Abstract

This study was conducted to explore the interaction between two plant-based antiplasmodial compounds, gartanin and friedelin, and bovine serum albumin (BSA). The objectives aimed to elucidate the binding characteristics, structural changes, and thermodynamic parameters associated with the interaction. Various methods were used including UV–vis, fluorescence, and circular dichroism spectroscopy, supported by molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. The results showed a concentration-dependent interaction between the antiplasmodial compounds and BSA, revealing changes in protein conformation and stability. The obtained results showed that the plant products bound with BSA through static quenching with moderate binding affinity (104 M–1) with BSA. Thermodynamic parameters and structural transitions calculated from spectroscopic methods revealed that hydrogen bond and van der Waals forces caused the partial conformational alteration in the secondary structure of BSA as the α-helical content decreased with an increase in β sheets, random coils, and other structures. Computational analysis provided insights into the binding sites and affinities. The study enhances our understanding of the molecular interactions between BSA protein and antiplamodial compounds obtained from plants, supporting the research of choosing, designing, and optimizing molecules for biomedical applications with a focus on selectively targeting their binding sites.

1. Introduction

Plants are a rich source of chemical compounds that have been used for centuries as medicines.1 In recent times, researchers in the field of drug discovery have shown a strong interest in natural products and their derivatives, extracted from both plants and microorganisms.2,3 Many plant-derived compounds have been identified as potential drugs for various diseases, including cancer, infectious diseases, inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases.4−9 One example is artemisinin, which is derived from Artemisia annua and has been used to treat malaria.10 Malaria is treatable yet one of the most devastating diseases, and several approaches have been taken to combat it.11,12 Studying the interaction of plant compounds with serum albumin can provide insights into the mechanism of action of these compounds and their potential as drug candidates. For instance, the binding affinity of a compound for serum albumin can be used as a predictor of its bioavailability and distribution in the body. Plant compounds, such as flavonoids,13 alkaloids,14 and terpenoids,15 have been shown to interact with serum albumin through various mechanisms, including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic forces. Understanding the interaction mechanisms can help optimize the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs and compounds and identify potential drug–drug interactions and adverse effects.

Gartanin is a xanthone derivative found in the pericarp of the mangosteen fruit16 and leaves of Garcinia mangostana.17 It exhibits various pharmacological activities, including antifungal, antioxidant, and anticancer properties against bladder and lung cancers.18 It has been identified as a potential antiplasmodial compound (IC50 value, 3.1 μM)19 due to its ability to inhibit the growth of the Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum) parasite, which is responsible for causing malaria in humans.20,21 Further, 8-deoxygartanin, a derivative of gartanin, showed to have potent antiplasmodial activity, with an IC50 (the concentration of a drug required to inhibit 50% of the parasite growth) value in the 7.2 to 23.6 μM range.22

Friedelin is another natural product, a triterpene found in many plants including Azima tetracantha leaves23 that exhibits a range of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiplasmodial, and antiviral properties, making it a promising candidate for drug development.24,25 It has been identified as a potential antiplasmodial compound due to its ability to inhibit the growth of the P. falciparum parasite. Friedelin has moderate to high antiplasmodial activity, with an IC50 value of 7.2 μM.22,26 These observations suggest that gartanin and friedelin may be promising candidates for developing new antiplasmodial drugs, though the mechanism of action of gartanin and friedelin is not yet fully understood.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is a globular protein, a type of serum albumin derived from bovine blood, and is one of the most abundant proteins in bovine serum.33 Serum albumin is the most abundant protein in human blood plasma and plays a crucial role in drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.27 For instance, HSA acts as drug carrier for many diseases including cancer, diabetes, inflammation, and cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, serum albumin is prescribed as a therapeutic agent and stabilizer as low serum albumin in COVID-19 infections has been associated with many incidences of kidney and cardiac injury, hypercoagulability, and encephalopathy leading to higher mortality.28 Understanding how drugs interact with serum albumin helps in predicting their pharmacokinetic properties, such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion.29,30 This knowledge is valuable for optimizing drug dosage, determining drug–drug interactions, and designing drug delivery systems.30 A reduced affinity of serum albumin for drugs with less efficacy may result in increased toxicity levels due to the increase in the free form of drug concentration. Therefore, the study of the interaction of any antidisease compound with serum albumin has significant implications for drug discovery and pharmacology.31,32 BSA has a molecular weight of approximately 66,500 Da and has 583 amino acid residues. It has a high degree of homology to human serum albumin, which makes it a suitable substitute for human serum albumin in various applications.34 It also has applications in drug delivery and gene therapy and as a cryoprotectant. BSA has several advantages over other proteins, including its high purity, stability, and low cost. It also has a long shelf life and can be easily modified or conjugated with other molecules. In addition, BSA can interact with certain drugs or other compounds, which can affect their pharmacokinetic properties.35−37 Several studies have been done to understand the binding mechanism of ligands with BSA.38−43

Understanding the interaction between plant-based antiplasmodial compounds and bovine serum albumin is crucial for drug discovery for several reasons. Such an understanding has profound implications for drug efficacy, safety, and overall therapeutic outcomes. This knowledge informs the design, development, and optimization of antiplasmodial drugs, making it an essential area of research in the fight against malaria.44 Sharma et al. studied the interaction of triazole-substituted 4-methyl-7-hydroxycoumarin derivatives (CUM1–4) with HSA and BSA employing ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis), fluorescence, and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and molecular docking methods.45 Javaheri-Ghezeldizaj et al. investigated the interaction between henna and BSA through several spectroscopic techniques, along with molecular docking approach.46

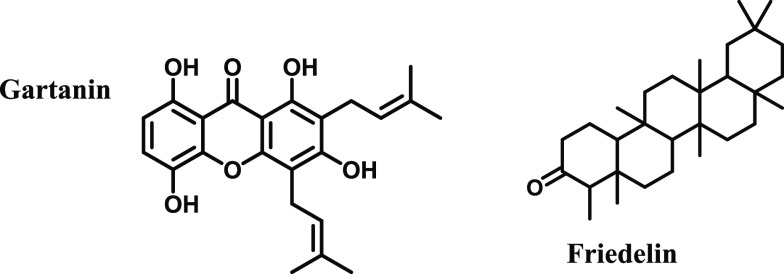

In the present study, the interaction of gartanin and friedelin (Figure 1) with bovine serum albumin has been studied using various techniques, including fluorescence spectroscopy, circular dichroism, and molecular docking. The study provides information on the binding site, binding constant, and conformational changes induced by the interaction of plant compounds with serum albumin. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation are also employed to investigate the interaction further. The results are analyzed comparatively, and conclusions were drawn accordingly.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of plant-derived compounds gartanin and friedelin.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Confirmation of Formation of the Complex

In general, the absorption spectrum of serum albumin demonstrates a peak around 280 nm. The peak near 280 nm is attributed to the presence of aromatic amino acid residues within the serum albumin structure, which is important in studying the change in protein conformation.35Figure 2A,B represents the absorption spectra of BSA in the absence and presence of gartanin and friedelin. Native BSA showed the absorption peak at 279 nm; however, no distinct absorbance by gartanin and friedelin alone was found as shown in Figure 2. On titrating the protein with gartanin, an increase in absorbance (hyperchromic shift) was observed indicating the complex formation between BSA and gartanin (Figure2A).47 This may be attributed to the gartanin’s increasing molar absorptivity caused by the disruption of the hydrogen bonds of each BSA molecule resulting in more access to its aromatic residues. On the other hand, a decrease in absorbance (hypochromic shift) around 280 nm with an increasing concentration of the friedelin was observed (Figure2B). Hypochromic shifts result from the friedelin’s decreasing molar absorptivity due to the formation of hydrogen bonds, causing less exposure of the aromatic residues of the protein molecules.48 Basically, changes in chemical structure lead to changes in the absorption spectrum of molecules. Overall, the regular changes in the absorption intensity on the addition of gartanin and friedelin indicate the formation of complexes. No bathochromic (red shift) or hypsochromic shift (blue shift) was observed in any case. The stability and conformational changes in the protein due to the binding of these molecules were further explored.

Figure 2.

UV titration of BSA (5 μm) at 279 nm with 2.46, 4.87, 7.22, 9.52, 11.76, 13.95, 16.09, 18.18, 20.22, and 22.22 μM of ligands (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin, at 298 K and 7.4 pH (absorbances of ligands alone are shown in cyan color near the X-axis).

2.2. Analysis of Binding Affinity and Thermodynamic Parameters

The experiment was carried out at two temperatures (298 and 308 K) in order to observe the temperature dependence of binding interaction and to fetch out the binding and thermodynamic parameters. The binding constant (Kb) values for the gartanin and friedelin interaction with the protein were calculated from the ratio of the slope to intercept of the double reciprocal plot (Figure 3A,B) between A0/(A –A0) versus 1/[compound] according to the Benesi–Hildebrand equation:49

| 1 |

Figure 3.

Double reciprocal plots of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin.

Values of Kb are summarized in Table 1. It shows that the Kbvalues decreased at higher temperatures, indicating that the quenching happened through the static mechanism. R2 is the measurement of how closely our curve matches the data that we have generated. The closer the value is to 1.00, the more accurately our curve represents the detector response. As shown in the table, all values of R2 are closer to one. Further, evaluation of thermodynamic parameters is essential to get information about the binding forces involved during protein and molecule interaction. These parameters were derived using the following equations.30

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where Kb1 and Kb2 represent binding constants of the complex at 298 and 308 K, respectively. R = 8.314 J K–1 mol–1, and T stands for temperature. Negative signs of ΔG indicate the spontaneity of the interactions of the natural compounds with BSA. Negative signs of ΔH and ΔS suggest that hydrogen bond and van der Waals interactions were the main interacting forces involved in the binding mechanism of both gartanin–BSA and friedelin–BSA complexes.50

Table 1. Binding Constant Kb, Gibbs Free Energy ΔG, Enthalpy ΔH, and Entropy ΔS Values and Interacting Forces Involved between BSA–Gartanin and BSA–Friedelin at Two Different Temperatures, 298 and 308 K, pH 7.4.

| complexes | temp. (K) | Kb(L mol–1) | R2 | ΔG(kJ mol–1) | ΔH(kJ mol–1) | ΔS(kJ mol–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gartanin–BSA | 298 | 1.46 × 104 | 0.99 | –24.28 | –42.16 | –0.06 |

| 308 | 0.84 × 104 | 0.99 | –23.68 | |||

| friedelin–BSA | 298 | 0.51 × 104 | 0.98 | –20.52 | –59.26 | –0.13 |

| 308 | 0.23 × 104 | 0.98 | –19.22 |

2.3. Fluorescence Probing of Secondary Structural Changes in Protein

Fluorescence intensity analysis of binding between molecules and protein is a quite sensitive phenomenon to probe the protein conformation and structure stability when changes occur in the microenvironment around protein fluorophores (tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine).51 Both static and dynamic quenching are two mechanisms that describe the interaction between a fluorophore (a molecule that emits light upon excitation) and a quencher (a molecule that reduces the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophore). Static quenching occurs when the fluorophore and the quencher (ligand) form a nonfluorescent complex, resulting in a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophore. A rise in temperature leads to a decrease in the stability of the protein–ligand complex, which ultimately results in a decrease in the quenching constant and also Stern–Volmer constant values.52,53 The quencher binds to the fluorophore with high affinity, and the fluorescence intensity is reduced even at low quencher concentrations.53 Dynamic quenching, on the other hand, occurs when the fluorophore and the quencher interact through collisions, resulting in a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophore. The quencher binds to the excited state of the fluorophore, leading to a transfer of energy from the excited state to the quencher, thereby reducing the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophore. Dynamic quenching is concentration-dependent and can be characterized by the Stern–Volmer equation, which relates the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophore to the concentration of the quencher. The choice of static or dynamic quenching mechanism depends on the nature of the fluorophore and the quencher, their concentrations, and the experimental conditions. In general, static quenching is preferred when the quencher has a high affinity for the fluorophore, whereas dynamic quenching is preferred when the quencher has a low affinity for the fluorophore and the concentration of the quencher is high.54

As shown, both gartanin (Figure 4A) and friedelin (Figure 4B) quenched the Trp of BSA protein at 343 nm. The fluorescence intensity of BSA decreased more significantly with an increase in the gartanin concentration than that of friedelin. There were no red or blue shifts observed in any cases here, signifying that the interaction of ligands with protein did not cause any alteration in the microenvironment around the Trp residues. The binding parameters were obtained through equations55 below and are summarized in Table 2.

| 5 |

| 6 |

where kq is the binding constant, n is the number of binding sites, and [Q] is the concentration of the quencher (gartanin and friedelin). R is the gas constant (8.341 × 10–3 kJ K–1 M–1), and T is the absolute temperature (K). From the values presented by Table 2, we can see that the Ksvvalue of gartanin–BSA obtained from the y-axis intercept of Stern–Volmer plots (Figure 4A inset) was 2.56 × 104 L mol–1, while that of friedelin–BSA was 1.27 × 104 L mol–1 (Figure 4B inset). A higher value of Ksv is suggestive of efficient quenching;56 thus, it can be concluded that gartanin quenched the fluorescence intensity of the protein more effectively than the friedelin. By knowing the lifetime of the fluorophore in the absence of a quencher (τo), which is 10–8 s for the native BSA, we can calculate the bimolecular quenching rate parameter (kq) using the following equation:56

| 7 |

Figure 4.

Fluorescence spectra of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin with BSA at 298 K and pH 7.4. Insets: Stern–Volmer plots.

Table 2. Ksv, Kb, kq, and n Values of Gartanin–BSA and Friedelin–BSA Complexes at 298 K.

| compounds | Ksv (L mol–1) | Kb (L mol–1) | kq | R2 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gartanin | 2.57 × 104 | 1.72 × 104 | 2.57 × 1012 | 0.99 | 1 |

| friedelin | 1.47 × 104 | 1.77 × 104 | 1.47 × 1012 | 0.99 | 1 |

Table 2 shows that obtained values of kqare greater than the maximum scatter collision quenching constant of quenchers with a biopolymer (2.0 × 1010 m–1 s–1). This indicates that fluorescence quenching of BSA by the natural compounds gartanin and friedelin happened through static quenching.57 The Kbvalues obtained through the y-axis intercept of modified Stern–Volmer plots (Figure5) are of the same order as obtained from UV spectroscopy earlier. The value of n is almost equal to one, suggesting that there is one binding site for each gartanin and friedelin on BSA.

Figure 5.

Modified Stern–Volmer plots of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin.

2.4. Fluorescence Lifetime Profile Analysis

Fluorescence lifetime measurement is known for its sensitivity in distinguishing between different quenching mechanisms. Its ability to detect interactions between ligands and proteins makes it a commonly employed method for precisely determining quenching mechanisms.58 Therefore, fluorescence lifetime measurements were conducted to validate the quenching results obtained by steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy. Figure 6A,B shows the fluorescence decay curves of BSA in the presence of gartanin and friedelin.

Figure 6.

Time-resolved fluorescence decays of BSA with increasing concentrations of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin at 298 K.

Triexponential fitting was done, which indicates that fluorescence from free BSA in PBS, at room temperature, decays through three distinct lifetimes (τ1, τ2, and τ3) with different contributions (α1, α2, and α3). All values are presented in Tables 3 and 4 for gartanin and friedelin, respectively. The average fluorescence lifetime (τavg) was calculated and used for the quenching analysis.

Table 3. Fluorescence Decay Profile of BSA with Different Concentrations of Gartanina.

| [gartanin] (μm) | τ1 | τ2 | τ3 | α1 | α2 | α3 | τavg | τ0 | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.08035 | 6.86603 | 0.81530 | 19.5% | 77.54% | 2.96% | 6.4 | 6.46 | 1.08 |

| 2.46 | 2.97079 | 6.87124 | 0.87935 | 26.45% | 67.78% | 5.77% | 6.2 | 6.46 | 1.04 |

| 9.52 | 3.0512 | 6.96661 | 0.80215 | 30.06% | 64.04% | 5.91% | 6.2 | 6.46 | 1.04 |

| 16.09 | 2.94543 | 6.88185 | 0.85474 | 28.92% | 64.86% | 6.22% | 6.1 | 6.46 | 1.00 |

| 22.22 | 3.25433 | 7.00397 | 0.99520 | 30.4% | 60.86% | 8.74% | 6.2 | 6.46 | 1.03 |

Triexponential fitting.

Table 4. Fluorescence Decay Profile of BSA with Different Concentrations of Friedelina.

| [friedelin] (μm) | τ1 | τ2 | τ3 | α1 | α2 | α3 | τavg | τ0 | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.08035 | 6.86603 | 0.815309 | 19.5% | 77.54% | 2.96% | 6.4 | 6.46 | 1.08 |

| 2.46 | 2.2687 | 5.69641 | 7.96207 | 8.67% | 55.5% | 35.83% | 6.6 | 6.46 | 1.06 |

| 9.52 | 2.6997 | 6.57619 | 14.2863 | 13.49% | 84.08% | 2.43% | 6.7 | 6.46 | 1.08 |

| 16.09 | 2.20993 | 6.35442 | 14.127 | 9.59% | 86.56% | 3.85% | 6.8 | 6.46 | 1.00 |

| 22.22 | 3.97844 | 7.09955 | 1.07545 | 25.73% | 71.9% | 2.37% | 6.5 | 6.46 | 1.01 |

Triexponential fitting.

It was observed that the addition of gartanin and friedelin did not change the fluorescence lifetime (τavg) of the fluorophore significantly, as values of τav remained almost constant at all additions of gartanin and friedelin concentrations. This clearly indicates the involvement of the static quenching mechanism for the gartanin and friedelin systems with BSA, which corresponds with the steady-state fluorescence results.59 A plot was constructed between τo/τ and gartanin and friedelin concentrations, and the resultant straight line further confirms the presence of static quenching rather than dynamic quenching (Figure 7A,B).

Figure 7.

Plots of τ0/τ as a function of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin at 298 K.

2.5. Microenvironmental and Conformational Analysis of the Protein

Synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy is employed to probe the change in the microenvironment around the fluorophores Trp (at Δλ = 60 nm) and Tyr (at Δλ = 15 nm) present in the protein upon binding with the molecules.60Figure 8A,B shows the synchronous spectra of BSA before and after binding with gartanin at Δλ = 60 and 15 nm. A decrease in fluorescence intensity with no shift in λmax was observed in all cases. Gartanin quenched the fluorescence intensity of both the residues of BSA. A similar effect was seen for the friedelin (Figure 8C,D).61 Moreover, the observation indicates that the microenvironment around tyrosine and tryptophan has not been affected by the compounds binding.62 Further conformational changes of the protein were investigated through three-dimensional fluorescence spectra as well as contour maps for the native and bound protein.

Figure 8.

Synchronous fluorescence spectra of BSA as a function of gartanin at (A) Δλ = 15 nm for Tyr and (B) Δλ = 60 nm for Trp and friedelin concentration at (C) Δλ = 15 nm for Tyr and (D) Δλ = 60 nm for Trp and at 298 K.

2.6. Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Obtaining 3D fluorescence data by simultaneously varying both excitation and emission wavelengths across a range offers valuable information about structural changes in the protein.43 The 3D spectra of BSA and BSA in complexation with gartanin and friedelin are shown in Figure9. In Figure 9A, peak A and peak B arise due to first-order Rayleigh scattering (λex = λem) and second-order Rayleigh scattering peak (λex = 2em), respectively. The interaction between gartanin and friedelin resulted in an increase in the fluorescence intensity of BSA at peak A because the formation of a complex enhanced the scattering effect. Peak 1 was obtained due to the π→π* transition of the aromatic amino acids, which is the characteristic fluorescence spectral behavior of Trp and Tyr residues, while peak 2, another fluorescence peak, was obtained due to the n→π* transition of the polypeptide backbone of the protein.63 The alterations in the fluorescence intensity of this peak are linked to modifications in the conformation of the polypeptide backbone or the surroundings of the polypeptide. Figure 9B,C shows that the fluorescence intensity of both peaks 1 and 2 decreased on the binding of gartanin and friedelin to BSA, which suggested the disruption of the polypeptide backbone structure in BSA induced by gartanin and friedelin. It resulted in a shift in the polarity and hydrophobicity around the Trp residue of BSA.

Figure 9.

3D fluorescence spectra and the respective contours of (A) BSA, (B) BSA–gartanin, and (C) BSA–friedelin.

2.7. Structural Analysis of BSA and BSA–Ligand Complexes by Far-UV Circular Dichroism

The conformation alteration was further checked by far-UV circular dichroism (CD) in the spectral region of 190 to 250 nm. CD is a useful technique for studying protein–drug binding because it provides information about changes in protein secondary structure upon drug binding.64 These changes can be used to infer information about the mechanism of drug binding and the stability of the drug–protein complex. The far-UV CD spectrum of BSA alone and BSA–gartanin/friedelin conjugates at pH 7.4 showed two negative minima at 208 and 222 nm indicating the presence of α-helical content. The literature has shown that the secondary structure of BSA contains almost 50 to 70% α-helices and 16 to 21% β-structures.65 As the compound gartanin and friedelin concentrations increased from 2.46 to 22.22 μM, a gradual decrease in the negative bands was observed toward the baseline acquiring lesser negative values (Figure 10A,B). The results clearly indicate a slight decline in the α-helical content of the protein and protein conjugates, evident of some conformational changes in BSA during interaction with gartanin and also with friedelin. This was further supported by the calculated α-helical percentage shown in Tables 5 and 6.The α-helical content of BSA reduced sharply from 67.08 to 59.46% on titration with gartanin. On the other hand, a decrease in the α-helical content of BSA was less on friedelin addition. Thus, the far-UV CD results suggest that the structure of the protein was less altered due to the binding of friedelin compared to gartanin. Overall, both of the plant products destabilized the secondary structure of BSA protein.

Figure 10.

Far-UV CD spectra of BSA in the absence and presence of various concentrations of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin.

Table 5. Percentage of the α-Helical Content in BSA Alone and with Gartanin.

| sample | α-helix % |

|---|---|

| BSA | 67.08 |

| BSA + gartanin | 69.12 |

| BSA + gartanin | 64.26 |

| BSA + gartanin | 59.46 |

Table 6. Percentage of the α-Helical Content in BSA Alone and with Friedelin.

| sample | α-helix % |

|---|---|

| BSA | 67.08 |

| BSA + friedelin | 66.38 |

| BSA + friedelin | 64.17 |

| BSA + friedelin | 61.65 |

2.8. In Silico and Computational Analysis

2.8.1. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking is a computer-based technique employed to forecast how a small-molecule ligand binds to a target protein as well as to estimate the strength of this binding. The goal of this technique is to identify the most favorable conformation of the ligand within the binding site of the protein and to calculate the binding energy between the two molecules. Figure 11 represents the docked structure of gartanin with BSA (Figure 11A) along with the diagram showing interacting residues of the protein (Figure 11B) and also the 2D representation of the BSA–gartanin complex (Figure 11C). Similarly, Figure 12 represents the docked structure of friedelin with BSA (Figure 12A) along with the diagram showing interacting residues of the protein (Figure 12B) and also the 2D representation of the BSA–gartanin complex (Figure 12C). The pKi, the negative decimal logarithm of the inhibition constant, was calculated from the ΔG parameter while using the following formula:

where ΔG is the binding affinity (kcal mol–1), R (gas constant) is 1.98 cal (mol K)−1, T (room temperature) is 298.15 K, and Kipred is the predicted inhibitory constant. The ligand efficiency (LE) is a commonly applied parameter for selecting favorable ligands by comparing the values of the average binding energy per atom. The following formula was applied to calculate LE:

where LE is the ligand efficiency (kcal mol–1 non-H atom–1), ΔG is binding affinity (kcal mol–1), and N is the number of nonhydrogen atoms in the ligand. Gartanin has occupied subdomain IIA with a binding score of −9.2 kcal/mol, where Trp is also found, while friedelin bound in the binding pocket of subdomain IIB with a binding score of −7.9 kcal/mol. Table 7 shows the affinity profile of both ligands with the protein. Here, the data show that gartanin showed a higher ligand efficiency with a higher pKi value than friedelin.

Figure 11.

Interaction between BSA and gartanin: (A) docked structure of the BSA–gartanin complex and (B) interacting residues of BSA with gartanin; (C) 2D representation of the same complex.

Figure 12.

Interaction between BSA and friedelin: (A) docked structure of the BSA–friedelin complex and (B) interacting residues of BSA with gartanin. (C) 2D representation of the same complex.

Table 7. Binding Affinity Profiles of Gartanin and Friedelin with BSA.

| ligand | binding free energy (kcal/mol) | pKi | ligand efficiency (kcal/mol/non-H atom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gartanin | –9.2 | 6.75 | 0.2968 |

| friedelin | –7.9 | 5.79 | 0.2724 |

2.8.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study

MD simulation plays a crucial role in the study of drug–protein binding. The binding of a drug to a protein is a complex process that involves multiple interactions between the drug molecule and the protein. MD simulation can provide a detailed understanding of these interactions and can help predict the binding affinity of a drug to a specific protein. We investigated the dynamic interactions between gartanin and friedelin with BSA using a 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation conducted with Desmond. To gauge the average change in the displacement of specific atoms in a given frame relative to a reference frame, we analyzed the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD).66 The root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) is employed to characterize local changes/fluctuations along the protein chain.67 The RMSD and RMSF plots of the native protein are shown in Figure 13A,B. In comparison with the apoprotein (Figure 13), a significant difference can be seen in the RMSD and RMSF values after binding with gartanin and friedelin (Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Plots of (A) RMSD and (B) RMSF of BSA.

Figure 14.

Plots of (A) RMSD of gartanin, (B) RMSD of friedelin, (C) RMSF of gartanin, and (D) RMSF of friedelin in complexation with BSA.

The RMSD curves for the Cα atoms of the protein with respect to the gartanin and friedelin were determined and plotted (Figure 14). At the left Y-axis, the RMSD evolution of BSA is shown. All protein frames are first aligned on the reference frame backbone, and the RMSD was calculated. Figure 14A shows that up to around 40 s, the structural conformation is not affected, but there was a fluctuation seen from 40 to 70 s after which it was stabilized again until 100 ns. The change of almost 4 Å is seen here, which is in an acceptable range for large, globular proteins like BSA.68 This suggests that the protein underwent some conformational changes in its Cα atoms leading. At the right Y-axis, the gartanin RMSD is shown, which indicates the stability of the ligand concerning the protein and its binding site. ‘Lig fit on prot’ represents the RMSD of gartanin after aligning the BSA–gartanin complex with the BSA backbone of the reference structure followed by measuring the RMSD of gartanin’s heavy atoms. The values observed were found to be almost the same as that of the BSA protein up to 80 ns after which a minor increase in values was observed, and then, it was stabilized and equilibrated until the end of simulation. Similarly, the RMSD values of BSA after interaction with friedelin (Figure 14B) showed a minor fluctuation of 2.4 Å. On the other hand, the RMSD values of friedelin decreased by 4 Å at around 60 ns and then stabilized until 100 ns. Overall, it was concluded that both gartanin and friedelin still remained folded in their initial binding sites throughout the simulation time period. Also, the impact of friedelin on protein’s conformation was less than that of the gartanin.

Figure 14C,D shows the ligand RMSF, which shows the gartanin and friedelin fluctuations broken down by atom with respect to the protein. The ligand RMSF may give insights into how ligand fragments interact with the protein and their entropic role in the binding event. The protein–ligand complex is first aligned on the protein backbone, and then, the ligand RMSF is measured on the ligand heavy atoms. On the plot, peaks in the data represent regions of the protein that exhibit the highest degree of fluctuation during the simulation. Usually, the tails, both the N-terminal and C-terminal regions, exhibit more pronounced fluctuations compared to other parts of the protein. On the other hand, α-helices and β strands fluctuate less than the loop regions as the former is usually more rigid than the unstructured part of the protein. Here, the green-colored vertical bars show the protein residues that interacted with gartanin and friedelin. The plot shows a significant number of interactions of gartanin (Figure 14C) and friedelin (Figure 14D) with various residues of the BSA protein. Particularly, in the case of gartanin, the interaction with protein residues is mostly at the lower fluctuation state of the ligand, which makes it more stable in comparison with the BSA–friedelin complex.

Furthermore, the interaction diagram between BSA and gartanin and friedelin categorized by type is shown in Figure 15. The stacked bar charts have been adjusted to account for variations over the entire trajectory. For example, the Asp129 residue of BSA protein maintained its hydrogen bonding and Lys20 maintained hydrophobic bonding with gartanin almost 30 and 97% of the simulation time, respectively (Figure 15A). While in the case of friedelin, only 15% of hydrogen bonding was maintained (by Lys439) (Figure 15B). Overall, it was concluded that gartanin exhibited significant and stable interaction with BSA without much affecting its conformational stability. This result was further supported by the protein–ligand contact timeline shown in Figure 16. It is the timeline representation of the interactions and contacts in which the upper panel shows the number of specific contacts that the protein made with the ligand in the trajectory frame. On the other hand, the bottom panel shows which residues of BSA interacted with the ligand in the trajectory frame. Gartanin was able to make up to 7–8 contacts during the simulation period (Figure 16A, top panel). Further, the darker shades indicate that some residues, like Lys20, made more than one specific contact with the gartanin (bottom panel). On the other hand, there were lesser contacts made by the friedelin as evident by both the top and bottom panels (Figure 16B, top and bottom panels). Most of the simulation time, there were zero contacts between the friedelin and BSA, which also supports the docking result mentioned above.

Figure 15.

Histograms of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin contacts with BSA residues throughout the trajectory.

Figure 16.

Representation of the contact timelines of (A) BSA–gartanin and (B) BSA–friedelin.

Upon binding with the protein, the ligand also undergoes several changes, and its properties may change. Changes in gartanin’s and friedelin’s properties are shown through the various parameters labeled from 1 to 6 in Figure 17A,B. RMSD (1) is the root-mean-square deviation, rGyr (2) is the radius of gyration (measures the “extendedness” of the ligand), intraHB (3) is the intramolecular H-bond, MolSA (4) is the molecular surface area (value equivalent to a van der Waals surface area), SASA (5) is the solvent-accessible surface area (accessible by a water molecule), and PSA (6) is the polar surface area (contributed only by oxygen and nitrogen atoms). As evident, the RMSD values of gartanin lie between 1.0 and 1.5 Å, while that of friedelin is far lesser (0.25 Å) and more stable with no significant fluctuation. Similar trends were observed in the case of rGyr, MolSA, SASA, and PSA. Only the intramolecular hydrogen bonds were not found in the case of friedelin, which indicates that there was no internal H-bond formed within the friedelin molecule during the whole simulation period.

Figure 17.

Representation of the ligand properties of (A) gartanin and (B) friedelin.

3. Conclusions

In this investigation, we explored the binding mechanisms of two natural antiplasmodial compounds, gartanin and friedelin, with the BSA protein. UV and fluorescence studies revealed the formation of stable complexes between these compounds and BSA through static quenching, which was further confirmed by time-resolved fluorescence calculation. Notably, a singular binding site was identified for both gartanin and friedelin on the BSA protein, exhibiting moderate binding affinities to the BSA protein.

Secondary structural changes in BSA revealed through CD, indicated by a decline in the α-helical content, were observed during interactions with gartanin and friedelin where the decline in gartanin’s α-helical percentage was more significant. This suggests a more nuanced impact on the protein’s structure due to gartanin than friedelin, providing insights into the potential structural alterations induced by these antiplasmodial compounds. The integration of computational analysis complemented our experimental findings by offering dynamic insights into the long-term behavior of the ligand–protein complexes, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of compound–protein interactions. Molecular docking showed that gartanin was found to form a significant number of interacting bonds with BSA including hydrogen bonding. This was supported by molecular dynamics simulations showing the interacting mechanism of these plant products with protein in a dynamic environment.

The implications of these findings extend beyond this study, providing valuable knowledge for advancing drug design, dosage optimization, and development within the realm of pharmacology. However, to recognize the complexity of these interactions, further research is imperative to unravel the full mechanistic details of these compounds. This ongoing exploration is essential for optimizing their therapeutic potential as antiplasmodial drugs, emphasizing the need for continued investigation into their mode of action and potential applications in clinical settings.

In summary, our study not only elucidates the compound–protein interactions, binding mechanisms, and structural changes induced by gartanin and friedelin but also underscores the potential of these natural compounds as promising candidates for antiplasmodial drug development.

4. Experimental Section

BSA (bovine serum albumin) protein (purity of each >98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; gartanin and friedelin were isolated, purified, and characterized by Prof. Mehtab Parveen, Aligarh Muslim University, India, and kept at 2–8° until use. A stock solution was prepared by dissolving the protein directly in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The absorbance of the solution was taken to determine the concentration using the molar absorption coefficient value of BSA (43,824 M–1 cm–1). Stock solutions of the compounds were prepared by dissolving these natural compounds into DMSO. A working solution of 5 μm concentration was prepared by the dilution method. Different concentrations of gartanin and friedelin (2.46–22.22 μM) were used for the interaction study. All solutions were stored in a refrigerator until use.

4.1. UV–Visible Spectroscopy

The UV–visible spectra were taken using an analytic Jena specord-210 spectrophotometer (Germany) equipped with a temperature-controlling Peltier system that maintained a uniform temperature throughout the cell. The slit width was set at 1 nm. The absorbance spectra of BSA (5 μm) and different concentrations of natural compounds were measured within a wavelength range of 200–500 nm, using a quartz cell with a path length of 1 cm.

4.2. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

The fluorescence spectra were recorded on a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Varian, USA) equipped with a 150 W xenon lamp and a Peltier system, using a 1.0 cm quartz cuvette at 298 K with both excitation and emission bandwidths fixed at 5 nm. The excitation of proteins was selected at 280 nm. Synchronous fluorescence spectra were obtained from the same spectrofluorometer setting the excitation and emission wavelength intervals Δλ = 15 nm and Δλ = 60 nm ranging from 250 to 310 nm, which provide characteristic information about tyrosine (Tyr) and tryptophan (Trp) residues, respectively. The 3D fluorescence spectra of pure BSA and natural compound–BSA complexes were measured using the same spectrofluorometer. The emission wavelength range was set as 200–500 nm, and the excitation wavelength was taken at 200–350 nm with an increment of 5 nm. The concentrations of BSA and each natural compound were 5 and 22.22 μM, respectively.

4.3. Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Time-resolved fluorescence (TRF) measurements were conducted by employing a single-photon counting spectrometer equipped with pulsed nanosecond LED excitation sources emitting at a wavelength of 280 nm, and the experiments were carried out at a temperature of 298 K. The spectrometer used for these measurements was manufactured by Horiba, Jobin Yvon, and IBH Ltd. in Glasgow, UK. The instrument’s response function was sequentially recorded using a scattering solution, and a time calibration of 114 ps per channel was applied. The data were then analyzed using a mathematical approach that involves summing exponentials and employing a nonlinear least-squares reconvolution analysis, using the following equation:

| 8 |

The pre-exponential factors (αi) were normalized to 1, and the errors were taken as three standard deviations. Chi-squared (χ2) values and weighted residuals were analyzed to judge the goodness of fit. TRF decays were analyzed by using IBH DAS6 software. The average fluorescence lifetimes (τav) for triexponential fittings were obtained by using the following equation:

| 9 |

where αi and τi are the relative contribution and lifetime of different components to the total decay, respectively.

4.4. Circular Dichroism

CD measurements were done in the wavelength range of 200–260 nm by a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter (Japan) with a 1 mm cell at 1 nm intervals. For each CD spectrum, three scans were taken, and their average was calculated for analyzing the results. The mean residual ellipticity (MRE) is a concentration-independent parameter, and it was obtained using the following equation:

Here, M0 represents the mean residue weight of the protein, θλ is the observed ellipticity in millidegrees at wavelength λ, C is the protein concentration (mg mL–1), and l is the path length of the cell in centimeter. The percentage of α-helical concentration in BSA was estimated based on the ellipticity values at 208 nm, using the equation:

4.5. Molecular Docking

In order to identify the binding sites and predict the ligand–protein binding energy, molecular docking was employed. The software used was InstaDock,69 which uses the Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) to generate various conformers of ligands. The implementation of LGA gives information regarding various interactions like electrostatic, van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and loss of entropy upon ligand binding and solvation. The 3D structure of BSA was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 4F5S). The docked images were created and visualized by using PyMOL and Discovery Studio.

4.6. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study

For molecular dynamics simulation, the Desmond module of Schrödinger release 2022-470 was employed on the Linux system to evaluate the protein’s binding interactions between the ligands and BSA protein. BSA (PDB ID 4F5S) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. The protein was prepared by a module of Schrödinger suite 2022-4. Simulation was carried out to verify the structural integrity of the protein complex using the optimized potentials for liquid simulations (OPLS4) force field at pH 7.4. A simulation lasting for 100 ns was conducted, beginning with the process of solvating the protein and the chosen complex by introducing water molecules. Boundaries for the complex were established by using an orthorhombic box. Na+ and Cl– charges were added to neutralize the charges and maintain a salt concentration of 0.15 m. The simulation was completed under 1.01325 bar pressure and a constant temperature of 300 K, with a mainline recording interval of 5 ps. The ligand interactions with different atoms were determined for each trajectory frame.

Acknowledgments

K.A. acknowledges the non-NET fellowship granted by UGC, Govt. of India. A.H. acknowledges the generous support from the researchers supporting project number RSPD2024R980, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Facilities provided by the Central Instrumentation Facility (CIF), JMI are highly acknowledged.

Author Contributions

K.A. performed the experiments and measurements; R.P. and M.A. were involved in planning and supervised the work, K.A. and S.A. processed the experimental data, performed the analysis and calculations, drafted the manuscript, designed the figures, and contributed to the interpretation of the results. H.T.A. and A.H. planned and carried out the simulations. K.A. and M.A. took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Parveen M.; Khan N. U.-D.; Achari B.; Dutta P. K. A triterpene from Garcinia mangostana. Phytochemistry 1991, 30 (1), 361–362. 10.1016/0031-9422(91)84157-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qadri H.; Haseeb Shah A.; Mudasir Ahmad S.; Alshehri B.; Almilaibary A.; Ahmad Mir M. Natural products and their semi-synthetic derivatives against antimicrobial-resistant human pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29 (9), 103376 10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Razek A. S.; El-Naggar M. E.; Allam A.; Morsy O. M.; Othman S. I. Microbial natural products in drug discovery. Processes 2020, 8 (4), 470. 10.3390/pr8040470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri R.; Coppo E.; Marchese A.; Daglia M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez E.; Nabavi S. F.; Nabavi S. M. Phytochemicals for human disease: An update on plant-derived compounds antibacterial activity. Microbiological research 2017, 196, 44–68. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzani R.; Salehi B.; Vitalini S.; Iriti M.; Zuñiga F. A.; Sharifi-Rad J.; Martorell M.; Martins N. Synergistic effects of plant derivatives and conventional chemotherapeutic agents: an update on the cancer perspective. Medicina 2019, 55 (4), 110. 10.3390/medicina55040110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutha R. E.; Tatiya A. U.; Surana S. J. Flavonoids as natural phenolic compounds and their role in therapeutics: An overview. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 1–13. 10.1186/s43094-020-00161-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubair N.; Rajagopal M.; Chinnappan S.; Abdullah N. B.; Fatima A. Review on the antibacterial mechanism of plant-derived compounds against multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR). Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 3663315. 10.1155/2021/3663315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Yao L. Antiviral effects of plant-derived essential oils and their components: an updated review. Molecules 2020, 25 (11), 2627. 10.3390/molecules25112627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran R.; Abrahamse H. Identifying plant-based natural medicine against oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2020, 2020, 8648742. 10.1155/2020/8648742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N.; Zhang Z.; Liao F.; Jiang T.; Tu Y. The birth of artemisinin. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2020, 216, 107658 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid M.; Singh S.; Egan T. J.; Joshi M. C. Structural-activity Relationship of Metallo-aminoquines as Next Generation Antimalarials. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2022, 22 (6), 436–472. 10.2174/1568026622666220105103751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin A.; Gupta S.; Mohammad T.; Shahi D.; Hussain A.; Alajmi M. F.; El-Seedi H. R.; Hassan I.; Singh S.; Abid M. Target-based virtual screening of natural compounds identifies a potent antimalarial with selective falcipain-2 inhibitory activity. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 13, 850176 10.3389/fphar.2022.850176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue P.; Zhang G.; Zhang J.; Ren L. Interaction of flavonoids with serum albumin: A Review. Current Protein and Peptide Science 2021, 22 (3), 217–227. 10.2174/1389203721666201109112220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi M.; Miroliaei M.; Taslimi P.; Moradi M. In silico analysis of the molecular interaction and bioavailability properties between some alkaloids and human serum albumin. Structural Chemistry 2022, 33 (4), 1199–1212. 10.1007/s11224-022-01925-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalchev K.; Hristova I.; Manova G.; Manov L. Interaction of the birch-bark terpenoids with human and bovine serum albumins. Acta Scientifica Naturalis 2022, 9 (3), 25–35. 10.2478/asn-2022-0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oetari R. A.; Hasriyani H.; Prayitno A.; Sahidin S. Gartanin compounds from extract ethanol pericarp mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana Linn.). Open Access Macedonian J. Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 3891. 10.3889/oamjms.2019.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen M.; Khan N. U.-d. Two xanthones from Garcinia mangostana. Phytochemistry 1988, 27 (11), 3694–3696. 10.1016/0031-9422(88)80804-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muchtaridi M.; Pratiwi R.; Alam G.; Rohman A. Analysis of gartanin in extract of mangosteen pericarp fruit (Garcinia mangostana L.) using spectrophotometric Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) method. Rasayan J. Chem. 2019, 12 (2), 874. 10.31788/RJC.2019.1225216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2023). PubChem Bioassay Record for AID 421809, Source: ChEMBL. Retrieved December 8, 2023 from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioassay/421809.

- Zelefack F.; Guilet D.; Fabre N.; Bayet C.; Chevalley S.; Ngouela S.; Lenta B. N.; Valentin A.; Tsamo E.; Dijoux-Franca M.-G. Cytotoxic and antiplasmodial xanthones from Pentadesma butyracea. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72 (5), 954–957. 10.1021/np8005953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiengsusuk A.; Chaijaroenkul W.; Na-Bangchang K. Antimalarial activities of medicinal plants and herbal formulations used in Thai traditional medicine. Parasitology Research 2013, 112, 1475–1481. 10.1007/s00436-013-3294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista R.; De Jesus Silva Júnior A.; De Oliveira A. B. Plant-derived antimalarial agents: new leads and efficient phytomedicines. Part II. Non-alkaloidal natural products. Molecules 2009, 14 (8), 3037–3072. 10.3390/molecules14083037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunil C.; Duraipandiyan V.; Ignacimuthu S.; Al-Dhabi N. A. Antioxidant, free radical scavenging and liver protective effects of friedelin isolated from Azima tetracantha Lam. leaves. Food chemistry 2013, 139 (1–4), 860–865. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi M. H.; El-Shiekh R. A.; El-Halawany A. M.; Abdel-Sattar E. Friedelin and 3β-Friedelinol: Pharmacological Activities. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2023, 886–900. 10.1007/s43450-023-00415-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malaník M.; Treml J.; Rjašková V.; Tížková K.; Kaucká P.; Kokoška L.; Kubatka P.; Šmejkal K. Maytenus macrocarpa (Ruiz & Pav.) Briq.: phytochemistry and pharmacological activity. Molecules 2019, 24 (12), 2288. 10.3390/molecules24122288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngouamegne E. T.; Fongang R. S.; Ngouela S.; Boyom F. F.; Rohmer M.; Tsamo E.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J. Endodesmiadiol, a friedelane triterpenoid, and other antiplasmodial compounds from Endodesmia calophylloides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56 (3), 374–377. 10.1248/cpb.56.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G.; Ahn S. N. Structure, enzymatic activities, glycation and therapeutic potential of human serum albumin: A natural cargo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 979–990. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G.; Ahn S. N. Roles of human serum albumin in prediction, diagnoses and treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 948–955. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaif N. A.; Wani T. A.; Bakheit A. H.; Zargar S. Multi-spectroscopic investigation, molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation of competitive interactions between flavonoids (quercetin and rutin) and sorafenib for binding to human serum albumin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 2451–2461. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeem K.; Irfan I.; Rashid Q.; Singh S.; Patel R.; Abid M.. Recent Updates on Interaction Studies and Drug Delivery of Antimalarials with Serum Albumin proteins. Curr. Med. Chem., 2023 10.2174/0929867330666230509121931. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Azeem K.; Ahmed M.; Uddin A.; Singh S.; Patel R.; Abid M.. Comparative Investigation on Interaction of Potent Antimalarials with Human Serum Albumin via Multispectroscopic and Computational Approaches. Luminescence, 2023 10.1002/bio.4590. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Azeem K.; Ahmed M.; Mohammad T.; Uddin A.; Shamsi A.; Hassan M. I.; Singh S.; Patel R.; Abid M. A multi-spectroscopic and computational simulations study to delineate the interaction between antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine and human serum albumin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 6377–6393. 10.1080/07391102.2022.2107077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan A.; Ostadrahimi A.; Jahanban-Esfahlan R.; Roufegarinejad L.; Tabibiazar M.; Amarowicz R. Recent developments in the detection of bovine serum albumin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 602–617. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketrat S.; Japrung D.; Pongprayoon P. Exploring how structural and dynamic properties of bovine and canine serum albumins differ from human serum albumin. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2020, 98, 107601 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Wang Y.; Tang L.; Liu H.; Chen W.; Zheng Z.; Zou G. Binding of puerarin to human serum albumin: a spectroscopic analysis and molecular docking. J. Fluoresc. 2008, 18 (2), 433–442. 10.1007/s10895-007-0283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui S.; Ameen F.; Kausar T.; Nayeem S. M.; Ur Rehman S.; Tabish M. Biophysical insight into the binding mechanism of doxofylline to bovine serum albumin: An in vitro and in silico approach. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2021, 249, 119296 10.1016/j.saa.2020.119296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar S.; Alamery S.; Bakheit A. H.; Wani T. A. Poziotinib and bovine serum albumin binding characterization and influence of quercetin, rutin, naringenin and sinapic acid on their binding interaction. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2020, 235, 118335 10.1016/j.saa.2020.118335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M. S.; Al-Lohedan H. A. Experimental and computational investigation on the molecular interactions of safranal with bovine serum albumin: Binding and anti-amyloidogenic efficacy of ligand. Journal of Molecular liquids 2019, 278, 385–393. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.01.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Wang X.; Bao Y.; Zhang C.; Liu H.; Li Z.; Chen M.; Wang C.; Guo Q.; Peng X. Molecular insight on the binding of monascin to bovine serum albumin (BSA) and its effect on antioxidant characteristics of monascin. Food chemistry 2020, 315, 126228 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A. J.; Kaur L.; Pathak M.; Singh A.; Verma P.; Singhal R.; Kumar V.; Ojha H. Spectroscopic studies of binding interactions of 2-chloroethylphenyl sulphide with bovine serum albumin. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117144 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.; Zhang Y.; Yu Q.; Shen Y.; Zheng Z.; Cheng J.; Zhang W.; Ye Y. Exploration of the binding between ellagic acid, a potentially risky food additive, and bovine serum albumin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110867 10.1016/j.fct.2019.110867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiquee M. A.; Parray M. u. d.; Mehdi S. H.; Alzahrani K. A.; Alshehri A. A.; Malik M. A.; Patel R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Delonix regia leaf extracts: In-vitro cytotoxicity and interaction studies with bovine serum albumin. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 242, 122493 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja B.; Kumari M.; Azam A.; Kumar A.; Abid M.; Patel R. Effect of triazole-tryptophan hybrid on the conformation stability of bovine serum albumin. Luminescence 2018, 33 (3), 464–474. 10.1002/bio.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma R.; Pan H.; Shen T.; Li P.; Chen Y.; Li Z.; Di X.; Wang S. Interaction of flavonoids from Woodwardia unigemmata with bovine serum albumin (BSA): Application of spectroscopic techniques and molecular modeling methods. Molecules 2017, 22 (8), 1317. 10.3390/molecules22081317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K.; Yadav P.; Sharma B.; Pandey M.; Awasthi S. K. Interaction of coumarin triazole analogs to serum albumins: Spectroscopic analysis and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Recog. 2020, 33 (6), e2834 10.1002/jmr.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaheri-Ghezeldizaj F.; Jafari A.; Mahmoudpour M.; Moghadaszadeh M.; Yekta R.; Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J. Binding process evaluation of bovine serum albumin and Lawsonia inermis (henna) through spectroscopic and molecular docking approaches. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 331, 115792 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui S.; Ameen F.; ur Rehman S.; Sarwar T.; Tabish M. Studying the interaction of drug/ligand with serum albumin. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 116200 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forster T. Intermolecular energy migration and fluorescence. Ann. Phys. 1948, 437, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Mir I. A.; Das K.; Akhter T.; Ranjan R.; Patel R.; Bohidar H. Eco-friendly synthesis of CuInS 2 and CuInS 2@ ZnS quantum dots and their effect on enzyme activity of lysozyme. RSC Adv. 2018, 8 (53), 30589–30599. 10.1039/C8RA04866E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross P. D.; Subramanian S. Thermodynamics of protein association reactions: forces contributing to stability. Biochemistry 1981, 20 (11), 3096–3102. 10.1021/bi00514a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusrat S.; Siddiqi M. K.; Zaman M.; Zaidi N.; Ajmal M. R.; Alam P.; Qadeer A.; Abdelhameed A. S.; Khan R. H. A comprehensive spectroscopic and computational investigation to probe the interaction of antineoplastic drug nordihydroguaiaretic acid with serum albumins. PLoS One 2016, 11 (7), e0158833 10.1371/journal.pone.0158833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G.; Baig M. H.; Jan A. T.; Ju Lee E.; Khan M. V.; Zaman M.; Farouk A. E.; Khan R. H.; Choi I. Binding of erucic acid with human serum albumin using a spectroscopic and molecular docking study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1572–1580. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G.; Lee E. J.; Ahmad K.; Baig M. H.; Choi I. Binding of tolperisone hydrochloride with human serum albumin: effects on the conformation, thermodynamics, and activity of HSA. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15 (4), 1445–1456. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samari F.; Hemmateenejad B.; Shamsipur M.; Rashidi M.; Samouei H. Affinity of two novel five-coordinated anticancer Pt (II) complexes to human and bovine serum albumins: a spectroscopic approach. Inorganic chemistry 2012, 51 (6), 3454–3464. 10.1021/ic202141g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlen M. H. The centenary of the Stern-Volmer equation of fluorescence quenching: From the single line plot to the SV quenching map. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews 2020, 42, 100338 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2019.100338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geethanjali H.; Nagaraja D.; Melavanki R.; Kusanur R. Fluorescence quenching of boronic acid derivatives by aniline in alcohols–a negative deviation from Stern–Volmer equation. J. Lumin. 2015, 167, 216–221. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2015.06.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petitpas I.; Bhattacharya A. A.; Twine S.; East M.; Curry S. Crystal structure analysis of warfarin binding to human serum albumin: anatomy of drug site I. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276 (25), 22804–22809. 10.1074/jbc.M100575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M.; Singh U. K.; Singh P.; Patel R. Effect of N-butyl-N-methyl-Morpholinium bromide ionic liquid on the conformation stability of human serum albumin. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2 (3), 1241–1249. 10.1002/slct.201601477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves O. A.; Sasidharan R.; dos Santos de Oliveira C. H.; Manju S. L.; Joy M.; Mathew B.; Netto-Ferreira J. C. In Vitro Study of the Interaction Between HSA and 4-Bromoindolylchalcone, a Potent Human MAO-B Inhibitor: Spectroscopic and Molecular Modeling Studies. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4 (3), 1007–1014. 10.1002/slct.201802665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-J.; Liu Y.; Zhang L.-X.; Zhao R.-M.; Qu S.-S. Studies of interaction between colchicine and bovine serum albumin by fluorescence quenching method. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 750 (1–3), 174–178. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2005.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R.; Singh B.; Sharma A.; Saraswat J.; Dohare N.; Parray M. u. d.; Siddiquee M. A.; Alanazi A. M.; Khan A. A. Interaction and esterase activity of albumin serums with orphenadrine: A spectroscopic and computational approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1239, 130522 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N.; Hadidi S.; Feizi F. Study on the interaction of antiviral drug ‘Tenofovir’with human serum albumin by spectral and molecular modeling methods. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2015, 138, 169–175. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M.; Maurya J. K.; Tasleem M.; Singh P.; Patel R. Probing HSA-ionic liquid interactions by spectroscopic and molecular docking methods. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2014, 138, 27–35. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G.; Ahmad E.; Zaidi N.; Fatima S.; Khan R. H. pH-Induced molten globule state of Rhizopus niveus lipase is more resistant against thermal and chemical denaturation than its native state. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 62, 487–499. 10.1007/s12013-011-9335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meti M. D.; Nandibewoor S. T.; Joshi S. D.; More U. A.; Chimatadar S. A. Binding interaction and conformational changes of human serum albumin with ranitidine studied by spectroscopic and time-resolved fluorescence methods. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2016, 13, 1325–1338. 10.1007/s13738-016-0847-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sargsyan K.; Grauffel C.; Lim C. How molecular size impacts RMSD applications in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13 (4), 1518–1524. 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.-B.; Xia Y.-L.; Dong G.-H.; Fu Y.-X.; Liu S.-Q. Exploring the cold-adaptation mechanism of serine hydroxymethyltransferase by comparative molecular dynamics simulations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22 (4), 1781. 10.3390/ijms22041781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M.; Kumari P.; Kashyap H. K. Structural adaptations in the bovine serum albumin protein in archetypal deep eutectic solvent reline and its aqueous mixtures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24 (9), 5627–5637. 10.1039/D1CP05829K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad T.; Mathur Y.; Hassan M. I. InstaDock: A single-click graphical user interface for molecular docking-based virtual high-throughput screening. Briefings Bioinf. 2021, 22 (4), bbaa279. 10.1093/bib/bbaa279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podduturi S.; Vemula D.; Singothu S.; Bhandari V. In-silico investigation of E8 surface protein of the monkeypox virus to identify potential therapeutic agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 1–14. 10.1080/07391102.2023.2245041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]