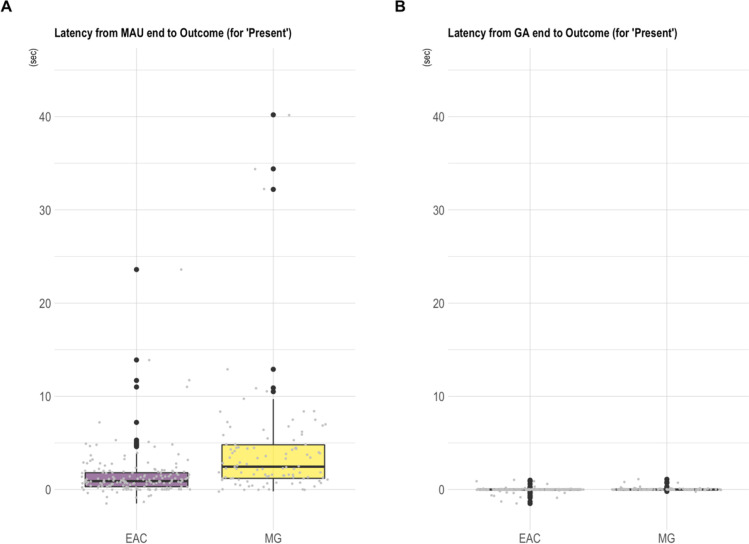

Fig. 5.

Worked example 2.1: Mountain gorilla and chimpanzee recipient latencies to (behaviourally) respond to a signaller’s request to be groomed using the ‘present’ gesture action (n = 281 successful communications). Note. Boxplots showing the response waiting times (latencies to respond) in East African chimpanzees (EAC; n = 177 communications, n = 70 signallers) and mountain gorillas (MG; n = 104 communications, n = 27 signallers) for the gesture action ‘present’ and the outcome ‘grooming’ (total: n = 281 communications) when considering either A the minimum action unit (MAU) end point or B the gesture action (GA) end point as the start of response waiting (see Fig. 4 for a conceptual visualisation of different response latency measurements). Mountain gorillas seem to be slower to respond to grooming requests than East African chimpanzees. Note that a single value (the maximum value of 78.1 s for the mountain gorillas) is not visually represented on the graph (though not omitted from the scaling) for the purpose of better resolution. As the ‘present’ gesture action has the characteristic of being held in place until the goal is fulfilled (in successful communications) there is unsurprisingly little variation in the gesture action to outcome latency (graph B), which is close to 0 in both species (MG GA.Outcome latency range = – 0.2–1.1; EAC GA.Outcome latency range = – 1.5–1.0 s). The negative latencies result from instances where the recipient already responded to the gesture before the respective action phase (MAU and/or GA) was completed