Abstract

The interplay between cells and their microenvironments plays a pivotal role in in vitro drug screening. Creating an environment that faithfully mimics the conditions of tumor cells within organ tissues is essential for enhancing the relevance of drug screening to real-world clinical scenarios. In our research, we utilized chemical decellularization techniques to engineer liver-decellularized extracellular matrix (L-dECM) scaffolds. These scaffolds were subsequently recellularized with HepG2 cells to establish a tumor organoid-like tissue model. Compared to the conventional tissue culture plate (TCP) culture, the tumor organoid-like tissue model demonstrated a remarkable enhancement in HepG2 cell growth, leading to increased levels of albumin secretion and urea synthesis. Additionally, our results revealed that, within a 3-day time frame, the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin (DOX) against cells cultured in the tumor organoid-like tissue model was notably reduced when compared to cells grown on TCPs. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the cytotoxicity of two compounds, triptolide and honokiol, both derived from traditional Chinese medicine, between TCP culture and the tumor organoid-like tissue culture, indicating a lack of substantial drug resistance. Western blotting assays further confirmed our findings by revealing elevated expressions of E-cadherin and vimentin proteins, which are closely associated with the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). These results underscored that the tumor organoid-like tissue model effectively promoted the EMT process in HepG2 cells. Moreover, we identified that triptolide and honokiol possess the capacity to reverse the EMT process in HepG2 cells, whereas DOX did not exhibit a significant effect. In light of these findings, the tumor organoid-like tissue model stands as a valuable predictive platform for screening antitumor agents and investigating the dynamics of the EMT process in tumor cells.

Introduction

Cancer has emerged as one of the most formidable diseases and currently poses a significant threat to humanity. Primary modalities for cancer treatment include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy. At present, chemotherapy remains a cornerstone in the management of tumors. Despite the advancements in cutting-edge technologies, such as nanomedicine and antibody-based immunotherapy, there persist numerous challenges in cancer treatment.1−3 Consequently, researchers continue to endeavor in the development of novel chemotherapy agents, including those derived from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Nevertheless, many drug candidates have encountered issues related to safety and efficacy during phase II and III clinical trials.4In vitro cell assays and preclinical animal studies assume paramount importance in assessing the antitumor activity of drugs before meticulous evaluation in clinical trials. Evaluating drug efficacy in vitro not only serves to reduce costs in the initial stages of drug development and increase the success rate of cancer drug screening in clinical trials but also aids in identifying the most efficacious treatment for cancer patients.

Traditionally, the two-dimensional (2D) culture method involving the direct inoculation of tumor cells onto tissue culture plates (TCPs) is a widely adopted approach. However, owing to the robust physical contact between cells and 2D substrates, the heightened integrin signaling observed in 2D cultures, and the inability to faithfully replicate cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions seen in vivo, this method fails to accurately mirror the drug response observed in clinical patients.5 As a result, there has been a recent surge in the development of three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models for drug screening. For instance, Li et al. created 3D HepG2 cell spheroids using microfiber rods as substrates, offering a high-throughput screening model that predicts drug metabolism and tumor infiltration.6 He et al. designed a 3D tumor model chip with a “layer cake” structure to screen epirubicin and paclitaxel with MDA-MB-231 cells, demonstrating notable advantages in terms of customization, accuracy, replication of the microenvironment, and tumor functionalization.7 Additionally, the fabrication of large porous microspheres using microfluidic technology has proven to be an excellent platform for 3D cell culture in drug screening.8

In recent years, organoid technology has made significant advancements, enabling the emulation of intricate spatial structures and functional characteristics of native organs. The development of tumor organoids is instrumental in the characterization of various biological behaviors within tumors, encompassing proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance.9 Nonetheless, the construction of tumor organoids continues to face numerous challenges. Patient-derived organoid materials are primarily sourced from surgical specimens or biopsies, and factors such as sample quantity, size, and the presence of tumor epithelial cells within biopsy tissues can substantially impact the success rate of organoid culture.9 Moreover, the current procedure for establishing organoids for drug sensitivity screening and optimizing clinical decisions is time-intensive. This implies that its application in rapidly progressing late-stage or metastatic malignancies may potentially cause treatment delays due to the deteriorating condition of the patients.10 The choice of the culture matrix for organoid cultivation is equally critical. While the collagen matrix is cost-effective, it may not offer a broader range of extracellular matrix components and cytokines. Its hydrogel structure is susceptible to alterations, limiting its ability to faithfully replicate cellular–matrix interactions.11 On the other hand, the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm matrix, extracted from mouse tumors, although compositionally rich, fails to accurately replicate the structural properties of native tissues, and its high cost restricts its widespread application.12

Decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds are biomaterials created through the application of decellularization technology to human or animal tissues, effectively eliminating immunogenic cellular components.13 These dECM scaffolds faithfully mimic the microenvironment of native tissues, offering unique opportunities for generating tissues with specific structures.14 Notably, unlike synthetic materials, the ECM is rich in proteoglycans, collagens, laminins, glycosaminoglycans, and other bioactive components that play pivotal roles in regulating cellular functions, such as proliferation, differentiation, migration, cell survival, and drug resistance.15,16 Consequently, ECM scaffold-based biomaterials have found widespread applications in tissue repair and regeneration, encompassing areas like bone, the central nervous system, and the cardiovascular system.17−19 The combination of dECM with natural or synthetic polymers, along with the addition of bioactive factors, has been employed to develop composite platforms for simulating tissue microenvironments. This approach finds extensive applications in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.20 Saleh et al. enhanced the activity of the decellularized hepatic scaffold by coupling the homogenized liver extracellular matrix onto it.21 This modification resulted in superior cell proliferation, improved cell diffusion, and enhanced vascular generation capabilities. Moreover, the ECM is a critical constituent of the tumor microenvironment, exerting a profound influence on tumorigenesis, drug resistance, and metastasis.22 Mano et al. have engineered a breast cancer cell model enriched with dECM fragments derived from breast tissue, successfully recapitulating the invasive characteristics of metastatic breast cancer cells and mirroring the metabolic properties of human tumors. This innovative model serves as a valuable platform for drug candidate screening.23

The liver, as the foremost metabolic organ in the human body, plays a pivotal role in various physiological processes. Unfortunately, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a prevalent malignant disease responsible for millions of annual global fatalities. While systemic therapy represents a treatment modality for HCC, the number of approved chemotherapeutics for advanced cases remains limited, with sorafenib and lenvatinib being notable exceptions.24 HCC is renowned for its resistance to chemotherapy, a characteristic often associated with the upregulation of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase and multidrug resistance proteins.25 Doxorubicin (DOX), an antimicrobial antibiotic with a broad spectrum of antineoplastic properties, had been under evaluation for HCC treatment before approval of sorafenib. However, the phase III clinical trial failed to demonstrate significant survival benefits.25 TCM has a rich history in cancer treatment, and the role of TCM in HCC therapy has gained substantial attention, with clinical trials investigating the effectiveness of several approved TCM formulations.26 Hence, the establishment of convenient and efficient in vitro liver cancer tumor organoid-like tissue models holds promise for advancing drug screening methods in the context of HCC.

In this study, we established a tumor organoid-like tissue model using the liver-derived decellularized extracellular matrix (L-dECM) as a scaffold to assess the effects of doxorubicin (DOX) and two monomeric compounds from TCM, namely, triptolide and honokiol, on liver cancer (see Figure 1). The L-dECM scaffold was prepared through decellularization techniques and then used for recellularization with HepG2 cells. Subsequently, we examined the cytotoxicity of DOX, triptolide, and honokiol and investigated their impact on the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) process in HepG2 cells, along with the influence of the extracellular matrix on drug toxicity. This tumor organoid-like tissue model offers the potential to provide a more convenient, effective, and physiologically relevant in vitro screening approach for the evaluation of novel drugs in the context of liver cancer. Furthermore, it provides valuable insights into the selection of matrix materials for the development of organoid models.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of constructing the tumor organoid-like tissue and a drug screening strategy.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Triton X-100, paraformaldehyde, and magnesium chloride were procured from Aladdin Industrial (Beijing, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), DNase, Cell Counting Kit-8 assay kit, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), and trypsin were acquired from Life Technologies of Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham). The total protein assay kit, albumin quantification kit, and urea nitrogen kit were obtained from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). DOX, triptolide, and honokiol were obtained from Macklin Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Other chemical reagents were received from Kelong Reagent Company Co. (Chengdu, China).

Preparation of the Liver-Decellularized Extracellular Matrix

Fresh porcine livers were sourced from a local abattoir and subsequently processed for decellularization. The livers were initially sectioned into slices measuring 1 cm in length, 1 cm in width, and 0.3 cm in thickness (L × W × thickness), followed by a thorough wash in sterile PBS supplemented with antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin). To generate liver-decellularized extracellular matrix (L-dECM) scaffolds, a detergent-based treatment protocol was employed. Specifically, the liver slices were immersed in a solution of Triton X-100 (1.0% v/v) and subjected to agitation for a period of 2 days at room temperature, with a change of solution every 12 h. Subsequently, the remaining slices underwent incubation in a solution containing DNase (300 U/mL) and magnesium chloride (50 mmol/L) at 37 °C for a duration of 3 h. After thorough rinsing with PBS, the L-dECM scaffolds were freeze-dried and stored at −70 °C for subsequent utilization.

Characterization of Liver-Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Based Scaffolds

The freeze-dried sections of native liver tissue and L-dECM were affixed to conductive tape and subsequently coated with a thin gold layer (approximately 2 nm thick). The morphological characteristics of both the native liver tissue sections and the L-dECM scaffold were observed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Phenom ProX, Netherlands).

Following fixation with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, the native liver tissue and L-dECM scaffold underwent a series of processing steps that included dehydration and subsequent paraffin embedding, ultimately enabling the generation of 5 μm thick sections. These sections were subjected to staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, Beyotime, China), facilitating the microscopic observation of cellular components and residual DNA by a microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ts2, Japan). Furthermore, the sections were subjected to Masson’s Trichrome staining (Beyotime, China) to visually demonstrate the presence of collagen.

The quantification of DNA content within both the native liver tissue and L-dECM scaffold was performed with the utilization of the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In a concise summary, the freeze-dried sections of native liver tissue and the L-dECM scaffold were subjected to incubation in a lysis buffer at 55 °C for a duration of 12 h. Subsequently, DNA purification was achieved through phenol/chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The residual DNA content was assessed employing a DNA protein analyzer (Quawell Q6000). Furthermore, the protein content of both the L-dECM scaffold and native liver tissue was determined using a BCA Protein Assay kit (Beyotime, China).

Preparation of the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Organoid-like Model

The HepG2 cell line, procured from the Beijing Stem Cell Bank in Beijing, China, was cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS under standard conditions at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. To prepare the L-dECM scaffolds for cell culture, they were first immersed in 75% ethanol for 10 min, followed by thorough washing with sterile PBS. Subsequently, the L-dECM scaffolds were incubated overnight in DMEM cell culture medium. For the generation of a tumor organoid-like model, the L-dECM scaffolds were sectioned into comparable dimensions and seeded onto the bottom of 48-well plates. The harvested HepG2 cells were adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL and cocultured with the scaffolds to form tumor organoid-like tissues. In parallel, HepG2 cells grown on TCP were maintained as a control group. The cells were cultured at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, with medium replacement occurring every other day.

Cell Proliferation Analysis

Following a 2-day incubation period, the tumor organoid-like tissues and glass slides were meticulously fixed with a precooled paraformaldehyde solution. Subsequently, they underwent a stepwise gradient dehydration process with ethanol, and the cell morphology was scrutinized through SEM. Concurrently, another set of experiments was conducted. The tumor organoid-like tissue was initially fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning for subsequent H&E staining. In addition, cell activity was monitored on a daily basis throughout a 7-day cell culture period via the utilization of the CCK-8 assay kit. Simultaneously, albumin secretion in the culture media was quantified employing an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method with the use of an albumin quantification kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Furthermore, the expression levels of urea were evaluated using a urea nitrogen kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) as the specific reaction with diacetyl monoxime. Absorbance values were determined using a microplate reader (Elx-800, Bio-Tek Instrument Inc., Winooski, VT). Both albumin and urea quantities in the culture media were normalized based on cell numbers.

Drug Treatment and Cytotoxicity Assay

Following the preparation of tumor organoid-like tissue, different concentrations of DOX, triptolide, and honokiol were introduced into the culture medium. Specifically, the series concentrations of DOX and triptolide were established at 0.04, 0.2, 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 μg/mL, while the concentrations of honokiol were configured at 0.2, 1, 10, 25, and 50 μg/mL. Subsequent to a 72 h incubation period, cytotoxicity assessments were conducted using the CCK-8 assay kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, after the incubation with the drugs, the organoid-like tissues were rinsed with PBS, followed by the addition of 200 μL of fresh medium and subsequently 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent. This mixture was allowed to incubate for an additional 4 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed after plate agitation, and the absorbance at 450 nm was quantified by using a microplate reader (Elx-800, Bio-Tek Instrument Inc., Winooski, VT). Furthermore, in a separate set of experiments, an albumin quantification kit and a urea nitrogen kit were employed to assess the content of albumin and urea in the medium at 2, 4, and 6 days, following the addition of DOX (concentration of 1.0 μg/mL), triptolide (1.0 μg/mL), and honokiol (10.0 μg/mL), respectively.

Western Blot Assay

Following a 1-day incubation period, DOX (concentration: 1.0 μg/mL), triptolide (1.0 μg/mL), and honokiol (10.0 μg/mL) were introduced and incubated for an additional 48 h. Subsequently, HepG2 cells were trypsinized, eluted, and collected for use in the Western blot assay. Concurrently, HepG2 cells were cultured on TCP and subjected to simultaneous exposure to the aforementioned three drugs. These treated cells were also collected for further analysis. For reference, cells initially utilized for inoculation served as the control group. To extract the total protein from the cells, all groups were rinsed with precooled PBS and then suspended in a standard radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer. Subsequently, the protein samples were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel and subsequently transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Following this, the nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for a duration of 1.5 h, and subsequently, it was incubated with primary antibodies, specifically rabbit polyclonal anti-E-cadherin and mouse monoclonal antivimentin (obtained from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at 4 °C overnight. After washing in an appropriate buffer, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for an additional 2 h. Immunoreactive proteins were then visualized using a Gel Doc XR imaging system (Bio-Rad, Lab, Hercules, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise mentioned, all of the experiments were conducted in triplicate. The presented results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were carried out using the Student’s t-test, with statistical significance designated as p < 0.05.

Results

Preparation and Characterization of the Liver-Decellularized Extracellular Matrix

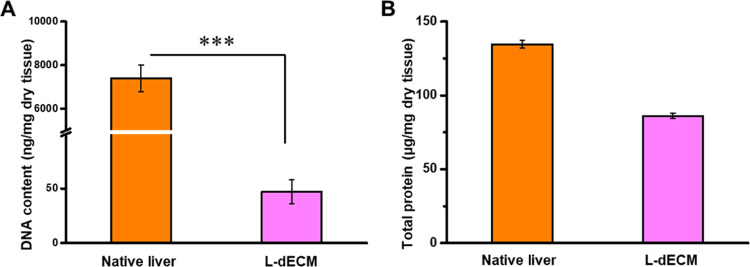

Various methods are available for the preparation of decellularized extracellular matrices, encompassing physical, chemical, and enzymatic approaches.13 Chemical methods disintegrate cell membranes or facilitate the hydrolysis of specific biomolecules, effectively eliminating cellular constituents. Detergents, commonly employed for tissue decellularization, operate by disrupting cell membranes and degrading intracellular DNA. In this particular investigation, Triton X-100, a nonionic surfactant, was employed to dismantle and cleanse cellular components, and subsequent DNase treatment was administered to eliminate residual DNA. As illustrated in Figure 2A, the SEM images demonstrate the presence of fibrous and porous structures within the L-dECM scaffold following decellularization, in contrast to the dense structure observed in native liver tissue. Moreover, H&E staining images in Figure 2B reveal the absence of discernible cellular elements within the L-dECM. Additionally, as depicted in Figure 2C, Masson’s trichrome staining exhibits blue markings in both native liver tissue and the L-dECM scaffold, affirming the preservation of collagen. To further verify the removal of DNA residue and protein content within the L-dECM scaffold, DNA and total protein quantification was conducted using specific kits. The results demonstrate a significant reduction in DNA content after decellularization, with only approximately 47.2 ± 10.7 ng/mg DNA remaining in the dry weight, underscoring the highly effective DNA removal capacity of the L-dECM (Figure 3A). Furthermore, total protein analysis reveals a decrease from 134.7 ± 2.6 to 86.1 ± 1.9 μg/mg following decellularization (Figure 3B). This decline may be attributed to the removal of proteins from cell components and the inevitable elution of some proteins from the extracellular matrix.

Figure 2.

Characterization of L-dECM. (A) Typical SEM image, (B) H&E staining, and (C) Masson’s trichrome staining of native liver tissue and the L-dECM scaffold.

Figure 3.

(A) Residual DNA content and (B) total protein analysis of native liver tissue and the L-dECM scaffold.

The ECM serves as a critical source of structural and mechanical support that is essential for cell survival. More significantly, the ECM encompasses functional proteins and growth factors that play pivotal roles in cell bioregulation, adhesion, and aggregation, attributes often lacking in many synthetic materials.27,28 Decellularization, in particular, is instrumental in creating an accommodating growth environment for the recellularization of ECM-based scaffolds, more faithfully mimicking the physiological state of cells within native tissues thanks to the influence of ECM components. Moreover, meticulous control of the cellular components within ECM materials is imperative. Given its immunogenic potential, maintaining DNA content at or below 50 ng/mg ensures in vitro compatibility and minimal immunological responses in vivo. Consequently, the generated L-dECM scaffold appears well-suited for the subsequent development of a tumor organoid-like tissue model.

Proliferation of HepG2 Cells in a Tumor Organoid-like Tissue Model

HepG2 cells were cultivated on L-dECM to establish tumor organoid-like tissue, and cell proliferation was assessed. The morphological characteristics of HepG2 cells were observed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM), revealing that cells incubated on TCP exhibited a predominantly spindle-shaped morphology (Figure 4A), while those growing in the organoid-like tissue exhibited primarily spherical shapes (Figure 4B). In general, the fate and function of cells, encompassing parameters such as cell adhesion, proliferation, and morphology, are intricately linked to the microenvironment in which cells are situated. This includes factors such as geometric shape, substrate hardness, chemical composition of the ECM, and the charge of the contact materials.29 Several prior studies have underscored the impact of the ECM on cell morphology through the modulation of cell signaling pathways, particularly in the context of tumor development and metastasis.30,31 Hence, the distinct morphologies observed in the growth of HepG2 cells on TCP and in organoid-like tissue may not be solely attributed to mechanical hardness. Rather, the ECM components play a pivotal role in influencing the biochemical and molecular aspects of these cells. Furthermore, as indicated in Figure 4C, the H&E staining of the tumor organoid-like tissue demonstrates that the scaffold effectively supports the robust proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells.

Figure 4.

Typical SEM image of HepG2 cell growth on (A) TCP and (B) organoid-like tissue. (C) H&E staining of tumor organoid-like tissue. (D) Proliferation of HepG2 cells on TCP and organoid-like tissue within 7 days.

Additionally, we employed the CCK-8 assay to evaluate the proliferation of HepG2 cells. As depicted in Figure 4D, HepG2 cells exhibited rapid growth during the initial 3 days of culture on TCP, with a more than 3-fold increase compared to day 1, after which cell numbers gradually declined. This observed decline can be attributed to the limited spatial constraints of 2D culture, restricting cell expansion and leading to apoptosis. Conversely, HepG2 cells displayed notably accelerated growth within the tumor organoid-like tissue. Their proliferation rate was 149.4% faster than that of cells cultured in 2D over the course of the initial 3 days, and cell viability continued to increase over a span of 7 days. In the study by Mazza et al., the implantation of human cell lines on decellularized human liver scaffolds demonstrated prolonged cell proliferation and robust cell viability over an extended period.32 These results collectively indicate that the L-dECM scaffold, functioning as a substrate for organoid-like tissue, creates a conducive environment for robust cell growth, offering an extended cell growth cycle that is well-suited for drug screening purposes.

Hepatic Function Evaluation of HepG2 Cells

The hepatic function of HepG2 cells was assessed by evaluating the secretion levels of albumin and urea expression levels in the culture media. As shown in Figure 5A, the quantity of albumin secreted by HepG2 cells cultured on TCP experienced a gradual increase within the initial 4 days, reaching a peak of 21.7 ± 6.5 μg/106 cells per day, subsequently exhibiting a gradual decline to 16.7 ± 3.6 μg/106 cells per day in the subsequent days. In contrast to the TCP culture, HepG2 cells within the tumor organoid-like tissue exhibited heightened albumin secretion. Initially, they produced 14.3 ± 6.2 μg/106 cells per day (as opposed to 10.6 ± 3.4 μg/106 cells per day on the culture board), after which albumin secretion steadily increased to 27.35 ± 7.8 μg/106 cells per day within the initial 4 days, maintaining a more consistent albumin secretion profile (p < 0.05). Figure 5B shows the quantity of urea production by HepG2 cells. Cells within the organoid-like tissue exhibited notably higher urea secretion (approximately 9.9 ± 2.6 μg/106 cells per day) compared to cells grown on TCP. Urea secretion leveled off after 5 days in the organoid-like tissue, whereas cells on TCP reached 5.4 ± 1.1 μg/106 cells per day after 3 days and subsequently displayed declining secretion levels (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that HepG2 cell growth within the organoid-like tissue offers enhanced stability and maintains specific functionality more effectively than TCP culture. In addition, as observed in Figure 5C,D, all three drugs (DOX, triptolide, and honokiol) resulted in reduced albumin secretion and urea synthesis by HepG2 cells in both the organoid-like tissue and TCP culture. Notably, there were no significant distinctions among the three drugs with respect to their effects on albumin secretion and urea synthesis.

Figure 5.

(A) albumin secretion and (B) urea synthesis of HepG2 cells after culture on TCP and in the tumor organoid-like tissue model within 7 days. (C) Albumin secretion and (D) urea synthesis of HepG2 cells during drug treatment. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 compared with other groups.

Cytotoxicity Assessment of Drugs in Tumor Organoid-like Tissue

DOX is an anthraquinone compound widely utilized for the treatment of various types of cancer. DOX’s antineoplastic action is primarily characterized by two fundamental mechanisms: first, the inhibition of DNA and RNA synthesis through the disruption of replication and transcriptional processes, and second, the generation of iron-mediated free radicals that induce oxidative damage to cell membranes, proteins, and DNA.33Figure 6A illustrates that both HepG2 cells cultured on tissue culture plates (TCPs) and within the tumor organoid-like tissue display DOX concentration-dependent cytotoxicity, exhibiting IC50 values of approximately 0.65 and 2.82 μg/mL, respectively. Remarkably, at higher DOX concentrations (greater than 1 μg/mL), TCP-cultured cells exhibit notably higher levels of cytotoxicity (p < 0.05). Notably, HepG2 cell growth within the tumor organoid-like tissue demonstrates considerably lower sensitivity to DOX in comparison to TCP culture.

Figure 6.

Dose-dependent cell viability after 72 h of treatment for cytotoxicity assessment of (A) DOX, (B) triptolide, and (C) honokiol. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 compared with other groups.

Furthermore, we conducted separate evaluations of the cytotoxicity of two other compounds, triptolide and honokiol, both derived from TCM, using distinct cellular models. Triptolide, a diterpenoid compound sourced from the plant Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F, has been extensively investigated in clinical research and applications, demonstrating unique biological activities, including immunosuppression and antifertility effects.34 Triptolide has also exhibited antitumor properties, manifesting as the inhibition of tumor proliferation, invasion, migration, and induction of cellular apoptosis.35 Notably, studies by Chen et al. reported that triptolide inhibited hepatoma cell viability and induced apoptosis by activating the tumor suppressor gene p53.36 As shown in Figure 6B, our investigation explored the impact of varying concentrations of triptolide on the viability of HepG2 cells. The results reveal increased cytotoxicity in both TCP culture and tumor organoid-like tissue models with escalating triptolide concentrations. However, cells cultured within the tumor organoid-like tissue demonstrated reduced sensitivity to triptolide, displaying an IC50 value of 0.98 μg/mL, as opposed to an IC50 value of 0.73 μg/mL in TCP culture. Honokiol, another natural compound extracted from Magnolia officinalis, is known for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antitumor properties.37 In Figure 6C, the cytotoxicity of honokiol toward cancer cells was assessed under different culture conditions. The IC50 value for honokiol in 2D culture was 7.41 μg/mL, whereas cells growing in the tumor organoid-like tissue exhibited an IC50 value of 9.74 μg/mL.

Evaluation of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Markers

EMT represents a cellular process during which cells undergo a transition from epithelial characteristics to mesenchymal characteristics. This transition is molecularly characterized by the downregulation of E-cadherin and the upregulation of vimentin. To evaluate the expression levels of E-cadherin and vimentin in HepG2 cells, we conducted a Western blotting assay. As seen in Figure 7A, we assessed the profiles of E-cadherin expression in cells cultured on TCP, within the tumor organoid-like tissue model, and subsequent to drug treatments. The outcomes indicated that HepG2 cells in the tumor organoid-like tissue model exhibited suppressed E-cadherin expression, with no significant differences observed between cells grown on TCP and the original cells. Figure 7B summarizes the alterations in the E-cadherin expression for each cell group in relation to the original cells. Cells cultivated within the tumor organoid-like tissue downregulated their E-cadherin protein expression by approximately 13.3%. Additionally, following triptolide treatment, E-cadherin expression in cells cultured on TCP increased by 11.4%. In contrast, cells within the tumor organoid-like tissue model only exhibited a marginal decrease of 2.5%, suggesting that triptolide could effectively reverse the downregulation of E-cadherin expression (p < 0.05). Notably, honokiol also upregulated E-cadherin expression in cells cultured on TCP. Conversely, the downregulation of protein expression within the tumor organoid-like tissue model was only slightly mitigated. Furthermore, DOX exhibited no discernible effect on protein expression in cells cultured under both TCP and organoid-like tissue conditions. The results pertaining to E-cadherin expression suggest that cells cultured in the tumor organoid-like tissue model undergo a loss of epithelial characteristics, and triptolide significantly counteracts this trend. The evaluation of the mesenchymal marker, vimentin, is depicted in Figure 7C,D. Notably, it was confirmed that cells cultured within the tumor organoid-like tissue model displayed significantly higher vimentin expression compared to those cultured on TCP, indicative of L-dECM’s promotion of mesenchymal characteristics. Vimentin expression in the tumor organoid-like tissue model exhibited a 19.4% increase compared with the original cells, while cells cultured on TCP showed minimal changes (Figure 6D). Triptolide and honokiol, on the other hand, downregulated vimentin expression in cells cultured on TCP and significantly reduced the upregulation of vimentin in cells cultured on the ECM. However, DOX had a limited impact on vimentin expression in cells under both culture conditions.

Figure 7.

Western blot analysis of (A) E-cadherin expression and (B) quantification protein expression, (C) vimentin expression, and (D) quantification protein expression in HepG2 cells cultured on TCP or tumor organoid-like tissue with triptolide, honokiol, and DOX treatment. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 compared with other groups.

Conclusions

The study explores the recellularization of liver-decellularized extracellular matrix (L-dECM) scaffolds with HepG2 cells as an in vitro model for screening antitumor agents. This tumor organoid-like tissue model not only supports robust cell growth but also enhances albumin secretion and urea synthesis compared with traditional TCP culture, underscoring its superior ability to maintain cell function. Furthermore, this tumor organoid-like tissue model induces the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in HepG2 cells, a phenomenon that is effectively reversed by triptolide and honokiol, while DOX demonstrates no such effect. Notably, the cytotoxicities of triptolide and honokiol toward HepG2 cells cultured on TCP are not significantly higher than those in the tumor organoid-like tissue model, respectively. However, the cytotoxicity of DOX toward HepG2 cells on TCP is significantly higher than that in the tumor organoid-like tissue model. This divergence can be attributed to drug resistance induced by EMT in tumor cells. Through the utilization of the tumor organoid-like tissue model, a more accurate investigation of the EMT process in a tissue environment is made possible, enabling a comprehensive exploration of the impact of drugs on EMT and the discovery of more effective anticancer agents.

Discussion

In the current study, the preparation of L-dECM scaffolds through the decellularization of liver tissues has enabled the effective establishment of an organoid-like tissue model with HepG2 cells. These models offer distinct advantages. First, the L-dECM scaffolds provide an accommodating environment for the growth of liver cancer cells, better preserving the unique functions of HepG2 cells compared to traditional TCP cultures. Additionally, during the drug screening process, the tumor organoid-like tissue closely mimics the biological characteristics of tumor cells within the tissue, demonstrating variable resistance levels to different drugs.

EMT signifies the transformation of polarized epithelial cells into motile cells, a process characterized by the loss of epithelial properties and the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics.38 EMT is typically initiated and activated in response to signals from the surrounding cellular environment during tumorigenesis, and it is closely associated with tumor invasion and metastasis.39 The influence of the ECM on the EMT process in tumors holds substantial significance in tumor development, invasion, and the acquisition of chemoresistance.40 Therefore, cell–ECM interactions and the induced EMT effects must be taken into consideration when evaluating drug screening of cell models. It has been reported that matrices mimicking the tumorigenic environment induce EMT in colorectal tumor cells and modulate drug efflux transporters, thereby contributing to the acquisition of resistance to 5-fluorouracil.40 Various biochemical and biophysical factors within the tumor microenvironment can regulate the EMT process. Yang et al. summarized the influence of tumor microenvironment factors, including ECM, stromal cells, and hypoxia, on EMT.41 ECM constitutes a pivotal component of the tumor microenvironment, with proteins such as collagen, hyaluronic acid, and fibronectin participating in downstream biochemical signal activation of the EMT process, thereby posing risks to tumor development and progression. In our current study, we observed that HepG2 cells cultured in the tumor organoid-like tissue model exhibited reduced E-cadherin expression and increased vimentin expression in comparison to cells grown on TCP (Figure 7B,D). This observation suggests that L-dECM scaffolds promoted the EMT process in tumor cells. Such effects may be attributed to the composition or structural influence of L-dECM on cell signaling, which more faithfully simulates the microenvironment, in which cells grow within the tissue. Given the significance of the EMT process in tumor cells, exploring EMT regulators is an attractive avenue for research, despite the dearth of relevant drugs.42 In our study, DOX, a commonly used broad-spectrum antitumor drug, proved ineffective in reversing the EMT in HepG2 cells. In contrast, the traditional Chinese medicine component, triptolide, exhibited significant efficacy in reversing the EMT in tumor cells, while honokiol also demonstrated an effect second only to triptolide. A prior report by Zhao et al. indicated that triptolide inhibits ovarian cancer by suppressing matrix metalloproteinase 7 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 while upregulating the expression of E-cadherin.43 Therefore, the L-dECM scaffold emerges as a promising tool to more accurately simulate the microenvironment for cell growth and to explore the tumor EMT process while evaluating the effects of various drugs on reversing the EMT.

Upon further analysis, the tumor organoid-like tissue model was found to promote the cellular EMT process, while two of the drugs investigated exhibited the capability to reverse this transition with DOX displaying limited effectiveness. The observed disparities could be attributed to the varying cytotoxicity of these drugs toward HepG2 cells within different growth environments. The ability of triptolide and honokiol to reverse the EMT effect mitigated these differences in cytotoxicity. The substantial divergence in DOX’s cytotoxicity between HepG2 cells cultured on L-dECM scaffolds and those on TCP might be linked to resistance arising from the EMT in cells.41 As such, the tumor organoid-like tissue model stands as a promising platform for the comprehensive exploration of antitumor drug toxicity and the dynamics of EMT progression in tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Anti-infective Agent Creation Engineering Research Centre of Sichuan Province Program (AAC2023001), the Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Southwestern Chinese Medicine Resources (SKLTCM202209), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2021YFH0169), and Chengdu University New Faculty Start-up Fund in China (2081921097).

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Shi J. J.; Kantoff P. W.; Wooster R.; Farokhzad O. C. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 20–37. 10.1038/nrc.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Kankala R. K.; Long L.; Xie S.; Chen A.; Zou L. Current understanding of passive and active targeting nanomedicines to enhance tumor accumulation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 481, 215051 10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Kankala R. K.; Yang Z.; Li W.; Xie S.; Li H.; Chen A. Z.; Zou L. Antibody-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, challenges, and prospects. Theranostics 2022, 12, 3719–3746. 10.7150/thno.72594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R. K. Phase II and phase III failures: 2013–2015. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15, 817–818. 10.1038/nrd.2016.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii Y.; Furukawa T.; Waki A.; Okuyama H.; Inoue M.; Itoh M.; Zhang M. R.; Wakizaka H.; Sogawa C.; Kiyono Y.; et al. High-throughput screening with nanoimprinting 3D culture for efficient drug development by mimicking the tumor environment. Biomaterials 2015, 51, 278–289. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J.; Lei D.; Chen M.; Ran P.; Li X. Engineering HepG2 spheroids with injectable fiber fragments as predictable models for drug metabolism and tumor infiltration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2020, 108, 3331–3344. 10.1002/jbm.b.34669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M.; Gao Q.; Fu J.; Chen Z.; He Y. Bioprinting of novel 3D tumor array chip for drug screening. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2020, 3, 175–188. 10.1007/s42242-020-00078-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Chen L.-F.; Wang Y.; Duan Y.-Y.; Luo S.-C.; Zhang J.-T.; Kankala R. K.; Wang S.-B.; Chen A.-Z. Modeling dECM-based inflammatory cartilage microtissues in vitro for drug screening. Composites, Part B 2023, 250, 110437 10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weng G.; Tao J.; Liu Y.; Qiu J.; Su D.; Wang R.; Luo W.; Zhang T. Organoid: Bridging the gap between basic research and clinical practice. Cancer Lett. 2023, 572, 216353 10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooft S. N.; Weeber F.; Schipper L.; Dijkstra K. K.; McLean C. M.; Kaing S.; van de Haar J.; Prevoo W.; van Werkhoven E.; Snaebjornsson P.; et al. Prospective experimental treatment of colorectal cancer patients based on organoid drug responses. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100103 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny P. A.; Lee G. Y.; Myers C. A.; Neve R. M.; Semeiks J. R.; Spellman P. T.; Lorenz K.; Lee E. H.; Barcellos-Hoff M. H.; Petersen O. W.; et al. The morphologies of breast cancer cell lines in three-dimensional assays correlate with their profiles of gene expression. Mol. Oncol. 2007, 1, 84–96. 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Wu Y.; Wang Z.; Liu Y.; Yu J.; Wang W.; Chen S.; Wu W.; Wang J.; Qian G.; He A. Standardization of organoid culture in cancer research. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 14375–14386. 10.1002/cam4.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. S.; Das S.; Jang J.; Cho D. W. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-based Bioinks for Engineering Tissue- and Organ-specific Microenvironments. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10608–10661. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Chen X.; Hong H.; Hu R.; Liu J.; Liu C. Decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds: Recent trends and emerging strategies in tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 10, 15–31. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzanakakis G.; Kavasi R. M.; Voudouri K.; Berdiaki A.; Spyridaki I.; Tsatsakis A.; Nikitovic D. Role of the extracellular matrix in cancer-associated epithelial to mesenchymal transition phenomenon. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 368–381. 10.1002/dvdy.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.-Y.; Fu C.-P.; Li X.-Y.; Lu X.-C.; Hu L.-G.; Kankala R. K.; Wang S.-B.; Chen A.-Z. Three-dimensional bioprinting of decellularized extracellular matrix-based bioinks for tissue engineering. Molecules 2022, 27, 3442 10.3390/molecules27113442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirazad H.; Dadashpour M.; Zarghami N. Application of decellularized bone matrix as a bioscaffold in bone tissue engineering. J. Biol. Eng. 2022, 16, 1 10.1186/s13036-021-00282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaldiz B.; Saglam-Metiner P.; Yesil-Celiktas O. Decellularised extracellular matrix-based biomaterials for repair and regeneration of central nervous system. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2021, 23, e25 10.1017/erm.2021.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Ansari A.; Pierre V.; Young K.; Kothapalli C. R.; von Recum H. A.; Senyo S. E. Injectable extracellular matrix microparticles promote heart regeneration in mice with post-ischemic heart injury. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2022, 11, e2102265 10.1002/adhm.202102265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Kankala R. K.; Wang S.; Chen A. Decellularized extracellular matrix-based composite scaffolds for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Regener. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbad107 10.1093/rb/rbad107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh T.; Ahmed E.; Yu L.; Song S. H.; Park K. M.; Kwak H. H.; Woo H. M. Conjugating homogenized liver-extracellular matrix into decellularized hepatic scaffold for liver tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2020, 108, 1991–2004. 10.1002/jbm.a.36920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesh K.; Gupta V. K.; Durden B.; Garrido V.; Mateo-Victoriano B.; Lavania S. P.; Banerjee S. Therapy Resistance, Cancer Stem Cells and ECM in Cancer: The Matrix Reloaded. Cancers 2020, 12, 3067 10.3390/cancers12103067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira L. P.; Gaspar V. M.; Mendes L.; Duarte I. F.; Mano J. F. Organotypic 3D decellularized matrix tumor spheroids for high-throughput drug screening. Biomaterials 2021, 275, 120983 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet J. M.; Pinyol R.; Kelley R. K.; El-Khoueiry A.; Reeves H. L.; Wang X. W.; Gores G. J.; Villanueva A. Molecular pathogenesis and systemic therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 386–401. 10.1038/s43018-022-00357-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. W.; Talati C.; Kim R. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): beyond sorafenib-chemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 256–265. 10.21037/jgo.2016.09.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Li Y.; Zhang J.; Ji L.; Li M.; Sun X.; Feng H.; Yu Z.; Gao Y. Current Perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicines and Active Ingredients in the Therapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2022, 9, 41–56. 10.2147/JHC.S346047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura R. D.; Padalhin A. R.; Park C. M.; Lee B. T. Enhanced decellularization technique of porcine dermal ECM for tissue engineering applications. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2019, 104, 109841 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G.; Jiang S.; Li J.; Wei F.; Li X.; Ding Y.; Yang Z.; Sun Z.; Zha K.; Wang F.; et al. Cell-free decellularized cartilage extracellular matrix scaffolds combined with interleukin 4 promote osteochondral repair through immunomodulatory macrophages: In vitro and in vivo preclinical study. Acta Biomater. 2021, 127, 131–145. 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha K. J.; Hong J. M.; Cho D. W.; Kim D. S. Enhanced osteogenic fate and function of MC3T3-E1 cells on nanoengineered polystyrene surfaces with nanopillar and nanopore arrays. Biofabrication 2013, 5, 025007 10.1088/1758-5082/5/2/025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K. S.; Zhong X.; Low C. S. L.; Kanchanawong P. Self-supervised classification of subcellular morphometric phenotypes reveals extracellular matrix-specific morphological responses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15329 10.1038/s41598-022-19472-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi M.; Piperigkou Z.; Karamanos K. A.; Franchi L.; Masola V. Extracellular Matrix-Mediated Breast Cancer Cells Morphological Alterations, Invasiveness, and Microvesicles/Exosomes Release. Cells 2020, 9, 2031 10.3390/cells9092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza G.; Rombouts K.; Rennie Hall A.; Urbani L.; Vinh Luong T.; Al-Akkad W.; Longato L.; Brown D.; Maghsoudlou P.; Dhillon A. P.; et al. Decellularized human liver as a natural 3D-scaffold for liver bioengineering and transplantation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13079 10.1038/srep13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Hong G.; Liu Z.; Yang D.; Kankala R. K.; Wu W. Synergistic antitumor efficacy of doxorubicin and gambogic acid-encapsulated albumin nanocomposites. Colloids Surf., B 2020, 196, 111286 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W.; Liu B.; Xu H. T. Triptolide: Medicinal chemistry, chemical biology and clinical progress. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 176, 378–392. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Zhang X.; Tian X.; Shen C.; Zhang Q.; Zhang Y.; Wang Z.; Wang F.; Tao Y. Triptolide inhibits tumor growth by induction of cellular senescence. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 442–448. 10.3892/or.2016.5258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. Y.; Xiao L.; Wang D.; Ji Y. C.; Yang Y. P.; Ma R.; Chen X. H. Triptolide inhibits viability and induces apoptosis in liver cancer cells through activation of the tumor suppressor gene p53. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 50, 847–852. 10.3892/ijo.2017.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauf A.; Olatunde A.; Imran M.; Alhumaydhi F. A.; Aljohani A. S. M.; Khan S. A.; Uddin M. S.; Mitra S.; Bin Emran T.; Khayrullin M.; et al. Honokiol: A review of its pharmacological potential and therapeutic insights. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153647 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves D.; Calle Y. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Associated Invasive Adhesions in Solid and Haematological Tumours. Cells 2022, 11, 649 10.3390/cells11040649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Antin P.; Berx G.; Blanpain C.; Brabletz T.; Bronner M.; Campbell K.; Cano A.; Casanova J.; Christofori G.; et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 341–352. 10.1038/s41580-020-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiba T. An extracellular matrix (ECM) model at high malignant colorectal tumor increases chondroitin sulfate chains to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance acquisition. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 370, 571–578. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Hu Z.; Horta C. A.; Yang J. Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition by tumor microenvironmental signals and its implication in cancer therapeutics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 88, 46–66. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.; Ng A. S.; Cai S.; Li Q.; Yang L.; Kerr D. Novel therapeutic strategies: Targeting epithelial–mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e358–e368. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Yang Z.; Wang X.; Zhang X.; Wang M.; Wang Y.; Mei Q.; Wang Z. Triptolide inhibits ovarian cancer cell invasion by repression of matrix metalloproteinase 7 and 19 and upregulation of E-cadherin. Exp. Mol. Med. 2012, 44, 633–641. 10.3858/emm.2012.44.11.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]