Abstract

Using the publicly available Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database from 2003-2019, we evaluated associations between decedent characteristics and location of death for patients with ovarian malignancy. We found that Black, Native American, Asian American, and Hispanic patients were more likely to die in hospitals than White patients, despite an overall reduction in hospital deaths and an overall increase in hospice facility deaths. Additionally, patients with lesser educational attainment were more likely to die in nursing facilities and less likely to die in hospice facilities. Although there may be some contribution from cultural preferences, these findings may represent disparities in access to palliative care affecting racial/ethnic minoritized people with cancer.

Precis

Patients with ovarian cancer who identify as racial minorities and those with lower educational attainments are more likely to die in hospitals, uncovering notable disparities in death outside an institutional setting.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer accounts for more deaths than any other cancer of the female reproductive system. The paucity of specific symptoms and absence of effective screening options contributes to late-stage diagnosis in over 75% of patients, often with complications requiring sustained symptom management.1 Location of death can be an essential clinical consideration for these patients given associations with symptom amelioration, emotional support, and quality of death.2 Additionally, the majority of women with ovarian cancer receive aggressive end-of-life care following prolonged treatment courses.3 Thus, understanding patterns and potential disparities in location of death is critical to empower patient-centered decision making in advance care planning.

METHODS

We analyzed trends and disparities in location of death using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Range Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database. All women in the United States between 2003 and 2019 with ovarian malignancy as the primary cause of death were included. Multivariable logistic regression evaluated associations between decedent characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education) and place of death. Location of death included hospital, home, nursing facility, hospice facility, and outpatient medical facility/emergency department. Data are reported as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval.

RESULTS

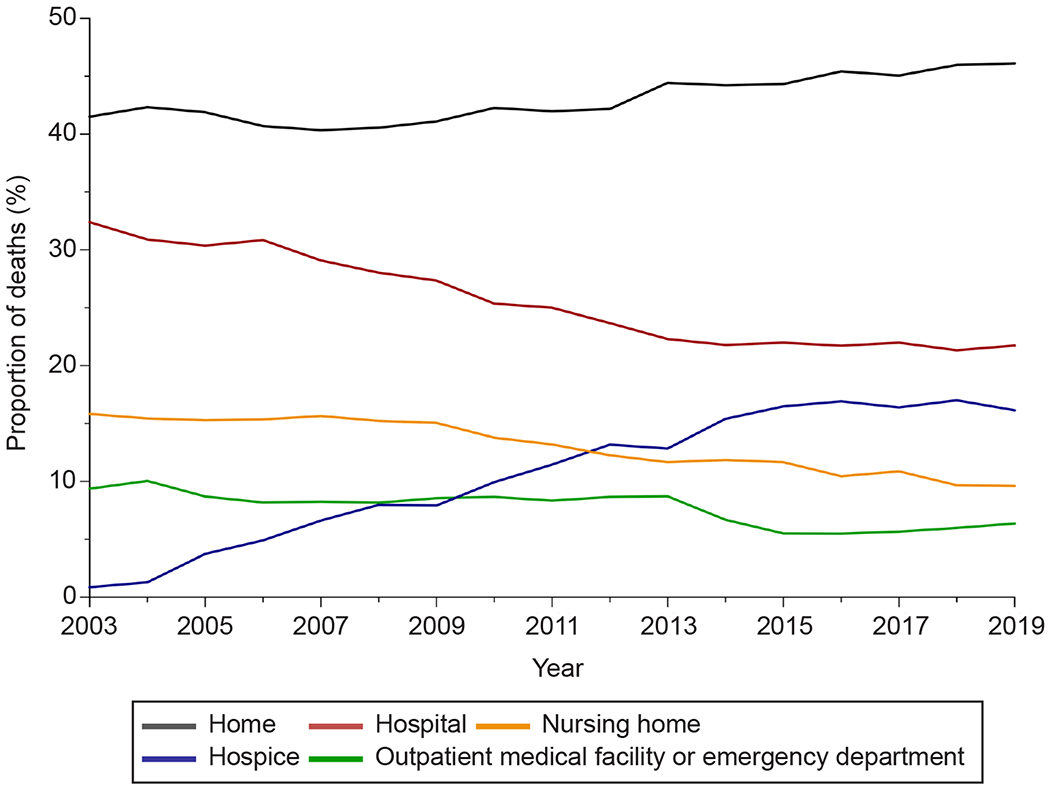

Between 2003 and 2019, 237,069 patients died from ovarian cancer. Over time, the proportion of home and hospice deaths increased while deaths occurring in hospitals, nursing homes, and outpatient medical facilities/EDs decreased (Figure 1) (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). Patients from racial/ethnic minority groups were more likely to die in the hospital than White patients (Black patients: aOR: 1.69 [95% CI: 1.63-1.74], American Indian patients: 1.47 [1.30-1.66], Asian patients: 1.54 [1.46-1.62]; P<0.001). Black (0.93 [0.89-0.98]), American Indian (0.57 [0.45-0.72]), and Asian (0.66 [0.60-0.72]) patients had lower odds of hospice death compared to White patients (P<0.001). Similarly, Hispanic patients were more likely to die in the hospital (1.24 [1.19-1.28]) and less likely to die in hospice facilities (0.93 [0.88-0.98]) than non-Hispanic patients (P<0.001). Patients with a college education had increased odds of home (1.09 [1.08-1.12]) and hospice (1.18 [1.15-1.21]) death and lower odds of hospital (0.90 [0.88-0.92]) and nursing facility (0.83 [0.80-0.85]) death than those without a college education (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Trends in location of deaths for individuals with ovarian cancer between 2003 and 2019.

Table 1:

Association Between Decedent Characteristics and Location of Death, 2003-2019.

| aOR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic (N = 241,971) | Hospital vs All Other Locations of Death | Home vs All Other Locations of Death | Nursing Facility vs All Other Locations of Death | Hospice Facility vs All Other Locations of Death | Outpatient Medical Facility/ED vs All Other Locations of Death |

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤64 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 65-74 | 0.83 (0.81-0.85) (***) | 1.07 (1.05-1.09) (***) | 1.46 (1.40-1.52) (***) | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) (***) |

| 75-84 | 0.68 (0.66-0.69) (***) | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) (***) |

2.31 (2.23-2.40) (***) | 0.89 (0.86-0.92) (***) | 0.92 (0.88-0.96) (***) |

| ≥85 | 0.43 (0.41-0.45) (***) | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) (*) | 3.53 (3.39-3.67) (***) | 0.78 (0.75-0.82) (***) | 0.98 (0.89-1.07) |

| Race | |||||

| American Indian | 1.47 (1.30-1.66) (**) | 0.98 (0.87-1.10) | 0.83 (0.69-1.01) | 0.57 (0.45-0.72) (**) | 0.86 (0.68-1.08) |

| Asian | 1.54 (1.46-1.62) (***) | 0.89 (0.85-0.94) (**) | 0.74 (0.67-0.81) (***) | 0.66 (0.60-0.72) (***) | 0.98 (0.89-1.07) |

| Black | 1.69 (1.63-1.74) (***) | 0.74 (0.72-0.76) (***) | 0.67 (0.65-0.71) (***) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) (***) | 1.12 (1.07-1.18) (***) |

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Hispanic | 1.24 (1.19-1.28) (***) | 1.15 (1.11-1.19) (***) | 0.48 (0.45-0.52) (***) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) (**) | 0.89 (0.83-0.95) (**) |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Not married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Married | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 1.56 (1.53-1.58) (***) | 0.47 (0.46-0.49) (***) | 0.90 (0.88-0.93) (***) | 0.68 (0.66-0.71) (***) |

| Education | |||||

| High school or less | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Some college or more | 0.90 (0.88-0.92) (***) | 1.09 (1.08-1.12) (***) | 0.83 (0.80-0.85) (***) | 1.18 (1.15-1.21) (***) | 1.02 (1.00-1.06) (***) |

Age, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education were retained as covariates in all final regression models.

= p < 0.001,

= p < 0.01,

= p < 0.05

DISCUSSION

An increasing proportion of patients with ovarian cancer are dying outside acute care facilities, with under half dying at home and approximately one-third dying in hospice. However, racial and ethnic minority groups continue to be more likely to die in the hospital than White patients. Non-white decedents are generally 5% more likely to die in hospital settings and half as likely to die in hospice facilities than their White counterparts. Decedents with lower educational attainment were also more likely to die at a hospital or nursing facility. Our research uncovers notable disparities in death outside an institutional setting, corroborating analyses from previous studies.4,5

Patients with ovarian cancer may benefit from culturally sensitive end-of-life communication and advanced care planning.5 Patient place of death preference is unique to their individual circumstances and belief systems, as faith, symptom burden, social support, socioeconomic status, and geography may affect the delivery of quality end-of-life care. Hospital death may actually be preferable for patients with limited family support and who cannot afford additional caregivers. We urge clinicians to empower and support patient-driven decision making by discussing both institutional and non-institutional end-of-life options with their patients and families.

Supplementary Material

Financial Disclosure

Edward Christopher Dee and Fumiko Chino reports money was paid to their institution from the NIH/NCI, Support Grant P30 CA008748. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herrinton Lisa J., et al. “Complications at the end of life in ovarian cancer.” Journal of pain and symptom management 34.3 (2007): 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puechl Allison M., et al. “Place of death by region and urbanization among gynecologic cancer patients: 2006–2016.” Gynecologic oncology 155.1 (2019): 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullins MA, Uppal S, Ruterbusch JJ, Cote ML, Clarke P, Wallner LP. Physician Influence on Variation in Receipt of Aggressive End-of-Life Care Among Women Dying of Ovarian Cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;18(3):e293–e303. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chino F, Kamal A, Leblanc T, Zafar S, Suneja G, Chino J. Place of death for patients with cancer in the United States, 1999 through 2015: Racial, age, and geographic disparities. Cancer. 2018;124(22):4408–4419. doi: 10.1002/CNCR.31737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knutzen KE, Sacks OA, Brody-Bizar OC, et al. Actual and Missed Opportunities for End-of-Life Care Discussions With Oncology Patients: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113193. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.