Abstract

Purpose:

Nearly all older patients receiving post-acute home health care (HHC) use potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) that carry a risk of harm. Deprescribing can reduce and optimize the use of PIMs, yet it is often not conducted among HHC patients. The objective of this study was to gather perspectives from patient, provider and HHC clinician stakeholders on tasks that are essential to post-acute deprescribing in HHC.

Methods:

A total of 44 stakeholders, including 14 HHC patients, 15 providers (including nine primary care physicians (PCP), four pharmacists, one hospitalist, and one nurse practitioner), and 15 HHC nurses participated. The stakeholders were from 12 U.S. states, including New York (29), Colorado (2), Connecticut (1), Illinois (2), Kansas (2), Massachusetts (1), Minnesota (1), Mississippi (1), Nebraska (1), Ohio (1), Tennessee (1), and Texas (2). First, individual interviews were conducted by experienced research staff via video conference or telephone. Next, the study team reviewed all interview transcripts and selected interview statements regarding stakeholders’ suggestions for important tasks needed for post-acute deprescribing in HHC. Afterward, concept mapping was conducted in which stakeholders sorted and rated selected interview statements regarding ‘importance’ and ‘feasibility’. Content analysis was conducted of data collected in the individual interviews and mixed method analysis was conducted of data collected in the concept mapping.

Findings:

Four essential tasks were identified for post-acute deprescribing in HHC: 1) ongoing review and assessment of medication use; 2) patent-centered and individualized plan of deprescribing; 3) timely and efficient communication among members of the care team; and 4) continuous and tailored medication education to meet patient needs. Among these tasks, developing patient-centered deprescribing considerations was considered the most important and feasible, followed by medication education, review and assessment of medication use, and communication.

Implications:

Deprescribing during the transition of care from hospital to home requires the following: continuous medication education for patients, families and caregivers; ongoing review and assessment of medication use; patient-centered deprescribing considerations; and effective communication and collaboration among the PCP, HHC nurse, and pharmacist.

Keywords: Home Health Care, Polypharmacy, Deprescribing, Qualitative Research, Transitions of Care, Patient-Centered Care

INTRODUCTION

Medications that could be harmful given changes in the patient’s health status and treatment objectives are known as potentially inappropriate medication (PIM).1,2 Prior studies using various methodologies of identifying of PIMs of different medication classes have shown that from 20% to 98% of older adults receiving home health care (HHC) services use at least one PIM.3–9 PIM use can lead to multiple negative consequences, including adverse reactions from medications,10,11 interactions between medications, deterioration of geriatric syndromes such as delirium, falls, and depression,12 and an elevated risk for hospitalization,3,13–16 and mortality.17

Deprescribing - the systematic process of discontinuing or reducing the use of unnecessary and potentially harmful medications - is an effective way to reduce PIM use.18–22 Deprescribing can lower drug costs and burden,23 and improve medication adherence by reducing pill burden.22 Further, deprescribing may benefit patients’ cognitive and physical functioning,24,25 and quality of life,25,26 and reduce their risk for falls,25,27 hospitalizations22,25,26,28,29, and death,25,26,29,30 though existing evidence is not conclusive.29,31

The period during which patients receive HHC provides an opportunity for post-acute deprescribing for several reasons. First, prescription modifications are often made both during hospitalization32,33 and after discharge,34 which can cause confusion among patients and increase the risk of medication discrepancies and/or errors.35 Medication review and reconciliation after hospital discharge is essential, therefore, to ensure patient safety and positive health outcomes. Second, the vast majority of older persons with multiple chronic conditions who live in the community return home following acute and post-acute care with support of HHC agencies.36,37 Nonetheless, deprescribing in post-acute HHC patients is often not implemented.38

In this study, we conducted individual qualitative interviews and group-based concept mapping with key stakeholders to learn their perceptions of post-acute deprescribing for older patients in HHC. We especially explored the key tasks necessary to implement and/or improve post-acute deprescribing in HHC, and the priority (i.e., feasibility and importance) of these tasks to inform the development of a deprescribing intervention in HHC.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Study Design

The study consisted of individual qualitative interviews and group-based concept mapping to augment the translation and implementation potential of findings.39 Concept mapping was based on the data from individual qualitative interviews. We chose this approach because it 1) collects information about group-level perceptions of tasks that are essential to deprescribing, and 2) allows participants to prioritize the tasks (i.e., feasibility and importance), which can inform the development of a deprescribing intervention in HHC. The University of Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB #00006218).

Sample

We used purposeful sampling and recruited stakeholders involved in the process of deprescribing during the hospital-to-home transition. The stakeholders included 1) recently hospitalized older patients who received HHC services after hospital discharge; 2) providers including pharmacists and prescribers in the continuum of acute, post-acute and primary care including primary care physicians (PCPs), hospitalists, and a nurse practitioner who works at post-acute skilled nursing facilities; and 3) registered nurses and clinical care directors in HHC.

Eligibility criteria for all stakeholder groups included: the ability to self-consent and English-speaking; without uncorrected difficulties in hearing, vision, and verbal expression that limit their ability to communicate effectively during interviews. Additional eligibility criteria for patients included: a) ≥65 years of age; b) hospitalized and discharged home with HHC services in the previous 24 months; c) taking ≥5 prescription medications regularly; and d) not receiving hospice care. Eligibility criteria for clinicians included: clinical practice in hospital medicine, primary care, post-acute care, or pharmacy for >12 months, or working at an HHC agency as a registered nurse or a patient care director for >12 months.

Recruitment

The patients and providers were recruited locally from New York State. Using the approved list of HHC patients who previously provided their approval to be contacted about research studies, we conducted ongoing sorts of patient information by variables, if provided, such as race, ethnicity, and zip codes that we researched to be of low socioeconomic status in the upstate New York region. We focused our outreach on patients who were from under-represented racial/ethnic backgrounds and zip codes with low socioeconomic status.

Due to the large geographic variability in HHC availability and service utilization,40,41 we recruited HHC nurses from 12 states, including New York (2), Colorado (2), Connecticut (1), Illinois (2), Kansas (2), Massachusetts (1), Minnesota (1), Mississippi (1), Nebraska (1), Ohio (1), Tennessee (1), and Texas (1). Recruitment of providers and HHC nurses was dependent on their reaching out to the research team by phone or email (based on information on our study website and the newsletter distributed to members of the National Association of Home and Hospice Care), and no prioritization was applied in these participants’ enrollment based on their demographic status.

This study included a total of 44 participants consisting of 14 patients (all from New York state), 15 providers including 1 hospitalist, 1 nurse practitioner, 9 PCPs and 4 pharmacists (all from New York state), and 15 HHC nurses and clinical care directors (hereafter referred to as “HHC nurses”; from 12 U.S. states as described above). Among the participants, 19 participated in both interviews and concept mapping, 11 only participated in the individual interviews, and 14 only participated in the concept mapping.

Data Collection & Analysis

Individual Qualitative Interview

Data Collection:

Interviews were conducted using interview guides developed for each group of stakeholders (Appendices 1–3). These interview guides were grounded in the multidisciplinary deprescribing process with flexibility to explore novel ideas.25 We sought to understand stakeholders’ perspectives about their experience, processes, roles, training, workflow and challenges of deprescribing during hospital-to-home transitions. Trained research staff conducted individual telephone or video-conference interviews with each participant that lasted 60–90 minutes. Interviews were audiotaped and de-identified during transcription. Individual interviews in each stakeholder group continued until no new findings emerged specific to each of the three groups.

Data Analysis:

Qualitative data from audiotaped interviews and field notes were transcribed verbatim, reviewed and verified for accuracy, and entered into Atlas.ti for data management. We used a phased, iterative data analysis approach.42 Phase 1: We used open coding to identify and label novel ideas in the text, often using the participants’ own language. We then coded for pre-specified key concepts identified in prior studies as essential to multidisciplinary patient-centered deprescribing.18,43–46 Subsequently, we developed a coding scheme reflecting both novel findings and findings related to pre-specified concepts. Phase 2: We coded all transcripts using the coding scheme. Phase 3: We compared data across the three stakeholder groups to examine pattern variation in deprescribing tasks among older adults during post-acute care transitions to HHC.47–49 Statements about deprescribing tasks from the qualitative interviews were then used to develop statements for the concept mapping activity.

Credibility and trustworthiness:

Several strategies were used to strengthen the credibility and trustworthiness of our findings.50 First, research team meetings were held prior to data collection procedures to address subjective bias in the data collection tools. Three independent researchers coded all transcripts and reached consensus on the codes. Researchers maintained an audit trail of study materials, to include a decision log, debriefing notes and discussion notes. Regular meetings also were held among the interdisciplinary research team to assess the adequacy and comprehensiveness of analytical results.

Group Concept mapping

Data Collection:

Data for concept mapping were collected in three steps. First, we developed a focused prompt. With a goal of using findings from the concept mapping to guide the design of a deprescribing intervention for HHC, we developed the focus prompt, “A program to support medication optimization, including stopping or reducing unnecessary medications, for older patients after hospital discharge should include…”. We reviewed the transcripts of qualitative interviews and selected statements from those interviews that would serve as a response to the focus prompt. A total of 82 statements were chosen by the research team and used in the concept mapping activity.

Credibility and trustworthiness:

Three research team members individually selected statements from the interviews and compared their selections; consensus was reached among the final set of 82 selected interview statements used for further activities and analysis in concept mapping.

Concept mapping was conducted by participants primarily online (30/32) with two patients completing the activity by phone with research staff as they had no Internet access. We invited each participant to sort the 82 statements into piles based on their own interpretation of the similarity among statements and then label each pile with a name they thought best described the topic in each separate statement group. Then, using a Likert scale (1–5 ratings), they rated each statement on its feasibility (‘1’ [unfeasible] to ‘5’ [very feasible]) and importance to deprescribing (‘1’ [unimportant] to ‘5’ [extremely important]).

Data Analysis:

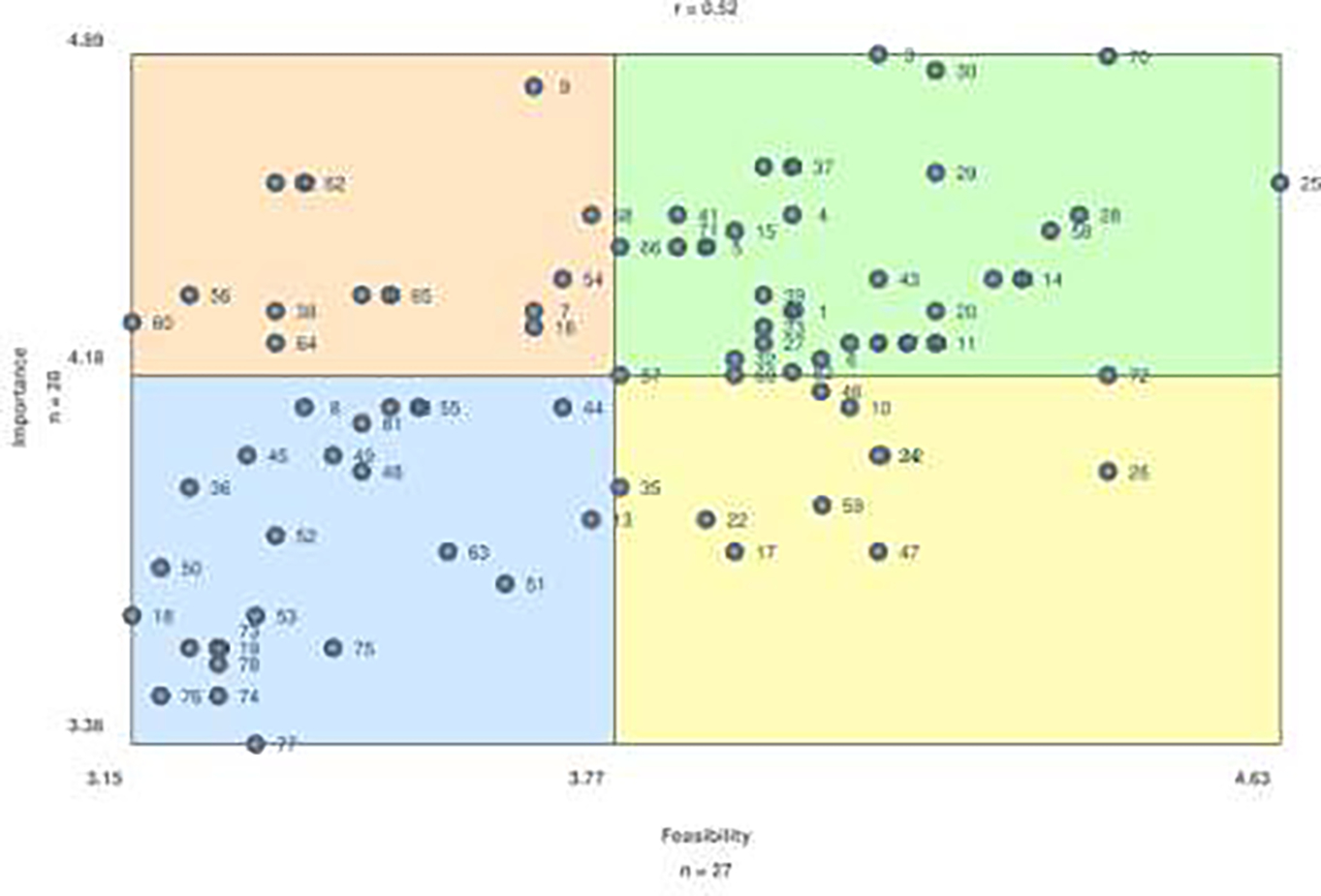

Concept mapping data were entered into a software program (groupwisdom™)39 for hierarchical cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling. The average feasibility and importance ratings of each statement across all participants were plotted, where statements with higher-than-average ratings of both feasibility and importance are in the GO-Zone (Fig 1. green) and statements with lower-than-average ratings of both feasibility and importance are in the NO-GO-Zone (Fig 1. blue).

Figure 1:

Feasibility and Importance Ratings of Selected Interview Statements (GO-Zone)

RESULTS

We collected data from 44 stakeholders, including 14 patients (average age 71.3 ± 5.06), 15 HHC nurses (average age 49.7 ± 12.08), and 15 clinicians (average age 41.9 ± 11.93), including nine PCPs, one hospitalist, four pharmacists, and one nurse practitioner. The stakeholders were mostly non-Hispanic white (88.6%) and female (70.5%). A breakdown of demographics of each stakeholder panel was provided in Appendix 1. In terms of work experience of the professionals, physicians, pharmacists and nurse practitioners had an average of 12.7 years (S.D.=11.68) serving in their current roles, and HHC nurses had an average of 11.0 (S.D.=11.28) years of experience in HHC.

The GO-Zone of feasibility and importance ranking of the statements regarding deprescribing tasks is shown in Figure 1. Statements in the high-importance & high feasibility and high-importance & low feasibility zones belong to four major categories: 1) assessment and review of medication use; 2) patient-centered, individualized plan of deprescribing recommendations; 3) timely and efficient communication among members of the care team; and 4) continued and tailored medication education to meet patient needs (Table 1). We did not focus on statements categorized with low importance, regardless of the feasibility ratings, as they were perceived to be of relatively less value to post-acute deprescribing than others according to the stakeholders.

Table 1.

Selected Interview Statements in the upper right quadrant of GO-Zone (most feasible and important)

| Category | Selected Interview Statements in Green ZONE | # |

|---|---|---|

| Medication review/assess | An accurate, complete, and updated list of all the medications a patient is taking including prescriptions, over the counter medications, and supplements. | 3 |

| Home-based assessment of the patient’s medication adherence, symptom changes, and potential medication side effects and interactions. | 5 | |

| Home health care nurses conducting regular medication reviews. | 6 | |

| Having home health care nurses as the “eyes and ears” in the patient’s home. | 27 | |

| HHC nurses assessing if the patient has any language barrier when communicating with the patient and caregiver. | 33 | |

| Primary care providers assessing if the patient has any language barrier when communicating with the patient and caregiver. | 34 | |

| HHC nurses assessing the patient’s ability to take medicines correctly including health literacy, mental status, vision, manual dexterity, and nutrition. | 37 | |

| Continuous monitoring of medication effects and related symptom changes to ensure safety of deprescribing. | 66 | |

| Tools to automatically identify and flag patients with high risk of adverse events related to medication use such as falls, nausea, and dizziness. | 69 | |

| Patient-centered deprescribing considerations | Home health care nurses building trust, rapport, and relationship with the patient. | 28 |

| Primary care providers building trust, rapport, and relationship with the patient. | 29 | |

| HHC nurses listening to the patient and understanding the patient’s perspectives and experiences with medications. | 43 | |

| Allowing the patient to have a voice in the discussion about medication use and changes. | 58 | |

| Doing what is the best for patient. | 70 | |

| Communication | Home health care nurses letting the primary care provider(s) know if there are issues related to medications such as patients not taking medications correctly or having concerns. | 30 |

| A better-defined role of HHC nurses in initiating proactive communication with primary care provider(s) for patients taking too many medications. | 32 | |

| Options for patients to choose the best method to communicate with clinicians about medications. | 57 | |

| HHC nurses calling the patient’s primary care provider(s) about urgent medication problems while at the patient’s home. | 61 | |

| Having clear roles on who responds to the patient’s requests. | 71 | |

| Education |

Understanding how a reduction of medication impacts the underlying medical condition and side effects. | 1 |

| Understanding how a reduction of medication impacts patients’ experiences and alignment with patients’ goals of care. | 2 | |

| A rationale and an understanding for why each medication is prescribed and indicated. | 4 | |

| Directly asking patients what they are taking or not taking and the reason for taking/not taking each medication. | 11 | |

| Asking if the patient has a way to manage and take their own medications. | 14 | |

| Educating and involving caregivers to support the patient to take medications correctly | 15 | |

| Education including medication name, reason for use, and potential side effects. | 20 | |

| A customized plan to help patients take medications at home in a way that works best for each patient’s individual needs. | 21 | |

| Teach back (tell and show me how) during medication education to ensure that patients understand the purpose, when/how to take, and safety concerns of medications. | 23 | |

| Medication lists and instructions for patients should be in layman’s language. | 25 | |

| Patients understanding how to reach out to health care providers with questions / concerns about medications. | 39 | |

| Patients understanding and “buy-into” the reason(s) for a change in medication before beginning that change. | 40 | |

| Patients understanding that they should always take their medications as prescribed and talk to their health care providers before starting, stopping or changing any medication. | 41 | |

| Reinforcing ongoing medication education for patients. | 67 | |

| Acknowledging that some medications cannot be stopped or reduced due to the underlying medical condition. | 72 | |

| Patient education that deprescribing can help improve patient’s health outcomes and it does not mean giving up on the patient. | 82 |

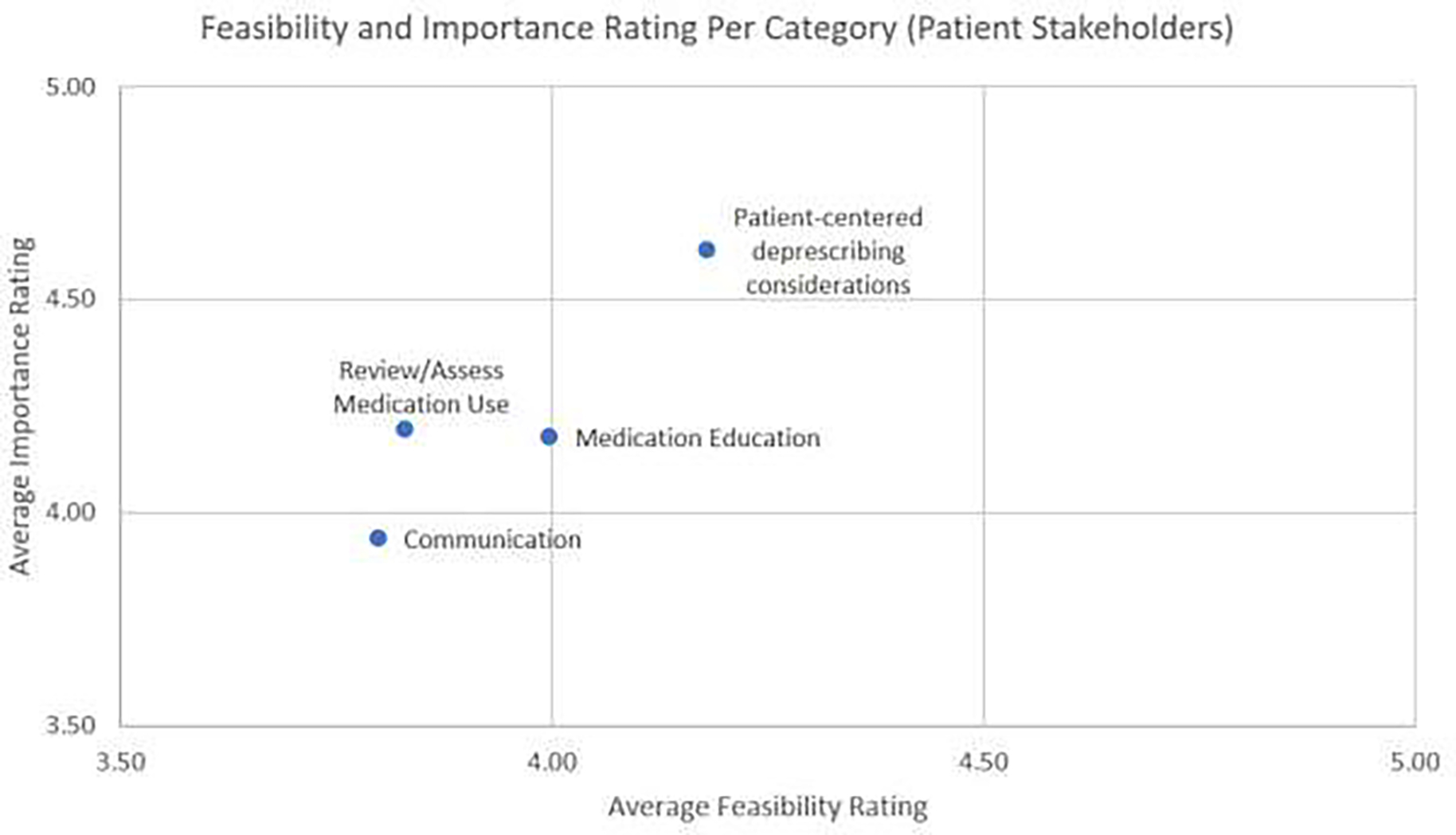

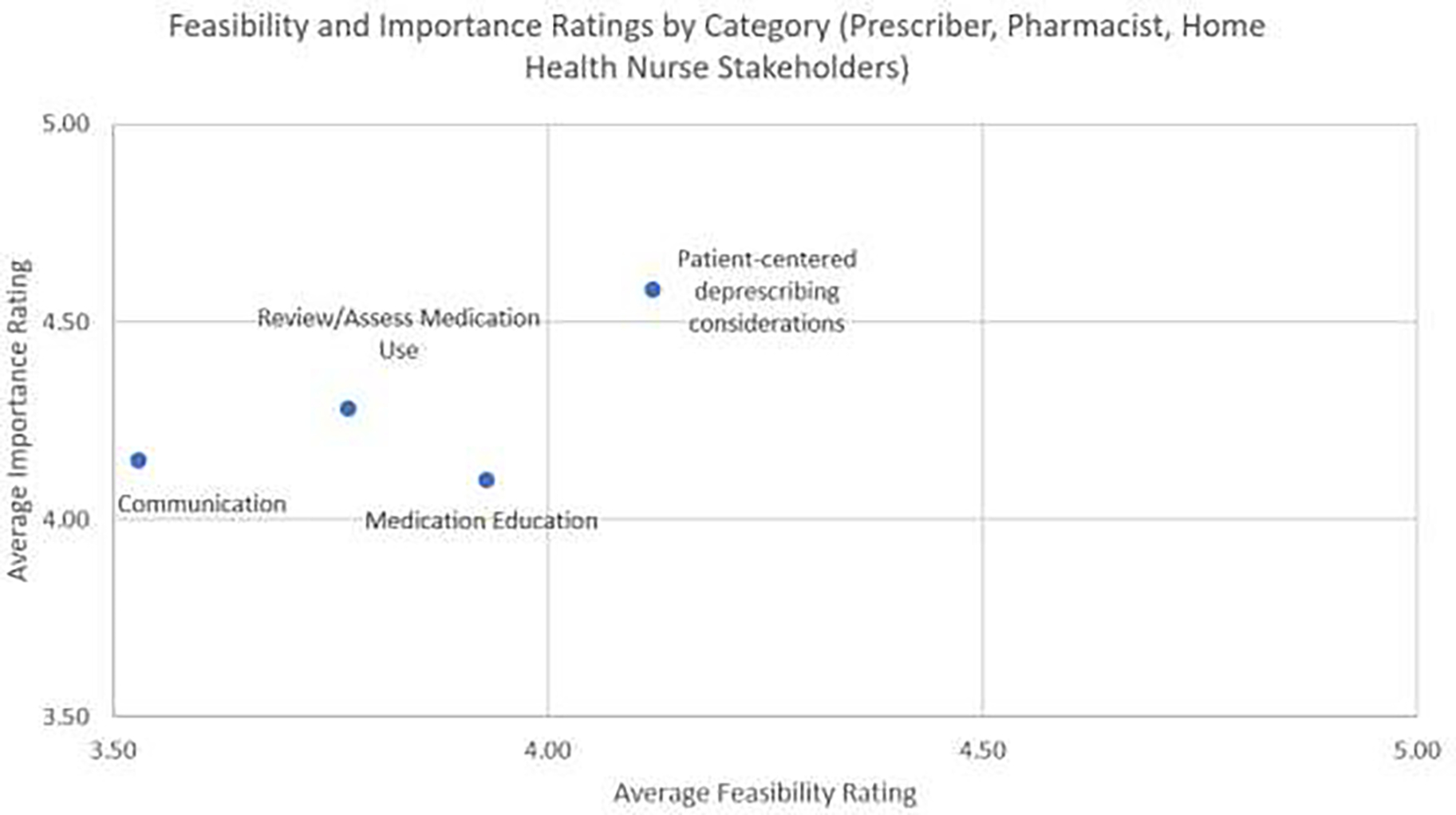

The average feasibility rating and importance rating of all the statements included in each category was calculated and plotted (Figures 2 & 3). Among the four categories, developing patient-centered, individualized deprescribing recommendations received the highest ratings of importance and feasibility, followed by review and assessment of medication use, followed by patient medication education and, lastly care team communication. Patient stakeholders (Figure 2) and clinician stakeholders (Figure 3) reported similar ratings of feasibility and importance in these categories. Next, we describe the statements included in each of the four categories in greater detail.

Figure 2.

Feasibility and Importance Ratings Per Category (Patient Stakeholders)

Figure 3.

Feasibility and Importance Ratings Per Category (Clinician Stakeholders) Appendix 1. Demographic Characteristics of Each Stakeholder Group

1. Review and Assessment of Medication Use

One PCP shared that because medication review and reconciliation in the hospital are often inaccurate, errors often occur on the patient’s medication list: “we get patients back on medications we’ve stopped a year ago, because it [medication] just gets pushed forward through the hospital system [without careful review]”. This indicates the importance of performing assessment and review of medication use for post-acute HHC patients.

To assess and review medication use for post-acute HHC patients, the following tasks were considered essential (Table 1), including 1) developing a complete, accurate and reconciled list of medications, such as by “pulling everything from their [patients’] cupboards, and comparing [their home medications] to the list we believe they should be taking”, 2) medication review that occurs continuously and not just a “one and done”, 3) assessing the patient’s symptoms and monitoring symptom changes, such as “seeing how they are doing and if we have concerns that we want to pass along [to PCPs]”, 4) assessing the patient’s medication adherence, “checking the [medication] bottles to see if they are at the same level to see how frequently they’re taking them”, 5) assessing the patient’s ability to manage their medications and relevant factors, such as health literacy, mental status, vision, manual dexterity (e.g., neuropathy) that can cause the patient “to be unable to see the pills” and/or “drop all the tiny pills on the floor”, and 6) assessing the patient’s home environment and available caregiver support at home, as well as 7) assessing social barriers that may affect the patient’s access to medications, such as language and health literacy, transportation, affordability, and connecting patients with resources to mitigate the impact of these social barriers on medication use, such as low-cost medication programs and referral to social workers.

One HHC nurse shared that “most of the time, patients just nod and say they understand, or they don’t have any questions. They may not understand it, but they’re not gonna say. They know the nurse is busy and rushed, and they are not gonna say, “I’m sorry, I can’t read that, or I don’t understand that.” Another HHC nurse noted financial barriers to medications, and a PCP noted discontinuity in medication review, preferring that it be done “every month and then maybe every three months”, by a multidisciplinary team with the physician and the pharmacist, as well as the patient and a family member, to “go over ‘This is how things are going. This is what we need to do. And these are the meds I’d like to stop, readjust, or change the doses.’”

2. Patient-Centered and Individualized Plan of Deprescribing

Stakeholders clearly emphasized the importance of patient-centered considerations in developing the deprescribing plan. They further described how patient-centeredness in deprescribing can manifest in three ways.

First, it is critical to align deprescribing decisions with the patient’s specific goals, needs, and preferences. Providers emphasized the need for deprescribing to improve patients’ quality of life, because at times “these medication lists just build and expand without someone with fresh eyes who can sit down there and look closely and figure out what’s needed”. One PCP shared, “In geriatrics, we really are focusing on the person in front of us, their quality of life, their ability to be as independent and functional as possible”. Another PCP shared, “if they had some illness 35 years ago, it’s often not applicable to how they’re feeling today. We really look at the person in the here and now and how we can tease out their symptoms and figure out if the medications are appropriate or if there are medications we need to add to help their symptoms. Ultimately, it is about doing what is the best for patients.”

Second, in the implementation of deprescribing, it is critical to have patient buy-in. One PCP commented, “sometimes you have to negotiate and say, “Well, I don’t think this is an appropriate medicine. I don’t think it’s helping you. Let’s cut it in half, and then we’ll work down. If you notice symptoms, you call me and let me know.” HHC nurses commented on the practice of “meeting the patients where they are” by providing tools to help patients take medications at home in a way that works best for each patient’s individual needs.

Third, stakeholders talked about the need to attend to social factors while making deprescribing decisions, especially factors that can affect the patient’s medication adherence and ability to administer or access medications. One HHC nurse shared, “In the inner city, people just can’t afford medications that they need. Some people don’t have cell phones and they can’t contact the doctor’s office [about medications]”. A PCP shared that “we see that [financial barrier] happen in a hospital where it’s like, “Okay. Here’s this great new inhaler. And you’re gonna use this for your COPD.” And then two months later, or even the next bill, they go to fill it at the pharmacy instead of getting it from the hospital, and they can’t afford it. They stop using it.”

3. Timely And Efficient Communication Among Members of The Care Team

Multiple clinicians are involved in the post-acute deprescribing process for patients during the transition from the hospital to HHC; they include PCPs, specialists, HHC nurses, and pharmacists. Therefore, it is important to maintain effective communication among the care team members for post-acute deprescribing to occur. A PCP commented, “there’re things that home healthcare [nurses], pharmacy, and the PCP can do together, and it’s just that there needs to be some person that continuously pushes and coordinates these services [in order for it] to happen in an organic way.”

Essential tasks related to communication shared by the stakeholders included HHC nurses initiating proactive communication with the PCP regarding issues related to polypharmacy identified during their home visits that increases patients’ risk for developing adverse events. An HHC nurse commented “Because we’re the only ones that truly go into the home and see how they take their medications, where their medications are scattered, so we’re really the main line of communication with the doctors’ offices.” Another HHC nurse suggested that having a direct route of communication between the PCP and HHC nurses can help the HHC nurse to receive timely feedback from the PCP, which can enable the HHC nurse to quickly solve problems while the HHC nurse is still present in the patient’s home.

Other tasks regarding communication needed for post-acute deprescribing include timely PCP follow-up with the patient regarding medications after hospital discharge, having clear guidelines for who within the care team responds to which of the patient’s questions, and having a platform for all members of the care team to communicate and share documents (e.g., medication lists) in real time. One PCP shared “We try to get a patient in within about 7 to 10 days after [hospital] discharge for a follow-up. That’s when we really spend the most time going over the medications, what was changed, what was added, what was taken away, and really reconcile their medication list from there.” PCPs, hospitalists, HHC nurses, and pharmacists consistently reported that having access to the same electronic health record system is crucial, as it facilitates communication and shared decision-making between the patient and members of the patient’s care team. One PCP shared: “We have the benefit of being on the same [electronic health] records. And we promote our patients to go there (hospital) because of that continuity and that ability to communicate and see all of those things. I’ve gotten several messages on e-record, saying, ‘We’ve got your patient in the hospital. They’re on this dose of this blood thinner, which we weren’t expecting. Is there a reason?’ They (hospitalists) ask the question, which I totally appreciate because that communication leads to us being able to move the needle forward without taking four steps back and trying something that’s been attempted before.”

4. Continued and Tailored Medication Education to Meet Patient Needs

Stakeholders reported that appropriate medication education for patients and caregivers is critical to facilitating post-acute deprescribing among HHC patients, and they specifically discussed the appropriate content and venue for medication education. Tailoring of patient education can be reflected in multiple ways, including providing an accurate, complete and reconciled medication list for each patient, teaching at a health literacy level that aligns with that of the patient, and supporting the patient with tools and in ways that are the most acceptable to the patient.

Statements regarding the content of medication education included: 1) ensuring that the patient has an accurate complete, and updated list of all the medications they are taking including prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, and supplements; 2) providing medication names with a rationale for why each is prescribed and indicated, timing, dose, and potential side effects; 3) using the teach-back technique to ensure the patient fully understands; and 4) employing ways to teach the patient about proper medication storage (e.g., not to store nitroglycerin on the window sill or insulin outside a refrigerator).

There were also statements about medication education aimed at improving the patient’s acceptance of deprescribing. One PCP noted the need to correct patients’ misconception that “there’s a pill to fix things and adding more medication is better for them”. PCPs also noted the importance of paying attention to language when introducing deprescribing to patients, so that they understand that deprescribing is intended to improve their health outcomes and “it [deprescribing] does not mean giving up on you”. Other statements related to deprescribing-specific education included a) understanding how a reduction of medication impacts the patient’s experience and alignment with the patient’s goals of care, and b) understanding to always take medications as prescribed and to talk to their health care providers before starting, stopping or changing any medication.

PCPs, pharmacists, patients and HHC nurses all agreed that medication education should be an ongoing process provided in layman’s language. One of the most common ways used by HHC nurses to teach HHC patients about medications is to directly ask patients how they are managing their medications. One HHC nurse shared that she usually observes how the patient manages their medications, such as “if they’re taking them out of the bottle or if they’re using a Mediset [medication organizer] and who fills that Mediset”. This nurse also shared that “if it is somebody that has a caregiver that manages [the medications], I’d like to grasp their knowledge on how often they’re doing it, how they know, [and] which medication to take.” A PCP shared about often using the teach-back technique with both the patient and the caregiver, especially when deprescribing for patients who are on a complicated medication regimen.

PCPs and pharmacists reported that patient education on medications is mostly PCP-driven. A PCP noted the need for adequate time to deliver effective teaching related to medications: “in an ideal situation, if we had enough staff, I would want to get more than just 15 minutes to think about these things [medication education] considerably, such as to see my patient have 1–1.5 hours with a pharmacist and me in the room with a patient’s family member present”. Yet, due to PCPs’ time constraints, it is helpful for pharmacists and HHC nurses to contribute to and/or reinforce patient education. One hospitalist shared that “at the end of the hospitalization”, for patients who take a lot of medications and are discharged to home with HHC, having “direct access to the home care nurse makes a big difference to [educating] older patients”. The hospitalist further added that working with HHC nurses enables her to “know an accurate situation of what is going on in a patient’s life”, to “have someone else besides me checking in [with the patient], giving them education, reminding them [that certain medications have been stopped]” and “reinforcing that multiple times in a week over the period of a month or more [while they are receiving HHC services] so that it is ingrained in the patient, and they are doing what they need to do”.

Besides teaching about medications, it is also important to provide patients with tangible tools and resources to support them with medication management and to facilitate deprescribing. Some important tasks related to providing patients with medication support tools include: 1) developing a customized plan to help patients take medications at home in a way that works best for each patient’s individual needs, 2) drafting a color-coded action plan related to medication side-effects (e.g., what to monitor, who to call, and when to visit the emergency department), 3) making a medication list for the patient to keep in their possession, 4) assessing social barriers and connecting patients with resources such as low-cost medication programs and professionals such as social workers, 5) helping the patient safely dispose of unnecessary medications (i.e., stopped or expired) in their home or at least separating deprescribed medications from their active medications to avoid medication errors, and 6) involving caregivers throughout the process.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study aims to explore key stakeholders’ perceptions of post-acute deprescribing for older patients in HHC, with two principal findings. First, four categories of tasks were identified by stakeholders as essential to post-acute care deprescribing in HHC: (a) review and assessment of medication use; (b) patent-centered and individualized plan of deprescribing; (c) timely and efficient communication among members of the care team; and (d) continuous and tailored medication education to meet patient needs. Second, rated by importance and feasibility, the most important themes that emerged across stakeholders were patient-centered deprescribing considerations, followed by medication education, medication review and assessment, and care team communication, in descending order.

Review and Assessment of Medication Use

Medication review and assessment are routinely included in deprescribing interventions and are of particular importance to post-acute deprescribing, due to the multiple changes to medication regimen that happen during hospitalization and upon discharge. Though medication review by itself is rarely an effective approach at improving patient outcomes,51 it is often the most critical initial step towards deprescribing.18 However, prescribers such as PCPs rarely have access to a comprehensive, accurate medication list, presenting a barrier to deprescribing.52–55 In an earlier study, we found that HHC nurses can be instrumental in obtaining an accurate, complete medication list during home medication review, which is a routine care process of HHC nurses56 called “brown bagging”,38 indicating that HHC nurses can facilitate deprescribing during the transition from hospital to home; this is especially true when the medication review conducted by HHC nurses is shared with providers to inform decision making on deprescribing (e.g., by using a well-structured format to highlight problems that may prompt deprescribing and if possible, by providing the HHC team and providers shared access to the patient’s electronic health records).

Patient-Centered and Individualized Plan of Deprescribing

Patient-centeredness requires providers to “know the patient” to align deprescribing with care and life goals that matter most to patients and their families, and the patient’s preferences and experience with medication use.43,57 It is important to develop a patient-centered deprescribing plan because preferences and experiences of medication use and care and life goals are often closely related to key rationales for deprescribing, including: 1) a patient’s experience with their medications (e.g., effectiveness, symptom control) and potential side effects; 2) barriers to medication adherence and management (e.g., complexity or frequency of dosing, language and financial barriers); 3) the degree to which the medication regimen aligns with the patient’s care and life goals; and 4) the patient’s acceptance of proposed deprescribing recommendations.

Because HHC nurses often make frequent visits to patients in their homes over an extended period of time (30–60 days or longer), they are in a position to “know the patient”58 and therefore can potentially help improve patient-centeredness in deprescribing recommendations. For example, deprescribing decision-making requires the prescriber to consider the patient’s symptoms, including changes in the symptom targeted by the medication of interest, new onset of symptoms that may suggest medication side effects and/or interactions, or withdrawal symptoms following the initial reduction or discontinuation of medications. Medication adherence is another rationale for deprescribing, because if a patient has poor adherence to certain medications due to side effects or unaffordable out-of-pocket costs, identifying nonadherence to medications provides an opportunity to prescribe alternative medications that are more likely to be accepted and adhered to by the patient. Because HHC nurses routinely monitor the patient’s symptoms58 and assess the patient’s medication intake, they can provide valuable insights for providers regarding symptoms and adherence that may facilitate appropriate deprescribing and/or potential prescribing of alternatives, when needed. It is important to note, however, that despite the unique advantages of HHC nurses at monitoring medication adherence and symptoms that can serve to prompt deprescribing decision-making of providers, HHC nurses are often new to the patients and do not have an established relationship at HHC admission. To help with continuity of care in HHC, it is important that when necessary, to have the same nurse visit the patient throughout the HHC episode.

Timely and Efficient Communication Among Members of The Care Team

Because health care professionals from multiple disciplines are often involved in the post-acute deprescribing process, having clear communication channels is important for these disciplines to collaborate. In this study, tasks related to care team communication were rated with the lowest levels of importance and feasibility relative to the other categories across all stakeholders. This finding was surprising because effective communication among care team members is necessary for interdisciplinary collaboration, including post-acute deprescribing. Though the reason for this finding is unclear, it may be related to the perceived low feasibility of communication due to gaps that exist across disciplines based on stakeholders’ experiences. Examples of common care team communication challenges include HHC nurses and PCPs making multiple attempts to reach each other, the lack of an easy way for PCPs to communicate with specialists, the shortage of pharmacists who work in post-acute care settings, and the lack of interoperability of electronic health record systems among members of the care team (e.g., HHC, PCP and specialists).38 To improve care team communication about post-acute care deprescribing, for example, the reconciled medication list generated by the HHC nurses during home visits should be shared with the patient’s PCP and other providers, such as by providing all members access to the same medication list in the electronic health record system and allow updates from HHC nurses to be reflected in this list. Alternatively, if paper format of medication list has to be used (as it is the case for most HHC agencies in practice), it can be faxed from the HHC team to the providers using a well-structured format to present the most important findings that facilitate providers to decide on deprescribing (e.g., medications with questions, associated symptoms, patient report of experience). In addition, it is important to note that six statements in the category of care team communication were rated with high importance and low feasibility (Table 2), although the overall category of care team communication was rated with low importance and low feasibility by stakeholders.

Table 2.

Selected Interview Statements in the upper left quadrant of Go-Zone (high-importance and low-feasibility)

| Category | Statements in Orange ZONE | # | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Review/assess | Primary care providers conducting regular medication reviews. | 7 | |

| Involving caregivers to provide information about the patient’s actual intake of medications, symptoms and side effects. | 6 | 1 | |

| Assessing social barriers and connecting patients with resources such as access to medications, low-cost medication programs, and personnel such as social workers. | 1 | 3 | |

| Primary care providers assessing the patient’s ability to take medicines correctly including health literacy, mental status, vision, manual dexterity, and nutrition. |

8 | 3 | |

| Pharmacist reviewing medications for high-risk patients and making recommendations to providers. | 5 | 6 | |

| Repeated assessment of the patient’s ability to take medications as prescribed and actual intake of medications | 8 | 6 | |

| Patientcentered deprescribing considerations | Patients being honest with their health care providers about feelings, needs, and concerns around medication, symptoms, sideeffects, etc. | 2 | 4 |

| Communication | Access to the same medication list for all members of the health care team. | 9 | |

| Timely primary care provider(s) follow-up regarding medications after hospital discharge. | 4 | 5 | |

| A shared communication and document-sharing platform available in real time for all members in the healthcare team. | 6 | 5 | |

| Reducing the “noise” and overload in documentation for primary care provider(s) to easily see medication information from home health care. | 0 | 6 | |

| Ways for different electronic health record systems to talk to each other to connect the data silos. | 2 | 6 | |

| Primary care provider offices coordinating communication about medications with other providers and home health care. | 4 | 6 |

Continued and Tailored Medication Education to Meet Patient Needs

Providing effective and adequate medication education for patients is key to decision making and implementation of deprescribing. Preferably, medication education in deprescribing should encompass all tasks that are essential to deprescribing, including medication use, a patient-centered and individualized deprescribing plan, and information about how to communicate with the care team. Yet, as noted in an earlier study,38 medication education is often limited to medication use, its effect is often less than ideal, and its frequency is less than adequate in post-acute HHC. Continuous medication education requires a sufficient number of HHC visits, which have been limited by recent payment reforms in HHC.59 In addition, other clinicians in the care team, particularly PCPs and pharmacists, have indispensable roles in providing patient education related to medication use. Yet, due to the limited engagement of pharmacists in post-acute deprescribing and the time constraints of PCPs,38 their roles in providing medication education during the transition from hospital to home are also limited.

Strengths and Limitations

First, although we recruited HHC clinicians from 12 U.S. states in consideration of the large geographic variation in HHC availability and service use,40,41 providers and patients were recruited locally in upstate New York, which may have affected the generalizability of findings. Rurality of residence, which may affect the patient’s access to post-acute HHC, was not surveyed in the demographic questionnaire and should be considered in future studies. Second, the sorting activity in concept mapping may still be cognitively challenging for some older adults, thus there is a likelihood that only the patients with relatively higher levels of cognitive function, or relatively intact cognition, participated in this study. To facilitate the concept mapping activities, we tailored the online instructions with all participants in mind, especially older patients with lower health literacy levels. In addition, after learning from several participants about their difficulty following the online concept mapping instructions, we created a video tutorial as a resource to all online participants to assist with the concept mapping activity. Last, it is important to note that these four categories of post-acute deprescribing tasks identified in this study are not mutually exclusive and they may overlap, such as between patient-centered deprescribing and tailored patient education on medication. In addition, the categorization of statements was based on stakeholders’ collective grouping of the statements and there may be other ways to categorize them other than what was presented here.

The strengths of the study include: 1) combined use of individual qualitative interview and group-based concept mapping, which yielded both individual perspectives and group-level perceptions of key stakeholders towards post-acute care deprescribing; 2) the recruitment of key stakeholders from 12 U.S. states, thus bolstering the geographic representation of findings; 3) purposeful attempts to recruit older HHC patients from under-represented racial/ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds (n=3). We also made accommodations for individuals without Internet and email access to participate in the study, such as by mailing paper copies of concept mapping materials to participants and providing additional staff support (1–3 hours per patient) to go over the concept mapping activities over the phone with the patients who did not have access to Internet at home.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Policy

Our study has shown that tasks in post-acute care deprescribing perceived of high importance by stakeholders include 1) medication review and assessment, 2) developing a patient-centered and individualized deprescribing plan, 3) clear communication channels between patient and clinicians and among clinicians in the care team, and 4) tailored and continuous patient education on medications. Thus, deprescribing practice in post-acute care should include these tasks. For example, deprescribing recommendations should align the treatment regimen with goals that matter most to patients and their families (patient-centeredness), preferably including communication with prescribers, patients and caregivers about deprescribing recommendations whenever possible to support shared decision-making (communication). In particular, patient-centered care is important to improving clinical practice in building an age-friendly health care system. Thus deprescribing, as an essential care process, should include considerations of not only the “Medications”, but also “Mentation”, “Mobility” and “What Matters Most”.57 To facilitate communication and information sharing among clinicians within the care team about deprescribing, it may be useful to provide an accurate list of medications and related problems, preferably structured to match patients’ needs60,61 to facilitate medication review and education, and to make this list accessible to all members of the care team to promote shared communication about deprescribing recommendations (communication). Dedicated reimbursement structures should be developed to support PCPs, pharmacists and HHC nurses to provide high-quality care for tasks essential to post-acute deprescribing. Thus, the focus of post-acute deprescribing should be to create a synchronous implementation of these tasks by the appropriate care team members.

CONCLUSIONS

Providing patients with continuous medication education, conducting medication review and assessment, and ensuring effective communication among the care team members and patient-centered considerations are essential tasks for successful deprescribing during the hospital-to-home transition. Members of the care team, including HHC nurses, PCPs, and pharmacists as well as specialists, should be supported with the necessary information, resources and tools to inform care processes and effectively collaborate in deprescribing, such as to determine responsibility for each essential task during such care transitions where time and support at often limited for patients and their clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Selected Interview Statements in lower right quadrant of Go-Zone (low-importance and high-feasibility)

| Category | Selected Interview Statements in Yellow ZONE | |

|---|---|---|

|

Medication review/assess |

Home health care nurses brown-bagging (gathering) and reviewing all medications in the patient’s home. | 0 |

| Home Health Care nurses assessing the patient’s cultural perspectives towards medication use. | 5 | |

| Communication | Home health care nurses using the Situation-BackgroundAssessment-Recommendation structure to communicate with primary care provider(s) about medications | 9 |

| Education | Patient education that more medications are not always better. | 2 |

| Medication education for patients and caregivers provided by home health care nurses. | 7 | |

| A color-coded action plan printed out related to medication side-effects (who to call when, or when to visit the emergency department). |

2 | |

| Teaching on how to correctly store medications (e.g., not to store nitroglycerin on the window sill). | 4 | |

| A list of medications for the patient to keep in their wallet / purse. | 6 | |

| Home health care nurses receiving orientation and ongoing education about pharmacology, high-risk medications and related symptom management. | 6 | |

| A comprehensive checklist to remind home health care nurses to complete all medication-related care processes. | 7 |

Table 4.

Selected Interview Statements in lower lef quadrant of Go-Zone (low-importance and low-feasibility)

| Category | Statements in Orange ZONE | |

|---|---|---|

| Medication Review/assess |

Pharmacists conducting regular medication reviews | |

| Primary care providers assessing the patient’s cultural perspectives towards medication use. | 6 | |

| Telehealth for providers to assess patient’s condition and functionality in the home setting. | 6 | |

| Communication | Home health care nurses help patients communicate with their primary care provider(s). | 4 |

| Pharmacists to help home health care nurses with questions regarding medications. | 8 | |

| Efforts to reduce documentation burden in home health care regarding medications. | 9 | |

| Having the same home health care nurse seeing the same patient at regular intervals over a period of time. | 0 | |

| Primary care provider(s) driving the care for all patients. | 1 | |

| Primary care provider(s) leading discussions with other providers about medications. | 2 | |

| Having providers document the rationale for prescribing decisions and being able to see each other’s comments. | 5 | |

| Home health care offices coordinating communication about medications with providers. | 3 | |

| The opportunity for home health care nurse to use telehealth such as video conferencing to communicate with providers while visiting the patient’s home. | 3 | |

| Technological support for patients to use telehealth such as video conferencing to communicate with providers. | 4 | |

| Ways to use telehealth to improve access to care to promote health equity. | 5 | |

| Ways to use telehealth to update medication lists for patients. | 8 | |

| Ways to use telehealth to get everyone together on a video visit including the patient, caregiver, and his/her providers. | 9 | |

| Ways to recognize and best utilize primary care provider(s)’s limited time. | 0 | |

| Ways to recognize and best utilize home health care nurse’s limited time. | 1 | |

| Education | Helping the patient to dispose of unnecessary medications in the house. | 3 |

| Medication education for patients and caregivers provided by pharmacist. | 8 | |

| Medication education for patients and caregivers provided by primary care providers. | 9 | |

| Home health care nurses helping patients obtain needed medications during the transition from hospital to home. | 5 | |

| Primary care provider(s) driving the medication education for patients. | 3 | |

| Ways to use telehealth to provide patient education. | 7 |

Highlights.

Deprescribing needs for post-acute home health care include assessment and review of medication use, patient-centered deprescribing recommendations, effective and continuous patient education, and timely and efficient interdisciplinary communication and collaboration among care team members.

Developing patient-centered deprescribing practice was considered the most feasible and important by stakeholders.

Communication was considered essential to post-acute care deprescribing during the individual interviews, yet it was rated the lowest in feasibility and importance by stakeholders in group-based concept mapping. Such a conflict may be due to challenges and frustration that clinicians experience with communication in real life.

Multiple routine tasks of stakeholders, including home health care nurses, primary care providers and pharmacists, are foundational for deprescribing in post-acute care.

Disclosure of Funding Support

This study was conducted with the support of the following funders: U.S. Deprescribing Research Network (1R24AG064025; JW: 2021–2022 Pilot Award) and Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation (JW: 2021 Home Health Care Research Funding). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the funders. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analyses, or interpretation of results.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest

Jinjiao Wang received grants from the NIA funded U.S. Deprescribing Research Network and the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. Sandra Simmons received consulting fee from Abt Associates and participated on the data safety monitoring or advisory board of the CAPABLE study, Prepare for your Diabetes Care, and the Porchlight Project. Amanda Mixon received grants from VA HSR&D and NIA, and consulting fees from American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Other authors reported no conflicts of interest pertinent to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Shen JY, Yu F, Conwell Y, Nathan K, Shah AS, Simmons SF, Li Y, Ramsdale E, Caprio TV. Medications Associated with Geriatric Syndromes (MAGS) and Hospitalization Risk in Home Health Care Patient [In Press]. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao Y, Shao H, Bishop TF, Schackman BR, Bruce ML. Inappropriate Medication in Home Health Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):491–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao Y, Shao H, Bishop TF, Schackman BR, Bruce ML. Inappropriate medication in a national sample of US elderly patients receiving home health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(3):304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon KT, Choi MM, Zuniga MA. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients receiving home health care: a retrospective data analysis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(2):134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer-Massetti C, Meier CR, Guglielmo BJ. The scope of drug-related problems in the home care setting. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(2):325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsao CH, Tsai CF, Lee YT, et al. Drug Prescribing in the Elderly Receiving Home Care. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(2):134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotton BP, Lohman MC, Brooks JM, et al. Prevalence of and Factors Related to Prescription Opioids, Benzodiazepines, and Hypnotics Among Medicare Home Health Recipients. Home healthcare now. 2017;35(6):304–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cahir C, Bennett K, Teljeur C, Fahey T. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(1):201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill-Taylor B, Sketris I, Hayden J, Byrne S, O’Sullivan D, Christie R. Application of the STOPP/START criteria: a systematic review of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, and evidence of clinical, humanistic and economic impact. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38(5):360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraf AA, Petersen AW, Simmons SF, et al. Medications associated with geriatric syndromes and their prevalence in older hospitalized adults discharged to skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):694–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez T, Moriarty F, Wallace E, McDowell R, Redmond P, Fahey T. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people in primary care and its association with hospital admission: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2018;363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohman MC, Cotton BP, Zagaria AB, et al. Hospitalization Risk and Potentially Inappropriate Medications among Medicare Home Health Nursing Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1301–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murtaugh C, Peng T, Totten A, Costello B, Moore S, Aykan H. Complexity in geriatric home healthcare. J Healthc Qual. 2009;31(2):34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Home Health Quality Measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Home-Health-Quality-Measures. Published 2019. Updated December 17, 2019. Accessed January 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muhlack DC, Hoppe LK, Weberpals J, Brenner H, Schöttker B. The Association of Potentially Inappropriate Medication at Older Age With Cardiovascular Events and Overall Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(3):211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodward MC. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2003;33(4):323–328. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urfer M, Elzi L, Dell-Kuster S, Bassetti S. Intervention to Improve Appropriate Prescribing and Reduce Polypharmacy in Elderly Patients Admitted to an Internal Medicine Unit. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKean M, Pillans P, Scott IA. A medication review and deprescribing method for hospitalised older patients receiving multiple medications. Intern Med J. 2016;46(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naunton M, Peterson GM. Evaluation of Home-Based Follow-Up of High-Risk Elderly Patients Discharged from Hospital. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2003;33(3):176–182. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saeed D, Carter G, Parsons C. Interventions to improve medicines optimisation in frail older patients in secondary and acute care settings: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibrahim K, Cox NJ, Stevenson JM, Lim S, Fraser SDS, Roberts HC. A systematic review of the evidence for deprescribing interventions among older people living with frailty. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(4):738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloomfield HE, Greer N, Linsky AM, et al. Deprescribing for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3323–3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marvin V, Ward E, Poots AJ, Heard K, Rajagopalan A, Jubraj B. Deprescribing medicines in the acute setting to reduce the risk of falls. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(1):10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitkälä KH, Juola AL, Kautiainen H, et al. Education to reduce potentially harmful medication use among residents of assisted living facilities: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of Deprescribing Interventions in Older Hospitalised Patients on Prescribing and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Randomised Trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(4):303–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):583–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, Negm A, Peters R, Wong EKC, Holbrook A. Deprescribing fall-risk increasing drugs (FRIDs) for the prevention of falls and fall-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e035978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Runganga M, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Multiple medication use in older patients in post-acute transitional care: a prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1453–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamble J-M, Hall JJ, Marrie TJ, Sadowski CA, Majumdar SR, Eurich DT. Medication transitions and polypharmacy in older adults following acute care. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calkins DR, Davis RB, Reiley P, et al. Patient-physician communication at hospital discharge and patients’ understanding of the postdischarge treatment plan. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(9):1026–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A data book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. Washington, DC: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callahan CM, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Shen JY, Yu F, et al. Challenges in Deprescribing Among Older Adults in Post-Acute Care Transitions to Home. J Gen Intern Med. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reschovsky JD, Ghosh A, Stewart KA, Chollet DJ. Durable Medical Equipment And Home Health Among The Largest Contributors To Area Variations In Use Of Medicare Services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Leifheit-Limson EC, Fine J, et al. National Trends and Geographic Variation in Availability of Home Health Care: 2002–2015. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1434–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saldaña J The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasilevskis EE, Shah AS, Hollingsworth EK, et al. A patient-centered deprescribing intervention for hospitalized older patients with polypharmacy: rationale and design of the Shed-MEDS randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green AR, Boyd CM, Gleason KS, et al. Designing a Primary Care-Based Deprescribing Intervention for Patients with Dementia and Multiple Chronic Conditions: a Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3556–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott S, Twigg MJ, Clark A, et al. Development of a hospital deprescribing implementation framework: A focus group study with geriatricians and pharmacists. Age Ageing. 2020;49(1):102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linsky A, Gellad WF, Linder JA, Friedberg MW. Advancing the Science of Deprescribing: A Novel Comprehensive Conceptual Framework. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(10):2018–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Huberman MA, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patton MQ. Qual Res & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. In: Thousand oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ayres L, Kavanaugh K, Knafl KA. Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(6):871–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Vol 41: Sage publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huiskes VJ, Burger DM, van den Ende CH, van den Bemt BJ. Effectiveness of medication review: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abou J, Crutzen S, Tromp V, et al. Barriers and Enablers of Healthcare Providers to Deprescribe Cardiometabolic Medication in Older Patients: A Focus Group Study. Drugs Aging. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ailabouni NJ, Nishtala PS, Mangin D, Tordoff JM. Challenges and Enablers of Deprescribing: A General Practitioner Perspective. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151066–e0151066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cullinan S, Hansen CR, Byrne S, O’Mahony D, Kearney P, Sahm L. Challenges of deprescribing in the multimorbid patient. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2017;24(1):43–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, Simmons SF, Maxwell CA, Schlundt DG, Mion LC. Home Health Nurses’ Perspectives and Care Processes Related to Older Persons with Frailty and Depression: A Mixed Method Pilot Study. J Community Health Nurs. 2018;35(3):118–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, Podsiadly EJ, Caprio TV, Nathan K, Yu F, Ramsdale E, Fick D, Mixon AM, & Simmons SF. How “Age-Friendly” Are Deprescribing Interventions? A Scoping Review of Deprescribing Trials. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 Suppl 1:123–138. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Simmons S, Maxwell CA, Schlundt DG, Mion L Home health nurses’ perspectives and care processes related to older persons’ frailty and depression: A mixed method pilot study. J Community Health Nurs. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Home Health Patient-Driven Groupings Model. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HomeHealthPPS/HH-PDGM.html; https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2020-24146.pdf Published 2020. Updated December 4, 2020. Accessed Februrary 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, Shen JY, Podsiadly EJ, Conwell Y, Caprio TV, Nathan K, Yu F, Ramsdale EE, Fick DM, & Simmons SF. Considerations of Age-Friendly 4M Principles in Deprescribing Interventions - A Scoping Review. 2022 Annual Network Meeting of the U.S. Deprescribing Research Network; 2022; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The Age-Friendly Health System Imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.