Abstract

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are common in nursing home residents, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now require that nonpharmacological interventions be used as a first-line treatment. Few staff know how to implement these interventions. The purpose of this study was to pilot test an implementation strategy, Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (EIT-4-BPSD), which was developed to help staff integrate behavioral interventions into routine care. The EIT-4-BPSD was implemented in 2 nursing homes, and 21 residents were recruited. A research nurse facilitator worked with facility champions and a stakeholder team to implement the 4 steps of EIT-4-BPSD. There was evidence of reach to all staff; effectiveness with improvement in residents’ quality of life and a decrease in agitation; adoption based on the environment, policy, and care plan changes; and implementation and plans for maintenance beyond the 6-month intervention period.

Keywords: behavioral symptoms, implementation research, nursing homes, psychotropics

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), which include aggression, agitation, depression, anxiety, apathy and hallucinations, are exhibited by up to 90% of nursing facility residents. 1 Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia result in negative health outcomes 2,3 and put residents at risk of inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs, physical activity limitations, and other restraining methods that reduce function, 4 increase social isolation, 3 and increase the risk of physical abuse. 5 Prior work has shown that behavioral approaches can reduce BPSD in nursing home residents 6 -13 and should be considered as the first-line treatment for BPSD in this population. 12,14

Nonpharmacologic Approaches for the Management of BPSD

Nonpharmacologic or behavioral approaches for the management of BPSD include sensory, psychological, functional, and behavioral interventions. 6,13,15 -19 Training and supervising long-term care staff to consider resident preferences and using person-centered communication skills, relationship-oriented behavioral strategies (such as consistent assignment), good communication skills, and teamwork facilitate implementation of these approaches and decrease BPSD among residents. 13 Focusing on the individual as a person and using strategies to optimize function, such as those used in function focused care approaches, 7,8,20 -25 are likewise central to the prevention and management of “rejection of care” forms of BPSD, which occur with high frequency in these environments. 26 Function-focused care approaches are those that help residents optimize function and physical activity during all care interventions and include things such as facilitating self-feeding or making the resident to wash his or her own face and teeth by modeling that behavior. Function-focused care approaches can not only prevent behaviors such as resistance to care or rejection of care (eg, turning away, pushing, or hitting) but can also optimize the resident’s function and increase time spent in physical activity, both of which are important for overall health and quality of life. 7,8,20 -25

Approaches that utilize recreational activities and are tailored to resident preferences/interests and remaining abilities have also been shown to be effective in not only reducing the frequency and intensity of BPSD but also in increasing the occurrence of positive behavior and emotional states. 9,11 Many other examples of evidence-based behavioral interventions have been demonstrated in the literature leading to the creation of a “library” of these approaches in a website that is freely accessible to providers and researchers (www.nursinghometoolkit.com).

Challenges to Implementation of Nonpharmacologic Approaches for BPSD

Despite regulatory requirements and availability of educational materials focused on the nonpharmacological management of BPSD, less than 2% of nursing homes consistently implement behavioral approaches. 14 Established barriers to the use of behavioral approaches and integration of these approaches as routine care within facilities include lack of knowledge, skills, and hands-on experience among staff with the many different types of effective nonpharmacological approaches, beliefs in the superiority of psychotropic medications over behavioral interventions, willingness to defer management of BPSD to psychiatric consultants, lack of staff motivation to use nonpharmacologic strategies consistently, lack of belief in the utility and feasibility of nonpharmacologic approaches, insufficient support from administration, inadequate staffing levels, competing workload concerns, staff turnover, and lack of fit between the intervention and the philosophy of care within the setting. 27 -33 Moreover, even when staff want to use behavioral approaches for the management of BPSD for their residents, they lack the skills to plan and actually implement a practice change. 30,34

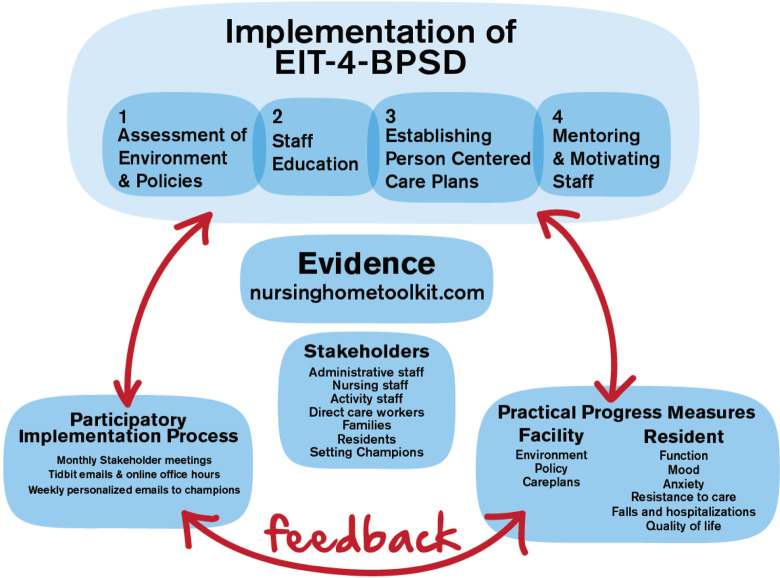

Our implementation approach, Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (EIT-4-BPSD), is designed to overcome barriers to the use of behavioral approaches for BPSD by offering a theory-based, systematic, comprehensive implementation strategy. Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia includes a 4-step approach—step 1: assessment of the environment and policies; step 2: staff education; step 3: establishment of person-centered care plans; and step 4: mentoring and motivating of staff. The goal is to teach and motivate staff in long-term care settings to evaluate residents with regard to their personal preferences, use appropriate communication techniques, facilitate participation in care-related activities and physical activity, and develop a plan of care that incorporates personal preferences and best prevents and manages BPSD. The educational resources are available in the Nursing Home Toolkit (www.nursinghometoolkit.com), 35 an online repository of resources that our team developed in partnership with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). The Nursing Home Toolkit includes 5 sections: introduction to the philosophy of person-centered care; system integration processes; education and leadership programs in response to BPSD; tools for the assessment of BPSD; and pragmatic behavioral approaches for BPSD.

Theoretical Approach Guiding the EIT-4-BPSD

The evidence integration triangle (EIT) 36,37 is a parsimonious, participatory framework that has been shown to facilitate implementation of interventions in primary care and oncology centers. 37,38 The pragmatic EIT process begins and ends with the engagement of local stakeholders. Setting specific challenges and barriers is identified, and the intervention is adjusted to meet the needs of the setting. The use of EIT integrates evidence using practical approaches and measures and assures continual feedback from stakeholders. The context is also considered within EIT including the environment within the setting, the policies, the cultural context, and interpersonal relationships and intrapersonal factors among staff.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the 3-pronged framework of EIT-4-BPSD. Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia is implemented by a research nurse facilitator who identifies and works with a champion(s) in the settings to implement the 4 steps of EIT-4-BPSD (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Implementation of Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (EIT-4-BPSD).

Table 1.

Four Steps of EIT-4-BPSD.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Assessment of the environment and policies | Using established assessment forms, the champion and research nurse facilitator assess the environment and policies for evidence of resources and support to implement nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent and manage BPSD. |

| Recommendations for changes are then discussed with administration. | |

| Step 2: Staff education | Using a developed educational PowerPoint of the champion and research nurse facilitator coordinate and plan educational sessions for the staff in a way that meets the needs of the facility (eg, multiple face-to-face sessions; online training). |

| Step 3: Establishment of person-centered care plans | Using assessment resources such as the Describe, Investigate, Create and Evaluate tool and the Physical Capability Assessment, and the Resident Assessment of Preferences, the Research Nurse Facilitator works with the champion and other staff to develop person-centered care plans to prevent and decrease BPSD while optimizing function and physical activity. |

| Step 4: Mentoring and motivating of staff | Self-efficacy-based approaches (performance, verbal encouragement, role modeling and elimination of unpleasant sensations) are used for mentoring and motivating the staff on the use of behavioral approaches for prevention and management of BPSD. |

| The champion works individually with direct-care workers to evaluate resident–staff interaction and assure that the direct care workers are using appropriate behavioral interventions. Contests are implemented to reward, support, and encourage the use of behavioral approaches for BPSD among staff. |

Abbreviations: BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; EIT-4-BPSD, Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia.

The purpose of this study was to pilot test the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the EIT-4-BPSD using components of the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) model. 39 The following hypotheses were used to evaluate preliminary effectiveness: (1) Residents exposed to EIT-4-BPSD will experience less BPSD, maintain or improve function, have reduced the use of psychotropic medications, and improved the quality of life over the course of the 6-month study period; and (2) Facilities exposed to EIT-4-BPSD will demonstrate improvements in environment and policy assessments that reflect support for behavioral approaches for BPSD and increase the use of behavioral approaches to manage behavioral symptoms in the residents’ care plans.

Methods

Design and Setting

This was a single-group repeated-measures study comparing findings pre and postimplementation of EIT-4-BPSD. The study was done in 2 nursing home settings, 1 in Maryland and 1 in Pennsylvania. One setting was a 46-bed skilled nursing facility housed within a continuing care retirement community and the other was a single 45-bed unit in a 175-bed-skilled nursing facility. Prior to study implementation, meetings were held in each setting with a team that included a primary contact individual (in 1 site, it was an advanced practice nurse and in the other it was a social worker) and other interested staff to review the study intervention and identify a champion and stakeholder team members. In 1 site, the stakeholder team included the research staff (the research nurse facilitator and a research investigator), the facility champion (a direct care worker), the director of nursing, the nursing home administrator, an activity staff member, a unit charge nurse, and an advanced practice nurse. In the other site, the team included the research staff, the facility champion (a social worker), the director of nursing, licensed nursing staff, activity staff, direct care workers, a family member, and a resident.

Resident Sample

Residents were eligible to participate if they (1) were living in a participating nursing home; (2) were 55 years or older; (3) had a history within the past month of exhibiting at least 1 BPSD; (4) had cognitive impairment as determined by a score of 0 to 12 on the Brief Interview of Mental Status (BIMS) 40 ; (5) were not enrolled in Hospice; and (6) were not in the nursing facility for short-stay rehabilitation care. A list of all eligible residents was obtained from a designated staff member, and residents were then randomly approached with the goal of recruiting 10 to 15 residents per setting. Potentially eligible residents were approached to discuss the study and complete the Evaluation to Sign Consent (ESC). 41 Evidence of ability to sign consent was based on correct responses to all 5 items on the ESC. If decisional capacity to consent to participate was impaired, then assent was obtained from the resident, and the legally authorized representative (LAR) was approached to complete the consent process. A total of 37 residents were approached, and 21 (57%) were consented. The major reasons for inability to consent were due to the lack of assent from the resident (eg, no response during interactions or refusal) and inability to reach the LAR.

Measures

Table 2 provides an overview of all measures for each component of RE-AIM. All measures used with residents have established reliability and validity when used with older adults. Cognitive status was measured using the BIMS, which includes a 3-item recall and orientation questions with scores ranging from 0 to 15. 40 Health status was evaluated using the cumulative Illness Rating Scale which rates both illness severity and comorbidity and includes 13 systems and a psychiatric/behavioral rating. 43,44 Resident behavioral symptoms included assessment of depressive symptoms using the 19-item Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. 46 Aggressive and/or resistive behaviors during care activities were measured using the 13-item Resistiveness to Care Scale. 47 Pain was evaluated using the Pain-AD measure, which is an observational tool to assess pain in older adults who have dementia or other cognitive impairment and are unable to reliably communicate their pain. 42 Agitated behaviors were evaluated using the 14-item Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI). 48 Performance of basic functional tasks was evaluated using the 10-item Barthel Index (BI). 49 The 13-item Quality of Life–AD scale was used to consider the resident’s quality of life. Measures were completed based on the input from the direct care worker providing care to the resident on the day of testing. Adverse events included the number of falls and transfers to the hospital or emergency department.

Table 2.

Outcome Measures for Each Component of RE-AIM.

| Construct | Focus of Measure | Source | Time | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptives/covariates | ||||

| Demographics | Resident | Medical record | Baseline | Age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, length of stay |

| Pain | Resident | Research evaluator | Baseline, 6 months | Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale 42 |

| Cognitive status | Resident | Medical record | Baseline, 6 months | Brief Interview of Mental Status 40 |

| Health status | Resident | Medical record | Baseline, 6 months | Cumulative Illness Rating Scale total score 43,44 ; number of medications prescribed |

| Reach | ||||

| Participation | Facility | Research team; research nurse facilitator | Baseline | Number of staff that are exposed to educational material |

| Effectiveness | ||||

| Environmental modification | Facility (all) | Research evaluator | Baseline, 6 months | Environment assessment total score 45 |

| Policy modification | Facility (all) | Research evaluator | Baseline, 6 months | Policy assessment total score 45 |

| BPSD: depression | Resident | Staff informant | Baseline, 6 months | Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia 46 |

| BPSD: resistance to care | Resident | Staff informant | Baseline, 6 months | Resistiveness to Care Scale 47 |

| BPSD: agitation | Resident | Staff informant | Baseline, 6 months | Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory 48 |

| Function | Resident | Staff informant | Baseline, 6 months | Barthel index 49 |

| Quality of life | Resident | Staff informant | Baseline, 6 months | Quality of Life-AD |

| Adoption | ||||

| Participation in initial and monthly stakeholder team training | Facility (EIT-4-BPSD only) | Research nurse facilitator | Baseline-6 months | Number of monthly meetings attended by the stakeholder team |

| Environment and policy change | Facility | Research evaluator | Baseline, 6 months | Number of observed changes in environment and policy assessments |

| Person-centered care plans for BPSD | Facility | Research evaluator | Baseline, 6 months | Increased evidence of person-centered approaches to BPSD in care plans |

| Implementation/fidelity | ||||

| Delivery of first EIT meeting with team | Facility | Research nurse facilitator | First month | Evidence of completing the initial training meeting |

| Delivery of 4 steps of EIT-4-BPSD—step 1: environment/policy assessments; step 2: education of staff; step 3: development of care plans for BPSD; step 4: mentoring and motivating. | Facility | Research nurse facilitator | During 6-month period | Step 1: completion of environment and policy assessments; step 2: percentage of staff participating in educational sessions; step 3: development of care plans with person-centered interventions for BPSD based on checklist; step 4: evidence from the internal champion of use of huddles; participation in contests; provision of verbal encouragement of staff; completion of the observations using the behavioral interventions for BPSD measure at 0 to 2 and 4 to 6 months of postimplementation of EIT-4-BPSD |

| Receipt of education: step 2 in EIT-4-BPSD | Facility | Internal champion | 0 to 2 months | Evidence of receipt will be based on the percentage of staff obtaining 80% or better total score on knowledge of behavioral interventions for BPSD |

Abbreviations: BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; EIT-4-BPSD, Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia; RE-AIM, Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

Facility and Staff RE-AIM Measures

The Environment Assessment (effectiveness, adoption, maintenance) includes 24 items that impact care of residents with BPSD (eg, availability of outdoor spaces). 45 Similarly, the policy assessment 45 includes 24 items that reflect policies that support behavioral approaches for BPSD (eg, policies on the use of restraints and evaluation of resident preferences). For both measures, items are scored as present or not present and summed. Appropriate development of care plans was evaluated using the care plan checklist for evidence of person-centered approaches for BPSD. This measure focuses on evidence within the care plan of use of behavioral approaches to prevent or manage BPSD (apathy, agitation, inappropriate/disruptive vocalizations, aggression, wandering, repetitive behaviors, resistance to care, and sexually inappropriate behaviors). Evidence was based on care plans noting, for example, that managing resistance to bathing was done by establishing a person-centered plan for bathing and functionally engaging the resident in his or her own personal care. The Knowledge of Behavioral Interventions for the BPSD test, a 10-item multiple choice test, was used to evaluate staff knowledge in this area.

Procedure

Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia was implemented by the research nurse facilitator working with the internal champion and stakeholders using the 4-step approach (Table 1). Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia involved a combined face-to-face and an Internet-enhanced approach that included ongoing, iterative, and active participation of all stakeholders. The research nurse facilitator arranged the first face-to-face meeting with the internal champion and stakeholders in each facility. This meeting introduced the team to the participatory process and their responsibilities and provided training on the knowledge and skills they needed for implementation. Following this initial face-to-face training, the research nurse facilitator continued to visit the facility monthly for 6 months and worked with the team to implement EIT-4-BPSD. In addition, each week a short “tidbit” was sent out via e-mail to all members of both stakeholder groups. The tidbits focused on innovative ways to engage staff in providing behavioral approaches for BPSD. Examples of tidbits included such things as providing ways for the champions to reinforce and support the staff as they provided appropriate behavioral interventions (eg, giving positive reinforcement and rewards; having contests that reward innovative approaches to preventing resistance to care during bathing) or providing examples of how music was used to decrease agitation with a resident.

Data Analyses

Descriptive analyses were done to describe the sample and the facility (eg, environment and policy assessments) at baseline and follow-up. To consider resident outcomes, generalized estimating equations were used to perform repeated-measures analyses with outcome measures as the dependent variable. An intention-to-treat paradigm was used. All analyses controlled for age and gender. For each outcome, exploratory analyses (scatterplots, frequencies, and boxplots) were performed to assess model assumptions. A P ≤ .05 level of significance was used for all analyses.

Results

As shown in Table 3, the average age of the residents was 85.47 (standard deviation [SD] = 6.04) and the majority of the participants were female (n = 19, 90%), white (n = 18, 86%), and not Hispanic (n = 20, 95%). Only 2 (10%) were married, and the remaining were single, divorced, or widowed. All participants had at least a high school education, with the majority having an undergraduate or graduate college degree. At baseline, residents were significantly impaired cognitively with a score of 3.93 on the BIMs (SD = 4.00); they had 5.61 comorbidities (SD = 2.36), some evidence of pain based on observed symptoms (PAIN-AD mean = 1.82, standard error [SE] = 1.55), some evidence of agitation based on the CMAI (mean = 30.47, SE = 1.59), some resistive behaviors (mean = 3.66, SD = 1.09), fair quality of life (mean = 24.30, SE = 1.22), evidence of depressive symptoms (mean = 10.95, SE = 1.43), and were functionally dependent based on the BI (mean = 39.90, SE = 6.10). Overall, they were on 12.33 medications (SD = 4.47). Eight (38%) received no antipsychotic medications, and the remaining 13 (62%) individuals received anywhere from 1 to 6 dosages per day of antipsychotics. Only 3 (15%) received an anxiolytic and 13 (62%) received an antidepressant. None of the participants were given sedative/hypnotics.

Table 3.

Description of the Sample.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 2 (10) |

| Female | 19 (90) |

| Race | |

| White | 18 (86) |

| Black | 3 (14) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1 (5) |

| Non-Hispanic | 20 (95) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 5 (23) |

| Married | 2 (10) |

| Widowed | 9 (45) |

| Divorced | 3 (15) |

| Missing | 1 (5) |

| Education | |

| High school | 2 (10) |

| College | 11 (52) |

| Graduate education | 3 (14) |

| Unknown | 5 (24) |

| Antipsychotic medications | |

| No | 8 (38) |

| Yes | 13 (62) |

| Antianxiolytics | |

| No | 18 (86) |

| Yes | 3 (14) |

| Antidepressants | |

| No | 8 (38) |

| Yes | 13 (62) |

| Sedatives | |

| No | 21 (100) |

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance Outcomes

Reach

At both settings, we were able to educate all of the direct care staff either during face-to-face education in a group or via follow-up one-on-one education. The stakeholder team members were instrumental in helping to facilitate the educational sessions and assure staff attendance.

Effectiveness

Resident outcomes

Follow-up was conducted on 18 (86%) individuals, and the remaining 3 (14%) individuals died due to an acute medical event during the intervention period. As shown in Table 4 , there was a significant decrease in agitation (Wald χ 2 = 14.60, P = .001) and improvement in quality of life (Wald χ2 = 12.56, P = .001) and a nonsignificant trend toward a decrease in depressive symptoms from baseline to follow-up (Wald χ2 = 3.46, P = .060) and resistance to care (Wald χ2 = 2.70, P = .10). There were no significant changes in pain (Wald χ2 = 1.07, P = .30) or function (Wald χ2 = 0.785, P = .17).

Table 4.

Outcomes Pre- and Postimplementation of EIT-4-BPSD.

| Outcomes/Resident | Range | Baseline | Follow-Up | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Wald χ2 (P) | ||

| Pain | 0.00-5.00 | 1.82 | 1.55 | 1.23 | 1.82 | 1.07 (.30) |

| Agitation | 19.00-47.00 | 30.47 | 1.59 | 21.94 | 1.30 | 14.60 (.001) |

| Function | 3.00-90.00 | 39.90 | 6.10 | 35.72 | 7.28 | 0.785 (.38) |

| Resistive behavior | 0.00-19.00 | 3.66 | 1.09 | 1.50 | 0.64 | 2.70 (.10) |

| Quality of life | 12.00-36.00 | 24.30 | 1.22 | 29.00 | 1.18 | 12.56 (.001) |

| Depressive symptoms | 3.00-23.00 | 10.95 | 1.43 | 7.94 | 1.46 | 3.46 (.06) |

| Antidepressants (% receiving treatment) | 0%-100% | 62% | 0.11 | 66% | 0.11 | 0.005 (.94) |

| Anxiolytics (%receiving treatment) | 0%-100% | 14% | 0.07 | 16% | 0.09 | 1.78 (.18) |

| Antipsychotics (% receiving treatment) | 0%-100% | 62% | 0.11 | 66% | 0.11 | 0.15 (.75) |

| Care plans (number of behaviors with person-centered behavioral approaches) | 0-8 | 4.24 | 0.50 | 4.72 | 0.48 | 5.52 (.02) |

Abbreviations: BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; EIT-4-BPSD, Evidence Integration Triangle for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia; SE, standard error.

There were no significant changes in the use of any psychotropic medications during the course of the study period. Sixty-two percent (SE = 0.11) of the participants were on an antidepressant at baseline and 61% (SE = 0.11) at follow-up (P = .94), 14% (SE = 0.07) were on anxiolytics at baseline and 16% (SE = 0.09) at follow-up (P = .18), and 62% (SE = 0.11) were on antipsychotics at baseline and this increased to 66% (SE = 0.11) at follow-up (P = .74). None of the participants were on sedative hypnotics at either baseline or follow-up.

Facility outcomes

At baseline, there was a mean of 20.00 (SD = 1.41) out of 24 environmental factors that were present in the settings to facilitate the use of behavioral approaches for the management of BPSD. At follow-up, this increased to a mean of 21.50 (SD = 2.12). Likewise, there was a change in the number of policies within the settings that reflected a person-centered approach to BPSD and use of behavioral interventions. The evaluation of policies at baseline showed a mean of 16.50 (SD = .71) out of 24 policy items evaluated that supported behavioral approaches to BPSD and at follow-up the mean increased to 21.00 (SD = 1.41). Evaluation of care plans at baseline showed that care plans reflected a mean of 4.24 (SE = 0.50) out of a possible 8 behavioral symptoms that had evidence of the management of the symptom using a behavioral approach. At follow-up, there was a significant increase (P = .02) to a mean of 4.72 (SE = 0.48) symptoms that had behavioral interventions incorporated into the care plan.

Adoption

There was evidence of adoption of the EIT-4-BPSD based on active and full participation among the stakeholder teams at each of our monthly meetings. In addition, the stakeholders read and utilized the monthly tidbits and planned for ongoing implementation of the approaches learned (eg, care plan development, increased focus on optimizing function and physical activity to decrease BPSD). As noted above, there was an increase of approximately 2 environmental resources and an increase of 5 policy changes that facilitated opportunities for behavioral approaches for BPSD across both settings. Examples of environmental changes included having age and skill appropriate resources available and used during activities such as physical activity BINGO or an adult coloring mural. Policy changes included encouraging versus discouraging physical activities after a fall. In addition, there was evidence of positive changes in care plans with an increased use of behavioral interventions.

Implementation

All of the stakeholder meetings were completed as intended, and all steps of the EIT-4-BPSD were provided across both settings. As noted, there was some evidence of receipt of information about behavioral approaches for BPSD based on a mean score of 73% (SD = .16) on the Knowledge of Behavioral Interventions for the BPSD test.

Discussion

The findings from this pilot study provide some preliminary support for EIT-4-BPSD, an approach that helps staff change how BPSD is managed within the nursing home. Across both settings, the stakeholder teams were very supportive of the implementation of EIT-4-BPSD and attended the monthly meetings and supported the staff in related activities. Scheduling of the meetings was sometimes challenging, and identification of a set monthly time is strongly recommended so that calendars can be set for each stakeholder team member. Feedback from the stakeholders was also very positive in terms of recognition that the implementation of EIT-4-BPSD was raising awareness across the settings to consider the use of behavioral approaches for BPSD rather than simply requesting medication management to address the behaviors. The stakeholder team members noted, however, that they needed more than 6 months to work with all staff and truly incorporate behavioral approaches into routine care.

In terms of study outcomes, the study participants had significant cognitive impairment, and thus, it was difficult to achieve any measurable improvements based on the measures used in physical function or to evaluate the quality of life. This was despite the fact that the measures used were developed specifically for those with cognitive impairment. Ongoing research is needed to establish how to best evaluate functional changes and psychosocial outcomes among residents with moderate to severe dementia.

With regard to medication management for BPSD, the percentage of study participants receiving antidepressants and antipsychotics was higher in our sample than what is seen in the National Medicare Data. 50,51 There was no significant change by the end of the 6-month study period in the percentage of individuals receiving psychotropic medications. The focus of the intervention was on implementing the use of behavioral interventions with the intention of indirectly decreasing the need for and use of pharmacological agents for the management of BPSD. We did not, however, encourage the nurses to request that providers decrease drug use as behavioral interventions were implemented. In addition, we did not invite individuals prescribing these agents to be members of the stakeholder team. Prior research has demonstrated that a focus on prescribers when implementing interventions to increase the use of behavioral approaches is an effective way to decrease medication use. 52,53 Inclusion of individuals prescribing psychotropic medications on the stakeholder team should be incorporated in future implementation of EIT-4-BPSD.

Although the stakeholders were all very supportive in using behavioral approaches for BPSD, the majority of the stakeholder team was not actively involved with the day-to-day care of residents. Despite their lack of direct care, as has been shown in prior research, 54 having the support of the stakeholders was a critical first step to changing behavior among direct caregivers with regard to the management of BPSD. In addition to the support of the stakeholders, education was an important initial step to changing how care was provided. Education, however, was not sufficient when provided alone without other components of the intervention focused on changing the behavior of staff. 55,56 As noted by the research nurse facilitators, in addition to education, it was critical to spend time during the monthly visit on the unit working with the champion(s) and other staff implementing the skills taught and discussed during the monthly meetings. The monthly meeting time was generally divided so that this could be done.

With regard to the effectiveness of the intervention, there were a number of positive findings reflecting the benefit of EIT-4-BPSD at the setting and resident level. Noted changes at the setting level were based on descriptive results given our inclusion of only 2 settings. These changes included such things as making activity resources available to staff such as physical activity BINGO or an adult coloring mural so they could use these materials to engage residents in some type of activity. It is possible that the opportunities to engage in these activities replaced wandering and other BPSDs that might otherwise have occurred. 57 -59 Future testing needs to include a larger randomized sample of settings to establish the impact of EIT-4-BPSD on organizational changes and the subsequent effect that has on the management of BPSD.

In addition to changes in environments and policies, there was an increase in the number of BPSDs in which there were appropriate interventions recommended in the resident’s care plan. Based on data collected, we do not know whether the care plans were actually implemented as planned. The changes noted in the care plans, however, reflect evidence of adoption of recommended approaches for the behavioral management of BPSD. Objective measures are needed in future work to evaluate staff interaction with residents to determine whether the care plans were implemented as written.

Our findings suggested a small, albeit significant, improvement in BPSD among residents with regard to decreasing agitation and improving quality of life and a trend toward decreasing depressive symptoms and resistive behavior. The intervention activities, specifically the 4-step approach, extends beyond education and uses self-efficacy-based interventions to engage and reinforce staff for use of behavioral approaches for the management of BPSD. Further, the staff was taught to use person-centered approaches to address BPSD with a variety of intervention options as delineated in the nursinghometoolkit.com. A toolkit approach that provides a variety of interventions to manage BPSD has also previously been shown to be more useful 56 than a single intervention implemented with all residents such as simulated presence 60 or passive music therapy. 61

Study Limitations and Conclusion

This study was limited by sample size and the lack of a control group, the lack of objective assessments of staff behavior, and measurement challenges when evaluating residents with moderate to severe dementia (ie, the inability to get subjective input from these individuals). Despite these limitations, the study provides some evidence of the feasibility of EIT-4-BPSD and preliminary efficacy of the approach in terms of decreasing BPSD through the use of behavioral approaches. Revisions of EIT-4-BPSD should include the incorporation of prescribers of psychotropic medications on the stakeholder team, consideration of additional measures that may be more appropriate for residents with moderate to severe dementia with regard to function and quality of life, and inclusion of an observation measure of staff to indicate that care plan approaches are being implemented as intended.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a John A Hartford Foundation Research Facilitation Grant.

References

- 1. Kales H, Gitlin L, Lyketsos C; Detroit Expert Panel on Assessment and Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):762–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galynker II, Roane DM, Miner C, Feinberg T, Watts B. Negative symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psych. 1995;3(1):52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wunderlich G, Kohler P. Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. Web site. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=9611. Accessed January 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, et al. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999-2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dyer C, Pavlik V, Murphy K, Hyman D. The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(2):205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richter T, Meyer G, Möhler R, Köpke S. Psychosocial interventions for reducing antipsychotic medication in care home residents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD008634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galik E, Resnick B, Hammersla M, Brightwater J. Optimizing function and physical activity among nursing home residents with dementia: testing the impact of function focused care. Gerontologist. 2014;54(6):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu F, Kolanowski A, Litaker M. The association of physical function with agitation and passivity in nursing home residents with dementia. J Geron Nurs. 2006;32(12):30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kolanowski A, Litaker M, Buettner L, Moeller J, Costa P. A randomized clinical trial of theory-based activities for the behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(6):1032–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kolanowski A, Buettner L. Prescribing activities that engage passive residents. An innovative method. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(1):13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Haitsma K, Curyto K, Abbott K, Towsley G, Spector A, Kleban MA. Randomized controlled trial for an individualized positive psychosocial intervention for the affective and behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(1):35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper C, Mukadam N, Katona C, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions to improve quality of life and well-being in people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Livingston G, Kelly L, Lewis-Holmes E, et al. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sensory, psychological and behavioural interventions for managing agitation in older adults with dementia. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(39):1–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grabowski D, O’Malley A, Afendulis C, Caudry DJ, Elliot A, Zimmerman S. Culture change and nursing home quality of care. Gerontologist. 2014;54(suppl 1):S35–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li J, Porock D. Resident outcomes of person-centered care in long-term care: a narrative review of interventional research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(10):1395–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Testad I, Corbett A, Aarsland D, et al. The value of personalized psychosocial interventions to address behavioral and psychological symptoms in people with dementia living in care home settings: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(7):1099–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O’Connor D, Ames D, Gardner B, King M. Psychosocial treatments of behavior symptoms in dementia: a systematic review of reports meeting quality standards. Int J Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):225–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen-Mansfield J, Buckwalter K, Beattie E, Rose K, Neville C, Kolanowski A. Expanded review criteria: the case of nonpharmacological interventions in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(1):15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Galik E, Pretzer-Aboff I, Resnick B. Nurses perspective of function focused care in acute care. Int J Older Adults. 2011;15(1):48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galik E, Resnick B, Pretzer-Aboff I. Knowing what makes them tick: motivating cognitively impaired older adults to participate in restorative care. Int J Nurs Pract. 2009;15(1):48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Galik E, Resnick B, Lerner N, Hammersla M, Gruber-Baldini A. Function focused care for assisted living in residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2015;55(suppl 1):S13–S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galik EM, Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini A, Nahm ES, Pearson K, Pretzer-Aboff I. Pilot testing of the restorative care intervention for the cognitively impaired. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(7):516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Resnick B, Galik E, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman S. Testing the impact of function focused care in assisted living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman SI, et al. Nursing home resident outcomes from the res-care intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1156–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ishii S, Steim J, Saliba C. A conceptual framework for rejection of care behaviors: review of literature and analysis of role of dementia severity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(1):11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marx K, Stanley I, Van Haitsma K, et al. Knowing versus doing: education and training needs of staff in a chronic care hospital unit for individuals with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(12):26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolanowski A, Fick D, Frazer C, Penrod J. It’s about time: use of nonpharmacological interventions in the nursing home. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42(2):214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kolanowski A, Van Haitsma K, Penrod J, Hill N, Yevchak A. Wish we would have known that! communication breakdown impedes person-centered care. Gerontologist. 2015;55(suppl 1)S50–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beck C, Heacock P, Mercer S, et al. Sustaining a best-care practice in a nursing home. J Healthc Qual. 2005;27(4):5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parrish M, O’Malley K, Adams R, Adams S, Coleman E. Implementation of the care transitions intervention: sustainability and lessons learned. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14(6):282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lekan-Rutledge D, Palmer MH, Belyea M. In their own words: nursing assistants’ perceptions of barriers to implementation of prompted voiding in long-term care. Gerontologist. 1998;38(3):370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finucane A, Stevenson B, Moyes R, Oxenham D, Murray S. Improving end-of-life care in nursing homes: implementation and evaluation of an intervention to sustain quality of care. Palliat Med. 2013;27(8):772–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anderson R, Toles M, Corazzini K, McDaniel R, Colon-Emeric C. Local interaction strategies and capacity for better care in nursing homes: a multiple case study. BMC Health Services Res. 2014;14:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nursing Home Toolkit. Nursing Home Toolkit. Web site. www.nursinghometoolkit.com. Accessed January 2015.

- 36. Glasgow R, Green L, Taylor M, Stange K. An evidence integration triangle for aligning science with policy and practice. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):646–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lazenby M. The international endorsement of US distress screening and psychosocial guidelines in oncology: a model for dissemination. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(2):221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glasgow R, Kaplan R, Ockene J, Fisher EB, Emmons KM. Patient reported measures of psychosocial health behavior should be added to electronic health records. Health Aff. 2012;31(3):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Virigina Tech. What is RE-AIM. Web site: http://www.re-aim.hnfe.vt.edu/about_re-aim/what_is_re-aim/index.html. Accessed January 2016.

- 40. Brief Interview of Mental Status. Web site: http://dhmh.dfmc.org/longtermcare/documents/bims_form_instructions.pdf. Accessed January 2016.

- 41. Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini AL, Aboff-Petzer I, et al. Reliability and validity of the evaluation to sign consent measure. Gerontologist. 2007;47(1):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Linn B, Linn M, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16(5):622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Parmelee P, Thuras P, Katz I, Lawton M. Validation of the cumulative illness rating scale in a geriatric residential population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(2):130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alexopoulos G, Abrams R, Young R, Shamoian C. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mahoney E, Hurley A, Volicer L, et al. Development and testing of the Resistiveness to Care Scale. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22(1):27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cohen-Mansfield J. Instructional manual for the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. Web site: http://www.dementia-assessment.com.au/symptoms/CMAI_Scale.pdf. Accessed January 2016.

- 48. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14(2):61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Logsdon R, Gibbons L, McCurry S, Teri L. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):510–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dutcher S, Rattinger G, Langenberg P, et al. Effect of medications on physical function and cognition in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1046–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mallot R., Safeguarding NH. Residents & Program Integrity. Web site. http://www.ltccc.org/publications/documents/LTCCC-Report-Safeguarding-Nursing-Home-ResidentsProgram-Integrity-SA-Performance-Review-2015.pdf. Accessed August 2016.

- 52. Vida S, Monette J, Wilchesky M, et al. A long term care center interdisciplinary education program for antipsychotic use in dementia: program update five years later. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(4):599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rapp M, Mell T, Majic T, et al. Agitation in nursing home residents with dementia (VIDEANT trial): effects of a cluster-randomized, controlled, guideline implementation trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(9):690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Koder D, Hunt G, Davison T. Staff’s views on managing symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. Nurs Older People. 2014;26(10):31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jeon Y, Govett J, Low L, et al. Care planning practices for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in residential aged care: a pilot of an education toolkit informed by the aged care funding instrument. Contemp Nurse. 2013;44(2):156–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fitzsimmons S, Barba B, Stump M. Diversional and physical nonpharmacological interventions for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Geron Nurs. 2015;41(2):8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Smith M, Schultz S, Seydel L, et al. Improving antipsychotic agent use in nursing homes. J Geron Nurs. 2013;39(5):24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Denning S. How do you change an organizational culture? Forbes. 2011. Web site. http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/07/23/how-do-you-change-an-organizational-culture/#356516693baa. Accessed August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen Y, Briesacher B, Field T, Tjia J, Lau D, Gurwitz J. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hahn S. Using environment modification and doll therapy in dementia. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;11(1):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Raglio A, Bellandi D, Baiardi P, et al. Effect of active music therapy and individualized listening to music on dementia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(8):1534–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]