Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are persistent organic pollutants that may contaminate various water sources and pose serious dangers to human health and the environment. Due to their capacity for size-based separation, nanofiltration membranes have become efficient instruments for PAH removal. However, issues such as membrane fouling and ineffective rejection still exist. To improve PAH rejection while reducing fouling problems, this work created a new gradient cross-linking poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) nanofiltration membrane. The gradient cross-linking technique enhanced the rejection performance and antifouling characteristics of the membrane. The results demonstrated that the highest membrane flow was achieved at a 0.15% SDS-PVP membrane. There is a trade-off between membrane flux and salt rejection since salt rejection increases with SDS owing to the growth of big pores. The membrane flux was reduced for the 0.25% SDS-PVP membrane owing to poor SDS dispersion. The prepared membrane showed enhanced removal efficiencies for the removal of the PAH compounds. The PVP membrane has the potential to be used in several water treatment applications, improving water quality, and preserving the environment.

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of organic compounds composed of fused aromatic rings.1 They are ubiquitously found in the environment, originating from natural sources such as forest fires and volcanic eruptions, as well as anthropogenic activities like incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, industrial processes, and waste disposal.2 The widespread presence of PAHs in air, soil, and water has raised significant environmental and health concerns due to their toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties.3,4

Water contamination by PAHs has become a pressing global issue, demanding effective and sustainable removal technologies to safeguard aquatic ecosystems and human well-being.4 Traditional water treatment methods, such as activated carbon adsorption and chemical precipitation, have limitations in handling PAHs due to their low solubility and resistance to degradation.5 Consequently, innovative approaches are being explored to address the challenges associated with PAH removal from water sources.6

Among remediation methods, commonly intentional approaches for removing pollutants through wastewater are natural remediation or enhanced biodegradation.7,8 Metabolism (direct degradation using microorganisms) or co-metabolism (indirect degradation) by the natural presence of microorganisms in polluted water can degrade PAHs effectively.8,9 Due to their low cost, different kinds of porous membranes (cellulosic fiber and thin-film membranes) have been studied,10 which is a simple approach for the adequate adsorptive rejection of PAHs from the aqueous environment.11 The adsorption of PAHs onto porous and trigged carbon from different means, such as the gaseous phase, the aquatic environment, and oil, has been reported by many researchers.12,13 Nonpolar adsorptive membranes (i.e., lower oxygen content) have resulted in being more adequate for PAH adsorption by reducing the affinity and accessibility of PAHs to the inner pore structure by the composition of hydration clusters. However, the adsorption is strongly based on pore size distribution, especially thin micropores.13,14

A thin-film adsorptive (TFA) membrane is widely used to eliminate PAHs from wastewater and, when applied in static and dynamic adsorption modes, could stand operating parameters such as transmembrane pressure and stirring.15 At high porosity in the aqueous phase, the mechanical stability of the adsorptive membrane is reduced.16 To overcome this drawback, it is necessary to synthesize adsorptive membranes with reinforced structures to gain enough mechanical strength and void capacity advantages for adsorption.17,18 Thus, the TFA membrane has real advantages of its support layer along with adapted skin tactfully and is synthesized by different polymers such as polyamide (PA), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), cellulosic acetate (CA), and polysulfone (PSF) supported with organic and inorganic functionalized with various cross-linkers.18 However, due to the high selectivity and high flux, TFA is a pressing need for cost-efficient PAHs removal from wastewater.19

Polysulfone is one of the most prevalent polymers for membrane casting due to its outstanding mechanical, high thermal, and excellent chemical stability with relatively low cost and suitable flux.20−22 It is hydrophobic, but hydrophilicity can be enhanced by adding inorganic filler into a membrane with a wide aperture adjustment range.23,21 Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) is a nonconducting, biocompatible, and nontoxic polymer with an excellent performing agent and is known as one of the most used membrane additives.24−26 It is soluble in polar solvents with good adhesion and applied as a morphology controller.25,27,28 It also enhanced the viscosity of the casting solution and leached out into the water during membrane synthesis.29 Due to being hydrophilic, it enhances the antifouling properties of polymer membranes.30,31 Due to its good performance, epichlorohydrin (ECH) is a cationic water-soluble additive that provides permanent wet strength in alkaline conditions. Due to its appealing property of repelling water or moisture, it is used as a coating material where moisture resistance is crucial.32

In the literature, PVP and cross-linkers are combined straight before being coated on the support membrane. Due to the as-coated membrane’s limited permeability and selectivity, several researchers have created cross-linked PVP membranes for RO and NF applications. Still, none of these have been commercially successful because a thick PVP layer formed.33 Despite the cross-linker chemistry, its connections to the resulting NF Performance have been extensively researched. Still, few tactics have been created to engineer the cross-linked PVP’s substructures layer.34 Adding ECH as a polymer additive on the PVP surface is a fundamental approach to enhance the hydrophobicity of the membrane and reduce fouling, resulting in increased membrane permeability. Coating and surface modification aim to protect the underlying substrate from chemical attack, mechanical wear, and hydrophilization.

This study aims to explore SDS as a novel material in the PVP membrane for PAHs removal. An efficient nanofiltration could be achieved by gradient cross-linking inside the PVP rejection layer: (1) formed a gradient cross-linked top layer into a fully cross-linked bottom PVP layer by delayed diffusion method, (2) adopted surface coating method to impregnate cross-linker to stimulate surface activation, (3) anchored cross-linker in the pores of support membrane to reduce the defects, and (4) a nascent rigid cross-link structure was formed by use of phthalic acid cross-linker.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Polysulfone (PSF) (weight-averaged molecular weight (Mw) ∼ 35 kDa) and ECH (M.W = 92.52 g/mol, >98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) (Mw 10 kDa), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, M.W = 98.079 g/mol, =95–98%), SDS (C12H25NaO4S, M.W = 288.38 g/mol, ∼90%), H2O2 (M.W = 34.01 g/mol, =35%), and KMnO4 (M.W = 158.034 g/mol) was obtained from Merck, Germany, whereas N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), alcohol (C2H5OH, M.W = 46.07 g/mol, =99.08%), and phthalic acid (C8H6O4, M.W = 166.14 g/mol, =99%) were purchased from RCI Labscan and BDH, England, respectively. HCl (M.W = 36.46 g/mol, =36.5–38%) and NaNO3 (M.W = 84.99 g/mol) were purchased from J.T. Baker and Panreac, respectively. NaOH, hyperbranched polyethylenimine (HPEI), and all other chemicals were analytically graded and used as received.

2.2. Functionalization with Epichlorohydrin

Epichlorohydrin (15 mL) was added to produce a cationic group over the PVP membrane under stirring for 3 h and act as a cross-linker. The solution was neutralized by adding HCl (6 M) and was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. The final product ECH functionalized was obtained by rinsing 4–5 times with distilled water.

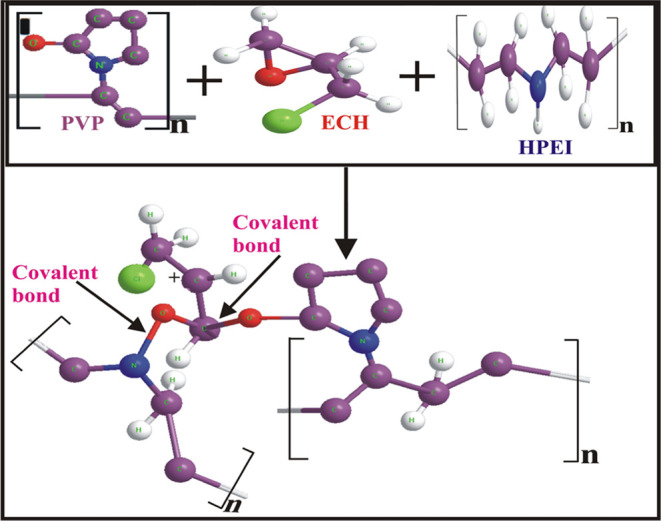

2.3. Synthesis of ECH-HPEI

A dispersed solution of ECH (approximately 3 g) was meticulously prepared in distilled water. This solution was distinctive due to the presence of hydrophilic groups, facilitating the dispersion process. The solution was subjected to sonication for 20 min to enhance the dispersion further, ensuring that the ECH was uniformly distributed within the water medium. The next step involved the addition of a NaOH solution with a concentration of 3 M to the mixture. This addition was carried out precisely to achieve a target pH level of 10, which is a critical parameter for the ensuing reaction. Subsequently, 20 mL of HPEI measuring 20 mL was introduced into the dispersed ECH solution. This addition was carried out under continuous stirring to maintain homogeneity and was conducted at 60 °C to promote the reaction. Following this, a centrifugation step was performed, lasting 10 min and reaching a speed of 14,000 rpm. This centrifugation separated the newly formed product from any unreacted or impure substances. To ensure the highest purity of the final product, it underwent a thorough rinsing process with distilled water, repeated 4 to 5 times to remove any residual impurities or byproducts. As a result of these precise and controlled reactions and purification steps, the final product, PVP-ECH-HPEI, was successfully obtained, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PVP-ECH-HPEI nanocomposite preparation process.

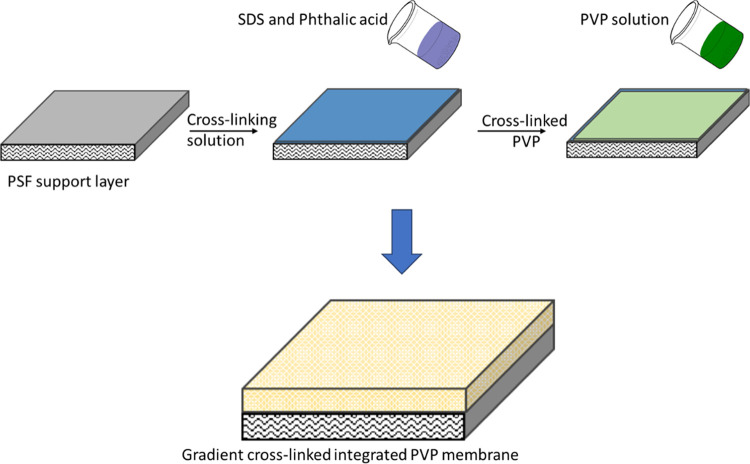

2.4. Synthesis of Gradient Cross-Linkage PVP Membrane

PSF (1 g) was blended in NMP (20 mL) solvent at about 65 °C on a hot plate under continuous stirring. After 80 min, the solution was poured into a Petri dish and placed in an oven for drying at about 50 °C. A mixed solution of alcohol and water (1:1 v/v) was prepared, and a phthalic acid cross-linker (1 g) was dissolved with a certain amount of SDS. The cross-linker solution was poured on the surface of the PSF membrane and left to sit for 5 min. After a specific time, the surplus solution was exhausted, and the membrane was dehydrated in the oven at 30 °C for 20 min (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gradient cross-linked PVP membrane synthesis process.

An aqueous PVP solution was prepared by dissolving PVP (1 g) in deionized water (25 mL) at about 70 °C for 60 min. After that, the solution was cooled to room temperature. The concentrated sulfuric acid (1 mL) was added to the PVP solution, which acted as a catalyst. The phthalic acid cross-linked saturated PSF membrane was sodden in a PVP solution for about 5 min and excess solution. Then, the PVP membrane was dried at 80 °C for 15 min (Figure 2).

2.5. Characterization of Membranes

2.5.1. Contact Angle (CA) Measurement

The hydrophilicity of the sample was analyzed based on contact angle determination, and a CA goniometer (Digidrop, KSV Instruments) instrument, along with the video captured, was used. The sample was dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 48 h. Three to five readings were obtained for each sample, and deionized water was poured by a microsyringe on the sample surface. All angles were measured immediately as the drops were released to avoid errors due to evaporation.

2.5.2. Volatile Matter

A hexane–acetone (1:1 v/v) mixture was used for the PAH examination to extract 5 g of each sample by ultrasound using the SPE cartridges (strata SI-I Silica, Phenomenex, Torrance). The extracted samples were purified, and the investigation was accomplished by a gas chromatography/discerning mass detector (6890 N/5975, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara) approved by the US EPA. Using electron ionization (70 EV), the GC/MS was conducted in a throbbed splitless regime (1 μL injection at 300 °C, 25 lb per square inch pulse pressure, 70 mL/min purge flow for 0.75 min) at a temperature of 50 °C for 1 min, then elevated at 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min and kept for 10 min. A PAH analysis curve (SV calibration Mix 5, Restek, Bellefonte) ranged from 10 to 1000 μg/L and was linear (all R2 > 0.9981). The PAH analyzed sample analysis extent was 1.7–5.8 μg/kg dw with (p-terphenyl-d14, Restek, Bellefonte) alternate storing ranging 88–117%. During composting and vermicomposting, the PAH values were rectified by considering the weight loss of the organic waste mixture, as reported in eq 1.

| 1 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Contact Angle and Flux Study

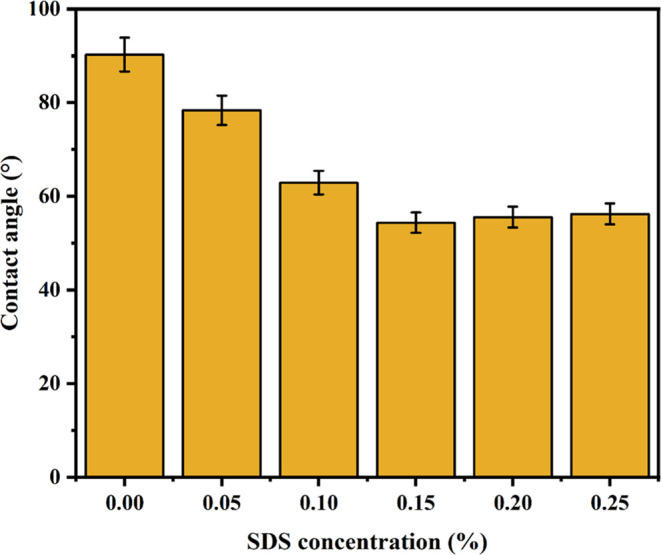

The contact angle of a membrane refers to the angle formed between the liquid interface and the solid surface of the membrane.35,36 It is a measure of the wettability of the membrane, indicating how well a liquid spreads or adheres to the membrane surface.37,38 A hydrophilic membrane has a contact angle of less than 90°, typically from 0 to 90°. Hydrophilic membranes have a strong affinity for water and polar solvents. A hydrophobic membrane has a contact angle greater than 90°, typically from 90 to 180°.39 Hydrophobic membranes repel water or polar solvents and are more compatible with nonpolar liquids.40 It is important to note that various factors, including surface chemistry, roughness, temperature, and the nature of the fluid in contact with the membrane, can influence the contact angle of a membrane.41,42

The contact angle of a membrane has an effect on membrane fouling. The contact angle affects the wettability of the membrane surface, and wettability plays a significant role in membrane fouling.37 Hydrophilic membranes generally exhibit less fouling because the liquid can easily wet the surface, minimizing the chance of foulants depositing or adhering to the membrane.43 Hydrophobic membranes are more prone to fouling because foulants, such as organic compounds or particles, can easily attach to the membrane surface due to the limited interaction between the liquid and the membrane.35,41

The addition of SDS to a membrane influences its contact angle. The specific effect of SDS on the contact angle depends on the concentration of SDS, the surface chemistry of the membrane, and the surrounding environment. SDS is known to possess hydrophilic properties due to oxygen-containing functional groups on its surface, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups. When added to a membrane, SDS increases the hydrophilicity of the membrane surface. As a result, the contact angle of the membrane decreases, indicating improved wettability and increased affinity for water or polar solvents. The functional groups on SDS interact with the surface of the membrane, leading to changes in the surface chemistry. This interaction modifies the contact angle depending on the specific interactions involved.

The water contact angle value for the PVP membrane was 90.2° (Figure 3). With more SDS injected, it was seen that the contact angle values decreased. This indicates that the addition of SDS produced more hydrophilic membranes. This was due to the introduction of polar functional groups, such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, and epoxy, to the surface and sheet edges during the oxidation of graphite. Adding hydrophilicity to membranes minimizes the advantageous surface-foulant interactions and hence minimizes membrane fouling.

Figure 3.

Water contact angle for various concentrations of SDS added to the PVP membrane.

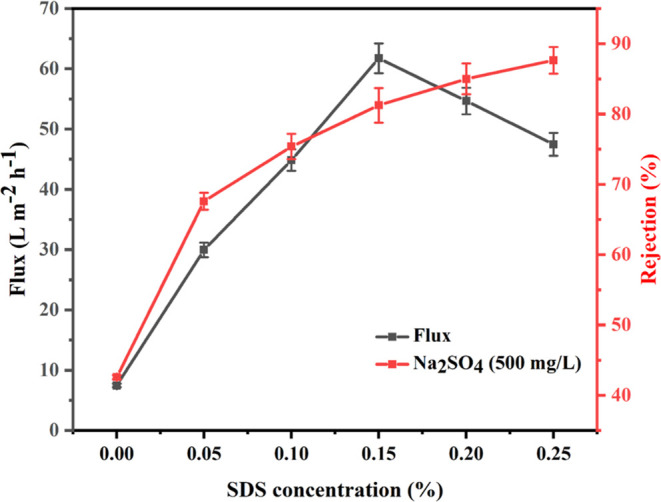

The PVP membrane exhibits a low membrane flux of 7.5 ± 0.3 L m–2 h–1, as shown in Figure 4. The low membrane flux is due to a high water contact angle and hydrophobicity. The addition of SDS to a membrane has a positive effect on the membrane flux. The addition of SDS to a membrane improves the membrane flux. SDS has a two-dimensional structure with a high aspect ratio and excellent mechanical properties. When incorporated into a membrane, they create nanochannels or nanopores, thereby facilitating the transport of fluids through the membrane. The presence of SDS reduces the effective thickness of the membrane, increases the effective pore size, and promotes better flow characteristics, resulting in enhanced permeability and higher flux rates. The addition of SDS results in higher membrane flux because of the improvement of membrane pore size and reduction of the water contact angle. The highest membrane flux of 61.7 ± 2.5 L m–2 h–1 was observed for 0.15% SDS-PVP membrane, while the flux values decreased for higher SDS concentrations. The reduction in membrane flux is due to poor dispersion of SDS in the dope solution.

Figure 4.

Membrane flux and salt rejection for various SDS concentrations.

The concentration of SDS in the membrane matrix is a critical parameter affecting the membrane flux. Studies have shown that an optimal SDS concentration exists beyond which the flux improvement diminishes or even declines. At higher concentrations, SDS agglomerates and blocks the membrane pores, impeding fluid flow and reducing membrane flux. Therefore, it is important to carefully control the SDS concentration and ensure uniform dispersion within the membrane matrix to achieve the desired flux enhancement.

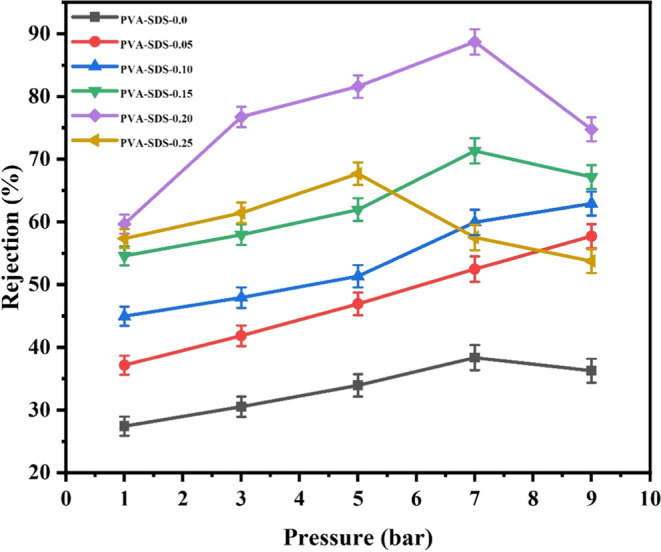

3.2. Effect of Pressure on Salt Rejection

The addition of SDS to the membrane influences the salt rejection capabilities, which are critical for desalination and other separation processes.44,45 The concentration of SDS incorporated into the membrane matrix plays a crucial role in determining the resulting salt rejection properties. While an optimal SDS concentration enhances salt rejection, higher concentrations increase membrane fouling or pore blockage, negatively impacting salt rejection efficiency.41,45 It is important to carefully control the SDS concentration and ensure a uniform dispersion within the membrane matrix to achieve the desired salt rejection performance. The dense polymer matrix of the PVP membrane restricts the passage of salt ions while allowing the permeation of water molecules.46 As a result, the PVP membrane typically demonstrates high salt rejection capabilities. However, adding SDS decreases salt rejection, and higher SDS concentrations result in lower salt rejection. This indicates that even though treatment with SDS led to more hydrophilic membranes, their performance in terms of salt rejection was inferior to that of the unmodified membranes. This may be due to the expanded pores, where SDS caused the pores to grow.

Figure 5 shows the effect of the pressure on salt rejection for different membrane types. The results showed that lower salt rejection was observed at higher pressure. Increasing the applied pressure has negative effects on membrane flux. Higher pressure increases concentration polarization, which is the accumulation of solutes near the membrane surface.47 Concentration polarization hinders mass transfer and decreases the effective driving force for permeation. Increasing the pressure reduces the convective flow, increasing the concentration polarization layer and reducing the membrane flux.48

Figure 5.

Effect of pressure and various SDS concentrations in salt (Na2SO4 salt (500 mg/L))rejection.

Excessive pressure led to pore blockage or membrane fouling in PVP membranes. As the pressure increases, particles or fouling agents will likely be forced into the membrane pores.49 This results in a reduced effective pore size, increased resistance to flow, and subsequent decline in membrane flux over time. It is important to note that the effect of pressure on the membrane flux in PVP membranes should be optimized within a suitable range. Operating at excessively high pressures leads to diminishing returns and even membrane damage. Balancing the membrane’s pressure, selectivity, and long-term stability is crucial for achieving optimal membrane flux.

The addition of SDS to membranes has a significant impact on the salt rejection properties. SDS-modified membranes exhibit enhanced salt rejection due to size exclusion effects, electrostatic interactions, and selectivity. However, the concentration and dispersion of SDS, membrane structure, and solution conditions are critical in determining the final salt rejection performance. Further research and optimization efforts are needed to fully exploit the potential of SDS-modified membranes for efficient salt rejection in various separation processes.

3.3. Rejection Studies with Specific PAHs

PVP membranes have gained attention for various water treatment applications including removal of organic contaminants such as PAHs. PAHs are diverse organic compounds with two or more fused benzene rings. They are ubiquitous in the environment due to natural processes (e.g., forest fires and volcanic eruptions) and anthropogenic activities (e.g., combustion of fossil fuels and industrial discharges). The results of rejection studies with specific PAHs have helped us to improve our understanding of the toxicity of these compounds. This information can be used to develop strategies to reduce exposure to PAHs and prevent their harmful effects.

Pyrene is a PAH consisting of four fused benzene rings. It is a colorless solid with slight blue fluorescence. Pyrene is a known carcinogen and can cause other health problems such as liver damage. Pyrene has a higher-molecular-weight PAH, and removal studies have indicated that PVP membranes exhibit substantial rejection capabilities for this compound.50 The rejection rate of pyrene exceeded 85% using PVP membranes, as shown in Figure 6. The presence of SDS in the membrane structure enhanced the molecular sieving effect, restricting the passage of pyrene molecules through the membrane.51 PVP membranes have shown significant rejection of acephthene. An acephthene rejection rate of 85% was observed with a 0.2% SDS-PVP membrane. While comparing the performance of cross-linking PVP and pristine PVP membranes, the cross-linking PVP membrane exhibited higher rejection of acephthene, with rejection rates above 85%. The high rejection was attributed to the enhanced adsorption and size exclusion properties of the SDS in the membrane matrix. The cross-linking PVP successfully demonstrated a high rejection rate of 85% for naphthalene. The cross-linked PVP matrix acted as a barrier, effectively preventing the passage of naphthalene molecules through the membrane.

Figure 6.

Effect of SDS concentration on PAHs removal.

Cross-linking PVP membranes have emerged as a promising approach to efficiently remove specific PAHs from contaminated water sources. These membranes exhibit impressive capabilities, owing to the distinctive properties of the cross-linking agents employed. Notably, these agents possess a large surface area, high adsorption capacity, and a molecular sieving effect, all of which contribute to the heightened rejection efficiency of the membrane. The surface area increases the interaction between the PAH molecules and the membrane, promoting effective adsorption. The high adsorption capacity ensures that the membrane can capture a significant quantity of PAHs, while the molecular sieving effect sieves out PAHs based on their molecular size and configuration.

However, it is essential to recognize that the efficiency of PAH rejection in cross-linking PVP membranes is subject to several influencing factors. First, the concentration of surfactants like SDS in the solution can impact the membrane’s performance, as it alters the interaction between the PAHs and the membrane surface. Additionally, the method used for membrane preparation, including factors like cross-linking agent concentration and duration, can affect the membrane’s structure and, consequently, its rejection efficiency. Furthermore, operating conditions, such as pressure and temperature, play a role in determining how effectively PAHs are rejected. Lastly, the specific PAH compound being targeted also matters, as different PAHs’ molecular structure and size can lead to variations in their rejection rates. Hence, when designing and utilizing cross-linking PVP membranes for PAH removal, carefully considering these factors is paramount to achieving optimal results and efficiently mitigating PAH contamination in water sources.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, developing a gradient cross-linking PVP membrane has shown promise for the efficient removal of PAHs from water sources. Cross-linking the PVP membrane has demonstrated a notable effect on the contact angle of the membrane surface. Integrating SDS into the PVP matrix increased hydrophilicity, resulting in a lower contact angle. Cross-linking PVP membranes have exhibited improved membrane flux compared to traditional membranes. This enhanced wettability allows for better wetting and improved interactions with water or aqueous solutions, which are advantageous for various separation processes. The cross-linking PVP membrane offers surface hydrophilicity, membrane flux, and salt rejection advantages. The performance evaluation of the gradient cross-linking PVP membrane has demonstrated enhanced rejection efficiency for various PAH compounds, including naphthalene, phenanthrene, and pyrene. The innovative membrane design, combining the benefits of gradient cross-linking, addresses conventional NF membranes’ rejection efficiency and fouling resistance limitations. The gradient cross-linking PVP membrane holds great promise as an advanced membrane technology for the efficient and sustainable removal of PAHs from water sources, contributing to improved water quality and environmental protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Deputy for Research and Innovation—Ministry of Education, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for this research through a grant (NU/IFC/2/SERC/-/2) under the Institutional Funding Committee at Najran University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Kim K.-H.; Jahan S. A.; Kabir E.; Brown R. J. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects. Environ. Int. 2013, 60, 71–80. 10.1016/j.envint.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitha T.; Satyaprakash M.; Vani S. S.; Sadhana B.; Padal S. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: their transport, fate and biodegradation in the environment. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6 (4), 1627–1639. 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.604.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Zhang L.; Cao Y.; Colella N. S.; Liang Y.; Bredas J.-L.; Houk K. N.; Briseno A. L. Unconventional, chemically stable, and soluble two-dimensional angular polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: from molecular design to device applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (3), 500–509. 10.1021/ar500278w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Shafy H. I.; Mansour M. S. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25 (1), 107–123. 10.1016/j.ejpe.2015.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Idowu O.; Semple K. T.; Ramadass K.; O’Connor W.; Hansbro P.; Thavamani P. Beyond the obvious: Environmental health implications of polar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 543–557. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turki N.; Boujelben N.; Bakari Z.; Kettab A.; Bouzid J. Removal of organic and nitrogen compounds from landfill leachates by coagulation, Fenton, and adsorption coupling processes. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 213, 279–287. 10.5004/dwt.2021.26697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C.; Han Y.; Duan Y.; Lai X.; Fu R.; Liu S.; Leong K. H.; Tu Y.; Zhou L. Review on the contamination and remediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coastal soil and sediments. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112423 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M. A.; Scelza R.; Scotti R.; Gianfreda L. Role of enzymes in the remediation of polluted environments. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010, 10 (3), 333–353. 10.4067/S0718-95162010000100008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haripriyan U.; Gopinath K.; Arun J.; Govarthanan M. Bioremediation of organic pollutants: A mini review on current and critical strategies for wastewater treatment. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204 (5), 286 10.1007/s00203-022-02907-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Luqueño F.; Valenzuela-Encinas C.; Marsch R.; Martínez-Suárez C.; Vázquez-Núñez E.; Dendooven L. Microbial communities to mitigate contamination of PAHs in soil--possibilities and challenges: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2011, 18 (1), 12–30. 10.1007/s11356-010-0371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstandt K.; Peinemann K.-V.; Skilhagen S. E.; Thorsen T.; Holt T. Membrane processes in energy supply for an osmotic power plant. Desalination 2008, 224 (1–3), 64–70. 10.1016/j.desal.2007.02.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadri T.; Rouissi T.; Kaur Brar S.; Cledon M.; Sarma S.; Verma M. Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by fungal enzymes: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 51, 52–74. 10.1016/j.jes.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldos H. I.; Zouari N.; Saeed S.; Al-Ghouti M. A. Recent advances in the treatment of PAHs in the environment: Application of nanomaterial-based technologies. Arabian J. Chem. 2022, 15 (7), 103918 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Wang Z.; Chen H.; Cai T.; Liu Z. Hydrochar and pyrochar for sorption of pollutants in wastewater and exhaust gas: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115910 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Luo J.; Huang Z.; Liu L.; Wang H.; Ruan G.; Zhao C.; Du F. Recent advances in separation applications of polymerized high internal phase emulsions. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44 (1), 169–187. 10.1002/jssc.202000612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie-Martin C. L.; Stratton K. G.; Teeguarden J. G.; Waters K. M.; Simonich S. L. M. Implications of Bioremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Soils for Human Health and Cancer Risk. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (17), 9458–9468. 10.1021/acs.est.7b02956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mai B. X.; Fu J. M.; Sheng G. Y.; Kang Y. H.; Lin Z.; Zhang G.; Min Y. S.; Zeng E. Y. Chlorinated and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in riverine and estuarine sediments from Pearl River Delta, China. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 117 (3), 457–474. 10.1016/S0269-7491(01)00193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J.; Huang G.; An C.; Yu H. Investigation on the solubilization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the presence of single and mixed Gemini surfactants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 190 (1), 840–847. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Guo C.; Hao J.; Zhao Z.; Long H.; Li M. Adsorption of heavy metal ions by sodium alginate based adsorbent-a review and new perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4423–4434. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M.; Tong S.; Zhao S.; Jia C. Q. Adsorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from water using petroleum coke-derived porous carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181 (1–3), 1115–1120. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves S. R.; Calori I. R.; Tedesco A. C. Photosensitizer-based metal-organic frameworks for highly effective photodynamic therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2021, 131, 112514 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.; Sang W.; Jiang R.; Gao Y. Cation-exchange fluoropolymer membranes with the conjugate acid of 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroaniline as an alternative proton-exchange group. J. Fluorine Chem. 2019, 218, 76–83. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2018.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Di M.; Liu J.; Gao L.; Yan X.; He G. Continuous Covalent Organic Frameworks Membranes: From Preparation Strategies to Applications. Small 2023, 19, 2303757 10.1002/smll.202303757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Bilad M. R.; Man Z.; Wibisono Y.; Jaafar J.; Mahlia T. M. I.; Khan A. L.; Aslam M. Recent progress in integrated fixed-film activated sludge process for wastewater treatment: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 268, 110718 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Harun N. Y.; Bilad M. R.; Samsuri T.; Nordin N. A. H. M.; Shamsuddin N.; Nandiyanto A. B. D.; Huda N.; Roslan J. Response surface methodology for optimization of rotating biological contactor combined with external membrane filtration for wastewater treatment. Membranes 2022, 12 (3), 271. 10.3390/membranes12030271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N.; Murthy Z. V. P. Synthesis and application of ZIF-67 on the performance of polysulfone blend membranes. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 23, 100685 10.1016/j.mtchem.2021.100685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaydhane M. K.; Sharma C. S.; Majumdar S. Electrospun nanofibres in drug delivery: advances in controlled release strategies. RSC Adv. 2023, 13 (11), 7312–7328. 10.1039/D2RA06023J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banitaba S. N.; Ebadi S. V.; Salimi P.; Bagheri A.; Gupta A.; Arifeen W. U.; Chaudhary V.; Mishra Y. K.; Kaushik A.; Mostafavi E. Biopolymer-based electrospun fibers in electrochemical devices: versatile platform for energy, environment, and health monitoring. Mater. Horiz. 2022, 9 (12), 2914–2948. 10.1039/D2MH00879C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Bilad M. R.; Man Z. B.; Suleman H.; Nordin N. A. H.; Jaafar J.; Othman M. H. D.; Elma M. An energy-efficient membrane rotating biological contactor for wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124544 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y.; Horiuchi H.; Fukasawa S.; Takesawa S.; Hirayama J. Influences of the priming procedure and saline circulation conditions on polyvinylpyrrolidone in vitro elution from polysulfone membrane dialyzers. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 28, 101140 10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.101140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Bilad M. R.; Man Z. B.; Klaysom C.; Jaafar J.; Khan A. L. An integrated rotating biological contactor and membrane separation process for domestic wastewater treatment. Alexandria Eng. J. 2020, 59 (6), 4257–4265. 10.1016/j.aej.2020.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Harun N. Y.; Arshad U.; Laziz A. M.; Mun S. L. S.; Bilad M. R.; Nordin N. A. H.; Alsaadi A. S. Optimization of operational parameters using RSM, ANN, and SVM in membrane integrated with rotating biological contactor. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140830 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Li K.; Shi W.; Cai J. Chitosan/polyvinylpyrrolidone/polyvinyl alcohol/carbon nanotubes dual layers nanofibrous membrane constructed by electrospinning-electrospray for water purification. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 294, 119756 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Harun N. Y.; Sambudi N. S.; Arshad U.; Nordin N. A. H. M.; Bilad M. R.; Saeed A. A. H.; Malik A. A. SVM and ANN Modelling Approach for the Optimization of Membrane Permeability of a Membrane Rotating Biological Contactor for Wastewater Treatment. Membranes 2022, 12 (9), 821. 10.3390/membranes12090821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruwoldt J.; Blindheim F. H.; Chinga-Carrasco G. Functional surfaces, films, and coatings with lignin–a critical review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13 (18), 12529–12553. 10.1039/D2RA08179B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H.; Sun F.; Zhang J.; Wang Y.; Yang S.; Xing D. Gradient crosslinking optimization for the selective layer to prepare polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) nanofiltration (NF) membrane: The enhanced filtration performance and potential rejection for EDCs. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 675, 121548 10.1016/j.memsci.2023.121548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Wang J.; Zhou S.; Xue A.; Wu F.; Zhao Y. Polyacrylonitrile-supported self-aggregation crosslinked poly (vinyl alcohol) pervaporation membranes for ethanol dehydration. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 122, 109359 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.109359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X.; Wang Z.; Quan S.; Xu Y.; Jiang Z.; Shao L. Exploring the synergetic effects of graphene oxide (GO) and polyvinylpyrrodione (PVP) on poly (vinylylidenefluoride)(PVDF) ultrafiltration membrane performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 316, 537–548. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.07.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Harun N. Y.; Sambudi N. S.; Bilad M. R.; Abioye K. J.; Ali A.; Abdulrahman A. A Review of Rotating Biological Contactors for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2023, 15 (10), 1913. 10.3390/w15101913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beygmohammdi F.; Kazerouni H. N.; Jafarzadeh Y.; Hazrati H.; Yegani R. Preparation and characterization of PVDF/PVP-GO membranes to be used in MBR system. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 154, 232–240. 10.1016/j.cherd.2019.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeshan M. H.; Khan R. U.; Shafiq M.; Sabir A. Polyamide intercalated nanofiltration membrane modified with biofunctionalized core shell composite for efficient removal of Arsenic and Selenium from wastewater. J. Water Process. Eng. 2020, 34, 101175 10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Harun N. Y.; Sambudi N. S.; Abioye K. J.; Zeeshan M. H.; Ali A.; Abdulrahman A.; Alkhattabi L.; Alsaadi A. S. Effect of operating parameters on the performance of integrated fixed-film activated sludge for wastewater treatment. Membranes 2023, 13 (8), 704. 10.3390/membranes13080704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M.; Waqas S.; Khan J. A.; Rahman S.; Kruszelnicka I.; Ginter-Kramarczyk D.; Legutko S.; Ochowiak M.; Włodarczak S.; Czernek K. Effect of Operating Parameters and Energy Expenditure on the Biological Performance of Rotating Biological Contactor for Wastewater Treatment. Energies 2022, 15 (10), 3523. 10.3390/en15103523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su Q.-W.; Lu H.; Zhang J.-Y.; Zhang L.-Z. Fabrication and analysis of a highly hydrophobic and permeable block GO-PVP/PVDF membrane for membrane humidification-dehumidification desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 582, 367–380. 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozekmekci M.; Unlu D.; Copur M. Removal of boron from industrial wastewater using PVP/PVDF blend membrane and GO/PVP/PVDF hybrid membrane by pervaporation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 1859–1869. 10.1007/s11814-021-0845-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas S.; Bilad M. R.; Aqsha A.; Harun N. Y.; Ayoub M.; Wirzal M. D. H.; Jaafar J.; Mulyati S.; Elma M. Effect of membrane properties in a membrane rotating biological contactor for wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9 (1), 104869 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Liu Y.; Guo Y.; Wang C.; Hu Z.; Zhang C. High-hydrophilic and salt rejecting PA-g/co-PVP RO membrane via bionic sand-fixing grass for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 357, 269–279. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu A.; Liu Y.; Zheng J.; Wang X.; Xia S.; Van der Bruggen B. Tailoring properties and performance of thin-film composite membranes by salt additives for water treatment: A critical review. Water Res. 2023, 234, 119821 10.1016/j.watres.2023.119821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Field R. W.; Wu J. J.; Zhang K. Polyvinylpyrrolidone modified graphene oxide as a modifier for thin film composite forward osmosis membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 540, 251–260. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.06.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu I.; Topacik D. Effects of operating conditions on the salt rejection of nanofiltration membranes in reactive dye/salt mixtures. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2003, 33 (3), 283–294. 10.1016/S1383-5866(03)00088-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.-R.; Wang J.-N.; Li C.-J. Strategies for improving the performance of the polyamide thin film composite (PA-TFC) reverse osmosis (RO) membranes: Surface modifications and nanoparticles incorporations. Desalination 2013, 328, 83–100. 10.1016/j.desal.2013.08.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Kaur S.Thin Film Nanofibrous Composite Electrospun Membrane for Separation of Salts, 2011.

- Malatjie K. I.Polyamide Thin Film Composite Membranes Modified with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Acrylic Acid for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater; University of Johannesburg: South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bell E. A.; Poynor T. E.; Newhart K. B.; Regnery J.; Coday B. D.; Cath T. Y. Produced water treatment using forward osmosis membranes: Evaluation of extended-time performance and fouling. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 525, 77–88. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kibechu R. W.; Ndinteh D. T.; Msagati T. A. M.; Mamba B. B.; Sampath S. Effect of incorporating graphene oxide and surface imprinting on polysulfone membranes on flux, hydrophilicity and rejection of salt and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from water. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C 2017, 100, 126–134. 10.1016/j.pce.2017.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]