how these strategies may feature and influence young people.

Children and young people are powerful advocates for their own health and well-being and need to be given the opportunity to be a part of the decisions that are made to protect them from commercial tactics.

DEVELOPMENTS IN COMMERCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH (CDoH) SCHOLARSHIP

Health is complex and political and requires public health and health promotion to be responsive to the range of factors that exist outside of the individual and that are vectors for poor health and well-being (Thomas and Daube, 2023; van Schalkwyk et al., 2021a). Over the last decade, there has been an increased global focus on the impact of commercial practices on the health and well-being of populations. Commercial determinants of health (CDoH) scholarship—interlinked with the social (Marmot and Bell, 2019) and political (Kickbush, 2015) determinants of health—has helped to provide a new theoretical lens on health equity, moving beyond biomedical and behavioural models of health and disease (Freudenberg, 2023).

Until recently, those working in the CDoH have mostly investigated the range of tactics that health-harming industries (such as the tobacco, alcohol, ultra-processed food, fossil fuel and commercial gambling industries) use to promote their products, increase profits and prevent meaningful regulatory reforms that would protect health and well-being (Gilmore et al., 2023, Lee, 2023). Sometimes called the ‘corporate playbook’, this has included tactics such as the impact of commercial marketing practices (Thomas et al., 2023b); the influence of framing on how the public view responsibility for engagement with harmful products (Casswell, 2013; van Schalkwyk et al., 2021b); corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies (Mialon and McCambridge, 2018); industry influence over scientific research (Fabbri et al., 2018; Vidaña-Perez et al., 2023); the influence of political donations (Johnson and Livingstone, 2021); and lobbying (McCambridge et al., 2014).

Researchers have recognized that the current research focus on the tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food industries has been understandable given the significant health and social burdens that they cause to communities (Gilmore et al., 2023; Lacy‐Nichols et al., 2023). However, newer industries such as vaping and online commercial gambling (Thomas et al., 2023a), as well as the fossil fuel (Friel et al., 2023) and firearm industries (Maani et al., 2020), operate from a similar playbook and utilize a range of novel practices and promotions to diversify and expose a new generation of consumers to their products. Furthermore, recent frameworks have recognized that the CDoH encompasses much more than harmful industry practices (Lee et al., 2022) and include the ‘systems, practices, and pathways through which commercial actors drive health and equity’ (Gilmore et al., 2023, p. 1195). Scholarship has expanded to investigate the role that structure and agency may play in enabling and supporting, or challenging corporate practices (Lee et al., 2022), including the role that governments play in intervening between these practices and health outcomes (Karreman et al., 2023). These are important areas of focus for the public health and health promotion communities, given the emphasis in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion on equity and social justice, and the call in the Charter for policymakers to be ‘aware of the health consequences of their decisions and to accept their responsibilities for health’ (World Health Organization, 1986, p. 2). The focus on equity, agency and structure in recent CDoH frameworks also provides an important lens through which to investigate how corporate practices (and responses to these) may impact different population groups in different ways (Friel et al., 2023). For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, researchers have argued that investigations into the CDoH must move beyond harmful products, towards research that examines the impacts of extractive activities, urbanization, trade liberalization and commercialization in health systems (Loewenson et al., 2022).

Just as with the social determinants of health, some populations are clearly more vulnerable to the impacts of corporate practices than others (McCarthy et al., 2023a). The Lancet Commission on a Future for the World’s Children argued that the CDoH poses significant threats to the health and well-being of children and that mechanisms are needed to amplify their voices and skills to ensure a healthy and sustainable future for people and the planet (Clark et al., 2020). Importantly, children and young people (subsequently referred to as young people) are not a homogenous group, and some young people are much more vulnerable than others, including First Nations and Indigenous children (Eisenkraft Klein and Shawanda, 2023), those from low socio-economic backgrounds (Mallol et al., 2021) and girls (McCarthy et al., 2023a).

To date, there have been few attempts to synthesize new areas of research, which consider the impact of the CDoH on the health of young people. The following article aims to address this gap by considering areas of CDoH research that may be particularly relevant to young people. We have focused on four areas: (i) the potential impact of traditional and digital media as a CDoH; (ii) the impact of contemporary marketing practices; (iii) the risks associated with corporate consumption and production practices; and (iv) the involvement of young people in advocacy initiatives as a way of responding to the CDoH.

THE IMPACT OF TRADITIONAL AND DIGITAL MEDIA AS A CDoH

The commercial practices of the media and more recently social media industries are a significant CDoH (Zenone et al., 2023). The activities of media corporations can influence population health and well-being (Brown and Witherspoon, 2002), including the role they play in framing health issues (Weishaar et al., 2016). Social media sites have become central to how young people connect and socialize, express their creativity, become engaged in debates and discussions and form their identities (Juvalta et al., 2023; Lyons et al., 2023). For the health promotion and public health communities, they have also provided unique ways to connect with young people (Ferretti et al., 2023; McCashin and Murphy, 2023; Taba et al., 2023), and have been powerful platforms to motivate activism and advocacy around important health and social issues, such as the climate crisis (Boulianne et al., 2020; Knupfer et al., 2023). Social media platforms have provided important structures for strengthening young people’s agency and voice in counter-framing corporate and government narratives, and in inspiring collective global action on important health and social issues (Molder et al., 2022).

However, there are also risks associated with the information that young people are exposed to through the media which may negatively impact their health and well-being—including the marketing of products that may be harmful to their health (Clark et al., 2020; Soraghan et al., 2023). Multiple studies have shown that the content that young people consume on social media platforms may contribute to heightened body image concerns (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2022) and mental health issues (particularly for girls) (Twenge et al., 2022). While new media platforms have enabled young people to easily access information about their health and well-being, it may also expose them to misinformation and disinformation based on a range of political ideologies that are difficult for them to navigate (Howard et al., 2021; Juvalta et al., 2023).

Data that is collected about young people via new media platforms is also central to helping industries target them with a range of products and ‘dark’ or covert marketing that may be harmful to their health (VicHealth, 2022). In particular, concerns have been raised about how social media may be used by harmful industries to target young people in lower-and-middle income countries (LMICs) (Bankole et al., 2023). Exposure to tobacco content through traditional and social media platforms is associated with youth smoking behaviours (Nunez-Smith et al., 2010), including lifetime use, past 30-day use and susceptibility to tobacco use among those who do not smoke (Donaldson et al., 2022). Similarly, exposure to alcohol marketing across different media channels can increase the likelihood that a young person will initiate or increase their alcohol use (Anderson et al., 2009). Newer social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram have come under particular scrutiny for exposing young people to marketing for harmful products such as gambling, with a lack of regulatory compliance associated with new forms of marketing on these platforms, such as influencer promotions (McCarthy et al., 2023b; Silver et al., 2023).

Social media platforms have also enabled health-harming industries to create new mechanisms for directly engaging youth in their marketing activities, including using challenges, encouraging young people to tag friends and share content with social network members in posts and creating user-generated content (Bankole et al., 2023; Brooks et al., 2022). Young people are also exposed to promotions for products that they are not able to ‘legally’ consume. For example, while young people are not able to legally gamble in most countries until the age of 18 years, they report seeing marketing for gambling products on a range of social media platforms, including YouTube, Snapchat and Instagram (Pitt et al., 2022a). These platforms have also enabled the industry to diversify from traditional young male markets to promote a range of female friendly campaigns on platforms such as TikTok designed to engage young women in gambling (McCarthy et al., 2023b).

THE IMPACT OF CONTEMPORARY MARKETING STRATEGIES ON YOUNG PEOPLE

To date much of the existing research into the impact of harmful industry practices on young people has focused on the impact of traditional forms of advertising such as commercial break advertising (Duke et al., 2014; Pitt et al., 2017; Pourmoradian et al., 2020; Winter et al., 2008). New definitions of marketing practices have included a much broader range of promotional strategies including promotions and incentives, and public relation activities such as CSR (Thomas et al., 2023b). Here we provide several examples to highlight the importance of investigating how corporations may use CSR strategies to soften perceptions of risk, engage and feature young people and build brand loyalty. CSR is a marketing strategy that aims to improve a company’s image within the community, divert attention from the negative impacts of their products, influence policymaking and prevent regulatory reform (Thomas et al., 2023a; Thomas et al., 2023b). While CSR strategies are diverse, many have a specific focus on young people. Examples include British American Tobacco initiatives in Malawi to ‘eliminate’ child labour in tobacco growing practices (Otañez et al., 2006); PepsiCo’s Refresh project which donated branded products to a range of youth initiatives including sporting programs (Dumbili and Odeigah, 2023); Nigeria Breweries running employment and skills training ‘empowerment’ programs for young people and women to respond to Sustainable Development Goal 8 relating to inclusive and sustainable economic growth (Otañez et al., 2006); Shell Globals’ NXplorer program which helps young people ‘learn how to address the complex challenges faced by the world and to do something about them’ (Shell Global, n.d.; Shell NXplorers, 2018); and a £10 million donation from the Betting and Gaming Council UK to fund gambling charity YGAM and treatment provider GamCare to deliver the ‘Young People’s Gambling Harm Prevention Programme’ (BGC, 2023).

While some of these initiatives might appear to be beneficial, Dorfman et al. (2012, p. 4) argue with specific reference to soda companies that CSR tactics are used to ‘tout their concern for the health and well-being of youth while simultaneously cultivating brand loyalty’. Analyses of tobacco industry documents found that the aim of youth education programs was not to reduce youth smoking rates but to ‘serve the industry’s political needs by preventing effective tobacco control legislation, …preserving the industry’s access to youths, …and preserving the industry’s influence with policy makers’ (Landman et al., 2002, p. 917). Gambling and alcohol industry-funded youth education programs have also been criticized by researchers for serving their own interests by effectively diverting attention from the harmful aspects of the products and services they promote, and normalizing the consumption of these products (van Schalkwyk et al., 2022a,b).

Corporations may also shape social and cultural attitudes and build corporate support among young people through funding initiatives and events that align with their interests. Historically, tobacco companies have sponsored music festivals and focused marketing at bars and nightclub events to embed their brand within youth culture, a tactic that has also been seen from e-cigarette brands (Tobacco Tactics, 2021; Truth Initiative, 2018). Alcohol companies have sponsored popular cultural events to attract the attention of young people (Yoon and Lam, 2013). The fossil fuel industry sponsored school-based maths and science education programs, including Exxon Mobile’s Education Alliance in the USA (Exxon, 2023), and Rio Tinto invested $2 million to provide access to quality early childhood education in the Pilbara region of Western Australia (RioTinto, 2022).

Finally, sports sponsorship remains a well-established and effective form of indirect marketing for harmful industries to influence the consumption behaviours of young people. Sports sponsorship has contributed to the increased uptake of smoking among young people (Tobacco Tactics, 2022), normalized gambling as a common part of sport (Pitt et al., 2016; Djohari et al., 2019; Pitt et al., 2023) and has positively influenced young people’s attitudes towards unhealthy food and beverage sponsors (Cancer Council WA, 2023). BP Australia sponsored the Indigenous Nationals sporting event, including providing scholarships for student athletes to ‘support their academic and athletic endeavours’ (BP Australia, 2023). Importantly, research shows that young people may be less critical of the sponsorship activities of harmful industries as compared to their commercial activities, believing that sponsorship provides sporting teams and related organizations with important financial benefits (Pitt et al., 2022b).

THE RISKS OF CORPORATE PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION PROCESSES ON THE HEALTH OF YOUNG PEOPLE

There are a range of short- and long-term health impacts associated with the CDoH for young people. The impacts of addictive products such as alcohol and gambling include mental health problems (Ryan et al., 2019), injuries (Chikritzhs and Livingston, 2021), disengagement from school (Ssewanyana and Bitanihirwe, 2018) and financial concerns (Livazović and Bojčić, 2019). Ultra-processed foods contribute to a range of non-communicable diseases among young people across the world (Nardocci et al., 2019). Importantly while there have been significant reductions in the initiation and continuation of smoking in adolescents, rates of smoking in LMICs and among Indigenous young people remain comparatively high (Xi et al., 2016; Heris et al., 2020). Novel products such as vaping have also created a new range of health risks for young people (Jonas, 2022; Khan et al., 2023), and the true extent of the health harms posed by these and other new products such as online gambling may not be seen for many years to come.

We also note that products such as tobacco and vaping pose environmental threats to future generations through increased hazardous wastes (Pourchez et al., 2022), although these industries have utilized greenwashing and ‘environmental consciousness’ tactics to minimize the perceptions of these risks (Heley et al., 2022). Young people are particularly at risk of the harms caused by extractive industries, due to instances of child labour, displacement from housing, exposure to pollution and waste, as well as the damage caused to the well-being of the planet (DFAT, 2017). The significant environmental impacts associated with greenhouse gas and carbon emissions will arguably jeopardize the ability of young people to live on a healthy planet (Clark et al., 2020).

YOUNG PEOPLE ARE SUPPORTIVE OF RESTRICTIONS ON THE PRACTICES OF HARMFUL CORPORATIONS

Much less research has investigated young people’s views about the CDoH (Soraghan et al., 2023). Research with young people about the commercial determinants of the climate crisis (Arnot et al., 2023c), gambling (Pitt et al., 2022b), alcohol (Aiken et al., 2018; Beccaria et al., 2019), tobacco and vaping (MacGregor et al., 2020; Pettigrew et al., 2022) and harmful commercial marketing (Soraghan et al., 2023) has documented that they are highly critical of industry tactics and aware of the influence of profit motives on their resistance to reforming their practices. Young people are skeptical that the ‘soft’ strategies used by harmful corporations will make a difference to health and social harms without strong government intervention (Arnot et al., 2023b). They are also aware of health equity issues, and are concerned that some young people are more vulnerable to the tactics of harmful industries than others (Arnot et al., 2023b; Soraghan et al., 2023). However, there is still limited research that has explored the impact of the CDoH on specific groups of young people such as those from LMICs and Indigenous youth, and how they think these determinants should be addressed.

Young people’s recommendations for action are largely aligned with public health and health promotion goals. For example, in a New Zealand study, young people were asked what they would do about junk food marketing if they were Prime Minister for a day, with responses ranging from complete marketing bans, to changes to the content of marketing to ensure it was more honest and less deceptive (Signal et al., 2019). A recent consultation with young people about the range of policies that could be used to counter harmful marketing also found that they were particularly concerned about the lack of regulation of marketing on digital platforms, including the presence of misleading marketing that created a perception that some harmful products were health promoting (Soraghan et al., 2023). Similar recommendations have been made by young people in relation to gambling. Young people aged 11–17 years recommended reducing the accessibility and availability of gambling products, placing restrictions and bans on marketing, untangling the relationship between gambling and sport, making products safer and counteracting the positive messages about gambling (Pitt et al., 2022b). Importantly, even when young people have a high social acceptance of novel products such as vapes, most are supportive of comprehensive government regulations of these products (Gorukanti et al., 2017).

YOUNG PEOPLE ARE INCREASINGLY INVOLVED IN ADVOCACY INITIATIVES TO TACKLE HARMFUL INDUSTRIES

Young people are increasingly involved in a range of advocacy initiatives demanding policy action on harmful industries. Examples include the work of young people in exposing the tobacco industry and more recently vaping tactics as part of the US-based (Truth Initiative, 2023), as well as action on unhealthy food marketing and access to healthy food through Bite Back in the UK (Bite Back, 2023). Another example, has been the powerful youth movement on climate justice, including Seed Mob, Australia’s first Indigenous-led youth group aiming to address climate injustices, which highlights the important role that First Nations youth can play in holding governments and industry accountable for a ‘just and sustainable future’ (Seed, n.d). Youth-led protests and social media activism have also been important mechanisms for youth agency and action on climate (Arnot et al., 2023a), including a range of events and organizations inspired by Greta Thunberg’s activism like the now global School Strike 4 Climate (Boulianne et al., 2020), Fridays for Future (Fridays For Future, 2023) and the UK founded Extinction Rebellion (Extinction Rebellion, n.d.); as well as gun control through the USA March For Our Lives student movement (Kelly, 2021; King, 2021; Zoller and Casteel, 2022). These forms of action may provide important opportunities for youth to be engaged in action on other CDoH.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH AND HEALTH PROMOTION COMMUNITIES CAN STRENGTHEN YOUTH ENGAGEMENT IN THE CDoH

Addressing the CDoH and their impacts on young people must involve transformative approaches that not only listen to their views but engages them in decision making and policy action. We recommend three areas for focus:

1) CDoH researchers should collaborate with young people to investigate how a range of different corporate tactics, systems and structures may impact the health and well-being of young people. This involves considering the issues that young people see as the most important priorities in their own lives. While the impacts of new media platforms and mis/disinformation are areas of concern, we should also examine how new media platforms may increase the agency of young people to respond to the CDoH. Importantly, researchers should work with young people to define research agendas and areas for action, and should be mindful that the issues that young people prioritize may change over time.

2) While CDoH scholarship on young people is advancing, it is concerning that there has been so little research that has sought to directly engage young people (particularly those most at risk) in discussions about the CDoH, and the range of strategies that they think may be used to respond. There is much to be learned from non-governmental organizations working in these areas, who have engaged and supported youth to develop powerful youth-centred movements that have exposed industry tactics and argued for policy reform.

3) We should be careful about the potential ‘youthwashing’ of strategies to respond to the CDoH. This is where young people’s voices are used or platformed without initiatives that act on their key concerns or suggestions for action (Arnot et al., 2023a; The Climate Reality Project, 2023). Mechanisms should be developed which engage young people in meaningful democratic participation in the decisions that are made about action on the CDoH, recognizing their agency as important stakeholders in the decisions that may impact their health and well-being.

There is much to be learned from young people about how we can respond more effectively to the CDoH. Advancing CDoH scholarship, advocacy and action must involve transformational change in how we engage and include young people to tackle the powerful vested interests of harmful and predatory industries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Professor Samantha Thomas and Emeritus Professor Mike Daube for their guidance and contribution to the development of this article.

Contributor Information

Hannah Pitt, Institute for Health Transformation, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, 1 Gheringhap Street, Geelong, Victoria 3220, Australia.

Simone McCarthy, Institute for Health Transformation, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, 1 Gheringhap Street, Geelong, Victoria 3220, Australia.

Grace Arnot, Institute for Health Transformation, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, 1 Gheringhap Street, Geelong, Victoria 3220, Australia.

FUNDING

This article was supported by Dr Hannah Pitt’s VicHealth Early Career Research Fellowship and an ARC Discovery Grant (DP 210101983).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

H.P. has received research funding from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Scheme, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, the New South Wales Office of Responsible Gambling, VicHealth and Deakin University. She is currently on the editorial board of Health Promotion International and was not involved in the review process nor in any decision making on the manuscript. S.M. has received research funding from the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, VicHealth and Deakin University. She is currently social media coordinator of Health Promotion International and was not involved in the review process nor in any decision making on the manuscript. G.A. has received research funding from Deakin University and VicHealth. She is currently co-social media coordinator of Health Promotion International and was not involved in the review process nor in any decision making on the manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.P.: Contributed to the conceptualization, drafting and critical revisions of the manuscript. S.M.: Contributed to the conceptualization and critical revisions of the manuscript. G.A.: Contributed to the conceptualization, drafting and critical revisions of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aiken, A., Lam, T., Gilmore, W., Burns, L., Chikritzhs, T., Lenton, S.et al. (2018) Youth perceptions of alcohol advertising: are current advertising regulations working? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42, 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P., de Bruijn, A., Angus, K., Gordon, R. and Hastings, G. (2009) Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 44, 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot, G., Pitt, H., McCarthy, S., Collin, P. and Thomas, S. (2023a) Supporting young people as genuine political actors in climate decision making. Health Promotion International, 38, 1–4, 10.1093/heapro/daad148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot, G., Thomas, S., Pitt, H. and Warner, E. (2023b) Australian young people’s perspectives about the political determinants of the climate crisis. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot, G., Thomas, S., Pitt, H. and Warner, E. (2023c) Australian young people’s perceptions of the commercial determinants of the climate crisis. Health Promotion International, 38, 1–12, 10.1093/heapro/daad058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankole, E., Harris, N., Rutherford, S. and Wiseman, N. (2023) A systematic review of the adolescent‐directed marketing strategies of transnational fast food companies in low and middle income countries. Obesity Science & Practice, 9, 670–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beccaria, F., Molinengo, G., Prina, F. and Rolando, S. (2019) Young people, alcohol and norms: Italian young people’s opinions and attitudes towards alcohol regulation. Young, 27, 395–413. [Google Scholar]

- BGC. (2023) Teaching Young People about Problem Gambling. https://bettingandgamingcouncil.com/annual-review/teaching-young-people-about-problem-gambling (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Bite Back. (2023) BiteBack2030. https://www.biteback2030.com/ (26 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Boulianne, S., Lalancette, M. and Ilkiw, D. (2020) ‘School Strike 4 Climate’: social media and the international youth protest on climate change. Media and Communication, 8, 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- BP Australia. (2023) Indigenous Nationals. https://www.bp.com/en_au/australia/home/community/community-partnerships/indigenous-nationals-.html (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Brooks, R., Christidis, R., Carah, N., Kelly, B., Martino, F. and Backholer, K. (2022) Turning users into ‘unofficial brand ambassadors’: marketing of unhealthy food and non-alcoholic beverages on TikTok. BMJ Global Health, 7, e009112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. D. and Witherspoon, E. M. (2002) The mass media and American adolescents’ health. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Council WA. (2023) Junk Food in Sport: It’s JUST not Cricket. Western Australia, Australia. https://cancerwa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Advocacy-Report-Junk-Food-in-Sport-Its-Just-Not-Cricket_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Casswell, S. (2013) Vested interests in addiction research and policy. Why do we not see the corporate interests of the alcohol industry as clearly as we see those of the tobacco industry? Addiction, 108, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikritzhs, T. and Livingston, M. (2021) Alcohol and the risk of injury. Nutrients, 13, 2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choukas-Bradley, S., Roberts, S. R., Maheux, A. J. and Nesi, J. (2022) The perfect storm: a developmental–sociocultural framework for the role of social media in adolescent girls’ body image concerns and mental health. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 25, 681–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H., Coll-Seck, A. M., Banerjee, A., Peterson, S., Dalglish, S. L., Ameratunga, S.et al. (2020) A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 395, 605–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DFAT. (2017) DFAT Child Protection Guidance Note: Extractive Industries. Australia. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/Extractive%20Industries.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Djohari, N., Weston, G., Cassidy, R., Wemyss, M. and Thomas, S. (2019) Recall and awareness of gambling advertising and sponsorship in sport in the UK: a study of young people and adults. Harm Reduction Journal, 16, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, S. I., Dormanesh, A., Perez, C., Majmundar, A. and Allem, J. -P. (2022) Association between exposure to tobacco content on social media and tobacco use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 176, 878–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman, L., Cheyne, A., Friedman, L. C., Wadud, A. and Gottlieb, M. (2012) Soda and tobacco industry corporate social responsibility campaigns: how do they compare. PLoS Medicine, 9, e1001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke, J. C., Lee, Y. O., Kim, A. E., Watson, K. A., Arnold, K. Y., Nonnemaker, J. M.et al. (2014) Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults. Pediatrics, 134, e29–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbili, E. W. and Odeigah, O. W. (2023) Alcohol industry corporate social responsibility activities in Nigeria: implications for policy. Journal of Substance Use, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenkraft Klein, D. and Shawanda, A. (2023) Bridging the commercial determinants of Indigenous health and the legacies of colonization: a critical analysis. Global Health Promotion, 10.1177/17579759231187614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extinction Rebellion. (n.d.) This is an Emergency. https://rebellion.global/ (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Exxon. (2023) Educational Alliance. https://www.exxon.com/en/educational-alliance (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Fabbri, A., Lai, A., Grundy, Q. and Bero, L. A. (2018) The influence of industry sponsorship on the research agenda: a scoping review. American Journal of Public Health, 108, e9–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, A., Hubbs, S. and Vayena, E. (2023) Global youth perspectives on digital health promotion: a scoping review. BMC Digital Health, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg, N. (2023) Integrating social, political and commercial determinants of health frameworks to advance public health in the twenty-first century. International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services, 53, 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridays For Future. (2023) #Fridays for Future. https://fridaysforfuture.org/ (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Friel, S., Collin, J., Daube, M., Depoux, A., Freudenberg, N., Gilmore, A. B.et al. (2023) Commercial determinants of health: future directions. Lancet, 401, 1229–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, A. B., Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H. -J.et al. (2023) Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet, 401, 1194–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorukanti, A., Delucchi, K., Ling, P., Fisher-Travis, R. and Halpern-Felsher, B. (2017) Adolescents’ attitudes towards e-cigarette ingredients, safety, addictive properties, social norms, and regulation. Preventive Medicine, 94, 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heley, K., Czaplicki, L., Kennedy, R. D. and Moran, M. (2022) ‘Help Save The Planet One Bidi Stick At A Time!’: greenwashing disposable vapes. Tobacco Control, 31, 675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heris, C. L., Chamberlain, C., Gubhaju, L., Thomas, D. P. and Eades, S. J. (2020) Factors influencing smoking among indigenous adolescents aged 10–24 years living in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States: a systematic review. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 22, 1946–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P., Neudert, L., Prakash, N. and Vosloo, S. (2021) Digital misinformation/disinformation and children. UNICEF, New York. https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/media/2096/file/unicef-global-insight-digital-mis-disinformation-and-children-2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. and Livingstone, C. (2021) Measuring influence: an analysis of Australian gambling industry political donations and policy decisions. Addiction Research & Theory, 29, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, A. (2022) Impact of vaping on respiratory health. BMJ, 378, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvalta, S., Speranza, C., Robin, D., El Maohub, Y., Krasselt, J., Dreesen, P.et al. (2023) Young people’s media use and adherence to preventive measures in the ‘infodemic’: Is it masked by political ideology? Social Science & Medicine, 317, 115596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman, N., Huang, Y., Egan, N., Carters-White, L., Hawkins, B., Adams, J.et al. (2023) Understanding the role of the state in dietary public health policymaking: a critical scoping review. Health Promotion International, 38, 1–13, 10.1093/heapro/daad100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J. (2021) The youth voice: what does gun violence mean to us? In Dodson, N. (ed), Adolescent Gun Violence Prevention: Clinical and Public Health Solutions. Springer, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. M., Ahmed, S., Sarfraz, Z. and Farahmand, P. (2023) Vaping and mental health conditions in children: an umbrella review. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–11. 10.1177/11782218231167322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbush, I. (2015) The political determinants of health- 10 years on. BMJ, 350, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, T. (2021) Youth gun violence prevention organizing. In Crandall, M., Boone, S., Bronson, J. and Kessel, W. (eds), Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States. Springer, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Knupfer, H., Neureiter, A. and Matthes, J. (2023) From social media diet to public riot? Engagement with ‘greenfluencers’ and young social media users’ environmental activism. Computers in Human Behavior, 139, 107527. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy‐Nichols, J., Bentley, R. and Elshaug, A. G. (2023) Commercial determinants of human rights: for‐profit health care and housing. The Medical Journal of Australia, 219, 4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landman, A., Ling, P. M. and Glantz, S. A. (2002) Tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programs: protecting the industry and hurting tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 917–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K., Freudenberg, N., Zenone, M., Smith, J., Mialon, M., Marten, R.et al. (2022) Measuring the commercial determinants of health and disease: a proposed framework. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 52, 115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. (2023) Advancing the commercial determinants of health agenda. The Lancet, 401, 16–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livazović, G. and Bojčić, K. (2019) Problem gambling in adolescents: what are the psychological, social and financial consequences? BMC Psychiatry, 19, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenson, R., Godt, S. and Chanda-Kapata, P. (2022) Asserting public health interest in acting on commercial determinants of health in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a discourse analysis. BMJ Global Health, 7, e009271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A. C., Goodwin, I., Carah, N., Young, J., Moewaka Barnes, A. and McCreanor, T. (2023) Limbic platform capitalism: understanding the contemporary marketing of health-demoting products on social media. Addiction Research & Theory, 31, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Maani, N., Abdalla, S. M. and Galea, S. (2020) The firearm industry as a commercial determinant of health. American Journal of Public Health, 110, 1182–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, A., Delaney, H., Amos, A., Stead, M., Eadie, D., Pearce, J.et al. (2020) ‘It’s like sludge green’: young people’s perceptions of standardized tobacco packaging in the UK. Addiction, 115, 1736–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallol, J., Urrutia-Pereira, M., Mallol-Simmonds, M. J., Calderón-Rodríguez, L., Osses-Vergara, F. and Matamala-Bezmalinovic, A. (2021) Prevalence and determinants of tobacco smoking among low-income urban adolescents. Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology, 34, 60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. and Bell, R. (2019) Social determinants and non-communicable diseases: time for integrated action. BMJ, 364, l251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge, J., Hawkins, B. and Holden, C. (2014) Vested interests in addiction research and policy. The challenge corporate lobbying poses to reducing society’s alcohol problems: insights from UK evidence on minimum unit pricing. Addiction, 109, 199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, S., Pitt, H., Hennessy, M., Njiro, B. J. and Thomas, S. (2023a) Women and the commercial determinants of health. Health Promotion International, 38, 10.1093/heapro/daad076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, S., Pitt, H. and Thomas, S. (2023b) From TV to TikTok, young people are exposed to gambling promotions everywhere. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/from-tv-to-tiktok-young-people-are-exposed-to-gambling-promotions-everywhere-200067 (7 August 2023, date last accessed).

- McCashin, D. and Murphy, C. M. (2023) Using TikTok for public and youth mental health—a systematic review and content analysis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28, 279–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mialon, M. and McCambridge, J. (2018) Alcohol industry corporate social responsibility initiatives and harmful drinking: a systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 28, 664–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molder, A. L., Lakind, A., Clemmons, Z. E. and Chen, K. (2022) Framing the global youth climate movement: a qualitative content analysis of Greta Thunberg’s moral, hopeful, and motivational framing on instagram. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27, 668–695. [Google Scholar]

- Nardocci, M., Leclerc, B. -S., Louzada, M. -L., Monteiro, C. A., Batal, M. and Moubarac, J. -C. (2019) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue canadienne de sante publique, 110, 4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Smith, M., Wolf, E., Huang, H. M., Chen, P. G., Lee, L., Emanuel, E. J.et al. (2010) Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Substance Abuse, 31, 174–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otañez, M. G., Muggli, M. E., Hurt, R. D. and Glantz, S. A. (2006) Eliminating child labour in Malawi: a British American Tobacco corporate responsibility project to sidestep tobacco labour exploitation. Tobacco Control, 15, 224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, S., Miller, M., Santos, J. A., Brown, K., Morelli, G., Sudhir, T.et al. (2022) Young people’s support for various forms of e-cigarette regulation in Australia and the UK. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 110, 103858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., Thomas, S. L., Bestman, A., Stoneham, M. and Daube, M. (2016) ‘It’s just everywhere!’ Children and parents discuss the marketing of sports wagering in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 40, 480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., Thomas, S. L., Bestman, A., Daube, M. and Derevensky, J. (2017) What do children observe and learn from televised sports betting advertisements? A qualitative study among Australian children. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41, 604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., McCarthy, S., Rintoul, A. and Thomas, S. (2022a) The Receptivity of Young People to Gambling Marketing Strategies on Social Media Platforms. Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Victoria, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., Thomas, S. L., Randle, M., Cowlishaw, S., Arnot, G., Kairouz, S.et al. (2022b) Young people in Australia discuss strategies for preventing the normalisation of gambling and reducing gambling harm. BMC Public Health, 22, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., McCarthy, S. and Thomas, S. (2023) The impact of marketing on the normalisation of gambling and sport for children and young people. In McGee, D. and Bunn, C. (eds), Gambling and Sports in a Global Age. Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pourchez, J., Mercier, C. and Forest, V. (2022) From smoking to vaping: a new environmental threat? The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10, e63–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmoradian, S., Ostadrahimi, A., Bonab, A. M., Roudsari, A. H., Jabbari, M. and Irandoost, P. (2020) Television food advertisements and childhood obesity: a systematic review. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 91, 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RioTinto. (2022) Building Thriving Communities. Western Australia, Australia. https://www.bp.com/en_au/australia/home/community/community-partnerships/indigenous-nationals-.html. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, S. A., Kokotailo, P., Camenga, D. R., Patrick, S. W., Plumb, J., Quigley, J.et al. (2019) Alcohol use by youth. Pediatrics, 144, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seed. (n.d.) Seed. https://www.seedmob.org.au/our_story (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Shell Global. (n.d.) Education. https://www.shell.com/sustainability/communities/education.html (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Shell NXplorers. (2018) A New Way of Thinking. https://nxplorers.com/ (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Signal, L. N., Jenkin, G. L., Barr, M. B., Smith, M., Chambers, T. J., Hoek, J.et al. (2019) Prime minister for a day: children’s views on junk food marketing and what to do about it. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 132, 36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, N. A., Bertrand, A., Kucherlapaty, P. and Schillo, B. A. (2023) Examining influencer compliance with advertising regulations in branded vaping content on Instagram. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soraghan, M., Abdulkareem, T., Jennings, B., Boateng, J., Chavira Garcia, J., Chopra, V.et al. (2023) Harmful marketing by commercial actors and policy ideas from youth. Health Promotion International, 38, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewanyana, D. and Bitanihirwe, B. (2018) Problem gambling among young people in sub-Saharan Africa. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taba, M., Ayre, J., Freeman, B., McCaffery, K. and Bonner, C. (2023) COVID-19 messages targeting young people on social media: content analysis of Australian health authority posts. Health Promotion International, 38, 10.1093/heapro/daad034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Climate Reality Project. (2023) You’ve Heard of Greenwashing, But What is Youthwashing?https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/youve-heard-greenwashing-what-youthwashing (26 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Thomas, S., Cowlishaw, S., Francis, J., van Schalkwyk, M. C., Daube, M., Pitt, H.et al. (2023a) Global public health action is needed to counter the commercial gambling industry. Health Promotion International, 38, 10.1093/heapro/daad110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S. and Daube, M. (2023) New times, new challenges for health promotion. Health Promotion International, 38, 10.1093/heapro/daad012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S., Van Schalkwyk, M. C., Daube, M., Pitt, H., McGee, D. and McKee, M. (2023b) Protecting children and young people from contemporary marketing for gambling. Health Promotion International, 38, 1–14, 10.1093/heapro/daac194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Tactics. (2021) CSR: Arts & Culture. https://tobaccotactics.org/article/csr-arts-culture/ (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Tobacco Tactics. (2022) Football Sponsorship. https://tobaccotactics.org/article/football-sponsorship/ (29 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Truth Initiative (2023) Our Mission. https://truthinitiative.org/who-we-are/our-mission (26 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Truth Initiative. (2018) How Tobacco Companies Use Experiential Marketing. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/tobacco-industry-marketing/how-tobacco-companies-use-experiential-marketing (29 June 2023, date last accessed).

- Twenge, J. M., Haidt, J., Lozano, J. and Cummins, K. M. (2022) Specification curve analysis shows that social media use is linked to poor mental health, especially among girls. Acta Psychologica, 224, 103512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., Hawkins, B. and Petticrew, M. (2022) The politics and fantasy of the gambling education discourse: an analysis of gambling industry-funded youth education programmes in the United Kingdom. SSM—Population Health, 18, 101122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., Maani, N., Cohen, J., McKee, M. and Petticrew, M. (2021a) Our postpandemic world: what will it take to build a better future for people and planet? The Milbank Quarterly, 99, 467–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., Maani, N., McKee, M., Thomas, S., Knai, C. and Petticrew, M. (2021b) ‘When the Fun Stops, Stop’: an analysis of the provenance, framing and evidence of a ‘responsible gambling’ campaign. PLoS One, 16, e0255145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., Petticrew, M., Maani, N., Hawkins, B., Bonell, C., Katikireddi, S. V.et al. (2022) Distilling the curriculum: an analysis of alcohol industry-funded school-based youth education programmes. PLoS One, 17, e0259560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VicHealth. (2022) Dark Marketing Tactics of Harmful Industries Exposed by Young Citizen Scientists. VicHealth, Victoria, Australia. https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/resources/resource-download/citizen-voices-against-harmful-marketing (29 September 2023, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- Vidaña-Perez, D., Reynales-Shigematsu, L. M., Antonio-Ochoa, E., Ávila-Valdez, S. L. and Barrientos-Gutiérrez, I. (2023) The fallacy of science is science: the impact of conflict of interest in vaping articles. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 46, e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weishaar, H., Dorfman, L., Freudenberg, N., Hawkins, B., Smith, K., Razum, O.et al. (2016) Why media representations of corporations matter for public health policy: a scoping review. BMC Public Health, 16, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter, M. V., Donovan, R. J. and Fielder, L. J. (2008) Exposure of children and adolescents to alcohol advertising on television in Australia. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1986) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, 1986. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/349652/WHO-EURO-1986-4044-43803-61677-eng.pdf (14 November 2023, date last accessed).

- Xi, B., Liang, Y., Liu, Y., Yan, Y., Zhao, M., Ma, C.et al. (2016) Tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in young adolescents aged 12–15 years: data from 68 low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Global Health, 4, e795–e805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S. and Lam, T. -H. (2013) The illusion of righteousness: corporate social responsibility practices of the alcohol industry. BMC Public Health, 13, 630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenone, M., Kenworthy, N. and Maani, N. (2023) The social media industry as a commercial determinant of health. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 12, 6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoller, H. M. and Casteel, D. (2022) #March for our lives: health activism, diagnostic framing, gun control, and the gun industry. Health Communication, 37, 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]