Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the impact of pre- and peri-operative factors on postlinguistic adult cochlear implant (CI) performance and design a multivariate prediction model.

Study Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Setting:

Tertiary referral center.

Patients & Interventions:

239 postlinguistic adult CI recipients

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Speech-perception testing (CNC, AzBio in noise +10-dB SNR) at 3-, 6- and 12-months postoperatively; Electrocochleography-total response (ECochG-TR) at the round window before electrode insertion

Results:

ECochG-TR strongly correlated with CNC word score at 6-months (r = 0.71, p <0.0001). A multivariable linear regression model including age, duration of hearing loss, angular insertion depth, and ECochG-TR did not perform significantly better than ECochG-TR alone in explaining the variability in CNC. AzBio in noise at 6 months had moderate linear correlations with MoCA (r = 0.38, p <0.0001) and ECochG-TR (r = 0.42, p <0.0001). ECochG-TR and MoCA, and their interaction, explained 45.1% of the variability in AzBio in noise scores.

Conclusions:

This study uses the most comprehensive dataset to date to validate ECochG-TR as a measure of cochlear health as it relates to suitability for CI stimulation, and it further underlies the importance of the cochlear neural substrate as the main driver in speech perception performance. Performance in noise is more complex and requires both good residual cochlear function (ECochG-TR) and cognition (MoCA). Other demographic, audiologic and surgical variables are poorly correlated with CI performance suggesting that these are poor surrogates for the integrity of the auditory substrate.

Keywords: cochlear implants, cochlear implantation, electrocochleography, ECochG, MoCA score, speech-perception performance

INTRODUCTION:

Cochlear implants (CIs) are an effective intervention for restoring hearing in patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss who do not benefit sufficiently from hearing aids (1–3). However, speech perception outcomes have been variable and unpredictable (4–7), which makes it challenging to manage expectations, identify cases needing early additional aural rehabilitation, or determine if the device functions optimally for each individual recipient.

Early research indicated that duration of deafness was the most critical demographic factor influencing speech perception outcomes (4,8–10). However, as prolonged deafness has become less common, its predictive value has diminished (9,11). While various demographic and audiological factors, such as residual hearing prior to implantation (12), age (10), and surgical factors (9–11,13), can impact speech perception outcomes, their overall influence is modest. For instance, a recent multicenter study of 2,735 adult CI users found that 17 pre- and post-surgical factors explained only 12 to 21% of the variance (R2) (14).

To better understand the variability in CI performance, neurocognitive factors involving central mechanisms or “top-down” processing must be considered. These factors involve skills necessary for acquiring knowledge, manipulating information, and reasoning, and are necessary for active and effortful decoding of the distorted speech signal output from a CI, which is “bottom-up” processing (15–17). Consideration of cognitive measures (such as working memory, attention, and executive functions), speech perception abilities in challenging noise environments, linguistic proficiency, auditory training post-implantation, and even music perception skills could shed light on these top-down processing influences. Despite the potential significance of these factors, inconsistent findings across studies with varying designs and methodologies have limited our understanding of this association (18,19).

Electrocochleography (ECochG) is a promising method for assessing cochlear function in CI recipients. It measures cochlear electrical signals in response to sound and has potential in predicting speech perception outcomes. The round window (RW) ECochG response prior to implantation can explain 40 to 50% of the variation in CI-alone speech perception outcomes in quiet at 3- or 6-months, highlighting the peripheral auditory system’s importance in CI outcomes (20–24). Furthermore, ECochG response alone is a better predictor of outcomes than pre-insertion factors such as duration of hearing loss, age, and preoperative residual hearing (21).

By combining the ECochG response with measurements of angular insertion depth from post-implantation x-rays and analysis of array design, it’s possible to account for as much as 72% of variability in speech perception performance in quiet (25). Our recent research also shows that combining postoperative ECochG response at 3-months with Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores can explain almost 60% of variability in performance in noisy environments (24). These findings emphasize the importance of both central (MoCA) and peripheral (ECochG) mechanisms for achieving optimal CI performance in background noise. Although ECochG response is a significant predictor of speech perception performance, considering multiple factors is crucial for predicting and optimizing outcomes following cochlear implantation.

Previous work that aimed to predict CI performance in background noise using the combination of MoCA score and ECochG response was conducted on a small sample size (n = 35) and only utilized postoperative measurements of the ECochG response (24). In this study, we present the most recent analysis of ECochG data, as measured at the RW prior to implant insertion, and speech perception outcomes in both quiet and noisy environments. The aim of the present study was to confirm the prior ECochG models of auditory performance and to fully assess the effect of various demographic, audiologic, and surgical factors on a large sample of CI recipients. We hypothesized that a model combining the ECochG response, angular insertion depth (AID), array design, and MoCA score would provide a better prediction of speech perception outcomes compared to using any individual factor alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Participants and Inclusion Criteria

This prospective study included post-lingually deafened adults who received CIs and intraoperative ECochG after passing medical and audiologic evaluations. The IRB of Washington University in St. Louis approved the study, and all participants provided informed consent. The study included adult CI recipients of any age and etiology of deafness, excluding non-native English speakers, those with inner ear malformations, and those with non-patent external auditory canals or who underwent CI revision surgery. Candidates for cochlear implantation were selected based on a combination of factors including severity of hearing loss, measures of hearing aid benefit, overall health status, and their motivation and ability to comply with the post-operative rehabilitation plan. Participants received either a lateral wall or pre-curved array with 22 electrode contacts by Cochlear Limited (Sydney, Australia): the Slim 20 lateral wall array (CI624) or either the slim perimodiolar electrode (CI632) or perimodiolar electrode (CI612) pre-curved arrays. All patients used the N7 processor.

Round Window (RW) ECochG Recordings

Acoustically-evoked ECochG responses were obtained from the RW of CI recipients before implant array insertion. An ER3–14A foam earplug (Etymotic, Elk Grove Village, IL) connected to a sound tube and speaker served as the acoustic stimulus. The CI implant’s ground electrode was used as the recording electrode, and a standard surgical approach was employed. Once there was adequate exposure of the RW, the CI was seated under the temporalis muscle, and a sterile ultrasound drape with a telemetry magnet was placed over the skin to establish a connection with the device.

The Cochlear Research Platform (v1.2) was used to measure the ECochG response. A facial recess approach was used to place the ground electrode in the RW niche, and 100 repetitions of tone bursts at 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz were presented at ~100 dB SPL, alternating between rarefaction and condensation starting phases. The recording epoch was 18 ms with a sampling rate of 20.9 kHz for all frequencies, and the rise and fall times were 1 ms.

Signal Analysis

The ECochG responses were analyzed offline using custom MATLAB R2020a software (Mathworks Corp., Natlick, MA). The recorded responses to acoustic stimuli were plotted, and the ongoing portion of the response waveform was selected for FFT. Significant peaks were identified when the response magnitude exceeded the noise floor by 3 standard deviations (20,21,26). The noise floor was calculated using the variance and mean of 6 adjacent bins. The ECochG-total response (ECochG-TR) was computed as the sum of the significant peaks in each spectrum for the first 3 harmonics of the 4 stimulus frequencies (250–2000 Hz).

Speech Perception and Cognitive Measures

Participants underwent pre-implant audiometric evaluation using a modified Hughson-Westlake procedure. Speech perception was tested at candidacy, 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-activation with only the cochlear implant activated (CI-alone condition) using the CNC word test, traditionally administered in quiet conditions for word recognition, along with the AzBio sentences test, conducted in both quiet and in +10 dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions to assess comprehension capabilities in diverse auditory settings (27,28). When performing these tests, any additional hearing assistance (like hearing aids in the non-implanted ear or acoustic component of a hybrid CI) was turned off, and ipsilateral and contralateral ear canals were occluded, ensuring that the participant was relying solely on the CI for hearing. Cognition was assessed using the MoCA score, which is a cognitive screening measure (29).

Angular Insertion Depth (AID)

Postoperative computed tomography (CT) scans and 3D reconstructions were used to assess electrode position and cochlear anatomy post-surgery. The methodology used to quantify the AID and number of electrodes in each scala was previously described (30,31). Electrode position was determined by viewing the composite CT volume along the mid-modiolar axis, with the RW as the 0° reference point. The most apical electrode’s angular position was measured by rotation about the mid-modiolar axis from the 0° reference point.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to confirm normality of continuous level variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to determine relationships between ECochG-TR, demographic variables (age), audiologic variables (etiology of hearing loss, preoperative-speech perception testing, bilateral CIs, use of hybrid stimulation, duration of hearing loss), surgical variables (electrode type, AID) and speech perception outcomes (CNC scores, AzBio in quiet and noise). Simple and multiple linear regression analyses were performed to predict performance in quiet and noise using variables with p-values <0.05. A hierarchical model approach was used to evaluate the incremental role of audiologic performance and cognitive scores over ECochG-TR in predicting speech perception scores. Logistic regression was performed to identify predictors associated with poor performance, using dichotomized CNC scores (<40% and ≥40%). SPSS 27 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for all statistical analyses (α = 0.05, two-tailed).

RESULTS:

Tables 1–2 presents demographic and audiologic characteristics of 239 adult subjects who underwent intraoperative ECochG. Females comprised 38.9% of the study population, and the mean age at surgery was 62.6 years (SD = 23.4 years). Sensorineural hearing loss of unknown origin was the most common cause of hearing loss. A perimodiolar electrode array was implanted in the majority of patients (N = 195, 81.6%).

Table 1:

Demographic information of 239 patients who met the inclusion criteria and underwent cochlear implantation with 3-, 6-, or 12-month follow-up for round window electrocochleography recordings.

| Mean ± STD or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 62.6 ± 23.4 |

| Electrode Array Type | |

| Perimodiolar | 195 (81.6) |

| Lateral Wall | 44 (18.4) |

| Laterality | |

| Left | 117 (49.0) |

| Right | 122 (51.0) |

| Duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss (yrs) | 14.1 ± 18.4 |

| Etiology of hearing loss | |

| Unknown | 159 (66.5) |

| Meniere’s Disease | 13 (5.4) |

| Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss | 28 (11.7) |

| Infectious | 10 (4.2) |

| Congenital | 29 (12.1) |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Score | 25.3 ± 4.1 |

| Prior Contralateral Implant | |

| No | 200 (83.7) |

| Yes | 39 (16.3) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 148 (61.9) |

| Female | 91 (38.1) |

| Apical Electrode Insertion Angle (deg) | 376.3 ± 59.8 |

Table 2:

Speech-perception performance for all 239 subjects who underwent round window electrocochleography recordings at candidacy, 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-activation.

| AzBio in Quiet, preoperative | 17.8 ± 19.8 |

| AzBio in Noise (+10 dB signal-to-noise ratio), preoperative | 6.9 ± 10.0 |

| CNC, preoperative | 13.5 ± 14.6 |

| AzBio in Quiet, 3 months | 52.0 ± 28.9 |

| AzBio in Noise (+10 dB signal-to-noise ratio), 3 months | 24.2 ± 24.8 |

| CNC, 3 months | 41.9 ± 22.9 |

| AzBio in Quiet, 6 months | 60.4 ± 26.3 |

| AzBio in Noise (+10 dB signal-to-noise ratio), 6 months | 29.7 ± 24.9 |

| CNC, 6 months | 49.7 ± 21.9 |

| AzBio in Quiet, 12 months | 68.9 ± 25.3 |

| AzBio in Noise (+10 dB signal-to-noise ratio), 12 months | 36.0 ± 26.7 |

| CNC, 12 months | 54.0 ± 22.6 |

Electrocochleography-Total Response (ECochG-TR)

ECochG responses were observed in 98.7% (236/239) of subjects, with three exceptions whose responses were below the system’s noise floor (21.6 dB re:1 µV). Preoperative speech-perception scores (CNC or AzBio in quiet/noise) and age did not show a significant correlation with ECochG-TR (p > 0.05). Outliers included cases where perilymph was suctioned from the cochlea due to a traumatic RW approach or where the sound tube was crimped due to improper draping, as demonstrated by a rise in all responses after draping removal at the end of surgery.

Angular Insertion Depth (AID)

Factors such as array length, design, surgical approach, and individual cochlear morphology influenced the AID of the most apical contact, with AID ranging from 135.0° to 475.0° (median = 396.0°, IQR = 352.0° to 414.5°) for the entire cohort. Postoperative CT imaging showed complete insertion of the electrode array in 96.2% of subjects, and all insertions were performed within scala tympani.

Speech Perception in Quiet

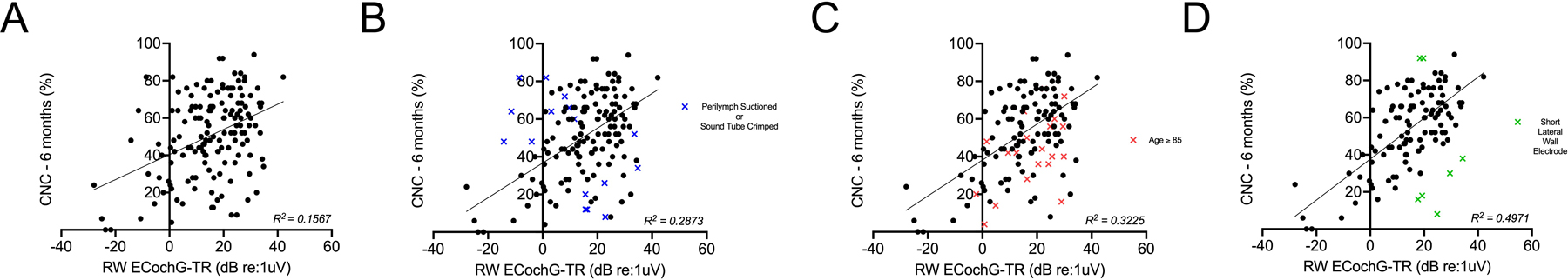

After 6 months of activation, CNC and AzBio scores in quiet were 49.7 ± 21.9% and 60.4 ± 26.3%, respectively. Weak correlations were observed between CNC and duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss (r = −0.19, p = 0.04) and AID (r = 0.29, p = 0.01), but not with other variables such as age, electrode type, etiology of hearing loss, preoperative speech-perception testing, MoCA score, bilateral CIs, or use of hybrid stimulation (p > 0.05). The weak correlations between duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss and speech-perception performance are shown comprehensively in Figure 1. ECochG-TR measured at the RW moderately correlated with CNC (r = 0.59, p < 0.0001). A multivariate model using MoCA, ECochG-TR, and MoCA*ECochG-TR interaction explained 47.8% of the variability in CNC at 6-months, while AID and duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss did not significantly improve the model. Removing subjects >85 years old and those with short lateral wall electrodes increased the model’s explanatory power to 49.7% (Figure 2). Additionally, we dichotomized CNC at 6-months into two cohorts – (1) CNC <40% and (2) CNC ≥40% – and found that similar demographic/audiologic variables (i.e., ECochG-TR, duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss, and MoCA score) were significant in this logistic regression model.

Figure 1:

Correlation between duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss and speech-perception performance, measured by AzBio sentences in quiet, AzBio sentences in noise at +10 dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and CNC words at 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-activation. Minimal correlation was observed between cochlear implant performance and duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss.

Figure 2:

Correlation between electrocochleography-total response (ECochG-TR) and speech-perception performance, as measured by CNC words at 6 months. (A) Weak-to-moderate correlation between round window ECochG-TR and CNC at 6 months was observed in all subjects who had speech-perception testing performed. (B) Subjects with a traumatic approach to the round window and perilymph suctioned prior to ECochG measurement, or where the sound tube was crimped, were excluded, resulting in a moderate correlation. (C) Subjects older than 85 were further excluded from (B), resulting in a moderate-to-strong correlation. (D) Removal of short lateral wall electrodes (CI624) from (C) resulted in an even stronger correlation between round window ECochG-TR and CNC at 6 months.

We also examined the association between ECochG-TR and CNC scores at 3-months and 12-months post-activation. ECochG-TR accounted for 42.6% and 20.8% of the variability in CNC scores at 3 and 12-months, respectively. We observed similar relationships with AzBio in quiet: 41.0%, 42.4%, and 8.4% of the variability in performance at 3, 6, and 12-months. Interestingly, there was no significant correlation between ECochG-TR and the magnitude of the change in CNC words from candidacy to 6-months post-activation. Table 3 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between ECochG-TR, various demographic, audiologic, and surgical variables, and CI speech-perception performance at 3-, 6-, and 12-months.

Table 3:

Pearson correlations (r) with 95% confidence intervals of demographic, audiologic, and surgical factors with postoperative speech-perception performance in quiet and noise. Bolded values were those that were statistically significant with p-values <0.05.

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNC | AzBio in Quiet | AzBio in Noise | CNC | AzBio in Quiet | AzBio in Noise | CNC | AzBio in Quiet | AzBio in Noise | |

| Age | −0.22 (−0.36 to −0.07) | −0.28 (−0.42 to −0.12) | −0.36 (−0.50 to −0.21) | −0.12 (−0.29 to 0.05) | −0.12 (−0.30 to 0.06) | −0.36 (−0.49 to −0.15) | −0.14 (−0.31 to 0.04) | −0.28 (−0.46 to −0.09) | −0.47 (−0.63 to −0.28) |

| Angular Insertion Depth | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.42) | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.41) | 0.19 (0.00 to 0.38) | 0.26 (0.07 to 0.43) | 0.23 (0.03 to 0.41) | 0.21 (−0.01 to 0.41) | 0.25 (0.05 to 0.43) | 0.17 (−0.03 to 0.37) | 0.23 (−0.01 to 0.45) |

| ECochG-TR | 0.65 (0.43 to 0.86) | 0.64 (0.41 to 0.85) | 0.39 (0.24 to 0.61) | 0.71 (0.49 to 0.87) | 0.65 (0.41 to 0.84) | 0.42 (0.29 to 0.56) | 0.46 (0.32 to 0.59) | 0.29 (0.12 to 0.39) | 0.34 (0.19 to 0.54) |

| Duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss | −0.10 (−0.24 to 0.04) | −0.09 (−0.23 to 0.06) | −0.10 (−0.25 to 0.05) | −0.12 (−0.27 to 0.03) | −0.14 (−0.29 to 0.02) | −0.13 (−0.30 to 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.20 to 0.14) | −0.01 (−0.19 to 0.17) | 0.00 (−0.20 to 0.20) |

| MoCA Score | 0.17 (0.02 to 0.31) | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.41) | 0.37 (0.22 to 0.50) | 0.11 (−0.05 to 0.26) | 0.17 (0.01 to 0.33) | 0.38 (0.18 to 0.49) | 0.20 (0.02 to 0.36) | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.41) | 0.41 (0.22 to 0.56) |

Speech Perception in Noise

At 6-months post-activation, AzBio +10 dB SNR mean score was 29.8 ± 24.3%. AzBio in quiet and AzBio +10 dB SNR were strongly correlated (r = 0.82, p < 0.0001; Figure 3A). ECochG-TR had only a weak linear correlation with AzBio +10 dB SNR (r = 0.42, p < 0.0001; Figure 3B). To explore potential predictors of AzBio +10 dB SNR at 6-months, we performed univariate linear regression analyses for various quantitative predictive variables, including MoCA, age, duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss, and angular insertion depth. MoCA and age weakly-to-moderately correlated with AzBio +10 dB SNR at 6-months (r = 0.38, p < 0.0001; r = −0.36, p < 0.0001, respectively).

Figure 3:

Understanding the variability in speech-perception performance in noise (as measured by AzBio +10 dB signal-to-noise ratio [SNR]). While good performance in quiet is necessary, it is not sufficient for good performance in noise. Additionally, various factors such as cognitive ability and the electrical response of the cochlea can affect speech-perception performance with a cochlear implant in noisy environments. (A) A strong linear correlation exists between performance in quiet and performance in noise, as measured by the AzBio test. While good performance in quiet (AzBio in Quiet) is necessary for good performance in noise (AzBio in Noise), it is not sufficient. There is significant variability in noise performance, even in patients who perform well in quiet with a cochlear implant in the CI-only condition. (B) Electrocochleography-total response (ECochG-TR) is a weak predictor of performance in noise (AzBio + 10 dB SNR). (C) Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores show a moderate linear correlation with performance in noise, (D) By using multivariate modeling with ECochG-TR, MoCA, and the interaction term of MoCA*ECochG-TR, it is possible to predict 36.8% of the variability in cochlear implant performance in noise after six months.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis showed that ECochG-TR had a significant correlation with AzBio +10 dB SNR and incorporating MoCA score substantially improved the variance explained (R2 = 0.34, p < 0.0001). Adding the two-way interaction of ECochG-TR and MoCA further improved the model (R2 = 0.45, p < 0.0001; Table 4). Other variables, including AID, duration of severe-to-profound hearing loss, type of electrode array, etiology of hearing loss, electroacoustic stimulation, and bilateral CIs, did not significantly improve the model. Similar models for AzBio +10 dB SNR at 3- and 12-months explained 34.2% and 33.8% of the variability, respectively. Age had a significant linear correlation with AzBio +10 dB SNR at 6-months, but it was not a significant predictor due to collinearity with MoCA (r = 0.59, p < 0.0001).

Table 4:

Multivariate regression model for prediction of performance in noise (AzBio +10 dB SNR) at 6 months. Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) score, electrocochleography-total response (ECochG-TR), and their interaction explained 45% of the variability in AzBio +10 dB SNR at 6 months (Model 3).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | β | β |

| Constant | 17.28 | −46.26** | −11.33 |

| ECochG-TR | 0.77** | 0.76** | −1.40* |

| MoCA | -- | 2.57** | 1.18* |

| ECochG-TR*MoCA | -- | -- | 0.09* |

| R 2 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.45 |

| ΔR 2 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

ΔR2 represents the variation in the dependent variable explained by the specific independent variable. β = standardized regression coefficient

p = < 0.05

p = < 0.001.

DISCUSSION:

The variability in CI performance has been a source of frustration for both researchers and clinicians, as it is difficult to predict whether a patient will have poor or excellent performance after implantation. Recent studies show that ECochG can provide a detailed understanding of the auditory periphery, improving predictability of CI performance (20–22). ECochG-TR, the sum of spectral magnitudes of the ongoing response, has a strong association with speech perception performance in quiet for adult CI users. The current study aimed to confirm the importance of cognition (as measured by MoCA) in predicting performance in noise and validate previous models for predicting performance in quiet using ECochG-TR, AID, and other traditional biographic and audiological variables using the largest sample size to date. The model, including ECochG-TR, MoCA, and the interaction term MoCA*ECochG-TR, accounted for 45.1% of the variance in AzBio in noise at 6-months post-activation.

ECochG-TR and Audiologic/Demographic Variables

ECochG recordings provide information about hair cell and neural function in different structures of the cochlea. The cochlear microphonic (32) (CM) and summating potential (33) (SP) reflect hair cell function, while the compound action potential (CAP) reflects synchronous action potential across multiple fibers, and the auditory nerve neurophonic (34) (ANN) represents the phase-locked neural firing during a tone’s duration.

ECochG-TR serves as a reliable proxy for cochlear health as it provides information about both hair cell and auditory nerve function. While previous studies have found only moderate correlations between unaided hearing detection thresholds and the ECochG response, there are cases where patients with poor audiogram thresholds have large ECochG-TR and perform well with a CI (24). This finding supports the idea of cochlear synaptopathy, where hair cells are present but there is a loss of synapses between hair cells and auditory nerve fibers, leading to a discrepancy between audiogram thresholds and ECochG-TR. We hypothesize that the responsive hair cells are supporting viable spiral ganglion cells although the functional synapses are lacking. In this study, we also found that ECochG-TR did not correlate significantly with preoperative speech-perception scores or age, emphasizing its unique contribution as a measure of cochlear health that cannot be evaluated through other variables.

Predicting Speech-Perception Performance in Quiet

Previous studies consistently show ECochG-TR as a strong predictor of CI performance in quiet, accounting for up to 50% of the variability in CNC at 3- or 6-months post-activation (20,21,23,24,26). In our study, which analyzed the largest sample size to date (N=239), we found a significant positive correlation between ECochG-TR and CNC performance in the CI-only condition at 6-months post-activation, explaining 28.7% of the variability. After removing subjects above 85 yrs of age, ECochG-TR’s explanatory power increased to 32.2%, consistent with previous research (22). Prior studies have suggested that the delay or decline in performance for older subjects may be related to central rather than peripheral factors (35–37). The model’s accuracy improved when we removed the short lateral wall electrodes, highlighting the importance of preserving hearing for shallow insertions. We next generated a multivariate model using ECochG-TR, MoCA, and MoCA*ECochG-TR, which explained 47.8% of CNC variability at 6-months post-activation. These results highlight the essential role of ECochG-TR in predicting CI performance in quiet.

To compare the impact of AID on speech-perception performance, we contrasted our findings with Canfarotta et. al.’s study (25). Their results showed that the interaction between AID and array design, along with ECochG-TR, accounted for 72% of the variance in speech perception outcomes in quiet. In contrast, we did not observe a similar impact of AID in our study. Differences in methods, such as our use of postoperative CT imaging and 3-D reconstruction to measure the angular insertion depth of the most apical electrode compared to Canfarotta et. al.’s use of intraoperative X-ray to estimate insertion depth, may have influenced the predictive role of AID on speech-perception outcomes. Our study also evaluated two electrode types with similar lengths, while Canfarotta et. al. used a range of electrodes with varying lengths and configurations related to modiolar proximity, which could have contributed to the discrepancy.

Previous ECochG-TR studies have focused on predicting postoperative CI performance rather than investigating pre- to postoperative changes. Our study found no significant correlation between ECochG-TR and the change in CNC scores at 6-months post-activation (ΔCNC), underscoring the utility of ECochG-TR as an indicator of potential cochlear health, and therefore, as a predictor of postoperative speech perception, regardless of preoperative performance levels.

We also analyzed the association between ECochG-TR and speech perception outcomes at 3- and 12-months post-activation. ECochG-TR can account for up to 42.6% and 20.8% of the variance in CNC scores at 3- and 12-months, respectively, and explained 41.0%, 42.4%, and 8.4% of the variance in AzBio scores at 3-, 6-, and 12-months. While ECochG-TR explained a similar proportion of variance for both AzBio in quiet and CNC at 3- and 6-months, it explained a smaller proportion of CI performance at 12-months. A possible explanation for the diminishing correlation for long-term CI performance is that the well-known frequency-to-place mismatch between the native tonotopic map and the frequency allocation of the CI electrodes requires the recipient to undergo adaptation (which may take longer than 6-months) in order to recognize the degraded signal (38–40). We hypothesize that the 6-month mark may yield the most significant results due to the combination of auditory adaptation to the new electrical stimulation from the CI (41) and the intensive aural rehabilitation typically undergone during this period (42), both contributing to a sharp increase in performance.

Our study confirms ECochG-TR as a superior predictor of CI performance in quiet, surpassing traditional demographic and audiologic variables. Even when combined with these variables in a multivariate model, ECochG-TR retained its dominant predictive power. Duration of hearing loss and severe-to-profound hearing loss did not correlate with CI performance, challenging the conventional belief that prolonged deafness results in poor speech recognition after cochlear implantation.

Predicting Speech-Perception Performance in Noise

Previous research has primarily focused on predicting CI performance in quiet environments, but measuring performance in noisy environments is more practical and similar to daily functioning. In a previous study (24), we found that ECochG-TR, cognition (measured by MoCA), and their interaction accounted for almost 60% of the variability in performance in noise. However, the study had a significant limitation: all ECochG-TR data were collected postoperatively at 3-months, which limits its utility as a preoperative predictive tool. This study aims to investigate the relationship between RW ECochG-TR and performance in noise.

We initially found a strong correlation between performance in quiet and noise conditions, with AzBio in quiet accounting for 67.2% of the variance in AzBio in noise. While postoperative performance in quiet cannot be used to predict postoperative performance in noise, our findings indicate that good performance in quiet is a strong predictor but not a guarantee for good performance in noisy environments.

Our study found that ECochG-TR and MoCA were the most significant predictors of CI performance in noise, surpassing other demographic and audiological variables. While large ECochG-TR values were consistently associated with good performance in quiet, they were not not always indicative of good performance in noise. Although MoCA scores explained only 15% of the variability in AzBio in noise at 6 months, they remained an important factor for good performance in noise. A high MoCA score alone or a large ECochG-TR value alone was insufficient to compensate for poor cognitive function or cochlear health, respectively.

Similar to our previous study (24), we next developed a multivariate model using MoCA, ECochG-TR, and the interaction term MoCA*ECochG-TR, explaining 45.1% of the variability in CI performance in noise. A normal MoCA score (≥26) and large ECochG-TR value are necessary for excellent performance in noise. Age had a weak correlation that did not improve multivariate model accuracy due to collinearity with MoCA. Age’s impact on cognition and performance in noise is likely already captured in the MoCA score. However, it is worth noting that while MoCA provides a general overview of cognitive function, it may not fully capture the cognitive capacities that specifically influence CI performance. Given the significance of cognitive function in CI outcomes, research is ongoing to explore more comprehensive and focused cognitive assessments, incorporating measures of auditory working memory and attention, to better explain the observed variability.

Future Directions

CI performance is dependent on a good cochlear-neural and central auditory substrate as well as a properly functioning device and appropriate surgical placement. The present study provides valuable insights into the relationship between ECochG-TR, cognition, and speech perception in CI recipients suggesting these are good biomarkers of cochlear and central auditory substrates. However, in our study, the lack of preoperative ECochG-TR measurements hinders its use prior to surgery. While the data is rich in indicating a correlation with postoperative speech perception, its availability before the procedure could provide a more thorough evaluation and better inform patient counseling. Despite this limitation, our study emphasizes the need for developing preoperative predictive tools to optimize CI outcomes. One promising approach is using a transtympanic method with electrode placement on the promontory. Notably, intraoperative promontory ECochG-TR, while similar in response pattern, tends to have a smaller amplitude compared to RW ECochG-TR due to the increased distance from the source of the cochlear microphonic. Nevertheless, this measure correlates well with RW ECochG-TR and performance in quiet conditions (23), suggesting the potential for transtympanic promontory ECochG-TR to predict performance in quiet. The availability of a reliable preoperative technique for measuring ECochG-TR could lead to better outcomes for individual patients by facilitating tailored surgical and rehabilitation strategies.

CONCLUSIONS:

This study advances our understanding of the relationship between ECochG-TR, cochlear health, and CI performance. Our findings highlight the critical role of the cochlear neural substrate in driving speech perception performance, particularly in noisy environments. Good residual cochlear function, as measured by ECochG-TR, is necessary for performance in quiet, but optimal performance in noise requires both healthy cochlear function (ECochG-TR) and intact cognitive function (MoCA). Demographic, audiologic, and surgical variables have weak correlations with CI performance, emphasizing the need for improved preoperative predictive tools to better inform patient counseling and optimize outcomes. The development of a reliable preoperative technique for measuring ECochG-TR, such as a transtympanic approach, would enable tailored surgical and rehabilitation approaches, leading to better outcomes for individual patients.

Acknowledgements:

Cochlear Corp provided equipment to measure real-time electrocochleography responses.

Source of Funding:

AW – supported by the American Neurotology Society research grant and NIH/NIDCD institutional training grant T32DC000022

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

MAS – Cochlear Ltd.; CCW – consultant for Stryker and Cochlear Ltd.; ND – None; JAH – Consultant for Cochlear Ltd; CAB – consultant for Advanced Bionics, Cochlear Ltd., Envoy, and IotaMotion, and has equity interest in Advanced Cochlear Diagnostics, LLC

This article will be presented at the 2023 57th Annual American Neurotology Society (ANS) Spring Meeting; Boston, Massachusetts; May 7th, 2023.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Eshraghi AA, Nazarian R, Telischi FFet al. The Cochlear Implant: Historical Aspects and Future Prospects. The Anatomical Record 2012;295:1967–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchman CA, Gifford RH, Haynes DSet al. Unilateral Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;146:942–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchman CA, Herzog JA, McJunkin JLet al. Assessment of Speech Understanding After Cochlear Implantation in Adult Hearing Aid Users: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2020;146:916–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubinstein JT, Parkinson WS, Tyler RSet al. Residual Speech Recognition and Cochlear Implant Performance: Effects of Implantation Criteria. Otology & Neurotology 1999;20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gantz BJ, Woodworth GG, Knutson JFet al. Multivariate predictors of audiological success with multichannel cochlear implants. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology 1993;102:909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boisvert I, Reis M, Au Aet al. Cochlear implantation outcomes in adults: A scoping review. PloS one 2020;15:e0232421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Harris MSet al. Three challenges for future research on cochlear implants. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 2017;3:240–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blamey P, Arndt P, Bergeron Fet al. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants. Audiology & neuro-otology 1996;1:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blamey P, Artieres F, Başkent Det al. Factors Affecting Auditory Performance of Postlinguistically Deaf Adults Using Cochlear Implants: An Update with 2251 Patients. Audiology and Neurotology 2013;18:36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holden LK, Finley CC, Firszt JBet al. Factors affecting open-set word recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Ear and hearing 2013;34:342–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazard DS, Vincent C, Venail Fet al. Pre-, per- and postoperative factors affecting performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: a new conceptual model over time. PloS one 2012;7:e48739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao EE, Dornhoffer JR, Loftus Cet al. Association of Patient-Related Factors With Adult Cochlear Implant Speech Recognition Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery 2020;146:613–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finley CC, Holden TA, Holden LKet al. Role of electrode placement as a contributor to variability in cochlear implant outcomes. Otol Neurotol 2008;29:920–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goudey B, Plant K, Kiral Iet al. A MultiCenter Analysis of Factors Associated with Hearing Outcome for 2,735 Adults with Cochlear Implants. Trends in Hearing 2021;25:23312165211037525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis MH, Johnsrude IS. Hearing speech sounds: top-down influences on the interface between audition and speech perception. Hearing research 2007;229:132–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenfelt S, Rönnberg J. The signal-cognition interface: interactions between degraded auditory signals and cognitive processes. Scandinavian journal of psychology 2009;50:385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattys SL, Davis MH, Bradlow ARet al. Speech recognition in adverse conditions: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes 2012;27:953–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Başkent D, Clarke J, Pals Cet al. Cognitive Compensation of Speech Perception With Hearing Impairment, Cochlear Implants, and Aging: How and to What Degree Can It Be Achieved? Trends in Hearing 2016;20:2331216516670279. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moberly AC, Bates C, Harris MSet al. The Enigma of Poor Performance by Adults With Cochlear Implants. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2016;37:1522–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzpatrick DC, Campbell AP, Choudhury Bet al. Round window electrocochleography just before cochlear implantation: relationship to word recognition outcomes in adults. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2014;35:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClellan JH, Formeister EJ, Merwin WH, 3rdet al. Round window electrocochleography and speech perception outcomes in adult cochlear implant subjects: comparison with audiometric and biographical information. Otol Neurotol 2014;35:e245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontenot TE, Giardina CK, Dillon Met al. Residual Cochlear Function in Adults and Children Receiving Cochlear Implants: Correlations With Speech Perception Outcomes. Ear and hearing 2019;40:577–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walia A, Shew MA, Lee DSet al. Promontory Electrocochleography Recordings to Predict Speech-Perception Performance in Cochlear Implant Recipients. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2022;43:915–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walia A, Shew MA, Kallogjeri Det al. Electrocochleography and cognition are important predictors of speech perception outcomes in noise for cochlear implant recipients. Scientific Reports 2022;12:3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canfarotta MW, O’Connell BP, Giardina CKet al. Relationship Between Electrocochleography, Angular Insertion Depth, and Cochlear Implant Speech Perception Outcomes. Ear Hear 2021;42:941–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fontenot TE, Giardina CK, Dillon MTet al. Residual Cochlear Function in Adults and Children Receiving Cochlear Implants: Correlations With Speech Perception Outcomes. Ear and Hearing 2019;40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson GE, Lehiste I. Revised CNC lists for auditory tests. J Speech Hear Disord 1962;27:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spahr AJ, Dorman MF, Litvak LMet al. Development and validation of the AzBio sentence lists. Ear Hear 2012;33:112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian Vet al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skinner MW, Holden TA, Whiting BRet al. In vivo estimates of the position of advanced bionics electrode arrays in the human cochlea. The Annals of otology, rhinology & laryngology. Supplement 2007;197:2–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teymouri J, Hullar TE, Holden TAet al. Verification of computed tomographic estimates of cochlear implant array position: a micro-CT and histologic analysis. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2011;32:980–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patuzzi RB, Yates GK, Johnstone BM. The origin of the low-frequency microphonic in the first cochlear turn of guinea-pig. Hearing research 1989;39:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durrant JD, Wang J, Ding DLet al. Are inner or outer hair cells the source of summating potentials recorded from the round window? The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1998;104:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhury B, Fitzpatrick DC, Buchman CAet al. Intraoperative round window recordings to acoustic stimuli from cochlear implant patients. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2012;33:1507–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dillon MT, Buss E, Adunka MCet al. Long-term Speech Perception in Elderly Cochlear Implant Users. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2013;139:279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts DS, Lin HW, Herrmann BSet al. Differential cochlear implant outcomes in older adults. Laryngoscope 2013;123:1952–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedland DR, Runge-Samuelson C, Baig Het al. Case-control analysis of cochlear implant performance in elderly patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;136:432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svirsky MA, Talavage TM, Sinha Set al. Gradual adaptation to auditory frequency mismatch. Hear Res 2015;322:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walia A, Ortmann AJ, Lefler Set al. Direct in vivo measurement of cochlear place coding in humans. medRxiv 2023:2023.04.13.23288518. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters JPM, Bennink E, van Zanten GA. Comparison of Place-versus-Pitch Mismatch between a Perimodiolar and Lateral Wall Cochlear Implant Electrode Array in Patients with Single-Sided Deafness and a Cochlear Implant. Audiology and Neurotology 2019;24:38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mario A Svirsky ASHSHNTTLPMS. Auditory Learning and Adaptation after Cochlear Implantation: A Preliminary Study of Discrimination and Labeling of Vowel Sounds by Cochlear Implant Users. Acta oto-laryngologica 2001;121:262–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu Q-J, Nogaki G, Galvin JJ. Auditory Training with Spectrally Shifted Speech: Implications for Cochlear Implant Patient Auditory Rehabilitation. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2005;6:180–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]