Abstract

Introduction

This study examined to what extent supervised aerobic and resistance exercise combined with continued unsupervised exercise training improves cardiorespiratory fitness and corresponding perioperative risk in peripheral artery disease (PAD) patients with intermittent claudication.

Methods

A total of 106 patients (77% male) were enrolled into the study, alongside 155 healthy non-PAD control participants. Patients completed supervised exercise therapy (aerobic and resistance exercises of the upper and lower limbs) twice a week for 10 weeks. Thereafter, 52 patients completed 12 weeks of an unsupervised tailored home-based exercise. Pain-free walking distance (PWD), maximum walking distance (MWD), peak oxygen uptake () and perioperative risk were assessed before and after both exercise interventions.

Results

Patients were highly unconditioned relative to healthy controls (=11.9 vs 24.2ml/kg/min, p=<0.001) with 91% classified as high perioperative risk (peak oxygen uptake <15ml/kg/min). Supervised exercise increased PWD (+44±81m, p=<0.001), MWD (+44±71m, p=<0.001) and (+1.01±1.63ml/kg/min, p=<0.001) and lowered perioperative risk (91% to 85%, p=<0.001). When compared with supervised exercise, the improvements in PWD were maintained following unsupervised exercise (+11±91m vs supervised exercise, p=0.572); however, MWD and decreased (−15±48m, p=0.030 and −0.34±1.11ml/kg/min, p=0.030, respectively) and perioperative risk increased (+3%, p=<0.001) although still below baseline (p=<0.001).

Conclusions

Supervised aerobic and resistance exercise training and, to a lesser extent, unsupervised tailored exercise improves walking capacity and cardiorespiratory fitness and reduces perioperative risk in PAD patients with intermittent claudication.

Keywords: Peripheral artery disease, Intermittent claudication, Exercise training, Cardiorespiratory fitness, Perioperative risk

Introduction

Lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a common disease, affecting an estimated 235 million people globally and associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.1 Leg pain induced by exercise and relieved with rest typifies the clinical diagnosis of intermittent claudication (IC).2 Lifestyle changes combined with exercise training remain a cornerstone of IC management and international guidelines recommend exercise training among first-line therapies for patients with symptomatic PAD.3 The benefits of both aerobic and resistance exercise are well known and include improvements in maximum walking distance (MWD, also known as absolute claudication distance), pain-free walking distance (PWD, also known as initial claudication distance), cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF),4 quality of life and mortality.5,6

It has also been shown that an increase in CRF, assessed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), is associated with improved postoperative survival in patients scheduled for elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair,7 reduced intensive therapy unit requirement and reduced hospital length of stay.8,9 Accordingly, a discriminatory peak oxygen uptake () threshold value of <15ml/kg/min has been identified to categorise those at increased risk of morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery.10 As a likely consequence of physical inactivity, muscle weakness and accompanying comorbidities,11 a recent meta-analysis identified a mean of 15.7±2.8ml/kg/min in IC patients,12 yet their corresponding perioperative risk reduction in response to an exercise intervention has not been explored.

To address this knowledge gap, the present study sought to firstly determine CRF and perioperative risk in patients with IC relative to age-matched healthy controls, and second, to what extent a 10-week supervised aerobic and resistance exercise therapy followed by a 12-week unsupervised exercise therapy potentially improves functional measures of CRF and corresponding implications for perioperative risk stratification.

Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by Cwm Taf University Health Board (CT/838/17) and American Medical International (Texas, USA). All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association,13 with written informed consent obtained from all participants and patients.

Non-PAD controls

For the purposes of comparing baseline CRF, we recruited 155 consecutive non-PAD participants, attending the same hospital at the same time, who were participating in a cardiovascular screening programme due to the presence of risk factors. They were selected retrospectively based on a normal 12-lead electrocardiographic response to a functional diagnostic Bruce protocol graded exercise test to volitional exhaustion. All participants were asymptomatic without claudication and defined as sedentary since they did not engage in any form of recreational activity outside of everyday living.14

Patients

The study cohort was drawn from a consecutive sample of vascular patients with symptomatic atherosclerotic disease who had undergone lower limb vascular imaging via Duplex ultrasound following presentation to their local hospital vascular unit (Royal Glamorgan Hospital, Llantrisant, UK). All patients were bipeds and were allocated to a supervised (hospital-based) exercise training intervention that consisted of a combination of aerobic and resistance-based exercises. Thereafter, patients were allocated to complete an unsupervised (home and community-based) aerobic exercise training intervention.

Clinical history

Patients underwent a thorough medical examination in which demographic information, body mass index (BMI), vascular risk factors, comorbid conditions, claudication history, ankle/brachial index (ABI) and list of current medications were recorded. Obesity was defined by a BMI≥30kg/m2, and overweight as a BMI≥25kg/m2. Hypertension was defined by having at least one of the following conditions: a systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg, a diastolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg, or currently prescribed antihypertensive medications. Dyslipidaemia was defined by having at least one of the following conditions: a cholesterol value ≥5.2mmol/l, a triglyceride value ≥1.7mmol/l, a low-density lipoprotein level ≥3.4mmol/l, a high-density lipoprotein level <1.0mmol/l in men and <1.3mmol/l in women, or currently prescribed lipid-lowering medications. Diabetes was defined by having at least one of the following conditions: a fasting blood glucose ≥7.0mmol/l or currently prescribed oral medication or insulin. A history of lower extremity revascularisation, smoking, cerebral vascular accidents (stroke or transischemic attacks), and previous angina were determined by self-report, and a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was determined if the patient reported that they had been diagnosed by their physician. The presence of uni/bilateral disease was noted by the consultant radiologist including the number of segments affected. Only stenoses of ≥50% were considered radiologically significant.

Inclusion criteria

Each patient was deemed suitable for exercise; diagnosed by an ABI ≤0.90 at rest, stenoses ≥50% by computed tomography angiography or Duplex ultrasound and relevant history. Each patient that chose to participate in the exercise therapy demonstrated an ability to exercise at a level appropriate for the group sessions, with IC being the main limiting factor to continue exercise. Patients were referred to the exercise clinic with additional input from the consultant cardiologist and senior physiotherapist following discussion with the consultant vascular surgeon. They were all suitable for surgery or endovascular intervention but at an early stage of the disease (stage II of Fontaine classification), and the consultant vascular surgeon stated that they could benefit from exercise therapy in the first instance.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded only for the following reasons: lower limb amputation or ulceration, stroke suffered within 6 months, acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery bypass surgery or endovascular angioplasty of coronary arteries within 12 months, aortic aneurysm, advanced kidney or liver failure, failure of the respiratory or circulatory system, active neoplastic disease, advanced chronic venous insufficiency, Buerger’s disease, uncontrolled hypertension, mental disease or dementia, failure to complete all of the baseline tests and failure to complete more than one-third of the exercise intervention sessions.

Exercise interventions in patients

Supervised (hospital-based) exercise

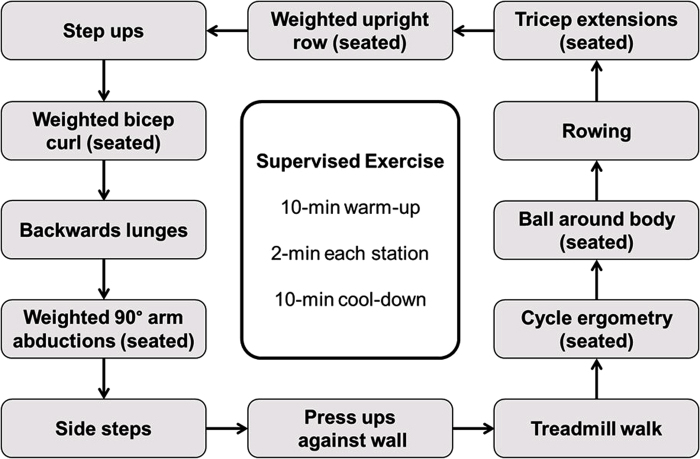

All patients participated in a 10-week senior physiotherapist-led exercise training therapy that consisted of a customised program of aerobic and resistance exercises of the upper and lower limbs (Figure 1). Exercise sessions were held twice weekly (20 sessions in total) using the same calibrated equipment. Each session lasted ~45min and consisted of a 10min seated aerobic warm up, 12 circuit stations each lasting for 2min and a 10min cool down. Patients were encouraged to work into light to moderate pain guided by a four-point subjective scale. If patients reported severe claudication pain, they were advised to change the exercise activity to allow for recovery. Resistance exercises were conducted in the stationary position and were designed specifically to engage upper and lower limb muscle groups. The initial resistance or mass and training device adapted individually to the needs of each patient with careful attention to form (i.e., accommodating full range of motion with the concentric phase synchronised with expiration). The amount of work increased every week, adapted to each case and considering the results obtained by the patient in the previous session, according to the literature.12

Figure 1 .

Components of the supervised exercise training therapy

Unsupervised (community-based) exercise

Following successful completion of the supervised exercise therapy, patients were encouraged to continue with a 12-week structured community-based exercise therapy making use of schemes running in local leisure centres. This was designed to be as similar as possible to the supervised therapy in terms of exercise mode, duration, exercise intensity, and frequency and encouraged longer-term improvements in exercise habits; patients were free to adapt this activity according to their preference. Patients received an exercise logbook to record their training sessions and had access to the physiotherapist for feedback and advice if required.

Measurements

Patient medical history and associated demographics were determined as outlined previously. Remaining measurements were performed at baseline and following completion of the supervised (10 weeks) and unsupervised (12 weeks, 22 weeks cumulative) exercise therapy.

Resting heart rate and blood pressure

Patients were rested for 10min in the seated position before measurement of blood pressure via auscultation (Accuson Aneroid Sphygmomanometer, Cirencester, UK). Heart rate (HR) was recorded using an electrocardiogram-calibrated short-range telemetry system (Polar, Kempele, Finland). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as one-third [systolic blood pressure (SBP) – diastolic blood pressure (DBP)]+DBP and rate pressure product (RPP) as SBP×HR.

Six-minute walking test

Patients performed an overland six-minute walking test (6MWT) according to the standardised protocol outlined by The American Thoracic Society.15

Walking distance

MWD was defined as the total distance in metres travelled by the patient before claudication pain was so severe they had to stop walking, and the initial claudication distance or PWD as the distance walked before the onset of claudication pain (expressed in both metres and as percentage of the MWD). The rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was recorded using the 6–20 Borg Scale,16 and perceived claudication pain (PP) via the claudication 0–4 pain rating scale. was calculated from the MWD using the generalised prediction equation derived from patients with diverse cardiopulmonary disease standard error of estimate of 1.1ml/kg/min17:

The CRF was estimated for each patient based on the results of the 6MWT and the calculated using the previous formula.

Perioperative risk stratification

In accordance with recent research about assessment of risk of early mortality following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair by preoperative cardiopulmonary exercise testing,10 a discriminatory threshold value of <15ml/kg/min was employed to classify an individual to be at high perioperative risk. The used for the control group was measured during a cardiopulmonary exercise testing and the used for the PAD group was calculated from the MWD. In the absence of a dedicated risk model for the PAD patients, the risk model used is based on studies evaluating the morbidity/mortality of patients undergoing elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistics Package for Social Scientists (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 28.0). Distribution normality was confirmed using repeated Shapiro–Wilk W tests. A combination of paired and independent samples t-tests were employed to determine the effects of exercise training within and between groups. The number of patients in each group was analysed using chi-square tests to assess how exercise training impacted perioperative risk. Significance for all two-tailed tests was established at p<0.05 and data presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Compliance

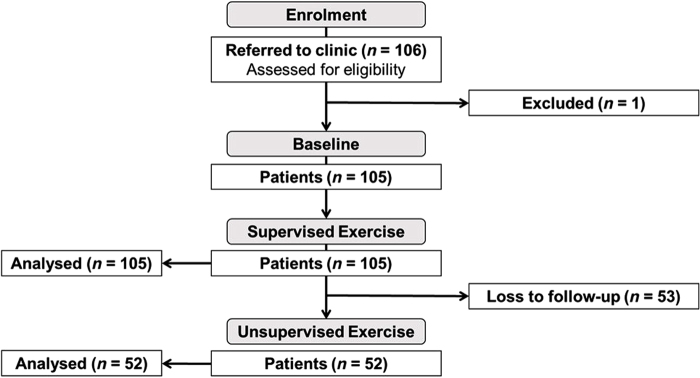

A total of 105 patients (only 1 loss to follow-up) completed the supervised exercise therapy (Figure 2). Of these, 52 patients went on to complete the unsupervised exercise therapy.

Figure 2 .

Patient flow. n, sample size.

Demographics

Patients who completed the supervised exercise therapy were aged 66±8years old (78% males), compared with the control group, who were 65±8years old with 88% of men. As anticipated, vascular risk factors were more prevalent in the claudication patients (Table 1). Table 2 summarises the severity of their PAD and surgical history.

Table 1 .

Participant and patient characteristics

| Group: | Controls | Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise subgroup: | None (n=155) | Supervised (n=105) | Unsupervised (n=52) |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 65±8 | 66±8 | 68±8 |

| Males (n/%) | 137/88 | 82/77* | 35/67* |

| Females (n/%) | 18/12 | 24/23* | 17/33* |

| Vascular risk factors | |||

| Overweight (n/%) | 128/83 | 88/83 | 43/83 |

| Obese (n/%) | 79/51 | 60/57 | 30/58 |

| Smoker (n/%) | 48/31 | 67/63* | 30/58* |

| Diabetes (n/%) | 10/7 | 25/24* | 11/21* |

| Hypertension (n/%) | 8/5 | 82/77* | 41/79* |

| Dyslipidaemia (n/%) | 5/3 | 77/73* | 35/67* |

| Angina/MI (n/%) | 0/0 | 42/40* | 21/40* |

| CVA/TIA (n/%) | 4/3 | 6/6 | 3/6 |

| COPD (n/%) | 0/0 | 24/23* | 11/21* |

| Medication | |||

| Statins (n/%) | 5/3 | 78/74* | 38/73* |

| Aspirin (n/%) | 4/3 | 102/96* | 50/96* |

| Warfarin (n/%) | 0/0 | 2/2 | 1/2 |

| Clopidogrel (n/%) | 0/0 | 2/2 | 1/2 |

| Beta-blockers (n/%) | 8/5 | 33/31* | 12/23* |

| ACE inhibitors (n/%) | 0/0 | 61/58* | 29/56* |

| Calcium channel antagonists (n/%) | 0/0 | 49/46* | 22/42* |

| Nitrates/K+ATP channel agonists (n/%) | 0/0 | 16/15* | 8/15* |

| Diuretics (n/%) | 0/0 | 29/27* | 18/35* |

| Antidiabetic medication (n/%) | 10/7 | 25/24* | 10/19* |

Values are mean±SD or frequency (n)/percentage (%). ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; MI = myocardial infarction; TIA = transient ischaemic attack.

*p<0.05 vs controls.

Table 2 .

Peripheral artery disease demographics

| Subgroup: | Supervised (n=105) | Supervised+Unsupervised (n=52) |

|---|---|---|

| Previous surgery | ||

| Lower extremity revascularisation (n/%) | 27/25 | 17/33 |

| Laterality | ||

| Unilateral lesions (n/%) | 48/45 | 19/36 |

| Bilateral lesions (n/%) | 57/54 | 33/64 |

| Bilateral:Unilateral (AU) | 1.18 | 1.74 |

| Distribution | ||

| Affected limbs (n) | 163 | 85 |

| Single segment (n) | 61 | 37 |

| Multiple segments (n) | 102 | 48 |

| Multiple:Single (AU) | 1.67 | 1.30 |

Values are frequency (n)/percentage (%). AU = arbitrary units.

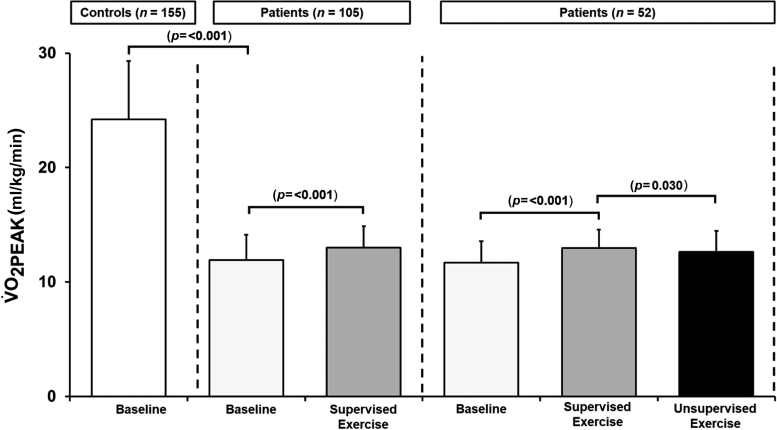

Cardiorespiratory fitness

At baseline, estimated CRF of patients was 50% lower than that of controls (=12±2ml/kg/min vs 24±5ml/kg/min, p=<0.001, Figure 3) highlighting how poorly conditioned they were. increased following supervised exercise (+1.1±1.4ml/kg/min; p=<0.001, Figure 3). In patients who subsequently completed unsupervised exercise, decreased (−0.3±1.1ml/kg/min, p=0.030; Figure 3) though it remained elevated compared with baseline pretraining values (p=<0.001). Patient BP, HR, RPE and PP remained unchanged following supervised and unsupervised exercise (all p=>0.05, Table 3).

Figure 3 .

Cardiorespiratory fitness before and in response to supervised and unsupervised exercise training. Values are mean±SD.

Table 3 .

Cardiorespiratory and ambulatory responses to exercise training

| Subgroup: | Supervised (n=105) | Supervised+Unsupervised (n=52) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timepoint: | Pre | Post | Pre | Post(Supervised) | Post(Supervised+Unsupervised) |

| Cardiopulmonary (Rest) | |||||

| HR (b/min) | 70±12 | 72±11 | 69±10 | 71±11 | 73±12 |

| Δ (b/min) | 2±8 | 2±6 | 3±8 | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 147±20 | 145±19 | 144±15 | 147±19 | 145±18 |

| Δ (mmHg) | −3±22 | 3±22 | 1±17 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) | 80±12 | 78±11 | 80±10 | 81±12 | 79±13 |

| Δ (mmHg) | −3±12 | 0±13 | −1±15 | ||

| MAP (mmHg) | 102±13 | 100±13 | 101±9 | 102±13 | 101±13 |

| Δ (mmHg) | −3±14 | 1±14 | 0±13 | ||

| RPP (×103 AU) | 10.3±2.1 | 10.4±2.2 | 10.0±1.5 | 10.5±2.2 | 10.5±2.2 |

| Δ (×103 AU) | 0.1±0.2 | 0.5±1.9 | 0.5±2.1 | ||

| Ambulatory (Exercise) | |||||

| PWD (m) | 127±90 | 170±108* | 116±77 | 149±81 | 159±75* |

| Δ (m) | 44±81* | 33±81 | 44±88* | ||

| PWD (%) | 38±23 | 45±24* | 37±25 | 41±19 | 47±20 |

| Δ (%) | 8±21* | 4±24 | 10±24 | ||

| MWD (m) | 304±95 | 348±86* | 293±82 | 349±70* | 334±80*,† |

| Δ (m) | 44±71* | 56±58* | 41±72*,† | ||

| RPE (AU) | 10±3 | 11±3 | 10±3 | 11±2 | 12±3 |

| Δ (AU) | 0±3 | 1±3 | 1±4 | ||

| PP (AU) | 2±1 | 2±1 | 2±1 | 2±1 | 2±1 |

| Δ (AU) | 0±1 | 0±1 | 0±1 | ||

Values are mean±SD. Δ is change calculated from baseline (Pre). AU = arbitrary units; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean arterial pressure; MWD = maximum walking distance; PP = perceived claudication pain; PWD = pain-free walking distance; RPE = rating of perceived exertion; RPP = rate pressure product; S/DBP = systolic/diastolic blood pressure.

*p<0.05 vs Pre within subgroup.

†p<0.05 vs Post(Supervised) within subgroup.

Maximum walking distance

Supervised exercise increased MWD by 24±41% (+44±71m, p=<0.001), whereas a decrease was observed following unsupervised exercise (−15±48m, p=0.030, Table 3), albeit still elevated above baseline (p=<0.001).

Pain-free walking distance

PWD increased following supervised exercise (+44±81m, p=<0.001; Table 3) and was maintained following unsupervised exercise (+11±91m, p=0.572; Table 3). Males recorded a more marked increase in PWD, compared with females (+58±78m vs +4±83m, p=0.043; Table 4), whereas obese patients recorded a lower increase in PWD (+24±77m vs +74±81m; p=0.022; Table 4), compared with non-obese patients.

Table 4 .

Supervised exercise responses according to cardiovascular risk factors

| Independent variable | MWD m | O2PEAK ml/kg/min | PWD m | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ♂ | +49 ±64 | +1.14 ±1.48 | +58 ±78‡ |

| ♀ | +24 ±89 | +0.56 ±2.05 | +4 ±83‡ | |

| Obesity | + | +43 ±80 | +0.99 ±1.84 | +24 ±77‡ |

| − | +45 ±58 | +1.03 ±1.34 | +74 ±81‡ | |

| CVA/TIA | + | +13 ±37 | +0.31 ±0.85 | −22 ±80 |

| − | +46 ±72 | +1.05 ±1.66 | +52 ±80 | |

| COPD | + | +20 ±99 | +0.45 ±2.27 | +37 ±64 |

| − | +51 ±60 | +1.17 ±1.37 | +48 ±88 | |

| Revascularisation | + | +49 ±69 | +1.13 ±1.59 | +73 ±79 |

| − | +42 ±72 | +0.96 ±1.66 | +25 ±79 | |

| Statins | + | +36 ±70* | +0.82 ±1.61† | +50 ±85 |

| − | +67 ±70* | +1.53 ±1.61† | +32 ±75 | |

| CCA | + | +31 ±74 | +0.71 ±1.71 | +39 ±110 |

| − | +55 ±67 | +1.26 ±1.54 | +49 ±63 | |

Values are mean±SD. Data expressed as the absolute change relative to baseline. CCA = calcium channel antagonists; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; MWD = maximum walking distance (n=105) ; PWD = pain-free walking distance (n=58); TIA = transient ischaemic attack; O2PEAK = oxygen uptake (n=105).

*p<0.05 vs given subgroup for MWD.

†p<0.05 vs given subgroup for O2PEAK.

‡p<0.05 vs given subgroup for PWD.

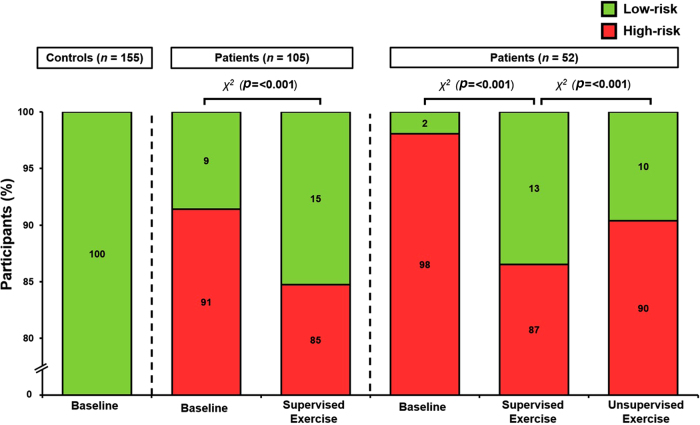

Perioperative risk

At baseline, 91% of patients were classified as high perioperative risk given a <15ml/kg/min, whereas all controls were considered low risk (Figure 4). Supervised exercise and the corresponding improvement in estimated CRF reduced perioperative risk (−6%, p=<0.001; Figure 4). Unsupervised exercise failed to maintain this improvement and increased perioperative risk (+3% vs supervised exercise, p=<0.001; Figure 4), although still below baseline (p=<0.001).

Figure 4 .

Perioperative risk stratification. Risk stratification based on peak oxygen uptake () boundary threshold of <15ml/kg/min (high-risk) and >15ml/kg/min (low-risk).10 χ, chi-square.

Discussion

The present study has identified three important findings. First, it puts into clear perspective precisely how physically deconditioned PAD patients with IC are relative to age- and sedentary-matched healthy controls. Second, supervised and, to a lesser extent, unsupervised exercise, improves functional walking capacity and CRF, responses that were suppressed in females and as a function of obesity. Third, from a practical perspective, the exercise-induced improvement in CRF translated into a marked reduction in perioperative risk, which has important clinical implications for patient care and management.

A subjective assessment of a patient’s functional capacity by an experienced clinician forms the primary component of preoperative evaluation,18 whereby diminished capacity increases the likelihood of complications and mortality following surgery.19 In contrast, the more objective, formal assessment of CRF using established cardiopulmonary metrics including VO2PEAK allows for a more accurate measure of whether a patient will tolerate major surgery.20 In the present study, PAD patients were defined by extremely low basal CRF that was ∼50% lower than ‘already’ poorly conditioned physically inactive, albeit healthy, controls, highlighting that our patients were even more deconditioned than pre-existing literature suggests.12 This difference is possibly related to the older age and increased severity of PAD and associated comorbidities exhibited by the patients in our study compared with those included in previous RCTs.21

Importantly, our findings confirm the therapeutic benefits conferred by supervised exercise training for PAD patients with IC as indicated by marked increases in walking capacity and CRF, reflected by functional improvements in MWD, PWD and , consistent with previous research.4 While the underlying mechanisms for these improvements are likely multifactorial, an increase in pain tolerance and improvements in redox status comprising increased vascular nitric oxide bioavailability facilitated by an ‘upstream’ reduction in free radical-mediated oxidative stress and inflammation are thought to play pivotal roles.22-24 A recent review shows that exercise positively modulates pathways related to inflammation and the atherosclerotic process and may attenuate the progression of lower limb myopathy.25 It should also be noted that our data confirm previous research,25,26 whereby exercise training was less effective in obese patients and women, further supporting the development of arguably more ‘targeted’, intensive exercise training interventions for these populations. Furthermore, our findings encourage the notion that supervised exercise training should be prioritised over ‘go home and exercise’ advice. The reduction in MWD and CRF, and corresponding increase in perioperative risk (+3%) observed following unsupervised exercise was likely attributable to a lower intensity or frequency of exercise, which is often observed during unsupervised home-based exercise.27 If supervised exercise training is not feasible, previous research has suggested that regular meetings or phone calls can be effective for maintaining patient adherence to an exercise protocol to counter this decline in functional capacity.28,29

A ‘high-risk’ surgical patient, accounts for ∼13% of cases yet contributes to a disproportionate >80% of all postoperative complications and mortality.30 A high-risk patient, defined by a <15ml/kg/min, is at increased risk of death within 30–90 days of elective abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair.10 At baseline, 91% of our PAD patients were considered high risk. Their risk decreased with supervised exercise and was further maintained following the unsupervised exercise intervention. These results encourage the systematic prescription of exercise training for PAD patients with IC before, or indeed as an alternative to, surgical revascularisation. Future studies should look to further stratify/optimise perioperative risk in this specific population using cardiopulmonary exercise testing to directly assess and associated metrics.31

We acknowledge that this study has some limitations, constrained in part by the unavoidable challenges associated with patient recruitment, compliance, and access to specialist infrastructure/resources in the hospital (NHS) setting. First, we were logistically unable to directly perform cardiopulmonary exercise testing for a direct assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness () in PAD patients, owing to limited resources and select differences in the care pathway for these patients. Instead, we opted to assess indirectly using a validation approach. Second, the increase in MWD reported in the current study was relatively low in comparison with the improvements documented following treadmill walking exercise training (∼44m vs 277–326m).32,33 This may be related to the fact that the MWD was assessed by a 6MWT—a test that is not designed for this purpose and does not allow comparison with the treadmill. Furthermore, the use of a treadmill is known to overestimate performance and the present study included resistance exercise, which has shown to be inferior to treadmill walking exercise for improving MWD.34,35 Third, the perioperative risk prediction model used was based on studies evaluating the morbidity/mortality of patients undergoing elective surgery for AAA. Although vascular patients often have a similar profile defined by a multitude of cardiovascular disease risk factors, the perioperative risk may not be fully generalisable to PAD patients.

In conclusion, these findings advocate for routine prescription of supervised aerobic and resistance exercise, and to a lesser extent unsupervised home-based exercise, both as a treatment option to increase claudication distances and for those patients requiring operative intervention for revascularisation in a bid to reduce perioperative risk in poorly conditioned PAD patients with IC.

Acknowledgements

Tom Evans, David Bosanquet, Elaine Townsend, Gareth Morris-Stiff.

Funding

D.M.B. is supported by a Royal Society Wolfson Research Fellowship (WM170007). DL is supported by the Société Française de Médecine Vasculaire and the Groupement de Coopération Sanitaire G4.

Conflicts of interest

D.M.B. is Editor-in-Chief of Experimental Physiology, Chair of the Life Sciences Working Group, member of the Human Spaceflight and Exploration Science Advisory Committee to the European Space Agency, member of the Space Exploration Advisory Committee to the UK Space Agency and member of the National Cardiovascular Research Network (Wales). DMB is also affiliated to the companies FloTBI Inc., BrainEx Inc., and OrgEx Inc. focused on the technological development of novel biomarkers of brain injury in humans. MB is a Consultant for Terumo & JOTEC/CryoLife.

References

- 1.Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Yet al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e1020–e1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank U, Nikol S, Belch Jet al. ESVM guideline on peripheral arterial disease. VASA 2019; 48: 1–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aboyans V, Ricco J-B, Bartelink M-LELet al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European society for vascular surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries. Endorsed by: the European stroke organization (ESO)The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and of the European society for vascular surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 763–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmenter BJ, Dieberg G, Smart NA. Exercise training for management of peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2015; 45: 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane R, Harwood A, Watson L. et al. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 12: CD000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris DR, Rodriguez AJ, Moxon JVet al. Association of lower extremity performance with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with peripheral artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3: e001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant SW, Hickey GL, Wisely NAet al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and survival after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair†. Br J Anaesth 2015; 114: 430–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodyear SJ, Yow H, Saedon Met al. Risk stratification by pre-operative cardiopulmonary exercise testing improves outcomes following elective abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery: a cohort study. Perioper Med (Lond) 2013; 2: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prentis JM, Trenell MI, Jones DJet al. Submaximal exercise testing predicts perioperative hospitalization after aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2012; 56: 1564–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartley RA, Pichel AC, Grant SWet al. Preoperative cardiopulmonary exercise testing and risk of early mortality following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland Pet al. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA 2004; 292: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fassora M, Calanca L, Jaques Cet al. Intensity-dependent effects of exercise therapy on walking performance and aerobic fitness in symptomatic patients with lower-extremity peripheral artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Med 2022; 27: 158–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams JR. The declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86: 650–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey DM, Marley CJ, Brugniaux JVet al. Elevated aerobic fitness sustained throughout the adult lifespan is associated with improved cerebral hemodynamics. Stroke 2013; 44: 3235–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwala P, Salzman SH. Six-minute walk test: clinical role, technique, coding, and reimbursement. Chest 2020; 157: 603–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehabil Med 1970; 2: 92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross RM, Murthy JN, Wollak IDet al. The six minute walk test accurately estimates mean peak oxygen uptake. BMC Pulm Med 2010; 10: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stokes JW, Wanderer JP, McEvoy MD. Significant discrepancies exist between clinician assessment and patient self-assessment of functional capacity by validated scoring tools during preoperative evaluation. Perioper Med (Lond) 2016; 5: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sepehri A, Beggs T, Hassan Aet al. The impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 148: 3110–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey DM, Halligan CL, Davies RGet al. Subjective assessment underestimates surgical risk: on the potential benefits of cardiopulmonary exercise testing for open thoracoabdominal repair. J Card Surg 2022; 37: 2258–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Parker DE. Optimal exercise program length for patients with claudication. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55: 1346–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harwood A-E, Cayton T, Sarvanandan Ret al. A review of the potential local mechanisms by which exercise improves functional outcomes in intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg 2016; 30: 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrade-Lima A, Silva Junior N, Chehuen Met al. Walking training improves systemic and local pathophysiological processes in intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2021; 61: 954–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey DM, Rasmussen P, Overgaard Met al. Nitrite and S-nitrosohemoglobin exchange across the human cerebral and femoral circulation: relationship to basal and exercise blood flow responses to hypoxia. Circulation 2017; 135: 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Addison O, Ryan AS, Prior SJet al. Changes in function after a 6-month walking intervention in patients with intermittent claudication who are obese or nonobese. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2017; 40: 190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gommans LNM, Scheltinga MRM, van Sambeek MRHMet al. Gender differences following supervised exercise therapy in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2015; 62: 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degischer S, Labs K-H, Hochstrasser Jet al. Physical training for intermittent claudication: a comparison of structured rehabilitation versus home-based training. Vasc Med 2002; 7: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fakhry F, Spronk S, de Ridder Met al. Long-term effects of structured home-based exercise program on functional capacity and quality of life in patients with intermittent claudication. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92: 1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pymer S, Ibeggazene S, Palmer Jet al. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of home-based exercise programs for individuals with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2021; 74: 2076–2085.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearse RM, Harrison DA, James Pet al. Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Crit Care 2006; 10: R81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose GA, Davies RG, Appadurai IRet al. Cardiorespiratory fitness is impaired and predicts mid-term postoperative survival in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm disease. Exp Physiol 2018; 103: 1505–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cucato GG, Chehuen Mda R, Costa LAet al. Exercise prescription using the heart of claudication pain onset in patients with intermittent claudication. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013; 68: 974–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardner AW. Sex differences in claudication pain in subjects with peripheral arterial disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002; 34: 1695–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDermott MM, Guralnik JM, Tian Let al. Comparing 6-minute walk versus treadmill walking distance as outcomes in randomized trials of peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg 2020; 71: 988–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiatt WR, Wolfel EE, Meier RH, Regensteiner JG. Superiority of treadmill walking exercise versus strength training for patients with peripheral arterial disease. implications for the mechanism of the training response. Circulation 1994; 90: 1866–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]