Abstract

Label-free quantitation (LFQ) was applied to proteome profiling of rat brain cortical development during the early postnatal period. Male and female rat brain extracts were prepared using a convenient, detergent-free sample preparation technique at postnatal days (PND) 2, 8, 15, and 22. The PND protein ratios were calculated using Proteome Discoverer, and the PND protein change profiles were constructed separately for male and female animals for key presynaptic, postsynaptic, and adhesion brain proteins. The profiles were compared to the analogous profiles assembled from the published mouse and rat cortex proteomic data, including the fractionated-synaptosome data. The PND protein-change trendlines, Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), and linear regression analysis of the statistically significant PND protein changes were used in the comparative analysis of the datasets. The analysis identified similarities and differences between the datasets. Importantly, there were significant similarities in the comparison of the rat cortex PND (current work) vs mouse (previously published) PND profiles, although in general, a lower abundance of synaptic proteins in mice than in rats was found. The male and female rat cortex PND profiles were expectedly almost identical (98–99% correlation by PCC), which also substantiated this LFQ nanoflow liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry approach.

Keywords: label-free quantitation, early postnatal brain cortex development, nanoflow-LC/MS, high-resolution MS

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

During the perinatal period, environmental stressors pose a potential threat to brain development because the brain undergoes extensive, rapid developmental and organizational changes.1–5 Biological and environmental stresses and insults sustained during this period might negatively impact brain development.6 Therefore, to be able to better assess the impact of a chemical exposure on developing brain, it is important to gather information about the biological transformations occurring during postnatal development of the animals used in toxicoproteomic studies. Working toward this goal, we applied proteomics to investigate the protein changes occurring during the early postnatal rat cortical development. To allow comparisons with existing literature data, we used the developmental profile of proteomic changes in the control animals in this report. This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the modified TFA-based sample preparation method7 and high-resolution MS label-free quantitation in postnatal day (PND) protein profiling using unfractionated brain cortex samples. It sets the stage for the pending treated vs control experiments investigating toxicoproteomic environmental exposure endpoints in young rats and for further hypothesis-based focused follow-up studies. Importantly, the PND protein ratios were substantiated by good linear correlation of the synaptosomal and microsomal data subgroups of this dataset with the corresponding protein ratio data obtained from the high-quality MS dataset produced from fractionated rat cortex proteome utilizing the 15N Stable Isotope Labeling in Mammals (SILAM) methodology.5 In addition, the current study focused on the protein changes in the male and female rostral cortices at the PND 2, 8, 15, and 22 and on the resulting protein profile comparison with the PND protein profiles available from the mouse cortex synaptosome study.1 The rat vs mouse comparison was facilitated by the availability of the appropriate mouse proteomic dataset published in a Microsoft Excel format, Supplementary Table 1 in ref 1, which was transformed to provide close-in-time PND reference points. For the reason of clarity and convenience of the between-study PND profile comparison, the current work adopted the exact cortex protein grouping as it was presented in ref 1, although the protein assignment as pre- or postsynaptic is arguably not always accurate. First, this is because this work does not involve fractionation, and second, this is because different fractionation-based studies classify proteins as both pre- and postsynaptic and often there is little consensus in the matter of such assignment.8 Overall, the current data and the data comparisons demonstrate noteworthy PND trendline similarities and correlations between the rat and mouse PND synaptic protein ratio change trends and between the total and fractionated rat cortices,5 despite the differences in the proteomic LC–MS techniques, in the protein extraction, labeling and fractionation approach, data processing software, and PND time points, and in the animal species and animal numbers used per PND group.

This work provides LFQ proteomic data reference for future toxicoproteomic studies, highlights the possible similarities and differences between the early PND development of the synaptic proteome in rat vs mouse cerebral cortex, and describes selected trends in the male and female rat PND proteomic profiles. It contributes to the general understanding of the protein changes occurring during the early postnatal development days and demonstrates the feasibility of comparing different proteomic datasets obtained from different laboratories for studying proteomic ratio change trends. The study also demonstrates the utility of logarithmic PND trendlines anchored to a proximal PND time point to visualizing and comparing PND data from different studies, and it provides additional quantitative PND protein ratio data, which have not yet been captured in the previous studies.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Sample Preparation

For proteomic experiments, Long Evans pup cortical brain tissues were collected throughout the postnatal period (PND 2, 8, 15, and 22); animals were perfused with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 147 mM NaCl, and 142 mM Na2HPO4) containing 10 μM sodium nitroprusside, and the tissue was dissected, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C. During the tissue dissection, the brain was sliced in half at the optic chiasm and all cortices rostral to that slice were collected. The rostral cortex samples were processed as six individual samples for each PND using a SPEED method (with some adjustments to accommodate brain tissue), which was initially demonstrated in the LC–MS analyses of bacteria, HeLa, and lung tissue proteins.7 The samples were randomized to avoid sample processing bias. Briefly, whole frozen rat brain cortex tissues, weight ranging from 30 to 398 mg, were placed in a 5-fold excess of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA 5 μL/mg of tissue) and dissolved by agitation for 10 min at 37 °C. Ten microliter aliquots of the TFA cortex solution were pH-set to ca. 8.5 (pH range between 8 and 9) by adding 100 μL of 2 M Tris base solution (pH-unadjusted)7 and then were reduced and alkylated for 10 min at 90 °C (in the dark) using an added mixture of 11 μL of a 100 mM TCEP and 400 mM 2-chloroacetic acid solution. After cooling to room temperature, the mixtures were diluted with a 5-fold amount of water to 605 μL of the total volume. The mixture was briefly probe-sonicated to ensure uniform suspension without aggregation, and a McFarland Turbidity protein assay was performed to estimate the protein concentration in the extracted samples.7 The protein samples were placed in a thermomixer and digested with trypsin (50:1 protein-to-trypsin ratio) at 37 °C for 18 h with agitation.7 The digestion was quenched by acidification with TFA (2% final concentration) and desalted on reversed-phase solid phase extraction C18 SPE 1 mL bed volume cartridges using 3 mL of the elution solvent consisting of 30% water, 70% methanol, and 0.2% TFA, optimized to facilitate elution of all peptides including the long ones. The peptide eluates were evaporated in two steps: the bulk volume of methanol was reduced under nitrogen in a TurboVap (Biotage) in 15 mL glass tubes, and then the samples were evaporated to dryness in a Centrivap Concentrator (Labconco) in 1.5 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes. The dried peptides were stored at −80 °C until the sample batch was ready for the nLC–MS analysis. Subsequently, the dried peptides were solubilized by agitation (vortex) in 200 μL of an aqueous 2% acetonitrile and 0.2% TFA solution. Using 0.2% TFA was superior to 0.1% formic acid to ensure reproducible peptide solubilization (unpublished data), and the peptide concentration was determined using a Pierce Quantitative Colorimetric Peptide Assay, PI23275. The peptide concentration was adjusted to 200 μg/μL and used for the nLC–MS label-free quantitative proteomic analysis.

Nanoflow LC–MS (MS/MS) Analysis

One microliter of a 200 ng/μL peptide solution was injected onto an Acclaim PepMap 100 Å, 2 μm, 75 μm × 2 cm nanoViper C18 loading column (Thermo Fisher) maintained at 45 °C in an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC RSLCnano system (Thermo Fisher-Dionex) operating at the loading LC flowrate of 3 μL/min of 0.1% formic acid in 98% water and 2% acetonitrile (HPLC water and acetonitrile from Thermo Fisher). The peptides were separated on an EASYSpray 50 cm PepMap RSLC C18 column (75 μm i.d., 100 Å, 2 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) using a linear gradient at the flowrate of 600 nL/min, from 0 to 2.4% B in 6 min to 20% B in 103 min, to 32% B in 123 min. (total time), and to 95% B in 125 min, followed by an isocratic flow period (10 min), returning back to 2% B in 2 min. The column temperature was maintained at 45 °C by an EASYSpray column housing heater. The Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) was operated in a data-dependent scanning mode with the precursor m/z range of 380–1500 m/z, at a full scan resolution of 120,000 FWHM, and the normalized AGC target value of 300%. The maximum injection time was set to “Auto”; the total data-dependent scanning cycle time was 3 s. The most intense ions were chosen for high-energy dissociation (HCD) at a normalized collision energy of 28%. The MSMS centroid spectra were collected using a precursor ion isolation width of 1.6 Da at a resolution of 60,000 FWHM measured at 200 m/z, with a maximum injection time set to “Auto”, the first mass set to 120 m/z, the intensity threshold of 5000, and the normalized AGC target set to 75%. The precursor ion dynamic exclusion count was set to 1, the exclusion duration to 20 s, and the mass tolerance to 10 ppm. The peptides were ionized using electrospray within an EASYSpray column built-in sprayer at a voltage of 1.8 kV and were transferred into the mass spectrometer through a heated ion transfer tube at 300 °C.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data Processing

Proteome Discoverer v.2.5 (PDv.2.5) (Thermo Scientific) was used for protein identification and LFQ quantitation. Ninety-six LC–MS .raw data files, each one representing an animal rostral cortex, were grouped in 16 LFQ groups containing 6 biological sample repeats per group. The 16 groups were constructed by combining the following sample descriptions: PND 2, 8, 15, and 22 with the male and female sample subgroups and the treated and control, non-treated subgroups. The sample files were used by the software in the two distinct processes: protein identification (in the processing step) and LFQ quantification (in the consensus step). The rat chemical treatment research LFQ findings are outside the scope of this paper, and although the whole set of the 96 sample files benefited the cortex protein identification part, the subset comprised of the 48 non-treated animal LFQ dataset was further quantitatively analyzed and discussed in this paper (Table S1). The eight groups of the LFQ dataset (six biological repeats per groups) were P2M, P8M, P15M, P22M, P2F, P8F, P15F, and P22F, and hence, there were six calculated protein ratios: P2M/P22M, P8M/P22M, P15M/P22M, P2F/P22F, P8F/P22F, and P15F/P22F, anchoring the data to the last available PND 22. All PDv.2.5 software settings for the processing and consensus steps can be found in Tables S2 and S3. Briefly, protein identification (sample processing) was carried out in 21 processing nodes in PDv.2.5 starting with a spectrum file recalibration node and a Minora Feature Detector and a Precursor Detector node, which were important for the interpretation of the chimeric MSMS spectra. The subsequent processing steps were carried out in a sequence, and the bulk of protein identification was performed in the two MSPepSearch library search nodes: the first accommodating a complete trypsin cleavage and the second performing a semi-tryptic one. In the absence of the rat library in the PDv.2.5 NIST peptide library menu, the MSPepSearch library nodes utilized human peptide libraries for matching the homologous MSMS rat data to the tryptic and semi-tryptic protein digest MSMS libraries, in conjunction with the Rattus norvegicus protein fasta database assigning the peptide sequences to rat proteins. Subsequently, four sequential SEQUEST nodes performed protein identification for the remaining unassigned .raw MSMS data, including the peptides possessing several common amino acid modifications that were absent from the peptides libraries. This task was divided into four SEQUEST nodes to minimize the search space size (Table S2). Protein LFQ consensus step consisted of 16 PDv.2.5 nodes, starting with the MSF Files node (utilizing the .msf files obtained from the preceding processing), involving the data quality threshold settings for the LFQ, a Feature Mapper node for the LC retention time chromatographic alignment of the quantifiable features in the dataset, and a Precursor Ion Quantifier node for setting the LFQ quantitation parameters including the hypothesis testing rules. Importantly, the Precursor Ion Quantifier node included the following parameters: protein abundance calculation by summed peptide MS feature intensity abundances, protein ratio calculation by using the median protein abundance of the six biological repeats, and the hypothesis test selected as the individual protein intensity-based ANOVA (Table S3) to give the p-values and the adjusted p-values assigned to protein ratios. The Peptide and Protein Filter node allowed only the high-quality peptide and protein identification results, and the protein identifications characterized by at least two peptide sequences (the protein FDR confidence was set to “high”).

Data Comparison

The protein identification and LFQ data table was exported from PDv.2.5 to Microsoft Excel (Table S1). The following abbreviated code was used in the result table to identify the PND: P2 = A, P8 = B, P15 = C, and P22 = D. Protein abundance CV% values were calculated by PD2.5 software for every protein for the six male and six female samples per group, and the results are included in Table S1 in columns IF–IM. Most CV% values were found within the 0–20% range, and the detailed CV% distribution across sample groups was as follows: (a) CV% within 0–20% for the following: females, P2: 71.9%, P8: 79.6%, P15: 80%, P22: 78%; males: P2: 72.5%, P8: 81.5%, P15: 71.9%, P22: 70.8%; (b) CV% within 20–40% for the following: females, P2: 19.2%, P8: 14.2%, P15: 14.2%, P22: 15%; males: P2: 19.4%, P8: 14.1%, P15: 18.9%, P22: 19.4%; (c) CV% within 40–60% for the following: females, P2: 6.3%, P8: 4.1%, P15: 3.9%, P22: 3.8%; males: P2: 5.4%, P8: 2.9%, P15: 5.9%, P22: 5.9%; (d) CV % within 60–100% for the following: females, P2: 2.5%, P8: 1.9%, P15: 1.6%, P22: 2.2%; males: P2: 2.2%, P8: 1.3%, P15: 2.5%, P22: 2.8%; (e) CV% above 100% for the following: females, P2: 0.20%, P8: 0.20%, P15: 0.27%, P22: 0.16%; males: P2: 0.43%, P8: 0.20%, P15: 0.82%, P22: 1.06%, where the listed percent values following the PND symbols represent the percentage of proteins quantified in a given male and female category falling within the protein abundance CV% range. The logarithmic ratios, abundance ratio (log2) (female, PX)/(female, P22) and abundance ratio (log2) (male, PX)/(male, P22), x = 2, 8, 15, and 22, and the corresponding adjusted p-values generated by PDv.2.5 were used for the data comparison with the datasets available from refs 1, 4, and 5. Consequently, the mouse cortex synaptosome-fraction data from Supplementary Table 1 in ref 1 were re-normalized from P280 to P21 by subtracting the Excel columns H from F and H from G: log2 (Pn/P280) − log2 (P21/P280) = log2(Pn/P21), where n = 9 and 15. This calculation shifted the mouse PND trendline curves presented in ref 1 by the −log2 (P21/P280) vector, thus forcing them through the zero point at P21. This curve shift did not change the curve shape, but it facilitated trendline comparison for the PND, P2, P8, P15, and P22 (rat) vs P9, P15, and P21 (mouse), by bringing the reference zero points closer. Similarly, the log2 P1/P20 and −log2P10/P20 synaptosome and mitochondrial protein ratios were calculated for the matching protein gene symbols between the compared datasets using the p1, p10, and P20 average abundance data from Supplementary Table 5 in ref 5 and from Supplementary Table 8 in ref 5. These ratios were the base for construction of the PND trendlines P1, P10, and P205 for the comparison with the corresponding protein P2, P8, P15, and P22 trends (current data), thus taking advantage of the proximity of the P20 and P22 reference points. All the matching protein ratio data are collected in Table S4.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A total of 2577 male and female rat proteins were identified with high confidence (protein high FDR confidence in PDv.2.5), and 2573 proteins were assigned at least one quantifiable PND ratio (male or female) using a proteomic label-free (LFQ) methodology (counting the proteins passing the criteria set in PDv.2.5, Table S3). Specifically, 1917 male rat proteins and 1894 female proteins produced quantifiable and statistically significant nonzero LFQ log2 Pn/P22 ratios (n = 2, 8, and 15) over the rat PND timeframe. A protein ratio was deemed statistically significant in an ANOVA LFQ protocol of the PDv.2.5 processing workflow when it possessed an adjusted p-value of 0.05 or less. A lack of systematic technical-procedural errors in the dataset was evidenced by the PCA data grouping in PDv.2.5, which showed that the only noticeable rat protein data grouping was that according to the PND (Figure S19). The PDv.2.5 protein data reports were exported to Microsoft Excel for further analysis and for comparison with the published mouse cortical synaptosome proteomic data.1 First, the mouse data (Supplementary Table 1 in ref 1) were re-normalized from P280 to P21 according to the above description. The mouse data, which were retrieved from Supplementary Table 1,1 showed 1978 identified proteins, including 696 statistically significant mouse protein PND trends over time.1 The mouse vs rat data comparison was performed according to the synaptic protein mouse data layout in ref 1 by constructing the corresponding protein ratio change trendlines. The rat PND data and closest corresponding mouse PND data points were chosen for the trendline comparison. The mouse and rat gene symbols in the combined data table were used in Microsoft Excel to match the rat and mouse PND log2 (ratio) data. The rat protein ratios, log2 P2/P22, log2 P8/P22, and log2 P15/P22, and the resulting protein trendlines were compared with the similar mouse protein ratios of log2 P9/P21 and log2 P15/P21, presented as the reconstructed trendlines, following the layout of Figures 6–8 and Table 1 in ref 1. In the current work, out of the total of 2573 quantifiable rat proteins possessing a log2 Pn/P22 PND ratio, 1235 proteins were also reported in the mouse study.1 As a subgroup of that total, 508 quantifiable rat proteins were matched by a gene symbol to the 696 statistically significantly changing mouse proteins over time across the PND experiments (Bayesian Estimation of Temporal Regulation, BETR ≤ 0.001) in ref 1. Among the 508 proteins, 453 male rat proteins and 456 female rat proteins possessed at least one adjusted p-value of 0.05 or lower among the three studied PND ratios (Table S4). To compare the rat dataset to the published mouse data1 and to highlight the biologically relevant information, the rat data were split into the same functional groups: presynaptic proteins (Figures 1–7), post-synaptic proteins (Figures S1–S7), and adhesion proteins (Figures S8–S10). In addition, the proteins demonstrating the most prominent changes in the mouse brain development, which were originally shown in Table 1 in ref 1 as referenced to P280, were displayed as the shorter PND trendlines referenced to P21 and compared in Figures S11–S13 with the rat counterparts. The upper right quadrants of these figures show the trendlines constructed for the quantifiable synaptic cortex rat proteins calculated from Supplementary Table 5 in ref 5, which were also shown in the mouse1 and current rat data presented in Figures 1–7 and Figures S1–S13. Finally, the mouse protein data from ref 1, for which both the LC/MS and immunoassay quantitative data were available in Supplementary Figure 1 in ref 1, were compared with the current LFQ rat quantitative data. Both the rat male and female PND trendlines were constructed independently using the corresponding data. Adopting such classification of the synaptosome proteins as the presynaptic and postsynaptic categories based on ref 1 was useful for the rat vs mouse protein profile comparison purpose, but it was somewhat arbitrary considering that, according to a recent literature review, many synaptosomal proteins were categorized as both pre- and postsynaptic in numerous publications.8 The reliability of such protein classification increases with the number of the reference papers confirming the assignment. Hence, in this work, we also cross-referenced each protein with the number of publications listed in ref 8, identifying each protein as presynaptic, postsynaptic, or none (Table S4). Out of the total of the 2577 rat cortex proteins, which were identified in the current work, 618 were classified in ref 8 as neither presynaptic nor postsynaptic, whereas 1648 proteins were described in ref 8 as postsynaptic and 821 proteins as presynaptic by more than one publication source. Using the same criteria, 848 and 21 proteins were categorized as exclusively postsynaptic or presynaptic, respectively, while 800 proteins were categorized as both. After applying a stricter “greater than four publications” qualifying criteria, 882 and 11 proteins were categorized as exclusively postsynaptic or presynaptic, respectively, while 233 proteins were categorized as both, and 882 were classified as neither.

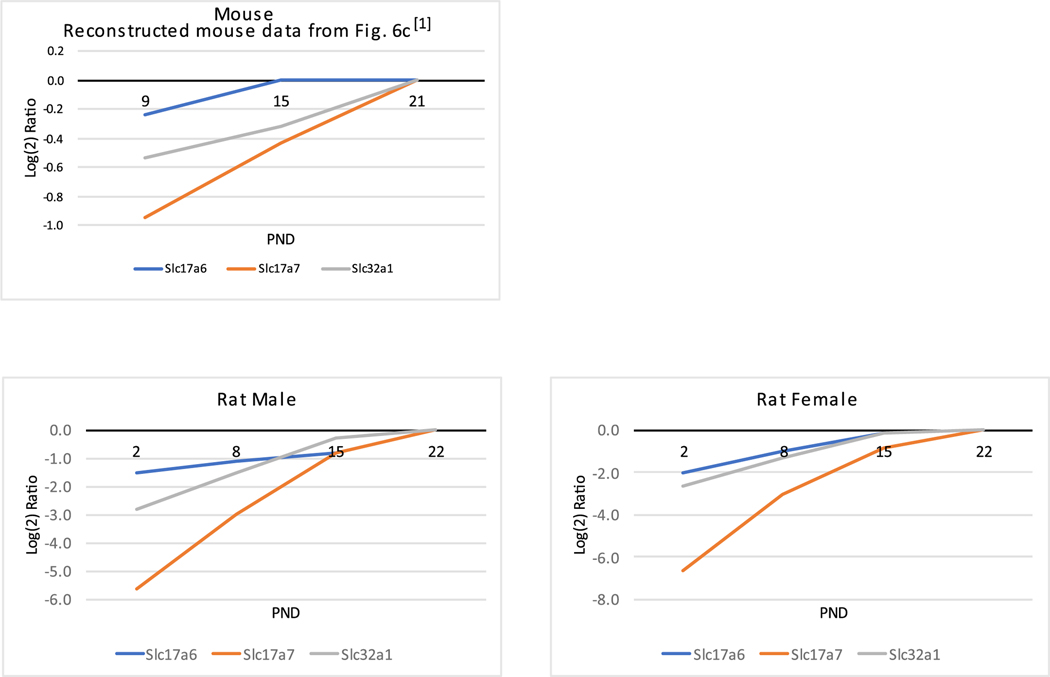

Figure 6.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6f in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The top right quadrant shows the rat protein PND trendline constructed from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5 for the protein matching the gene symbol of the male and female presynaptic cortical rat protein quantified in the current work (these proteins are presented in the bottom plots).

Figure 8.

(a, b) Linear correlation plots comparing the male (top quadrant) and female (bottom quadrant) rat rostral cortex logarithmic protein abundance PND ratios P8/P22 (a) and P15/P22 (b) passing the adjusted p-value 0.05 threshold vs the corresponding mouse cortex synaptosome P9/ 21 and P15/P21 data,1 respectively. The data include the discussed above presynaptic, postsynaptic, adhesion, and highly expressed proteins quantified both in the mouse1 and rat studies (current work).

Figure 1.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6a in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The top right quadrant shows the rat protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5 for the proteins matching the gene symbols of the male and female presynaptic cortical rat proteins quantified in the current work (presented in the bottom plots).

Figure 7.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6g in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The top right quadrant shows the rat protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5 for the proteins matching the gene symbols of the male and female presynaptic cortical rat proteins quantified in the current work (presented in the bottom plots).

Presynaptic Proteins

Out of the 11 quantifiable synaptic vesicle mice proteins1 involved in the neurotransmitter release cycle, there were seven corresponding quantifiable rat male and female proteins (Figure 1). In agreement with the mouse study data, five proteins, SC2A, SV2B, SYN1, SYN2, and SYP synaptic vesicle proteins, showed increasing levels with similar slight differences in the order of the extent of protein regulation. SCAMP1 was, as it was observed in the mouse data,1 also minimally increasing. The exception was SYN3, which showed a small decreasing trend in mice and flat-to-minimally increasing trends both in the male and female rats. Both SYP and SV2A demonstrated analogous trendlines in the male and female rat cortices and in the cortex rat synaptosomes, where the trendlines consisted of three protein ratios, log2 P1/P20, log2 P10/P20, and log2 P20/P20, with an abbreviated symbol (P10/P20) and constructed from the rat synaptosome data in ref 5. Residing on the membrane of small synaptic vesicles was Synapsin, SYN1, which was shown to bind spectrin SPTBN2, which was deemed essential for synaptic transmission.9 In the current work, both SPTBN2 and SPTBN1 were quantified. SPTBN2 and SPTBN1 exhibited similarly rising PND ratio profiles: SPTBN2: −1.65 (P2/P22), −1.27 (P8/P22), and −0.53 (P15/P22) in male rats, −1.65 (P2/P22), −1.25 (P8/P22), and −0.54 (P15/P22) in female rats (current work), and −1.89 (P1/P20) and −0.92 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes;5 SPTBN1: −1.32 (P2/P22), −0.73 (P8/P22), and −0.26 (P15/P22) in male rats, −1.32 (P2/P22), −0.75 (P8/P22), and −0.27 (P15/P22) in female rats (current work), and −1.22 (P1/P20) and −0.37 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 In contrast, in the mouse synaptosomes, only SPTB1 was quantified, and it produced a minimally rising PND profile from P9 through P15 to P21. CAMSAP1 (calmodulin-regulated, spectrin-associated protein 1)10 was quantified in the current work (Table S4), and it produced a mildly decreasing trend between P2 and P22 while showing a flat profile in mouse synaptosomal fraction,1 but it was not quantified in the rat synaptosomal fraction.5 It is worth noting that synaptophysin (SYP) was also quantified on the western blot,5 demonstrating a visible SYP band only in the synaptosome isolate blots and not in the unfractionated brain protein extracts of P1, P10, P20, and P45 (Supplementary Figure 5 in ref 5). However, in the current rat cortex study, SYP was identified based on six unique peptides, and it was quantified without difficulty by LFQ using the unfractionated cortex extract, thus demonstrating good sensitivity for that protein in the current LFQ study. Interestingly, in parallel to the rostral cortex rat protein PND profiles, SYN1, SYN2, SYP, and SNAP25 showed also increasing levels from P1 through P45 in the rat cerebellum.3

All functionally similar proton-pump ATPase subunits of a vesicle type demonstrated protein level increases both in mice1 and male and female rats throughout the PND 2–22 (Figure 2). However, ATP6V1C1 appeared out of sequence as it displayed a much flatter curve in mice in comparison with the male–female rat study. The log2 (ratio) values showed the larger magnitude changes in rat vs the changes observed in mouse. Interestingly, this general ratio magnitude difference was true for most of the rat vs mouse proteins compared in this study. However, the protein ratio trendlines, which were reconstructed based on the supplemental rat synaptosome data in ref 5, showed the analogous sharply increasing protein ratios from P1 to P20 for the two proteins ATP6V0A1 and ATP6V1B2, matching both the current rat study and the mouse1 datasets. Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPases 1–4 and ATP2A2 also showed increasing trends in the rat rostral cortex (current work), in agreement with the rat cerebellum synaptosome P1–P45 data,3 while in the mouse cortex synaptosome, only ATP2B2 was identified and showed an increasing ratio trend between P9 and P21.

Figure 2.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6b in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The top right quadrant shows the rat protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5 for the proteins matching the gene symbols of the male and female presynaptic cortical rat proteins quantified in the current work (presented in the bottom plots).

Three glutamate and GABA vesicular transporters (Figure 3), which were assigned to the presynaptic section based on ref 1, showed increasing PND protein expression trends comparing the rat and mouse data, although the magnitude of the protein ratio increases in mice was, again, noticeably smaller. Related by a synaptic vesicle complex, proteins Bassoon (BSN), piccolo (PCLO), and ERC2 showed similarly increasing trends across the studied PND timeline (ref 1 and the reference therein). LIN7A and UNC13A also increased. The overall PND trendline picture was similar between the mice and rat studies and was characterized by BSN showing the steepest increase, with CASK showing the flattest and barely changing expression pattern from P8 to P22 (rat) and P9 to P21 (mouse). The independently obtained male and female rat trendlines were almost identical (Figure 4 and Table S4).

Figure 3.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6c in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The male and female presynaptic cortical rat proteins quantified in the current work are presented in the bottom plots.

Figure 4.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6d in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The male and female presynaptic cortical rat proteins quantified in the current work are presented in the bottom plots.

Despite the varying profile line directions shown in Figure 5, again, there was an agreement between the rat and mouse protein change patterns for P9–21 (mouse)1 and P8–P22 (rat). The synaxins STX7, STX12, and SNAP29 were decreasing, and STX6 and STX8 were close to being flat, whereas the syntaxins STX1A and STX1B were increasing sharply. One difference was found between the mouse and rat SNAP47 lines: it was somewhat decreasing in mice, while it was sharply increasing in the male and female rat experiments. The syntaxin STX1A and STX1B trendlines demonstrated an almost identical shape and magnitude of the PND changes for the proteins quantified in the current rat study and in the rat synaptosome study (ref 5 and Supplementary Table 5 therein). Syntaxin, synaptotagmin (SYT1), complexin I/II, and syntaxin-binding proteins are functionally related, as they participate via membrane fusion in the presynaptic vesicle Ca2+-controlled neurotransmitter release (ref 11 and references therein). Accordingly, SYT1 exhibited rising PND ratio profiles analogous to the syntaxins STX1A and STX1B: −0.91 (P9/P21) and −0.39 (P15/P21) in mouse synaptosomes,1 −3.16 (P2/P22), −1.93 (P8/P22), and −0.59 (P15/P22) in male rats, −3.25 (P2/P22), −1.97 (P8/P22), and −0.62 (P15/P22) in female rats (current work), and −2.22 (P1/ P20) and −1.08 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 In addition, the synaptotagmins SYT2, SYT5, SYT7, SYT11, SYT12, and SYT17 were quantified in the current work, all demonstrating steeply rising trendlines between P2 and P22, except for SYT6, which showed a flat trendline. In contrast, in the mouse synaptosome fraction, only SYT2 and SYT7 were quantified besides SYT1, and they presented a close to a flat trend from P9 and P15 to P21 with a significant change later past the P21 zero reference point. The rat synaptosome fraction proteomic study did not list these synaptotagmins as quantified in Supplementary Table 5 in ref 5.

Figure 5.

The top left quadrant shows the presynaptic cortical mouse protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 1 data in ref 1 for the proteins from Figure 6e in ref 1, which match the gene symbols of the rat protein quantified in the current work. The top right quadrant shows the rat protein PND trendlines constructed from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5 for the proteins matching the gene symbols of the male and female presynaptic cortical rat proteins quantified in the current work (presented in the bottom plots).

In the current work, the functionally related complexins CPLX1 and CPLX2 demonstrated almost identical, steeply rising PND profiles from P2 to P22: CPLX1: −2.58 (P2/P22), −1.32 (P8/P22), and −0.32 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.48 (P2/P22), −1.32 (P8/P22), and −0.33 (P15/P22) in female rats; CPLX2: −2.36 (P2/P22), −1.17 (P8/P22), and −0.22 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.33 (P2/P22), −1.06 (P8/P22), and −0.14 (P15/P22) in female rats (Table S4). The mouse synaptosome study showed a similar CPLX1 rising trend: −1.04 (P9/P21) and −0.45 (P15/P21). In contrast, CPLX1 and CPLX2 were not reported among the quantified cortex synaptosome proteins in ref 5. Functionally related to STX1A and STX1B, syntaxin-binding proteins STXBP1 and STXBP5 were reported and quantified in all three studies, demonstrating steeply rising PND trendlines in this rat study and in the synaptosome fraction rat work.5 The mouse study reported these proteins as moderately increasing in abundance: STXBP1: −1.89 (P2/P22), −1.15 (P8/P22), and −0.36 (P15/P22) in male rats and −1.89 (P2/P22), −1.07 (P8/P22), and −0.34 (P15/P22) in female rats; −0.56 (P9/P21) and −0.24 (P15/P21) in mouse synaptosomes1 and −1.92 (P1/P20) and −1.00 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes (calculated from the data in ref 5); STXBP5: −2.11 (P2/P22), −0.86 (P8/P22), and −0.14 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.21 (P2/P22), −0.83 (P8/ P22), and −0.07 (P15/P22) in female rats; −0.55 (P9/P21) and −0.28 (P15/P21) in mouse synaptosomes1 and −2.93 (P1/P20) and −1.44 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5

In addition to the aforementioned key regulatory components of the membrane fusion SNARE complex, the Vesicle-Fusing ATPase (NSF), Alpha-synuclein (SNCA), and Vesicle-associated membrane proteins (VAMP1, VAMP2, VAMP3, VAMP4, VAMP7, and VAMP8) were also part of the complex (ref 12 and the references therein), with VAMP2 being the most prominent. Accordingly, these proteins demonstrated similar rising PND expression profiles. The NSF PND profile was as follows: −2.79 (P2/P22), −1.72 (P8/P22), and −0.49 (P15/ P22) in male rats and −2.89 (P2/P22), −1.78 (P8/P22), and −0.54 (P15/P22) in female rats; −0.61 (P9/P21) and −0.22 (P15/P21) in mouse synaptosomes1 and −2.40 (P1/P20) and −1.33 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 The PND profile for SNCA was as follows: −2.24 (P2/P22), −1.17 (P8/P22), and −0.20 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.65 (P2/P22), −1.21 (P8/P22), and −0.37 (P15/P22) in female rats; −0.82 (P9/P21) and −0.25 (P15/P21) in mouse synaptosomes1 but not quantified in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 The PND profile of VAMP2 was as follows: −2.06 (P2/P22), −1.17 (P8/P22), and −0.28 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.15 (P2/P22), −1.14 (P8/ P22), and −0.37 (P15/P22) in female rats; −0.47 (P9/P21) and −0.21 (P15/P21) in mouse synaptosomes1 and −2.68 (P1/ P20) and −1.14 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 VAMP1, VAMP3, and VAMP7 were also quantified showing analogous steep-rising P2–P22 PND profiles in the current work; however, they were not quantified in refs 1 and 5 and Table S4.

As demonstrated in Figure 6, there were similarly increasing trendlines for mouse and rat voltage-dependent presynaptic and postsynaptic calcium channel subunits CACNA2D1, CAC-NA2D3, CACNB3, CACNB4, and CACNA1E (with some slope difference), while CACNA2D2 was almost flat. However, CACNB1 exhibited a different direction in the mouse and rat experiments. CACNA2D1 exhibited the same shape and magnitude of the PND protein changes in the current rat data and in the synaptosome rat protein data reported in Supplementary Table 5 in ref 5. CACNG8 was uniquely quantified in the current work, presenting a steeply rising PND line from P2 to P22.

A functional subgroup of calcium-managing proteins is the plasma membrane calcium ATPases (PMCAs), which extrude calcium ions from cytosol to the extracellular space. These key regulators of calcium signaling are formed from four PMCA subunits 1–4, neuroplastin, and basigin.13 The four PMCA subunits ATP2B1–ATP2B4, neuroplastin (NPTN), and basigin (BSG) were quantified in the current work, and their PND profiles were compared with the ones constructed based on the data presented in refs 1 and 5. All four subunit PND profiles were almost identical (current work), and the two subunits 1 and 3 were quantified in ref 5, all showing similarly rising protein PND profiles. Only subunit 2 was quantified in mouse synaptosomes,1 displaying a moderately rising trend. NPTN was quantified in rats (current work) with a sharply rising PND P2–P22 trend, whereas mouse synaptosome data1 indicated a moderate increase between P9 and P21. Concurrently, basigin displayed a steep PND protein increase both in the rats (current work) and in the rat synaptosome data,5 whereas it could not be quantified with statistical significance in the mouse synaptosome data1 (Table S4).

Proteins linked to clathrin-mediated endocytosis (ref 1 and the references therein) all showed increasing trends for the mouse and rat PND time points P9, (P8), P15, and (P15), relative to P21 (P22) (Figure 7). The three clathrins, CLTA, CLTB, and CLTC, exhibited close expression patterns in both species. Among the nine compared trendlines, DNM1 showed a steep increase both in the male and female rats and in the mouse experiments. A characteristic pattern for all trendlines was a large increase toward the P15 point and then a small increase toward P21 (P22) reference points. Overall, these presynaptic proteins demonstrated remarkable similarities in the early postnatal development between the mouse and rat species, whereas the observed changes between the male and female rats were mostly identical. Three proteins, DNM1, CLTC, and SH3GL2, which were quantified in rat synaptosome,5 were also quantified in the present rat cortex male/female study and in the mouse cortex synaptosome study.1 In the two rat studies, DNM1 trendlines were almost identical, while CLTC and SH3GL2 were similar in the direction of the PND protein changes, although the magnitude of the protein ratios at the first PND data point was larger in ref 5 (Figure 7). The related dynamins DNM1L, DNM2, and DNM3 were uniquely quantified in the current work, and their PND profiles were similarly rising from P2 to P22 (Table S4).

Postsynaptic Proteins

GRIN1 and GRIN2B, the NMDA receptor proteins, presented a similar early-PND trendline in rats and mice:1 both GRIN1 and GRIN2B increased since the early age, and the GRIN1 line was steeper than that of GRIN2B (Figure S1). At the development time points 8–22, glutamate receptor proteins GRIK3, GRM2, GRM3, GRM5, and GRM7 moved around the log2 (ratio) zero axis line, although in rats, there was a distinct increase between P2 and P8 for all proteins except for GRIK3. At P8, the relative positions of the mouse and rat log2 (ratio) values were similar, with GRM5 and GRM7 positioned above the zero line, GRM3 positioned close to the zero line, and GRM2 and GRIK3 below (Figure S3). Three AMPA receptor proteins, GRIA1, GRIA2, and GRIA3, showed similar increasing trends in rats and mice. The P8 to P15 protein abundance increases in rats were larger than the corresponding protein increases in mice (Figure S2). The NMDAR, KA, and AMPA receptors are part of a multiprotein complex at the glutamatergic synapse.14 Other proteins from the glutamatergic synapse pathway, which were quantified in the current study, were the ERK mitogen-activated protein kinases MAPK1 and MAPK3, which produced statistically significant PND ratios but were not quantifiable in mouse synaptosomes.1 In contrast, MAPK1 was quantified in the rat synaptosome study,5 and the PND profiles of MAPK1 were as follows: −1.34 (P2/P22), −0.92 (P8/P22), and −0.28 (P15/ P22) in male rats and −1.27 (P2/P22), −0.89 (P8/P22), and −0.13 (P15/P22) in female rat; −1.42 (P1/P20) and −1.06 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 The protein kinase C protein group PRKCA, PRKCB, and PRKCG from the glutamatergic synapse pathway displayed similar rising trends from P2 to P22, ranging between the P2/P22 ratio of −2.75 and the P15/P22 ratio of −0.2 (current work). In the mouse synaptosome study, only PRKCG showed a shallow rising trend from the P9/P22 of −0.33 to −0.11 for P15/P22 (Table S4). The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate endoplasmic reticulum receptor protein ITPR1 displayed a rising PND protein ratio trend: −2.73 (P2/P22), −2.06 (P8/P22), and −0.78 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.53 (P2/P22), −1.91 (P8/P22), and −0.85 (P15/P22) in female rats, in contrast to the almost flat P9–P22 profile in mouse synaptosomes.1 Among the glutamatergic synapse pathway proteins, glutamine synthetase (GLUL) exhibited the largest P2/P22 protein ratio increase of −4.02 (male rat) and −3.95 (female rat), which corresponded to the analogous increase of −4.14 for P1/P20 in rat synaptosomes;5 the P2/P22 protein ratios were −1.98 (male rat), −1.87 (female rat), −1.34 (P1/P20, rat synaptosomes5), and −0.83 (P9/P21, mouse synaptosomes1). The excitatory amino acid transporter proteins SLC1A2 and SLC1A3 also exhibited large PND protein ratio increases in the current work and in the synaptosome fraction studies.1,5 Five guanine nucleotide binding proteins GNAI1–GNAI3, GNAO1, and GNAQ14 showed a moderately increasing PND pattern (current work), which was paralleled by a similar trend described in the rat synaptosomes for GNAI1 and GNAO1.5 GNAO1 showed only a small increase between P9 and P21 in the mouse synaptosomes,1 but no change was observed for the other four GNAI and GNAQ proteins (Table S4). Additional five guanine nucleotide binding proteins GNB1, GNB2, GNB4, GNB5, and GNB7 of the glutamatergic synapse pathway showed a modestly rising P2–P22 protein abundance profile, except for GNG7, which displayed a larger protein ratio increase from −2.6 for P2/P22. In contrast, the corresponding mouse synaptosome profiles1 ranged from small to flat. The rat synaptosome data5 showed only one quantitative profile for this group of proteins for the GNB1 protein, for which the P1/P20 and P10/P20 ratios exhibited a modest increase. Three proteins of the phosphatase PP2B group, PPP3CA, PPP3CB, and PPP3R1,14 were quantified in the current work, and all three proteins exhibited rising PND profiles. The mouse synaptosome data1 also showed proportional increases in the PND protein ratios for PPP3CA and PPP3R1, while the PPP3CB trend was flat. The rat synaptosome data5 showed one quantitative P1 to P20 trend for PPP3CB, which was comparable to the one observed in the current work data. Neuronal pentraxins NPTX1 and NPTX2 are the proteins involved in the AMPA-mediated excitatory synapse assembly.15 NPTX1–NPTX2 and the receptor NPTXR were quantified in the rat cortex (current work, Table S4), showing steep rising P2–P22 PND profiles, whereas in mouse synaptosomes,1 NPTX1 displayed only a moderate increase from P9 to P21, and these proteins were not quantified in rat synaptosomes.5 Neurogranin (NRGN) is a small postsynaptic protein that binds to calmodulin.16 Both in the current work and in the rat synaptosomal data,5 NRGN exhibited a sharp increase in the PND profile, and it was not reported in mice.1

In the current rat study, the following calcium sensor calmodulin proteins and their associates were identified: CALM3, CALML3, CAMK1, CAMK2A, CAMK2B, CAMK2D, CAMK2G, CAMK2N1, CAMK4, CAMKK2, CAMKV, CAMSAP1, CAMSAP2, PDE1B, and GRK2 (Table S4). The calmodulin CALM3 and CALML3 displayed moderately increasing PND profiles, whereas the five type II kinases and CAMK4 demonstrated steeper PND profiles (ca. −2.0 for P2/P22). CAMK2A showed a similarly steep PND rise in mouse1 and rat synaptosomes5 (Figure S11). CAMK2D exhibited an analogous steep PND rise in the rat synaptosomes,5 −3.44 P1/P20 and −2.00 P10/P20, but only a small increase was noticeable in the mouse data.1 CAMSAP1 was unique in this group of proteins in that it displayed a modestly declining PND profile in the current rat study. The following neuronal calcium sensor (NCS) proteins17 were identified in the current rat study: VSNL1, NCS1, HPCAL1, HPCAL4, HPCA, NCALD, and KCNIP4. VSNL1 showed an analogous PND profile in the current rat study and in the rat synaptosome work: −2.14 (P2/ P22), −1.05 (P8/P22), and −0.1 (P15/P22) in male rats and −2.56 (P2/P22), −1.1 (P8/P22), and −0.07 (P15/P22) in female rats (current work); −2.78 (P1/P20) and −1.38 (P10/ P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 The NCS1 trend was close to flat across the studied PND points. The three hippocalcins showed strongly increasing PND trendlines (current work) while demonstrating only a moderate increase in the mouse data.1 NCALD and KCNIP4 showed strongly increasing PND trends in the current work, but they were not quantified in mice1 and rats5 (Table S4).

Postsynaptic scaffolding proteins DLG1, DLG2, DLG3, DLG4, DLGAP1, DLGAP2, DLGAP3, and DLGAP4 presented almost identical profiles for the male and female rat early PNDs, in which the proteins were sharply increasing except for DLGAP4, presenting a mildly decreasing and then a flat trendline (Figure S4). In the corresponding mouse profiles, the least changing proteins were DLG3 and DLGAP4, and this finding matched the rat cortex profiles. The trend and magnitude of the DLG3 and DLG4 protein expression changes were analogous both in the current rat study and the preceding synaptosome rat study (calculated from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5). SH3 domain and ankyrin repeat proteins (SHANKS) showed increasing trends both in rats and mice (Figure S5); the exception, however, was HOMER1, displaying a flatter trendline in rats with respect to the Shank1–Shank3 protein PND trendlines.

A variable expression was observed in the mouse vs rat PND profiles for the inhibitory metabotropic GABAB receptors and ionotropic GABAA receptors (Figures S6 and S7). In the male and female rats, all trends were either increasing or flat. In mice, most of the trends were also increasing or flat, except for GABRA3, which displayed a more sharply decreasing trend from P9 to P21, indicating that the subunit composition becomes an adult isoform (ref 1 and references therein). GABRB1 PND expression differed between the rats and the mice: it was steeply increasing in rats while being flat in mice from P9 to P21. GABBR1 and GABBR2 showed similarly shaped trendlines for the rats and mice.

Adhesion Molecules

Adhesion molecules are involved in synaptogenesis of the presynaptic and postsynaptic elements.1 In this category, ephrin receptors (Figure S8), cadherins (Figure S9), and neuroligins and neurexins (Figure S10) were found. Different isoforms from the ephrin receptor family of proteins were quantified in the mouse and rat studies (Figure S8), of which both species exhibited modest expression changes near the log2 (ratio) zero axis. NCAM1 expression peaked at P8 (rat) and P9 (mouse), and then its abundance decreased toward the corresponding P22 and P21 reference points. In the rat synaptosome study,5 NCAM1 expression also initially increased from P1 to P10, and then it leveled off between P10 and P20 (Figure S8). Both male and female rat proteomic experiments showed a great degree of similarity within the CADM1–CADM4 and CNTNAP1 groups of adhesion proteins. CADM2 showed also significant changes from P1 through P10 to P20 in the rat synaptosome study (calculated from the Supplementary Table 5 data in ref 5), replicating the trends evident in the current rat and mouse synaptosome1 studies (Figure S9). Figure S10 presents neuroligins, NLGN 1–3, and neurexins, NRXN 1–3, showing a similar abundance increase toward P15 and then stable-to-flat trends. In the adhesion protein category, the overall early PND trendlines in mouse and rat cortices were complex, displaying both rising and falling protein abundance ratios. CNTN1 exhibited identically increasing trendline shapes in the male and female cortex P2–P8–P15–P22 profiles and in the rat synaptosome reconstructed P1–P10–P20 trendlines;5 however, the trends were found opposite for CDH2 in this comparison. Mouse data, in contrast, exhibited a flat CNTN1 trendline. Neuronal cell adhesion protein NRCAM displayed a flat abundance ratio between P9 and P21 in mouse cortex synaptosome, whereas it displayed an increase in abundance between P2 and P15 followed by a flat abundance ratio from P15 to P22 (Table S4).

Adhesion ADGRL and ADGRB receptors in the nervous systems induce synaptogenesis and axonal growth.18 In the current work, ADGRL1, ADGRL3, and ADGRB1 proteins were identified based on 25, 13, and 8 unique peptides, respectively, and displayed a moderate (ADGRL3 and ADGB1) and low (ADGRL1) P2–P22 rising PND profiles. In contrast, ADGRL2 exhibited a moderately decreasing profile, while ADGRG1 was unchanging. These proteins were not listed as quantifiable either in the mouse or rat synaptosomes.1,5 Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 7, LRRC7, was classified as a postsynaptic protein that was confidently identified based on 25 unique peptides and displayed a strongly upward PND profile line both in the current work and in the rat synaptosome:5 −3.35 (P2/P22), −1.98 (P8/P22), and −0.46 (P15/P22) in male rats and −3.74 (P2/P22), −2.08 (P8/P22), and −0.50 (P15/P22) in female rats; −4.04 (P1/P20) and −1.32 (P10/P20) in rat cortex synaptosomes.5 This protein was associated with genomic neuron projection fetal development and neuron differentiation networks.19

Highly Expressed Mouse vs Rat Proteins

The mouse proteomic study1 presented a table of proteins possessing high expression differences at P9 and P15 with respect to the adult mouse proteome (Table 1 in ref 1). Figures S11–S13 present rat vs mouse trendlines for these mouse proteins listed in Table 1 in ref 1. In our study, the rat male and female trendlines were almost identical. The rat vs mouse early-PND trendlines were similar, although again in general, the magnitude of the rat protein ratio abundance changes appeared higher, both in the current study and in the synaptosome rat cortex.5 This general difference in the magnitude of the rat vs mouse PND protein ratios could be in part attributed to the analytical technique used in ref 1, as evidenced by the disparity between the immunochemistry mouse PND data trendlines and the corresponding LC–MS based trendlines presented in the Supplementary Figure 1 in ref 1. The mouse immunoblottingderived PND protein changes were largely higher than the mouse LCMS-derived expression data, thus being closer to the LC/MS rat proteome data. The rat vs mouse protein expression differences might be partly attributed to biological differences during the rat vs mouse PND development but also to the differences in the sample preparation techniques used in these two studies: the mouse brain cortex study used a cortex synaptosome, while the present rat study used the whole unfractionated rat cortex tissue. The non-synaptosome proteins were, in general, either absent or underrepresented in the mouse study relative to the rat study. Such underrepresentation is evidenced by the difference in the total number of proteins identified and quantified in the rat and mouse studies, with this current rat study showing significantly more quantified proteins.

Global Comparison of the Presynaptic, Postsynaptic, Adhesion, and Highly Expressed Protein Groups between the Three studies: Rat Rostral Cortex vs Mouse Cortex Synaptosome1 and Rat Rostral Cortex vs Rat Cortex Synaptosome5

The developmental protein relationships, which were visualized above as the PND protein ratio trendlines, were also tested using Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) and the linear correlation plots. Consequently, the logarithmic rat protein ratios described in the current study, possessing an adjusted p-value of 0.05 or less, were compared as a group with the corresponding synaptosomal fraction mouse protein ratios1 spanning the rat–mouse-shared presynaptic, postsynaptic, adhesion, and highly expressed proteins quantified both in the mouse1 and rat studies displayed in Figures 1–7 and Figures S1–S13. The Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) values for such rat log2 (P8/P22) vs mouse log2 (P9/P21) comparison were 0.84 (male rat) and 0.85 (female rat). The corresponding linear regression plot parameters were as follows: y = 0.395x + 0.185, R2 = 0.711, for the male rat rostral cortex vs mouse cortex synaptosome data correlation and y = 0.400x + 0.175, R2 = 0.722, for the female rat rostral cortex vs mouse cortex synaptosomes (Figure 8). The rat log2 (P15/P22) vs mouse log2 (P15/P21) comparison yielded the PCC values of 0.84 (male rat vs mouse) and 0.85 (female rat vs mouse) for this group of proteins. The corresponding linear plot parameters were as follows: (a) y = 0.468x + 0.012, R2 = 0.712 (male rat vs mouse), and (b) y = 0.481x + 0.019, R2 = 0.721 (female rat vs mouse) (Figure 9). The slopes of the linear regression lines were within the 0.4–0.5 range, confirming that in these two studies, on average, the synaptic mouse proteins demonstrated smaller PND changes with respect to the corresponding rat proteins. One of the possible explanations for this difference could be a ratio compression effect, which generally gives rise to protein ratio flattening in isobaric mass tagging experiments,20 depending on the degree to which it was corrected by the proteomic software used in ref 1.

Figure 9.

(a, b) Linear correlation plots comparing the male (top quadrant) and female (bottom quadrant) rat rostral cortex logarithmic protein abundance PND ratios P2/P22, adjusted p-value 0.05 threshold, vs the corresponding rat cortex synaptosome data.5 The data include the discussed above presynaptic, postsynaptic, adhesion, and highly expressed proteins quantified both in the rat5 and current rat studies. (a) Current rat data possessing the adjusted p-value of 0.05 or lower; (b) current rat data possessing the adjusted p-value of 0.05 or lower and the P1/P20 rat synaptosome logarithmic ratios only when both the P1 and P20 abundances possess the p-value of 0.05 or less (as described in ref 5).

A similar comparative analysis was performed for the rat log2 (P2/P22) current work data presented in Figures 1–7 and Figures S1–S13 and the synaptosomal fraction rat log2 (P1/P20) data calculated from the P1 average and P20 average columns in Supplementary Table 5 in ref 5. There were 85 proteins in common between such P1/P20 data from ref 5 and the current work P2/P22 data. The PCC was 0.82 for this comparison of the male rat cortex vs synaptosomal rat cortex data,5 and the linear plot parameters were as follows: y = 0.757x − 0.523, R2 = 0.670. In the corresponding comparison of the analogous female rat cortex data vs synaptosomal fraction of the rat cortex data from ref 5, the PCC was 0.82, and the linear parameters were as follows: y = 0.735x − 0.562, R2 = 0.678 (Figure 9a). This 85-protein dataset was then reduced to 21 by restricting the p-values to 0.05 or lower in both the current data and rat data from ref 5. This restriction resulted in an improvement of the PCC values for the P2/P22 vs P1/P205 comparison to 0.90 (male) and 0.90 (female), which corresponded to the following linear equation parameters: y = 0.896x − 0.692, R2 = 0.809 (male), and y = 0.858x − 0.764, R2 = 0.796 (female) (Figure 9b). A similar data analysis was performed for an analogous 22-protein data subset of the 85 proteins, meeting the requirements set above, whereby the log2 [P8/P22] dataset was correlated with the log2 [P10/P20] data from ref 5. This comparison showed the PCC values of 0.90 for the rat male data and 0.89 for the rat female data and the corresponding linear parameters of y = 0.797x − 0.365, R2 = 0.819 (male rat data), and y = 0.766x − 0.401, R2 = 0.799 (rat female data).

Biological Processes and PND Protein Changes in the Rat Cortex

Biological processes are frequently associated with networks of multiple proteins, and therefore, it is anticipated that such proteins are co-regulated. We analyzed a group of 83 28S, 39S, 40S, and 60S ribosomal proteins, which were quantified in this rat cortex study, out of which 49 proteins were in common with the mouse dataset.1 These ribosomal proteins were isolated using a “*ribosomal protein*” keyword filter in the protein description (protein name) column of the PDv.2.5 data report. The majority of the 49 ribosomal proteins exhibited decreasing ratio trends across the respective PND time points: P2–P22 and P9–P21 (Figure S14). However, the P8/P22 rat ribosomal proteins possessing the protein ratio adj. p-value of 0.05 or less1 did not correlate well with the P9/P21 mouse ribosomal proteins possessing the parameter BETR below 0.001, as it was evidenced by the poor PCC values of 0.39 (male rat) and −0.04 (female rat). Notably, none of these ribosomal protein PND changes were statistically significant in the cortex synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions described in the previous rat cortex study.5 In general, the magnitudes of the statistically significant mouse ribosomal protein PND changes were low,1 which could be explained by a merely residual presence of ribosomal proteins in the synaptosomal isolates. Therefore, this particular mouse synaptosome vs rat cortex data discrepancy could be attributed to the effects of the sucrose gradient fractionation in refs 1 and 5 and the use of whole tissue in the present study.

Twenty-seven proteasome proteins were quantified in the rat rostral cortex, presenting a very similar PND protein change profile between the male and female rat groups (Figure S15). The proteasome proteins were grouped using a keyword filter (“*Proteasome*”) in the description column of the report. The average PND protein ratio trend was somewhat decreasing. Seventeen corresponding proteasome proteins were also found in mice1 and were characterized by flat P9–P21 protein ratio profiles, which were not deemed statistically significant in ref 1, indicating that the proteasome proteins were not well represented in the mouse synaptosome fractions. In concordance with the sporadic, apparently residual, appearance and the low-level abundance of the proteasome proteins within the mouse synaptosome isolate,1 there were no proteasome proteins reported as quantifiable in the rat synaptosome cortex study.5

Two protein groups representing opposite trends in the early rat PND development were mRNA splicing proteins and mitochondrial proteins. The mRNA proteins showed a mostly decreasing trend, while the mitochondrial proteins showed an increasing trend (Figure S16). A similar decreasing trend was observed for a group of 28 functionally related rat translation initiation factors. The group of the mRNA splicing proteins was filtered in the Reactome Pathways protein data column of the Protein Discoverer (PDv.2.5) protein report using the filter “*mRNA Splicing*”, whereas the “*Translation factors*” filter in the WikiPathways column of the report yielded the translation factors proteins. This trend is understandable because such housekeeping protein production in cells initiates early in the postnatal development, and the decreasing abundance of ribosomal and mRNA regulatory proteins during progressing development corroborates it. The mouse synaptosome study1 did not produce any statistically significant mRNA splicing protein changes, identifying only eight proteins in this category, which were in common with this current rat dataset. This stands in contrast to the 56 rat proteins quantified in the current study, thus indicating that this protein group was likely underrepresented and residual in the mouse synaptosome fraction. There were no mRNA splicing proteins and only one translation factor, elongation factor 2, quantified, which was in common between the current rat data and the previous rat synaptosome cortex dataset in Supplementary Table 5 data reported in ref 5. This finding demonstrated again the presence of specific differences in the datasets, originating likely from the different sample preparation methodologies (e.g., using synaptic isolates vs whole tissue digests).

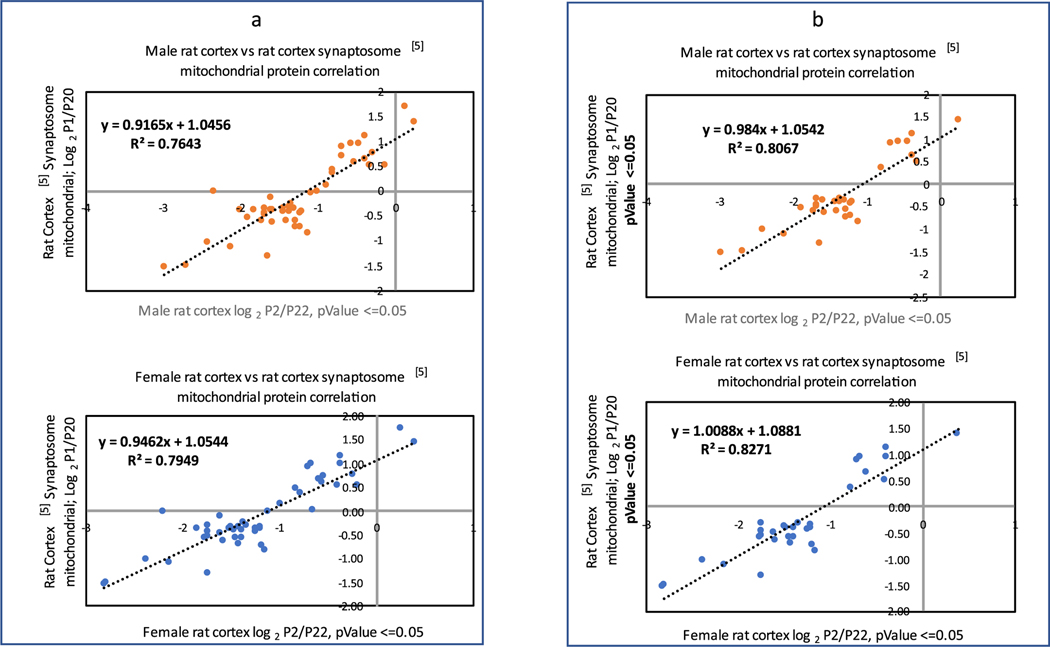

There were 200 mitochondrial proteins identified in the current male and female rat rostral cortex work, which were matched by gene symbols and assembled with their quantitative abundance ratio values. The mitochondrial proteins were collected using the keyword “*mitochondrial*” in the description names. Out of these proteins, 161 proteins possessed statistically significant protein abundance PND ratios, whereby at least one PND ratio per protein was characterized by the adjusted p-value of 0.05 or less. The rat cortex study5 provided a list of 128 mitochondrial proteins and their statistically significant quantitative abundance values in Supplementary Table 8 in ref 5. Those were the mitochondrial proteins isolated using sucrose gradient fractionation, in which at least one PND comparison had a statistically significant abundance ratio p-value of 0.05 or lower. Seventy-nine of these proteins5 had gene symbols assigned to them, out of which 47 quantifiable proteins were in common between both rat cortex studies. The matching proteins were identified by the gene symbol (Table S4). For these 47 proteins, log2 (Px average/P20 average) values were calculated from the P1 average, P10 average, and P20 average values provided in Supplementary Table 8 in ref 5, where x is 1 and 10. These calculated relative abundance ratios were compared using PCC with the corresponding log2 (Pn/P22) protein ratios in the current rat cortex work (n-sizes of 2, 8, and 15). The Pearson function values of 0.87 (male rat) and 0.89 (female rat) showed strong correlation and linearity for the P2/P22 vs P1/P205 data (Figure 10a,b).

Figure 10.

(a, b) Linear correlation plots comparing the male (top) and female (bottom) rat rostral cortex logarithmic mitochondrial protein abundance PND ratios P2/P22, passing the adjusted p-value 0.05 threshold, vs the corresponding quantifiable rat cortex synaptosome data.5 The data comprise the mitochondrial proteins identified both in the current work and in the mitochondrial rat fraction study.5 (a) Current rat data possessing the adjusted p-value of 0.05 or lower. (b) Current rat data possessing the adjusted p-value of 0.05 or lower vs the corresponding P1/P20 rat mitochondrial protein abundance logarithmic ratios, calculated only when both the P1 and P20 abundances possessed the p-value of 0.05 or less (as described in ref 5).

The PCC values showed weaker correlations for the comparisons of P8/P22 vs P10/P205 (0.74 male and 0.66 female) and for P15/P22 vs P10/P205 (0.76 male and 0.64 female). The weaker correlation coefficients might be explained by two factors: a prevalence of the closer to parity protein abundance ratios of smaller magnitude for the shorter PND spans and a larger discrepancy between the PND days used in the rat vs rat-synaptosome data comparison. To further explore the best correlation in the P2/P22 vs P1/P20 data subset,5 the group of 47 proteins was reduced to 31 proteins, which possessed the adjusted p-values of 0.05 or lower both for the P2/P22 ratio (in the current study) and P1 and P20 abundances in Supplementary Table 8 in ref 5. The application of this stricter pvalue criterion for the P1 and P20 abundances5 resulted in a slight improvement of the PCC values for the P2/P22 vs P1/ P205 comparison to give 0.90 (male) and 0.91 (female). This modest correlation improvement corresponded to the better linear equation parameters, y = 0.984x + 1.0542, R2 = 0.8067 (male), and y = 1.0088x + 1.0881, R2 = 0.8271 (female), improved from y = 0.9165x + 1.0456, R2 = 0.7643 (male), and y = 0.9462x + 1.0544, R2 = 0.7949 (female), respectively (Figure 10a,b). It is worth noting that these correlation lines exhibited the slope of approximately 1.0 and the intercept of 1.0. The line upward shift by the intercept of 1.0 relative to the hypothetical ideal data match might possibly be explained by the difference in the sample preparation: the current rat cortex mitochondrial proteome came from the unfractionated tissue, while the reference rat cortex data5 originated from the sucrose-gradient fractionated one. In comparison, the same subset of 31 mitochondrial proteins showed the PCC of 0.99 and the linear equation y = 0.9789x − 0.029, R2 = 0.9822, for the comparison of the male rat cortex vs female rat cortex (current study). The line exhibited the slope of 1.0 and the 0.0 intercept, which was consistent with the fact that both male and female samples were prepared in the same laboratory using the same sample preparation protocol and that the male and female proteomes demonstrated overall negligible differences in their cortex PND protein profiles (Table S4).

The comparison of the 27 mouse mitochondrial proteins characterized by the PND BETR trendline parameter equal or lower than 0.0011 and shared with the current rat mitochondrial data demonstrated the PCC values of 0.82 (mouse vs male rat) and 0.77 (mouse vs female rat) for the mouse P9/P211 and rat P8/P22 logarithmic ratios, respectively. The corresponding linear correlation equations demonstrated the following linearity parameters: 0.6111x + 0.4634, R2 = 0.6687 (male), and y = 0.5883x + 0.4217, R2 = 0.5973 (female), which were inferior compared to the ones shown above for the mitochondrial rat vs rat mitochondrial sucrose gradient fraction data correlation.5 The discrepancy between these two data comparisons might have occurred because the mouse mitochondrial proteins were apparently a narrow subset of the synaptosomal sucrose gradient protein fraction,1 whereas specifically, a mitochondrial cortical fraction was used in the rat study.5

DNA- or RNA-related and apoptosis-related proteins were grouped using the appropriate keyword filter in the data report columns (*DNA*, *RNA*, and *apopto*). Ninety-two rat DNA- or RNA-associated proteins mostly decreased between P2 and P22 (Figure S17), which is consistent with the clearly decreasing trend of the previously discussed mRNA and ribosomal proteins belonging to a cell protein infrastructure category. Twenty-six apoptosis-related rat proteins were grouped and graphed (Figure S17); however, they were not characterized by a clear up or down trend, which could be attributed to a complex role of different proteins in the apoptotic neuronal network–brain cortex shaping processes occurring in the early rat PND period;6 this finding was in agreement with the finding that apoptotic cell death in the rat cortex reached the highest level at PND 1.6 Notably, there were no statistically significant PND changes reported for these proteins in the synaptosome (mouse)1 and the synaptosome and mitochondrial (rat)5 fractions.

Male-to-Female Rat Protein Ratios across the PND Timeline

Overall, in this rat proteomic study, 42% of the changing cortex male and female proteins were increasing, and 41% displayed a consistently decreasing trend from P2 through P8 and P15 to the P22 reference point (Figure S18). The average protein ratio increasing trends appeared to be slightly steeper than the average decreasing trends (Figure S18). In general, the largest protein ratio changes were observed for the earliest PND day studied, e.g., the P2/P22 vs P8/P22 and P15/P22, which was in agreement with the finding that the biggest rat brain protein changes occur early in the PND timeline.5 There were no clear, consistent rat male vs female ratio changes identified within the four investigated PND time points P2, P8, P15, and P22, which would demonstrate any development trend differences in the cortex between the male and female rats. The correlation of the log(2)[Px/P22] (x = 2, 8, and 15) protein ratios of the male and female rat data, which possessed the p-values of 0.05 or lower, showed Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) values of 0.99 for x = 2, 0.99 for x = 8, and 0.98 for x = 15 (based on 1670, 1391, and 637 proteins passing this p-value requirement, respectively; pertaining to the data in Table S4). Considering only the statistically significant ratios for the PND 2, 8, and 15 for the presynaptic, postsynaptic, and adhesion protein data subset, the corresponding PCC values were 0.99, 0.99, and 0.99, respectively. In the latter male and female rat protein subset, 81% of log(2)[P2/P22] values were below zero, thus indicating an increasing trend between P2 and P22, and 19% showed a decreasing trend between these two time points.

Comparison of the 2D-PAGE Rat Cortex PND Data with the Current Rat Study Data

Cerebral cortex samples obtained from the rat PND points P7, P90, and P637 were analyzed by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2DE) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS).4 Seventy-three proteins, which were described in the 2D-PAGE study in Table 1 in ref 4 as either up- or down-regulated between P7 and P90, were also identified in the current rat work. Despite the significant difference in time between the reference points P22 and P90,4 85% of the reported proteins agreed in the + or − expression direction sign represented by the log2 (P8/P22) ratio (current work) and the P7/P90 up- or down-regulation direction. The proteins that differed in the reported regulation direction were as follows: ACAT2, PRDX2, GDA, CFL1, GDI2, TMOD2, CALR, HSPA8, TRAP1, ACTB, and TUBA1C. Coincidentally, among these proteins, in the current work, PRDX2, CFL1, GDI2, TMOD2, CALR, HSPA8, TRAP1, ACTB2, and TUBA1C exhibited relatively small P8/P22 protein changes and flat-shaped protein ratio change trends from P2 to P22. This factor could explain the expression-direction discrepancy, especially taking into consideration the significant time difference between the closest comparable P22 and the P90 reference points.

CONCLUSIONS

This work demonstrated a cross-study PND proteomic data comparison between the current rat cortex work (P2, P8, P15, and P22) and the three other past studies: the mouse cortex synaptosomal fraction (P9, P15, and P21),1 the rat cortex synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions (P1, P10, and P20),5 and the rat cortex proteomic study involving 2D-PAGE gel analysis (P7 and P90).4 The synaptic and mitochondrial protein PND ratios obtained from the current rat cortex work correlated well with the similar PND ratios obtained from the rat cortex synaptosomal and mitochondrial cellular fractions.5 An excellent correlation was found in this work between the male and female rat cortex proteomes during the early PND, P2–P22. In addition, 85% of the quantified proteins that were found in common between this study and the 2D-PAGE gel analysis4 agreed in direction of the protein up- or down-regulation at the PND time points. The current dataset represented an unfractionated rat rostral cortex proteome, and therefore, it provided complementary data to the data obtained using cellular fractionation in combination with other analytical techniques. Linear regression–correlation and PCC tools were particularly useful in identifying, on a global scale, differences between the PND proteomic profiles within the protein groups. This study showed that the early PND rat cortex and the mouse synaptic protein profiles were similar despite comparing the unfractionated rat rostral cortex proteome to the mouse cortex fractionated synaptosome. However, other synaptosome protein groups, which were reported as differentially quantified in both studies, displayed generally flatter mouse vs rat cortex PND protein ratio profiles and worse correlation coefficients, which possibly might be explained by the lower abundance of such proteins in the mouse synaptosomal fraction.1 Hence, as a recommendation and a future project direction, to make datasets fully comparable in future mouse-to-rat comparative proteomic work, it is advisable that the same sample preparation protocols and PND time points be used in both studies. Such an approach could then make a standardized interspecies protein developmental profile fully comparable for the whole set of proteins. The early PND profiles demonstrated that the rat profiles P2– P22 (current work) were consistent with those constructed from the rat synaptosome data presented in ref 5. Overall, the current study demonstrated that the high-resolution LC–MS LFQ method in conjunction with the facile, TFA-based, and detergent-free brain protein extraction technique can be confidently used for PND brain protein profiling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Yue Ge and Colette Miller for performing an EPA internal review for this manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the excellent services provided by Tracey Beasley, Garyn Jung, Kathy McDaniels, and the animal care staff.

The research described in this article has been reviewed by the Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00172.

Figures S1–S13: additional PND protein ratio trendline comparisons between this work protein ratio data and the corresponding data obtained from refs 1 and 5; Figures S14–S18: box and whisker plots showing the log2 Pn/P22/P22 (male and female rat rostral cortices) and log2 Px/P21 (mouse cortex1) protein abundance ratio data point distributions for the PND points (n = 2, 8, 15, and 22 (rat) and x = 9, 15, and 21 (mouse) for the proteins described in the caption within the file); Figure S19: PCA grouping of the rat PND 2, 8, 15, and 22 male and female groups (six animals per group) (PDF)

Table S1: complete protein result data report that was exported from PDv2.5 to Microsoft Excel, showing the protein identification and quantification results for the rat rostral cortex samples at PND 2, 8, 15, and 22 (XLSX)

Table S2: protein processing protocol exported from PDv2.5, describing the PDv2.5 settings for the first stage of sample analysis focusing on protein identification (PDF)

Table S3: protein consensus protocol exported from PDv2.5, describing the PDv2.5 settings for the second stage of sample analysis focusing on protein quantification (LFQ) (PDF)

Table S4: developed based on the data from Table S1, showing the side-by-side comparison of the rat rostral cortex data and the corresponding data obtained from refs 1, 5, and 8 (XLSX)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00172

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Witold M. Winnik, Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27711, United States

William Padgett, Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27711, United States.

Emily M. Pitzer, Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27711, United States

David W. Herr, Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27711, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Gonzalez-Lozano MA; Klemmer P; Gebuis T; Hassan C; van Nierop P; van Kesteren RE; Smit AB; Li KW Dynamics of the mouse brain cortical synaptic proteome during postnatal brain development. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 35456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Breen MS; Ozcan S; Ramsey JM; Wang Z; Ma’ayan A; Rustogi N; Gottschalk MG; Webster MJ; Weickert CS; Buxbaum JD; Bahn S. Temporal proteomic profiling of postnatal human cortical development. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McClatchy DB; Liao L; Park SK; Venable JD; Yates JR Quantification of the synaptosomal proteome of the rat cerebellum during post-natal development. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1378–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wille M; Schumann A; Kreutzer M; Glocker MO; Wree A; Mutzbauer G; Schmitt O. Differential Proteomics of the Cerebral Cortex of Juvenile, Adult and Aged Rats: An Ontogenetic Study. J. Proteomics Bioinform 2017, 10, 41. [Google Scholar]

- (5).McClatchy DB; Liao L; Lee JH; Park SK; Yates JR III Dynamics of Subcellular Proteomes During Brain Development. J. Proteome Res 2012, 11, 2467–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Drastichova Z; Rudajev V; Pallag G; Novotny J. Proteome profiling of different rat brain regions reveals the modulatory effect of prolonged maternal separation on proteins involved in cell death-related processes. Biol. Res 2021, 54, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Doellinger J; Schneider A; Hoeller M; Lasch P. Sample Preparation by Easy Extraction and Digestion (SPEED) - A Universal, Rapid, and Detergent-free Protocol for Proteomics Based on Acid Extraction. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2020, 19, 209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sorokina O; Mclean C; Croning MDR; Heil KF; Wysocka E; He X; Sterratt D; Grant SGN; Simpson TI; Armstrong JD A unified resource and configurable model of the synapse proteome and its role in disease. Sci. Rep 2021, 11, 9967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]