Abstract

Neuroinflammation is crucial in the onset and progression of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease (PD). We aimed to determine whether 3-N-Butylphthalide (NBP) can protect against PD by inhibiting the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway and the inflammatory response of microglia. MitoSOX/MitoTracker/Hoechst staining was used to detect the levels of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) in BV2 cells. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction was used to measure the levels of free cytoplasmic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in BV2 cells and mouse brain tissues. Behavioral impairments were assessed using rotarod, T-maze, and balance beam tests. Dopaminergic neurons and microglia were observed using immunohistochemical staining. Expression levels of cGAS, STING, nuclear factor kappa-B (NfκB), phospho- NfκB (p-NfκB), inhibitor of NfκBα (IκBα), and phospho-IκBα (p-IκBα) proteins in the substantia nigra and striatum were detected using Western Blot. NBP decreased mitochondrial ROS levels in rotenone-treated BV2 cells. NBP alleviated behavioral impairments and protected against rotenone-induced microgliosis and damage to dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and striatum of rotenone-induced PD mice. NBP decreased rotenone-induced mtDNA leakage and mitigated neuroinflammation by inhibiting cGAS-STING pathway activation. NBP exhibited a protective effect in rotenone-induced PD models by significantly inhibiting the cGAS-STING pathway. Moreover, NBP can alleviate neuroinflammation, and is a potential therapeutic drug for alleviating clinical symptoms and delaying the progression of PD. This study provided insights for the potential role of NBP in PD therapy, potentially mitigating neurodegeneration, and consequently improving the quality of life and lifespan of patients with PD. The limitations are that we have not confirmed the exact mechanism by which NBP decreases mtDNA leakage, and this study was unable to observe the actual clinical therapeutic effect, so further cohort studies are required for validation.

Keywords: neuroinflammation, microglia, 3-N-butylphthalide, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes pathway, Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder worldwide. It affects approximately 1% of individuals >50 years and 2%–3% of those over 65 years. 1 The clinical symptoms of PD are divided into: (1) motor symptoms, including bradykinesia, rigidity, postural instability, and static tremor, 2 and (2) non-motor symptoms, including anxiety, depression, constipation, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. 3 PD has two crucial pathological features: the formation of Lewy bodies and the loss of dopaminergic neurons. 4 Mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and autophagy abnormalities are the core mechanisms underlying PD.5,6 The effect of neuroinflammation on PD is garnering increasing attention. 7 Microglia are essential for neuroinflammation. In 1988, researchers found numerous activated microglia around neurons in the substantia nigra of patients with PD. 8 Microglia are sensitive to various stimuli such as toxins, and can be activated to secrete large amounts of inflammatory factors. Many inflammatory factors released by microglia have neurotoxic effects, especially tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). TNF-α can directly bind to its receptors on dopaminergic neurons, subsequently activating caspase-8 and causing neuronal apoptosis. 9 Additionally, rats overexpressing IL-1β are highly sensitive to 6-OHDA (a neurotoxic agent) and consequently exhibit severe dopaminergic neuronal damage. 10 Therefore, inhibiting excessive neuroinflammation and microglial overactivation is a novel approach for PD treatment. 11

Rotenone, a classical neurotoxin, has unique advantages for modeling PD in vivo and in vitro.12,13 Chronic and persistent exposure to rotenone can produce a consistent PD model that recapitulates many key features of PD pathogenesis and pathology,12,13 especially sporadic PD.13,14 In neurons, rotenone inhibits respiratory chain complex I in the mitochondria and subsequently induces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to progressive damage of dopaminergic neurons.14,15 Pathological changes induced by rotenone are not limited to dopaminergic neuron deterioration,16–18 but also include overactivation of microglia adjacent to the neurons. Sherer et al. revealed that rotenone can activate microglia in rodent PD models before the anatomical pathology results in dopaminergic neurons loss. 19 Additionally, rotenone activates BV2 cells and microglia in mouse brains, producing large amounts of proinflammatory factors.20,21

Butylphthalide (NBP) is beneficial in treating acute ischemic stroke.22,23 Its mechanisms include antioxidation, promoting cerebral blood flow (CBF), and reducing post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI). 24 NBP protected the mitochondrial function in PD neuronal cell models.25–27 NBP can ameliorate mitochondrial impairment induced by 6-OHDA in SY5Y cell models. 25 Huang et al. showed that NBP inhibited ROS production and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) reduction in a PD model of PC12 cells.26,27 However, the signaling mechanisms underlying the protective effects of NBP remain unclear.

The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway is part of the innate immune system. cGAS detects self or foreign DNA in the cytoplasm and is subsequently activated, forming cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) and activating STING. 28 STING subsequently activates nuclear factor kappa-B (NfκB) and type I interferon pathways, resulting in an inflammatory cascade releasing various proinflammatory mediators. 29 Moreover, cGAS-STING pathway is associated with neuroinflammation and is a potential prospective treatment for PD. 30 Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) leakage induced by oxidative stress activates the cGAS-STING pathway. 31 In Parkin-deficient mice, cell-free circulating mtDNA increases, indicating that mtDNA leakage occurs during PD. 32 A meta-analysis indicated increased STING levels in the substantia nigra of patients with PD, suggesting that cGAS-STING signaling is related to PD pathogenesis. 31 In the brain, the STING protein is mainly expressed in the microglia.33,34 However, whether activation of the cGAS-STING pathway can promote neuroinflammation and accelerate PD progression remains uncertain.

In this study, we aimed to explore whether NBP could attenuate microglia-induced neuroinflammation by inhibiting the cGAS-STING pathway in vivo and in vitro PD models. We used MitoSOX/MitoTracker staining to detect mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) levels in BV2 cells and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) to detect free cytoplasmic mtDNA levels in BV2 cells and mouse brain tissues. Moreover, dopaminergic neurons and microglia were observed by immunohistochemical staining. In addition, expression levels of cGAS, STING, NfκB, phospho-NfκB (p-NfκB), inhibitor of NfκBα(IκBα), and phospho-IκBα (p-IκBα) proteins in BV2 cells and brain tissues were detected using Western Blot. As PD is an irreversible progressive degenerative disease, drugs such as levodopa provide temporary relief from symptoms and their abilities to hinder progression or prevent the disease remain limited. Therefore, an effective therapy that can modify the disease and delay its progression is urgently required. Previous studies have primarily focused on the therapeutic effects of NBP in cerebrovascular diseases. Whether NBP can be applied to neurodegenerative diseases needs to be further confirmed. The molecular mechanism by which NBP alleviates neuroinflammation and the dopaminergic neuron loss remains unclear. However, our study revealed a new molecular mechanism underlying the effective role of NBP in mitigating neuroinflammation and protecting dopaminergic neurons in PD, providing a theoretical foundation for the application of NBP in PD therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

BV2 microglial cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, United States). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s high glucose medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA). Subsequently, 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P1400, Solarbio, China) were added to the DMEM. The cells were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37°C in an incubator.

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old, 20–25 g) were acquired from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). All animals were maintained in a temperature-controlled room (23°C–25°C) with 12 h light and 12 h dark and were allowed free access to food and water. All attempts were made to reduce pain and discomfort experienced by the animals. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Shandong University (Animal ethical approval number: DWLL-2023-134).

Experimental design

For the in vitro experiments, when the cells have grown to a density of 70%–80%, NBP (generously provided by Shijiazhuang Pharmaceutical Group, NBP Pharma Co., Ltd, China) or C-176 (GC33823, GLPBIO, USA) were diluted to 100 µMol/L (for NBP) or 10 µMol/L (for C-176) and incubated with the cells for 24 h. Rotenone (R8875, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) was diluted to 0.25 µMol/L incubated for 24 h.

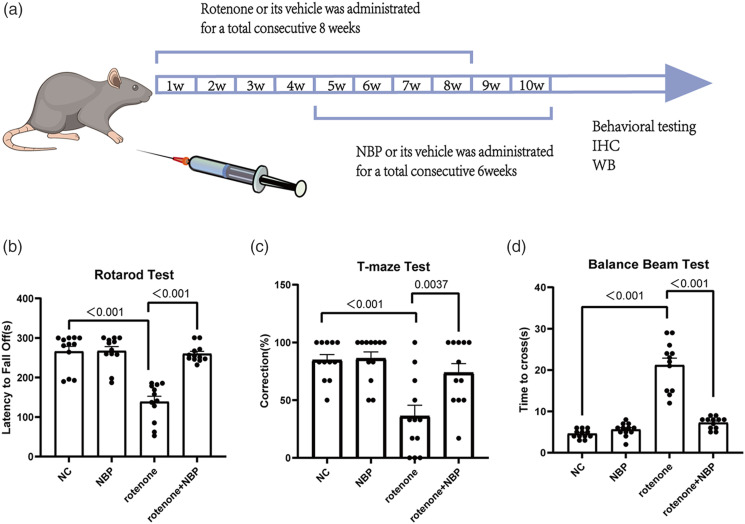

Four groups were assigned for the in vivo studies: (1) control, (2) NBP, (3) rotenone, and (4) NBP + rotenone. Male mice were randomly selected (n = 12 mice per group). Rotenone was administered intragastrically for 8 consecutive weeks (from the first week to the eighth week) (Figure 4(a)). NBP (200 mg/kg/day) was administered intraperitoneally for 6 weeks (from the fifth and tenth weeks) (Figure 4(a)). Simultaneously, an equal volume of saline was administered to the mice in the control group.

Figure 4.

NBP alleviates the behavioral impairments in rotenone-induced PD mice. (a) Design of the study and scheme about drug administration. (b) Latency to fall off in the rotarod test. (c) Correct rate in the T-maze test. (d) Time to cross the balance beam. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 12). p value is provided in all histograms.

Cell viability assay

A cell counting kit (CCK)-8 assay (A311-02; Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used to assess cell viability. Briefly, cells were cultured in 96-well plates (5 ×104 cells/well). Subsequently, the cells were incubated in an NBP solution (10 µMol/L, 50 µMol/L or 100 µMol/L) for 24 h and then exposed to 0.25 µM/L rotenone for 24 h. Finally, 10 µL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and cultured for another 4 h at 37°C. Finally, the cell viability was measured at an absorbance of 450 nm using a multimode microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Detection of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

ROS levels in the mitochondria of BV2 cells were determined using MitoSOX (M36008, Invitrogen) staining, and the morphology of BV2 cells was elucidated using MitoTracker staining (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States). Briefly, BV2 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and subjected to various treatments. Living cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5 µMol/L MitoSOX for 15 min and 20 nMol/L MitoTracker Green FM for 40 min at 37°C in the dark. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Hoechst 33342 (C0031; Solarbio) was added for 10 min. Finally, samples were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX73, Tokyo, Japan).

Rotarod test

A rotarod treadmill (ZH300 B, Zhenghua, China) was used to assess motor coordination. Before the formal test, adaptive training was performed for 3 days until none of the mice fell within 5 min. When the mice were tested, the speed was slowly increased from 4 rpm to 40 rpm over 5 min. If the mouse fell off or clung to the rod for two consecutive turns without walking, the trial was terminated. The time required for the mouse to remain on the rod was recorded.35–38

Balance beam test

This apparatus consisted of 1 m beams and a 2 cm wide surface. At the end of the beam, a black box with nesting material was placed as the finish point. The animals underwent 3 days of training to traverse the length of the beam before testing. When the mice were tested, the time taken to cross the beam was recorded.36,39,40

T-maze test

Spatial working memory was detected using T-maze tests. 41 On days 1–3, the animals were handled for 15 min each day to reduce stress effects during the experiments,42,43 and were subjected to mild food deprivation. On days 4 and 5, the animals could freely explore the maze for 15 min using the available food reward pellets. The animals were trained on days 6–8. The animals were forced to enter one arm of the maze to obtain a food reward and were confined there for 10 s while the other arm was blocked by a sliding door. Subsequently, the blocked door was removed. The animals were placed again in the initial arm and allowed to freely choose either arm. If they entered a previously unvisited arm, they were rewarded. Six trials were performed each day at 10 min intervals. On the test day, the number of corrections made when the animals entered the unvisited arm of the T-maze was measured and the accuracy was calculated.42,44

Total protein extraction and western blot analysis

For the in vitro experiments, cells were obtained and lysed. For the in vivo experiments, fresh mouse brain tissues from the substantia nigra and striatum were collected and lysed. Then the supernatant was collected using centrifugation (4°C; 13,000 g; 20 min), and a Bicinchoninic Acid protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was used to measure the protein concentrations. Loading buffer (Solarbio, China) was used to dilute protein samples and the protein was boiled for 10 min at 100°C.

Furthermore, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels were used to separate soluble proteins (40 µg). Subsequently, the separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon Transfer Membrane, Millipore, USA) using an electrical condition of 110 V for 70 min. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. On the second day, secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were added for 1 h. We used an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States) to detect the immunoreactive signal, and ImageJ 1.8.0r software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States) for analysis.

The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-β-actin (1:5000, BE3212-100, EASYBIO, Seoul, South Korea), anti-tyrosine hydrolase (TH; 1:1000, 25859-1-AP, Proteintech, China), anti-cGAS (1:1000, 26416-1-AP, Proteintech, China), anti-STING (1:1000, 19851-1-AP, Proteintech, China), anti-NfκB (1:1000, 8242S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States), anti-p-NfκB (1:1000, 3033S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States), anti-IκBα (1:1000, AF5002, Affinity, China), anti-p-IκBα (1:1000, 2859S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States), and anti-GAPDH (1:5000,GB15004, Servicebio, China).

The secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit and anti-mouse (1:5000; ZB-2301, ZSGB-BIO, China).

RNA isolation and quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

TRIzol (Invitrogen, 15596-026) was used to extract total RNA, and a cDNA Synthesis kit (Vazyme, R323-01) was used to convert 1 µg RNA to cDNA by reverse transcription. Subsequently, we performed qRT-PCR and calculated the relative mRNA levels quantified by the 2−ΔΔCT method;

The primer sequences were listed:

| Name | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | 5′CCCTACAGTGCTGTGGGTTT3′ | 5′GAGACATGCAAGGAGTGCAA3′ |

| 16S rRNA | 5′AAGTTTAACGGCCGCGGTAT3′ | 5’AGTTGGACCCTCGTTTAGCC’3’ |

Cytosolic mtDNA quantification and total DNA extraction

To measure the mtDNA levels in the cytosol, every cell or tissue sample was separated into two equal parts. In one part, a mitochondrial isolation kit (PH1592, PHYGENE, China) was used to obtain the mitochondria-free cytosol. Total cytosolic DNA was extracted using a DNA Extractor kit (DP304, TIANGEN, China), and the short regions of the 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) genes were amplified to obtain mtDNA. Subsequently, the whole genome DNA of the other sample parts was extracted using the DNA Extractor kit and β-actin genes were amplified to determine nuclear DNA (nDNA). To determine cytosolic mtDNA levels, we calculated the mtDNA/nDNA ratio;

The primer sequences were listed:

| Name | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 5′TGTCTCCTGCGACTTCAACA3′ | 5′GGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACT3′ |

| cGAS | 5′CCAATCTAAGACGAGAGCCGT3′ | 5′GCCAGGTCTCTCCTTGAAAACTAT3′ |

| STING | 5′CCAGCCTGATGATCCTTTGGG3′ | 5′GGCTAGGTGAAGTGCTAGGT3′ |

| IL-1β | 5′GTGTCTTTCCCGTGGACCTT3′ | 5′AATGGGAACGTCACACACCA3′ |

| IL-6 | 5′CTTCTTGGGACTGATGCTGGT3′ | 5′CTCTGTGAAGTCTCCTCTCCG3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′CGGGCAGGTCTACTTTGGAG3′ | 5′ACCCTGAGCCATAATCCCCT3′ |

Immunohistochemistry

The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital, and brain samples were collected and sequentially immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The samples were dehydrated in a 30% sucrose solution and embedded in OCT (Sakura Finetek, United States). We cut the coronal sections (30 µm) serially. Immunohistochemical staining was performed to determine the number of ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule-1 (IBA-1)-positive and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive cells. The sections were observed under a microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

The primary antibodies used were IBA-1 (1:300,10904-1-AP, Proteintech, China) and TH (1:300,25859-1-AP, Proteintech, China). Secondary antibodies were obtained from the kit (PV-9000, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China).

Statistical analysis

We used Graph Pad Prism 9.0 software for statistical analyses, and expressed data as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). We also used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test35,36,45 to analyze the differences between groups. At least three independent experiments were conducted. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

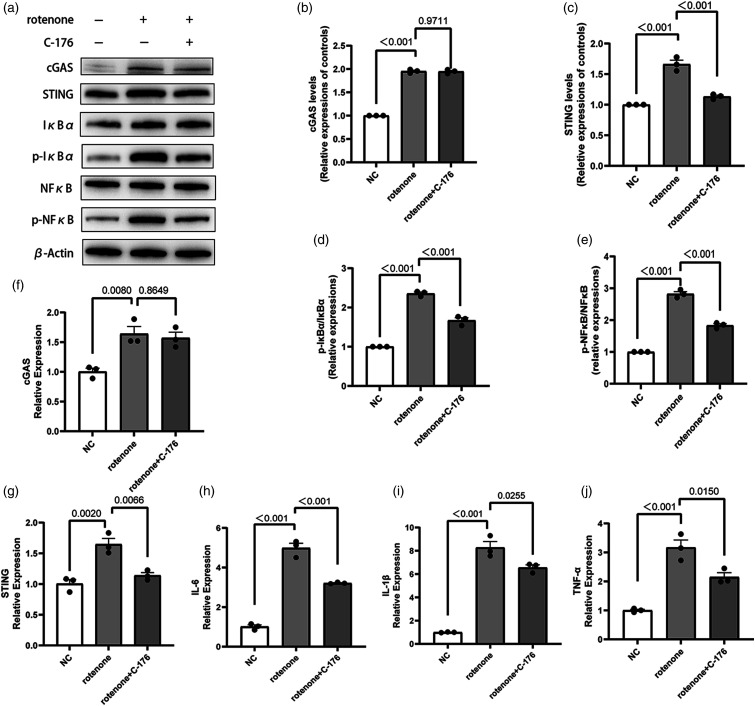

Stimulator of interferon genes inhibitor (C-176) suppresses inflammation in BV2 cells induced by rotenone

To establish a foundation for subsequent experiments, we investigated whether the cGAS-STING pathway was activated in BV2 cells exposed to rotenone. Additionally, we examined whether inhibiting this pathway could reduce the inflammatory reaction induced by rotenone. According to Western Blot and qRT-PCR, the cGAS-STING pathway was upregulated in rotenone-induced BV2 cells, with an increase in the ratios of p-Nfκb/Nfκb, p-IκBα/IκBα and the production of proinflammatory factors including Interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and TNF-α (Figure 1). However, the STING inhibitor C-176 inhibited the activation of STING and simultaneously decreased the ratios of p-NfκB/NfκB, p-IκBα/IκBα and the release of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α (Figure 1). This indicates that the cGAS-STING pathway was upregulated in the rotenone-induced BV2 cell model, leading to BV2 cell activation and the release of proinflammatory factors. Moreover, blocking this pathway can reduce inflammatory responses in BV2 cells. These results demonstrate that rotenone-induced inflammation is related to the cGAS-STING pathway in BV2 cells.

Figure 1.

Effects of the STING inhibitor (C-176) on the inflammatory response of rotenone-induced BV2 cells. (a)-(e) Expression levels of cGAS, STING, NfκB, p-NfκB, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins in BV2 cells were detected using Western Blot. β-Actin was used as the control. (f)-(j) The mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, cGAS, STING in BV2 cells was measured using qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as the control. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 3). p value is provided in all histograms.

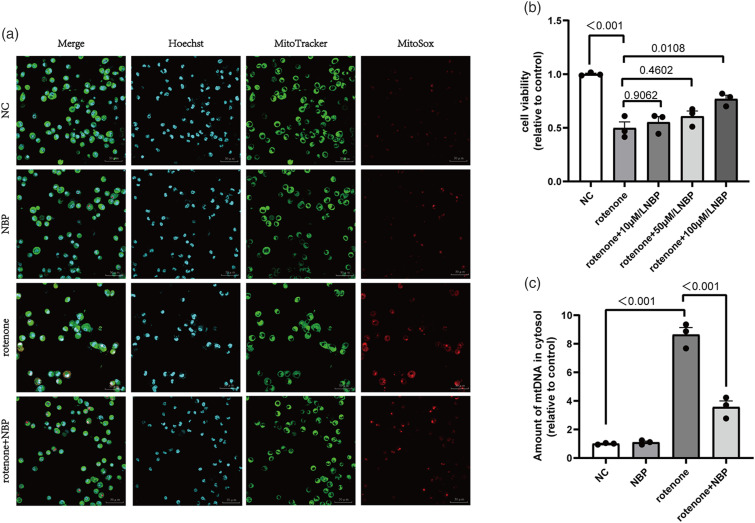

N-Butylphthalide protects BV2 cells from rotenone-induced cell viability injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, and mtDNA leakage

We investigated the effects of NBP on rotenone-induced cell viability and mitochondrial damage in BV2 cells. First, we used the CCK-8 assay to measure cell viability. Compared to the normal control group, rotenone reduced BV2 cell viability by 50% (Figure 2(b)). However, the rotenone + NBP group showed a marked increase in cell viability (Figure 2(b)). Subsequently, we employed MitoTracker and MitoSOX fluorescence staining to determine the localization of mitochondria and the mtROS content. We observed a significant increase in mtROS levels in rotenone-treated BV2 cells, whereas NBP alleviated mtROS production (Figure 2(a)). Furthermore, we used qRT-PCR to measure the amount of mtDNA leakage. The results showed that rotenone caused mtDNA leakage into the cytoplasm, whereas NBP alleviated this leakage (Figure 2(c)). Based on these results, we concluded that NBP can protect BV2 cells from viability injury and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by rotenone and reduce mtROS levels and mtDNA leakage in the cytoplasm.

Figure 2.

NBP inhibits rotenone-induced cell viability injury, mitochondrial ROS levels and mtDNA leakage. (a) MitoSOX (red)/MitoTracker (green)/Hoechst (blue) staining was performed to detect the level of mitochondrial ROS in BV2 cells. (b) Cell viability was measured using a CCK8 assay in BV2 cells. (c) The levels of cytoplasmic free mtDNA in BV2 cells were detected using qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 3). p value is provided in all histograms.

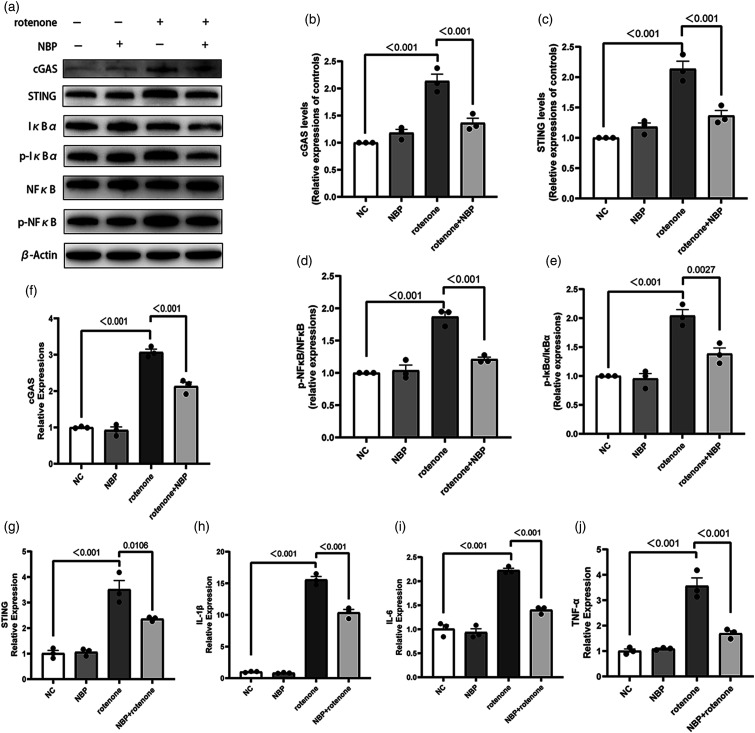

N-Butylphthalide inhibits the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes pathway activation and inflammation induced by rotenone in vitro

We used Western Blot and qRT-PCR to explore the relationship between NBP and the cGAS-STING pathway. We used Western Blot to detect the levels of cGAS, STING, NfκB, p-NfκB, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins. While rotenone increased the levels of cGAS and STING proteins as well as the ratios of p-NfκB/NfκB and p-IκBα/IκBα, NBP alleviated these changes (Figures 3(a)–(e)). qRT-PCR results showed that rotenone increased the mRNA levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in BV2 cells. Compared with the rotenone group, the mRNA levels of these inflammatory factors were reduced in the rotenone + NBP group (Figures 3(f)–(j)). These results suggest that NBP inhibited the upregulation of the cGAS-STING pathway and decreased the ratios of p-NfκB/NfκB, p-IκBα/IκBα, and the production of proinflammatory factors in BV2 cells. These findings suggest a new mechanism by which NBP inhibits neuroinflammation.

Figure 3.

NBP inhibits the activation of the cGAS-STING signaling and inflammation induced by rotenone in BV2 cells. (a)-(e) Western Blot for cGAS, STING, NfκB, p-NfκB, IκBα, and p-IκBα to detect protein levels. β-Actin was used as the control. (f)-(j) mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-a, cGAS, STING in BV2 cells were measured by qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as the control. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 3). p value is provided in all histograms.

N-Butylphthalide alleviates behavioral impairments in mice exposed to rotenone

NBP improves behavioral impairments in mice with symptoms resembling PD when exposed to rotenone. Effects of NBP on motor function and spatial memory have also been observed in mice. Analysis of the rotarod and balance beam tests revealed that mice treated with rotenone showed impaired motor function, evidenced by a reduction in the time spent on the rotarod and increase in the time taken to complete the full-length balance beam (Figures 4(b) and (d)). Compared with rotenone-treated mice, mice subjected to both NBP and rotenone showed improved motor function (Figures 4(b) and (d)). Based on the results of the T-maze test, the rotenone-treated mice showed impaired spatial memory with reduced accuracy in choosing the correct arm (Figure 4(c)). Compared with rotenone-treated mice, mice subjected to both NBP and rotenone showed increased accuracy, suggesting an improvement in spatial memory (Figure 4(c)).

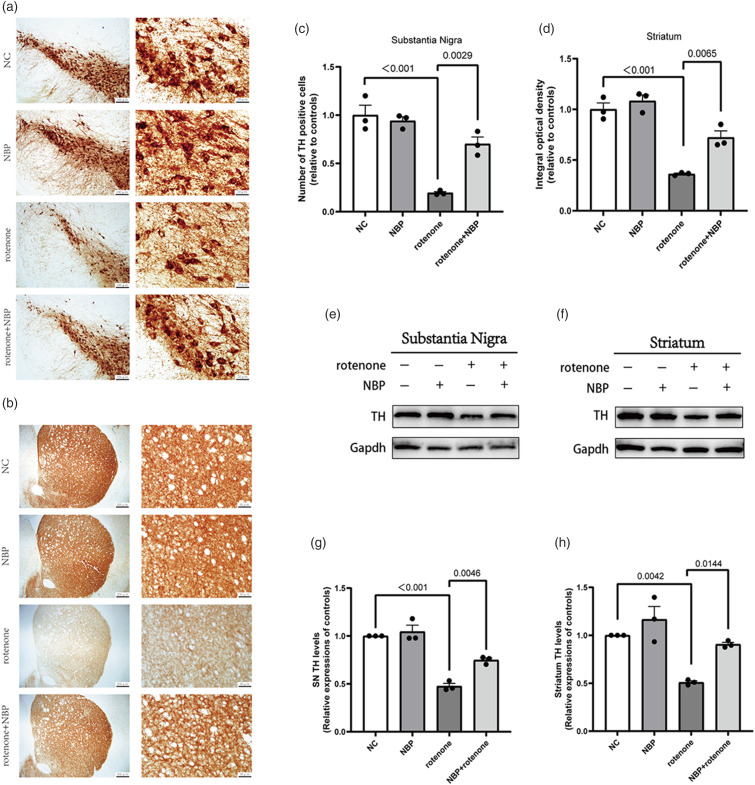

N-Butylphthalide attenuates dopaminergic neuron toxicity and microgliosis in rotenone-induced mice

We used immunohistochemistry to observe the degree of dopaminergic neuron loss, and Western Blot to detect the levels of TH protein in the striatum and substantia nigra. TH immunohistochemical staining revealed that rotenone-treated mice had a significant loss of dopaminergic neurons in the striatum and substantia nigra compared with the control mice (Figure 5(a)–(d)). Compared to the rotenone group, the number of dopaminergic neurons and fibers in the striatum and substantia nigra of the rotenone + NBP group was increased (Figure 5(a)–(d)). The results were further confirmed by assessing TH protein content using Western Blot, which showed that NBP could alleviate the reduction in TH protein expression induced by rotenone in the striatum and substantia nigra (Figure 5(e)–(h)). These results demonstrate that NBP can alleviate dopaminergic neurotoxicity in a PD model.

Figure 5.

NBP protects dopaminergic neurons in rotenone-induced PD mice. (a) Typical immunohistochemical staining showing TH positive cells in the substantia nigra. (b) Typical immunohistochemical staining showing TH positive nerve fibers in the striatum. (c) Numbers of TH positive cells in substantia nigra. (d) The relative optical density of TH staining in striatum. (e)-(h) Western Blot for TH protein levels in tshe striatum and substantia nigra. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 3). p value is provided in all histograms.

Since microglial activation in the brains of PD mice is an important pathological feature, we used IBA-1 immunohistochemical staining to observe microglial activation. We found that IBA-1 positive cells in the striatum and substantia nigra of rotenone-treated mice increased (Figure 6(a)–(d)). Compared to the rotenone group, IBA-1 positive cells in the striatum and substantia nigra of the rotenone + NBP group markedly decreased (Figure 6(a)–(d)). These results demonstrated that NBP inhibited microglial activation in rotenone-induced PD mouse models.

Figure 6.

NBP inhibits microglial activation and mtDNA leakage in the striatum and substantia nigra induced by rotenone. (a)-(b) Immunohistochemical staining showing IBA-1 positive cells in the striatum and substantia nigra. (c)-(d) Numbers of IBA-1 positive cells in substantia nigra and striatum. (e)-(f) The levels of free cytoplasmic mtDNA in the substantia nigra and striatum were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 3). p value is provided in all histograms.

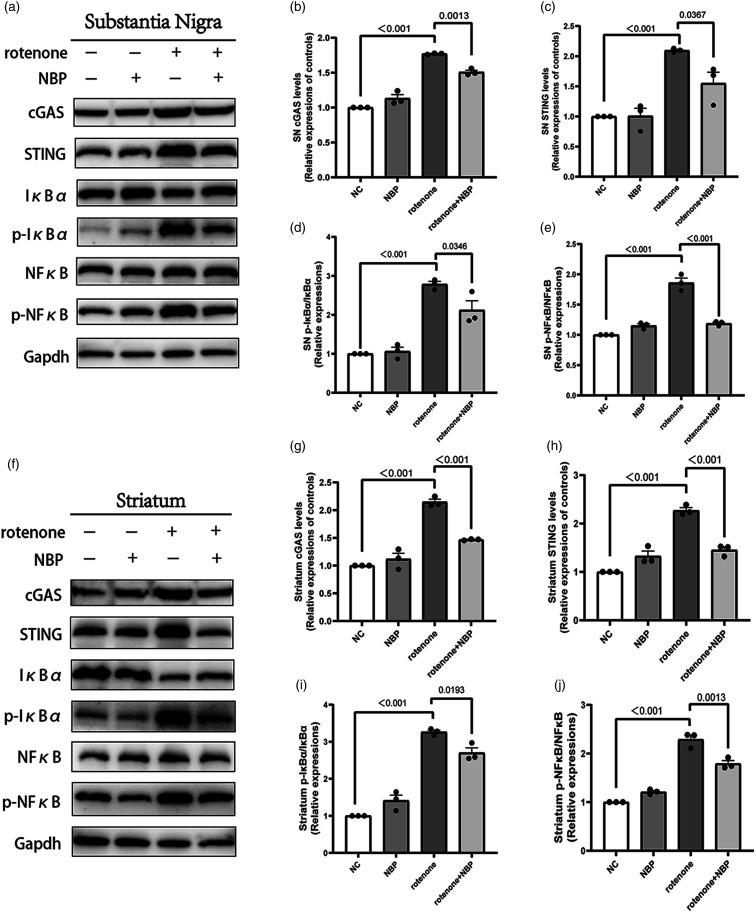

N-Butylphthalide ameliorates mtDNA leakage and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes associated neuroinflammation in rotenone-induced mice

We used qRT-PCR to detect mtDNA leakage into the cytoplasm of the substantia nigra and striatum. We found that NBP reduced rotenone-induced mtDNA leakage in the mouse brain tissues (Figure 6(e)–(f)). We used Western Blot to measure the levels of cGAS, STING, and the ratios of p-NfκB/NfκB and p-IκBα/IκBα proteins in the striatum and substantia nigra. We found that the expression or phosphorylation levels of these proteins were elevated in the striatum and substantia nigra of rotenone-treated mice (Figure 7). Compared to the rotenone group, the content or phosphorylation levels of these proteins in the rotenone + NBP group were significantly reduced (Figure 7). This indicated that NBP inhibited rotenone-induced neuroinflammation through the cGAS-STING pathway.

Figure 7.

NBP reduces cGAS-STING associated neuroinflammation in the substantia nigra and striatum. (a), (f) Expression levels of cGAS, STING, NfκB, p-NfκB, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins in the striatum and substantia nigra were measured using Western Blot. (b)-(e) Statistical analysis of cGAS, STING, NfκB, p-NfκB, IκBα, and p-IκBα protein levels in substantia nigra. (g)-(j) Statistical analysis of cGAS, STING, NfκB, p-NfκB, IκBα, and p-IκBα protein levels in striatum. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 3). p value is provided in all histograms.

Discussion

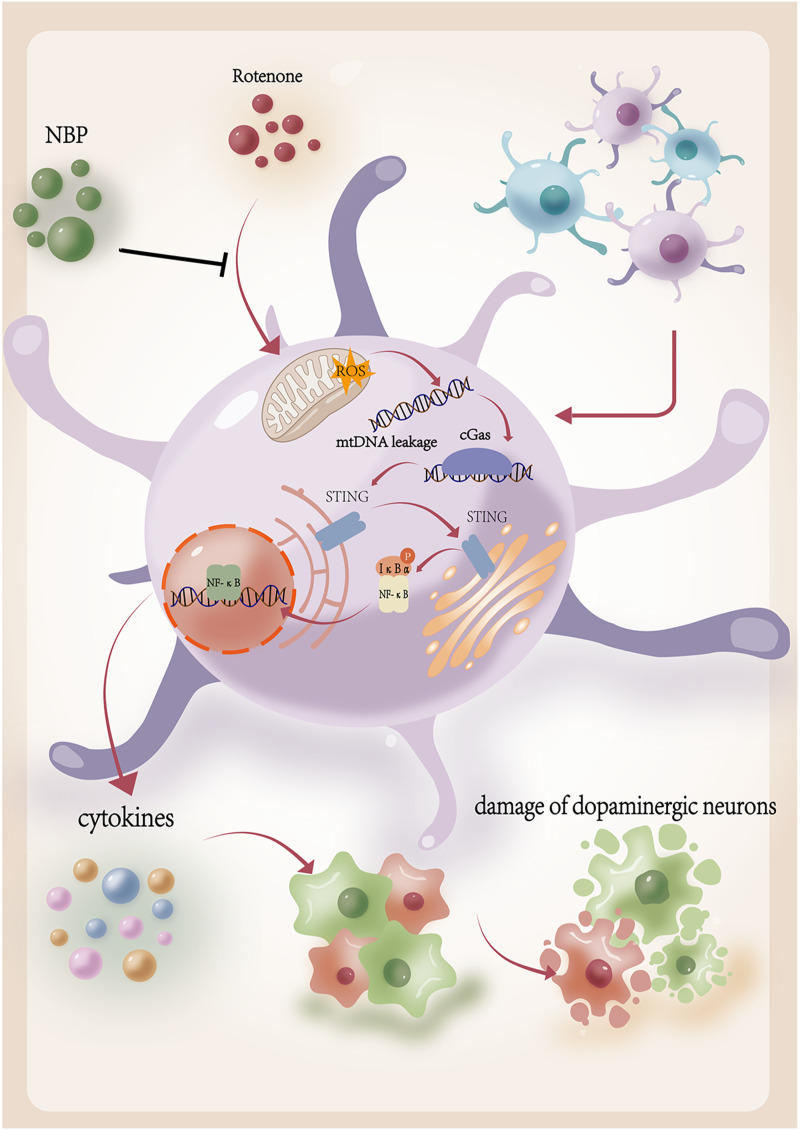

This study demonstrated that NBP reduced neuroinflammation and protected dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in vitro and in vivo (Figure 8). The results showed that rotenone upregulated cGAS-STING signaling and induced an inflammatory response in BV2 cells, which was ameliorated by the STING inhibitor C-176. NBP reduced mtROS production and mitigated rotenone-induced mtDNA leakage. Moreover, NBP improved behavioral impairments and protected against rotenone-induced microglial activation and dopaminergic neuronal damage in PD mice. In addition, NBP inhibited the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway and simultaneously attenuated neuroinflammation. This was indicated by the decrease in the ratios of p-NfκB/NfκB and p-IκBα/IκBα and the production of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6). Our study revealed a novel mechanism by which NBP exhibits protective effects in rotenone-induced PD models.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the protective effect of NBP in rotenone-induced PD models. Rotenone increases mitochondrial ROS levels and mtDNA leakage. The free cytoplasmic mtDNA activates the cGAS-STING pathway and leads to neuroinflammation, which is neurotoxic to dopaminergic neurons. NBP decreases rotenone-induced mitochondrial ROS levels and mtDNA leakage. NBP inhibits the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway and neuroinflammation, which is helpful to delay the progression of degeneration of dopaminergic neuron.

NBP is particularly effective for treating cerebrovascular diseases.22,23 In ischemic stroke, NBP can reduce neuroinflammation by inhibiting the inflammasome in microglia. 37 Furthermore, NBP showed anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects in a repeated cerebral ischemia-reperfusion model. 46 Recently, the possible therapeutic effects of NBP in neurodegenerative diseases have garnered increasing attention.22,47

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. Although some drugs, such as levodopa, can temporarily supplement dopamine and control motor disorders, no disease-modifying therapy has been found. 48 Onset and progression of PD are related to many factors, such as mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and chronic and persistent neuroinflammation.1,49 Microglia are the principal immune cells in the brain that contribute significantly to neuroinflammation. 50 Numerous activated microglia are found in the substantia nigra of patients with PD, suggesting that microglia are closely associated with the onset and progression of PD. 51 Inhibiting the microglial overactivation and excessive neuroinflammation plays a neuroprotective role in PD models.38,52–55

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another significant factor associated with the development of PD.56,57 The constituents and metabolic products of mitochondria, such as mtDNA, can induce inflammatory responses through various signal transduction cascades, including cGAS-STING signaling. 58 Oxidative stress in cells can damage the mitochondria and destroy the integrity of mtDNA, which facilitates mtDNA leakage into the cytoplasm. 31 Studies have shown that mtDNA can promote microglial activation and result in the deterioration of neurological function in ischemic stroke, indicating a possible connection between mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation.59,60

Our results demonstrate that NBP decreases mitochondrial ROS levels and inhibits mtDNA leakage, simultaneously attenuating the excessive activation of microglia and decreasing the release of proinflammatory mediators induced by rotenone in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, NBP eventually alleviated motor and spatial cognitive impairments as well as the loss of dopaminergic neurons in PD mice. NBP plays an important role in both protecting mitochondrial function and inhibiting neuroinflammation, and the specific molecular mechanism that connects mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic inflammation has garnered our interest.

Being one of the most important signaling cascades induced by free cytoplasmic mtDNA, the cGAS-STING pathway contributes extensively to innate immune and inflammatory responses in humans and may be a potential target in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.58,61 Hou et al. showed that reduced free cytoplasmic dsDNA and downregulation of the cGAS-STING pathway could alleviate cellular senescence and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mice. 62 Jauhari et al. showed that mutant huntingtin genes increased ROS levels, promoted mtDNA leakage, activated the cGAS-STING pathway, and caused pathological inflammatory reactions, leading to synaptic loss and neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. 63 In addition, deposition of trans-activation response DNA binding protein-43 induces mtDNA release and upregulates the cGAS-STING pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. 35 Furthermore, mtDNA release and cGAS-STING pathway activation due to mitophagy disorders in Parkin and PINK1 deficient PD mice have been reported. 32 In our study, we observed the upregulation of cGAS-STING in rotenone-treated microglia in vitro, and the inflammatory response was partially inhibited by the STING inhibitor C-176, indicating a close relationship between cGAS-STING signaling and neuroinflammation. In addition, we demonstrated that NBP downregulates the cGAS-STING pathway in rotenone-induced PD models in vivo and vitro and alleviates inflammatory responses.

These results reveal a novel mechanism underlying the protective effect of NBP in PD, establishing an experimental foundation for clinical trials and application of NBP in PD treatment. Moreover, they offer valuable insights for potential therapeutic approaches for PD disease modification and delay of progression.

Limitations of this study

Although the experimental results are valuable, this study had some limitations. First, we demonstrated that NBP alleviates neuroinflammation and protects dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting mtDNA leakage and downregulating the cGAS-STING pathway; however, the exact molecular pathway mechanism of decrease in mtDNA leakage by NBP has not been confirmed. Second, we did not conduct power analysis in this experiment. Third, this study was only conducted in mouse and cell models; therefore, we were unable to observe the actual therapeutic effect in patients with PD. Future studies should focus on cohorts to determine whether the clinical application of NBP can slow disease progression in patients with PD.

Conclusions

Our results establish that NBP exhibits protective effects in rotenone-induced PD models by inhibiting the cGAS-STING pathway and alleviating neuroinflammation. This study revealed a novel molecular mechanism and introduces prospective therapeutic approaches involving NBP in PD treatment. NBP emerges as a promising candidate for disease modification and the delay of PD progression, which is crucial for enhancing the quality of life and lifespan of patients with PD worldwide.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82171245).

Animal welfare: The present study followed national guidelines for humane animal treatment and complied with relevant legislation.

Ethical statement

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained to conduct Animal experiments from the Animal Welfare committee. The Ethics Approval Number is DWLL-2023-134.

ORCID iD

Yuqian Liu https://orcid.org/0009-0004-4034-5828

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. (2017) Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim 3: 17013. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhat S, Acharya UR, Hagiwara Y, et al. (2018) Parkinson's disease: cause factors, measurable indicators, and early diagnosis. Comput Biol Med 102: 234–241. DOI: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis AA, Racette B. (2016) Parkinson disease and cognitive impairment: five new things. Neurology. Clinical practice 6: 452–458. DOI: 10.1212/cpj.0000000000000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Exner N, Lutz AK, Haass C, et al. (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological consequences. EMBO J 31: 3038–3062. DOI: 10.1038/emboj.2012.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. (2003) Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Science 302: 819–822. DOI: 10.1126/science.1087753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michel PP, Hirsch EC, Hunot S. (2016) Understanding dopaminergic cell death pathways in Parkinson disease. Neuron 90: 675–691. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janda E, Boi L, Carta AR. (2018) Microglial phagocytosis and its regulation: a therapeutic target in Parkinson's disease? Front Mol Neurosci 11: 144. DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Boyes BE, et al. (1988) Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-dr in the substantia nigra of parkinsons and alzheimers-disease brains. Neurology 38: 1285–1291. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Micheau O, Tschopp J. (2003) Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell 114: 181–190. DOI: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godoy MCP, Tarelli R, Ferrari CC, et al. (2008) Central and systemic IL-1 exacerbates neurodegeneration and motor symptoms in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain: A Journal of Neurology 131: 1880–1894. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awn101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YJ, Wu TT, Li H, et al. (2019) Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide exerts dopaminergic neuroprotection through inhibition of neuroinflammation. Front Aging Neurosci 11: 44. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannon JR, Tapias V, Na HM, et al. (2009) A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 34: 279–290. DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, et al. (2000) Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci 3: 1301–1306. DOI: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur I, Behl T, Sehgal A, et al. Connecting the dots between mitochondrial dysfunction and Parkinson's disorder: focus mitochondria-targeting therapeutic paradigm in mitigating the disease severity. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021; 28: 37060–37081. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-021-14619-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser DN, Hastings TG. (2013) Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease and monogenic parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis 51: 35–42. DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X, Han B, Zhao Y, et al. (2022) Rosmarinic Acid attenuates rotenone-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Parkinson's disease cell model through abl inhibition. Nutrients 14: 3508. DOI: 10.3390/nu14173508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li PZ, Lv HB, Zhang BH, et al. (2022) Growth differentiation factor 15 protects SH-SY5Y cells from rotenone-induced toxicity by suppressing mitochondrial apoptosis. Front Aging Neurosci 14: 869558, DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.869558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aleksandrova Y, Chaprov K, Podturkina A, et al. (2023) Monoterpenoid epoxidiol ameliorates the pathological phenotypes of the rotenone-induced Parkinson's disease model by alleviating mitochondrial dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 24: 5842. DOI: 10.3390/ijms24065842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherer TB, Betarbet R, Kim JH, et al. (2003) Selective microglial activation in the rat rotenone model of Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 341: 87–90. DOI: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao F, Chen D, Hu QS, et al. (2013) Rotenone directly induces BV2 cell activation via the p38 MAPK pathway. PLoS One 8: e72046, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jing L, Hou LY, Zhang DD, et al. (2021) Microglial activation mediates noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurodegeneration via complement receptor 3 in a rotenone-induced Parkinson's disease mouse model. J Inflamm Res 14: 1341–1356. DOI: 10.2147/jir.S299927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Ma F, Huang LJ, et al. (2018) Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide (NBP): a promising therapeutic agent for ischemic stroke. CNS Neurol Disord - Drug Targets 17: 338–347. DOI: 10.2174/1871527317666180612125843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu ZQ, Zhou Y, Shao BZ, et al. (2019) A systematic review of neuroprotective efficacy and safety of DL-3-N-butylphthalide in ischemic stroke. Am J Chin Med 47: 507–525. DOI: 10.1142/s0192415x19500265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Wang LF, Yang YP, et al. (2023) DL-3-n-butylphthalide (NBP) alleviates poststroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) by suppressing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol 13: 987293. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2022.987293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Que R, Zheng J, Chang Z, et al. (2021) Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide rescues dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease models by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome and ameliorating mitochondrial impairment. Front Immunol 12: 794770. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.794770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo RX, Zhu LH, Zeng ZH, et al. (2021) Dl-butylphthalide inhibits rotenone-induced oxidative stress in microglia via regulation of the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med 21: 597. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang JZ, Chen YZ, Su M, et al. (2010) DL-3-n-Butylphthalide prevents oxidative damage and reduces mitochondrial dysfunction in an MPP+-induced cellular model of Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 475: 89–94. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q, Sun LJ, Chen ZJJ. (2016) Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol 17: 1142–1149. DOI: 10.1038/ni.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T, Chen ZJJ. (2018) The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J Exp Med 215: 1287–1299. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20180139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, et al. (2021) The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 21: 548–569. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-021-00524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao YX, Liu BH, Xu L, et al. (2021) ROS-induced mtDNA release: the emerging messenger for communication between neurons and innate immune cells during neurodegenerative disorder progression. Antioxidants 10: 1917. DOI: 10.3390/antiox10121917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sliter DA, Martinez J, Hao L, et al. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature 2018. 561: 258–262. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Hinkle JT, Patel J, Panicker N, et al. (2022) STING mediates neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in nigrostriatal α-synucleinopathy. PNAS USA 119: e2118819119. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2118819119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Standaert DG, Childers GM. (2022) Alpha-synuclein-mediated DNA damage, STING activation, and neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease. PNAS USA 119: e2204058119. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2204058119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu CH, Davidson S, Harapas CR, et al. TDP-43 triggers mitochondrial DNA release via mPTP to activate cGAS/STING in ALS. Cell 2020. 183: 636-649. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao M, Wang B, Zhang C, et al. (2021) The DJ1-Nrf2-STING axis mediates the neuroprotective effects of Withaferin A in Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Differ 28: 2517–2535. DOI: 10.1038/s41418-021-00767-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu MD, Zheng HR, Liu Z, et al. (2022) Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide reduced neuroinflammation by inhibiting inflammasome in microglia in mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion. Life 12: 1244. DOI: 10.3390/life12081244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang H, Kim S, Lee JM, et al. (2017) Montelukast treatment protects nigral dopaminergic neurons against microglial activation in the 6-hydroxydopamine mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport 28: 242–249. DOI: 10.1097/wnr.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li FF, Ma QF, Zhao HP, et al. (2018) L-3-n-Butylphthalide reduces ischemic stroke injury and increases M2 microglial polarization. Metab Brain Dis 33: 1995–2003. DOI: 10.1007/s11011-018-0307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nezhadi A, Esmaeili-Mahani S, Sheibani V, et al. (2017) Neurosteroid allopregnanolone attenuates motor disability and prevents the changes of neurexin 1 and postsynaptic density protein 95 expression in the striatum of 6-OHDA-induced rats’ model of Parkinson's disease. Biomed Pharmacother 88: 1188–1197. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahader GA, Nash KM, Almarghalani DA, et al. (2021) Type-I diabetes aggravates post-hemorrhagic stroke cognitive impairment by augmenting oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in mice. Neurochem Int 149: 105151. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hussein AM, Bezu M, Korz V. (2018) Evaluating working memory on a T-maze in male rats. Bio-Protocol 8: e2930. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.d'Isa R, Comi G, Leocani L. (2021) Apparatus design and behavioural testing protocol for the evaluation of spatial working memory in mice through the spontaneous alternation T-maze. Sci Rep 11: 21177, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-00402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hollander J, McNivens M, Pautassi RM, et al. (2019) Offspring of male rats exposed to binge alcohol exhibit heightened ethanol intake at infancy and alterations in T-maze performance. Alcohol 76: 65–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Victorelli S, Salmonowicz H, Chapman J, et al. (2023) Apoptotic stress causes mtDNA release during senescence and drives the SASP. Nature 622: 627–636. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06621-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao YR, Hu M, Niu XL, et al. (2022) Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide improves neuroinflammation in mice with repeated cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury through the nrf2-mediated antioxidant response and TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022: 8652741. DOI: 10.1155/2022/8652741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang LJ, Wang S, Ma F, et al. (2018) From stroke to neurodegenerative diseases: the multi-target neuroprotective effects of 3-n-butylphthalide and its derivatives. Pharmacol Res 135: 201–211. DOI: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rotondo R, Proietti S, Perluigi M, et al. (2023) Physical activity and neurotrophic factors as potential drivers of neuroplasticity in Parkinson's Disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 92: 102089. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2023.102089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Araujo B, Caridade-Silva R, Soares-Guedes C, et al. (2022) Neuroinflammation and Parkinson's disease-from neurodegeneration to therapeutic opportunities. Cells 11: 2908. DOI: 10.3390/cells11182908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hickman S, Izzy S, Sen P, et al. (2018) Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 21: 1359–1369. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-018-0242-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Subramaniam SR, Federoff HJ. (2017) Targeting microglial activation States as a therapeutic avenue in Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 9: 176. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen X, Liu Z, Cao BB, et al. (2017) TGF-β1 neuroprotection via inhibition of microglial activation in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol : The Official Journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 12: 433–446. DOI: 10.1007/s11481-017-9732-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang BX, Liu JX, Ju C, et al. (2017) Licochalcone A prevents the loss of dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting microglial activation in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Parkinson's disease models. Int J Mol Sci 18: 2043. DOI: 10.3390/ijms18102043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jing HR, Wang SX, Wang M, et al. (2017) Isobavachalcone attenuates MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease in mice by inhibition of microglial activation through NF-kappa B pathway. PLoS One 12: e0169560. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen YH, Jiang MJ, Li L, et al. (2018) DL-3-n-butylphthalide reduces microglial activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced Parkinson’s disease model mice. Mol Med Rep 17: 3884–3890. DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das NR, Sharma SS. (2016) Cognitive impairment associated with Parkinson's disease: role of mitochondria. Curr Neuropharmacol 14: 584–592. DOI: 10.2174/1570159x14666160104142349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abrishamdar M, Jalali MS, Farbood Y. (2022) Targeting mitochondria as a therapeutic approach for Parkinson’s disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol 43: 1499–1518. DOI: 10.1007/s10571-022-01265-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marchi S, Guilbaud E, Tait SWG, et al. (2023) Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 23: 159–173. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-022-00760-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kong LQ, Li WY, Chang E, et al. (2022) mtDNA-STING Axis mediates microglial polarization via IRF3/NF-kappa B signaling after ischemic stroke. Front Immunol 13: 860977. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.860977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liao YJ, Cheng JB, Kong XX, et al. (2020) HDAC3 inhibition ameliorates ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury by regulating the microglial cGAS-STING pathway. Theranostics 10: 9644–9662. DOI: 10.7150/thno.47651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ding J, Dai YJ, Zhu JH, et al. (2022) Research advances in cGAS-stimulator of interferon genes pathway and central nervous system diseases: focus on new therapeutic approaches. Front Mol Neurosci 15: 1050837. DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1050837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hou Y, Wei Y, Lautrup S, et al. (2021) NAD(+) supplementation reduces neuroinflammation and cell senescence in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease via cGAS-STING. PNAS USA 118: e2011226118. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2011226118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jauhari A, Baranov SV, Suofu Y, et al. (2020) Melatonin inhibits cytosolic mitochondrial DNA-induced neuroinflammatory signaling in accelerated aging and neurodegeneration. The Journal of clinical investigation 130: 3124–3136. DOI: 10.1172/jci135026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request.