Abstract

The significant regulatory role of palmitoylation modification in cancer-related targets has been demonstrated previously. However, the biological functions of Nrf2 in stomach cancer and whether the presence of Nrf2 palmitoylation affects gastric cancer (GC) progression and its treatment have not been reported. Several public datasets were used to look into the possible link between the amount of palmitoylated Nrf2 and the progression and its outcome of GC in patients. The palmitoylated Nrf2 levels in tumoral and peritumoral tissues from GC patients were also evaluated. Both loss-of-function and gain-of-function via transgenic experiments were performed to study the effects of palmitoylated Nrf2 on carcinogenesis and the pharmacological function of 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) on the suppression of GC progression in vitro and in vitro. We discovered that Nrf2 was palmitoylated in the cytoplasmic domain, and this lipid posttranslational modification causes Nrf2 stabilization by inhibiting ubiquitination, delaying Nrf2 destruction via the proteasome and boosting nuclear translocation. Importantly, we also identify palmitoyltransferase zinc finger DHHC-type palmitoyltransferase 2 (DHHC2) as the primary acetyltransferase required for the palmitoylated Nrf2 and indicate that the suppression of Nrf2 palmitoylation via 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP), or the knockdown of DHHC2, promotes anti-cancer immunity in vitro and in mice model-bearing xenografts. Of note, based on the antineoplastic mechanism of 2-BP, a novel anti-tumor drug delivery system ground 2-BP and oxaliplatin (OXA) dual-loading gold nanorods (GNRs) with tumor cell membrane coating biomimetic nanoparticles (CM@GNRs-BO) was established. In situ photothermal therapy is done using near-infrared (NIR) laser irradiation to help release high-temperature-triggered drugs from the CM@GNRs-BO reservoir when needed. This is done to achieve photothermal/chemical synergistic therapy. Our findings show the influence and linkage of palmitoylated Nrf2 with tumoral and peritumoral tissues in GC patients, the underlying mechanism of palmitoylated Nrf2 in GC progression, and novel possible techniques for addressing Nrf2-associated immune evasion in cancer growth. Furthermore, the bionic nanomedicine developed by us has the characteristics of dual drugs delivery, homologous tumor targeting, and photothermal and chemical synergistic therapy, and is expected to become a potential platform for cancer treatment.

Keywords: DHHC2, Stomach cancer, Palmitoylation, 2-Bromopalmitate, Dual-drug loading gold nanorods (GNRs) system

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- DHHC2

Zinc finger DHHC-type palmitoyltransferase 2

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- STATs

Signal transducer and activator of transcription family

- NRF2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- KEAP1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-B

- MAPKs

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- SRCC

Signet-ring cell carcinoma

- GC

Gastric cancer

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome database

- GNRs

Gold nanorods

- OXA

Oxaliplatin

- 2- BP

2-bromopalmitate

- HA

Hyaluronic acid

- CM

Cytomembrane

- TEM

Transmission electron microscope

1. Introduction

Stomach cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the world, and it is well established that about 60 % of new signet-ring cell carcinoma cases occur in East Asia [1,2]. Early gastric cancer clinically has no characteristic features, and diagnosis primarily relies on endoscopic observation and identification of changes in pattern. Though the molecular mechanism revealing the pathogenesis of stomach cancer has been well investigated, further study is still necessary to search for novel and effective therapeutic strategies. Recently, epidemiological studies have found that patients with Helicobacter Pylori infection or high-nitrate diet intake may be an inducement or co-acting factor for stomach cancer, as its existence increases the risk of processing stomach tumors [3,4]. Gastric carcinoma frequently exhibits rapid progression, a poor response to therapeutic strategies, and high mortality [5]. The pathogenesis of gastric cancer and its associated tumorigenesis has not been fully understood, but genetic, immunological, and environmental factors are regarded as critical positions [5,6].

Increasing reports have indicated that inflammatory cytokines and chemokines can result in upregulated oxidative stress through the inactivation of antioxidative stress signaling and activation of inflammatory signaling pathways, including the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Nrf2/Keap1) axis, signal transducer and activator of transcription family (STATs), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), signal transducer and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs), synergistically promoting cancer cell survival and tumorigenesis progression [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Nrf2, a key regulator of oxidative stress, is considered the main regulator that governs cellular homeostasis during oxidative stress. During homeostasis conditions, Nrf2 activity is principally regulated by the redox sensor protein Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). The anti-inflammatory effects of most electrophilic Nrf2 activators are partly Nrf2-independent and include inhibition of other inflammatory mediators, such as the innate immune kinase interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) [11,12]. Besides, KEAP1 serves as a sensor for endogenous and exogenous electrophiles and oxidants due to it containing several highly reactive cysteine residues that, upon chemical modification, prevent its ability to target NRF2 for degradation, leading to NRF2 accumulation and upregulation of a large network of cytoprotective proteins. Both NRF2 and KEAP1 can undergo post-translational modifications and interact with other proteins that affect their functions. Thus, in addition to NRF2, KEAP1 has multiple other binding partners, which in turn have roles in a plethora of cellular processes.

Abnormal Nrf2 signaling was continuously observed in a series of tumors, including gastric cancer, which was involved in carcinogenesis and carcinogenic ogression. Moreover, previous reports also demonstrated that the persistent NRF2 activation by agonist or transgene-mediated Nrf2 overexpression can significantly increase metastasis and proliferation of tumor cells [[12], [13], [14]]. Nevertheless, the regulatory functions of immune factors and Nrf2 signaling, particularly their corresponding underlying molecular mechanisms, are not fully understood. In particular, recent reports with different degrees of evidence have found that the risk of gastric cancer is markedly correlated with the Nrf2 signaling pathway 15, 16. Interestingly, during the progression of tumorigenesis, an increase in Nrf2 abundance in the cytoplasm significantly suppressed the degradation of Nrf2 itself, followed by an acceleration of Nrf2 trafficking and nuclear translocation. These findings also further illustrate that under different physiological pathological conditions, Nrf2 may have a variety of different posttranslation modifications that synergistically or antagonistically determine its protein fate.

Among a series of forms of protein chemical modifications, palmitoylation exhibits a decisive role in regulating a series of functional proteins. Posttranslational S-palmitoylation catches C16 fatty acid palmitate (PA) to the cysteine (Cys) residues of the anchored protein and governs distinct functions of targeted proteins under various pathological and physiological conditions [17,18]. Importantly, palmitoylation has been determined to govern the targeted protein localization and trafficking. This biological process is dependent on catalysis by an acyltransferase family known as Zinc finger-aspartate-histidine-histidine-cysteine (DHHC)-CRD (cysteine rich domain)-type palmitoyl acyltransferases. However, it is largely unknown whether palmitoylation participates in posttranslational modification of Nrf2 and the effects on Nrf2 function.

In this work, we uncovered that Nrf2 is posttranslationally S-palmitoylated at the C514 residue by the DHHC2 palmitoyltransferase, which promotes its stabilization and nuclear translocation. Gastric carcinoma with high levels of DHHC2 promoted palmitoylated Nrf2 abundance, and this modification blocked Nrf2 ubiquitin-proteasome-related degradation via the removal of ubiquitination chains, thus increasing gastric carcinoma growth and decreasing ROS levels. Destabilisation of the palmitoylation of Nrf2 by DHHC2 deficiency in gastric tumor cells or by 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP), a general suppressor of protein S-palmitoylation, retarded gastric carcinoma growth via destabilisation of Nrf2 signaling, thus also indicating a potential and promising therapeutic strategy for the therapeutic management of stomach carcinoma. More importantly, in light of the anti-cancer effect of 2-BP on stomach cancer, we constructed biomimetic cytomembrane-coating GNP nanoparticles with 2-BP and an OXA dual-drug delivery system. In response to near-infrared (NIR) laser irradiation, an in situ photothermolysis was performed, which subsequently operated hyperpyretic release-related on-demand drugs controlled-release from the CM@GNRs-BO reservoir to conclude a synergistic photothermal/chemotherapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical consent

The entire experimental procedures associating with animals presented in the current study were permitted by the Guide for the Care & Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition NIH, in Chinese) and permitted by the Institutional Animal Use & Care Committee (IACUC) in Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (Jinan, China). The approaches associated with this work were used in line with the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Administration of Experimental Animals (Revised & Exposure Draft), issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (http://www.most.gov.cn).

Regarding human subjects investigated with this study, the patients with gastric carcinoma (GC) phenotypes were recruited from the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery and Clinical Trial Research Center at Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (Jinan, China). The diagnosis of GC was based on radiologic, clinical, and endoscopic examinations and histologic records. The detailed characteristics are described in Supplemental Table 1. All patients donors provided informed consent, and the research was permitted by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (Jinan, China).

2.2. Cells lines and cell culture

Human gastric carcinoma (GC) NCI–N87 (Cat#: CRL-5822), KATO III (Cat#: HTB-103), SNU-1 (Cat#: CRL-5971), Hs746 T (Cat#: HTB-135), MKN-45 (Cat#: ABC-TC0687, AcceGen™), SNU-5 (Cat#: CRL-5973), OCUM-1 (Cat#: CVCL_3084, Cellosaurus) cell lines, and human gastric epithelial GES-1 (Cat#: CVCL_ EQ22, Cellosaurus) cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), AcceGen™ or Cellosaurus. The whole cell lines were verified to be free of Mycoplasma. GC cell lines were cultured in the RPMI1640 culture medium (Cat#: 350-000-CL, Wisent, Canada) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum-Premium quality (FBS, Cat#: 085–150, Wisent, Canada), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Cat#: KGY0023, KeyGEN Bio TECH, China) in culture plates in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. The normal GES-1 cell line was cultivated in RPMI1640 medium containing 10 % FBS and 1 × penicillin-streptomycin solution (Cat#: 10,378,016, Gibco, Shanghai, China) according to the product and instruction manuals.

2.3. Antibodies, chemicals and reagents

Primary antibodies presented in the work and against the following indicated targeting proteins were purchased from Abcam Inc®, Shanghai, China: anti-ACTIN (Cat#: ab179467, 1/2500 ratio dilution), anti–HO–1 (Cat#: ab52947, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-NQO1 (Cat#: ab80588, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-ubiquitin (linkage-specific K48) (Cat#: ab140601, 1/200–1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Ub (Cat#: ab134953, 1/200–1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Lamin B1 (Cat#: ab229025, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Bcl-2 (Cat#: ab182858, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Bax (Cat#: ab32503, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Caspase-3 (Cat#: ab184787, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 (Cat#: ab32042, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-Cleaved PARP (Cat#: ab32064, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-MMP14 (Cat#: ab51074, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti–NF–κB p65 (Cat#: ab32536, 1/1000 ratio dilution) and anti–NF–κB p65 (phospho S536) (Cat#: ab76302, 1/1000 ratio dilution). The anti-ZDHHC2 (Cat#: LS-B15757-50, 1/200–1/1000 ratio dilution) was obtained from LifeSpan BioSciences (Beijing, China). The anti-Nrf2 (Cat#: 12,721, 1/1000 ratio dilution), anti-HA (Cat#: 3724, 1/250–1/1000 ratio dilution) and anti-Flag (Cat#: 14,793, 1/250–1/1000 ratio dilution) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology™ (CST) (Shanghai, China). The additional anti-Na, K-ATPase (Cat#: H00000483–B01P, 1/1000 ratio dilution) were purchased from Novus Biologicals, LLC (Shanghai, China).

The Novagen™ BCA protein quantification kits (Cat#: 712,853, MilliporeSigma, Beijing, China) was used to determine samples’ protein concentration. The HRP-tagged secondary antibodies (Cat#: 33201ES60, Yeasen, Beijing, China) with 1/10,000–1/15,000 ratio dilution was used for visualization in western blotting analysis. The MG132 (Cat#: HY-13259), cycloheximide (Cat#: HY-12320), dimethylsulfoxide (Cat#: HY-Y0320), ABD957 (Cat#: HY-142161), 3-methyladenine (Cat#: HY-19312), bortezomib (Cat#: HY-10227) and chloroquine (Cat#: HY-17589 A) were purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE), Shanghai, China. Biotin picolyl azide (Cat#: 900,912), alkynyl myristic acid (Alk 14) (Cat#: 1164), alkynyl palmitic acid (Alk 16) (Cat#: 1165), and alkynyl stearic acid (Alk 18) (Cat#: 1166) were obtained from Click Chemistry Tools. The alkynyl arachidic acid (Alk 20) were synthesized and produced in our lab (>98 % purity). The 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) (Cat#: 21,604), palmostatin B (Palm B) (Cat#: 178,501), NH4Cl (Cat#: A9434) and BSA (Cat#: V900933) were obtained from Merck KGaA. The palmostatin M (Palm M) (Cat#: 565,407) was purchased from MedKoo Biosciences, Inc (Morrisville, NC, USA). TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (Cat#: P/N4304437) and PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green (Cat#: A25742) were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Shanghai, China).

The specific antibody for pan palmitoylation detection was produced according to previous study and patent (CN106153941) [41]. Briefly, to produce antibody targeting pan palmitoylation, a short peptide with only 2 Cys C–C (pal) (98.5 %), in which one cysteine was palmitoylated, synthesized and used as the hapten according to previous protocols and procedures [42]. Meanwhile, the obtained peptide C–C (pal) was conjugated with keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH) as the carrier to immunise New Zealand white rabbits. Ammonium sulfate precipitation was used to purify this anti-serum before use. To better verify this antibody, we have used several additional verification strategies. In brief, according to the thioester bonds between the protein and palmityls, free sulfhydryl groups can be produced by the hydroxylamine buffer liquid. Thiopropylsepharose 6 B (TS-6B) resin was used to purified the hydroxylamine buffer-incubated palmitoylated valosin-bearing protein, followed by immunoblotting assay with anti-valosin-bearing protein antibody. On the other hand, the obtained antibody was further used to observe the small c-terminal domain phosphatase 1 (SCP1) palmitoylation, as described in a previous study [43]. Additionally, in this work, this antibody was subjected to observe the palmitoylated proteins collected from cells treated with different compounds, such as Palm B, Palm M or 2-BP. All the above protocols synergistically supported the sensitivity and specificity of the antibody to the proteins palmitoylation reaction.

The hyaluronic acid (HA) with thiol modification (Cat#: GS220F) were purchased from Advanced BioMatrix. The gold nanorods (GNRs) (Cat: 900,367) with average 25 nm diameter were obtained from Sigma. Also, the OXA (Cat: HY-17371) was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE) (Shanghai, China).

2.4. Knockout and knockdown cell lines preparation

The ready-made system for knockout cell lines construction in the indicated targeted gene-deficiency was founded as described previously [44,45]. In brief, the stomach cancer NCI–N87 cell line with ZDHHC1-ZDHHC24 knockout was prepared by clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats-CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) system. The ready-made small guide RNA (sgRNA) for human ZDHHCs gene was established and cloned into pLentiCRISPRV2 vectors (Cat#: P14402, Miaoling Bio, China) to create the CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA-packaging lentivirus. Small guide RNA (sgRNA) for establishment of knockout THLE2 cells was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., as described in Supplementary Table 2. Oligonucleotides for the sgRNAs were packaged into pLentiCRISPRV2 vectors digested with BsmBI restriction enzyme. The obtained clones bearing gene deletion were isolated and recognized by western blotting.

2.5. Vectors establishment and cells transfection

The empty vector pcDNA3.1 was purchased from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). The human NRF2 gene, mutated NRF2 (m) gene and DHHC2 gene were cloned into empty pcDNA3.1 to generate pcDNA3.1-NRF2-EGFP-HA, pcDNA3.1-NRF2-EGFP-Flag, pcDNA3.1-NRF2 (m)-EGFP-HA, pcDNA3.1-NRF2 (m)-EGFP-Flag, respectively. Additionally, to exogenously overexpress DHHC2, full-length Homo sapiens DHHC2 cDNA plasmids were established by PCR-based cDNA amplification, followed by packing into the pcDNA™ 3.2 3 × Flag-tagged plasmids and the pcDNA™ 3.2 3 × HA-tagged plasmid (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Shanghai, China), respectively. Abridged DHHC2 and Nrf2 tiny fragments expression vectors including Flag-DHHC2 WT, Flag-DHHC2 △TMD1&2, Flag-DHHC2 △DHHC-CRD, Flag-DHHC2 △TMD3&4, HA-Nrf2 WT, HA-Nrf2 △Neh1, HA-Nrf2 △Neh3, 6 and HA-Nrf2 △Neh2, 4, 5, 7 were accordingly prepared.

The Myc-tag bearing ubiquitination vectors were constructed and packaged into pcDNA™ 3.2 plasmid. Vectors were subsequently transfected into NCI–N87 cells using DOTAP Eukaryotic Cell Transfection Reagent (Cat#: C1510, APPLYGEN, Beijing, China) in accordance with the operating manual. Furthermore, to explore the functional effects of DHHC2 in vitro, adenovirus-loading targeted protein expression vectors were established using a ready-made adenovirus packaging kit (Haixing Biosciences, Suzhou, China). The full-length Homo sapiens DHHC2 cDNA plasmids and corresponding ready-made shRNA targeting human DHHC2 (shDHHC2), human WT DHHC2 sequences with C154A mutant, and Homo sapiens full-length Nrf2 and USP15 sequences were respectively packaged into adenovirus using ready-made adenovirus packaging kit (Haixing Biosciences, Suzhou, China). The obtained adenovirus particles were accordingly purified and titrated to 6.5 × 1010 PFU via Adenovirus Purification Mini Kit (Cat#: V1160-01, Shanghai Juncheng Biotechnology, China) in accordance with the operating manual. For the transfection progress, indicated cells were plated in 6-well, 12-well, or 24-well plates with 60 % fusion for 24 h before cell transfection, then transfected with KeygenTrans™ Transfection Reagent (Cat#: KGD031, KeyGEN Bio TECH, China) according to the product description. In brief, the transfection mixture was prepared with 2 μg vector, 5 μl Lipo 3000 transfection reagent, and 120 μl Gibco Opti-MEM™ (Shanghai, China).

2.6. Histological analysis

To perform histopathologic investigations, cells or tissues were fixed with a 10 % neutral formaldehyde solution (Cat#: C1040410015, Nanjing Chemical Reagent, China) and then sectioned transversely. The cell slices were treated with the indicated primary antibodies at 4 °C for 24 h. Histological images were captured by a research-level ortho-optical biological microscope (Cat#: WMS-3590, WUMO, Shanghai, China) for specimen section investigation and a confocal laser microscopy system (Cat#: FV3000, Olympus, Japan) for immunofluorescence section investigation after corresponding secondary antibody incubation. The 10 % neutral formaldehyde solution fixed tumor specimens for 24 h and were then implanted in an O·C.T (optimal cutting temperature) compound. Embedded tissues were sectioned into 20-μm slices. For IHC staining, the paraffin slices were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated, followed by blocking in 5 % normal goal serum/3 % BSA (Beyotime, Hangzhou, China) for 1.5 h. Indicated primary antibodies were added for incubation overnight at 4 °C. After washing, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:300 dilutions; Abcam) was added for 1 h of incubation. DAB substrate (Beyotime, Hangzhou, China) was added to examine the signals. Images were captured under a light microscope (Olympus).

2.7. Co-immunoprecipitation

For the co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) analysis, the indicated cell lysates were prepared and treated with the antibodies at 4 °C for 24 h and BeaverBeads™ Protein A/G (Cat#: 22,202–100, Beaverbio, Suzhou, China). After washing the beads for three times, the indicated obtained immunoprecipitates were suspended in 1 × sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) Loading Buffer (Cat#: CW0027S, HangZhou Nuoyang Biotechnology, China). The eluates from the IP beads were collected for further analysis using immunoblotting.

2.8. In vivo and In vitro interaction ubiquitination assay

The in vivo or in vitro interaction ubiquitination assay were respectively performed in accordance with the previously described methods [44,45]. Briefly, the in vivo ubiquitination assay was performed as follows: cells were lysed in SDS lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1 % SDS) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche), and denatured by heating for 5 min. The supernatants were diluted 10-fold with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1 % Triton X-100) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche, Shanghai, China). After centrifugation at 20,000 r.p.m. for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies.

2.9. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay

The cells or tissues RNA were collected and separated by TRNzol Universal agentia (Cat: DP424, TIANGEN®, Beijing, China) in accordance with the operating manual. The ready-made RNA samples were kept at −80 °C Ultra-low temperature freezer (Cat#: BDW-86L770, BEING, Shanghai, China) for no more than 10 days. The RNA purity was determined by the 260/280 nm adsorption ratio (values > 2.00). Next, 1.5 μg of purified RNA was used for reverse transcription using a universal RT-PCR kit. (Cat#: RP1100, Solarbio Life Sciences, Beijing, China) and qPCR reaction premix Mix (Cat#: CB94843831, ChemicalBook, Beijing). The inverse transcription procedure was carried out at 42 °C for 1 h, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70 °C for 10 min. The PCR process was carried out using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green (#A25742, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and SensiMix SYBR Master Mix Kits (#QP100001, OriGene Technologies, Wuxi, China) in ABI PRISM 7900 H T systems (Applied Biosystems, Shanghai, China). The specific primer sequences were established by Tsingke Bio (Beijing, China) or ready-made primers were obtained from OriGene Technologies, Inc.

2.10. Western blotting detection

For the western blotting assay, samples were homogenized into ready-made samples for western blotting analysis using the Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer solution (Cat#: CW2333S, 3-Biologic Quantity Technology Service, Shanghai, China). Then, the final homogenates extraction were concentrated via centrifugalization at 4 °C, 13,000 rpm for 30 min. The corresponding collected protein samples were analyzed for concentration using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat#: YSD-500 T, Yoche-Biotech, Shanghai, China), with lipid-free BSA as control. Cell lysates were subjected to 10%–12 % SurePAGE™ ready-made gel kit (Cat#: M00664 & M00667, Genscript, Nanjing, China) and then transferred to a 0.45 μM polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Cat#: WJ002, Epizyme Biotech, Shanghai, China), together with immunoblotting using the indicated primary antibodies. Next, the PVDF membranes were treated with Q-BLOCK western blocking buffer solution (Mine-bio, Shanghai, China) in 1 × TBS working buffer solution (Cat: PH1402, Scientific Phygene®) containing 0.1 % Tween-20 (Cat: 9005-64-5, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China) (1 × TBST working buffer solution) for 1 h, and incubated with the assigned primary antibodies at 4 °C for 24 h. Western blotting PVDF membranes were exposed using hypersensitive chemiluminescence (ECL) kit assay (Cat#: ES-0006, FineTest®, Wuhan, China) to AGFA Structurix Rollpac X-ray film (Cat#: AGFA D4, Shandong, China). Indicated protein contents were then measured as gray value levels (V4.6.6, Quantity One, The Discovery Series, Bio-Rad, USA) and normalized to ACTIN or GAPDH.

2.11. Labelling, click chemistry, palmitoylation identification and streptavidin pulldown

With this experiment and procedures, the Click-iT™ Palmitic Acid (PA), Azide Kit (Cat#: C10265), Click-iT™ Protein Reaction Buffer Kit (Cat#: C10276) and Click-iT™ Cell Reaction Buffer Kit (Cat#: C10269) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and then used to perform click chemistry and identification of palmitoylated Nrf2 according to product instruction. After the indicated transfection of Nrf2 WT and Nrf2 C514S mutant, cells were incubated with 100 μm Click-iT PA, azide and maintained in a 5 % CO2, 37 °C condition for 6 h. After 6 h treatment, the cells were harvested and washed for 3 times with iced PBS (Cat#: 72,013,560, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China), followed by mixture with lysis buffer (Cat#: YB25-05097) containing 1 × protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (EDTA free) (Cat#: HY-K0013, MedChemExpress, China). The lysates were maintained at 4 °C for 30 min, then lysates were transferred to 1.5 mL trace centrifugal tube. The final cell lysates were concentrated by centrifugation at 4 °C, 15,000 rpm for 5 min. Protein concentration of collected supernatant was confirmed by EZQ™ Protein Quantitation Kit (Cat#: R33200, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with product manuals. The total extracted protein was then incubated with biotin-alkyne using Click-iT™ Protein Reaction Buffer Kit. Then, the corresponding biotin-alkyne-palmitic acid, azide-protein complexes were processed to streptavidin-mediated pulldown assays via Pierce™ Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (Cat#: 88,817, Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by western blotting analysis with Nrf2 antibody.

In addition, to further identify palmitoylation of Nrf2, a complementary method was also used in this section. The cells also were incubated and lysed with 1 % Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 % SDS, 50 mM TEA-HCl, pH 7.4 buffer containing 1 × protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (EDTA free), accompanied by click reaction with biotin azide. Cellular proteins were harvested using 10 vol of 100 % methyl alcohol at −80 °C for 2 h, and then re-harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 13 min. The precipitates were re-suspended in 100 mL 1 × sample suspension buffer and then diluted to 10-fold immunoprecipitation solution containing 0.5 % Nonidet P 40, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA and solution with pH 7.4. Labeled cellular proteins were enriched by streptavidin agarose at 25 °C with gentle vortex for 2–3 h. Protein-bound streptavidin agarose (SA) beads were washed three times with immunoprecipitation solution and bound proteins were eluted with elution buffer (95 % formamide and 10 mM EDTA with pH 8.2) at 95 °C for 10 min. Samples were subsequently subjected to immunoblotting detection.

2.12. Fractionation assay

Fractionation of samples was performed using the Subcellular Protein Fractionation Kit (Cat#: NBP2-47659, Novus Biologicals, Shanghai, China). The nuclear component was lysed with homogenization solution (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM triethanolamine, 4 % SDS, 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail, 2 mM PMSF, 1500 units/ml benzonase nuclease, pH 7.3). EDTA was added to a final lysates of 5 mM after solution removal. The cytoplasmic component was diluted with homogenization solution containing 5 mM EDTA before fractionation assay.

2.13. Cell proliferation assay

The CCK-8 method was used to evaluate the proliferation of cancer cells. Cells were grown in a 96-well plate (2 × 103 cells/well) for different time points. After each treatment, the culture supernatant was removed, and 10 μl Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was added to each well (Cat#: HY-K0301, MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China). After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, a microplate reader was used to examine the absorption value at 450 nm. Colony formation was also used for cell proliferation analysis. Briefly, the cancer cells were plated in 24-well plates with 200 cells in each. After 2 weeks, colonies with more than 50 cells were imaged and counted after crystal violet staining. The EdU staining was also used to calculate cell proliferation. Cells were also cultivated in a 96-well plates with 2 × 104 cells per well. A Cell-Light EdU Apollo 567 In Vitro Kit (Cat#: C10310-1, RIBOBIO, Guangzhou, China) was used to evaluate cell proliferation.

2.14. Transwell detection

Cell migration and invasion were measured using Transwell analysis. The transwell insert (Cat#: CLS3412, Corning®, Transwell®, USA) was incubated with Matrigel (Cat#: 356,234, BD, USA). Indicated tumor cells were re-cultured in Ultra-CULTURE serum-free medium (Cat#: 12–725 F, LONZA, USA), and plated in the upper chamber (5.5 × 104 cells per well). Next, the medium containing 10 % FBS was placed to the lower chamber, followed by incubation for 48 h. Then, cells in the upper chamber were completely removed using a cotton swab. Cells migrating into the lower chamber were rinsed, fixed with 10 % neutral formalin solution (Cat#: E672001, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and stained using 0.5 % crystal violet. Finally, the cells were imaged with a microscope. The experiment was carried out with identical techniques for the calculation of migration, with the exception that Matrigel was eliminated after the upper chamber was precoated.

2.15. In vivo tumor models construction

1.5 × 106 OCUM-1 or NCI–N87 cells (stable clones made with lentiviruses) suspended in 75 μl PBS were subcutaneously inserted into the flanks of BALB/c mice. When the xenograft tumors reached the expected volume, mice were randomly assigned to one of the therapy groups. Every 2–3 days, the length and width of the tumors were measured with a vernier caliper. The tumor volume was determined using the formula 1/2D (major axis)d2 (minor axis). When tumor sizes reached 2 cm2 or ulceration was noticed, mice were slaughtered without pain. The palmitoylation inhibitor 2-BP (0, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 mg/kg) was administered peritoneally into mice with NCI–N87 tumors on a daily basis.

2.16. Construction of NCI–N87 cytomembrane-coated thiol modified hyaluronic acid-conjugated-gold nanorods (CM@GNRs) for 2-BP and oxaliplatin (OXA) loading (CM@GNRs-BO)

The established protocols and procedures for preparation of CM@GNRs were used in our current work in accordance with previous reports [46,47]. Prior to use, the thiol-HA component was incubated with tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine for the activation of sulfhydryl group. Next, the total of 3 mL, 0.4 mg/mL GNRs solution (dispersion in H2O) was reacted with activated thiol-HA (1 mg/mL, 150 μL) for 6 h to construct corresponding HA-GNRs. Then the obtained HA-GNRs solution was centrifuged with 6700 g at 20 °C for 0.5 h to get rid of uncombined HA-SH, and re-dispersed in distilled deionized water. Subsequently, according to previous studies [47,48], to prepare the GNRs with 2-BP and oxaliplatin (OXA) dual-loading (GNRs-BO), a total of 2 mL, 1 mg/mL HA, and 0.2 mL, 4 mg/L 2-BP, were incubated with the HA-GNRs, and the obtained solution was reacted for 10 h in the dark (1000 rpm). The OXA dispersed in distilled deionized water (350 μL, 0.3 mg/mL) was gently added to the mixture with constant flow pump at a stable speed of 30 μL per min. Next, after stirring with 1000 rpm for 72 h, the corresponding mixture was centrifuged at 6000 g for 20 min at room temperature to purify the GNRs with 2-BP and oxaliplatin (OXA) dual-loading (GNRs-BO), and re-suspended in phosphate buffer. Then, based on previous reports with certain modification [48,49], to prepare the cytomembrane of NCI–N87 cells, this cell line was centrifuged with 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min to harvest pure precipitations and then was re-suspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (containing membrane protein extraction reagent and PMSF) (Cat: M334, Amresco). Following a 15-min incubation in the cold bath, the NCI–N87 cells were mechanically disrupted using a dounce homogenizer for 50 cycles. Next, the obtained mixtures were centrifuged again at 13,000 g for 50 min. The collected NCI–N87 cytomembrane segments were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C for following experiments. Prior to use, in brief, 1 mg segments were re-suspended in PBS and sonicated for 15 s, and then filtrated using 400 nm polycarbonate (PC) membranes (Kenker, USA) at least 5 times to isolate and harvest the corresponding cytomembrane (CM), respectively. After that, the GNRs-BO were incubated with the CM solution to form CM@GNRs-BO particles, following co-filtrating through 400 nm PC membranes at least 5 times. Finally, the remanent components were centrifuged again at 5000 g for 20 min at 4 °C to collect the formula products (CM@GNRs-BO).

2.17. Characterization of nanoparticles and NIR-mediated intracellular on-demand release of 2-BP

NCI–N87 cells were cultured in a 6-well plate at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well for 36 h. A total dosage of 700 μg/mL CM@GNRs-BO in 1 × serum-free media was distributed to cultured cells for 5 h. At the end of incubation with nanoparticles, cells were re-treated with fresh serum-free medium. Cells were then treated with an 808 nm, 1 W/cm2 laser irradiation for 5 min. The fluorescence pictures of cells were captured (Olympus, FV3000) at indicated time points over the course of experiments.

Furthermore, the electron microscopy images of obtained nanoparticles were obtained using TEM (Tecnai G2 20,200 kV TEM (Fei, Electron Optics)). Briefly, a small drop of the sample solution in double distilled water was dried on carbon-coated copper grid for TEM analysis. Additionally, dynamic light scattering (DLS) with LB-550 DLS particle size analyzer (Horiba Scientific, Edison, NJ) was used to determine the average size of nanoparticles collected above. The UV–vis absorption was examined with an UV-2600 spectrophotometer (Japan). Photothermal therapy on cells or mice was carried out with an 808 nm laser (Stone, China). Fluorescence spectra were analyzed with a RF-6000 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Japan).

2.18. Loading capacity of 2-BP and OXA and photothermal performance evaluation in vitro

The obtained CM@GNRs-BO were centrifuged and the supernatant containing free 2-BP and OXA was harvested for further quantification. To quantify the loading efficiency, the lyophilized CM@GNRs-BO component was then weighed. UV–Vis spectrometer and ICP-OES were used to determine the amount of the 2-BP and OXA. The LE/LC of 2-BP and OXA were calculated. Moreover, the product of HA-GNR, GNRs-BO, CM@GNRs-BO with same concentration of gold were added into microcentrifuge tube. All the components were treated with NIR laser (808 nm, 1 W/cm2) for 8 min, followed by infrared imaging at each 30 s. To study the photostability of the resulting materials, CM@GNRs-BO (800 μg/mL) were irradiated with laser (808 nm, 1 W/cm2) for 4 cycles, followed by infrared imaging recording.

2.19. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± SEM (the standard error of the mean) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) was used for graphics and statistical analysis. For comparison between two groups, unpaired Student's t tests were used. A one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The investigators were blinded to the animal genotype and grouping information.

3. Results

3.1. Nrf2 can be palmitoylated, and S-palmitoylated Nrf2 maintains its expression

To explore whether palmitoylated Nrf2 was involved in gastric carcinoma progression, we first detected its expression profiles alterations upon treatment of cells with 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP), a general inhibitor of protein palmitoylation challenge. When human NCI–N87 cells were exposed to 2-BP to downregulate palmitoylated proteins, the levels of Nrf2 protein expression markedly reduced in both dose- (Fig. 1A) and time-dependent manners (Fig. 1B). Inversely, significant upregulation in palmitoylation by palmostatin B (Palm B) or palmostatin M (Palm M), the inhibitor of depalmitoylase enzymes, elevated Nrf2 protein levels in NCI–N87 cells (Fig. 1C and D). Such effects of 2-BP, ABD957, Palm B and Palm M on Nrf2 expression were further evaluated by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 1E). Also, cultured NCI–N87 cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX) treatment confirmed that interdiction of palmitoylation by 2-BP challenge promoted Nrf2 degradation, therefore decreasing its protein abundance, while ABD957, Palm B and Palm M increased Nrf2 expression (Fig. 1F). Considering the effects of 2-BP on reduction of Nrf2 expression, click chemistry assay was employed to visualize the palmitoylated Nrf2 (Fig. 1G). Indeed, marked palmitoylation of Nrf2 was observed by the streptavidin beads-mediated pull down and western blotting analysis. In addition, to study the effects of palmitoylated Nrf2 on oxidative stress in cancer cells, suppression of Nrf2 palmitoylation by increasing doses of 2-BP downregulated mRNA levels profiles of antioxidant-related Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, GCLC and GCLM genes, but upregulated ROS levels in SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells (Supplementary Figs. 1A and B). Similar results were also observed in SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells, where 2-BP administration led to long-term increases in ROS levels and decreases in transcriptional levels of genes associated to antioxidants (Supplementary Figs. 1C and D). On the contrary, SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells treated with inhibitors of depalmitoylase enzymes (Palm B or Palm M) reduced ROS production, accompanied by increase of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, GCLC and GCLM genes mRNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 1E-L). The above results suggested that Nrf2 expression is stabilized by S-palmitoylation, and increased palmitoylation contributed to reduction in ROS production in vitro.

Fig. 1.

Determination of palmitoylated Nrf2 in gastric carcinoma cell.

A, Human NCI–N87 cells were treated with gradually increasing doses of 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) for 24 h, and subjected to immunoblotting detection of Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies (n = 4 per group). B, NCI–N87 cells were treated with 60 μM 2-BP for 0, 6, 12 and 24 h and then subjected to immunoblotting with Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies (n = 4 per group). C, D, NCI–N87 cells were incubated with 0, 3 or 6 μM palmostatin B (Palm B) (C) palmostatin M (Palm M) (D), an inhibitor of depalmitoylase enzymes, for 24 h, and subjected to immunoblotting analysis with Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies (n = 4 per group). E, NCI–N87 cells were treated with 60 μM 2-BP, 1 μM ABD957, 6 μM Palm B/Palm M for 24 h. The fixed cells coverslips were subjected to immunofluorescent staining with Nrf2 (green) and DAPI (blue). The bar graph indicating Nrf2 fluorescence intensity in the indicated group (n = 5 images per group; P < 0.05 vs. Control). Scale bars, 10 μm. F, NCI–N87 cells were pre-incubated with DMSO, 2-BP, ABD957, Palm B or Palm M as a baseline, then treated with cycloheximide (CHX). The collected cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting detection with Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies. The right curve graph showing the relative Nrf2 remaining ratio in the indicated time point and corresponding half-time of Nrf2 protein (n = 4 per group). G, Schematic diagram of the Click-iT assay used for Nrf2 palmitoylation analysis. Cells were incubated with 100 μM Click-iT palmitic acid-Azides for 8 h, and lysates were subjected to Click-iT detection, followed by western blotting analysis with Nrf2 antibody. The right western blotting show the Nrf2 expression in the indicated group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The relevant experiments presented in this part were performed independently at least three times. Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test analysis (E). The P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant difference. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.2. Recognition of the palmitoylation site in Nrf2

Considering the critical role of palmitoylation in the regulation of Nrf2 stabilization, this compelled us to identify the definite palmitoylated site of Nrf2. The predicted position of the palmitoylation site on Nrf2 for Homo sapiens and Mus musculuswas studied with a conjoint analysis of GPS-Palm software (MacOS_20,200,219) (The CUCKOO Workgroup, http://gpspalm.biocuckoo.cn/), and MDD-Palm algorithm (http://csb.cse.yzu.edu.tw/MDDPalm/) [19,20]. Both algorithms coincidentally predicated and provided Top 6 palmitoylation sites for Nrf2 with different confidence intervals and quality scores. Of note, cysteine 514 (C514) of human Nrf2 and cysteine 506 (C506) of mouse Nrf2 in the Neh1 domain were predicted to be the most likely and reliable protein palmitoylation modification sites (Fig. 2A and B). These cysteine residues showed strong conservation in different species (Fig. 2C). The replacement of the C514 residue by serine strictly blocked the palmitoylation of Nrf2, as indicated by the Click-iT chemistry assay (Fig. 2D). The C514S mutant dramatically reduced Nrf2 protein expression profiles (Fig. 2E–G). The Nrf2 with C514S mutant concurrently promoted its degradation during CHX treatment (Fig. 2H), therefore decreasing the levels of the remaining Nrf2 (Fig. 2I), similar to the effect of 2-BP administration. Given the identification of C514 as the key site for Nrf2 palmitoylation, we wonder whether Nrf2 with the C514 mutant affected ROS production in tumor cells. As expected, inconsistent with Nrf2 WT, reduced antioxidant-related Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, GCLC and GCLM genes at mRNA levels, decreased glutathione (GSH) contents, and elevated ROS contents were significantly observed in SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells with Nrf2 C514S overexpression (Supplementary Figs. 2A–D), as determined by qPCR analysis and DCFH-DA staining assay. However, no marked changes in ROS contents were detected in the above-mentioned cells with Nrf2 C325S, Nrf2 C199S, Nrf2 C199S, Nrf2 C242S and Nrf2 C422S overexpression, compared to the Nrf2 WT group (Supplementary Fig. 2E). These results indicated that cysteine 514 is a key site for Nrf2 palmitoylation, and Nrf2 with the C514S mutant lost its ability to reduce ROS production and boost the endogenous antioxidant system in tumor cells.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the palmitoylation site on Nrf2 at evolutionary conserved cysteine residues.

A, B, Predicted position of palmitoylation site on Nrf2 in Homo sapiens (A) and Mus musculus (B) using GPS-Palm software (MacOS_20,200,219) (The CUCKOO Workgroup, http://gpspalm.biocuckoo.cn/), and MDD-Palm algorithm (http://csb.cse.yzu.edu.tw/MDDPalm/). C, Palmitoylation site of Nrf2 with conserved cysteine residues in Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Bos Taurus, Rattus norvegicus, Andrias davidianus and Artibeus jamaiccensis. D, NCI–N87 cells with Nrf2 WT or Nrf2 C514S mutant were incubated with Click-iT palmitic acid-Azides for 8 h, and lysates were subjected to Click-iT detection in accordance with product instruction. The palmitoylated proteins were placed onto the pull-down detection by streptavidin-sepharose bead conjugate, followed by western blotting analysis. The palmitoylation of Nrf2 WT was observed in top gel, lane 5, but not for the Nrf2 C514S in top gel, lane 6 or control groups. E, NCI–N87 cells were induced to overexpress with Nrf2 WT or Nrf2 C514S mutant, respectively. The fixed cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining with Nrf2 (red) and DAPI (blue). F, Nrf2 fluorescence intensity in the indicated group (n = 10 images per group; P < 0.05 vs. WT). Scale bars, 10 μm. G, qPCR analysis showing the Nrf2 mRNA levels in Nrf2 WT or Nrf2 C514S mutant (n = 10 per group; P < 0.05 vs. WT). H, Cells with overexpressing Nrf2 WT or Nrf2 C514S mutant were incubated with CHX in a time-course frame. The collected cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting detection with Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies. I, The curve graph showing the relative half-time of Nrf2 protein at the indicated time point (n = 4 per group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The relevant experiments presented in this part were performed independently at least three times. Significance determined by 2-sided Student's t-test. The P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant difference. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.3. Palmitoylation-stabilized Nrf2 retards its proteasome degradation

Previous reports have indicated that stable overexpression of Nrf2 resulted in enhanced resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents including cisplatin, doxorubicin and etoposide. Inversely, downregulation of the Nrf2-dependent response by overexpression of Keap1 or transient transfection of Nrf2–small interfering RNA (siRNA) rendered cancer cells more susceptible to these drugs [15,16,21,22]. Thus, we suspected that Nrf2 may have a variety of different posttranslation modifications that determine its protein fate over the course of distinct physiological and pathological conditions. Accordingly, with these regards, we investigated the effects of palmitoylated Nrf2 on its ubiquitin-proteasome degradation progression. The enhanced degradation of palmitoylation of Nrf2 with the C514S mutant could be interdicted by the proteasome inhibitors MG132 and bortezomib (Fig. 3A), but not by the lysosomal inhibitors chloroquine, NH4Cl or the autophagy suppressor 3-methyladenine (3-MA). To determine the proteasome-dependent manner, palmitoylation inhibitor 2-BP was used to block the endogenous Nrf2 palmitoylation in NCI–N87 cells (Fig. 3B), and evaluated the functional effects of a series of diverse indicated inhibitors on distinct degradation signals. Coincidentally, decreased stabilization of Nrf2 induced by 2-BP-triggered depalmitoylation could be significantly abolished by MG132 and by bortezomib, but not chloroquine, NH4Cl and 3-MA, suggesting that there may be antagonistic effects between ubiquitination and palmitoylation to regulate the stability of Nrf2. Notably, Nrf2 has been confirmed to be degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome previously, thereby blocking its trafficking to the nucleus [21,22]. To investigate the functional effects of depalmitoylation on Nrf2 nuclear translocation, major elements for proteasome assembly, including PSMD1, PSMD4, PSMD7, PSMA1, and PSMB5 (Fig. 3C) were employed to study their colocalization changes with Nrf2 over the course of depalmitoylation. Indeed, treatment with 2-BP largely promoted the colocalization of Nrf2 with the 26 S proteasome while upregulating its colocalization with the 19 S subunit and 20 S subunit aggregation (Fig. 3D and E), as evidenced by the immunofluorescence assay. Moreover, interruption of palmitoylation in Nrf2 with the C514S mutant markedly increased the colocalization of Nrf2 with the proteasome (Supplementary Figs. 3A and B) in the investigated gastric cancer cell lines. These data suggested that depalmitoylated Nrf2 downregulated its stabilization and accelerated proteasome-related degradation progression.

Fig. 3.

Palmitoylation-stabilized Nrf2 is less subjected to its ubiquitination degradation.

A, The NCI–N87 cells were transfected with Nrf2 or Nrf2 C514S mutant, followed by detection of Nrf2 degradation under CHX treatment, in the presence of proteasome inhibitor (MG132, bortezomib), lysosome inhibitor (chloroquine, NH4Cl) or autophagy inhibitor (3-MA). The right curve graph showing the Nrf2 remaining raction in the indicated time point (n = 4 per group). B, Time-gradient CHX treatment detection showing the effects of 2-BP on Nrf2 degradation in cells with/without different inhibitors. The right curve graph showing the relative Nrf2 remaining level in the indicated time point (n = 4 per group). C, Schematic diagram showing the structure of the 26 S proteasome and corresponding representative markers PSMD1, PSMD4 and PSMD7 for 19 S complex, and PSMA1 and PSMB5 for 20 S complex. D, Statistical data of the colocalization of Nrf2 and PSMD1, PSMD4, PSMD7, PSMA1 and PSMB5 in NCI–N87 cells incubated with DMSO or 2-BP (n = 5 per group; P < 0.05 vs. DMSO group). E, Representative immunofluorescence pictures showing the colocalization of ectopically expressed Nrf2 and specific markers of assembled proteasome, PSMD1& PSMB5 in NCI–N87 cells treated with DMSO or 2-BP. Scale bars, 50 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The relevant experiments presented in this part were performed independently at least three times. Significance determined by 2-sided Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test analysis. The P value less than 0.05 was considered for significant difference.

3.4. Acetyltransferase DHHC2 is required for Nrf2 palmitoylation, and DHHC2 activity is positively correlated with stomach cancer progression in human

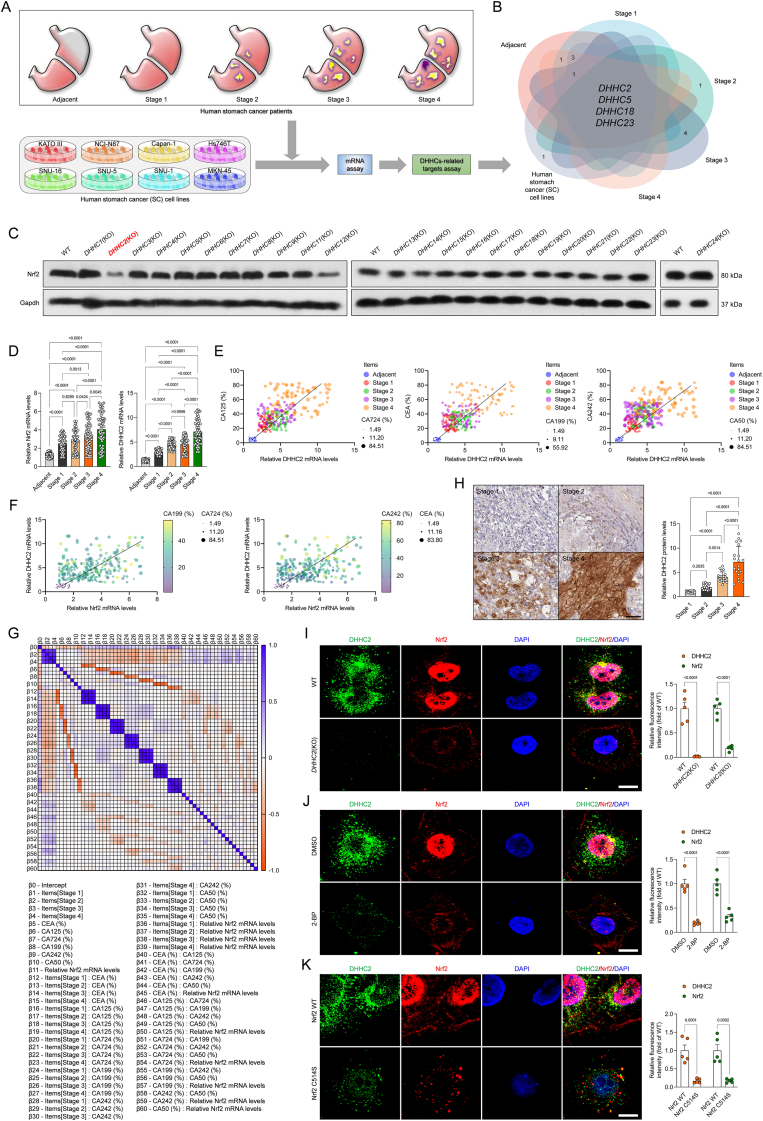

Considering palmitoylation as a key posttranslational modification of Nrf2 in tumor cells, we next inquired which palmitoyltransferase exerts a major role in controlling Nrf2 palmitoylation during stomach cancer progression. To investigate the involvement of DHHC2 in stomach cancer, we detected its levels in tissues obtained from human patients with gastric cancer (stages 1–4) phenotypes and used an in vitro assay (Fig. 4A). Indeed, the analysis of the top 4 distinguishable expressed candidates, including DHHC2, DHHC5, DHHC18, and DHHC23, was highlighted in the intersection of these experiment groups (Fig. 4B). To deeply explore this, human NCI–N87 cells with different DHHCs knockout levels were established, to evaluate Nrf2 protein expression profile changes. Significant reduction in Nrf2 could be observed in DHHC2-deficient cells, but not at the level of other DHHCs members (Fig. 4C). In addition, all the indicators met the selection criteria for the intersection screening, among which Nrf2 and DHHC2 displayed the marked upregulation in the patients with gastric cancer (Fig. 4D). The additional multiple linear regression, pearson multiple correlation analysis and histological analysis further determined the positive correlation of DHHC2 expression with clinic gastric cancer (Fig. 4E–H). Intriguingly, DHHC2 was identified as the major palmitoyltransferase for Nrf2, which did affect Nrf2 stabilization and palmitoylation in DHHC2 deficiency or 2-BP challenge (Fig. 4I and J). Coincidently, invalidation of palmitoylation by C514S decreased the co-expression of Nrf2 and DHHC2 (Fig. 4K). Given the possible tight correlation of DHHC2 with stomach cancer progression, to explore whether DHHC2 expression changes were involved in this process, we then analyzed the correlation of DHHC2 expression with gastric carcinoma (STAD) by bioinformatics analysis. The Oncomine database, PrognoScan database and Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) database confirmed that DHHC2 expression in human patients with STAD phenotype was significantly increased compared with normal controls (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Also, abnormal elevated DHHC2 expression markedly associated with increased tumor immune infiltration, reduced survival rates of patients, and dysfunctional Nrf2 activity (Supplementary Figs. 4B–D). Of note, DHHC2 showed positive expression in clinical stomach cancer samples and weak expression levels in the normal tissues in histological analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4E). Moreover, patients with STAD expressing high DHHC2 showed poorer survival rates than that of the patients with low DHHC2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 4F). Consistently, in our cohort, patients with STAD exhibited strong DHHC2 expression during observation (Supplementary Fig. 4G). qPCR and western blotting assays confirmed that DHHC2 expression at gene and protein levels were remarkably upregulated in tumor samples compared with the paired normal tissue from our cohort (Supplementary Fig. 4H). Additionally, the enrichment score of each immune cell type in STAD was further evaluated, we noted the major infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), which showed a positive relation with DHHC2 expression (Supplementary Figs. 5A and B). Also, the neutrophils' infiltration level had a markedly positive correlation (Spearman R = 0.335, p < 0.001) with DHHC2 expression and was dramatically higher in the DHHC2 high-expression group (Supplementary Figs. 5C and D). We also determined a positive correlation between DHHC2 expression and neutrophils’ markers such as CD44 and CD55 (Supplementary Fig. 5E). The following KEGG assay results indicated that PPAR signaling and growth factor activity terms were markedly enriched (Supplementary Fig. 5F). To further investigate the signaling and pathways influenced by DHHC2, we conducted correlation analysis between DHHC2 and all other mRNAs in STAD using TCGA datasets. The top 29 genes were exhibited in a heatmap as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5G, including Nrf2 and MMP14, which are key molecules involved in inflammatory cell infiltration, cell proliferation and EMT processes. As expected, positive correlations between DHHC2 expression and MyD88, TLR4, RELA (NF-κB p65), TWIST, ZEB1, VEGFA and VEGFB expression were observed in STAD patients (Supplementary Figs. 5H–J). A potential protein interaction between DHHC2 and Nrf2 was identified by the GENEMANIA online datasets (Supplementary Fig. 5K). The qPCR and western blotting assays thereafter confirmed that DHHC2 knockdown significantly decreased Nrf2 and MMP14 gene and protein expression levels in SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells (Supplementary Figs. 5L and M). These findings demonstrated that DHHC2 upregulation might be associated with STAD progression via regulation of cell proliferation and the EMT process.

Fig. 4.

Nrf2 is palmitoylated by palmitoyltransferase DHHC2.

A, Experimental design showing the procedure of identifying ZDHHCs-related targets in different human stomach cancer cell lines, and stomach cancer patients samples (Stage 1-Stage 4), and corresponding adjacent samples. B, Venn diagram showing the Top 4 DHHC candidates of each treatment groups. C, Representative western blotting bands showing the Nrf2 expression changes in different DHHCs-deficient NCI–N87 cells (n = 4 per group). D, Human patients Nrf2 and DHHC2 mRNA expression levels (n = 60 samples for Adjacent; n = 71 samples for Stage 1; n = 71 samples for Stage 2; n = 71 samples for Stage 3; n = 71 samples for Stage 4; P < 0.05 vs. Adjacent). E-G, Pearson multiple correlation analysis for human subjects (E, F), and parameter covariance: multiple linear regression analysis (G) for the indicated parameter indexes. H, Representative immunohistochemical images of DHHC2 expression in clinic tissue of human donors with gastric carcinoma (200 × , n = 20 samples). I, Representative immunofluorescence images of Nrf2 and DHHC2 coexpression in NCI–N87 cells with WT and DHHC2(KO) phenotype, and corresponding fluorescence density analysis J, NCI–N87 cells were incubated with DMSO and 2-BP, followed by immunofluorescence analysis using Nrf2 and DHHC2 antibodies (n = 5 samples per group; P < 0.05 vs. DMSO). Scale bars, 50 μm. K, The NCI–N87 cells with Nrf2 WT or Nrf2 C514S mutant transfection were incubated with Nrf2 and DHHC2 antibodies, and fixed sections were then subjected to immunofluorescence analysis (n = 5 samples per group; P < 0.05 vs. WT). Scale bars, 50 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The relevant experiments presented in this part were performed independently at least three times. Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test analysis or 2-sided Student's t-test. The P value less than 0.05 was considered for significant difference.

3.5. DHHC2-mediated S-palmitoylation of Nrf2 promotes its nuclear translocation

Having the DHHC2 as the major palmitoyltransferase for Nrf2, we next investigated the effects of DHHC2 on Nrf2 nuclear translocation. Also, ectopically expressed DHHC2 in different stomach cancer cell lines elevated Nrf2 protein expression and accelerated its cellular nuclear translocation (Fig. 5D and E). Considering the interaction between DHHCs and their substrates, we inquired whether DHHC2 interact with Nrf2 in tumor cells. Indeed, Co-IP studies indicated that direct binding between DHHC2 and Nrf2 could be remarkably observed in ectopic expression of DHHC2 in human NCI–N87 cells (Fig. 5F). In addition, given the determination of C514 as the key site for Nrf2 palmitoylation, we wonder whether C16-catched S-palmitoylation primarily contributed to chemical modification for Nrf2. Thus, a series of alkyl-labeled fatty acylation including alk-C14, alk-C16, alk-C18 and alk-C20 were used to study this biological process. The Nrf2 can be marked effectively by palmitoylation (with alk-C16) labels, but much less-efficiently marked by labels with alk-C14 chain lengths, stearoylation (alk-C18) or alk-C20 (Fig. 5G and H), this indicating that C16-catched S-palmitoylation are the main acyl groups for Nrf2 chemical modification. Having the C514S mutation as the key site of Nrf2 palmitoylation, we next examined functional effects of these mutants on C16-catched S-palmitoylation over the course of alkynyl palmitic acid (alk-C16) treatment. As expected, Nrf2 with human C514S mutation significantly abolished palmitoylation (with alk-C16) labels, as supported by streptavidin pull-down analysis, which further revealed that human C514S was required for S-palmitoylation of Nrf2 protein (Fig. 5I). Moreover, to further visualize Nrf2 palmitoylation in the presence of DHHC2, similar to the above protocol, we used the alk-C16 as a metabolic sign to examine the effects of DHHC2 on palmitoylated Nrf2 and its nucleus translocation. Incubation with NH2OH markedly suppressed palmitoylation levels in Nrf2, indicating that upregulation of palmitoylated Nrf2 mainly occurred on cysteine and was induced by DHHC2 (Fig. 5J). Fractionation analysis in DHHC2 WT or DHHC2-deficient NCI–N87 cells further evidenced that DHHC2-mediated palmitoylation of Nrf2 elevated the component of the modified Nrf2 protein in the cytoplasm and nucleus but not in the membrane components (Fig. 5K). The above findings consistently indicated that DHHC2 as a major palmitoyltransferase involved in occurrence of palmitoylated Nrf2, and its activity was positively correlated with stomach cancer progression.

Fig. 5.

DHHC2-mediated S-palmitoylated Nrf2 promotes its nucleus localization.

A, Nrf2 and DHHC2 expression tested in the indicated cells transfected with AdshDHHC2 (n = 4 samples per group). B, Representative immunofluorescence images showing the DHHC2 and Nrf2 co-expression in AdshDHHC2-transfected NCI–N87 cells and corresponding fluorescence density Pearson's analysis (n = 5 samples per group; P < 0.05 vs. AdshRNA). Scale bars, 50 μm. C, Palmitoylation levels and Nrf2 expression in NCI–N87 with/without AdshDHHC2 transfection (n = 4 samples per group). D, Nrf2 overexpressing the HA-tagged DHHC2 construct in different cell lines, following western blotting analysis with Nrf2, Gapdh and HA antibodies (n = 4 samples per group). E, Representative immunofluorescence images showing the DHHC2 and Nrf2 co-expression in DHHC2 overexpressing vector-transfected NCI–N87 cells and corresponding fluorescence density Pearson's analysis (n = 5 samples per group; P < 0.05 vs. empty vector). Scale bars, 50 μm. F, NCI–N87 cells were co-transfected with Nrf2 and HA-DHHC2 and subjected to IP of HA. Mutual Co-IP of Nrf2 and DHHC2 indicating binding between endogenous Nrf2 and DHHC2 in NCI–N87 cells. G, Detection of Nrf2 S-palmitoylation in the indicated cells using different alkyl-labeled fatty acylation including alk-C14, alk-C16, alk-C18 and alk-C20. Acylated Nrf2 were detected by streptavidin bead pulldown, followed by immunoblotting assay with Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies (n = 6 samples per group). H, The same protocol similar with (G) was used to detect acylated Nrf2 in NKN-45, Hs746 T and SNU-5 cells. The lysates were then subjected to western blotting analysis with Nrf2 and Gapdh antibodies (n = 6 samples per group). I, Palmitoylation levels of Flag-labeled Nrf2 WT, Nrf2 C514S, Nrf2 C325S, Nrf2 C119S, Nrf2 C199S and Nrf2 C242S mutants were analyzed by labelling with alk-C16 via CLICK reaction-associated streptavidin pulldown. The corresponding lysates were subjected to immunoblotting assay with Flag and Gapdh antibodies (n = 3 samples per group). J, The NCI–N87 cells were transfected with Nrf2-Flag and DHHC2-HA vectors. (Upper) Palmitoylated Nrf2 levels were exhibited using alk-C16 labelling in the presence or absence of NH2OH treatment. (Down) Representative immunofluorescence images showing the HO-1 and Nrf2 co-expression in indicated WT or DHHC2(KO) cells and corresponding fluorescence density Pearson's analysis (n = 5 samples per group; P < 0.05 vs. empty vector). Scale bars, 50 μm. K, The wild-type NCI–N87 cells or DHHC2(KO) NCI–N87 cells were transfected with Nrf2-Flag, followed by labelling with alk-C16. Subcellular fraction was collected and Nrf2 protein levels were modulated to confirm that there were equal amount of Nrf2 in the wild type and knockout cell component for input. Palmitoylated Nrf2 levels in cell membrane (Mem.), cell cytoplasm (Cyto.) and cell nucleus (Nuc.) component were detected by western blotting analysis.

3.6. Nrf2 is required for DHHC2 targeting function, and palmitoylation-stabilized Nrf2 is less subjected to its ubiquitination degradation

Given the role of DHHC2 in regulating the Nrf2 signal, the above obtained in vivo and in vitro results compelled us to study another critical issue, whether and how DHHC2 directly interacted with Nrf2 in vitro. In line with prime binding analysis in Fig. 5F, following Co-IP assay indicated that exogenously expressed DHHC2 did interact with Nrf2 and vice versa, in transfected SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells (Fig. 6A and B). Interaction analysis also showed that the DHHC-CRD domain of DHHC2 was essential for binding to Nrf2. The Co-IP analysis with corresponding DHHC2 mutants further revealed that DHHC2 without the DHHC-CRD domain has no ability to interact with Nrf2. Thus, the DHHC-CRD domain of DHHC2 contributed to protein interaction with Nrf2 (Fig. 6C and D). Also, the inhibition of Nrf2 palmitoylation by 2-BP or DHHC2 deletion resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of HO-1 and NQO1 (critical targets of Nrf2) protein abundance (Fig. 6E and F). These results revealed that depalmitoylation of Nrf2 could affect downstream signaling events of the Nrf2 transcriptional activity. Notably, palmitoylation has been shown to coordinate targeted proteins stabilization by obstructing ubiquitination-related degradation [23]. Thus, we inquired whether ubiquitination of Nrf2 could be interrupted by DHHC2-mediated palmitoylation, followed by antioxidant-associated signaling activation. As expected, reduction of palmitoylation by 2-BP dramatically upregulated the ubiquitin of Nrf2 through K48 linkage, and ablation of DHHC2 in NCI–N87 cells led to a similar observation (Fig. 6G). Subsequently, given the important role of DHHC2 in the regulation and catalysis of palmitoylation, we screened amino acid sequences of the DHHC domain of DHHC2 in various species and underlined a very conserved site in DHHC2 (C154). Indeed, in NCI–N87 cells, DHHC2 with C154A mutant did lose its catalytic function in the suppression of K48-linked Nrf2 ubiquitination and Nrf2 signaling activation (Fig. 6H–K, Supplementary Figs. 6A–D), and this process of ubiquitination was also significantly downregulated by AdshUsp15 (deubiquitinating enzyme 15) (Fig. 6L and M). The above results did reveal that the C154 site in the DHHC domain of DHHC2 is required for its biological catalytic function and modulation of Nrf2 palmitoylation.

Fig. 6.

Palmitoylation-stabilized Nrf2 suppresses its own ubiquitination-proteasome degradation.

A, Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay of Nrf2 and DHHC2 interaction. B, Representative immunofluorescence images of DHHC2 and Nrf2 coexpression in NCI–N87 and SNU-1 cells. (n = 5 samples per group; P < 0.05 vs. WT group). Scale bars, 50 μm. C, D, Schematic of human full-length and truncated DHHC2 and Nrf2 (C), and representative western blots indicating the interaction domains of DHHC2 and Nrf2 (D). E-G, IP detection in NCI–N87 cells showing the effects of the palmitoylation inhibitor 2-BP and DHHC2 deficiency on the binding between Nrf2 and other proteins with known function (E), representative immunofluorescence images of HO-1 and NQO1 coexpression (F), and K48-linked ubiquitination of Nrf2 (G) (n = 5 images per group). Scale bars, 10 μm. H, DHHC2 structure showing the catalytic activity motif mutant (C154A) of the DHHC domain in different species. I, J, IP detection in NCI–N87 cells showing the effects of DHHC2 knockout and DHHC2 with the C154A mutant on the binding between Nrf2 and Nrf2 downstream signaling molecules, i.e., HO-1 and NQO1, representative immunofluorescence images of HO-1 and NQO1 coexpression (right) (I), and K48-linked ubiquitination of Nrf2 (J) (n = 5 images per group). Scale bars, 10 μm. K-M, Immunoblots showing the involvement of Usp 15 in the depalmitoylation-triggered proteasome degradation of Nrf2 in DHHC2-deficient NCI–N87 cells (K) or DHHC2 (C154A)-transfected NCI–N87 cells (L) (n = 4 samples per group). NCI–N87 cells expressing Nrf2 or Nrf2-Ub were transfected with AdshUsp15, followed by incubation of a specific antibody for Nrf2 used to detect the Nrf2 or Nrf2-Ub expression (M). Negative control (NC) or empty vector (EV) were used as control. This experiment was repeated three times.

Having the positive correlation of DHHC2-Nrf2 axis with gastric carcinoma development, we further explored the effects of DHHC2-Nrf2 signaling on tumor cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro. Indeed, the Nrf2 expression was significantly restrained in shDHHC2-transfected SNU-5 and OCUM-1 cells, as validated by qPCR and immunoblotting (Supplementary Figs. 7A and B). The additional CCK-8 and colony formation assays confirmed that DHHC2 knockdown significantly restrained the proliferative capacity of stomach cancer cell lines compared with the shControl group (Supplementary Figs. 7C–E). The transwell analysis demonstrated that DHHC2 silencing markedly decreased the invasion and migration of tumor cells, compared to the corresponding control group (Supplementary Figs. 7F and G). As expected, EMT-related markers including Vimentin, N-cadherin, ZEB1 and MMP2 were strongly decreased in SNU-5 and OCUM-1 cells, while E-cadherin expression was highly elevated (Supplementary Fig. 7H). Moreover, in vivo experiments confirmed that DHHC2 suppression efficiently reduced the tumor growth rates and tumor weights in the established mice bearing OCUM-1 tumor model (Supplementary Figs. 7I and J). These results verified that DHHC2 absence contributed to the suppression of gastric cancer cell proliferation and EMT process. Additionally, immunoblotting results indicated that Nrf2-related signaling including HO-1, NQO-1 and p–NF–κB protein expression levels were obviously reduced in SNU-5 and OCUM-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 8A). To further study the potential role of Nrf2 in DHHC2-mediated gastric carcinoma progression, DHHC2 was then overexpressed in cells, and empty vector served as a control. The qPCR and western blotting results verified the alterations of Nrf2 mRNA levels in DHHC2-overexpressing tumor cell lines (Supplementary Figs. 8B and C). Furthermore, we found that promoting Nrf2 stabilization not only accelerated cancer cell proliferation, but also significantly abrogated the anti-proliferative capacity of shDHHC2, as indicated by the restored cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 8D). Similarly, DHHC2 overexpression enhanced SNU-5 and OCUM-1 cells migratory and invasive properties. Meanwhile, DHHC2 knockdown-reduced migration and invasion of tumor cells were strongly abrogated upon Nrf2 overexpression (Supplementary Figs. 8E–G). Similarly, N-cadherin, Vimentin, ZEB1 and MMP2 gene expression levels were increased in SNU-5 and OCUM-1 cells with Nrf2 overexpression, while E-cadherin was restrained. Importantly, DHHC2 knockdown-mediated expression of these genes was remarkably abrogated in these Nrf2-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 8H). These results demonstrated that Nrf2 is required for DHHC2 targeting function in suppression of stomach cancer progression.

3.7. Interruption of Nrf2 palmitoylation by 2-BP inhibits tumor growth in mice

Since depalmitoylation exhibited important effects on Nrf2 expression and nuclear translocation, we inquired whether suppression of DHHC2 or the 2-BP treatment, was capable of restraining tumor cell survival and tumor growth in mice model. In this regard, NCI–N87 and SNU-1 cells were incubated with 2-BP or Palm B. Indeed, suppression of palmitoylation via 2-BP largely reduced Nrf2 binding and increased Caspase-3 binding in tumor cells, while the binding of Nrf2 and Caspase-3 processes were reversed by inhibitor of depalmitoylase Palm B (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Similar findings were also found in the apoptotic cell raction of SNU-1 and NCI–N87 cells and apoptosis-associated indicators including Bcl2, Bax, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP expression during 2-BP or Palm B treatment (Supplementary Figs. 9B and C). In addition, by knocking down DHHC2, overexpression of Nrf2 WT and corresponding Nrf2 C514S led to similar protein levels in apoptosis-related indicators. This suggested that DHHC2 primarily controlled C514, which was a significant site of Nrf2 palmitoylation (Supplementary Fig. 9D). To further evaluate the requirement of palmitoylation for Nrf2 function in vivo, the lentivirus-mediated shRNA targeting DHHC2 was used to knockdown DHHC2 in mice bearing NCI–N87 cells-triggered tumorigenesis, and enclosed a rescue treatment with overexpression of Nrf2. As expected, mice with shDHHC2 treatment significantly retarded NCI–N87 tumor growth, while increase of Nrf2 expression largely rescued tumor growth (Supplementary Figs. 9E–G). These findings collectively revealed that targeting DHHC2-mediated Nrf2 palmitoylation conferred protection against tumor growth in the NCI–N87 tumor model.

Given the pharmacological activity of 2-BP in the suppression of DHHC2-Nrf2-related tumor growth in vivo, we investigated various different concentration of 2-BP (0, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 and 20.0 mg/kg) in the NCI–N87 tumor model. Mice treated with the above-mentioned doses of 2-BP exhibited a dose-dependent pharmacological effect on inhibition of mice bearing NCI–N87 tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. 9H). Coincidentally, the increasing doses of 2-BP also markedly elevated the infiltration of CD8+ cells in tumor samples (Supplementary Fig. 9I-L). In addition, the NCI–N87 with Nrf2 deletion cell line was established. Then, similar to the above method the adenovirus-mediated overexpressing vectors targeting Nrf2 WT (AdNrf2 (WT)) and Nrf2 C514S (AdNrf2 (C514S)) were used in mice bearing NCI–N87 (Nrf2−/−) cells-triggered tumorigenesis. The adenovirus-mediated empty vector was treated as a control (AdControl). As expected, consistent with our other findings, mice with AdNrf2 (C514S) treatment significantly retarded tumor growth, while an increase in AdNrf2 (WT) administration largely promoted tumor growth. Indeed, the Nrf2 with C514S mutant loses its ability to support oncogenesis in mouse model-bearing xenografts (Supplementary Fig. 9M − P). These above results confirmed that C514 is a key site of Nrf2 palmitoylation and played a critical role in tumor growth in the NCI–N87 tumor model. Targeting DHHC3-mediated palmitoylation of Nrf2-promoted antitumor immunity in the tumor model and targeting Nrf2 palmitoylation by 2-BP can efficiently suppress Nrf2-dependent immune evasion of tumor cells and tumor growth.

3.8. Establishment and characterization of a novel biomimetic nano-reservoir delivery system

Given the anti-tumor effect of 2-BP on tumor cells proliferation in vitro and tumor growth in vivo, we designed a novel biomimetic nano-reservoir delivery system based on gold nanorods (GNRs), which was packaged with a stomach cancer cell cytomembrane for cooperative cancer photothermal and chemotherapy (Fig. 7A). The GNRs with hyaluronic acid (HA) modification were used in this section as nanocarriers. The 2-BP was first added by electrostatic interaction, followed by incubation with OXA via a chelation reaction, and the GNPs were finally packaged into a stable OXA cross-linked 2-BP-loaded nano-reservoir (GNRs-BO). Subsequently, these nanoparticles were then coated with a cytomembrane harvested from NCI–N87 cells (CM@GNRs-BO), which was highly expressing CD74. Membrane proteins, especially CD74, play a key role in isotypic interactions between NCI–N87 cells. Due to the dual stabilizing effect of HA-modified nano-carriers and cancer cell cytomembrane, the delivery system significantly prolongates blood circulation and avoids premature release. The unique capacity of cytomembrane-coated nanoparticles to specifically target homologous cells, together with the synergistic effects of photothermal therapy and chemotherapy using gold nanorods and 2-BP-OXA, results in the outstanding efficacy of CM@GNRs-BO in vivo against cancers. The ultraviolet visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy exhibited two characteristic peaks including the longitudinal surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peak at 660 nm and transverse surface plasmon resonance peak at 510 nm, indicating the successful fabrication of rod-shaped nanocarriers (Fig. 7B). Then, OXA was subjected to these nanoparticles as a physical crosslinker to form OXA and a 2-BP dual drug-loading GNRs (GNRs-BO) mixture based on the chelation of OXA with the side carboxyl groups from HA. The nanocarriers were finally packaged with cytomembrane vesicles (CM) isolated from stomach cancer cell line NCI–N87 via ultrasonication and physical co-extrusion (CM@GNRs-BO). The LSPR peak of the obtained nanoparticles was red-shifted to about 670 nm, probably due to the altered molecular conformation after packaging with cytomembrane or drugs. Of note, the characteristic peaks of 2-BP were detected in CM@GNRs-BO, suggesting the integrity of the designed dual drug-loading nanocarriers after physical co-extrusion (Fig. 7B). The dual drug-packaging abundance and loading content of CM@GNRs-BO were 10.1 % and 52.8 % for 2-BP, and 4.7 % and 61.2 % for OXA, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Characterization of CM@GNRs-BO drug delivery system.

A, Schematic graph of the formulation of biomimetic 2-BP and OXA dual drug-load GNRs and their bio-function for synergistic chemotherapy and homotypic targeted photothermal therapy for cancer cells. B, Ultraviolet visible spectra of GNR, GNRs-BO, CM@GNRs-BO and 2-BP (upper); and fluorescence spectra of GNR, CM@GNRs-BO and 2-BP (lower) with the excitation wavelength of 490 nm. C, D, Nanoparticles size intensity (C) and zeta potentials (D) of the GNR, GNRs-BO, CM@GNRs-BO and CM vesicles examined by DLS. E, Temperature curve of HA-GNR, GNRs-BO, CM@GNRs-BO and PBS under 808 nm laser irradiation (1 W/cm2) (left), and corresponding photo-stability of CM@GNRs-BO in response to laser irradiation. F–H, TEM images of HA-GNR (F), GNRs-BO (G) and CM@GNRs-BO (H). I,In vitro cellular uptakes of GNR, GNRs-BO, CM@GNRs-BO and PBS.

Next, dynamic light scatterer (DLS) and zeta potential analysis were used to determine the size of GNR, GNRs-BO, CM@GNRs-BO and corresponding cytomembrane (CM) vesicles. In Fig. 7C and D, the prepared CM@GNRs-BO nanoparticles (93.5 ± 6.7 nm) displayed a larger particle size than those detected for pure GNRs (61.2 ± 3.3 nm), which indicated that the HA component of about 31 nm thickness was packaged into the GNRs. Also, after determination of structure, the photothermal properties were then examined with a real-time infrared thermal camera. The temperature of nanoparticles containing HA-GNRs, GNRs-BO, and CM@GNRs-BO significantly increased above 55 °C under laser irradiation for 500 s (808 nm, 1 W/cm2) while the temperature of PBS only elevated about 3 °C (Fig. 7E), suggesting that nanoparticles and cell membrane packaging did not influence the photostability. In addition, to evaluate the photostability, 4 cycles of 808 nm laser irradiation were delivered to CM@GNRs-BO nanoparticles, which all exhibited consistent and similar photothermal conversion (Fig. 7E). Notably, the results further showed that the thickness of the nanocarriers was relatively close to the lifting size of GNRs-BO, indicating 2-BP, OXA, HA and GNRs were loaded into a consolidated system. The TEM images of CM@GNRs-BO also conferred visual data that a core (GNRs-BO)-shell (cytomembrane) structure was constructed with a cell membrane thickness of about 5 nm (Fig. 7F–H). Treated cells with CM@GNRs-BO nanoparticles incorporated in vitro more nanoparticles than cells treated with GNR- or GNRs-BO in vitro experiments. Meanwhile, the markedly decreased cell viability could be attributed to CM@GNRs-BO uptaken by the different gastric cancer cell lines, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 10A and B.

3.9. Treatment with CM@GNRs-BO performs a synergistic photothermal and chemical therapy in suppression of gastric cancer cell growth