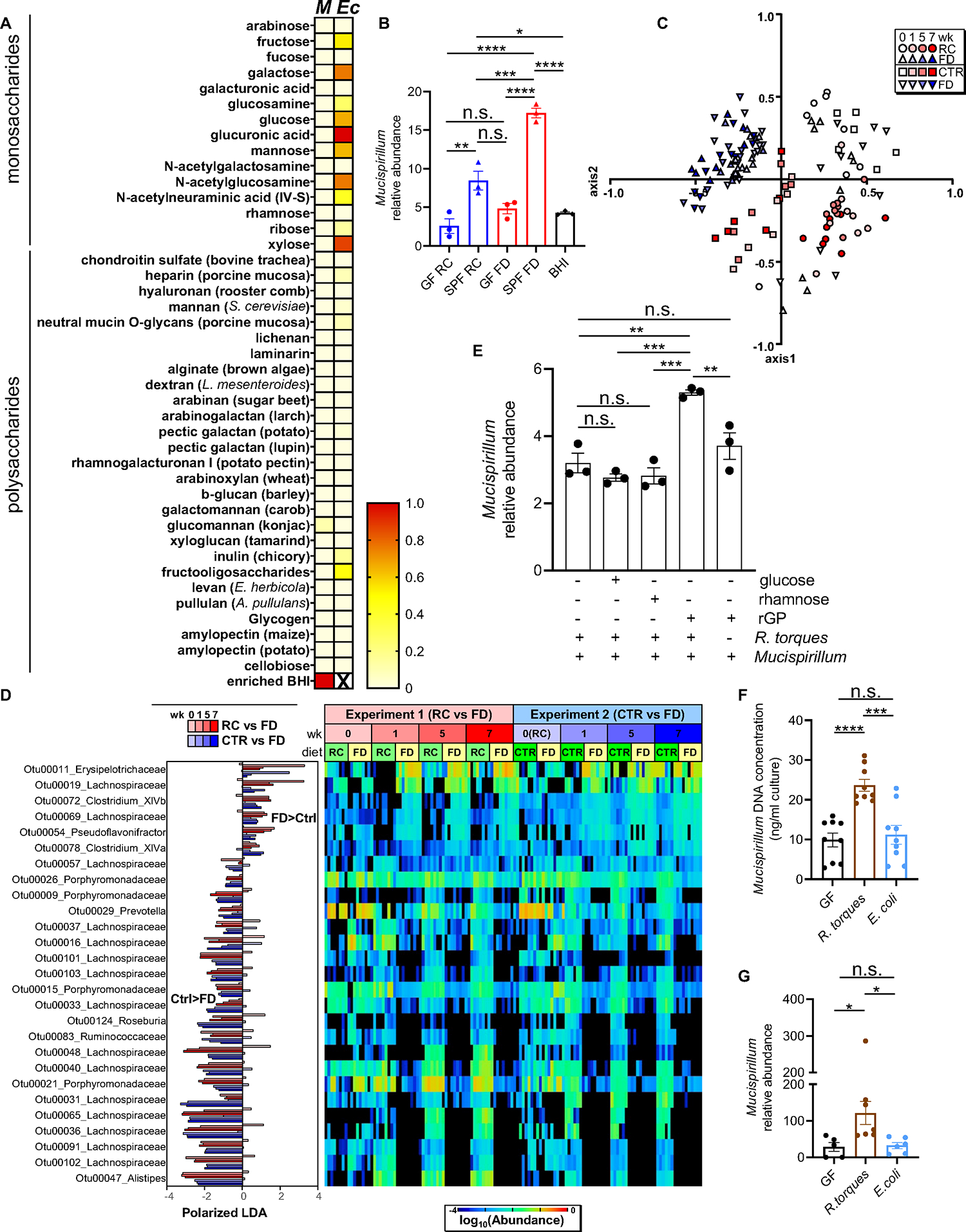

Figure 4. Mucin-degrading microbes promote Mucispirillum growth.

(A) Heat map showing normalized growth values of Mucispirillum (M) or E. coli (Ec) (enriched BHI, positive control for Mucispirillum). (B) Mucispirillum growth in the presence of either GF- or SPF-derived supernatants (enriched BHI (BHI), positive control). Mucispirillum abundance was normalized to the universal 16S rRNA gene. (C) NMDS plot of θYC β-diversity indexes of fecal microbiota from Tac-DKO mice fed either RC (circles), CTR (squares) or FD (triangles) for up to 7 weeks. (D) OTUs differentially abundant in fecal microbiota of Tac-DKO mice fed the FD or the control diets (RC or CTR) shown with LDA values of LEfSe with p<0.05, false discovery rate <0.05 and maximal abundance cutoff <1%. (E) Mucispirillum and R. torques co-culture in custom chopped meat broth in the presence of rectal glycoproteins (rGP), glucose or rhamnose. Mucispirillum abundance was normalized to the universal 16S rRNA gene. (F) Mucispirillum growth in the presence of supernatants derived from GF, R. torques-monocolonized and E. coli-monocolonized mice. (G) Abundance of Mucispirillum in GF, R. torques-monocolonized and E. coli-monocolonized mice was normalized to the universal 16S rRNA gene.

Each symbol represents one mouse, except for panel B, in which each dot represents data pooled from 3 individual mice. Data are mean ± SEM, representative of at least two independent experiments, n= 5–9 per group. *p< 0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; n.s. not significant by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test. See also Figures S4 and S5; Tables S2, S3 and S7.