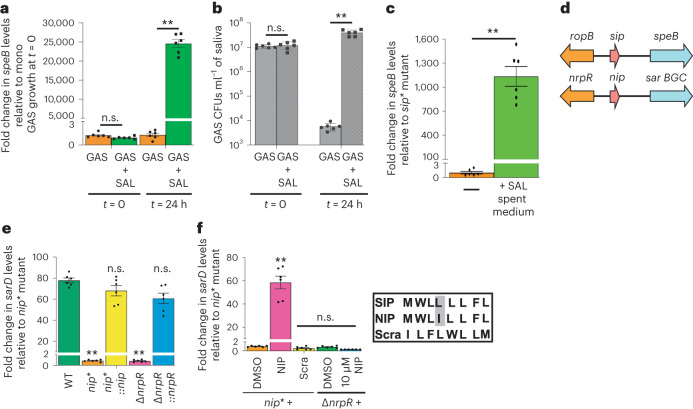

Fig. 3. Mechanism of pathogen evasion of probiotic cytotoxicity.

a,b, GAS upregulate speB expression (a) during growth with SAL that promotes GAS survival (b) in human saliva. Samples were collected at the indicated timepoints. speB expression (a) and GAS burden (b) were assessed by qRT–PCR and CFU analyses, respectively. c, GAS sip* mutant with a substitution of stop codon at sip start codon does not produce SIP and requires exogenous induction to activate speB expression. Incubation of sip* mutant with the cell-free culture supernatant obtained from SAL growth activates speB expression in GAS sip* mutant. d, Schematics showing the similarities between speB-activating ropB-sip quorum sensing system in GAS and the nrpR-nip signalling system in SAL identified in this study. e, The NIP and its cognate receptor NrpR controls the expression of sar BGC. Indicated strains were grown to late-exponential phase of growth and sarD transcript levels were measured by qRT–PCR. f, Synthetic peptide containing the amino acid sequence of NIP in native order encodes an intercellular peptide signal and activates sarD expression in SAL nip* mutant. In a–c, e and f, bars represent mean ± s.e.m. and statistical significance relative to reference was assessed by Mann–Whitney test. **P < 0.01; n.s., not significant. In e, sarD transcript levels in WT SAL growth were used as a reference, whereas in f, unsupplemented nip* mutant growth was used as a reference.