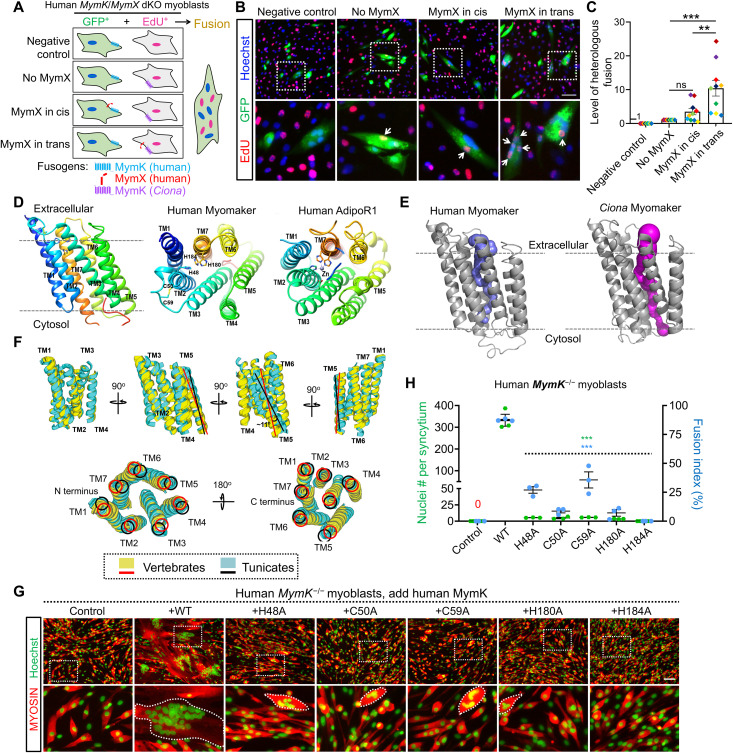

Fig. 5. Evolutionarily distinct Mymk proteins reveal mechanistic insights into structure function and synergy.

(A) Schematic of experiment design. Note that the basal level of myoblast fusion requires MymK to be present in both cells, while the expression of vertebrate MymX can only boost vertebrate MymK (e.g., human) but not nonvertebrate (e.g., Ciona) MymK activity. The natural uncoupling between MymX synergy and fusogenicity observed in tunicate MymK permits the test of vertebrate MymX/MymK synergy using cell mixing cultures. dKO, double knockout. (B) Representative fluorescence images of human myoblasts after mixing culture as illustrated in (A). Arrows point to the EdU+ nuclei inside GFP+ cells formed from fusion. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Measurement of heterologous fusion by counting EdU+ nuclei inside GFP+ syncytia. Data were normalized to the “no MymX” group. Data from the same replicate were highlighted in the same color. N = 10. **P < 0.01; ns, not significant. (D) Ribbon representation of the predicted human MymK structure. TM, transmembrane helix. The conserved histidine and cysteine residues on human MymK model are highlighted. Zinc-binding motif of adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1; PDB ID: 6KRZ) was shown on the right. (E) Side views of the predicted cavities inside MymK proteins. (F) Superimpositions of the overall structural models for MymK proteins from vertebrates (human, mouse, zebrafish, and elephant shark) and tunicates (Phallusia, Ciona, and Styela). The orientations of TM5 show obvious shifts between the two taxonomic groups. (G) Myosin immunostaining of human MymK −/− myoblasts that revealed the fusogenic activity of human MymK mutants. Cells were differentiated for 4 days. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) Measurement of myoblast fusion in (G) after myogenic differentiation and compared to WT expression group. Data are means ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.