Abstract

Almost half of infertility cases involve male infertility. Understanding the consequence of a diagnosis of male infertility, as a sole or partial contributor to the couples’ infertility, to the mental health of men is required to ensure clinical care meets their psychological needs. The aim of this systematic analysis was to synthesize the evidence regarding whether men diagnosed with male factor infertility experience greater psychological distress than (1) men described as fertile and (2) men in couples with other infertility diagnoses. Online databases were searched using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) headings and keywords relating to male infertility and psychological distress. The search yielded 1016 unique publications, of which 23 were included: 8 case–control, 14 prospective cohort, and 1 data linkage studies. Seven aspects of psychological distress were identified depression, anxiety, self-esteem, quality of life, fertility-related stress, general psychological stress or well-being, and psychiatric conditions. Case–control studies reported that men with male factor infertility have more symptoms of depression, anxiety and general psychological distress, worse quality of some aspects of life, and lower self-esteem than controls. When men with male factor infertility were compared to men in couples with other causes of infertility, there were few differences in the assessed aspects of psychological distress. Despite methodological limitations within the studies, this systematic analysis suggests that the experience of infertility, irrespective of its cause, negatively affects men’s mental health and demonstrates the need for assisted reproduction technology (ART) providers to consider men undergoing assisted reproduction as individuals with their own unique support needs.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, infertility, male, mental health, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Formalized patient-centered care processes are increasingly being implemented in assisted reproductive technology (ART) practice.1,2,3 Patient-centered care is defined as “care that is respectful of and responsive to the individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”.4

One of the biggest challenges for ART health professionals in providing patient-centered care is that, in most instances, the couple is the “patient”, one entity whose goal is to achieve a live birth, rather than two individuals with independent preferences, needs, and values. Moreover, the cause of infertility may lie solely with one or the other of the members of the couple, be attributed to both parties, or be unknown. Therefore, individuals within each of these subgroups may require specific support. Finally, for the most part, regardless of the diagnosis of infertility, it is the female who must undergo the invasive and uncomfortable treatment. As such, the focus of care is on the woman, with the man often left feeling that he is not involved as an equal partner.5,6

Among couples seeking ART, however, both parties contribute emotionally and biologically to the shared goal of achieving parenthood. The desire and expectation to become a parent are similar for men and women.7,8 Although the contribution of male factor infertility to couple childlessness is almost equal to that of female factors,9 most research on the psychological support needs during ART has focused on women.10

Dissatisfaction with care11 and specifically the care given to the male partner6,12 are reported to be common reasons for ceasing ART treatment or changing clinics. Feelings of neglect, unimportance, or disassociation from the treatment process are also commonly expressed by men,13 potentially adding to the psychological distress that accompanies infertility and ART treatment. Therefore, when considering how patient-centered care can mitigate men’s ART-related distress, the psychological impact on men of infertility diagnosis and treatment needs to be better understood. Some early empirical studies found that men with male factor infertility suffer greater distress than men in couples with other infertility diagnoses,14,15,16 suggesting that this group requires clinical focus.

The aim of this systematic analysis was to synthesize the evidence about the psychological consequences of a diagnosis of male factor infertility to guide the development of patient-centered ART care that meets the needs of infertile men.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources and searches

To answer the question of whether men diagnosed with male factor infertility experienced greater psychological distress than men described as fertile (control group) or men in couples with other infertility diagnoses, a systematic analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.17 The search strategy was designed by a specialist information analyst. A search of online databases (OVID MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and PubMed) was conducted in October 2022 to identify published studies relating to a combination of MeSH headings and keywords. These included “infertile*”, “sub-fertil*”, “male (or men)”, and “coping”, “quality of life”, “emotions”, “anger”, “anxiety”, “psychological distress”, “guilt”, “depression”, “masculinity”, or “social stigma”.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Quantitative experimental studies were included if they were published in a peer-reviewed English language journal between January 2000 and October 2022, reported on psychological distress in males experiencing infertility and had a comparison group.

Studies were excluded if they included participants with a known medical condition causing infertility (e.g., testicular cancer and Klinefelter syndrome), the results were not disaggregated; only descriptive data were reported, population norms were used as a comparison, or psychological distress was not an outcome measure.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Search results were exported into EndNote (EndNote 20, Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Titles and abstracts were screened by the lead author (SNB). Full-text articles were reviewed independently by all three authors.

The data extracted from included studies were aim, study design, number of participants, inclusion criteria, recruitment setting, participant characteristics (e.g., age), infertility diagnosis, data collection tools, outcome measure, timing of assessment, and main findings.

The quality of the studies was assessed independently by all authors using QualSyst developed by Kmet et al.18 This assessment tool provides a systematic, reproducible, and quantitative way of assessing the quality of quantitative studies. The QualSyst scores range between 0 and 1.0.

Any discrepancies in inclusion/exclusion or quality assessment were resolved through discussion.

RESULTS

Search results

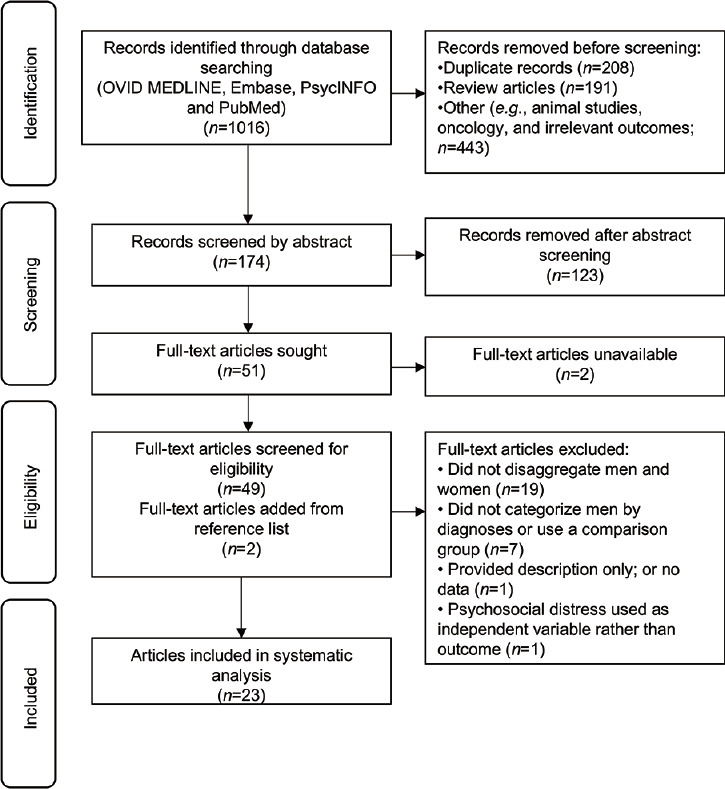

The database search yielded 1016 records, from which 208 duplicates were removed (Figure 1). An additional 842 records were removed as they were not relevant or met the exclusion criteria after the title review. After the screening of abstracts, 51 full-text articles were reviewed. Of these, 28 were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria or providing only descriptive data. Full-text copies of two articles19,20 were unavailable online, and a request for a copy from the corresponding author yielded no response. Two articles were added after handsearching manuscript reference lists. A total of 23 articles were included in the systematic analysis.

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram of literature search and study selection.

The study characteristics and main findings are described in Table 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of case-control studies reporting psychological distress in infertile men compared to men describe as fertile

| Author (year); location | Male participants (n) | Source of recruitment | Age and ID (year), mean±s.d. | Psychosocial assessment instrument | Outcome measures | Timing of psychosocial assessment | Main findings relevant to psychological distress in MF infertility | QA score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhillon et al. (2000);24 Canada | Cases 1 (infertile men): 30 Cases 2 (unexplained infertility): 30 Controls: 30 |

Cases: hospital based academic fertility clinic Controls: physician in obstetric clinic. Partners of controls were currently pregnant |

Cases 1: 36.4±1.3 ID: 1.6±0.3 Cases 2: 35.5±1.3 ID: 3±0.4 Controls: 34.2±1.4 |

1. IPAT Depression Scale49

2. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory50 3. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory51 4. Index of Self Esteem52 5. Dyadic Adjustment Scale53 6. Family Inventory of Life Events and Change54 7. Ways of Coping Inventory55 |

a. Depression b. Anxiety c. Anger d. Self-esteem e. Quality of the relationship f. Recent and past stresses influencing mood g. Personal coping strategies |

During treatment | No significant differences on any measure between groups except Family Inventory of Life Events and change where stress was higher in the fertile group, whose partners were pregnant, compared to the infertile or unexplained groups | 0.54 |

| Drosdzol and Skrzypulec (2008)34 and (2009);25 Poland | Cases: 188 Controls: 190 |

Cases: patients in O and G clinics and infertility outpatient clinic under review for infertility diagnosis Controls: partners of patients in outpatient gynaecological clinics who attended for routine appointments |

Cases: 31.4±4.7 ID: NR Controls: 32.8±6.5 |

1. SF-3645,56

2. International Index of Erectile Function57 3. Becks Depression Inventory58 4. Beck’s Anxiety Inventory59 |

a. QoL b. Sexual functioning c. Depression d. Anxiety |

At least 3 months following diagnosis | Cases and controls similar on QoL measure Cases scored significantly lower on sexual desire and intercourse satisfaction than controls Cases scored significantly higher on both depression and anxiety than controls Men with male infertility scored the highest and men in couples with female fertility scored the lowest on the depression scale compared to all other groups No differences by aetiology on the anxiety scale |

2008: 0.95 2009: 0.91 |

| Akhondi et al. (2013);42 Iran | Cases: 80 Controls: 40 |

Cases: infertile men attending fertility clinic Controls: attended the same clinic as cases but with no infertility diagnosis |

Cases: 37.5±7.3 ID: 7±1.1 Controls: 35±4.8 |

Author devised questionnaire of demographics and psychosocial development42 | a. “Positive traits”: trust, autonomy, initiative, industry, identity, intimacy, generativity, integrity b. “Negative traits”: mistrust, shame and doubt, guilt, inferiority, confusion, isolation, stagnation, despair |

NR | Controls showed significantly higher scores, indicating better psychosocial development, in the areas of trust, autonomy, identity, generativity and integrity Group differences on negative traits were NR |

0.36 |

| Amamou et al. (2013);21 Tunisia | Cases: 100 Controls: 100 |

Cases: patients in the reproductive medicine unit of local hospital Controls: source NR |

Cases: NR ID: 5.2±4.6 |

1. The Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R)60

2. HAD-S61 3. RSES62 |

a. Psychotic symptoms b. Anxiety c. Depression d. Self-esteem |

NR | Scores on psychotic symptoms, depression and anxiety measures significantly higher in cases than controls Self-esteem scores significantly lower in cases than controls |

0.64 |

| El Kissi et al. (2014);35 Tunisia | Cases: 100 Controls: 100 |

Cases: patients in the reproduction medicine unit of the local hospital Controls: parents of children attending first vaccination visit a local public health center. | Cases: 38.7±5.9 ID: NR Controls: 37.6±5.7 |

1. SF-3645 | a. Health related QoL | Cases: after diagnosis63 Controls: at child’s vaccination visit | Cases had lower MCS scores than controls, indicating poorer mental well-being Cases had lower scores in the domains of vitality, social functioning and role-emotional than controls | 0.72 |

| Karimzadeh et al. (2017);30 Iran | Cases: 78 Controls: 50 |

Cases: infertile patients undergoing fertility treatment at local hospital and treatment center Controls: attended the same clinics as cases, but were partners of infertile females |

Cases: 31.7±3.4 ID: NR Controls: 33.4±6.0 |

1. SCL-90-R60

2. Cattle Inventory64 |

a. Psychological distress b. Anxiety |

NR | Cases had significantly higher scores on anxiety and paranoia than controls | 0.86 |

| Jamil et al. (2020);32 Pakistan | Cases: 45 Controls: 45 |

Cases: men presenting with primary infertility at outpatient clinics Controls: men attending same clinic for problems unrelated to fertility or as partners of infertile females |

Case: 33.2±7.3 ID: NR Controls: 31.5±4.8 |

1. SEAR Questionnaire65 | a. Sexual relationship b. Self-esteem c. Confidence d. Overall relationship |

NR | Cases scored significantly lower than controls on all domains of the SEAR | 0.91 |

IPAT: Institute of Personality and Ability Testing; s.d.: standard deviation; ID: infertility duration; NR: not reported; QA: quality assessment; O and G: obstetrics and gynecology; SF-36: Short Form Survey; QoL: quality of life; HAD-S: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90-revised; MCS: Mental Component Summary; SEAR: Self-Esteem and Relationship; MF: male factor

Table 2.

Study characteristics of cohort studies reporting psychological distress in men with male factor infertility compared to men in couples with other diagnoses

| Author (year); location | Study design | Male participants (n) | Cause of infertility (%) | Age and ID (year), mean±s.d. or median (range) | Psychosocial assessment instrument | Outcome measures | Timing of assessment | Main findings relevant to psychological distress in MF infertility | QA score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. (2001);33 Taiwan, China | Cross-sectional | 138 | MF: 38 FF: 31 MxF: 15 Unexplained: 15 |

Mean: 34.9 ID: NR |

1. Chinese version of the Infertility Questionnaire66

2. Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire67 3. Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire67 |

a. Self-esteem b. Blame/guilt c. Sexual impairment d. Marital satisfaction |

NR | No differences on any domain between MF, FF, MxF or unexplained | 0.64 |

| Holter et al. (2007);37 Sweden | Cross-sectional | 166 | MF: 39 FF/MxF/unexplained combined: 61 |

MF: 35.0±6.4 Other: 33.6±4.9 ID: NR |

1. Psychological General Well-being Index68 2. Author devised questionnaire | a. Psychological well-being b. QoL, effects of infertility, relationship, support |

2–4 weeks prior to treatment | MF reported less contact with friends and acquaintances than the other diagnoses groups combined No other differences | 0.86 |

| Peronace et al. (2007);41 Denmark | Longitudinal | 256 | Self-reported MF: 29.3 FF: 30.9 MxF: 8.2 Unexplained: 31.6 |

34.0±5.0 ID: 4.3±2.4 |

1. Fertility Problem Stress Inventory69

2. SF-3645 3. Stress Profile questionnaire70 4. Ways of Coping Checklist55 5. Four questions from the Danish Longitudinal Health Behaviour Study71 |

a. Fertility problem related stress b. Mental health c. Physical health d. Coping e. Social environment f. Openness to infertility |

T1: at first treatment T2: 12 months following T1 |

Mental health decreased between T1 and T2 but no difference between diagnostic groups or interaction Physical stress symptoms increased: no group difference or interaction Coping effort increased: no group difference or interaction Negative comments showed an interaction with the men in the unexplained group reporting more negative comments from social networks over time than female or MF |

0.86 |

| Dooley et al. (2014);31 Ireland | Cross-sectional Study 1: participants recruited through 2 fertility clinics Study 2: participants completed an online survey in answer to an advertisement on 10 fertility related websites |

Study 1: 111 Study 2: 55 |

Study 1 MF: 50 FF: 29.7 MxF: 22.5 remainder unreported Study 2 MF: 52.7 FF: 30.9 MxF: 16.3 remainder unreported |

Study 1: 37.4±5.1 ID: NR Study 2: 35.2±5.7 ID: NR |

1. GHQ-1272

2. Fertility Problem Inventory73 3. Dyadic Adjustment Scale53 4. Male Role Attitudes Scale74 5. RSES62 |

a. General mental well-being b. Fertility related stress c. Coping d. Attitudes towards masculinity e. Self-esteem |

Study 1: after a fertility appointment Study 2: online |

Study 1: MF reported less distress than FF Diagnosis type did not predict infertility distress Study 2: there were no significant difference in infertility distress between MF and FF Diagnosis type did not predict infertility distress |

0.59 |

| Patel et al. (2016);40 India | Cross-sectional | 300 | MF: 25.3 FF: 29.7 MxF: 30.3 Unexplained: 14.7 |

35 (24–54) ID: 1 (0–12) |

1. Clinical interview using ICD-1075

2. Psychological evaluation test for infertile couples76 |

a. Infertility specific related stress | After consultation with infertility specialist: referred for psychological evaluation | A diagnosis of MxF was 5 times more likely to elicit a high score of infertility distress than a diagnosis of FF An unexplained diagnosis was 4 times more likely to elicit a high score of infertility distress than FF |

0.84 |

| Valoriani et al. (2016);29 Italy | Cross-sectional | 309 | MF: 28.2 FF: 32 MxF: 11.7 Unexplained: 22.6 No examination: 5.5 |

37.2±5.0 ID: range 1–10 |

1. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale77

2. GHQ-1272 |

a. Depression b. General psychological and physical well-being |

After first consultation | No increased risk of depression based on diagnoses | 0.93 |

| Babore et al. (2017);23 Italy | Cross-sectional | 170 | Self-reported MF: 25.2 FF: 22.7 MxF 10.4 Unexpl-ained: 41.7 |

39.4±5.8 ID: NR |

1. Zung Depression Self-rating scale78 | a. Depression | Immediately after medical exam 69.4% were undergoing first treatment 30.6% had previous treatment(s) | MF had higher mean depression scores than other diagnoses, but this was not statistically significant | 0.75 |

| Goker et al. (2018);36 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 127 | MF: 6.3 FF: 29.1 MxF: 5.5 Unexplained: 59.1 |

31.4±5.9 ID: 3.8±3.3 |

1. Fertility QoL questionnaire44 | a. QoL | NR | There were no differences on any QoL domain between MF, FF, MxF or unexplained | 0.86 |

| Liu et al. (2021);26 China | Longitudinal | 247 | MF: 19.0 FF: 47.8 MxF: 25.1 Unexplained: 8.1 |

31.72±4.9 ID: 3.1±1.9 |

1. Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale79

2. Zung Self-rating Depression Scale78 |

a. Anxiety b. Depression |

T1: day one of treatment T2: hCG administration T3: 4 days following transfer |

Overall, proportionately more MF scored above the anxiety and depression cut-off compared to other diagnoses groups | 0.89 |

| Navid et al. (2017);27 Iran | Cross-sectional | 248 | MF: 39.5 FF: 30.6 MxF: 9.3 Unexplained: 20.6 |

33.3±5.7 ID: 4.8±3.5 |

1. HAD-S61

2. SWLS80 |

a. Anxiety b. Depression c. Life satisfaction |

NR | No difference in mean anxiety or depression scores between MF, FF, MxF, or unexplained Men in the mixed infertility group had significantly lower scores on life satisfaction than the other three groups |

0.89 |

| Asazawa et al. (2019);22 Japan | Cross-sectional | 321 | MF: 10.3 FF: 15.9 MxF: 2.1 Unexplained: 43.3% NYD: 18.4 |

37.9±5.2 ID: median 3 years and 1 month |

1. Fertility QoL survey44

2. Brief Scale of Social Support for Workers81 3. Jichi Medical School Social Support Scale82 4. Psychological distress – author devised questionnaire83 |

a. QoL b. Workplace support c. Spousal support d. Stress, anxiety, depressed mood |

After treatment | MF scored significantly lower on FertiQoL than unexplained and FF MxF and NYD both scored significantly lower on FertiQoL than FF MF scored significantly higher on the distress scale than FF and NYD Unexplained and MxF scored significantly higher on the distress scale than FF MF was a significant predictor of QoL along with spousal support and prolonged duration of infertility |

0.95 |

| Smith et al. (2009);38 USA | Cross-sectional | 357 | Perceived infertility MF: 12 FF: 47 MxF: 16 Unexplained: 25 |

36.9±5.5 ID: NR |

1. Author devised questionnaire38 | a. Personal impact b. Social impact c. Sexual impact d. Marital impact |

After treatment assessment | MF had higher sexual impact and personal impact score compared to FF after adjusting for confounders Unexplained infertility had higher social impact scores compared to FF, not significant after adjusting for confounders |

0.93 |

| Warchol-Biedermann (2019)43 and (2021);39 Poland | Longitudinal | 255 | MF: 29.8 FF: 31.4 MxF: 30.6 Unexplained: 8.2 |

30.2±4.3 ID: 1.2±0.3 |

1. GHQ-2872

2. Fertility QoL Questionnaire44 |

a. Emotional distress b. Psychiatric morbidity c. Fertility related QoL |

T1: before initial fertility evaluation T2: 2–3 months after diagnostic disclosure T3/4: before follow-up appointments |

Prevalence of distress in MF 9.2% at T1, 59.2% at T2, 49.2% at T3 and 34.6% at T4 Prevalence of distress in FF 13.7% at T1, 21.5% at T2, 42.6% at T3, and 34.4% at T4 Prevalence of distress in MxF 11.5% at T1, 67.5% at T2, 50.7% at T3 and 16.3% at T4 Prevalence of distress in Unexplained 4.7% at T1, 9.5% at T2, 15.7% at T3 and 0% at T4 QoL reduces from T1 to T2 and then remains stable in MF and MxF QoL remains stable between T1 and T2 in FF but then decreases at T3 QoL does not change over time in unexplained At T1, FF reported the lowest QoL compared to all other groups. MxF had significantly poorer QoL compared to MF and unexplained At T2, MF, FF and MxF reported lower QoL than unexplained. MxF was also significantly lower than FF At T3, MF, FF and MxF scored significantly lower QoL than unexplained At T4, FF and MxF scored lower QoL than unexplained. There was no statistical difference between MF and unexplained |

2019: 0.73 2021: 0.68 |

| Sejbaek et al. (2020);28 Denmark | Register-based study. Data linkage | 446 | MF: 33.7 FF: 42.2 MxF: 8.4 Unexplained: 15.7 |

36.4±6.7 ID: NR |

1. Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register84 | a. Unipolar depression | NA | Men with their first depression prior to ART were more likely to be diagnosed with MF than men with their first depression diagnosis after ART MF did not increase the risk of depression after ART treatment |

0.82 |

s.d.: standard deviation; MF: male factor; FF: female factor; MxF: mixed factor (both parties have fertility concerns); ID: infertility duration; NR: not reported; QoL: quality of life; ART: assisted reproductive technology; QA: quality assessment; NYD: not yet determined; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale; SF-36: Short Form Survey; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; HAD-S: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NA: Not available; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; hCG: human chorionic gonadotropin

Psychological distress

The included studies reported on seven different aspects of psychological distress: depression (n = 9),21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 anxiety (n = 7),21,22,24,25,26,27,30 self-esteem (n = 5),21,24,31,32,33 quality of life or aspects of quality of life such as marital or sexual relationship (n = 11),22,24,27,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 fertility-related stress (n = 4),22,31,40,41 general psychological distress or well-being (n = 7),29,30,31,37,41,42,43 and psychiatric conditions (n = 2).21,43

Study setting

The studies were conducted in 14 different countries: three in Iran,27,30,42 two each in Denmark,28,41 Italy,23,29 Poland,25,34,39,43 Tunisia,21,35 and China,26,33 and one each in Canada,24 India,40 Ireland,31 Japan,22 Pakistan,32 Sweden,37 Turkey,36 and the USA.38 Some studies have multiple publications.

Study design and data sources

Data for the 23 publications originated from 21 studies. The publications by Drosdzol and Skrsypulec25,34 and by Worchol-Biedermann39,43 report on different outcomes from the same study. It appears that the publications of El Kissi et al.35 and Amamou et al.21 are also based on the same study; however, as they are not cross-referenced and contain different methodological information, they have been reported here as separate studies. Eight publications were based on a case/control design (Table 1),21,24,25,30,32,34,35,42 ten employed a cross-sectional design,22,23,27,29,31,33,36,37,38,40 four were longitudinal,26,39,41,43 and one was based on a data linkage study28 (Table 2). Except for the data linkage study, all used self-report questionnaires to obtain data. Most studies (n = 15/23) used validated assessment tools. Two studies used study-specific measures of emotional distress and two used both validated tools and study-specific measures.

Participants and recruitment

In all but three studies, participants were recruited from fertility clinics, either in public hospitals or private clinics. One study sourced participants from 10 fertility-related websites.31 Data for the linkage study were obtained from the Danish in vitro fertilization (IVF) register and Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register.28 The description of the fertility status of the controls in case–control studies varied. In one study, men whose partner was currently pregnant24 and in another male parents of children attending a vaccination clinic with no history of infertility35 were presumed to be fertile. Controls from four other case–control studies were men whose fertility status was unknown as they were either attending a clinic for matters unrelated to infertility25,32,34 or were partners of women with an infertility diagnosis.30,32,42 Although these men were described as fertile, objective markers of fertility were not provided. One publication did not report the source of the control group, however having one child and no history of infertility was listed as an inclusion criterion.21

The number of participants ranged from 90 to 446. The total number of men categorized as infertile across all studies was 4057. The mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) age of participants, where reported, was 34.4 ± 5.0 years. Eleven studies reported the duration of infertility. Of these, nine reported the mean (pooled mean ± s.d.: 4.2±2.4 years),21,24,26,27,36,39,41,42,43 two reported the range (1–10 years29 and 0–12 years40), and one reported the median duration of infertility (3 years and 1 month22). The percentage of men diagnosed with male factor infertility ranged from 6.3% to 52.7%. The pooled mean percentages for each infertility diagnostic category were: 29.2% (male factor), 32.2% (female factor), 15.1% (mixed factor), and 25.5% (unexplained). These figures do not add to 100% as some studies had additional categories22,29,31 or combined groups.37

Study quality

Concordance in the assessment of study quality between the authors was high, with a mean difference in scores of 0.06 (range: 0–0.27). Overall, the included studies were of moderate-to-high quality as measured by QualSyst18 (Table 1 and 2). As none of the studies included an intervention, the three questions relating to this were removed. Of the remaining 11 questions, the mean score for all studies was 0.79 (range: 0.36–0.95). The criterion least addressed was controlling for confounders. Eleven of the 23 studies made no attempt to control for confounders, four made a partial attempt, and eight included confounders in their analyses.

Main findings

Eight case–control studies reported psychological distress in infertile men compared to men described as fertile (Table 1). Four assessed depression and/or anxiety,21,24,25,30 three examined quality of life,22,34,35 and three reported on general psychological distress21,30,42 and self-esteem,21,24,32 respectively.

Fifteen cohort studies reported differences in psychological distress between men with male factor infertility and men in couples with other infertility diagnoses (Table 2). Five examined the symptoms of depression and/or anxiety symptoms,22,23,26,27,29 eight reported on quality of life,22,27,33,36,37,38,39,44 five on general psychological distress,29,31,37,41,43 three on infertility-related stress,22,31,41 and one on self-esteem.31

Depression and anxiety

Compared to controls, men with diagnosed infertility were found to have significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety symptomology.21,25,30 The one study that did not show a difference was limited by a small sample size.24 Having a male infertility diagnosis did not appear to increase the risk of depression or anxiety over and above the risk associated with other causes of infertility, with four22,23,27,29 of the five cohort studies reporting no difference between diagnostic groups. In the study that did find a difference,26 34% of men diagnosed with male infertility experienced depressive symptoms compared to 8.5%, 8.1%, and 15% of men with diagnoses of female factor, mixed factor, and unknown factors, respectively.

Quality of life (QoL)

Two case–control studies34,35 assessed the quality of life via the Short Form Survey (SF-36).45 Lower scores in the vitality domain, indicative of poorer quality of life in this area, were reported by infertile men than controls in both studies. Results for other domains were conflicting. Drozdzol and Skrzypulec34 found no differences in any of the other QoL domains, while El Kissi et al.35 found infertile men scored lower (i.e., poorer QoL) than controls on the domains of social functioning, role-emotional, and the overall summary domain of mental health.

Of the seven cohort studies examining QoL, four studies27,37,38,39 reported poorer QoL in at least one domain in men with male infertility compared to other infertility diagnoses. Asazawa et al.22 assessed QoL via the Fertility Quality of Life Scale44 and found that men with male factor infertility reported poorer quality of life than men with other diagnoses, in particular those with female factor or unexplained infertility. Holter et al.37 asked men to compare their ideal life to how their life was currently and found that men diagnosed with male factor infertility had a greater disconnect between ideal versus real life in the area of contact with friends and acquaintances than men in couples with other diagnoses. Navid et al.27 found that men in couples with mixed factor infertility had reported poorer satisfaction with life than those in couples of other diagnoses. Smith et al.38 found that the following areas of life were impacted by male factor infertility: sexual, personal, and social relationships. Warchol-Biedermann39 reported that men with male factor infertility had better QoL than men in couples with female or mixed factor infertility before diagnosis; however, after diagnosis, there was no difference between these groups. Goker et al.36 and Lee et al.33 reported no differences between diagnostic groups.

General psychological distress and psychotic symptoms

Infertile men were reported to have greater paranoia,30 psychotic symptoms,21 and reduced psychosocial development,21,42 when compared to men whose fertility status was unknown. Three of the five cohort studies reported no difference in psychological distress between diagnostic groups.29,37,41 In their clinical sample, Dooley et al.31 found that men with diagnosed infertility themselves reported less distress than men whose partners were infertile. No differences were found between diagnostic groups in their online sample. Warchol-Biedermann43 reported that the proportion of men at risk of psychiatric morbidity following diagnosis increased by 50% in men with male factor and 56% in men in a couple with mixed factor, compared to an increase of 8% and 5% in men in couples diagnosed with female factor and unexplained infertility, respectively. Between-group comparisons were not statistically analyzed.

Self-esteem

Infertile men reported lower self-esteem score than men where fertility status was unknown in two21,32 of three case–control studies.21,24,32 As with depression and anxiety above, no difference was found in Dhillon et al.24 potentially due to the small sample size. Of the cohort studies, Lee et al.33 reported no difference in self-esteem scores between diagnostic groups. While self-esteem was measured in Dooley et al.,31 it was used as a predictor of distress, rather than an outcome variable. In that study, lower self-esteem was significantly related to higher infertility distress in both the clinical and online samples.

Infertility-related stress

Four of the cohort studies assessed infertility-related stress.22,31,40,41 Results varied depending on the assessment method used. Patel et al.40 used clinical interviews and found significantly higher infertility-related stress in men with male factor infertility than in men in couples with other infertility diagnoses.40 The two studies that used questionnaires to assess fertility-related stress did not find a difference.22,31 In their longitudinal study, Peronace et al.41 found that social and marital stress increased over time in all diagnostic groups, with no difference between the groups or interaction between diagnosis and time.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study suggest that a diagnosis of infertility, regardless of whether the cause of the infertility is male or female related, adversely affects the mental health of men. Compared to men who have been described as fertile, men with male factor infertility have more symptoms of depression, anxiety and general psychological distress, worse quality of life in some areas, and lower self-esteem. However, when men with male factor infertility were compared to men in couples with female factor, mixed factor, or unexplained infertility, there were more similarities than differences. This suggests that the experience of infertility, irrespective of its cause, negatively affects men’s psychological well-being.

There are some limitations to this study. Due to the lack of consistent assessment tools used across the studies, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis. Between-study comparisons were difficult due to inconsistent definitions of the infertility status of cases (e.g., medically assessed versus self-perception of infertility status) and the fertility status of controls (e.g., men in currently pregnant couples versus male partners of women undergoing routine gynecological examinations). The use of generalized terms of psychological distress and varying recruitment sources also prevented direct comparisons. As such, caution must be taken when interpreting the findings of this study. While only reviewing articles in English can be considered a limitation, it must be noted that the majority of studies were conducted in countries where English was not the first language. In addition, many of the studies had been conducted in traditionally strong patriarchal societies (e.g., Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey). Although there is a potential that men’s cultural and religious backgrounds may create a belief bias around masculinity and infertility, the outcomes of the studies included in this study suggest that infertility distress is not culture-specific.

Although the methodological quality of the studies was rated as moderate to high, there are a number of study limitations to consider, including small sample sizes, the use of nonvalidated study-specific assessment tools, and lack of control of confounders, particularly the timing of the psychological assessments. The longitudinal studies included in this study26,39,41,43 clearly show that psychological distress reduces over the treatment journey, with the highest level of distress occurring just after the diagnosis and prior to starting treatment. Thus, any differences observed in case–control studies would likely differ in magnitude depending on when in the treatment journey the assessment took place.

In addition, these studies cannot be presumed to be addressing the full psychological profile of men experiencing infertility. Qualitative studies suggest that men might be more likely to express anger, frustration, guilt, disempowerment, or feelings of disconnection, rather than depression or anxiety.8 Although the terms “anger” and “guilt” were used as search terms for this study, few of the identified studies examined these concepts. In those that did, there was either no difference between the groups24,33 or the results were not presented.42 Interviews and discussions may be more likely to illicit an emotional response that more closely approximates how men are genuinely feeling.8 The contrary results in infertility-related stress between Patel et al.,40 who conducted interviews, and three studies22,31,41 that employed questionnaires to gather data, lend some support to this. A more comprehensive review that includes qualitative studies is warranted to fully understand the breadth of emotions experienced by men undergoing ART and inform patient-centered care.

It may also be that men are reluctant to discuss their psychological distress as a way of protecting their partner. In qualitative studies, men report the need to “be strong”, with concern for their partner’s emotional and mental well-being taking precedence over their own feelings of despair and grief.8,13,46 Standardized assessment tools, such as those used in the studies of this systematic analysis, may not be sensitive enough to detect the nuances of psychological distress in men experiencing infertility. Interviews and discussions with medical staff may be more likely to reveal men’s true emotional responses to infertility, as is suggested by the different results when using clinical interview40 versus self-reported questionnaires.22,31

Despite the limitations, these findings emphasize the need for ART providers to consider men as individuals with their own unique support needs and implement patient-centered care that meets their needs, which may be different to women’s.47 Aside from their partner, the most common place men seek support is from the clinic or medical staff.7 Yet, some studies are showing that men continue to feel disenfranchised in their encounters with ART clinic staff. A survey of 210 men undergoing fertility treatment in Denmark6 revealed that 63% of men reported that the medical staff communicated predominantly with their female partner, and only 10% agreed that the medical staff gave them the opportunity to discuss their experiences of infertility. Bringing them into the conversation regarding mental well-being during the ART process might validate and normalize their feelings as well as acknowledge they play an active role in the treatment process.48

This analysis provides further evidence to the growing literature that calls for the systematic implementation of patient-centered care in ART settings. In particular, a model of care that caters for the unique needs of all men, irrespective of their personal infertility diagnosis, could potentially mitigate the psychological distress felt by these men.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SNB conceived the study, conducted the database searches and first screening of manuscripts, contributed in assessing the quality of the included manuscripts, extracted the data, and drafted the manuscript. JH provided the resources and supervision, contributed in the quality assessment of included manuscripts, and reviewed drafts of this manuscript. KH designed the methodology, contributed in the quality assessment of included manuscripts, and reviewed drafts of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dancet EA, D’Hooghe TM, van der Veen F, Bossuyt P, Sermeus W, et al. “Patient-centered fertility treatment”: what is required? Fertil Steril. 2014;101:924–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duthie EA, Cooper A, Davis JB, Schoyer KD, Sandlow J, et al. A conceptual framework for patient-centered fertility treatment. Reprod Health. 2017;14:114. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0375-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gameiro S, Boivin J, Dancet E, de Klerk C, Emery M, et al. ESHRE guideline: routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction-a guide for fertility staff. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2476–85. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2001. p. 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leyser-Whalen O, Bombach B, Mahmoud S, Greil AL. From generalist to specialist: a qualitative study of the perceptions of infertility patients. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2022;14:204–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikkelsen AT, Madsen SA, Humaidan P. Psychological aspects of male fertility treatment. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:1977–86. doi: 10.1111/jan.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammarberg K, Baker HW, Fisher JR. Men's experiences of infertility and infertility treatment 5 years after diagnosis of male factor infertility: a retrospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2815–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna E, Gough B. Experiencing male infertility: a review of the qualitative research literature. SAGE Open. 2015;5:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun H, Gong TT, Jiang YT, Zhang S, Zhao YH, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:10952–91. doi: 10.18632/aging.102497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffy JM, Adamson GD, Benson E, Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S, et al. Top 10 priorities for future infertility research: an international consensus development study. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:180–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivius C, Friden B, Borg G, Bergh C. Why do couples discontinue in vitro fertilization treatment? A cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:258–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borghi L, Leone D, Poli S, Becattini C, Chelo E, et al. Patient-centered communication, patient satisfaction, and retention in care in assisted reproductive technology visits. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:1135–42. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik SH, Coulson NS. Computer-mediated infertility support groups: an exploratory study of online experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connolly KJ, Edelmann RJ, Cooke ID, Robson J. The impact of infertility on psychological functioning. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:459–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90006-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kedem P, Mikulincer M, Nathanson YE, Bartoov B. Psychological aspects of male infertility. Br J Med Psychol. 1990;63:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1990.tb02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nachtigall RD, Becker G, Wozny M. The effects of gender-specific diagnosis on men's and women's response to infertility. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Alberta: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumbak B, Atak IE, Attar R, Yildirim G, Yesildaglar N, et al. Psychologic influence of male factor infertility on men who are undergoing assisted reproductive treatment: a preliminary study in a Turkish population. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roopnarinesingh R, El-Hantati T, Keane D, Harrison R. An assessment of mood in males attending an infertility clinic. Ir Med J. 2004;97:310–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amamou B, El Kissi Y, Hidar S, Bannour S, Idrissi KA, et al. Psychological characteristics of Tunisian infertile men: a research note. Men Masc. 2013;16:579–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asazawa K, Jitsuzaki M, Mori A, Ichikawa T, Shinozaki K, et al. Quality-of-life predictors for men undergoing infertility treatment in Japan. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2019;16:329–41. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babore A, Stuppia L, Trumello C, Candelori C, Antonucci I. Male factor infertility and lack of openness about infertility as risk factors for depressive symptoms in males undergoing assisted reproductive technology treatment in Italy. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:1041–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon R, Cumming CE, Cumming DC. Psychological well-being and coping patterns in infertile men. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:702–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V. Depression and anxiety among polish infertile couples–an evaluative prevalence study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;30:11–20. doi: 10.1080/01674820902830276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu YF, Fu Z, Chen SW, He XP, Fan LY. The analysis of anxiety and depression in different stages of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer in couples in China. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:649–57. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S287198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navid B, Mohammadi M, Vesali S, Mohajeri M, Omani Samani R. Correlation of the etiology of infertility with life satisfaction and mood disorders in couples who undergo assisted reproductive technologies. Int J Fertil Steril. 2017;11:205–10. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2017.4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sejbaek CS, Pinborg A, Hageman I, Sorensen AM, Koert E, et al. Depression among men in art treatment: a register-based national cohort study. Hum Reprod Open 2020. 2020:hoaa019. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoaa019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valoriani V, Lotti F, Lari D, Miccinesi G, Vaiani S, et al. Differences in psychophysical well-being and signs of depression in couples undergoing their first consultation for assisted reproduction technology (ART): an Italian pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karimzadeh M, Salsabili N, Akbari Asbagh F, Teymouri R, Pourmand G, et al. Psychological disorders among Iranian infertile couples undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) Iran J Public Health. 2017;46:333–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dooley M, Dineen T, Sarma K, Nolan A. The psychological impact of infertility and fertility treatment on the male partner. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2014;17:203–9. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.942390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamil S, Shoaib M, Aziz W, Ather MH. Does male factor infertility impact on self-esteem and sexual relationship? Andrologia. 2020;52:e13460. doi: 10.1111/and.13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee TY, Sun GH, Chao SC. The effect of an infertility diagnosis on the distress, marital and sexual satisfaction between husbands and wives in Taiwan. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1762–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.8.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V. Quality of life and sexual functioning of polish infertile couples. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13:271–81. doi: 10.1080/13625180802049187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Kissi Y, Amamou B, Hidar S, Ayoubi Idrissi K, Khairi H, et al. Quality of life of infertile Tunisian couples and differences according to gender. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;125:134–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goker A, Yanikkerem E, Birge O, Kuscu NK. Quality of life in Turkish infertile couples and related factors. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2018;21:195–203. doi: 10.1080/14647273.2017.1322223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holter H, Anderheim L, Bergh C, Moller A. The psychological influence of gender infertility diagnoses among men about to start IVF or ICSI treatment using their own sperm. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2559–65. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith JF, Walsh TJ, Shindel AW, Turek PJ, Wing H, et al. Sexual, marital, and social impact of a man's perceived infertility diagnosis. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2505–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warchol-Biedermann K. The etiology of infertility affects fertility quality of life of males undergoing fertility workup and treatment. Am J Mens Health. 2021;15:1557988320982167. doi: 10.1177/1557988320982167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel A, Sharma PS, Narayan P, Nair BV, Narayanakurup D, et al. Distress in infertile males in Manipal-India: a clinic based study. J Reprod Infertil. 2016;17:213–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peronace LA, Boivin J, Schmidt L. Patterns of suffering and social interactions in infertile men: 12 months after unsuccessful treatment. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;28:105–14. doi: 10.1080/01674820701410049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akhondi MM, Binaafar S, Ardakani ZB, Kamali K, Kosari H, et al. Aspects of psychosocial development in infertile versus fertile men. J Reprod Infertil. 2013;14:90–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warchol-Biedermann K. The risk of psychiatric morbidity and course of distress in males undergoing infertility evaluation is affected by their factor of infertility. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13:1557988318823904. doi: 10.1177/1557988318823904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boivin J, Takefman J, Braverman A. The Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQOL) tool: development and general psychometric properties. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2084–91. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: New England Medical Centre, the Health Institute; 1993. p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dolan A, Lomas T, Ghobara T, Hartshorne G. 'It's like taking a bit of masculinity away from you': towards a theoretical understanding of men's experiences of infertility. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39:878–92. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molgora S, Baldini MP, Tamanza G, Somigliana E, Saita E. Individual and relational well-being at the start of an art treatment: a focus on partners'gender differences. Front Psychol. 2020;11:2027. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harlow AF, Zheng A, Nordberg J, Hatch EE, Ransbotham S, et al. A qualitative study of factors influencing male participation in fertility research. Reprod Health. 2020;17:186. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-01046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krug S, Laughlin J. Handbook for the IPAT Depression Scale. Champaign: Institute of Personality and Ability Testing; 1976. p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the State-Trait Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists'Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spielberger C. State-trait Anger-Expression Inventory. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hudson W. The Clinical Measurement Package: A Field Manual. Chicago: Dorsey; 1982. p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spanier G. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCubbin H, Patterson J, Wilson L. Family inventory of life events and changes. St. Paul: Medical Education and Research; 1981. p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3130–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, et al. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beck A, Steer R. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Derogatis L. SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. 3rd ed. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson; 1994. p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Revised edition. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press; 1989. p. 347. [Google Scholar]

- 63.El Kissi Y, Romdhane AB, Hidar S, Bannour S, Ayoubi Idrissi K, et al. General psychopathology, anxiety, depression and self-esteem in couples undergoing infertility treatment: a comparative study between men and women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;167:185–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alvandi A. Validity and Reliability of Cattle Inventory for Iranians. Tehran: Tehran University; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cappelleri JC, Althof SE, Siegel RL, Shpilsky A, Bell SS, et al. Development and validation of the self-esteem and relationship (SEAR) questionnaire in erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:30–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee SH, Kau BJ, Lee MC, Lee MS. [Psychosocial responses of infertile couples attending an assisted reproduction program. J Formo Med Assoc. 1995;94(Suppl 1):S26–33. [Article in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee TY, Sun GH. Psychosocial response of Chinese infertile husbands and wives. Arch Androl. 2000;45:143–8. doi: 10.1080/01485010050193913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dupuy HJ. The psychological general well-being (PGWB) index. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CD, Elinson J, editors. Assessment of Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies. New York: Le Jacq Publishing; 1984. pp. 170–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abbey A, Andrews F, Halrnan L. Gender's role in responses to infertility. Psych Women Quart. 1991;15:295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sven Setterling G. The stress profile: a psychosocial approach to measuring stress. Stress Med. 1995;11:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Due P, Holstein B, Lund R, Modvig J, Avlund K. Social relations: network, support and relational strain. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:661–73. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goldberg D. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Oxford: NFER-Nelson; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Newton CR, Sherrard W, Glavac I. The fertility problem inventory: measuring perceived infertility-related stress. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:54–62. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Masculinity ideology: it's impact on adolescent males'heterosexual relationships. J Soc Issues. 1993;49:11–29. [Google Scholar]

- 75.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. pp. 65–135. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Franco JG, Jr, Razera Baruffi RL, Mauri AL, Petersen CG, Felipe V, et al. Psychological evaluation test for infertile couples. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2002;19:269–73. doi: 10.1023/A:1015706829102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maroufizadeh S, Ghaheri A, Omani Samani R, Ezabadi Z. Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in Iranian infertile women. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14:57–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mori K, Miura K. Development of the brief scale of social support for workers and its validity and reliability. Annu Bull Inst Psychol Stud Showa Womens Univ. 2007;9:74–88. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsutsumi A, Kayaba K, Ishikawa S, Kario K, Matsuo H, et al. [Jichi Medical School Social Support Scale (JMS-SSS): revision and tests for validity and reliability. Jpn J Public Health. 2000;47:866–78. [Article in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Asazawa K, Mori A. Development of a partnership causal model for couples undergoing fertility treatment. J Japan Acad Nurs Sci. 2015;12:208–21. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:54–7. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]