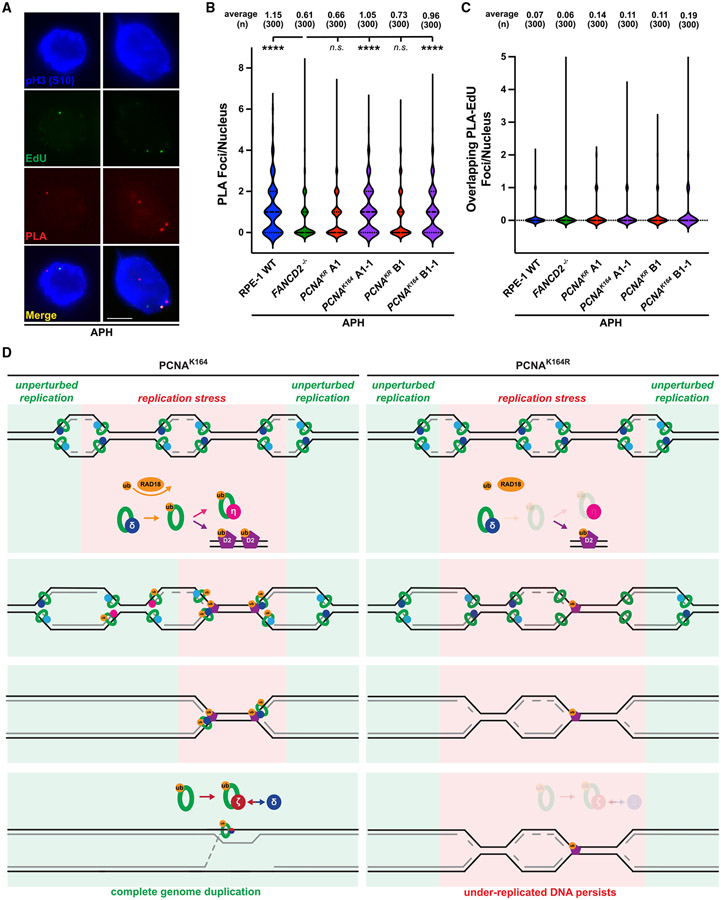

Figure 6. PCNA K164 ubiquitination promotes its colocalization with FANCD2 in mitotic nuclei.

(A) Representative images of phospho-H3 S10-stained nuclei (blue), EdU foci (green), and PLA foci (red) from APH-treated RPE-1 cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

(B) PLA foci quantification from at least three biological replicates in RPE-1 wild-type (blue), FANCD2−/− (green), PCNAK164R (maroon), and reverted PCNAK164 (purple) cells treated with 300 nM APH. Number (n) of nuclei quantified is listed. Significance was calculated by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison test with ****p > 0.001.

(C) Quantification of overlapping PLA and EdU foci from at least three biological replicates in RPE-1 wild-type (blue), FANCD2−/− (green), PCNAK164R (maroon), and reverted PCNAK164 (purple) cells treated with 300 nM APH. Number (n) of nuclei quantified is listed.

(D) In wild-type (PCNAK164) cells (left), PCNA is ubiquitinated at K164 in response to replication stress by RAD18. During S phase, this facilitates the switch from processive DNA polymerase to TLS polymerases (for example, Pol η) to complete DNA synthesis. At alternative loci, ubiquitinated PCNA promotes the ubiquitination and chromatin association of FANCD2. During G2/M phase, PCNA recruits subunits of TLS Pol ζ to FANCD2-marked foci to initiate MiDAS and then facilitates processive replication through association with components of Pol δ. In mutant (PCNAK164R) cells (right), PCNA ubiquitination is impaired. Subsequently, TLS polymerase and FANCD2 recruitment to stressed replication forks is reduced in S and G2/M phases, causing the persistence of under-replicated genomic loci.